Abstract

Understanding the role of DNA damage checkpoint kinases in the cellular response to genotoxic stress requires the knowledge of their substrates. Here, we report the use of quantitative phosphoproteomics to identify in vivo kinase substrates of the yeast DNA damage checkpoint kinases Mec1, Tel1, and Rad53 (orthologs of human ATR, ATM, and CHK2, respectively). By analyzing 2,689 phosphorylation sites in wild-type and various kinase-null cells, 62 phosphorylation sites from 55 proteins were found to be controlled by the DNA damage checkpoint. Examination of the dependency of each phosphorylation on Mec1 and Tel1 or Rad53, combined with sequence and biochemical analysis, revealed that many of the identified targets are likely direct substrates of these kinases. In addition to several known targets, 50 previously undescribed targets of the DNA damage checkpoint were identified, suggesting that a wide range of cellular processes is likely regulated by Mec1, Tel1, and Rad53.

Keywords: mass spectrometry, Mec1, N-isotag, phosphorylation, Rad53

Most cellular processes are regulated by reversible protein phosphorylation, which is controlled by protein kinases and phosphatases (1). Knowledge of the in vivo substrates of a protein kinase is essential to understanding its biological functions. Extensive studies have revealed that kinase–substrate interaction, their subcellular localization, and substrate specificity of protein kinases are all involved in determining their substrates in cells (2). Not surprisingly, a combination of genetic, biochemical, and cell biological studies is needed to determine the kinase–substrate relationship after a candidate protein has been found via either genetic or biochemical studies. To date, identification of candidate kinase substrates has been difficult, because of the transient nature of kinase–substrate interaction and the limited substrate sequence specificity of protein kinases (3). Further, considering the extensive efforts required for further functional studies, new methodologies that are capable of identifying in vivo kinase substrates with minimal false-positives would clearly be of general interest.

Recently, several high-throughput technologies have been developed to screen for candidate kinase substrates, including protein chip and engineered kinases (4, 5). It is noteworthy that these techniques are based on in vitro kinase specificity. Because the concentration, activity, and localization of protein kinases and their substrates are tightly regulated in cells in response to various stimuli, it would be ideal and likely advantageous if kinase substrates could be identified directly from cells under their physiological conditions. Biological mass spectrometry is a widely used tool for the identification of phosphorylation sites of purified proteins or protein complexes (6, 7). Recently, it has been used to profile thousands of phosphorylation in cells (8–10). The enormous complexity of the phosphoproteome revealed from these studies raised an important question of whether specific substrates of protein kinases in cells could be identified on a proteome-wide scale. Considering that many regulatory phosphorylation events in various signal transduction processes often occur to low-abundance proteins in cells, it was unclear whether a phosphoproteomics approach could be developed to identify specific and biologically relevant kinase substrates.

DNA damage checkpoint kinases are important players in the cellular response to DNA damage or replication stress (11). In budding yeast, the conserved PI3K-like kinases Mec1 and Tel1 are at the top of the DNA damage checkpoint signaling cascade, that includes the downstream serine/threonine kinases Rad53, Chk1, and Dun1 (12–15). These checkpoint kinases control many DNA damage-induced responses in cells, including stabilization of replication forks (16), delay in chromosome segregation (17), transcription of specific genes (18), repair of damaged DNA (19), and cell cycle arrest (20). How these checkpoint kinases regulate such a complex and diverse response is not fully understood. In response to DNA damage, many proteins are known to become phosphorylated by DNA damage checkpoint kinases, including Rad55 (21), Mrc1 (22), Pds1 (15), Xrs2 (23), Rpa1 (24), H2a (19), Sae2 (25), Rtt107 (26), Cdc13 (27), and Sml1 (28). There is, however, a lack of global analysis that could provide a more comprehensive view of the targets of the DNA damage checkpoint. Considering that we still have limited knowledge of the molecular basis of the functions of Mec1, Tel1, Rad53, and Dun1, such a global analysis could be very informative.

In this study, we used a quantitative phosphoproteomics approach to identify novel targets of the DNA damage checkpoint kinases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. By quantitatively comparing the phosphorylation profiles of wild-type (WT) cells and kinase-null mutants, we determined those phosphorylation sites that are specifically altered in various kinase-null mutants. Sequence analysis of the phosphopeptides, in combination with biochemical analysis, of the newly identified targets here showed that direct substrates of Mec1/Tel1 and Rad53 have been identified. Indeed, a number of previously unknown targets, in addition to several known targets, of the DNA damage checkpoint have been found by using this phosphoproteomics approach.

Results

Quantitative Proteomic Approach for Comparative Analysis of Protein Phosphorylation in Cells.

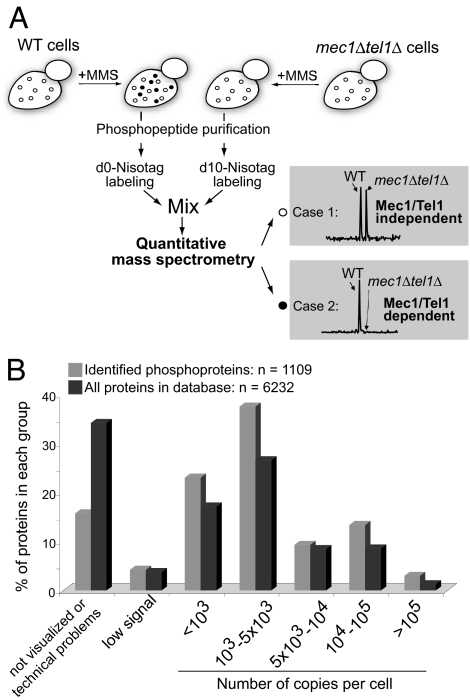

To identify in vivo targets of DNA damage checkpoint kinases, we designed a quantitative phosphoproteomic approach to screen for Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation in cells (see Fig. 1A). Phosphopeptides were purified from WT and mec1Δtel1Δ cells after treatment with the DNA alkylating agent methyl methane sulfonate (MMS), which should lead to specific accumulation of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation in WT cells. After cell lysis, 50 mg of proteins was digested by trypsin and purified by immobilized metal-affinity chromatography. The same amount of phosphopeptides from each sample was then labeled by N-isotag (6), combined, and subjected to 2D liquid chromatography–tandem MS for identification and quantification of their relative abundance. A total of 2,689 nonredundant phosphorylation sites were identified from 1,109 proteins [see supporting information (SI) Table 4]. To assess whether phosphorylation from low-abundant proteins was identified, we retrieved the expression levels of these phosphoproteins according to Ghaemmaghami et al. (29). As shown in Fig. 1B, phosphorylation was detected from proteins of low abundance (<1,000 copies per cell). Comparison of the abundance distribution of the identified phosphoproteins to that of the entire yeast proteome reveals that our list of identified phosphoproteins is not biased toward more abundant proteins. Proteins from different abundance ranges appear to be similarly represented, although phosphopeptides from high-abundance proteins were generally identified more times repeatedly (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Strategy to identify targets of Mec1 and Tel1 in yeast. (A) WT and mec1Δ tel1Δ cells were treated with MMS to induce accumulation of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation (black circles), specifically in WT cells. Phosphopeptides were purified and then labeled by the N-isotag reagent (d0-Leu-NHS for WT and d10-Leu-NHS for mec1Δ tel1Δ cells). Labeled phosphopeptides were then combined and analyzed by 2D liquid chromatography–tandem MS. Based on their relative abundance, phosphopeptides (and the corresponding phosphorylation sites) were then determined to be either independent of (case 1) or dependent on Mec1 and Tel1 (case 2). (B) Comparison of the distribution of proteins in each abundance range for the identified phosphoproteins (gray bars) and the total yeast proteome (black bars). Information on protein abundance was retrieved from Ghaemmaghami et al. (29).

Analysis of Mec1- and Tel1-Dependent Phosphorylation Sites.

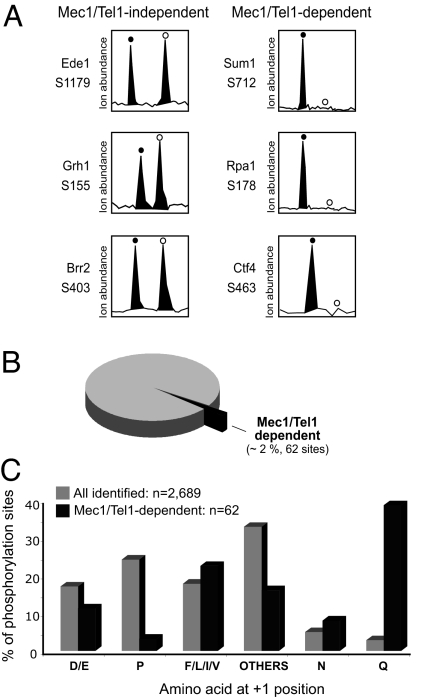

To determine which phosphorylation sites depend on Mec1 and Tel1, we next examined the relative abundance of each phosphopeptide in WT and mec1Δtel1Δ cells. Most of the phosphopeptides were present at similar abundances in WT and mec1Δtel1Δ cells, as revealed by an abundance ratio within 2-fold (exemplified in Fig. 2A Left). To be considered Mec1/Tel1-dependent, a phosphorylation must be identified in a phosphopeptide that was either absent or considerably reduced in abundance (>4-fold) in mec1Δ tel1Δ cells (exemplified in Fig. 2A Right). As shown in Fig. 2B, only 62 phosphopeptides (≈2% of the total identified phosphopeptides) from 55 different proteins were found to be Mec1/Tel1-dependent. We then examined whether direct targets of Mec1 and Tel1 were found. Because Mec1 and Tel1 phosphorylate S/T-Q sites (30), we calculated the frequency of the amino acid residue at the +1 position of all of the phosphorylation sites identified (see Fig. 2C). Interestingly, although phosphorylation of the S/T-Q motif accounts for ≈3% of all phosphorylation sites identified, it represents 39% of the Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. In contrast, proline-directed phosphorylation is very common among all of the identified phosphopeptides, yet only two such phosphorylation sites were found to be Mec1/Tel1-dependent. Therefore, the list of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation is likely enriched for direct targets of Mec1 and Tel1.

Fig. 2.

Identification and analysis of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. (A) Relative ion abundances of selected phosphopeptides (with the indicated phosphorylation site) in WT (filled circles) and mec1Δ tel1Δ (open circles) cells. (Left) Example of phosphopeptides present at similar abundance in both cells, thereby containing a Mec1/Tel1-independent phosphorylation. (Right) Example of phosphopeptides specifically present in wild-type cells, thereby containing a Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. For these Mec1/Tel-dependent phosphorylations, the open circles indicate the expected position of the phosphopeptide ions from mec1Δ tel1Δ cells (labeled with d10-Nisotag). (B) Number and percentage of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation identified relative to the total number of phosphorylation sites identified (2,689 phosphorylation sites and 1,109 proteins; see Methods for detailed description of criteria used). (C) Comparison of the frequency of amino acids at the +1 position of phosphorylated serine or threonine for all identified phosphorylation (gray bars) and Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation (black bars).

Analysis of Rad53-Dependent Phosphorylation Sites.

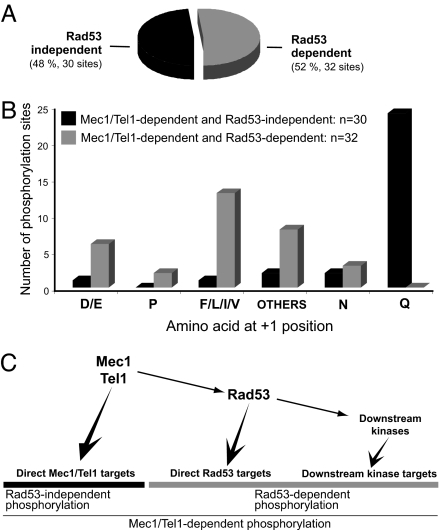

Because Mec1 and Tel1 control the activities of Rad53, Dun1 and possibly other kinases (12, 13, 31, 32), Mec1- and Tel1- dependent phosphorylation should include both direct targets of Mec1 and Tel1 and those of their downstream kinases. Phosphorylation of the S/T-ψ motif (ψ denotes a hydrophobic residue: F, I, L, or V) was also found to be a relatively common Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation, accounting for 23% of these phosphopeptides (see Fig. 2C). We recently showed that Rad53 prefers to phosphorylate Dun1 in its S/T-ψ motif (32). This led us to reason that Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation of the S/T-ψ motif may be directly phosphorylated by Rad53. To test this hypothesis, we performed a similar experiment as shown in Fig. 1A, using rad53Δ cells instead of mec1Δ tel1Δ cells. Of the 2,689 phosphorylation sites consistently found, only 32 were found to be Rad53-dependent and 13 of them are located in a S/T-ψ motif (see Fig. 3 A and B). Importantly, all of them were also identified as Mec1/Tel1-dependent, consistent with Rad53 activity being Mec1/Tel1-dependent.

Fig. 3.

Identification and analysis of Rad53-dependent phosphorylation. (A) Number and percentage (related to total number of Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation identified) of Rad53-dependent phosphorylation identified. All Rad53-dependent phosphorylation was also Mec1/Tel1-dependent (n = 62). (B) Frequency of amino acids at the +1 position of phosphorylated serine or threonine for Rad53-independent and Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation (black bars) and Rad53-dependent phosphorylation (gray bars). (C) Simplified representation of the Mec1, Tel1, and Rad53 kinases and their targets in the DNA damage response.

Because phosphorylation of the majority of the non S/T-Q sites depends on Rad53 (Fig. 3B), Rad53 appears to be the major kinase that functions downstream of Mec1 and Tel1 in yeast samples analyzed 3 h after MMS exposure. Because Rad53 controls the activity of Dun1 and possibly other kinases, it is not surprising that phosphorylation motifs other than S/T-ψ were also found to depend on Rad53 (Table 1). Four phosphorylation sites in a non S/T-ψ motif were detected in Rad53 (S424 and S560) and Dun1 (S10 and S139). These sites were previously found to be autophosphorylation sites through the analysis of purified kinases (6, 32). Their detection here further validated our approach.

Table 1.

Mec1/Tel1-dependent and Rad53-dependent phosphorylation sites identified

| Protein | SGD code | Phosphorylation site | Amino acid at +1* | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dun1 | YDL101C | S10† | G | DNA damage checkpoint |

| S139† | S | |||

| Rad53 | YPL153C | S424† | Y | |

| S560† | N | |||

| Xrs1 | YGL163C | T132 | V | DNA replication and repair |

| Exo1 | YOR033C | S372 | N | |

| Ctf4 | YPR135W | S463 | F | |

| Rnr3 | YIL066C | S806 | P | |

| Tof1 | YNL273W | S626 | E | |

| Shs1 | YDL225W | S221 | F | Cytokinesis |

| Nup1 | YOR098C | S637 | F | Nuclear transport |

| Nup2 | YLR335W | S317 | F | |

| S512 | F | |||

| S523 | F | |||

| Nup60 | YAR002W | S480 | N | |

| Nsp1 | YJL041W | S361 | F | |

| Npl3 | YDR432W | S224 | L | |

| Yrb2 | YIL063C | S14 | E | |

| Mlp1 | YKR095W | S1710 | G | |

| Sec31 | YDL195W | S974 | S | Protein trafficking |

| Uso1 | YDL058W | S1032 | D | |

| Cpr5 | YDR304C | S218 | E | |

| Net1 | YJL076W | S840 | F | Mitosis |

| Cep3 | YMR168C | S575 | L | |

| Pgm2 | YMR105 | S119 | H | Glucose metabolism |

| Rpa14 | YDR156W | S121 | I | Transcription |

| Def1 | YKL054C | S273 | D | |

| Snf2 | YOR290C | S1340 | E | |

| Itc1 | YGL133W | S283 | A | |

| Hpc2 | YBR215W | S(328–330) | S/A | |

| Taf2 | YCR042C | T19 | L | |

| Plm2 | YDR501W | S281 | P | |

Direct Targets of Mec1 and Tel1.

To identify direct Mec1/Tel1 targets, we only considered those Mec1/Tel1-dependent and Rad53-independent phosphorylation sites (see rationale in Fig. 3C). As shown in Table 2, 24 of the 30 phosphorylation sites are located in an S/T-Q motif. This is remarkable because S/T-Q is a relatively rare phosphorylation motif in cells (see Fig. 2C). Clearly, our phosphoproteomic approach has detected the consensus motif preferentially phosphorylated by Mec1 and Tel1. This analysis strongly suggests that most proteins listed in Table 2 are likely direct substrates of Mec1 and/or Tel1. It is interesting to note that most of them are nuclear proteins involved in DNA replication and repair, DNA damage checkpoint, and RNA metabolism and transcription. Among them, Rpa1 and Mec3 were reported to be directly phosphorylated by Mec1 and/or Tel1 (24, 33) and Rad9 was known to undergo a Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation (34, 35). The other targets are previously undescribed findings.

Table 2.

Mec1/Tel1-dependent and Rad53-independent phosphorylation sites identified

| Protein | SGD code | Phosphorylation site | Amino acid at +1* | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rad9 | YDR217C | S989 | S | DNA damage checkpoint |

| Rad17 | YOR368W | S357 | N | |

| Mec1 | YBR136W | S38 | Q | |

| Mec3 | YLR288C | S452 | E | |

| Rpa1 | YAR007C | S178† | Q | DNA replication and repair |

| Abf1 | YKL112W | S193 | I | |

| Cdc2 | YDL102W | S56 | Q | |

| Dpb4 | YDR121W | S183 | Q | |

| Msh6 | YDR097C | S130 | Q | |

| S102 | Q | |||

| Rif1 | YBR275C | S1351 | Q | |

| Mlh1 | YMR167W | S441 | Q | |

| Spt7 | YBR081C | T78 | Q | |

| Cbf1 | YJR060W | S45 | Q | Mitosis |

| S48 | N | |||

| Trm8 | YDL201W | S7 | Q | RNA metabolism |

| Cbf5 | YLR175W | S398/399 | S/Q | |

| Prp19 | YLL036C | S141 | Q | |

| Ysh1 | YLR277C | S517 | Q | |

| Enp1 | YBR247C | S172 | Q | |

| Hsp12 | YFL014W | S21 | Q | Stress response |

| Cyc8 | YBR112C | S780 | Q | Transcription |

| Sok2 | YMR016C | S719 | Q | |

| Hpr1 | YDR138W | S675 | Q | |

| Sum1 | YDR310C | S712 | Q | |

| Asg1 | YIL130W | S166 | Q | |

| Leo1 | YOR123C | S34 | Q | |

| Iws1 | YPR133C | S23 | Q | |

| Nup2 | YLR335W | S399 | Q | Nuclear transport |

| Vma2 | YBR127C | S511 | Q | Vacuole |

*Boldface indicates phosphorylation sites located in the S/T-Q motif.

†Phosphorylation site previously identified (30).

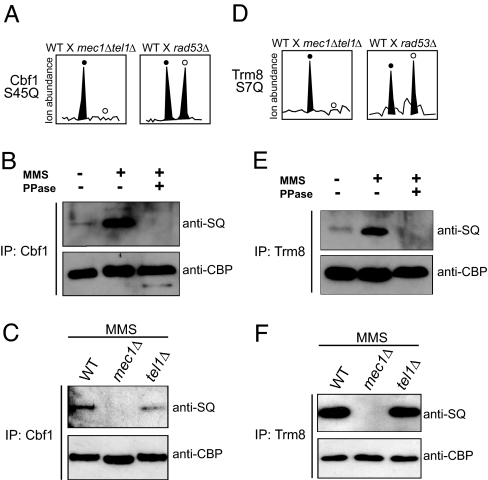

We next addressed whether any new Mec1/Tel1 targets could be validated by other methods and chose to examine Cbf1 and Trm8 further. Both Cbf1 and Trm8 underwent Mec1/Tel1 dependent and Rad53 independent phosphorylation as shown in Fig. 4 A and D. Substrates of Mec1 or Tel1 should be phosphorylated in an MMS-inducible manner. To test whether this is the case for Cbf1 and Trm8, we purified these proteins from untreated and MMS treated cells and detected their phosphorylation using an antibody that specifically recognizes phosphorylated S/T-Q motif. As shown in Fig. 4 B and E, this antibody detected phosphorylation in Cbf1 and Trm8 that is strongly induced by MMS treatment. This signal was abolished by prior phosphatase treatment. Further, the detected phosphorylation of both Cbf1 and Trm8 was found to be mostly dependent on Mec1, less on Tel1 (see Fig. 4 C and F, respectively). These results confirmed that Cbf1 and Trm8 undergo an MMS-induced phosphorylation on an S/T-Q motif.

Fig. 4.

Cbf1 and Trm8 are phosphorylated in an S/T-Q motif, in an MMS-induced manner. (A and D) Relative ion abundance of the Cbf1 and Trm8 phosphopeptides, with phosphorylation at S45 and S7, respectively, in WT (filled circles) and the indicated kinase-null (open circles) cells. (B and E) Western blot analysis of Cbf1 and Trm8 immunoprecipitated (IP) from control or MMS-treated cells and eluted by using TEV protease. Phosphorylated S/T-Q motifs were detected with an antiphospho-S/T-Q antibody. For loading control, the blot was later detected with an anti-CBP antibody. (C and F) Western blot was performed as described in B and E, and proteins were purified from MMS-treated cells lacking the indicated kinases.

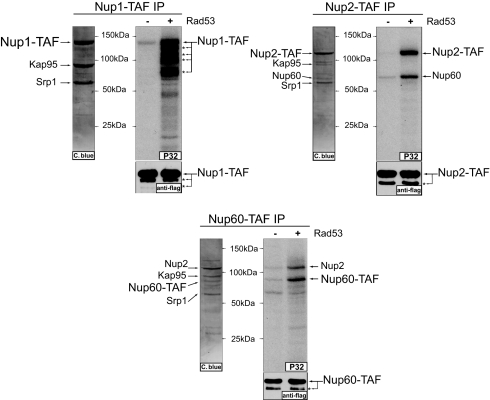

Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC) Components Are Directly Phosphorylated by Rad53.

Next, we asked whether direct targets of Rad53 were found. From the list of targets with a Rad53-dependent phosphorylation in an S/T-ψ motif (see Table 1), we focused on the nucleoplasmic components of the NPC, i.e., Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60. These proteins showed no detectable mobility shift when purified from MMS-treated cells (unpublished observation). We thus used the N-isotag method to analyze the phosphorylation of these proteins after they were purified from untreated and MMS-treated cells. A number of MMS-induced phosphorylation sites of Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 were identified (see Table 3 and SI Tables 5–7). Interestingly, phosphorylation of the S-F motif was most commonly detected, and they were strongly induced by MMS treatment. Further, Rad53 was found to efficiently phosphorylate Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 in vitro (Fig. 5). Importantly, recombinant Rad53 phosphorylated essentially the same MMS-induced sites located in the S-F motifs (see Table 3). These results indicated that Nup1, Nup2 and Nup60 are likely direct substrates of Rad53 and further strengthened the notion that Rad53 prefers to phosphorylate S/T-ψ motif, especially with a phenylalanine at the +1 position.

Table 3.

Quantification of phosphorylation sites detected from purified endogenous proteins

| Protein | Phosphorylation site | Amino acid at +1 | MMS/control ratio | +/- Rad53ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nup1 |

592 | F | >10 | >10 |

| 656 | F | >10 | 8.0 | |

| 615 | F | 7.6 | >10 | |

| 672 | F | 7.6 | >10 | |

| 637 | F | 5.0 | 10.0 | |

| 383 | F | 4.8 | >10 | |

| 449 | F | 3.9 | 4.5 | |

| 754 |

F |

3.3 |

>10 |

|

| Nup2 |

317 | F | >10 | 9.1 |

| 248 | F | >10 | — | |

| 399 | Q | >10 | 1.2 | |

| 368 | F | 9.4 | 8.2 | |

| 68 | F | 9.1 | >10 | |

| 512 | F | 8.4 | 4.3 | |

| 203 | D | 8.0 | 1.0 | |

| 351 | F | 7.0 | 8.0 | |

| 561 | Q | 6.6 | — | |

| 284 | F | 5.6 | 7.4 | |

| 523 |

F |

4.1 |

3.9 |

|

| Nup60 | 360 | F | >10 | >10 |

| 480 | N | >10 | 1.0 | |

| 483 | Q | 4.9 | 1.3 | |

| 382 | P | 3.6 | 1.0 |

Comparison between untreated and MMS-treated cells (second to last column) and with or without in vitro Rad53 phosphorylation (last column). Only MMS-induced phosphorylation sites of Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 are shown (for complete list of phosphorylation sites indentified, see SI Tables 7–9). Boldface indicates the sites phosphorylated by Rad53 in vitro.

Fig. 5.

The nuclear pore proteins Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 are directly phosphorylated by Rad53. Shown are in vitro kinase reactions using recombinant Rad53 and either Nup1, Nup2, or Nup60 complexes purified from untreated cells. Purified comoplexes were stained by Coomassie blue, and indicated bands were indentified by MS. Anti-FLAG Western blot is shown as loading control. Asterisks indicate partially proteolyzed fragments of indicated proteins.

Discussion

Here, we showed the use of quantitative phosphoproteomics to identify in vivo substrates of DNA damage checkpoint kinases. By comparing phosphorylation of WT vs. kinase-null cells in response to DNA damage, specific targets of DNA damage checkpoint kinases were identified. In total, 55 proteins were found to have a phosphorylation controlled by Mec1/Tel1 (see Tables 1 and 2). Because Mec1 and Tel1 regulate the activity of other kinases, including Rad53 and others, further analysis was performed to establish the direct targets of Mec1/Tel1. Interestingly, most of the Mec1/Tel1-dependent and Rad53-independent targets were found to have phosphorylation in the S/T-Q motif, a known consensus of Mec1 and Tel1. Among them, known substrates of Mec1 and Tel1, such as Rpa1 (24, 36), and components of the DNA damage checkpoint, including Rad9, Rad17, Mec3, and Mec1 itself, were found. The other direct Mec1/Tel1 targets identified here are previously undescribed findings, and most of them have roles in transcriptional regulation, RNA metabolism, and DNA replication and repair. These results showed that Mec1 and Tel1 appear to phosphorylate a very diverse network of nuclear proteins directly.

Our results further support the well established role of Rad53 as a downstream effector of Mec1 and Tel1 (37, 38). We note here that some of the Rad53-dependent phosphorylation sites may be due to indirect effects. For example, a proline-directed phosphorylation was detected for Rnr3 (see Table 1). Transcription of Rnr3 was known to be up-regulated after MMS treatment in a Rad53- and Dun1-dependent manner (18). Thus, this phosphorylation of Rnr3 may be related to a change in protein abundance, rather than a DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Rnr3.

Potential direct targets of Rad53 could be inferred based on the knowledge of its preferred consensus phosphorylation motif, S/T-ψ. This was shown for Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60. We found that Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 undergo MMS-induced phosphorylation in vivo, and these same phosphorylation sites are phosphorylated by Rad53 in vitro. Interestingly, Rad53 was known to interact with the karyopherins Kap95 and Srp1 (6), which are also known to bind to Nup1, Nup2 and Nup60 (39) (see Fig. 5). It is possible that Kap95 and Srp1 may function as adaptors to mediate Rad53 phosphorylation of these NPC components in cells. Considering the rather limited substrate sequence specificity of Rad53, it appears that its interaction with potential substrates in cells is important for substrate recognition, analogous to the situation of Dun1 being a substrate of Rad53 (31, 32). The DNA damage checkpoint kinases were known to regulate nuclear export of Rnr2 and Rnr4 (40, 41) and have genetic interactions with NPC components (42, 43). Phosphorylation of the NPC by DNA damage checkpoint kinases could play a role in the DNA damage response.

It is important to point out that not all Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation sites were found in these phosphoproteomic experiments. For example, more phosphorylation sites of Rad53, Dun1, and Rad9 were found when purified proteins were analyzed (6, 32). Also, several known phosphorylation targets in the DNA damage response were not found, including Rad55 (21), Mrc1 (22), Pds1 (15), Xrs2 (23), and others. Other known targets were identified but did not completely fulfill our criteria to be considered, including phosphopeptides of Rtt107 and Cdc13 with a Mec1/Tel1-dependent phosphorylation in an S-Q motif (S255 in Rtt107 and S306 in Cdc13). In the case of H2a, a phosphopeptide with a phosphorylation at S129 (S-Q motif) was identified as Mec1/Tel1-dependent in samples before strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography. Unpublished observation indicated this peptide does not bind to the SCX column. We thus expect that additional targets will be identified with further improvements to this technology and the use of faster and more sensitive mass spectrometers.

It is clear from our analysis that the DNA damage checkpoint kinases directly phosphorylate many proteins with diverse nuclear functions, revealing many processes that may be regulated in response to DNA damage. Our study here represented an initial step toward defining what these targets are, with likely many more to be discovered. Functional analysis of the identified targets is needed for a better understanding of how DNA damage checkpoint kinases coordinate a global DNA damage response. Finally, we suggest this phoshoproteomic approach should be generally applicable to identify in vivo targets of kinases and to characterize phosphorylation-mediated signaling pathways in cells.

Methods

Yeast Methods.

Standard yeast genetic technique and cell growth conditions were used. WT and rad53Δ cells used for the large-scale phosphorylation analysis were derived from the haploid MBS62 (MATα, ura3–52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3–10, ade2Δ1, ade8, and sml1::TRP1). Because SML1 deletion is necessary to suppress the lethality of MEC1 or RAD53 deletion, WT cells referred to here also have SML1 deletion. TAP-tagged Cbf1 and Trm8 were obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). Chromosomal TAF-tagged Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 were generated in RDKY2669 (MATα, ura3–52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3–10, ade2Δ1, and ade8) using homologous recombination technique and the TAF-containing plasmid described elsewhere (32).

Cell Growth and Protein Extraction.

Two liters of yeast cells (WT or kinase-null) were grown in YPD medium to an OD600 of 0.5 and cells were treated with 0.05% MMS for 3 h. Cells were broken in an ice-cooled bead beater with 40 ml of lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 0.2 mM benzamidine, 1 μM leupeptin, and 1.5 μM pepstatin. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min. For each experiment, ≈50 mg of proteins were then denatured by boiling in the presence of 2% SDS and 10 mM DTT for 5 min. Proteins were alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide, precipitated with 3 volumes of cold ethanol:acetone (1:1, vol/vol) and then resuspended with buffer containing 2 M urea and 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0. One milligram of trypsin (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ) was added for overnight digestion, and then the tryptic peptides were desalted by using a 2-g C18 column (Waters, Milford, MA).

Phosphopeptide Purification.

N-isotag labeling and SCX fractionation. Phosphopeptides were purified by using immobilized metal affinity column, as described (6). Eluted phosphopeptides were labeled with either d0-N-isotag (WT cells) or d10-N-isotag (kinase-null cells), as described (44). The labeled phosphopeptides from WT cells were then combined with the labeled phosphopeptides from either mec1Δ tel1Δ or rad53Δ cells and then fractionated using a 2 × 50 mm PolySulfoethyl-based Strong Cation Exchange column (Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ), as described (6).

Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis.

Ten SCX fractions were collected and analyzed by a Thermo Finnigan (Waltham, MA) LTQ quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer. For data analysis, COMET was used for peptide identification (45), and XPRESS and INTERACT softwares were used for quantitation as described (6, 44). The complete yeast database was used to analyze MS/MS spectra with no restriction on the enzyme used. Variable modifications of 80 Da (phosphorylation) on serine and threonine residues and 10 Da (light and heavy N-isotag mass difference) on lysine residues and N terminus were included in the database search. A static modification of 113 Da was included on lysine and N termini of all peptides. Because of oxidation of methionine and tryptophan residues during N-isotag labeling, a static modification of 16 Da was added to these resides. Each large-scale phosphoproteomic experiment (WT vs. mec1Δ tel1Δ cells and WT vs. rad53Δ cells) was repeated five times.

To generate a list of the identified phosphopeptides (SI Table 4), we considered only the top-matched and doubly tryptic phosphopeptides that were identified at least once in each of the experiments (WT vs. mec1Δ tel1Δ cells and WT vs. rad53Δ cells). Using these criteria, we obtained a nonredundant list of 2,457 phosphopeptides, containing 2,689 phosphorylation sites (see SI Table 4). This list of phosphopeptides was then subjected to further more stringent analysis, as described below.

Identification of Mec1/Tel1- or Rad53-Dependent Phosphorylation Sites.

To identify Mec1/Tel1- or Rad53-dependent phosphorylation, we searched for phosphopeptides that fitted three additional criteria (see SI Tables 5 and 6 for detailed information of each peptide): (i) abundance is reduced at least 4-fold in the kinase-null cells, compared with WT cells; (ii) signal-to-noise ratio of the identified parent ion is at least 5-to-1; (iii) the phosphopeptide was identified more times as labeled with d0-N-isotag (WT) than with d10-N-isotag (kinase-null mutant). MS/MS spectra of all of the phosphopeptides that fitted the above three criteria were further manually inspected to confirm the identification of the phosphopeptide and the assignment of the phosphorylation sites.

Western Blot Analysis of Cbf1 and Trm8 Phosphorylation.

One hundred milliliters of Cbf1-TAP and Trm8-TAP cells was grown in YPD medium to an OD600 of 0.5, and cells were either treated with 0.05% MMS for 3 h or mock-treated for 2 h. Cells were then harvested and broken as described above but using 1 ml of lysis buffer instead. The protein extracts were incubated with 20 μl of IgG resin overnight. The IgG resins were then washed extensively by TBS-T and subjected to TEV cleavage (1 unit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to elute proteins. Part of the elution derived from MMS-treated cells was further treated by CIP (5 units, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 1 h. For Western blot analysis, proteins were detected by using antiphospho-S/T-Q antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA) or anti-CBP antibody (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA).

Purification of Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 and in Vitro Kinase Reaction Using Rad53.

Two liters of Nup1-TAF, Nup2-TAF, and Nup60-TAF cells was grown to a density of 1, harvested, and broken as described above. The protein extracts were incubated with 100 μl of IgG resin overnight. The IgG resins were then washed extensively by TBS-T and subjected to TEV cleavage (10 units, Invitrogen) to elute Nup1, Nup2, or Nup60 proteins. Ten percent of the eluted proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining. For in vitro kinase reaction, 12.5 ng of recombinant Rad53 was used to phosphorylate the TEV-eluted Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 for 1 h at 30°C. The amount of Nup1, Nup2, and Nup60 used for each kinase reaction is the same as those shown in the Coomassie-stained gels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Raymond Deshaies and Dr. Richard Kolodner for critical reading and suggestions on this work. This work was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and National Human Genome Research Institute (Grant K22 HG002604, to H.Z.).

Abbreviations

- MMS

methyl methane sulfonate

- SCX

strong cation exchange

- NPC

nuclear pore complex.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701622104/DC1.

References

- 1.Hunter T. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawson T, Scott JD. Science. 1997;278:2075–2080. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning BD, Cantley LC. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:PE49. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.162.pe49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubersax JA, Woodbury EL, Quang PN, Paraz M, Blethrow JD, Shah K, Shokat KM, Morgan DO. Nature. 2003;425:859–864. doi: 10.1038/nature02062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ptacek J, Devgan G, Michaud G, Zhu H, Zhu X, Fasolo J, Guo H, Jona G, Breitkreutz A, Sopko R, et al. Nature. 2005;438:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nature04187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smolka MB, Albuquerque CP, Chen SH, Schmidt KH, Wei XX, Kolodner RD, Zhou H. Mol Cell Proteom. 2005;4:1358–1369. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500115-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shou W, Verma R, Annan RS, Huddleston MJ, Chen SL, Carr SA, Deshaies RJ. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:279–296. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villen J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ficarro SB, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Burke DJ, Ross MM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, White FM. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyberg KA, Michelson RJ, Putnam CW, Weinert TA. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:617–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060402.113540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez Y, Desany BA, Jones WJ, Liu Q, Wang B, Elledge SJ. Science. 1996;271:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun Z, Fay DS, Marini F, Foiani M, Stern DF. Genes Dev. 1996;10:395–406. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Z, Elledge SJ. Cell. 1993;75:1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90321-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, Elledge SJ. Science. 1999;286:1166–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan V, Nirantar S, Crasta K, Cheng AY, Surana U. Mol Cell. 2004;16:687–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Genes Dev. 1990;4:740–751. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downs JA, Lowndes NF, Jackson SP. Nature. 2000;408:1001–1004. doi: 10.1038/35050000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paulovich AG, Hartwell LH. Cell. 1995;82:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bashkirov VI, King JS, Bashkirova EV, Schmuckli-Maurer J, Heyer WD. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4393–4404. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4393-4404.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborn AJ, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1755–1767. doi: 10.1101/gad.1098303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Amours D, Jackson SP. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2238–2249. doi: 10.1101/gad.208701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brush GS, Morrow DM, Hieter P, Kelly TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15075–15080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cartagena-Lirola H, Guerini I, Viscardi V, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1549–1559. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.14.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouse J. EMBO J. 2004;23:1188–1197. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng SF, Lin JJ, Teng SC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6327–6336. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao X, Rothstein R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3746–3751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062502299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim ST, Lim DS, Canman CE, Kastan MB. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37538–37543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bashkirov VI, Bashkirova EV, Haghnazari E, Heyer WD. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1441–1452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1441-1452.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen S, Smolka MB, Zhou H. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:986–995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609322200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majka J, Niedziela-Majka A, Burgers PM. Mol Cell. 2006;24:891–901. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emili A. Mol Cell. 1998;2:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vialard JE, Gilbert CS, Green CM, Lowndes NF. EMBO J. 1998;17:5679–5688. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim HS, Brill SJ. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:1321–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longhese MP, Foiani M, Muzi-Falconi M, Lucchini G, Plevani P. EMBO J. 1998;17:5525–5528. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowndes NF, Murguia JR. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen NP, Huang L, Burlingame A, Rexach M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29268–29274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102629200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YD, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 2006;20:334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1380506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao R, Zhang Z, An X, Bucci B, Perlstein DL, Stubbe J, Huang M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6628–6633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131932100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan X, Ye P, Yuan DS, Wang X, Bader JS, Boeke JD. Cell. 2006;124:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loeillet S, Palancade B, Cartron M, Thierry A, Richard GF, Dujon B, Doye V, Nicolas A. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smolka MB, Chen S, Maddox PS, Enserink JM, Albuquerque CP, Wei XX, Desai A, Kolodner RD, Zhou H. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:743–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller A, Eng J, Zhang N, Aebersold R. Mol Syst Biol. 2005;1:2005.0017. doi: 10.1038/msb4100024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.