Abstract

Treatment of wild type vaccinia virus infected cells with the anti-poxviral drug isatin-β-thiosemicarbazone (IBT) induces the viral postreplicative transcription apparatus to synthesize longer-than-normal mRNAs through an unknown mechanism. Prior studies have shown that virus mutants resistant to or dependent on IBT affect proteins involved in control of viral postreplicative transcription elongation, including G2, J3 and the viral RNA polymerase. Prior studies also suggest that there exist additional unidentified vaccinia genes that influence transcription elongation. The present study was undertaken to target candidate transcription elongation factor genes in an error prone mutagenesis protocol to determine whether IBT resistant or dependent alleles could be isolated in those candidate genes. Mutagenesis of genes in which IBT resistance alleles have previously been isolated, namely A24R (encoding second largest RNA polymerase subunit, rpo132) and G2R (encoding a positive transcription elongation factor), resulted in isolation of novel IBT resistance and dependence alleles therefore providing proof of principle of the targeted mutagenesis technique. The vaccinia H5 protein has been implicated previously in transcription elongation by virtue of its association with the positive elongation factor G2. Mutagenesis of the vaccinia H5R gene resulted in a novel H5R IBT resistance allele, strongly suggesting that H5 is a positive transcription elongation factor.

Keywords: vaccinia virus, genetics, drug resistance, isatin-β-thiosemicarbazone, transcription, RNA polymerase, marker rescue

Introduction

Several vaccinia genes have been identified that control postreplicative vaccinia transcription elongation and/or mRNA 3' end formation (Condit and Niles, 2002). (See companion manuscript for a more detailed summary of vaccinia postreplicative gene transcription and its control (Cresawn et al., 2007).) These genes include A18R, which encodes a negative transcription elongation factor, and G2R and J3R, which encode positive transcription elongation factors (Black and Condit, 1996; Xiang et al., 1998; Latner et al., 2000). In addition, viral RNA polymerase mutants have been isolated that are altered in their elongation properties in a fashion that impacts on late transcription (Condit et al., 1991; Prins et al., 2004; Cresawn et al., 2007). Lastly, the product of the vaccinia gene H5R is also implicated in postreplicative gene transcription elongation by virtue of its association with the G2 protein (Black et al., 1998).

Identification of genes that influence vaccinia postreplicative gene transcription has been aided significantly by isolation and characterization of virus mutants that are dependent upon or resistant to the antipoxviral drug, isatin-β-thiosemicarbazone (IBT). Although the precise mechanism of action of IBT is unknown, addition of the drug to wild type vaccinia virus infections results in synthesis of postreplicative mRNA transcripts that are longer than normal, presumably because of enhanced transcription elongation or inhibition of transcription termination (Bayliss and Condit, 1993; Xiang, 1998). IBT dependent mutants have been isolated in the positive transcription elongation factor genes G2R and J3R, and IBT resistant mutants have been isolated in genes G2R, J3R and in the genes encoding the largest two subunits of the viral RNA polymerase, rpo147 (J6R) and rpo132 (A24R) (Condit et al., 1991; Meis and Condit, 1991; Hassett and Condit, 1994; Condit et al., 1996; Latner et al., 2000; Cresawn et al., 2007). G2R and J3R mutants that are IBT dependent synthesize severely 3' truncated and therefore nonfunctional postreplicative RNAs, preventing virus growth in the absence of drug; addition of IBT to cells infected with dependent mutants promotes extension of the postreplicative viral mRNA 3' ends to restore functionality to the RNAs and growth of the virus (Black and Condit, 1996; Latner et al., 2000). The molecular defect in IBT resistant mutants is more subtle. IBT resistant RNA polymerase mutants are defective in transcription elongation in vitro, and we believe that in vivo, IBT resistant mutants synthesize slightly shorter than normal postreplicative RNAs, thus compensating for the elongation-promoting effects of IBT (Condit et al., 1991; Hassett and Condit, 1994; Latner et al., 2002; Cresawn et al., 2007).

To date, genes which modify the response of vaccinia to IBT have been identified primarily by genetic characterization of spontaneous IBT resistant or dependent mutants. While this effort has been informative, it ultimately approaches a point of diminishing returns since the majority of mutants isolated map to genes that are particularly susceptible to mutation to IBT resistance or dependence. However the catalogue of factors that influence vaccinia posttranscriptional elongation is probably incomplete. IBT resistant mutants have been isolated which are recalcitrant to genetic mapping yet do not affect the known elongation factors (Cresawn et al., 2007), and additional vaccinia proteins have been identified, for example H5, which are implicated in transcription elongation by virtue of association with elongation factors, but have not been proven to influence elongation in vivo using genetic criteria (Black et al., 1998). Therefore, in an attempt to expand the catalogue of elongation factors and probe the involvement of additional genes in transcription elongation, we have used targeted mutagenesis to determine whether IBT resistant mutants can be isolated in specific candidate elongation factor genes. We present here proof of principle for the targeted approach by isolation of new IBT resistance alleles in previously identified genes and evidence that the H5R gene product plays a role in postreplicative gene transcription.

Results

Isolation of novel IBT resistant mutants using error prone PCR

Error-prone PCR and marker rescue in the presence of IBT were combined to screen several genes for possible roles in intermediate and late transcription elongation. In this experiment, cells were infected with the temperature sensitive Dts38 helper virus, co-transfected with wild-type genomic DNA and a PCR product corresponding to an open reading frame to be tested, and incubated at 37°C in the presence of IBT. These conditions select against growth of wild type or helper virus, and select for IBT resistant viruses formed by recombination of mutations from the transfected PCR product into the co-transfected wild type genomic DNA (Cresawn et al., 2007). The PCR product was generated in both a high-fidelity PCR protocol (control) and an error-prone PCR protocol (experimental). A positive result in this experiment was indicated by a higher number of plaques on cells transfected with the error-prone PCR product compared to cells transfected with the high-fidelity PCR product from the same gene.

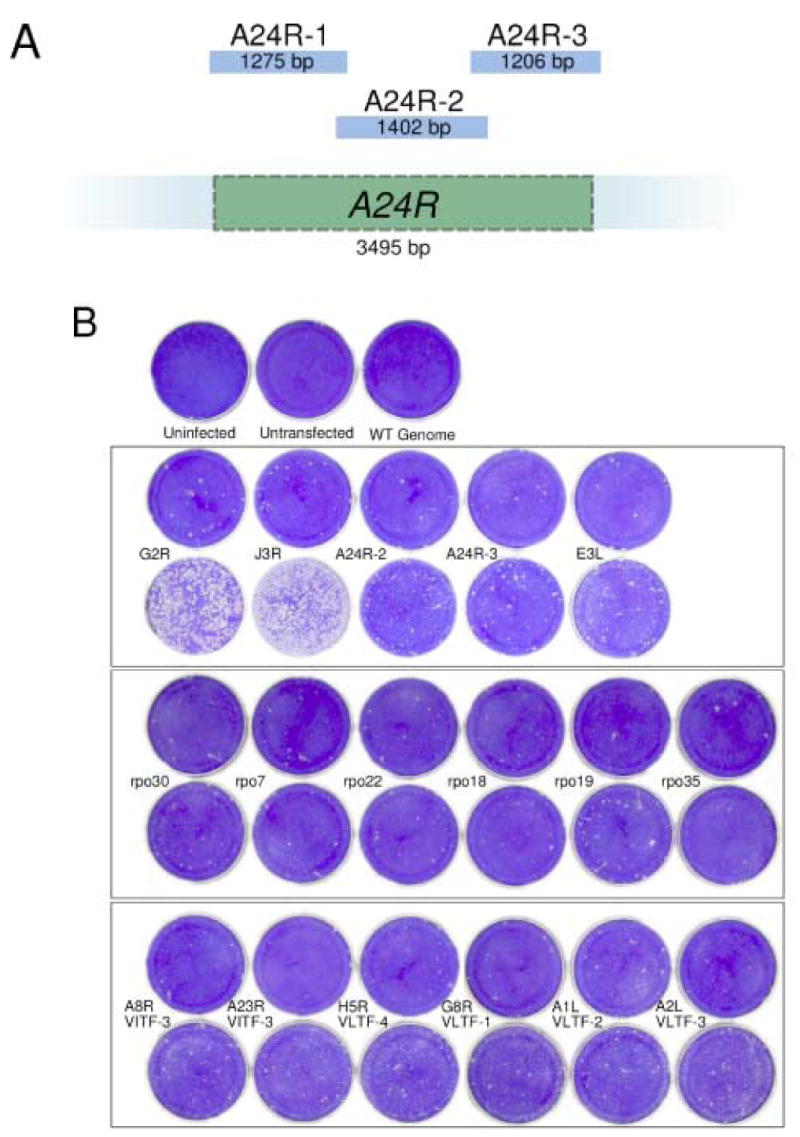

The G2R, J3R and A24R genes were tested in the error prone PCR and marker rescue protocol as positive controls. The G2R and J3R genes were expected to produce the strongest signal, because any mutation that inactivates either gene results in an IBT dependence phenotype (Meis and Condit, 1991; Latner et al., 2000) and therefore should produce a virus capable of growing in the presence of IBT. The A24R gene, which encodes the second largest subunit of the viral RNA polymerase, rpo132, served as a more stringent positive control. Previous mapping of IBTr90 to rpo132 indicated that it should be possible to construct an IBT-resistant mutant in A24R (Condit et al., 1991). Preliminary experiments indicated that the efficiency of amplification of sequences longer than about 2 kbp was decreased in the error-prone PCR format. For this reason, A24R was divided into three overlapping segments ranging from 1.2 kbp to 1.5 kbp in length, designated A24R-1, A24R-2, and A24R-3 from the 5' to 3' end (Fig. 1A). A pilot experiment (not shown) indicated that the 5'-most fragment was the least likely to produce a signal and therefore it was not included in further experiments.

Fig. 1. Targeted mutagenesis and selection for IBT resistance.

A) A diagram showing the three overlapping fragments, A24R-1, A24R-2 and A24R-3, that were amplified from the A24R gene. B) Marker rescue with error prone PCR fragments. Confluent dishes of BSC40 cells were infected with Dts38 and co-transfected with wild-type genomic DNA and the indicated PCR product. Controls are shown in the top row: “Uninfected” was neither infected nor transfected. “Untransfected” was infected with Dts38 but not transfected. “WT genome” was infected with Dts38 and transfected with wild type genomic DNA alone. In each of the bottom three boxed panels, the top row contains negative controls, transfected with the indicated high-fidelity PCR product, while the bottom row contains dishes transfected with the indicated error-prone PCR product. After a 4 day incubation at 37°C in the presence of IBT, dishes were stained with crystal violet.

The genes chosen as candidates for targeted mutagenesis to IBT resistance were several with known roles in RNA binding or synthesis. These included six RNA polymerase subunits (rpo7 [G5.5R], rpo18 [D7R], rpo19 [A5R], rpo22 [J4R], rpo30 [E4L] and rpo35 [A29R]), the dsRNA-binding protein (E3L), the intermediate transcription initiation factors (VITF-1 [E4L] and VITF3 [A8R + A23R]), the late transcription initiation factors (VLTF-1 [G8R], VLTF-2 [A1L], and VLTF3 [A2L]) and the late transcription stimulatory factor (VLTF-4 [H5R]).

Results from the error prone PCR and marker rescue experiment are shown in Fig. 1B. As expected, the strongest signal detected in this experiment was with the G2R or J3R genes. However, a clear signal over background was also observed with A24R-2, A24R-3, and rpo19 (A5R). Weaker signals over background were observed with a number of other genes, including E3L, A8R and A23R (VITF-3), H5R (VLTF-4), A1L (VLTF-2), and A2L (VLTF-3). The strong signal observed after mutagenesis and transfection of G2R and J3R indicates that the error prone PCR indeed induces IBT resistance mutations that can be efficiently incorporated into the vaccinia genome using the marker rescue and selection protocol described. Therefore these positive controls, plus the stringent positive control, rpo132 (A24R) and several of the test genes were analyzed further.

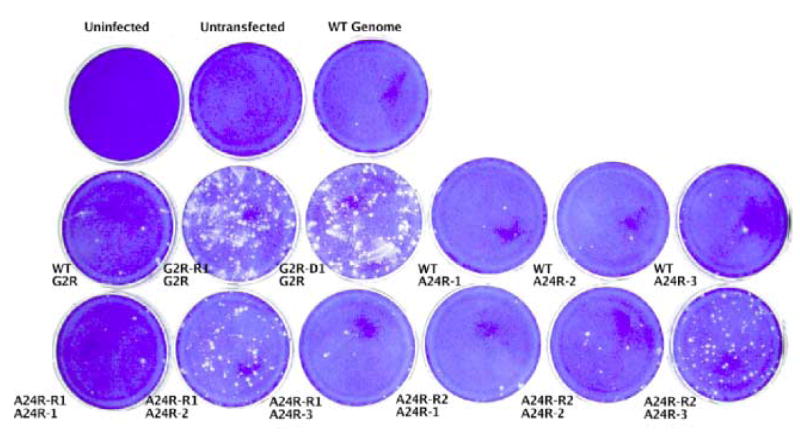

To determine whether plaques formed on the dishes transfected with error prone PCR products arose as a result of errors in those PCR products, two plaques were picked for study from each of the G2R, A24R-2, and A24R-3 dishes from an agar-overlaid experiment otherwise identical to the one shown in Fig. 1. The resulting presumptive G2R mutant viruses were named G2R-R1 and G2R-D1; one presumptive A24R mutant virus resulting from mutagenesis of the A24R-2 DNA fragment was named A24R-R1, and one presumptive A24R mutant virus resulting from mutagenesis of the A24R-3 fragment was named A24R-R2. The viruses in these plaques were plaque purified to ensure that no contaminating helper virus was present and that the stocks were genetically homogeneous. The plaque purified viruses were grown, and viral DNA was then extracted from lysates for use as a PCR template. The gene or gene fragment targeted in the original error-prone PCR experiment, G2R, A24R-2 or A24R-3, was PCR amplified from each mutant using the high-fidelity protocol for use in a marker-rescue experiment. In the case of the A24R-targeted mutants, the other two fragments of the A24R gene were also amplified to ensure that they did not contain mutations. The results are shown in Fig. 2. Transfections using high fidelity PCR fragments representing G2R or A24R amplified from wild type DNA templates yielded a background level of plaque formation (Fig. 2, middle row, “WT G2R”, “WT A24R-1”, “WT A24R-2”, “WT A24R-3”). Transfections using high fidelity PCR fragments amplified from the presumptive G2R mutants G2R-R1 and G2R-R2 yielded a significantly higher number of plaques compared to control WT G2R background (Fig. 2, compare “G2R-R1 G2R” and “G2R-D1 G2R” with “WT G2R”). Likewise, when the A24R-2 or A24R-3 regions of the A24R gene were targeted for mutagenesis, the appropriate fragments amplified from the reconstructed mutants rescued IBT resistance into WT virus in the infection/transfection experiment (compare dishes “A24R-R1 A24R-2” with “WT A24R-2” and “A24R-R2 A24R-3” with “WT A24R-3”), whereas the untargeted fragments did not (compare “A24R-R1 A24R-1” or “A24R-R1 A24R-3” with “A24R-R1 A24R-2” and “A24R-R2 A24R-1” or “A24R-R2 A24R-2” with “A24R-R2 A24R-3”). In summary, this experiment proves that the error prone PCR did indeed result in mutation of the targeted fragment to create an IBT resistance allele.

Fig. 2. G2R and A24R mutants constructed by error-prone PCR mutagenesis map to the targeted gene or gene fragment.

Confluent dishes of BSC40 cells were infected with the Dts38 helper virus and co-transfected with wild-type genomic DNA (“WT genome”) and the indicated PCR product. After a 4 day incubation at 37°C in the presence of IBT, dishes were stained with crystal violet.

To analyze the genotype of the G2R and A24R mutants, the targeted gene in each mutant was sequenced. The results are shown in Table 1. Sequencing the G2R-targeted mutants revealed a single missense mutation of the G2R gene of G2R-R1 and a frameshift in G2R-D1. G2R-D1 contains a second downstream mutation which would encode a missense substitution in the native protein, but is rendered irrelevant because of the upstream frameshift. Sequencing of the A24R-targeted mutants revealed a single missense mutation in each virus in the appropriate fragment but no mutations in the other fragments. The A24R-R2 virus contains an additional silent mutation. To confirm these results, the marker rescue experiment shown in Fig. 3 was repeated using an agar overlay and a plaque was picked from each of the G2R-R1, G2R-D1, A24R-R1, and A24R-R2 transfections. Viruses in each picked plaque were grown under IBT selection and plaque purified. DNA was extracted from a viral lysate, and the gene targeted by error-prone PCR was amplified and sequenced, confirming the presence of the mutations reported in Table 1. These reconstructed viruses were designated G2R-R1R, G2R-D1R, A24R-R1R, and A24R-R2R.

Table 1.

Genotypes of error-prone PCR mutants

| Virus | Gene | DNAa | Proteina,b |

|---|---|---|---|

| G2R-R1 | G2R | T197C | L66S |

| G2R-D1 | G2R | A303-; (A538G) | fs 101, term 103; (I180V) |

| A24R-R1 | A24R | T1384C | Y462H |

| A24R-R2 | A24R | (T2526A); A2650G | (V842V); T884A |

| H5R-R1 | H5R | (A93T); A107T | (N31K), D36V |

Irrelevant mutations are shown in parentheses.

fs = frameshift; term = translation termination codon

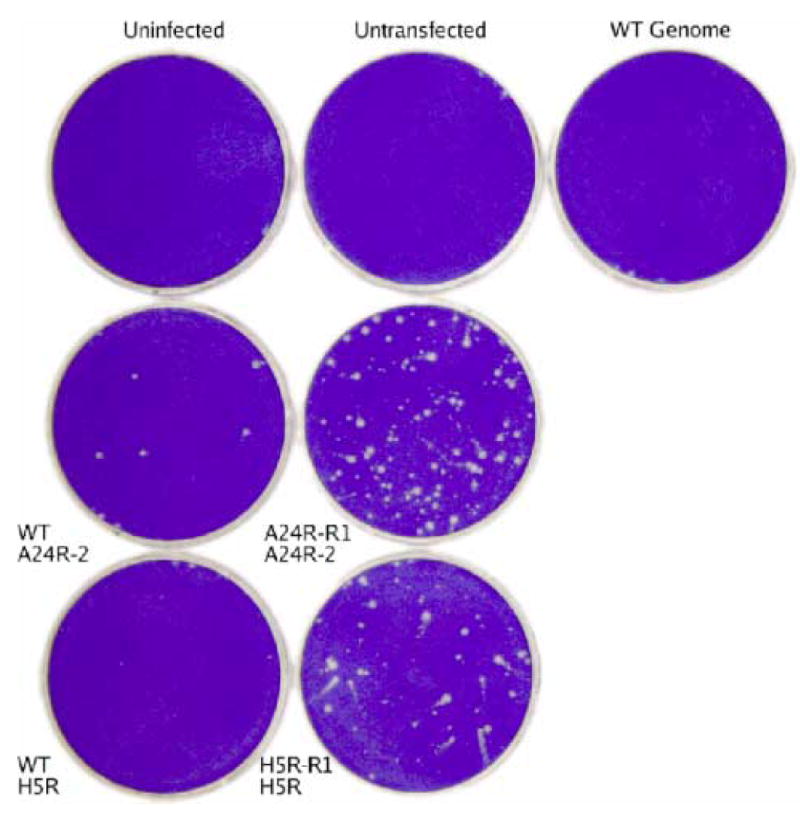

Fig. 3. Marker rescue of the H5R-R1 mutation.

Confluent dishes of BSC40 cells were infected with the Dts38 helper virus and co-transfected with wild-type genomic DNA (“WT Genome”) and the indicated PCR product. After a 4 day incubation at 37°C in the presence of IBT, dishes were stained with crystal violet.

The screen of several vaccinia virus genes for their potential to give rise to IBT-resistant or IBT-dependent mutants identified a number of genes with weak positive signals (Fig. 1). From those genes with positive signals, three were chosen for further study. These three genes (VLTF3 [A2L], rpo19 [A5R], and H5R) were chosen because they encode proteins that differ from one another with respect to their biochemical activities and known roles in transcription. Of the three genes, H5R is of particular interest due to its known association with the G2 elongation factor (Black et al., 1998). In an attempt to isolate IBT-resistant or IBT-dependent A2L, A5R, and H5R mutants, error-prone PCR products amplified from a wild type viral DNA template in triplicate and corresponding to each of these three genes were co-transfected with wild type genomic DNA into Dts38 helper infected cells in the presence of IBT. Each of the three H5R transfections and one each of the A2L and A5R transfections resulted in a cytopathic effect (CPE). Once the CPE was complete, infected cell lysates were harvested. Viruses in these lysates were plaque purified, grown, viral DNA was isolated and the gene targeted in the error-prone PCR (A2L, A5R, or H5R) was PCR amplified and sequenced. The A2L-targeted and A5R-targeted mutants each contained a silent mutation in their targeted gene, while two of the three H5R-targeted mutants contained the wild type H5R sequence (data not shown). This result indicates that the IBT resistance in these viruses arose via spontaneous mutation at a locus other than the targeted locus. However, the remaining H5R mutant, designated H5R-R1, contains two missense mutations in H5R (Table 1), suggesting that targeted mutation of H5R may have given rise to IBT resistance.

To test whether the missense H5R mutations in H5R-R1 confer IBT resistance, a marker rescue experiment was done. The H5R gene was amplified by high fidelity PCR using H5R-R1 viral DNA as a template, and the amplified product was co-transfected along with wild type DNA into Dts38 helper virus infected cells, and placed under selection for IBT resistance. A control experiment using the A24R-2 DNA fragment from the IBT resistant mutant A24R-R1 was done in parallel. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Transfections with H5R or A24R fragments amplified from wild type DNA yielded background levels of plaque formation relative to uninfected, untransfected, or wild type genome transfected controls (Fig 3, compare top row with “WT A24R-2” or WT H5R”.) Importantly, transfection with the H5R fragment amplified from H5R-R1 yielded a significant signal over this background, similar to the positive A24R gene control (Fig. 3, compare “H5R-R1 H5R” with “A24R-R1 A24R-2”.) Finally, a transfection with the H5R gene from H5R-R1 identical to the experiment shown in Fig. 3 was done using an agar overlay so that IBT resistant virus could be isolated and characterized. Three plaques were picked, grown under IBT selection, and plaque purified. The H5R gene from these three viruses was sequenced. In two cases, the viruses contained both the K31N and D36V mutations found in H5R-R1 (Table 1). However the H5R gene of the third virus contained only the D36V mutation. The reconstructed virus containing this single H5R mutation was designated H5R-R1R. Together these results prove that the D36V mutation in the H5R gene confers IBT resistance to vaccinia virus.

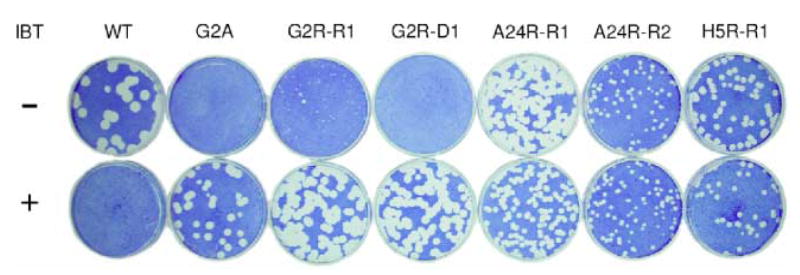

The viruses isolated by the error-prone PCR/marker rescue strategy are capable of growth in the presence of IBT, however this observation does not distinguish between IBT-resistance and IBT-dependence. In order to make such a distinction, a plaque assay was done with each mutant using the IBT-sensitive wild-type and the IBT-dependent G2A viruses as controls (Fig. 4). This experiment reveals that G2R-R1 is weakly IBT resistant, while G2R-D1 is IBT dependent. The IBT dependence phenotype of G2R-D1 is consistent with its null mutant genotype (Table 1). Importantly, the plaque assay also shows that both of the A24R mutants and the H5R mutant are IBT-resistant.

Fig. 4. Plaque phenotypes of mutant viruses.

Confluent monolayers of BSC40 cells in 6 cm dishes were infected with appropriate dilutions of WT virus and the indicated mutants. The dishes were incubated at 37°C for 6 days in the presence and absence of IBT prior to staining with crystal violet.

Phenotypic characterization of the A24R and H5R mutants

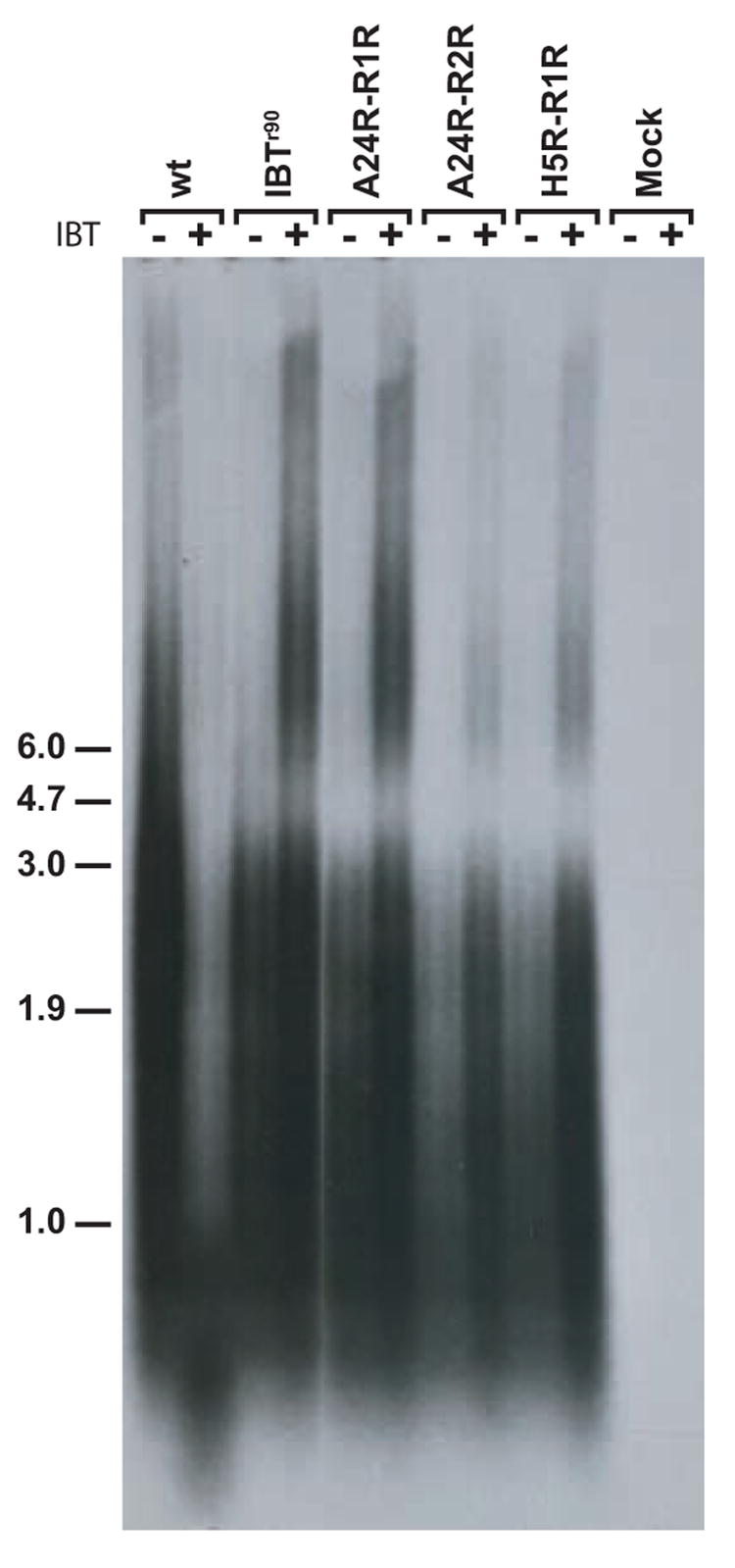

To gain insight into the mechanism of IBT resistance in the newly isolated A24R and H5R mutants, postreplicative viral mRNA synthesis was assessed using northern blot analysis. Cells were infected with wt virus, the control IBT resistant virus IBTr90, or the reconstructed IBT resistant mutant viruses A24R-R1R, A24R-R2R and H5R-R1R. RNA was isolated from infected cells at 9 h post infection, fractionated by denaturing agarose gel elctrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, and the blot was probed with a riboprobe specific for the late A10L gene (Fig. 5). In the absence of IBT, the wt virus infection revealed the heterogeneous population of transcripts characteristic of postreplicative vaccinia RNAs. Viral RNAs produced in the absence of IBT in the mutant infections were indistinguishable from wt viral RNAs. In the presence of IBT, wt transcripts reach a length sufficient to induce the 2-5 A pathway, resulting in RNA degradation revealed as a low molecular weight smear in the northern blot (Pacha and Condit, 1985; Cohrs et al., 1989; Bayliss and Condit, 1993; Xiang, 1998). In the presence of IBT, all of the mutant infections produce viral RNAs that were increased in length compared to infections done in the absence of drug. The mutant infections also produced apparently more viral RNA in the presence of IBT compared to the infections done in the absence of drug. This quantitative effect likely results from excess readthrough into the A10L gene from upstream postreplicative genes. Consistent with the northern analysis, rRNA visualized by ethidium bromide staining of these same gels before transfer reveals rRNA breakdown in wild type infections done in the presence of IBT, while in all other infections rRNA remained intact. In summary, during infection with each of the viruses tested, addition of IBT to the infections resulted in synthesis of longer transcripts compared to infections done in the absence of drug.

Fig. 5. Northern analysis of IBT-resistant mutant RNA.

Confluent BSC40 cells were infected with the indicated virus at m.o.i. = 15 in the presence or absence of IBT and incubated at 37°C for 9 hours. Total cellular RNA was purified, fractionated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane. The membrane was probed with a riboprobe specific for the late A10L gene and exposed to film. The virus used for infection is indicated at the top of the autoradiogram. The presence of absence of IBT in the infection is indicated with a “+” or a “−” at the top of the autoradiogram. Size markers are indicated at the left of the autoradiagram, in kb.

Discussion

Error-prone PCR coupled with marker rescue constitutes a viable strategy for extending the number of known genes involved in intermediate and late transcription elongation. This was shown by the construction of IBT-resistant and IBT-dependent mutants with random mutations in the specifically targeted genes G2R, A24R, and H5R. While the G2R and A24R mutants serve as a proof-of-concept, these IBT-resistant mutants additionally should prove useful for the study of the G2R and A24R gene products themselves. Also, a screen of other potentially interesting genes has uncovered several that warrant further study. These include the small RNA polymerase subunit A5R (rpo19), the intermediate initiation factors A8R and A23R, the late initiation factors A1L and A2L, and the dsRNA-binding protein E3L. Most importantly, a mutant mapping to the H5R gene and capable of growth in the presence of IBT has been identified. This result validates the error-prone PCR/marker rescue approach for the screening of genes for their involvement in transcription and provides strong genetic evidence to link H5R to the intermediate and late transcription control system.

Interestingly, the previously characterized A24R IBT resistant mutant, IBTr90, (Condit et al., 1991; Prins et al., 2004) and the new A24R-R1 mutant share the same genotype. Each has a tyrosine to histidine substitution at position 462. This situation is similar to that observed with the spontaneous mutants DL1-3 and DL10-7, which are an identical pair of rpo147 mutants (Cresawn et al., 2007). These observations suggest that the residues involved in these mutations may be critically important for controlling elongation. They also suggest that there may a relatively small number of possible polymerase mutations that can lead to IBT-resistance.

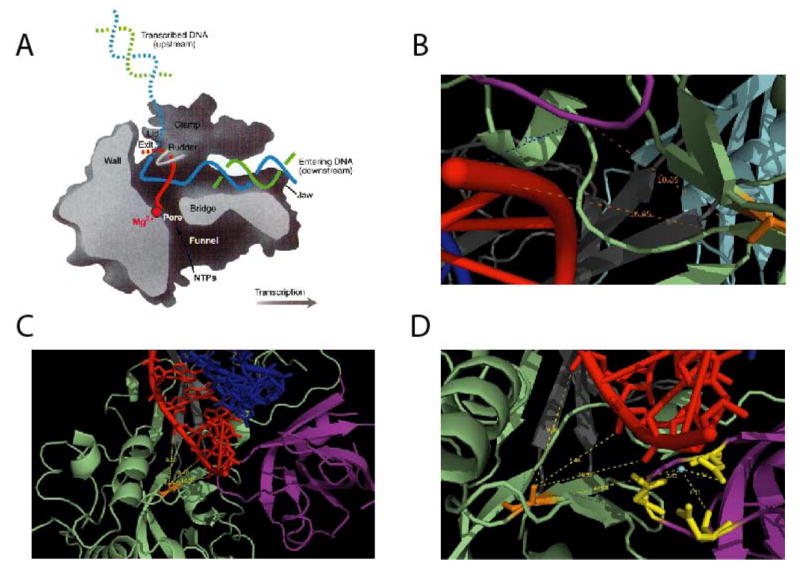

A homology model of rpo132 previously constructed to analyze spontaneous IBT-resistant mutants (Prins et al., 2004) was used to approximate the location of the new A24R-R1 and A24R-R2 mutations on the protein's structure (Fig. 6). As noted above, IBTr90 and A24R-R1 have in common a single point mutation (Y462H). According to our homology model, Y462 in rpo132 is equivalent to L514 in yeast rpb2. This residue is thought to reside at the base of fork loop 2, a region implicated in maintaining the open conformation of the downstream edge of the transcription bubble (Gnatt et al., 2001). The Y462H mutation has been shown previously to impede elongation by the mutant RNA polymerase in vitro (Prins et al., 2004). Such an effect could theoretically compensate for the elongation enhancing effects of IBT in vivo. The A24R-R2 mutation affects residue T884 in rpo132, which is equivalent to A981 in yeast rpb2. Thus the A24-R2 mutation is located in a region of the modeled polymerase that is well-conserved between vaccinia and S. cerevisiae RNA polymerase II. In the latter, this region interacts with the DNA/RNA hybrid. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the A24R-R2 mutation weakly destabilizes the DNA/RNA hybrid by disrupting contacts with the polymerase. This model would predict decreased transcriptional processivity, as has been observed in other IBT-resistant mutants (Cresawn et al., 2007).

Fig. 6. Structural modeling of A24-R1 and A24-R2.

A model of the vaccinia rpo312 (gene A24R) subunit was constructed based on homology to the known structure of S. cerevisiae RNA polymerase II subunit rpb2 (Prins et al., 2004). Yeast RNA polymerase residues homologous to the mutant vaccinia alleles were then highlighted on the structure of the elongating yeast RNA polymerase. A) Side (cutaway) view of the RNA polymerase II transcribing complex. The template DNA strand is in blue, the nontemplate DNA strand is in green, and the RNA is in red. Additional structural features of the enzyme are indicated. B-D) Close up views of the yeast RNA polymerase II active site, with residues homologous to the A24R mutations highlighted in orange. The figures show distances in angstroms from the mutant residue to the 3′ end of the RNA, and in D, from the catalytic Mg++ to three conserved active site aspartic acid residues and the mutation. B) A24R-R1 (yeast L514). C and D) A24R-R2 (yeast T884). Colors indicate the following: mutant residue, orange; active site, purple; wall, grey; hybrid binding, green; RNA, red; DNA, blue A) is from Klug (2001).

The primary effect of IBT on a wt virus infection is to cause synthesis of 3' extended viral RNAs, theoretically either by stimulating transcription elongation or by inhibiting transcription termination. We have previously suggested two likely mechanisms for IBT resistance: 1) inhibition of drug binding or 2) compensation via decreased transcription elongation. Northern blot analysis revealed a phenotype for the A24R and H5R IBT resistant mutants that is identical to the phenotype previously reported for IBT resistant mutants in G2R and J6R (rpo132; the second largest subunit of the viral RNA polymerase) (Cresawn et al, 2007). Specifically, all of the IBT resistant viruses responded to addition of IBT by synthesizing viral RNAs that were increased in length relative to infections done in the absence of drug. Therefore none of the mutants are defective in drug binding. Based on these findings we propose that the A24R and H5R mutants reported here are compensatory mutants, that is, they are sufficiently elongation defective to compensate for the effects of IBT, without at the same time seriously compromising the infection done in the absence of drug. The elongation defects are theoretically too subtle to be detected by northern blotting, owing to the extreme heterogeneity of the postreplicative viral RNAs. In support of the compensatory model, prior characterization of other IBT resistant mutants in the RNA polymerase, including IBTr90, which has a genotype identical to A24-R1, has revealed transcription elongation defects in vitro (Prins et al 2006; Cresawn et al, 2007). Ultimate proof of the compensatory model awaits an in vitro assay for the presumed elongation activity of H5 and other elongation factors, G2 and J3.

Isolation of an IBT resistant mutant in the H5R gene, H5R-R1, provides in vivo evidence linking the H5 protein to a role in transcription elongation. Previous studies have implicated H5 in a wide variety of processes during viral infection. The H5 protein has a predicted molecular weight of 22 kDa, but runs anomalously at 34 kDa on SDS gels. H5 is a substrate for the vaccinia virus coded B1 serine/threonine protein kinase and is multiply phosphorylated in vivo (Beaud et al., 1995; Brown et al., 2000; Beaud and Beaud, 2000; Boyle and Traktman, 2004). The H5 protein is synthesized in abundance throughout infection (Rosel et al., 1986); at early times is it distributed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm while at later times it is concentrated into virosomes and is ultimately packaged into virions (Beaud and Beaud, 1997; Murcia-Nicolas et al., 1999; Domi and Beaud, 2000). Biochemical experiments have implicated H5 in both DNA replication and transcription. With respect to DNA replication, H5 has been shown to interact with the DNA polymerase processivity factor, A20, and with the B1 kinase, which is required for DNA replication (McCraith et al., 2000). With respect to transcription, H5 stimulates transcription from a late viral promoter in vitro, and it has been shown to interact with the late transcription factors VTLF-1 (G8) and VTLF-3 (A2), and with the postreplicative transcription elongation factor G2 (Kovacs and Moss, 1996; Black et al., 1998; Dellis et al., 2004). H5 also interacts with at least one other protein of unknown function (McCraith et al., 2000). One temperature sensitive mutant in the H5R gene has previously been characterized; interestingly, the mutant displays no detectable defects in viral DNA replication or late gene expression, but instead displays a severe defect in the earliest stages of morphogenesis (DeMasi and Traktman, 2000). Our discovery of an H5 mutant with a phenotype previously associated with G2R mutants (IBT-resistance or IBT-dependence) is consistent with previously reported biochemical experiments implicating H5 in late transcription; it reinforces the significance of the G2-H5 interaction and suggests that H5 may either play a direct role in transcription elongation or may influence G2 function in transcription elongation in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses; marker rescue; DNA sequencing; northern blotting

Sources and handling of cells and viruses, and techniques for marker rescue, DNA sequencing and northern blotting are described in the companion manuscript (Cresawn et al, 2007). Agarose gels for the northern blots were run at 35 v for 17 h with continuous recirculation of buffer.

Polymerase chain reaction

Isolation of DNA for use as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template, and high fidelity PCR was performed as described in the companion manuscript (Cresawn et al., 2007). Error-prone PCR was performed in the same fashion, with three exceptions: 1) Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase was used in place of Deep Vent DNA polymerase, 2) the final concentration of dNTPs in the reaction mixture was unequal, with ATP and GTP at a concentration of 100 μM and CTP and TTP at a concentration of 500 μM. 3) MnCl2 was introduced into the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 150 μM.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI18094 to RCC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bayliss CD, Condit RC. Temperature-sensitive mutants in the vaccinia virus A18R gene increase double-stranded RNA synthesis as a result of aberrant viral transcription. Virology. 1993;194:254–262. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaud G, Beaud R. Preferential virosomal location of underphosphorylated H5R protein synthesized in vaccinia virus-infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 12):3297–3302. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaud G, Beaud R. Temperature-dependent phosphorylation state of the H5R protein synthesised at the early stage of infection in cells infected with vaccinia virus ts mutants of the B1R and F10L protein kinases. Intervirology. 2000;43:67–70. doi: 10.1159/000025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaud G, Beaud R, Leader DP. Vaccinia virus gene H5R encodes a protein that is phosphorylated by the multisubstrate vaccinia virus B1R protein kinase. J Virol. 1995;69:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1819-1826.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black EP, Condit RC. Phenotypic characterization of mutants in vaccinia virus gene G2R, a putative transcription elongation factor. J Virol. 1996;70:47–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.47-54.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black EP, Moussatche N, Condit RC. Characterization of the interactions among vaccinia virus transcription factors G2R, A18R, and H5R. Virology. 1998;245:313–322. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle KA, Traktman P. Members of a novel family of mammalian protein kinases complement the DNA-negative phenotype of a vaccinia virus ts mutant defective in the B1 kinase. J Virol. 2004;78:1992–2005. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1992-2005.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NG, Nick MD, Beaud G, Hardie G, Leader DP. Identification of sites phosphorylated by the vaccinia virus B1R kinase in viral protein H5R. BMC Biochem. 2000;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs RJ, Condit RC, Pacha RF, Thompson CL, Sharma OK. Modulation of ppp(A2′p)nA-dependent RNase by a temperature-sensitive mutant of vaccinia virus. J Virol. 1989;63:948–951. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.2.948-951.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit RC, Easterly R, Pacha RF, Fathi Z, Meis RJ. A vaccinia virus isatin-beta-thiosemicarbazone resistance mutation maps in the viral gene encoding the 132-kDa subunit of RNA polymerase. Virology. 1991;185:857–861. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90559-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit RC, Niles EG. Regulation of viral transcription elongation and termination during vaccinia virus infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:325–336. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit RC, Xiang Y, Lewis JI. Mutation of vaccinia virus gene G2R causes suppression of gene A18R ts mutants: implications for control of transcription. Virology. 1996;220:10–19. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresawn SG, Prins C, Latner D, Condit RC. Mapping and phenotypic analysis of spontaneous isatin-β-thiosemicarbazone resistant mutants of vaccinia virus. Virology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.005. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellis S, Strickland KC, McCrary WJ, Patel A, Stocum E, Wright CF. Protein interactions among the vaccinia virus late transcription factors. Virology. 2004;329:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMasi J, Traktman P. Clustered charge-to-alanine mutagenesis of the vaccinia virus H5 gene: isolation of a dominant, temperature-sensitive mutant with a profound defect in morphogenesis. J Virol. 2000;74:2393–2405. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2393-2405.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domi A, Beaud G. The punctate sites of accumulation of vaccinia virus early proteins are precursors of sites of viral DNA synthesis. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1231–1235. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-5-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu J, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001;292:1876–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett DE, Condit RC. Targeted construction of temperature-sensitive mutations in vaccinia virus by replacing clustered charged residues with alanine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4554–4558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug A. Structural biology. A marvellous machine for making messages. Science. 2001;292:1844–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1062384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs GR, Moss B. The vaccinia virus H5R gene encodes late gene transcription factor 4: purification, cloning, and overexpression. J Virol. 1996;70:6796–6802. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6796-6802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner DR, Thompson JM, Gershon PD, Storrs C, Condit RC. The positive transcription elongation factor activity of the vaccinia virus J3 protein is independent from its (nucleoside-2′-O-) methyltransferase and poly(A) polymerase stimulatory functions. Virology. 2002;301:64–80. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner DR, Xiang Y, Lewis JI, Condit J, Condit RC. The vaccinia virus bifunctional gene J3 (nucleoside-2′-O-)- methyltransferase and poly(A) polymerase stimulatory factor is implicated as a positive transcription elongation factor by two genetic approaches. Virology. 2000;269:345–355. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCraith S, Holtzman T, Moss B, Fields S. Genome-wide analysis of vaccinia virus protein-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4879–4884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis RJ, Condit RC. Genetic and molecular biological characterization of a vaccinia virus gene which renders the virus dependent on isatin-beta-thiosemicarbazone (IBT) Virology. 1991;182:442–454. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90585-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murcia-Nicolas A, Bolbach G, Blais JC, Beaud G. Identification by mass spectroscopy of three major early proteins associated with virosomes in vaccinia virus-infected cells. Virus Res. 1999;59:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacha RF, Condit RC. Characterization of a temperature-sensitive mutant of vaccinia virus reveals a novel function that prevents virus-induced breakdown of RNA. J Virol. 1985;56:395–403. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.2.395-403.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins C, Cresawn SG, Condit RC. An isatin-beta-thiosemicarbazone-resistant vaccinia virus containing a mutation in the second largest subunit of the viral RNA polymerase is defective in transcription elongation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44858–44871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosel JL, Earl PL, Weir JP, Moss B. Conserved TAAATG sequence at the transcriptional and translational initiation sites of vaccinia virus late genes deduced by structural and functional analysis of the HindIII H genome fragment. J Virol. 1986;60:436–449. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.436-449.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y. Ph D Thesis. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Simpson DA, Spiegel J, Zhou A, Silverman RH, Condit RC. The vaccinia virus A18R DNA helicase is a postreplicative negative transcription elongation factor. J Virol. 1998;72:7012–7023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7012-7023.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]