Abstract

Based on early studies, it was hypothesized that expression of Fas ligand (FasL) by tumor cells enabled them to counterattack the immune system, and that transplant rejection could be prevented by expressing FasL on transplanted organs. More recent studies have indicated that the notion of FasL as a mediator of immune privilege needed to be reconsidered, and taught a valuable lesson about making broad conclusions based on small amounts of data.

The history of science is full of ideas that are at once so elegant and so obvious that they take root in our imaginations, despite relatively weak support by available data. One such idea now in the tumor immunology community is that tumor cells use a molecule called Fas ligand (FasL) to counter-attack the immune system1. Despite substantial evidence to the contrary, this molecule is thought by some to induce the death and elimination of T lymphocytes that enter the tumor bed, thereby granting the tumor immune-privileged status. But this idea is based on inference: all well-controlled experiments in which FasL expression is induced in a tumor or tissue, either through use of transgenic mice or by transfection or transduction of transplanted cells, have shown that the tissue is rapidly rejected, without evidence of immune privilege.

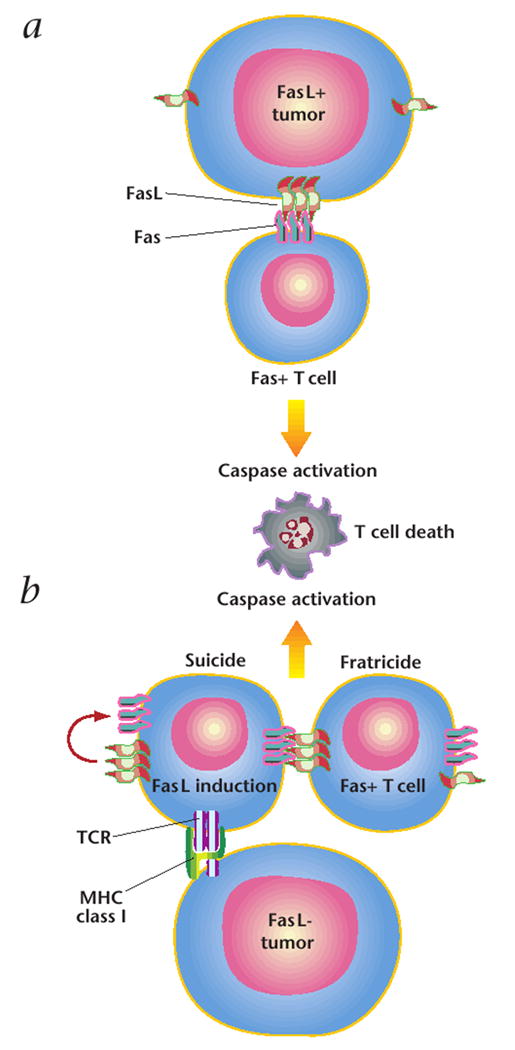

The original idea was logical. FasL expressed on tissues would engage the Fas receptor expressed on the surfaces of immune cells, causing them to undergo programmed cell death (Fig. 1). The idea that FasL (also known as CD95 ligand or APO-1 ligand) could help tumors counter-attack the immune system has its origins in the field of transplantation. However, several early papers containing evidence initially thought to support the hypothesis that FasL could grant immune-privileged status have now been withdrawn or refuted.

Fig. 1. FasL-induced T cell death.

a, Early experiments indicated that FasL, expressed on tumor cells, interacts with its receptor, Fas, which is expressed on invading T cells. This interaction would trigger T-cell death, through caspase activation, and grant the tumor immune privilege. b, Recent studies have shown that FasL is expressed by T lymphocytes after tumor recognition and T cell activation. T cells then kill themselves (‘suicide’) and each other (‘fratricide’) through the same caspase-based mechanism.

The concept was brought to popular attention in a News and Views article published in Nature in October 1995 (ref. 2). The author summarized findings demonstrating that Sertoli cells expressing FasL could be transplanted into allogeneic mice and concluded, based on the data, that the interaction of Fas and its ligand was at the heart of immune privilege3. Another group then reported that transplanted tissue could be protected from rejection if one simply surrounded tissue (in this case the insulin-producing Islet cells of the pancreas) with myoblasts expressing FasL (ref. 4). Fas–FasL interactions were also reported to be fundamental to immune privilege in the eye5. The implications of these findings were great: Graft rejection could be prevented if cells or organs were transfected with FasL before transplantation.

Shortly after these initial publications, two sets of data were published that had a substantial effect on the tumor immunology community, catalyzing a flurry of research activity based on these findings. The first described FasL expression by colon tumor cells, claiming that this induced cell death of Jurkat cells (a human T-cell leukemia line)6. The second described a similar set of results using melanoma7. The latter demonstrated a remarkable consistency of FasL expression in tumor cell samples: All of the 10 melanomas tested expressed FasL. Moreover, it showed that this FasL was functional. The authors also claimed that infiltrating T cells could only be found proximal to FasL-positive lesions of human metastatic melanoma, a finding at odds with many other observations of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Furthermore, the authors reported that the highly virulent mouse melanoma cell line, B16, was FasL-positive. The authors asserted that FasL expression by B16 caused rapid tumor formation.

After those reports, it seemed that the evidence on the function of FasL in transplantation, autoimmunity and tumor escape was clear and compelling. But some other experimental data did not fit the newly established paradigm of FasL as the enforcer of immune privilege. When Allison et al. used transgenic mice expressing FasL on their islet β cells for transplantation, they found that rather than being the solution to the transplantation immunologist’s rejection problem, expression of FasL caused a more rapid rejection of islet cells accompanied by a “granulocytic infiltration” (ref. 8). Kang et al. used an entirely different approach to test the same question, using adenoviruses to confer FasL expression on islet cells. They also found accelerated rejection accompanied by “massive neutrophilic infiltrates” (ref. 9). Similar results were obtained using other cells10,11. Over the two years that followed, Seino et al. would publish many papers testing a possible use for FasL in transplantation, but their data refuted the idea that conferring FasL expression on transplants would be therapeutically useful as originally described6,12-15. Instead, ectopic FasL expression caused rapid rejection and profound inflammation with abscess formation.

In vitro and in vivo experiments with tumor cells also contradicted the original hypothesis that FasL mediated an immune counter-attack. Some investigators claimed that they could not find FasL on the surfaces of melanoma cells16,17, and when they transfected tumor cells with the gene encoding FasL, they did not detect ‘tumor escape’. Instead, there was rapid tumor rejection in many experimental tumor systems (including the B16 melanoma)10,17. As with other FasL-based transplantation experiments, rejected tumors sites were infiltrated with granulocytes that coalesced into abscesses. Soluble FasL can, in part, abrogate the inflammatory effects of membrane-bound FasL (ref. 18).

So why did FasL trigger inflammation? A definitive answer to this question is unknown. However, it is clear that Fas signaling activates a caspase cascade. One consequence of this cascade is the activation of interleukin-1β-converting enzyme (ICE), also known as caspase 1 (ref. 19). As its name indicates, ICE is capable of cleaving interleukin-1β from its inactive form into its active form20. Once activated, interleukin-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine. ICE also cleaves and activates IL-18: the disabling of ICE is a strategy used by poxviruses to evade immune destruction21.

Although some early authors sought to retract their earlier statements, others ‘stuck to their guns’. It was important for transplant immunologists to correct their original mistakes, as transplants engineered to express FasL could prove to be disastrous, leading to rapid rejection and abscess formation rather than increased tissue engraftment. Vaux, who wrote one of the earliest and clearest descriptions of FasL as the ‘enforcer’ of immune privilege, took the unusual step of retracting his News and Views piece after his own lab found inflammation, not immunosuppression2.

The continued proliferation of erroneous ideas about FasL may have been due in part to technical problems hindering early research. A principal problem involved the antibodies used in the early reports. A polyclonal antibody against human FasL (C-20), produced by Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, was not highly specific22, leading to the publication of false-positive results on a least a half-dozen different occasions by the time its cross-reactivity was discovered in 1998, and in several reports by others since then23. Compounding the problem may be the fact that many other polysera were generated in a similar way24, but were not tested in 1998 report22. An underlying and ongoing problem is the use of polysera made by injecting animals with peptides. Although the generation of polyclonal antibodies is straightforward, a complete characterization of antibody specificity is difficult and fraught with pitfalls. Another widely used reagent, a mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 33) from Transduction Laboratories, was also reported to be nonspecific for FasL (ref. 25).

Other possible confounding variables include the use of non-intron-spanning PCR primers without proper controls7,26, contamination of fresh tumor samples with lymphocytes (which can express large amounts of FasL) and problems with functional assays. For example, several studies involved T-cell targets that were themselves capable of expressing FasL, such as Jurkat cells. When target cell death was found and blocked with antibodies against FasL, researchers were not always able to verify that the cell death was induced by FasL expression on tumor cells and not by induced expression of FasL on T cells26. Thus, the devil really was in the details.

One consequence of these misunderstandings, for tumor immunology, was that researchers have been side-tracked in determining the true biological function of Fas and FasL as mediators of cytotoxicity27and as central mediators of activation-induced cell death28. Thus, it is the case that Fas-FasL interactions can cause T cell death and this death is important in the induction of tolerance, immune homeostasis and lymphocyte effector functions. Indeed, it has been confirmed that melanoma-specific T lymphocytes undergo apoptotic death after the major-histocompatibility-complex-restricted recognition of tumor cells, and T-cell death can be blocked by the addition of a specific antibodies against Fas (ref. 29). However, contrary to the prevailing view that tumor cells cause the death of anti-tumor T cells by expressing FasL, it is now apparent that in most cases, FasL is expressed by T lymphocytes upon activation after tumor cell recognition, causing them to kill themselves (‘suicide’) and each other (‘fratricide’) (Fig. 1)16,29,30. When FasL is expressed ectopically with the goal of inducing the death of T lymphocytes, researchers must consider the resultant caspase cascade and the potential for the consequent activation of an innate immune response.

Hindsight is always perfect, and it is now possible to view initial mistakes and contradictory data regarding the function of FasL in a new light. A tantalizing new idea, featured prominently in the literature, can rapidly spread through the scientific community. Once a widely believed hypothesis is re-evaluated, ‘cool’ negative results may not receive the same attention as ‘hot’ positive results. Furthermore, corrections and retractions, as in politics, are often hidden in less-than-obvious places, such as during the question-and-answer periods of lectures, or in abstracts or posters at scientific meetings. It may be true that science is a self-correcting enterprise, and theories come and go, but even in this age of rapid communication, the progress of truth can be glacially slow. Scientific researchers and journal editors must be ever-wary of elegant and intuitively obvious ideas that are only weakly supported by available data.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks D. Chappell, T. Zaks, P. Henkart, S. Rosenberg and M. Lenardo for help with experiments and ideas described above.

References

- 1.O’Connell J, Bennett MW, O’Sullivan GC, Collins JK, Shanahan F. Fas counter-attack—the best form of tumor defense? Nature Med. 1999;5:267–268. doi: 10.1038/6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaux DL. Immunology. Ways around rejection. Nature. 1995;377:576–577. doi: 10.1038/377576a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; retraction. 1998;394:133. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellgrau D, Gold D, Selawry H, Moore J, Franzusoff A, Duke RC. A role for CD95 ligand in preventing graft rejection. Nature. 1995;377:630–632. doi: 10.1038/377630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; erratum. 1998;394:133. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau HT, Yu M, Fontana A, Stoeckert CJJ. Prevention of islet allograft rejection with engineered myoblasts expressing FasL in mice. Science. 1996;273:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffith TS, Brunner T, Fletcher SM, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yagita H, Seino K, Kayagaki N, Okumura K. CD95 ligand in graft rejection. Nature. 1996;379682 doi: 10.1038/379682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahne M, Rimoldi D, Schroter M, et al. Melanoma cell expression of Fas(Apo-1/CD95) ligand: implications for tumor immune escape. Science. 1996;274:1363–1366. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allison J, Georgiou HM, Strasser A, Vaux DL. Transgenic expression of CD95 ligand on islet beta cells induces a granulocytic infiltration but does not confer immune privilege upon islet allografts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3943–3947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang SM, et al. Fas ligand expression in islets of Langerhans does not confer immune privilege and instead targets them for rapid destruction. Nature Med. 1997;3:738–743. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang SM, Lin Z, Ascher NL, Stock PG. Fas ligand expression on islets as well as multiple cell lines results in accelerated neutrophilic rejection. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:538. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang SM, Hoffmann A, Le D, Springer ML, Stock PG, Blau HM. Immune response and myoblasts that express Fas ligand. Science. 1997;278:1322–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seino K, et al. Attempts to reveal the mechanism of CD95-ligand-mediated inflammation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1942–1943. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seino K, et al. Chemotactic activity of soluble Fas ligand against phagocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:4484–4488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seino K, Kayagaki N, Fukao K, Okumura K, Yagita H. Rejection of Fas ligand-expressing grafts. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:1092–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seino K, Kayagaki N, Bashuda H, Okumura K, Yagita H. Contribution of Fas ligand to cardiac allograft rejection. Int Immunol. 1996;8:1347–1354. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.9.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chappell DB, Zaks TZ, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Human melanoma cells do not express Fas (Apo-1/CD95) ligand. Cancer Res. 1999;59:59–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arai H, Gordon D, Nabel EG, Nabel GJ. Gene transfer of Fas ligand induces tumor regression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13862–13867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohlbaum AM, Moe S, Rothstein AM. Opposing Effects of Transmembrane and Soluble Fas Ligand Expression on Inflammation and Tumor Cell Survival. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muzio M, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death—inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, et al. Mice deficient in IL-1β-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1β and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell. 1995;80:401–411. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray CA, et al. Viral inhibition of inflammation: cowpox virus encodes an inhibitor of the interleukin-1β converting enzyme. Cell. 1992;69:597–604. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith D, Sieg S, Kaplan D. Technical note: Aberrant detection of cell surface Fas ligand with anti-peptide antibodies. J Immunol. 1998;160:4159–4160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gastman BR, et al. Fas ligand is expressed on human squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck, and it promotes apoptosis of T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5356–5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Maria R, et al. Functional expression of Fas and Fas ligand on human gut lamina propria T lymphocytes. A potential role for the acidic sphingomyelinase pathway in normal immunoregulation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:316–322. doi: 10.1172/JCI118418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiedler P, Schaetzlein CE, Eibel H. Constitutive expression of FasL in thyrocytes. Science. 1998;279:2015a. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ekmekcioglu S, et al. Differential increase of Fas ligand expression on metastatic and thin or thick primary melanoma cells compared with interleukin-10. Melanoma Res. 1999;9:261–272. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henkart PA, Williams MS, Zacharchuk CM, Sarin A. Do CTL kill target cells by inducing apoptosis? Semin Immunol. 1997;9:135–144. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenardo M, et al. Mature T lymphocyte apoptosis—immune regulation in a dynamic and unpredictable antigenic environment. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:221–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaks TZ, Chappell DB, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Fas-mediated suicide of tumor-reactive T cells following activation by specific tumor: selective rescue by caspase inhibition. J Immunol. 1999;162:3273–3279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chappell DB, Restifo NP. T cell-tumor cell: a fatal interaction? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s002620050505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]