Abstract

In this study, 80 Candida glabrata isolates from intensive care unit and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients were typed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and mating type class determination. Among the 25 patients with multiple isolates, 19 patients (76%) contained multiple isolates exhibiting identical or highly related PFGE and MLST genotypes, which may indicate the maintenance or microvariation of one C. glabrata strain in each patient. However, isolates from six patients (24%) displayed different sequence types, PFGE genotypes, or mating type classes, which may indicate colonization with more than one clone over time or strain replacement. High correlations among PFGE genotypes, sequence types, and mating types were found (P < 0.01). MLST exhibited less discriminatory power than PFGE with BssHII. The genotypes, sequence types, and mating type classes were independent of anatomic sources, drug susceptibility, and HIV infection status.

Candida species are the most common opportunistic pathogens in debilitated or immunocompromised hosts and cause systemic candidiasis, which has high rates of morbidity and mortality (20, 21, 28, 44). Since 1993, Candida species have become the leading pathogens responsible for nosocomial bloodstream infections in a large teaching hospital in Taiwan (9). Candida glabrata has become the second or third most common cause of candidemia (19, 24, 34, 43), and the prevalence of C. glabrata infections has increased in the last decade (9, 13, 21, 31).

Nosocomial Candida infection was found to be an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients in intensive care units (11), and it represents a factor which might be modified to improve the quality of care and pathological outcomes for patients. It is therefore paramount to elucidate the pathogenesis of nosocomial Candida infection in order to establish an effective health care policy for prevention and management. Because Candida species can be carried as commensal organisms, intraspecies delineation is essential for determination of the route of transmission.

Of a variety of DNA fingerprinting methods that have been investigated, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) allows the resolution and reproducible separation of DNA of chromosomal size in Candida yeasts; the results of PFGE have been shown to have high rates of interlaboratory agreement (18), and PFGE has been used to analyze the relatedness of C. glabrata strains (10, 23). Recently, the use of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has been proposed to meet the increasing need for global surveillance and comparison of genotypes in a central database via the Internet. MLST of pathogenic fungal species has been developed to study population structures, such as those of Candida albicans (3, 4, 6), Candida tropicalis (12, 42), and Candida krusei (27). A set of six genes encoding housekeeping functions, comprising the fragments FKS, LEU2, NMT1, TRP1, UGP1, and URA3, is recommended for MLST with C. glabrata (http://cglabrata.mlst.net/) (16).

Previous genotyping studies indicated that unique or multiple strains of C. albicans from longitudinal surveys or different anatomical sites of the same patient persisted in each human host (6, 10, 33). Genetic typing of C. glabrata could provide information on strain variation, such as replacement, microvariation, microevolution, and maintenance, to track its distribution in the host (6, 33). Four mating type classes were previously described in C. glabrata, namely, classes I, II, III, and IV (39). It was demonstrated that the different mating type classes could be involved in the pathogenesis or drug resistance of C. albicans (5, 37, 38).

In this study, we used MLST and PFGE to assess the clonality of C. glabrata and to ascertain whether different characteristics (e.g., drug resistance, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection status, patient characteristics, and anatomic origin) could be attributed to specific genotypes and to assess the usefulness of the MLST and PFGE methods in tracing colonization/infection and relapse/reinfection, as well as polyclonal infections in different body sites. Another purpose of this study was to evaluate the power of fingerprinting by MLST and PFGE with BssHII in delineating strains of C. glabrata.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains.

A total of 80 C. glabrata clinical isolates were collected from 37 patients during active surveillance at a teaching hospital in Taiwan. Fifty-six isolates were collected from 27 intensive care unit patients during 1996 and 1997 (10). The isolates that were superficial colonizers were collected from anal swabs (30 isolates), stool specimens (2 isolates), sputum specimens (9 isolates), throat swab specimens (3 isolates), and urine specimens (9 isolates); fewer invasive isolates were collected and were obtained from ascites (1 isolate), the tip of a central venous catheter (CVC; 1 isolate), and drainage fluid (1 isolate). Twenty-four isolates were cultured from oral swab or sputum specimens from 10 HIV-infected patients during 2001 and 2002 (25). The information on each isolate is listed in Table 1. The identification of all isolates was done by a germ tube test, followed by testing with the VITEK2 yeast biochemical card and the API 32C system. The fungi were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates for 48 h at 37°C. The MICs of amphotericin B, fluconazole, and voriconazole for the C. glabrata isolates were determined by use of the guidelines presented in Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; formerly NCCLS) document M27-A (32).

TABLE 1.

Details of C. glabrata isolates tested by MLST, listed in order of their drug susceptibility testing results, and genotypes of the six DNA fragments sequenced

| Strain no. | HIV status | Source | MIC at 24 h/MIC at 48 h (mg/liter)

|

STa | MLST clonal group | PFGE type | Mating type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Amphotericin B | |||||||

| P01-1 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.125/1 | 7 | V2 | J1 | II |

| P01-2 | − | Anal swab | 0.125/4 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | 7 | V2 | J1 | II |

| P02-1 | − | Sputum | 8/32 | 0.25/1 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | G3 | II |

| P02-2 | − | Anal swab | 8/32 | 0.25/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 7 | V2 | G3 | II |

| P02-3 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | G4 | II |

| P03-1 | − | Sputum | 4/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | G2 | II |

| P03-2 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | G2 | II |

| P03-3 | − | Anal swab | 4/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | G2 | NDb |

| P04-1 | − | Sputum | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | L2 | I |

| P04-2 | − | Anal swab | 4/32 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | I1 | II |

| P04-3 | − | Ascites | 8/32 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.25/1 | 7 | V2 | I2 | II |

| P05-1 | − | Anal swab | 4/64 | 0.125/1 | 0.125/1 | 7 | V2 | G1 | II |

| P05-2 | − | Sputum | 4/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 7 | V2 | G1 | II |

| P05-3 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | M1 | I |

| P05-4 | − | Urine | 8/32 | 0.25/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | M1 | I |

| P06-1 | − | Anal swab | 0.125/128 | 0.03/8 | 0.125/0.25 | 7 | V2 | H3 | II |

| P06-2 | − | Throat swab | 2/4 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.125/0.25 | 7 | V2 | H1 | II |

| P06-3 | − | Anal swab | 8/8 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.125/0.5 | 7 | V2 | H2 | II |

| P07-1 | − | Sputum | 8/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.03/0.25 | N8 | V1 | K1 | II |

| P07-2 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.25/0.25 | N8 | V1 | K1 | II |

| P07-3 | − | Anal swab | ND | ND | ND | N8 | V1 | K2 | II |

| P08-1 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.25/1 | 0.25/1 | 26 | IV4 | A1 | II |

| P08-2 | − | Anal swab | 0.125/8 | 0.03/0.5 | 0.25/1 | N2 | I2 | I | |

| P08-3 | − | CVC | 2/4 | 0.125/1 | 0.25/1 | 26 | IV4 | A3 | II |

| P08-4 | − | Drainage fluid | 4/8 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 26 | IV4 | A4 | II |

| P09-1 | − | Anal swab | 4/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.25/1 | 15 | IV1 | P1 | II |

| P09-2 | − | Sputum | 4/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/1 | 15 | IV1 | P1 | II |

| P10-1 | − | Anal swab | 4/8 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 15 | IV1 | Q3 | II |

| P10-2 | − | Anal swab | 4/16 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 15 | IV1 | Q3 | II |

| P10-3 | − | Urine | 4/8 | 0.06/0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 15 | IV1 | Q3 | II |

| P11-1 | − | Anal swab | 16/128 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.25/1 | N1 | I1 | O3 | I |

| P11-2 | − | Sputum | 8/16 | 0.25/0.5 | 0.25/1 | 3 | VI1 | L1 | I |

| P11-3 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.125/1 | 3 | VI1 | L1 | I |

| P11-4 | − | Urine | 8/16 | 0.25/1 | 0.25/1 | 3 | VI1 | L1 | I |

| P12 | − | Urine | 2/8 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | N2 | I |

| P13-1 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | I | |

| P13-2 | − | Urine | 4/8 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.125/1 | N4 | II | ||

| P14-1 | − | Anal swab | 4/8 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.03/0.25 | 3 | VI1 | L3 | I |

| P14-2 | − | Urine | 4/16 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.03/0.25 | 3 | VI1 | L4 | I |

| P14-3 | − | Anal swab | 4/8 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.5/0.25 | 3 | VI1 | L3 | I |

| P15 | − | Stool | 0.125/8 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | N1 | I |

| P16-1 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.25/0.5 | 7 | V2 | K6 | II |

| P16-2 | − | Anal swab | 2/8 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.125/1 | N3 | I3 | I | |

| P17-1 | − | Urine | 0.125/4 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.25/1 | 15 | IV1 | Q1 | II |

| P17-2 | − | Anal swab | 4/16 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.25/1 | 15 | IV1 | Q2 | II |

| P18-1 | − | Anal swab | 8/16 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.125/0.25 | 7 | V2 | K4 | II |

| P18-2 | − | Urine | 4/16 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.125/0.5 | N9 | V3 | K5 | II |

| P19 | − | Anal swab | 4/8 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.125/0.5 | 26 | IV4 | A-2 | II |

| P20 | − | Sputum | 8/16 | 0.125/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 3 | VI1 | I | |

| P21 | − | Anal swab | 8/32 | 0.125/1 | 0.125/1 | N6 | III1 | E2 | II |

| P22 | − | Urine | 16/128 | 0.5/1 | 0.25/1 | N1 | I1 | O2 | I |

| P23 | − | Throat swab | 4/8 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.03/0.25 | 7 | V2 | K3 | II |

| P24 | − | Anal swab | 4/64 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.03/0.25 | N6 | III1 | F2 | II |

| P25 | − | Stool | ND | ND | ND | 26 | IV4 | B1 | II |

| P26 | − | Throat swab | 8/32 | 0.25/1 | 0.125/0.5 | 15 | IV1 | II | |

| P27 | − | Sputum | 4/8 | 0.06/0.25 | 0.125/0.5 | N7 | IV2 | P2 | II |

| P28-1 | + | Sputum | 2/32 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 26 | IV4 | B2 | II |

| P28-2 | + | Sputum | 2/16 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 26 | IV4 | B2 | II |

| P29-1 | + | Sputum | 2/16 | 0.125/ND | 0.5/0.5 | 7 | V2 | C3 | II |

| P29-2 | + | Sputum | 2/2 | 0.0325/ND | 0.5/1 | 7 | V2 | C2 | II |

| P30 | + | Sputum | 0.125/2 | 0.0325/ND | 0.5/0.5 | N10 | V4 | II | |

| P31-1 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.0325/ND | 0.5/1 | N6 | III1 | E1 | II |

| P31-2 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.125/ND | 0.5/1 | N6 | III1 | E1 | II |

| P32-1 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.0325/ND | 0.5/0.5 | N5 | II1 | S1 | I |

| P32-2 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.0325/ND | 1/1 | N5 | II1 | S1 | I |

| P32-3 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.065/ND | 1/1 | N5 | II1 | S1 | I |

| P33-1 | + | Oral cavity | 4/4 | 0.125/ND | 0.5/0.5 | 7 | V2 | D1 | I |

| P33-2 | + | Oral cavity | 4/4 | 0.25/ND | 0.5/0.5 | 7 | V2 | D1 | II |

| P34-1 | + | Oral cavity | 4/8 | 0.125/ND | 0.5/0.5 | N6 | III1 | F1 | II |

| P34-2 | + | Oral cavity | 0.125/0.25 | 0.5/ND | 1/1 | N6 | III1 | F1 | II |

| P34-3 | + | Oral cavity | 0.125/0.125 | 0.5/ND | 1/1 | N6 | III1 | F1 | II |

| P35-1 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | N1 | I1 | O1 | I |

| P35-2 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.25/ND | 1/1 | N1 | I1 | O1 | I |

| P35-3 | + | Oral cavity | 8/8 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | N1 | I1 | O1 | II |

| P36-1 | + | Oral cavity | 4/32 | 0.065/ND | 1/1 | 7 | V2 | C1 | II |

| P36-2 | + | Oral cavity | 4/32 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 7 | V2 | C1 | II |

| P36-3 | + | Oral cavity | 4/16 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 7 | V2 | C1 | II |

| P37-1 | + | Oral cavity | 4/16 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 10 | IV3 | R1 | I |

| P37-2 | + | Oral cavity | 4/32 | 0.125/ND | 0.5/1 | 10 | IV3 | R1 | I |

| P37-3 | + | Oral cavity | 4/16 | 0.125/ND | 1/1 | 10 | IV3 | R1 | I |

N1 to N10 are new STs.

ND, not determined.

DNA extraction.

The total genomic DNA of the strain was extracted by using the PUREGENE DNA purification kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN), as described previously (22). The concentration of DNA extracted from the C. glabrata isolates was measured with a spectrophotometer (A260). The DNA was stored at −20°C until use.

MLST.

MLST was based on six housekeeping genes, including the loci FKS, LEU2, NMT1, TRP1, UGP, and URA3 (16). PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 40 μl; and the mixtures contained 20 ng DNA, 0.4 μM each primer, and the mixture provided with the TEMPLY PCR kit (LTK BioLaboratories, Taipei, Taiwan). The reaction conditions were performed with an initial incubation at 94°C for 7 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, six different annealing temperatures for the six loci for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min (16). PCR was performed with a PTC-200 thermal cycler (MJ Research). DNA sequencing was performed by using the same primers used for the PCR, and both strands were sequenced.

Sequences and computations.

The sequences of both strands were aligned by the use of BioNumerics software (version 4.0; Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The sequences were compared with those in a central database, and the sequences and sequence type (ST) identifiers were obtained from http://cglabrata.mlst.net/. To compare the relationship of isolates from Taiwan with those from other countries, the MLST data for isolates from other countries were obtained from Dodgson et al. (17). The phylogenetic relationships among isolates were then assessed by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic means of the BioNumerics software. Assessment of the significance of the nodes was done by bootstrapping with 1,000 randomizations.

PFGE of BssHII restriction fragments.

Preparation of the plugs and restriction enzyme digestion were conducted as described previously (7). PFGE was performed with a Biometra Rotaphor apparatus with a pulse time of 3 to 15 s, at an angle of 120°, and at 180 V in a 0.8% agarose gel with 0.5× TBE (50 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 0.5 mM EDTA) for 40 h. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained in ethidium bromide solution for 20 min and destained in distilled water. The PFGE patterns were imaged with an IS-1000 digital imaging system (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA). The dendrograms were analyzed with BioNumerics software, as described previously (7). Isolates were assigned different PFGE genotypes when the band similarity value was less than 90%.

Mating type class identification.

A PCR-based approach was used to identify mating type classes I, II, and IV (39). Primer pair CGAR1 (5′-GAACTTGATTGGTGGTGATCCCA-3′) and AIRACE1 (5′-GAACTTGATTGGTGGTGATCCCA-3′) produced 300-bp products for classes I and II but not for class IV. Primer pair 12.36F1 (5′-ATGTCAGTCTGAACTAGTGAATA-3′) and PIRACE1 (5′-GCCATCAAGGTAGGTCTGAAT-3′) and primer pair PIRACE1 and CGP1R2 (5′-CTGAGAGAATGACGGAGAGTGTA-3′) generated 560-bp and 1.3-kb DNA product for classes II and IV, respectively, but not for class I. PCR was carried out with a total reaction mixture volume of 20 μl containing 40 ng of extracted DNA, 0.5 μl of each primer (10 μM), and the mixture from the TEMPLY PCR kit (LTK BioLaboratories). PCR was performed in a PTC-200 thermal cycler (MJ Research), with an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 min, 52°C for 30 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step of 72°C for 7 min.

Data and statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) by using cross tabs in the descriptive statistics to determine significant correlations based on Pearson's chi-square value of <0.05.

Calculation of discriminatory power.

The discriminatory index (DI) of each of the two typing methods was determined by the application of Simpson's index (26).

RESULTS

C. glabrata strain differentiation by MLST.

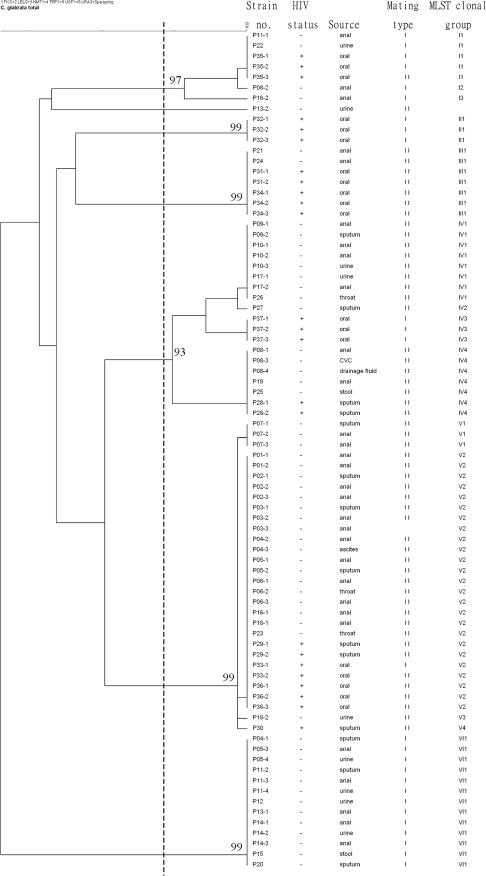

The six gene fragments sequenced allowed the differentiation of 15 multilocus STs among 80 isolates (Table 1). When the sequences were aligned with the sequences from the MLST Internet database for C. glabrata, 56 of the isolates belonged to STs 3, 7, 10, 15, and 26 (5, 17) and 24 isolates had novel STs (STs N1 to N10) (Fig. 1). The MLST dendrogram shows that all isolates except isolate P13-2 can be divided into six clonal groups (clonal groups I to VI) with values greater than 90% by bootstrap analysis and a sequence similarity threshold of 99.7%. Three major groups (groups IV, V, and VI) consisted of 78% of the isolates. Groups I, II, and III had novel STs, while groups IV, V, and VI had known STs and a few novel STs.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram indicating the similarities of the 80 C. glabrata isolates determined by MLST with six gene fragments. Groups were defined by a sequence similarity of 99.7% and bootstrap values of >90%.

A total of 3,345 bp from the six MLST loci (FKS, LEU2, NMT1, TRP1, UGP1, and URA3) was sequenced. Fifty-five (1.6%) nucleotide sites were found to be polymorphic. The number of polymorphisms per locus was 7 in the FKS locus, followed by 8 in LEU2, 14 in NMT1, 11 in TRP1, 5 in UGP1, and 10 in URA3; and the proportions of polymorphic sites per gene were as follows: 0.8% for UGP1, 1.2% for FKS, 1.6% for LEU2, 1.7% for URA3, 2.3% for NMT1, and 2.6% for TRP1. Sixteen (28.1%) of the 55 individual changes at variable sites were synonymous. The polymorphisms defined were three (UGP1), six (FKS), seven (LEU2), eight (URA3 and NMT1), and nine (TRP1) genotypes per locus. Among the six fragments, LEU2 gave the highest discriminatory ratio, yielding seven different genotypes from only eight polymorphic sites. Each of the six clonal groups corresponded to an NMT1 synaptomorphic allele, so the groups could be distinguished sufficiently by the use of NMT1, as described previously (16).

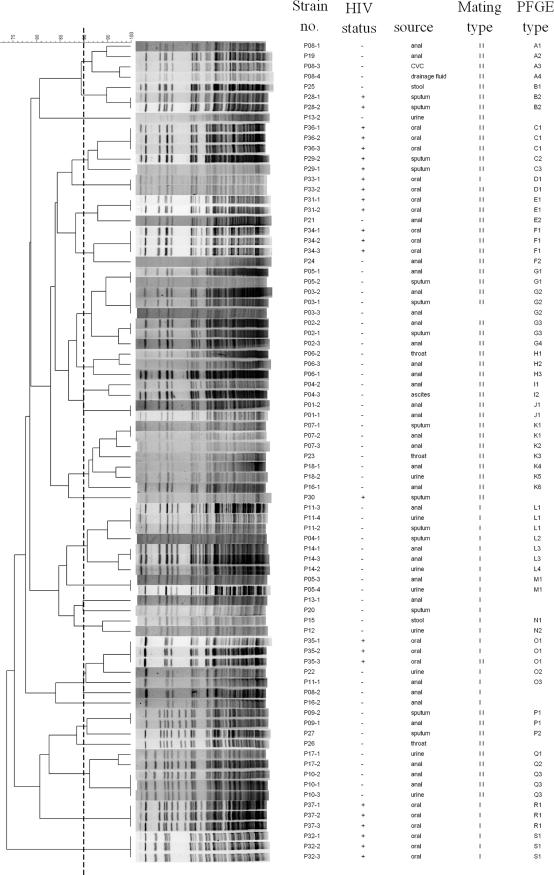

Comparison of typing abilities of MLST and PFGE.

MLST generated 15 STs (DI = 0.85), while PFGE with BssHII generated 54 DNA genotypes (DI = 0.99) (Table 1); hence, the former was much less discriminatory than the latter. MLST generated six clonal groups (clonal groups I to VI) with a similarity of 99.7%, and PFGE with BssHII generated 19 PFGE types (types A to S) with a similarity of 90% (Fig. 1).

Mating type class identification.

The mating type classes could be determined for 79 isolates. Fifty-three isolates (67%) were mating type II and belonged to MLST clonal groups III, IV, and V. Mating type I comprised 26 isolates (32%), which mainly belonged to clonal groups I, II, and VI.

Correlation among typing methods.

High correlations were found among the PFGE genotypes, the STs, and the mating types (P < 0.01).

Microevolution within an individual patient.

Among the 25 patients with multiple isolates, 19 patients contained multiple isolates of the same or highly related PFGE and MLST genotypes. Among them, four isolates from two HIV-infected patients (patients P33 and P35) demonstrated the same MLST and PFGE genotypes but were of different mating types for each patient, whereas for six patients (patients P04, P05, P08, P11, P13, and P16), multiple isolates from the same patient displayed distinctly different MLSTs, PFGE genotypes, or mating type classes (Table 1; Fig. 1 and 2).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram indicating the similarities of the 80 C. glabrata isolates determined by PFGE of fragments restricted with BssHII. Groups were defined by DNA pattern similarity of 90%.

Susceptibilities to fluconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B.

The MICs measured at 24 and 48 h for the 80 isolates are shown in Table 1. According to the criteria of the CLSI, at 48 h, 5% and 51% of the isolates were resistant (MICs ≥ 64 μg/ml) and susceptible dose dependent (16 μg/ml ≤ MICs ≤ 32 μg/ml) to fluconazole, respectively; 2% of the isolates were resistant to voriconazole (MICs ≥ 4 μg/ml); and all isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B (MICs ≤ 1 μg/ml). However, when trailing growth was considered (40), at 24 h, only 3% of the isolates were susceptible dose dependent to fluconazole, the others were susceptible to fluconazole, and all isolates were susceptible to voriconazole and amphotericin B.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirmed the usefulness of PFGE and MLST for the delineation of a set of prospectively collected, epidemiologically well defined isolates. Since the 1990s, Candida glabrata has become the second or third most common cause of candidemia in the United States, Canada, and Europe, as well as Taiwan (8, 31, 36). The increased prevalence of C. glabrata in the last decade may be attributed in part to its reduced susceptibility to the azole antifungals, such as fluconazole (35).

For epidemiology as well as phylogenetic studies, MLST allows not only the monitoring of variability within particular housekeeping genes due to evolutionary events but also the standardization of molecular typing information, which facilitates collaborative surveillance and comparison of the genotypes in a central database via the Internet. Few Asian C. glabrata isolates have been analyzed by MLST (16, 17), so we contributed the data for these Taiwanese isolates to reveal a global geographical relationship and epidemiology. MLST groups IV, V, and VI consisted of the STs found in Europe, the United States, and Japan, as well as new STs. MLST groups I, II, and III consisted entirely of new STs (STs N1 to N6) which were not found in other groups. The PFGE types of ST N1 to N6 isolates were also grouped independently.

When these isolates were analyzed for their drug susceptibilities, no correlation between reduced susceptibility and the MLST or the PFGE genotype was found, which is in concordance with the findings presented in previous reports (15, 16). No correlations were found between genotypes and clinical information, such as anatomic sources and hospital origin. In previous studies with C. albicans, mating types may be related to drug resistance (37, 41). In this study, no correlation between mating types and reduced susceptibility to amphotericin B and azole drugs was identified. No differences in drug susceptibility, genotype, or mating type distribution were identified between isolates from HIV-infected patients and those from non-HIV-infected patients.

Studies of C. albicans have shown that the same strain can persist for months to years, but few reports have pointed out that multiple strain types can coexist in individual patients (2, 14, 29). Among the 25 patients with multiple isolates, 19 patients (76%) contained multiple isolates that exhibited identical or highly related PFGE and MLST genotypes, which may imply that one strain of C. glabrata colonized each patient. Especially noteworthy is that two isolates from one HIV-infected patient (isolates P18-1 and P18-2) differed by only one polymorphic site (LEU2 498). Four isolates from two HIV-infected patients (patients P33 and P35) demonstrated the same MLST and PFGE genotypes, but the mating types of the isolates from each patient were different, which may provide evidence that a mating type switch occurred in the same strain at the colonized site as a result of microevolution (5). However, isolates from six patients (24%; patients P04, P05, P08, P11, P13, and P16) displayed different MLST genotypes, PFGE genotypes, or mating type classes, which may indicate colonization with more than one clone over time. This scenario suggested strain replacement (33). Two possibilities may explain the findings: first, multiple clones that colonized the patients underwent subsequent selection as a result of, for example, immunity, nutrient consumption, or medical treatment in vivo and resulted in the inhibition or proliferation of a specific strain; second, selections resulted in the subsequent eradication or reduction of the previously infecting strain, and reinfection with a new strain from another anatomical niche of the patient or the environment occurred. In addition, strains from anal swabs (nonsterile site) from patient P04 (strains P04-2 and P04-3) and strains from ascites, CVC, and drainage fluid (sterile sites) from patient P08 (strains P08-1, P08-3, and P08-4, respectively) had slight differences in PFGE patterns (Fig. 2). Previous studies with C. albicans strains also showed that one strain that transitioned from colonization of nonsterile sites to infection of sterile sites could be detected by changes in the short sequence repeat DNA fingerprinting patterns (1, 30). Such variation may imply microevolution, which resulted in a transition from colonization to invasion status. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the correlation of genomic differences and clinical characteristics.

Among the 80 isolates, 15 STs and 54 genotypes were identified by MLST and PFGE, respectively. MLST exhibited less discriminatory power than PFGE with BssHII. PFGE could efficiently further divide the groups defined by MLST. The C. glabrata MLST groups revealed a lower variable-site percentage of 1.6%, which is much less than that for C. albicans, and less discriminatory power was achieved. This may be due to the haploid nature of C. glabrata. High correlations were found among the PFGE genotypes, STs, and mating types (P < 0.01).

In conclusion, we have analyzed clinical isolates of C. glabrata using different delineation techniques and demonstrated that (i) in most patients, most isolates from an individual patient consisted of one colonizing strain, while for the other patients, the same or different anatomic sites may have been colonized with more than one strain; (ii) MLST showed that the population structure of C. glabrata in Taiwan consists of clonal groups closely related to those in other countries as well as some new clonal groups; (iii) for C. glabrata, the PFGE typing method is superior to MLST; and (iv) the genotypes, STs, or mating type classes were independent of anatomic sources, drug susceptibility, and HIV infection status.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DOH95-DC-2014 and DOH96-DC-2012 from the Center for Disease Control, Department of Health, Taiwan, and grant 96-0324-19-F-00-00-00-35 from the National Science Council of Taiwan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Aidan, A. W., W. Goessens, N. Lemmens-den Toom, M. Al Ahdal, and A. van Belkum. 2007. Microevolution in genomic short sequence repeats of Candida albicans in non-neutropenic patients. Yeast 24:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartie, K. L., D. W. Williams, M. J. Wilson, A. J. Potts, and M. A. Lewis. 2001. PCR fingerprinting of Candida albicans associated with chronic hyperplastic candidosis and other oral conditions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4066-4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bougnoux, M. E., S. Morand, and C. d'Enfert. 2002. Usefulness of multilocus sequence typing for characterization of clinical isolates of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1290-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bougnoux, M. E., A. Tavanti, C. Bouchier, N. A. Gow, A. Magnier, A. D. Davidson, M. C. Maiden, C. D'Enfert, and F. C. Odds. 2003. Collaborative consensus for optimized multilocus sequence typing of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5265-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brockert, P. J., S. A. Lachke, T. Srikantha, C. Pujol, R. Galask, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Phenotypic switching and mating type switching of Candida glabrata at sites of colonization. Infect. Immun. 71:7109-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, K. W., Y. C. Chen, H. J. Lo, F. C. Odds, T. H. Wang, C. Y. Lin, and S. Y. Li. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing for analyses of clonality of Candida albicans strains in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2172-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, K. W., H. J. Lo, Y. H. Lin, and S. Y. Li. 2005. Comparison of four molecular typing methods to assess genetic relatedness of Candida albicans clinical isolates in Taiwan. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Y. C., S. C. Chang, K. T. Luh, and W. C. Hsieh. 2003. Stable susceptibility of Candida blood isolates to fluconazole despite increasing use during the past 10 years. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Y. C., S. C. Chang, C. C. Sun, L. S. Yang, W. C. Hsieh, and K. T. Luh. 1997. Secular trends in the epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections at a teaching hospital in Taiwan, 1981 to 1993. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 18:369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, Y. C., S. C. Chang, H. M. Tai, P. R. Hsueh, and K. T. Luh. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of Candida colonizing critically ill patients in intensive care units. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 100:791-797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, Y. C., S. F. Lin, C. J. Liu, D. D. Jiang, P. C. Yang, and S. C. Chang. 2001. Risk factors for ICU mortality in critically ill patients. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 100:656-661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou, H. H., H. J. Lo, K. W. Chen, M. H. Liao, and S. Y. Li. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida tropicalis shows clonal cluster enriched in isolates with resistance or trailing growth of fluconazole. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Clark, T. A., and R. A. Hajjeh. 2002. Recent trends in the epidemiology of invasive mycoses. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 15:569-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross, L. J., D. W. Williams, C. P. Sweeney, M. S. Jackson, M. A. Lewis, and J. Bagg. 2004. Evaluation of the recurrence of denture stomatitis and Candida colonization in a small group of patients who received itraconazole. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 97:351-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Meeus, T., F. Renaud, E. Mouveroux, J. Reynes, G. Galeazzi, M. Mallie, and J. M. Bastide. 2002. Genetic structure of Candida glabrata populations in AIDS and non-AIDS patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2199-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodgson, A. R., C. Pujol, D. W. Denning, D. R. Soll, and A. J. Fox. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing of Candida glabrata reveals geographically enriched clades. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodgson, A. R., C. Pujol, M. A. Pfaller, D. W. Denning, and D. R. Soll. 2005. Evidence for recombination in Candida glabrata. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Espinel-Ingroff, A., J. A. Vazquez, D. Boikov, and M. A. Pfaller. 1999. Evaluation of DNA-based typing procedures for strain categorization of Candida spp. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33:231-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidel, P. L., Jr., J. A. Vazquez, and J. D. Sobel. 1999. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:80-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudlaugsson, O., S. Gillespie, K. Lee, B. J. Vande, J. Hu, S. Messer, L. Herwaldt, M. Pfaller, and D. Diekema. 2003. Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1172-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajjeh, R. A., A. N. Sofair, L. H. Harrison, G. M. Lyon, B. A. Arthington-Skaggs, S. A. Mirza, M. Phelan, J. Morgan, W. Lee-Yang, M. A. Ciblak, L. E. Benjamin, L. T. Sanza, S. Huie, S. F. Yeo, M. E. Brandt, and D. W. Warnock. 2004. Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1519-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu, M. C., K. W. Chen, H. J. Lo, Y. C. Chen, M. H. Liao, Y. H. Lin, and S. Y. Li. 2003. Species identification of medically important fungi by use of real-time LightCycler PCR. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:1071-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, Y. C., L. H. Su, T. L. Wu, and T. Y. Lin. 2004. Genotyping analysis of colonizing candidal isolates from very-low-birthweight infants in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 58:200-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung, C. C., Y. C. Chen, S. C. Chang, K. T. Luh, and W. C. Hsieh. 1996. Nosocomial candidemia in a university hospital in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 95:19-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung, C. C., Y. L. Yang, T. L. Lauderdale, L. C. McDonald, C. F. Hsiao, H. H. Cheng, Y. A. Ho, and H. J. Lo. 2005. Colonization of human immunodeficiency virus-infected outpatients in Taiwan with Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1600-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter, P. R., and C. A. Fraser. 1989. Application of a numerical index of discriminatory power to a comparison of four physiochemical typing methods for Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2156-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobsen, M. D., N. A. Gow, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, and F. C. Odds. 2007. Strain typing and determination of population structure of Candida krusei by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:317-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kao, A. S., M. E. Brandt, W. R. Pruitt, L. A. Conn, B. A. Perkins, D. S. Stephens, W. S. Baughman, A. L. Reingold, G. A. Rothrock, M. A. Pfaller, R. W. Pinner, and R. A. Hajjeh. 1999. The epidemiology of candidemia in two United States cities: results of a population-based active surveillance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1164-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, S. Y., Y. L. Yang, K. W. Chen, H. H. Cheng, C. S. Chiou, T. H. Wang, T. L. Lauderdale, C. C. Hung, and H. J. Lo. 2006. Molecular epidemiology of long-term colonization of Candida albicans strains from HIV-infected patients. Epidemiol. Infect. 134:265-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lunel, F. V., L. Licciardello, S. Stefani, H. A. Verbrugh, W. J. Melchers, J. F. Meis, S. Scherer, and A. van Belkum. 1998. Lack of consistent short sequence repeat polymorphisms in genetically homologous colonizing and invasive Candida albicans strains. J. Bacteriol. 180:3771-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malani, A., J. Hmoud, L. Chiu, P. L. Carver, A. Bielaczyc, and C. A. Kauffman. 2005. Candida glabrata fungemia: experience in a tertiary care center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:975-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts, approved standard. NCCLS document M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 33.Odds, F. C., A. D. Davidson, M. D. Jacobsen, A. Tavanti, J. A. Whyte, C. C. Kibbler, D. H. Ellis, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, and N. A. Gow. 2006. Candida albicans strain maintenance, replacement, and microvariation demonstrated by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3647-3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfaller, M. A. 1996. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging species, reservoirs, and modes of transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22(Suppl. 2):S89-S94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2004. Twelve years of fluconazole in clinical practice: global trends in species distribution and fluconazole susceptibility of bloodstream isolates of Candida. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10(Suppl. 1):11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, R. N. Jones, H. S. Sader, A. C. Fluit, R. J. Hollis, and S. A. Messer. 2001. International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibilities to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3254-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pujol, C., S. A. Messer, M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Drug resistance is not directly affected by mating type locus zygosity in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rustad, T. R., D. A. Stevens, M. A. Pfaller, and T. C. White. 2002. Homozygosity at the Candida albicans MTL locus associated with azole resistance. Microbiology 148:1061-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srikantha, T., S. A. Lachke, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Three mating type-like loci in Candida glabrata. Eukaryot. Cell 2:328-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takakura, S., N. Fujihara, T. Saito, T. Kudo, Y. Iinuma, and S. Ichiyama. 2004. National surveillance of species distribution in blood isolates of Candida species in Japan and their susceptibility to six antifungal agents including voriconazole and micafungin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavanti, A., A. D. Davidson, M. J. Fordyce, N. A. Gow, M. C. Maiden, and F. C. Odds. 2005. Population structure and properties of Candida albicans, as determined by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5601-5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavanti, A., A. D. Davidson, E. M. Johnson, M. C. Maiden, D. J. Shaw, N. A. Gow, and F. C. Odds. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing for differentiation of strains of Candida tropicalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5593-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wingard, J. R. 1995. Importance of Candida species other than C. albicans as pathogens in oncology patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wisplinghoff, H., T. Bischoff, S. M. Tallent, H. Seifert, R. P. Wenzel, and M. B. Edmond. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]