Abstract

Females are more susceptible than males to multiple sclerosis (MS). However, the underlying mechanism behind this gender difference is poorly understood. Because the presence of neuroantigen-primed T cells within the CNS is necessary for the development of MS, the present study was undertaken to investigate the activation of microglia by myelin basic protein (MBP)-primed T cells of male, female, and castrated male mice. Interestingly, MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and castrated male but not from male mice induced the expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) and proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-1α, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α) in microglia by cell-cell contact. Again there was no apparent defect in male microglia, because MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and castrated male but not male mice were capable of inducing the production of NO in male primary microglia. Inhibition of female T cell contact-mediated microglial expression of proinflammatory molecules by dominant-negative mutants of p65 and C/EBPβ suggest that female MBP-primed T cells induce microglial expression of proinflammatory molecules through the activation of NF-κB and C/EBPβ. Interestingly, MBP-primed T cells of male, female, and castrated male mice were able to induce microglial activation of NF-κB. However, MBP-primed T cells of female and castrated male but not male mice induced microglial activation of C/EBPβ. These studies suggest that microglial activation of C/EBPβ but not NF-κB by T cell:microglial contact is a gender-specific event and that male MBP-primed T cells are not capable of inducing microglial expression of proinflammatory molecules due to their inability to induce the activation of C/EBPβ in microglia. This novel gender-sensitive activation of microglia by neuroantigen-primed T cell contact could be one of the mechanisms behind the female-loving nature of MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS)2 is the most common human demyelinating disease of the CNS. It has been known for decades that females are twice as likely as males to be affected from MS (1-3). About 66% of all MS patients are female (2, 3). This gender bias is also consistent with many other autoimmune diseases, including Addison, rheumatoid arthritis, pernicious anemia, Sjogren, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroiditis, in which women are also preferentially affected (2). Consistently animal models of different autoimmune disease such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in SJL mice, thyroiditis, adjuvant arthritis, Sjogren syndrome in MRL/lpr mice, diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice, and spontaneous systemic lupus erythematosus in NZBx-NZW mice also exhibit bias to females (4-7). Despite extensive research, the molecular mechanism behind this female prevalence is poorly understood.

The hallmark of brain inflammation in MS is the activation of glial cells, especially that of microglia that express and produce a variety of proinflammatory and neurotoxic molecules, including inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) and proinflammatory cytokines (8, 9). Semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR for iNOS mRNA in MS brains shows markedly higher expression of iNOS mRNA in MS brains than in normal brains (10, 11). According to Bagsra et al. (11), the mRNA for iNOS was detectable in all the brains examined from patients with MS and EAE but none of the control brains. Inhibition of iNOS in both rat and mouse model of EAE by aminoguanidine also prevented the clinical development of EAE (12). Subsequently, Hooper et al. (13, 14) have reported that uric acid, a scavenger of peroxynitrite (a highly reactive derivative of NO), markedly inhibits the appearance of EAE in mice, and that the incidence of MS is very rare among gout patients having higher levels of uric acid. Among proinflammatory cytokines, primary inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β/α, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α/β, and IL-6, play a predominant role, because they are involved at multiple levels of neuroimmune regulation (9, 15, 16). Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid from MS patients has shown increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines compared with normal control, and levels of those cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients also correlate with disease severity (9, 17, 18). Consistently, blockade of proinflammatory cytokine synthesis or function by signaling inhibitors or neutralizing antibodies or gene knock-out can also prevent the development of EAE (19-21).

Recently we have observed that neuroantigen-specific T cells induce specifically microglial expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) through cell-cell contact (22, 23). Because neuroantigen-specific T cells play a key role in the pathogenesis of MS, to understand the molecular basis of gender difference in MS, we investigated the effect of MBP-primed T cells isolated from female, male, and castrated male mice on contact-mediated activation of microglia. Here we demonstrate that MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and castrated male but not male mice induced the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) in microglia by cell-cell contact. Furthermore, we show that MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and castrated male but not male mice were capable of inducing proinflammatory molecules in both male and female microglia suggesting a possible defect in male T cells but not in microglia. Consistent with the involvement of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in the expression of microglial proinflammatory molecules (23, 24), MBP-primed T cells of female and castrated male mice induced the activation of both NF-κB and C/EBPβ in microglia by cell-cell contact. In contrast, male MBP-primed T cells induced microglial activation of only NF-κB but not C/EBPβ. These results suggest that male MBP-primed T cells are not capable of activating microglia due to their inability to induce the activation of C/EBPβ in microglia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Fetal bovine serum, Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), DMEM/F-12, RPMI 1640, L-glutamine, and β-mercaptoethanol were from Mediatech. Assay systems for IL-1β and TNF-α were purchased from BD Pharmingen. Bovine myelin basic protein was purchased from Invitrogen. [α-32P]dCTP and [γ-32P]ATP were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The dominant-negative mutant of C/EBPβ (ΔC/EBPβ) was kindly provided by Dr. Steve Smale of the University of California at Los Angeles.

Isolation and Purification of Antigen-primed T Cells

Specific pathogen-free female, male, and castrated male SJL/J mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Inc. MBP-primed T cells were isolated and purified as described earlier (22, 23). Briefly, mice were immunized subcutaneously with 400 μg of bovine MBP and 60 μg Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37RA, Difco Laboratoies) in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (Calbiochem). Lymph nodes were collected from these mice, and single cell suspension was prepared in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured at a concentration of 4–5 × 106 cells/ml in six-well plates. Cells isolated from MBP-immunized mice were incubated with 50 μg/ml MBP for 4 days. The non-adherent cells were collected, and T cells were purified through a nylon wool column (22). Viability and purity of the cells were checked by trypan blue exclusion and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, respectively. About 98% of the cells were found as CD3-positive T cells (22). These T cell populations were used to stimulate microglial cells.

Isolation of Mouse Primary Microglia

Microglial cells were isolated from mixed glial cultures according to the procedure of Guilian and Baker (25). Briefly, on days 7–9 the mixed glial cultures were washed three times with DMEM/F-12 and subjected to a shake at 240 rpm for 2 h at 37 °C on a rotary shaker. The floating cells were washed and seeded onto plastic tissue culture flasks and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The attached cells were removed by trypsinization and seeded onto new plates for further studies. 90–95% of this preparation was found to be positive for Mac-1 surface antigen. For the induction of TNF-α production, cells were stimulated with MBP-primed T cells in serum-free DMEM/F-12. Mouse BV-2 microglial cells (kind gift from Virginia Bocchini of University of Perugia) were also maintained and induced with different stimuli as indicated above.

Stimulation of Mouse BV-2 Microglial Cells and Primary Microglia by MBP-primed T Cells

Microglial cells were stimulated with different concentrations of MBP-primed T cells under serum-free condition. After 1 h of incubation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower the concentration of T cells. Earlier, by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of adherent microglial cells using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD3 antibodies, we demonstrated that more than 80% T cells were removed from microglial cells by this procedure (23). Then microglial cells were incubated in serum-free media for different periods of time depending on experiments.

Assay for NO Synthesis

Synthesis of NO was determined by assay of culture supernatants for nitrite, a stable reaction product of NO with molecular oxygen. Briefly, supernatants were centrifuged to remove cells, and 400 μl of each supernatant was allowed to react with 200 μl of Griess reagent (26, 27) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The optical density of the assay samples was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. Fresh culture media served as the blank. Nitrite concentrations were calculated from a standard curve derived from the reaction of NaNO2 in the assay.

Immunoblot Analysis for iNOS

Immunoblot analysis for iNOS was carried out as described earlier (26, 27). Briefly, cells were detached by scraping, washed with Hank’s buffer, and homogenized in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin). After electrophoresis the proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and the iNOS band was visualized by immunoblotting with antibodies against mouse macrophage iNOS and 125I-labeled protein A (26, 27).

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis

Cells were taken out of the culture dishes directly by adding Ultraspec-II RNA reagent (Biotecx Laboratories, Inc.), and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For Northern blot analyses, 20 μg of total RNA was electrophoresed on 1.2% denaturing formaldehyde-agarose gels, electrotransferred to Hybond nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and hybridized at 68 °C with 32P-labeled cDNA probe using Express Hyb hybridization solution (Clontech) as described by the manufacturer. The cDNA probe was made by polymerase chain reaction amplification using two primers (forward primer: 5′-CTC CTT CAA AGA GGC AAA AAT A-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CAC TTC CTC CAG GAT GTT GT-3′) (26, 27). After hybridization, the filters were washed two or three times in solution I (2 × SSC, 0.05% SDS) for 1 h at room temperature followed by solution II (0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 50 °C for another hour. The membranes were then dried and exposed to x-ray films (Kodak). The same amount of RNA was hybridized with probe for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Assay for IL-1β and TNF-α Synthesis

Concentrations of IL-1β and TNF-α were measured in culture supernatants by a high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction as described earlier (23, 28). Protein was measured by the procedure of Bradford (29).

RNA Isolation and Analysis of Different Proinflammatory and Anti-inflammatory Cytokines by Gene Array

BV-2 microglial cells were stimulated with MBP-primed T cells (0.5:1 of T cell:microglia), and after 1 h of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower T cell concentration. Then BV-2 cells received serum-free media, and after 3 h of incubation, expression of different proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines was analyzed in adherent BV-2 cells by a gene array kit (GEArray™) from SuperArray, Inc. following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from stimulated or unstimulated BV-2 microglial cells by using Ultraspec-II RNA reagent (Biotecx Laboratories Inc.). This RNA was used as a template for [32P]cDNA probe synthesis using [α-32P]dCTP and Moloney Murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. The GEArray membrane was prehybridized, hybridized with [32P]cDNA probe, and washed two or three times in solution I (2 × SSC, 0.05% SDS) for 1 h at room temperature followed by solution II (0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 50 °C for another hour. The membranes were then dried and exposed to x-ray films (Kodak).

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts and Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

After different minutes of stimulation of BV-2 microglial cells by MBP-primed T cells, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower T cell concentration. Then nuclear extracts were prepared from adherent BV-2 cells using the method of Dignam et al. (30) with slight modifications. Cells were harvested, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in 400 μl of buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin) containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40 for 15 min on ice, vortexed vigorously for 15 s, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 s. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 40 μl of buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 25% (v/v) glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin). After 30 min on ice, lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Supernatants containing the nuclear proteins were diluted with 20 μl of modified buffer C (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.05 M KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mM PMSF) and stored at 70 °C until use. Nuclear extracts were used for electrophoretic mobility shift assay using 32P end-labeled double-stranded (NF-kB, 5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′ (Promega) and C/EBPβ, 5′-TGC AGA TTG CGC AAT CTG CA-3′ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.)) oligonucleotides. Double-stranded mutated (NF-κB, 5′-AGT TGA GGC GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′, and C/EBPβ, 5′-TGC AGA GAC TAG TCT CTG CA-3′ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.)) oligonucleotides were used to verify the specificity of NF-κB and C/EBPβ binding to DNA.

Assay of Transcriptional Activities of NF-κB and C/EBPβ

To assay the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and C/EBPβ, cells at 50–60% confluence in 12-well plates were transfected with 0.5 μg of either PBIIX-Luc, an NF-κB-dependent reporter construct (26), or pC/EBPβ-Luc, an C/EBPβ-dependent reporter construct (26), using the Lipofectamine Plus method (Invitrogen) (23, 26, 31). All transfections included 50 ng/μg total DNA of pRL-TK (a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase, used as transfection efficiency control, Promega). After 24 h of transfection, cells were stimulated with MBP-primed T cells (0.5:1 of T cell: microglia). After 1 h of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower T cell concentration. Then BV-2 cells were incubated with serum-free media for 5 h. Adherent BV-2 cells were analyzed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities according to standard instructions provided in the Dual Luciferase Kit (Promega) in a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs). Relative luciferase activity of cell extracts was typically represented as (firefly luciferase value/Renilla luciferase value) × 10−3.

RESULTS

MBP-primed T Cells Isolated from Female but Not Male SJL/J Mice Induced the Expression of iNOS in BV-2 Microglial Cells

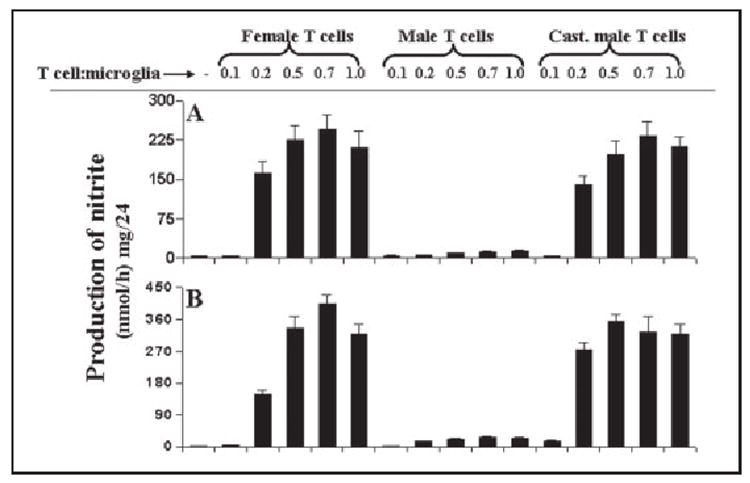

Earlier we have observed that MBP-primed T cells from female SJL/J mice induce the expression of iNOS in microglia by cell-cell contact (22) suggesting that neuroantigen-primed T cell contact-mediated microglial expression of iNOS may participate in the pathogenesis of MS. As females are more susceptible to MS than males, to understand the molecular basis of gender difference in MS, we investigated the effect of MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and male SJL/J mice on contact-mediated expression of iNOS in microglia. T cells isolated from MBP-immunized female and male SJL/J mice proliferated in response to MBP, and the maximum proliferation was observed at 50 or 100 μg/ml of MBP (data not shown). Therefore, these cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml MBP, and after nylon-wool column purification, MBP-primed T cells were washed and added to BV-2 microglial cells in direct contact (22, 23). After 1 h of contact, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice to remove MBP-primed T cells. In an earlier study (23), we observed, by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of adherent microglial cells using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD3 antibodies, that >80% T cells were removed from microglial cells by this procedure. As observed earlier (22), female MBP-primed T cells markedly induced the production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells (Fig. 1A). The induction of NO production started from the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cell:microglia, reached to the maximum at the ratio of 0.7:1, and decreased at higher concentrations of T cells (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, MBP-primed T cells from male SJL/J mice were unable to induce the production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells under same condition (Fig. 1A) suggesting the possible involvement of male sex hormone in disabling male MBP-primed T cells from contact-mediated activation of microglia. To further confirm this hypothesis, we isolated MBP-primed T cells from castrated male mice. Similar to female MBP-primed T cells, MBP-primed T cells from castrated male SJL/J mice induced the production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells exhibiting the maximum NO production at the ratio of 0.7:1 of T cell:glia (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1. MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice induce the production of nitrite in mouse BV-2 microglial cells and primary microglia.

BV-2 cells (A) and primary microglia (B) received different concentrations of MBP-primed T cells of female, male, and castrated male mice in direct contact under serum-free condition. After 1 h of incubation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to remove the burden of T cells. Then adherent microglial cells were incubated in serum-free media for 23 h, and supernatants were used to assay nitrite as mentioned under “Materials and Methods.” Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

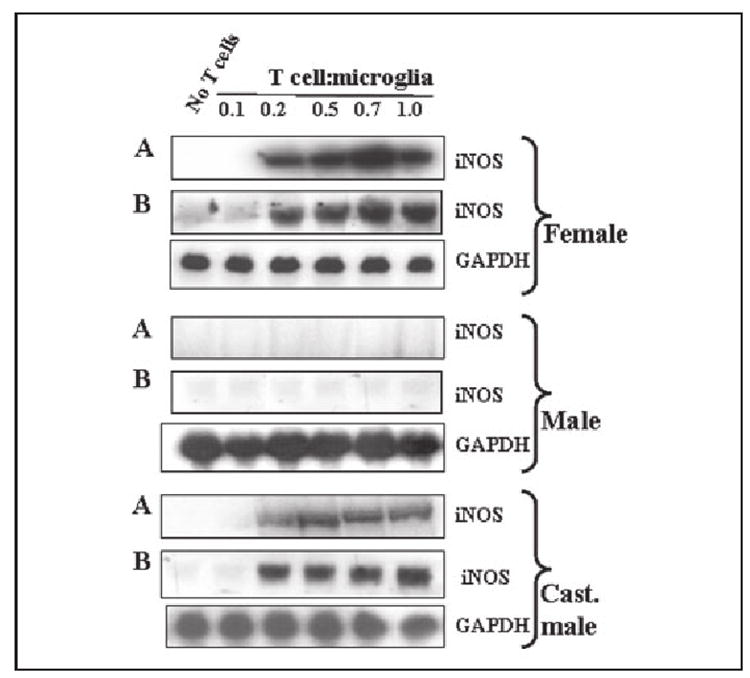

To understand further the mechanism of NO production, we examined the effect of male, female, and castrated male MBP-primed T cells on protein and mRNA levels of iNOS. Western blot analysis with antibodies against murine macrophage iNOS and Northern blot analysis for iNOS mRNA clearly showed that MBP-primed T cells of female and castrated male were capable of inducing the expression of iNOS protein (Fig. 2A) and iNOS mRNA (Fig. 2B). Consistent to the induction of NO production, MBP-primed T cells did not induce the expression of iNOS protein and mRNA in BV-2 microglial cells when added at a ratio of 0.1:1. The induction of iNOS protein and mRNA by female and castrated male MBP-primed T cells started at the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cell: microglia and peaked at the ratio of 0.7:1 (Fig. 2). However, under the same condition, male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the expression of iNOS protein and mRNA at different concentrations of T cell:microglia (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice induce the expression of iNOS in mouse BV-2 microglial cells.

BV-2 cells received different concentrations of MBP-primed T cells of female, male, and castrated male mice in direct contact under serum-free condition. After 1 h of incubation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to remove the burden of T cells. A, then adherent BV-2 cells were incubated in serum-free media for 23 h. Cell homogenates were electrophoresed, transferred on nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with antibodies against mouse macrophage iNOS as mentioned under “Materials and Methods.” B, after removal of T cells, adherent BV-2 cells were incubated in serum-free media for 5 h, and Northern blot analysis for iNOS mRNA was carried out as described under “Materials and Methods.”

MBP-primed T Cells Isolated from Female and Castrated Male but Not Male SJL/J Mice Induced the Production of NO in Mouse Primary Microglia

To understand if MBP-primed T cells isolated from female and castrated male but not male mice also induced the production of NO in primary cells, we examined the effect of these T cells on the production of NO in mouse primary microglia. Consistent with the induction of NO in BV-2 microglial cells, MBP-primed T cells of female and castrated male mice dose-dependently induced the production of NO in mouse primary microglia (Fig. 1B). Similar to in BV-2 cells, MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the production of NO in primary microglia when added at a ratio of 0.1:1 of T cells and microglia (Fig. 1B). However, the induction of NO production started from the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cell:microglia and reached to the maximum at the ratio of 0.5:1 or 0.7:1 (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, male MBP-primed T cells at different ratios of T cell:microglia did not induce the production of NO in primary microglia (Fig. 1B).

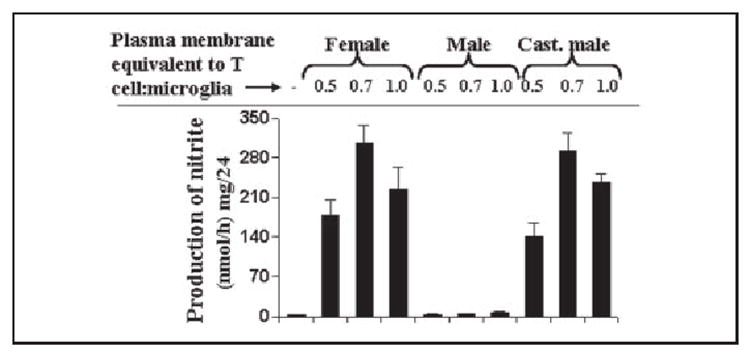

Are Plasma Membranes of MBP-primed T Cells Capable of Inducing the Production of NO in BV-2 Microglial Cells?

Although we were able to remove >80% of T cells from microglia by shaking culture dishes (23), the remaining MBP-primed T cells may in fact produce soluble mediators to influence microglial induction of NO production. Therefore, to further confirm that the contact of MBP-primed T cells to microglia is in fact responsible for gender-specific activation of microglia, we investigated the effect of plasma membranes of MBP-primed T cells on the production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells. Consistent to the effect of intact MBP-primed T cells on BV-2 microglial cells, plasma membranes of female as well as castrated male MBP-primed T cells markedly induced the production of NO (Fig. 3). On the other hand, plasma membranes of male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells (Fig. 3) suggesting that male MBP-primed T cells are defective in inducing the production of NO in microglia by cell-cell contact.

FIGURE 3. Plasma membranes of MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice induce the production of nitrite in mouse BV-2 microglial cells.

After counting, MBP-primed T cells were subjected to plasma membrane preparation as mentioned under “Materials and Methods.” BV-2 cells were incubated with plasma membranes of MBP-primed T cells isolated from female, male, and castrated male mice under serum-free condition. After 24 h of incubation, supernatants were used to assay nitrite. Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

Is There Any Defect in Male Microglia?

Because male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the production of NO in mouse BV-2 microglial cells and primary microglia (Fig. 1), and the expression of iNOS mRNA in the CNS of male EAE was much less compared with that of female EAE (32), we investigated if male microglia were defective in the induction of NO production in response to MBP-primed T cells. Primary microglia isolated from male and female SJL/J mice were stimulated by MBP-primed T cells from male, female, and castrated male mice as described above. Interestingly, MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male SJL/J mice were found to induce the production of NO in primary microglia isolated from male as well as female SJL/J mice (TABLE ONE). On the other hand, MBP-primed T cells from male SJL/J mice were unable to induce NO production in microglia isolated from either female or male mice (TABLE ONE). These observations suggest that there is no defect in male microglia with respect to the contact-mediated induction of NO production, and the defect lays specifically in male MBP-primed T cells that are unable to induce contact-mediated production of NO in microglia.

TABLE ONE. Induction of NO production in male and female microglia by female, male, and castrated male MBP-primed T cells.

Male and female primary microglia were stimulated by MBP-primed T cells at different ratios of T cells:microglia in serum-free DMEM/F-12. After 1 h of incubation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to remove the burden of T cells. Then adherent microglia were incubated in serum-free media for 23 h, and supernatants were used to assay nitrite as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments

| Treatment by

MBP-primed T cells |

T cell: microglia | Production of nitrite | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male microglia | Female microglia | ||

| nmol/mg/24 h | |||

| No stimulation | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | |

| Female | 0.5:1 | 310 ± 35 | 350 ± 52 |

| 0.7:1 | 405 ± 42 | 375 ± 63 | |

| 1:1 | 325 ± 54 | 309 ± 32 | |

| Male | 0.5:1 | 32 ± 5.2 | 21 ± 2.6 |

| 0.7:1 | 36 ± 3.6 | 34 ± 4.3 | |

| 1:1 | 38 ± 4.8 | 41 ± 3.6 | |

| Castrated male | 0.5:1 | 335 ± 36 | 275 ± 31 |

| 0.7:1 | 355 ± 28 | 395 ± 51 | |

| 1:1 | 326 ± 22.5 | 320 ± 45 | |

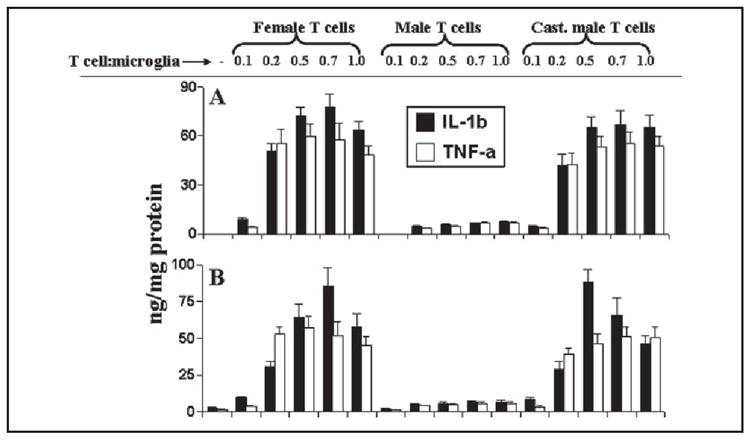

MBP-primed T Cells Isolated from Female and Castrated Male but Not Male Mice Induced the Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines in Mouse BV-2 Microglial Cells and Primary Microglia

Earlier we have observed that, similar to microglial induction of NO production, female MBP-primed T cells are also capable of inducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines in microglia (23). Because MBP-primed T cell contact-induced microglial production of NO is gender-sensitive (Figs. 1-3), we investigated if T cell contact-mediated induction of microglial proinflammatory cytokines was also a gender-sensitive event. There was also very little or no induction of IL-1β and TNF-α production when any of the three types of MBP-primed T cells were added to BV-2 microglial cells at a ratio of 0.1:1 (Fig. 4A). However, female MBP-primed T cells markedly induced the production of IL-1β and TNF-α in BV-2 microglial cells at different ratios of T cell:microglia with the maximum induction observed at a ratio of 0.5:1 or 0.7:1 T cell:microglia (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the production of IL-1β and TNF-α in BV-2 microglial cells at different ratios of T cell:microglia (Fig. 4A). However, similar to female MBP-primed T cells, MBP-primed T cells of castrated male mice also markedly induced the production of IL-1β and TNF-α in BV-2 microglial cells at different ratios of T cell:microglia (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the induction of IL-1β and TNF-α production in BV-2 microglial cells, MBP-primed T cells of female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice also induced the production of IL-1β and TNF-α in mouse primary microglia at different ratios of T cell:glia (Fig. 4B). These observations suggest that, similar to the induction of NO production, microglial production of proinflammatory cytokines by MBP-primed T cell contact is also gender-sensitive.

FIGURE 4. MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines in mouse BV-2 microglial cells and primary microglia.

BV-2 cells (A) and primary microglia (B) received different concentrations of MBP-primed T cells of female, male, and castrated male mice in direct contact under serum-free condition. After 1 h of incubation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to remove the burden of T cells. Then adherent microglial cells were incubated in serum-free media for 23 h, and supernatants were used to assay IL-1β and TNF-α as mentioned under “Materials and Methods.” Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

Effect of Female and Male MBP-primed T Cells on the Expression of Different Cytokines in BV-2 Microglial Cells

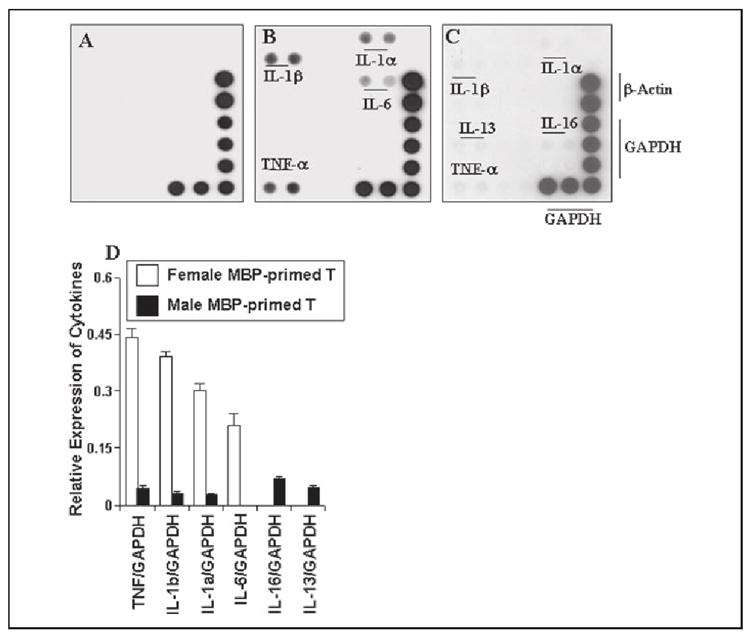

To understand further the mechanism of gender-specific microglial induction of IL-1β and TNF-α production by MBP-primed T cells, we examined the effect of female and male MBP-primed T cells on the expression of different cytokines in BV-2 microglial cells by cytokine gene array analysis using the GEArray kit from SuperArray Inc. After 1 h of stimulation of BV-2 microglial cells by MBP-primed T cells, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to remove any extra or loosely-bound T cells. Following 3 h of incubation in serum-free media, total RNA was isolated from adherent BV-2 microglial cells to perform gene array analysis. This gene array analysis allowed us to study the expression of 23 different proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interferon-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12 p35, IL-12p40, IL-13, IL-15, IL-16, IL-17, IL-18, lymphotoxin-b, TNF-α, and TNF-β. Normal T cells were unable to induce any of these cytokines in BV-2 microglial cells (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, female MBP-primed T cells in the ratio of 0.5:1 of T cell:microglia strongly induced contact-mediated expression of IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6 (Fig. 5, B and D), proinflammatory cytokines that are involved in the pathogenesis of MS (6, 9, 13). However, under the same condition, male MBP-primed T cells induced the expression of IL-1β, IL-1α, and TNF-α very weakly (Fig. 5, C and D). In contrast to female MBP-primed T cell-stimulated microglia, the expression of IL-6 was not detected in male MBP-primed T cell-induced microglial cells (Fig. 5). On the other hand, male MBP-primed T cells induced weak microglial expression of IL-16 and IL-13, the cytokines that were not induced by female MBP-primed T cells (Fig. 5, C and D). These results suggest MBP-primed T cell contact-induced microglial expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) is also gender-sensitive.

FIGURE 5. MBP-primed T cells induce the expression of different proinflammatory cytokines in mouse BV-2 microglial cells.

BV-2 cells were stimulated with normal (A), female (B), or male MBP-primed T cells (C) (0.5:1 of T cell:glia) under serum-free condition. After 1 h of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower T cell concentration. Then BV-2 cells received serum-free media, and after 3 h of incubation, total RNA was isolated from adherent BV-2 cells for the analysis of different proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines by a gene array kit (GEArray™) from SuperArray, Inc. following the manufacturer’s protocol. D, the relative expression of different cytokines (cytokines/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was measured after scanning the bands with a Fluor Chem 8800 Imaging System (Alpha Innotech Corp.). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

MBP-primed T Cells Induce the Activation of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in BV-2 Microglial Cells

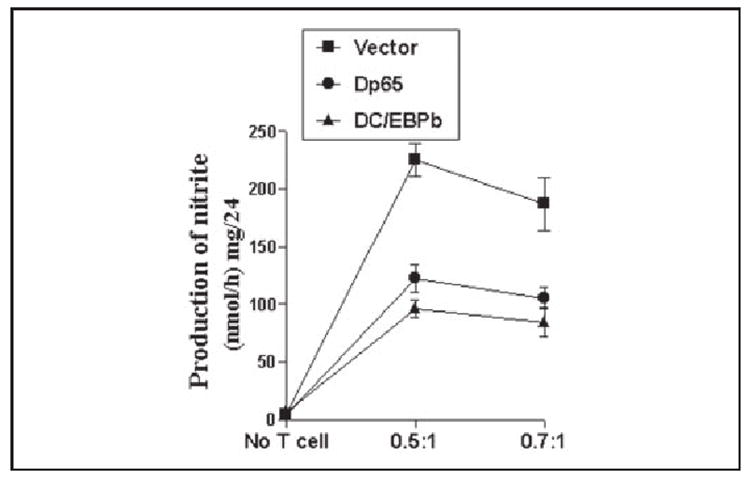

It has been shown that activation of both NF-κB and C/EBPβ are involved in the expression of different proinflammatory molecules in monocytes and macrophages following inflammatory insult (33-35). Earlier we have also shown that female MBP-primed T cells induce the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in microglia through the activation of NF-κB and C/EBPβ (23). Here we examined if activation of both NF-κB and C/EBPβ is important for female MBP-primed T cell-induced microglial production of NO. Overexpression of dominant-negative molecules provides an effective tool with which to investigate the in vivo functions of different transcription factors or signaling molecules. Therefore, microglial NF-κB and C/EBPβ were inhibited by respective dominant-negative mutants as described earlier (23, 26). It is apparent from Fig. 6 that expression of Δp65 and ΔC/EBPβ but not that of the empty vector inhibited female MBP-primed T cell-induced production of NO in BV-2 microglial cells.

FIGURE 6. Dominant-negative mutants of p65 (Δp65) and C/EBPβ(ΔC/EBPβ) inhibit female MBP-primed T cell-induced production of nitrite in BV-2 microglial cells.

Cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of either Δp65 or ΔC/EBPβ using Lipofectamine Plus. After 24 h of transfection, cells were stimulated with female MBP-primed T cells under serum-free condition. After 1 h of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS to lower T cell concentration. Then adherent BV-2 cells were incubated in serum-free media for another 23 h, and supernatants were used to assay nitrite. Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

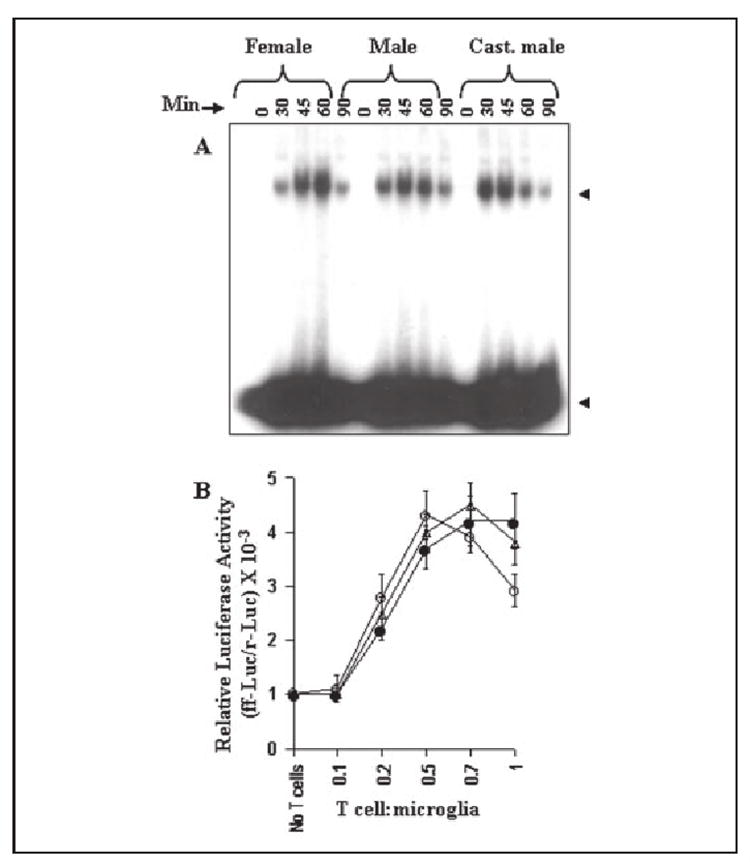

Therefore, we were prompted to investigate if similar to female MBP-primed T cells, male, and castrated male MBP-primed T cells were also capable of inducing the activation of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in BV-2 microglial cells. Activation of NF-κB was monitored by both DNA-binding and transcriptional activities. DNA-binding activity of NF-κB was evaluated by the formation of a distinct and specific complex in a gel shift DNA binding assay. Treatment of BV-2 glial cells with female MBP-primed T cells at a ratio of 0.5:1 of T cell:glia resulted in the induction of DNA-binding activity of NF-κB at different minutes of stimulation (Fig. 7A). This gel shift assay detected a specific band in response to MBP-primed T cells that was not found in the case of mutated double-stranded oligonucleotides (data not shown) suggesting that female MBP-primed T cell-microglia contact induces the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB. This was further verified by NF-κB-dependent transcription of luciferase in BV-2 microglial cells, using the expression of luciferase from a reporter construct, PBIIX-Luc, as an assay. Female MBP-primed T cells did not induce the activation of NF-κB in BV-2 microglial cells when added at a ratio of 0.1:1. However, the activation of NF-κB started at the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cell:microglia and peaked at the ratio of 0.5:1 (Fig. 7B). Similarly, male and castrated male MBP-primed T cells also induced DNA binding as well as transcriptional activity of NF-κB in BV-2 microglial cells (Fig. 7, A and B) suggesting that microglial activation of NF-κB by MBP-primed T cell contact is not gender-sensitive.

FIGURE 7. MBP-primed T cells from female, male, and castrated male SJL/J mice induce the activation of NF-κB in BV-2 microglial cells.

A, cells incubated in serum-free DMEM/F-12 were stimulated with female, male, and castrated male MBP-primed T cells (0.5:1 of T cell:glia). After different minutes of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS. Adherent cells were taken out to prepare nuclear extracts, and nuclear proteins were used for electrophoretic mobility shift assay as described under “Materials and Methods.” The upper and lower arrows indicate the induced NF-κB band and the unbound probe, respectively. B, cells plated at 50–60% confluence in 12-well plates were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of PBIIX-Luc and 25 ng of pRL-TK using Lipofectamine Plus as described under “Materials and Methods.” After 24 h of transfection, BV-2 cells were stimulated with different concentrations of female (○), male (●), and castrated male (Δ) MBP-primed T cells. After 1 h of stimulation, T cells were removed followed by the incubation of adherent BV-2 cells in serum-free media for another 5 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were obtained by analyzing total cell extract of BV-2 cells as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

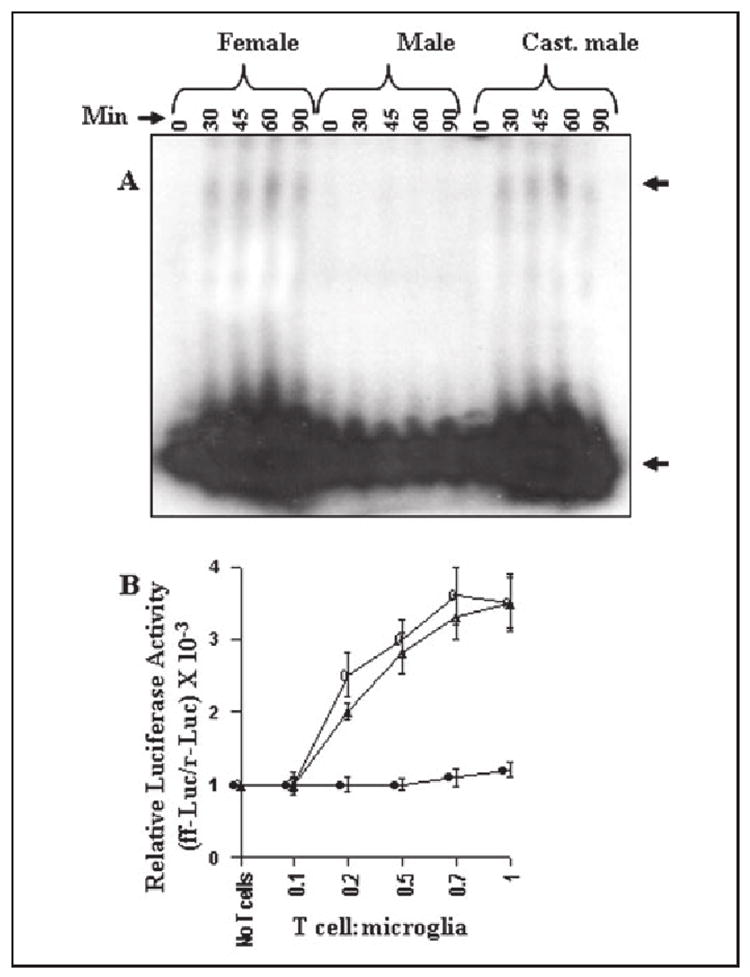

Next we investigated DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of C/EBPβ. Similar to the activation of NF-κB, female MBP-primed T cells also induced the DNA-binding activity of C/EBPβ in different minutes of stimulation (Fig. 8A). The specific band in response to female MBP-primed T cells was observed only in the case of the double-stranded wild type oligonucleotides but not in the case of the mutated ones (data not shown). It is also evident from the C/EBPβ-dependent luciferase assay in Fig. 8B that female MBP-primed T cells markedly induced the transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ. Similar to the activation of NF-κB, there was no activation of C/EBPβ in BV-2 microglial cells when female MBP-primed T cells were added at a ratio of 0.1:1. However, the activation of C/EBPβ started at the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cell:microglia and peaked at the ratio of 0.7:1 (Fig. 8B). Also, in contrast to female MBP-primed T cells, male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce both DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of C/EBPβ in BV-2 microglial cells at different ratios of T cell:glia (Fig. 8, A and B) suggesting that male sex hormone probably disables male MBP-primed T cells from contact-mediated activation of C/EBPβ in microglia. Consistently, after castration of male mice, MBP-primed T cells restored this contact activity. As observed in Fig. 8, similar to female MBP-primed T cells, castrated male MBP-primed T cells induced DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of C/EBPβ. Taken together, these results suggest that microglial activation of C/EBPβ but not NF-κB by T cell:microglial contact is a gender-specific event and that male MBP-primed T cells are not capable of inducing microglial expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines due to their inability to induce the activation of C/EBPβ in microglia.

FIGURE 8. MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male but not male SJL/J mice induce the activation of C/EBPβ in BV-2 microglial cells.

A, cells incubated in serum-free DMEM/F-12 were stimulated with female, male, and castrated male MBP-primed T cells (0.5:1 of T cell:glia). After different minutes of stimulation, culture dishes were shaken and washed thrice with HBSS, and electrophoretic mobility shift assay was carried out as described. The upper and lower arrows indicate the induced C/EBPβ band and the unbound probe, respectively. B, BV-2 cells plated at 50–60% confluence in 12-well plates were cotransfected with 0.5 μg of pC/EBPβ-Luc (an C/EBPβ-dependent reporter construct) and 25 ng of pRL-TK. After 24 h of transfection, BV-2 cells were stimulated with different concentrations of female (○), male (●), and castrated male (Δ) MBP-primed T cells. After 1 h of stimulation, T cells were removed followed by the incubation of adherent BV-2 cells in serum-free media for another 5 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were obtained by analyzing total cell extract of BV-2 cells. Data are mean ± S.D. of three different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although the etiology of MS is not completely understood, studies of MS patients suggest that the observed demyelination in the CNS is a result of a T cell-mediated autoimmune response (8). According to one hypothesis, T cells may be activated in spleen and lymph nodes, organs that have been found to contain myelin basic protein (MBP) mRNA and protein in mouse, rat, and human (36). In contrast, according to the other view, T cells may be activated in the CNS periphery by the first encounter with myelin-related autoantigens such as MBP, proteolipid protein, and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (37). However, it is widely believed that after activation these potentially damaging T cells may cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the CNS, where they recognize autoantigens, proliferate, and trigger a broad spectrum inflammatory cascade leading to myelin degradation and clinical symptoms (8, 38, 39). The fact that females are more susceptible to MS than male suggests that neuroantigen-primed T cells cause relatively more CNS damage in females than males. However, despite extensive studies, it is not clearly understood why neuroantigen-primed T cells cause damage specifically in the female CNS.

Several lines of evidence presented in this manuscript clearly support the conclusion that microglial expression of proinflammatory molecules by neuroantigen-primed T cell contact is gender-sensitive. This conclusion is based on the following observations. First, female MBP-primed T cells induced the production of NO and the expression of iNOS in mouse BV-2 microglial cells and primary microglia. This effect was dose-dependent and it peaked at 0.7:1 or 0.5:1 of T cell:microglia. Gene array analyses showed that, apart from the induction of iNOS, female MBP-primed T cells were also capable of inducing the expression of IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6. Second, male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) in BV-2 microglial cells and primary microglia. However, after castration, MBP-primed T cells isolated from castrated male mice induced the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) in microglia suggesting a key role of endogenous male sex hormone in determining this contact activity of neuroantigen-primed T cells. Third, plasma membranes of female and castrated male but not male MBP-primed T cells were also capable of inducing the production of proinflammatory molecules in mouse primary microglia. Fourth, there was no defect in male microglia as MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male mice induced the expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines in male primary microglia. On the other hand, male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce proinflammatory molecules either in female or male microglia. These studies suggest that male are probably protected against MS or EAE due to defective neuroantigen-primed T cells, which are unable to induce the expression of proinflammatory molecules in microglia by cell-cell contact.

Due to gender-related difference in susceptibility to MS, Voshkul and colleagues (32) have correlated the production of NO and the expression of iNOS with EAE onset and severity in female and male SJL/J mice. Similar to the disease susceptibility, iNOS mRNA, enzyme activity, and NO production were higher in female mice with more severe adoptive EAE as compared with male mice with less severe disease. These studies suggested that either gender-related differences in iNOS expression might contribute to gender-related differences in EAE or gender-related differences in EAE might contribute to gender-related differences in iNOS expression. Our results clearly indicate that, in contrast to female neuroantigen-primed T cells, male neuroantigen-primed T cells are not capable of inducing proinflammatory molecules in microglia. Therefore, gender-related difference in iNOS expression in the CNS of SJL/J mice could be due to gender-related differences in microglial activation by neuroantigen-primed T cell contact.

Sedgwick et al. (40) have shown that microglia and T cells do interact in vivo. In the graft-versus-host disease model, activated microglia were found to cluster around T cell infiltrates and to be associated with single or clustered microglia (40). Furthermore, microglia isolated from animals of graft-versus-host disease proliferated and exhibited functions of activated microglia, such as phagocytosis and motility (40). In light of these in vivo observations, and the proximity of activated T cells and microglia in the perivascular space or CNS parenchyma of MS lesions (41), the gender-specific microglial induction of proinflammatory molecules like iNOS, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 by the contact between MBP-primed T cells and microglia described in this manuscript is relevant to the gender bias in MS. The in vitro model of our study shows marked microglial induction of proinflammatory molecules by very few female or castrated male neuroantigen-primed T cells used in the ratio of 0.2:1 of T cells to microglia. At present, it is unclear if this is a relevant ratio. In light of the fact that microglia constitute only 2–5% of total CNS cells in normal brain (42), the present study suggests that infiltration of a very few neuroantigen-primed T cells would be sufficient to activate female but not male CNS microglia for contact-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines. In fact, Cross et al. (43) has shown that the antigen-specific T cells in adoptive transfer model of EAE in female SJL/J mice constitute a minority population (only <2% of the total cell infiltrate into the CNS parenchyma). Although the homing of huge numbers of nonantigen-specific T cells and other blood cells into the CNS after the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier multiplies the inflammatory response and aggravates the disease condition in MS and EAE, the minority population (neuroantigen-primed T cells) is instrumental to initiate the disease process and to induce fresh relapse in MS and EAE (8, 37-39). Therefore, our results delineate a potential mechanism by which a few number of neuroantigen-primed T cells may initiate the inflammatory response in the naïve CNS of female but not male by activating microglia through cell-cell contact.

The signaling events in the induction of proinflammatory molecules are poorly understood. Promoter regions of different proinflammatory molecules (iNOS, IL-1β, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-6) contain consensus sequences for the binding of different transcription factors especially NF-κB and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP)β (34, 35, 44). Inhibition of NF-κB and C/EBPβ by either chemical inhibitors or dominant-negative mutants also leads to the inhibition of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokine expression (24, 34, 35, 45) suggesting an essential role of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in the induction of these proinflammatory molecules. Inhibition of female MBP-primed T cell contact-mediated microglial induction of proinflammatory molecules by Δp65, a dominant-negative mutant of p65, and ΔC/EBPβ, a dominant-negative mutant of C/EBPβ, clearly indicates an important role of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in microglial induction of proinflammatory molecules by T cell contact. Because male MBP-primed T cells were unable to induce the expression of proinflammatory molecules in microglia, to unravel the mystery further, we investigated the activation of NF-κB and C/EBPβ in microglia by MBP-primed T cells isolated from male, female, and castrated male mice. Our results clearly suggest that microglial activation of C/EBPβ but not NF-κB by MBP-primed T cell:microglial contact is a gender-specific event. First, MBP-primed T cells from female and castrated male mice induced microglial activation of both NF-κB and C/EBPβ. Second, MBP-primed T cells from male mice induced the activation of only NF-κB but not C/EBPβ in microglia. Due to the fact that microglial induction of proinflammatory molecules by MBP-primed T cell contact depends on the activation of both NF-κB and C/EBPβ, these results suggest that male MBP-primed T cells are not capable of inducing proinflammatory molecules in microglia due to their inability to induce microglial activation of C/EBPβ.

At present, it is not known which important contact molecule is absent or defective on the surface of male but not female and castrated male MBP-primed T cells. Activated T cells are known to express several integrins on their surface. Recently we have shown that functional blocking antibodies against α4 integrin blocked the ability of female MBP-primed T cells to induce contact-mediated expression of iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines in microglia (22, 23). Interestingly, same functional blocking antibodies suppress the ability of female MBP-primed T cells to induce microglial activation of C/EBPβ but not NF-κB (23). Therefore, the inability of male but not female MBP-primed T cells to induce contact-mediated activation of C/EBPβ in microglia suggests that male but not female MBP-primed T cells probably lack the function of α4-containing heterodimer(s). The α4 integrin is known to function mainly through either α4β1 or α4β7 suggesting that male but not female MBP-primed T cells are probably defective in α4, β1, and/or β7. Further studies are underway in our laboratory to investigate this possibility.

The abbreviations used are

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- iNOS

inducible nitric-oxide synthase

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Multiple Sclerosis Society Grant RG3422A1/1 and National Institutes of Health Grants R01NS39940 and P20RR18759.

References

- 1.Duquette P, Pleines J, Girard M, Charest L, Senecal-Quevillon M, Masse C. Can J Neurol Sci. 1992;19:466–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voskuhl RR, Palaszynski K. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:258–270. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voskuhl RR, Pitchekian-Halabi H, MacKenzie-Graham A, McFarland HF, Raine CS. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:724–733. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roubinian JR, Talal N, Greenspan JS, Goodman JR, Siiteri PK. J Exp Med. 1978;147:1568–1583. doi: 10.1084/jem.147.6.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makino S, Kunimoto K, Muraoka Y, Katagiri K. Jikken Dobutsu. 1981;30:137–140. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.30.2_137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato EH, Ariga H, Sullivan DA. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2537–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin R, McFarland HF, McFarlin DE. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:153–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benveniste EN. J Mol Med. 1997;75:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s001090050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bo L, Dawson TM, Wesselingh S, Mork S, Choi S, Kong PA, Hanley D, Trapp BD. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:778–786. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagsra O, Michaels FH, Zheng YM, Bobroski LE, Spitsin SV, Fu ZF, Tawadros R, Koprowski H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;92:12041–12045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brenner T, Brocke S, Szafer F, Sobel RA, Parkinson JF, Perez DH, Steinman L. J Immunol. 1997;158:2940–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper DC, Bagasra O, Marini JC, Zborek A, Ohnishi ST, Kean R, Champion JM, Sarker AB, Bobroski L, Farber JL, Akaike T, Maeda H, Koprowski H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2528–2533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper DC, Spitsin S, Kean RB, Champion JM, Dickson GM, Chaudhry I, Koprowski H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:675–680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyor WR, Glass JD, Baumrind N, McArthur JC, Griffin JW, Becker PS, Griffin DE. Neurology. 1993;43:1002–1009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.5.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brosnan CF, Raine CS. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharief MK, Hentges R. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:467–472. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maimone D, Gregory S, Arnason BG, Reder AT. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;32:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90073-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruddle NH, Bergman CM, McGrath KM, Lingenheld EG, Grunnet ML, Padula SJ, Clark RB. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1193–1200. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samoilova EB, Horton JL, Hilliard B, Liu TS, Chen Y. J Immunol. 1998;161:6480–6486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esiri MM, Gay D. In: Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical and Pathogenetic Basis. Raine CS, McFarland HF, Tourtellotte WW, editors. Chapman & Hall; London: 1997. pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dasgupta S, Jana M, Liu X, Pahan K. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39327–39333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111841200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasgupta S, Jana M, Liu X, Pahan K. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22424–22431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301789200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jana M, Dasgupta S, Saha RN, Liu X, Pahan K. J Neurochem. 2003;86:519–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giulian D, Baker TJ. J Neurosci. 1986;6:2163–2178. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-08-02163.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jana M, Liu X, Koka S, Ghosh S, Petro TM, Pahan K. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44527–44533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106771200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pahan K, Sheikh FG, Liu X, Hilger S, McKinney M, Petro TM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7899–7905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008262200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jana M, Dasgupta S, Liu X, Pahan K. J Neurochem. 2002;80:197–203. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X, Jana M, Dasgupta S, Koka S, He J, Wood C, Pahan K. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39312–39319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205107200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding M, Wong JL, Rogers NE, Ignarro LJ, Voskuhl RR. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;77:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao J, Mackman N, Edgington TS, Fan ST. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17795–17801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu HM, Tian Q, Baer M, Spooner CJ, Williams SC, Johnson PF, Schwartz RC. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16373–16381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910269199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, MacKenzie-Graham AJ, Palaszynski K, Liva S, Voskuhl RR. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iglesias A, Bauer J, Litzenburger T, Schubart A, Linington C. Glia. 2001;36:220–234. doi: 10.1002/glia.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Utz U, McFarland HF. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:351–358. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chabot S, Yong VW. Neurology. 2000;55:1497–1505. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.10.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sedgwick JD, Ford AL, Foulcher E, Airriess R. J Immunol. 1998;160:5320–5330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traugott U, Reinherz EL, Raine CS. Science. 1983;218:308–310. doi: 10.1126/science.6217550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Baltuch G. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:219–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cross AH, O’Mara T, Raine CS. Neurology. 1993;43:1028–1033. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.5.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Udalova IA, Knight JC, Vidal V, Nedospasov SA, Kwiatkowski D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21178–21186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heiss E, Herhaus C, Klimo K, Bartsch H, Gerhauser C. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32008–32015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]