Abstract

The streptogramin combination therapy of quinupristin–dalfopristin (Synercid) is used to treat infections caused by bacterial pathogens, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. However, the effectiveness of this therapy is being compromised because of an increased incidence of streptogramin resistance. One of the clinically observed mechanisms of resistance is enzymatic inactivation of the type B streptogramins, such as quinupristin, by a streptogramin B lyase, i.e., virginiamycin B lyase (Vgb). The enzyme catalyzes the linearization of the cyclic antibiotic via a cleavage that requires a divalent metal ion. Here, we present crystal structures of Vgb from S. aureus in its apoenzyme form and in complex with quinupristin and Mg2+ at 1.65- and 2.8-Å resolution, respectively. The fold of the enzyme is that of a seven-bladed β-propeller, although the sequence reveals no similarity to other known members of this structural family. Quinupristin binds to a large depression on the surface of the enzyme, where it predominantly forms van der Waals interactions. Validated by site-directed mutagenesis studies, a reaction mechanism is proposed in which the initial abstraction of a proton is facilitated by a Mg2+-linked conjugated system. Analysis of the Vgb–quinupristin structure and comparison with the complex between quinupristin and its natural target, the 50S ribosomal subunit, reveals features that can be exploited for developing streptogramins that are impervious to Vgb-mediated resistance.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, enzyme mechanism, crystal structure

The streptogramin antibiotic formulation Synercid received accelerated approval from the Food and Drug Administration in 1999 for the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive bacterial pathogens that are resistant to frontline antibiotics, including vancomycin (1). Synercid is a combination of two semisynthetic chemically unrelated derivatives of the streptogramin class of antibiotics: a type A streptogramin (dalfopristin) and a type B streptogramin (quinupristin). Streptogramins are natural products produced by a number of bacteria including Streptomyces pristinaespiralis (pristinamycin) and Streptomyces virginiae (virginiamycin) (2). These drugs block protein translation by binding to the P-site of the ribosome (type A streptogramin) and by occluding the entrance to the peptide exit tunnel (type B streptogramin). Binding of the type A streptogramin results in a conformational change in the ribosome that facilitates binding of the type B streptogramin (3–5). It is this inhibitor-induced conformational change that forms the molecular basis of the synergistic antimicrobial activity that is the hallmark of this class of antibiotics.

Although Synercid was initially marketed specifically for the treatment of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, shortly after its approval by the Food and Drug Administration the antibiotic formulation faced its own challenges (6, 7). Resistance to Synercid can occur through a number of routes, including drug efflux and methylation of the ribosome (8). However, only two clinically relevant mechanisms of antibiotic inactivation have thus far been identified. Type A streptogramins are modified by a cadre of Vat enzymes that catalyze acetylation of the antibiotic (9, 10), and type B streptogramins are inactivated by a ring-opening lyase called virginiamycin B lyase (Vgb) (11).

Vgb was first described in a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus in 1977 (12). It has since been identified on a number of resistance plasmids in various Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. Originally, Vgb was thought to be a hydrolase that was predicted to linearize type B streptogramins through cleavage of the thermodynamically vulnerable ester linkage between the carboxyl of the invariant phenylglycine group and the secondary alcohol of the threonyl moiety. Careful analysis of the reaction and reaction products however demonstrated that Vgb is a C O lyase that linearizes the antibiotic at the ester linkage, generating a free phenylglycine carboxylate and converting the threonyl moiety into 2-amino-butenoic acid. This process remarkably does not involve water but requires a divalent metal ion such as Mg2+ (11).

O lyase that linearizes the antibiotic at the ester linkage, generating a free phenylglycine carboxylate and converting the threonyl moiety into 2-amino-butenoic acid. This process remarkably does not involve water but requires a divalent metal ion such as Mg2+ (11).

Orthologues of Vgb are found embedded in a number of bacterial genomes [supporting information (SI) Fig. 4], and purification of representatives from the soil bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor and Bordetella pertussis, which causes whooping cough, revealed that they also efficiently inactivate type B streptogramins with kcat/Km within 2- to 10-fold of the S. aureus enzyme (11). The presence of these genes in bacterial genomes is unexpected and potentially problematic for the continued use of these antibiotics. In an effort to understand the molecular details of this mechanism, provide a basis for future effort to inhibit the enzyme, or design streptogramins that are not susceptible to its action, we have determined the crystal structure of Vgb in its apoenzyme state and in complex with quinupristin and Mg2+. Furthermore, supported by complementary site-directed mutagenesis studies, we propose a novel catalytic mechanism for metal-assisted cleavage of a C O bond.

O bond.

Results

Structure of Vgb Apoenzyme.

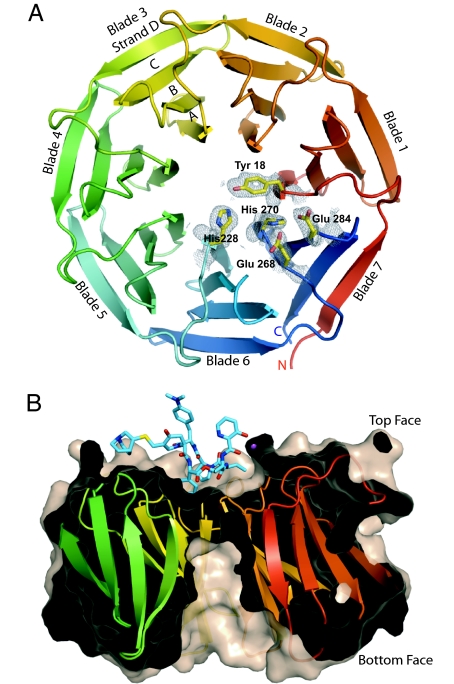

The structure of Vgb from S. aureus in the apoenzyme state was determined in two different crystal forms: to a resolution of 1.65 and 1.9 Å, using a combination of multiwavelength anomalous dispersion and molecular replacement methods (Fig. 1). The Vgb fold consists of seven nearly identical, highly twisted, four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets, arranged in a circular array. The resulting structure is that of a very regular seven-bladed β-propeller fold (e.g., refs. 13 and 14). The overall shape of the enzyme is akin to a doughnut with a diameter of 45 Å and a height of 30 Å, in which the hole is closed off by a ring of aromatic residues (Tyr-18, Tyr-102, Phe-145, and His-228), resulting in a depression of 15 Å wide and 8 Å deep on one side of the protein and a deep tunnel of ≈8 Å wide and 20 Å deep on the opposite face (Fig. 1B). Henceforth we will refer to the side with the depression as the top face. Altogether, five crystallographically independent copies of the apoenzyme state were determined. Pairwise comparison between the five copies returns rmsd values of 0.4–0.7 Å (for all main-chain atoms), and no indication that certain blades are more mobile. On the other hand, four regions reveal variable positions in the models: the N terminus (residues 1–7), two loops (residues 11–15 and 264–268), and the C terminus (residues 292–299).

Fig. 1.

Structure of Vgb from S. aureus. (A) Ribbon diagram of Vgb viewed down the central axis. Five active-site residues are also shown together with their corresponding 2 Fo − Fc density map contoured at 1σ, as observed in the 1.65-Å structure. (B) View rotated 90° about the horizontal axis. The structure is sliced through the center to highlight the depression and the tunnel located on the top and bottom face of Vgb, respectively. Also shown is quinupristin, which binds in the depression.

The symmetric nature of the fold is mirrored in the primary structure of Vgb, which has a 42-residue-long consensus sequence that repeats seven times. This intramolecular consensus sequence has a strictly conserved Trp followed by a semiconserved Phe located on strand B of the four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet near the bottom face and an strictly conserved Ile located on strand C. Intriguingly, this consensus sequence bares no resemblance to repeating motifs observed in other proteins that have a β-propeller architecture, such as the WD40 and Kelch repeats (13, 14). For example, the Trp of the WD40 repeat is located on strand C, where in Vgb a Thr is predominantly positioned (SI Fig. 5). Therefore, Vgb represents an additional member of this diverse structural family.

Structure of Vgb in Complex with Quinupristin and Mg2+.

All attempts to obtain crystals of wild-type Vgb in complex with quinupristin (or analogs thereof), in the absence or presence of Mg2+ failed and only resulted in apoenzyme crystals in the P212121 space group. Site-directed mutagenesis studies targeting histidine residues that are conserved among Vgb orthologues identified two mutations that rendered the enzyme inactive, H228A and H270A (Table 1). Furthermore, upon analysis of crystal contacts present in the apoenzyme crystal form, it was realized that residues 51–56 [PLPTPD] of a neighboring molecule persistently formed packing interactions in close proximity to His-228 and His-270, presumably obstructing the quinupristin-binding pocket (SI Fig. 6). Therefore, we pursued cocrystallizations with the H270A variant where residues 51–56, which are located in the loop connecting the first and second blade, on the top face of the enzyme, were additionally replaced by the sequence of the corresponding loop between blades three and four, residues 135–140 [ELPNKG]. Kinetic analysis indicated that the loop replacement by itself did not adversely affect the activity of Vgb (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of Vgb and mutants

| Enzyme | Km, μM | kcat, s−1 | kcat/Km, M−1·s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 14 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 | 7.8 × 105 |

| Loop change | 16 ± 3 | 11 ± 1 | 7.0 × 105 |

| Y18F | 60 ± 9 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 1.3 × 103 |

| H228A | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| E268Q | 21 ± 4 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 1.4 × 104 |

| H270A | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| E284Q | 20 ± 6 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 5.7 × 103 |

n.a., not available.

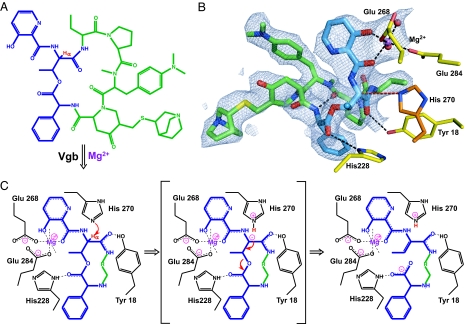

The crystal structure of the Vgb catalytically inactive H270A-loop variant in complex with quinupristin and Mg2+ was determined by molecular replacement at 2.8-Å resolution. There are two Vgb molecules per asymmetric unit, providing two crystallographically independent views of the substrate-bound complex. The fold of the enzyme is essentially identical to that seen in the apoenzyme state (rmsd ≈0.7 Å for all main-chain atoms), indicating that the mutations have no impact on the overall structure. In the crystal structure the quinupristin molecule is located on the top face of the enzyme in close proximity to the mutated H270A where it completely fills the depression (Figs. 1B and 2 A and B). The antibiotic makes specific hydrogen-bond interactions with the side chains of residues Tyr-18 and His-228, which are conserved among Vgb orthologues, and also with the guanidinium group of Arg-226. Additionally there are numerous van der Waals interactions, which are likely responsible for most of the affinity between Vgb and quinupristin. Associated with quinupristin is a Mg2+ ion that interacts via the two oxygen atoms of the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety. The remaining interactions to the Mg2+ ion are provided by two solvent molecules, and the conserved residues Glu-268 and Glu-284, which are stabilized by Trp-243 and His-33, respectively. In comparison to the apoenzyme state the side chains of Gln-160 and Tyr-142 move out of the way to allow for binding of the substrate, whereas Arg-226, Trp-243, Glu-268, and Glu-284 adopt conformations that enable favorable interactions.

Fig. 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for Vgb lyase activity. (A) Chemical structure of quinupristin. The 3-hydroxypicolinic acid, threonyl, and phenylglycyl moieties are colored blue, and the threonyl α-proton is shown in red. (B) Active site of Vgb. Quinupristin is shown using the same color scheme as in A, Mg2+ is shown in purple, active-site residues are displayed in yellow, with the modeled catalytic base His-270 displayed in dark orange, and water molecules are shown as red spheres. Also displayed is the 2Fo − Fc density map contoured at 1σ for quinupristin and Mg2+. (C) Schematic drawing of the proposed reaction mechanism. Note that only a part of quinupristin is shown, the remainder is represented by R.

During crystallization trials, it was noted that crystals of Vgb grown in the presence of quinupristin were of poorer quality than with Synercid, which contains both quinupristin and the structurally unrelated dalfopristin. The crystal structure of the substrate-bound complex reveals a dalfopristin molecule wedged between two Vgb molecules, aiding in crystal packing (SI Fig. 7). Because dalfopristin interacts with residues that are not conserved among Vgb orthologues, there is most likely no biological relevance to this observation. This idea is supported by kinetic studies that show that dalfopristin has no effect on Vgb lyase activity (data not shown).

Mutational Analysis of Vgb.

To probe the molecular mechanism for the lyase reaction catalyzed by Vgb, three additional mutants of residues conserved among Vgb orthologues and that interact with either quinupristin or the associated Mg2+ ion in the substrate-bound structure, were examined: Y18F, E268Q, and E284Q (Table 1). Consistent with the observed interaction between Tyr-18 and quinupristin, the Y18F mutant has a 4-fold reduced affinity for the substrate. Additionally, all three mutants display compromised catalytic efficiency as indicated by significant (10- to 100-fold) reductions in kcat/Km values. These observations suggest that all five residues are involved in catalysis, with critical roles for His-228 and His-270 and ancillary roles for Tyr-18, Glu-268, and Glu-284.

Discussion

Catalytic Mechanism for Vgb.

Crystal structures for the apoenzyme and substrate-bound complex, in combination with mutagenesis studies reported here, are consistent with the mechanism for the linearization of type B streptogramins catalyzed by Vgb shown in Fig. 2C. The substrate-bound complex structure reveals a network of catalytically important interactions between the enzyme, Mg2+, and quinupristin, involving the conserved residues (Tyr-18, His-228, Glu-268, and Glu-284). Mg2+ is coordinated to the oxygen atoms of the conjugated 3-hydroxypicolinic acid group that flanks the Cα atom of the quinupristin-threonyl moiety. Because of the electron-withdrawing properties of Mg2+ the threonyl α-proton is affected, resulting in a decrease of its pKa value. The lowering of the pKa for the α-proton is exacerbated by Tyr-18, which forms a hydrogen bond with a carbonyl group also immediately adjacent to the Cα atom. This hydrogen bond stabilizes the charged resonance structure of the peptide bond, thereby further weakening the Cα–H bond. Modeling of His-270 into the substrate-bound complex of the variant Vgb based on the apoenzyme structures reveals that the Nε2 is within 4 Å of the quinupristin–threonyl Cα atom, with the correct geometry to function as a catalytic base. Hence, the predicted first step in the reaction mechanism for Vgb is deprotonation of quinupristin–threonyl Cα by His-270, facilitated by Mg2+ and Tyr-18. The resultant negative charge on the Cα atom does not delocalize over an expanded conjugated system, presumably because the π-orbitals for the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety and the peptide bond are not oriented parallel to each other. Instead, in the second step of the reaction, a rearrangement of the electrons takes place, which results in double-bond formation between the Cα and Cβ atoms of the threonyl moiety and breakage of the ester bond. This step requires the hydrogen-bond interaction between His-228 and the quinupristin–phenylglycine carbonyl group, which draws electrons away from the ester bond, thereby weakening it and facilitating breakage. Upon completion of the reaction His-270 regenerates by donating its proton to either the carboxylic acid group of the leaving product or water. This proposed reaction mechanism rationalizes the requirement for a divalent cation (11) and the mutagenesis data for Tyr-18, Glu-268, and Glu-284, as these elements all serve to lower the pKa of the quinupristin–threonyl α-proton. Furthermore, the requirement of His-270 is readily explained, as it functions as the catalytic base in the proposed mechanism. Finally, the mutagenesis data for His-228 are clarified by this residue's critical role in ester bond breakage after deprotonation.

The reaction catalyzed by Vgb classifies this enzyme as an intramolecular C O lyase. To date, structural studies of these enzymes have been sparse, the only other being muconate-lactonizing enzymes (15–17). Muconate-lactonzing enzymes catalyze reactions with similar chemistry to that of Vgb, but reactions proceed in the opposite direction (cyclization). Three structurally unrelated classes of muconate-lactonizing enzymes have been identified, where intriguingly one of these classes possesses the seven-bladed β-propeller fold (16). Comparison between Vgb and muconate-lactonizing enzymes reveals that there are several common themes in the structural basis for how these enzyme catalyze their reactions, but also some surprising differences. As outlined above, the two main steps in the Vgb C

O lyase. To date, structural studies of these enzymes have been sparse, the only other being muconate-lactonizing enzymes (15–17). Muconate-lactonzing enzymes catalyze reactions with similar chemistry to that of Vgb, but reactions proceed in the opposite direction (cyclization). Three structurally unrelated classes of muconate-lactonizing enzymes have been identified, where intriguingly one of these classes possesses the seven-bladed β-propeller fold (16). Comparison between Vgb and muconate-lactonizing enzymes reveals that there are several common themes in the structural basis for how these enzyme catalyze their reactions, but also some surprising differences. As outlined above, the two main steps in the Vgb C O lyase reaction are deprotonation facilitated by lowering the pKa of the α-proton and double-bond formation accompanied by ester-bond breakage. In the muconate-lactonizing enzymes these same two steps are present, albeit in reverse order. Similar to the role of Tyr-18 in Vgb, all three classes of muconate-lactonizing enzymes lower the pKa of the proton to be abstracted through hydrogen-bond formation with an adjacent carbonyl group, although different residues are used (15–17). One of the classes also uses a metal ion for decreasing the pKa of that proton (15). However, remote action of the metal ion via a conjugated system and the weakening of the C

O lyase reaction are deprotonation facilitated by lowering the pKa of the α-proton and double-bond formation accompanied by ester-bond breakage. In the muconate-lactonizing enzymes these same two steps are present, albeit in reverse order. Similar to the role of Tyr-18 in Vgb, all three classes of muconate-lactonizing enzymes lower the pKa of the proton to be abstracted through hydrogen-bond formation with an adjacent carbonyl group, although different residues are used (15–17). One of the classes also uses a metal ion for decreasing the pKa of that proton (15). However, remote action of the metal ion via a conjugated system and the weakening of the C H bond from two different sides are unique to Vgb. As to the identity of the catalytic base, Vgb is not exceptional in using a histidine as the β-propeller muconate-lactonizing enzyme also uses this residue (16). In fact, the histidines are located in the same position on strand A, although on different blades. It should be noted that histidines frequently occur at that position within blades of β-propeller proteins (e.g., Protein Data Bank ID codes 1QBI, 1K8K, and 1AOF). As to the double-bond formation and bond breakage step, Vgb is different from the muconate-lactonizing enzymes, as these enzymes appear not to facilitate this step, presumably because of the difference in the nature of the substrates.

H bond from two different sides are unique to Vgb. As to the identity of the catalytic base, Vgb is not exceptional in using a histidine as the β-propeller muconate-lactonizing enzyme also uses this residue (16). In fact, the histidines are located in the same position on strand A, although on different blades. It should be noted that histidines frequently occur at that position within blades of β-propeller proteins (e.g., Protein Data Bank ID codes 1QBI, 1K8K, and 1AOF). As to the double-bond formation and bond breakage step, Vgb is different from the muconate-lactonizing enzymes, as these enzymes appear not to facilitate this step, presumably because of the difference in the nature of the substrates.

The substrate spectrum for Vgb from S. aureus has not yet been extensively examined; however, the manner in which quinupristin is bound to the enzyme can readily explain how Vgb most likely linearizes many naturally occurring type B streptogramins and the clinically relevant semisynthetic variants thereof. The vast majority of type B streptogramins, which include all of those that are medically important, are cyclic hexa-depsipeptides. For these streptogramins there are four known variable sites, of which the group adjacent to phenylglycyl (the 4-oxo pipecolic acid derivative group in quinupristin) displays the most functionalization (18). In the substrate-bound complex structure, these four sites are either pointing into the solvent and are not involved in interactions with the enzyme or are located near the rim of the depression such that alterations can be easily accommodated without compromising affinity or affecting the enzymes ability to break the ester bond between the invariant phenylglycyl and threonyl moieties. For the nonhexa-depsipeptide type B streptogramins (e.g., the hepta-depsipeptide antibiotic etamycin), Bateman et al. (19) have shown that a Vgb from Streptomyces lividans is capable of detoxifying these antibiotics.

Antibiotic Binding by Vgb and the Ribosome.

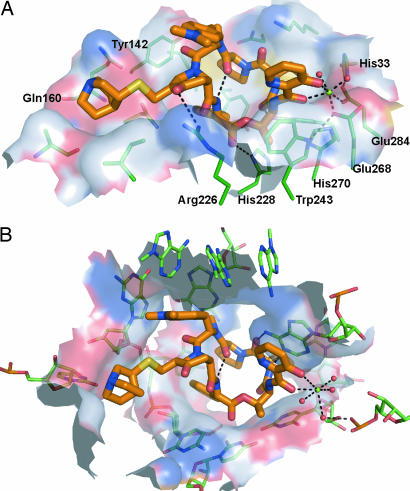

The crystal structure of the bacterial 50S ribosomal subunit in complex with quinupristin at 2.9-Å resolution has provided a detailed view of the mechanism of action for type B streptogramin antibiotics (4). The structural data presented here reveal the enzymatic mechanisms by which resistant bacteria are able to counteract the effects of type B streptogramins and provide the valuable opportunity to examine and compare the features of antibiotic binding by both the natural target and the resistance factor.

When comparing the binding of quinupristin to Vgb versus the 50S ribosomal subunit, the first comment to be made is that the conformation of the drug is essentially identical in both environments (Fig. 3). This finding is not surprising as type B streptogramins are effectively rigid molecules, because of an intramolecular hydrogen bond that constrains the conformation of the cyclic structure. In both the ribosome and the resistance factor, quinupristin forms extensive interactions with its partner, i.e., >60% of its surface becomes buried upon binding. When examining the nature of these interactions, van der Waals forces are identified as the predominant contributor. The quinupristin moieties involved in these van der Waals interactions are similar, but not identical, between Vgb and the 50S ribosomal subunit, with two noteworthy exceptions being the p-dimethylamino-phenylalaninyl group and the 4-oxo pipecolic acid derivative that only show significant interactions in the ribosome and Vgb, respectively (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, hydrogen-bond interactions play only a minor role in antibiotic binding. Quinupristin has a total of 11 hydrogen-bond acceptor/donor groups that can potentially participate in interactions with other biological macromolecules. However, Vgb exploits merely three of these groups for hydrogen-bond interactions, whereas the ribosome only uses two hydrogen-bond acceptor/donor groups. It is noteworthy that Vgb and the 50S ribosomal subunit use different groups on quinupristin for hydrogen-bond interactions, which is unlike what has been observed for aminoglycoside antibiotics where the antibiotic resistance factor APH(3′)-IIIa closely mimics the hydrogen-bond interactions of the ribosome for drug interactions (20). Finally, an important contact observed in the ribosome is a stacking interaction between A2103 of the 23S rRNA and the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety. In Vgb, this contact is partially mimicked by Trp-243; however, here the two aromatic ring systems are not coplanar, thus preventing π–π interactions.

Fig. 3.

Comparison between quinupristin binding to Vgb and the ribosome. (A) Shown is the surface of Vgb within 5.5 Å of the bound streptogramin. The surface is colored according to the identity of the associated atoms: N, blue; O, red; C, white; S, yellow. Also shown are residues that contribute significantly to the surface, as well as Mg2+ and the coordinated water molecules. (B) Identical diagram for the 50S ribosomal subunit (Protein Data Bank ID code 1YJW). The view in both images is such that the orientation of the quinupristin matches in the two complexes (rmsd for all quinupristin ring atoms is 0.22 Å).

The catalytically important Mg2+ ion, which is coordinated by quinupristin in the substrate-bound Vgb complex, is also present in the 2.9-Å resolution structure of the 50S ribosomal subunit (4). In the ribosome structure, Mg2+ is similarly coordinated to the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety, but the remaining four ligands are provided by solvent molecules. In retrospect, the similarities in Mg2+ coordination are not surprising as type B streptogramins can chelate divalent metal ions. Also, the Mg2+ mode of binding involving the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety had been correctly predicted based on spectroscopic analyses more than a decade ago (21). However, what is surprising is that the intrinsic chelating properties of type B streptogramins make these antibiotics inherently susceptible to enzymatic degradation as the metal ion weakens the threonyl Cα–H bond.

Implications for Strategies to Circumvent Vgb Resistance.

The structure of Vgb and the elucidation of its mechanism of streptogramin B inactivation can be exploited for developing strategies to counteract antibiotic resistance. In principle, two avenues are available to overcome bacterial resistance to streptogramins mediated by Vgb: inhibition of the enzyme or alteration of the antibiotic so as to prevent degradation (22). Our initial attempts to develop inhibitors of Vgb, in the absence of structural data, by exploiting a minimal substrate in which the ester bond to be broken was altered into an isosteric amide bond, failed (23). Examination of the Vgb structure suggests that development of a Vgb inhibitor may indeed not be trivial. The reason for this is that binding is predominantly mediated through weak van der Waals interactions, mandating an inhibitor with a large surface area (e.g., <800 Å2), which implies a molecular weight of >600 Da. Possibly a more viable strategy for circumventing resistance mediated by Vgb is altering type B streptogramins so as to reduce the affinity to Vgb without affecting binding to the ribosome. There is a rich literature on the synthesis of type B streptogramin variants using diverse strategies including synthetic (24), semisynthetic (25), chemoenzymatic (23, 26), and solid-phase synthesis approaches (27). The analysis presented here on the similarities and differences between the binding of quinupristin to Vgb vs. the natural target can guide which alterations may reduce the drugs' susceptibility to bacterial resistance. Specifically, moieties of quinupristin that interact with the floor of the depression on Vgb are prime targets for modification, as these could abrogate Vgb degradation while not increasing susceptibility to other mechanisms of resistance such as ribosomal methylation.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis and Protein Production.

Construction of the expression system for Vgb has been reported (11). Site-directed mutants of Vgb were prepared by using the QuikChange method (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Positive clones were sequenced at the Central Facility of the Institute for Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, McMaster University. Protein production and purification for wild-type and mutant proteins followed procedures very similar to those described in ref. 11. For selenomethionyl-substituted Vgb the protein production was modified by using M9 media with l-selenomethionine, l-lysine, l-threonine, and l-phenylalanine and supplementing buffers with 10 mM DTT. Protein purity was assessed by silver-stained SDS/PAGE, and for selenomethionyl-substituted protein selenium incorporation was assessed by mass spectrometry.

Crystallization and X-Ray Data Collection.

Protein at a concentration of 10–20 mg/ml in 50 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) was used for crystallization experiments. Crystals for selenomethionyl-substituted Vgb (VgbSe-Met) were obtained by sitting drop vapor diffusion against a reservoir containing 100 mM phosphate citrate buffer (pH 4.2), 15% PEG 8000, 10–17% PEG 500MME, and 175 mM NaCl. Crystals of wild-type Vgb (VgbWT) were obtained by hanging drop vapor diffusion against a reservoir containing 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.6) and 25% PEG4000. In addition, the protein solution could contain 3 mM MgCl and/or 3 mM quinupristin (or analogs thereof), without impacting crystallization. For obtaining crystals of Vgb in the presence of substrate and Mg2+, the inactive Vgb variant H270A, further modified by a loop alteration (51–56 PLPTPD to ELPNKG) was used (VgbI+L). The protein solution was supplemented with Synercid (3 mM dalfopristin and 1 mM quinupristin; a gift from Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ), and 3 mM MgCl2 dissolved in ethanol with a final concentration of 4.4% ethanol. Crystals for substrate-bound VgbI+L (VgbI+L·quin·Mg2+) were grown by hanging drop vapor diffusion using as reservoir solution 100 mM MES buffer (pH 6.5) and 20% PEG 10000.

X-ray diffraction data for VgbSe-Met (three wavelengths) and VgbWT crystals were collected on the X8C beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY. Diffraction data for VgbI+L·quin·Mg2+ were collected by using a rotating Cu anode generator (Rigaku, Tokyo) augmented with confocal optics (Osmic, Tokyo) and a R-Axis IV++ image plate detector system (Rigaku). All data were measured under cryogenic conditions and processed with HKL2000 software (28) (Table 2 and SI Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of crystallographic data

| Data set | VgbSe-Met* | VgbWT | VgbI+L·quin·Mg2+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | C2 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell parameter, Å, ° | a = 93.0 | a = 73.5 | a = 71.0 |

| b = 34.8 | b = 79.2 | b = 93.7 | |

| c = 86.6 | c = 188.2 | c = 95.3.2 | |

| β = 117.7 | |||

| Wavelength, Å | 0.9000 | 1.0999 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution, Å | 50–1.65 | 50–1.9 | 50–2.8 |

| Completeness, % | 96.7 (78.2) | 98.9 (93.9) | 91.1 (94.1) |

| Redundancy | 7.5 (6.0) | 4.5 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.8) |

| No. of reflections | 29,320 | 86,401 | 14,813 |

| Rsym, % | 3.8 (38.8) | 8.1 (46.1) | 13.6 (31.0) |

| Rfactor/Rfree, % | 15.7/20.5 | 14.4/20.5 | 26.3/31.9 |

| No. protein atoms | 2,312 | 9,337 | 4,548 |

| No. Synercid atoms | — | — | 242 |

| Water/ions | 210/1 | 1,083/5 | 64/4 |

| Bond length, Å | 0.026 | 0.022 | 0.007 |

| Bond angle, ° | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

Data in parentheses represent the outermost shell.

*Statistics are shown for the data set used in refinement (SI Table 3).

Structure Determination and Refinement.

Analysis of the VgbSe-Met diffraction data, using the SnB package, allowed for the identification of four selenium sites, because Met-1 and Met-298 proved to be disordered (29). However, as these selenium sites were located in a single plane perpendicular to the unique axis in the C2 space group, derived protein phases were of exceptionally poor quality. Nonetheless, in combination with density modification techniques, a low-resolution electron density map could be constructed that strongly suggested that Vgb possessed a seven-bladed β-propeller topology. Five homologous superposed seven-bladed β-propeller structures (Protein Data Bank ID codes 1JJU, 1ERJ, 1GXR, 1K8K, and 1CUR) were positioned in the low-resolution electron density map, and their positions and orientations were improved by using a six-dimensional search with BEAST (30). Note that conventional molecular replacement approaches proved ineffective. By subsequently combining the phases derived from multiwavelength anomalous diffraction and the “restricted” molecular replacement approach, an electron density map was calculated in which most of the Vgb structure could be built. The structure was completed by using alternate cycles of reciprocal space refinement and manual model building. The structures for the VgbWT and VgbI+L·quin·Mg2+ were determined by molecular replacement using the program PHASER (31) and the VgbSe-Met structure as a search model. Refinement for all structures was predominantly performed in CNS (32) with the final cycles performed in REFMAC5 (33), and model building was done in PYMOL (34), COOT (35), and O (36) (Table 2). Note that for the VgbWT crystals density corresponding to Mg2+ and/or quinupristin (or analogs thereof) present in the crystallization solutions could never be seen, and this structure is therefore identified as apoenzyme.

Enzyme Assay.

Linearization of quinupristin was monitored by measuring the decrease in fluorescence, resulting from the 3-hydroxypicolinic acid moiety (excitation λmax at 344 nm and emission λmax at 420 nm), using a SpectraMax Gemini Plate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), with 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates (fluorescence compatible). Reactions contained quinupristin, 1 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) and were performed in a final volume of 100 μl. Initial rates were fit to the equation: v = VmaxS/(Km + S). Note, this assay provides greater sensitivity and dynamic range than a previously published absorbance assay (11). Reaction products were analyzed by mass spectrometry to confirm that active Vgb mutants catalyzed the same lyase reaction as VgbWT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present members of the A.M.B. and G.D.W. laboratories for assistance and suggestions and Leon Flaks for assistance during data collection at the National Synchrotron Light Source. This work was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to G.D.W. and A.M.B.). Support for the X8C synchrotron beamline was in part received from the Canadian granting agencies Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M.K. received a scholarship award through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research strategic training program in chemical biology. G.D.W. and A.M.B. hold Canada Research Chairs in Molecular Studies of Antibiotics and Structural Biology, respectively.

Abbreviation

- Vgb

virginiamycin B lyase.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2Z2N, 2Z2O, and 2Z2P).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701809104/DC1.

References

- 1.Eliopoulos GM. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:473–481. doi: 10.1086/367662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocito C. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:145–192. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.2.145-192.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Giambattista M, Chinali G, Cocito C. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:485–507. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tu D, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Cell. 2005;121:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harms JM, Schlünzen F, Fucini P, Bartels H, Yonath A. BMC Biol. 2004;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hershberger E, Donabedian S, Konstantinou K, Zervos MJ. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:92–98. doi: 10.1086/380125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh WS, Ko KS, Song JH, Lee MY, Park S, Peck KR, Lee NY, Kim CK, Lee H, Kim SW, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:5176–5178. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5176-5178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhtar TA, Wright GD. Chem Rev. 2005;105:529–542. doi: 10.1021/cr030110z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehoe LE, Snidwongse J, Courvalin P, Rafferty JB, Murray IA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29963–29970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugantino M, Roderick SL. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2209–2216. doi: 10.1021/bi011991b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukhtar TA, Koteva KP, Hughes DW, Wright GD. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8877–8886. doi: 10.1021/bi0106787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Goffic F, Capmau ML, Abbe J, Cerceau C, Dublanchet A, Duval J. Ann Microbiol (Paris) 1977;128:471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jawad Z, Paoli M. Structure (London) 2002;10:447–454. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pons T, Gomez R, Chinea G, Valencia A. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:505–524. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helin S, Kahn PC, Guha BL, Mallows DG, Goldman A. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:918–941. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kajander T, Merckel MC, Thompson A, Deacon AM, Mazur P, Kozarich JW, Goldman A. Structure (London) 2002;10:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Wang Y, Woolridge EM, Arora V, Petsko GA, Kozarich JW, Ringe D. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10424–10434. doi: 10.1021/bi036205c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonfiglio G, Furneri PM. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 2001;10:185–198. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman KP, Thibault P, Yang K, White RL, Vining LC. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:1057–1063. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199711)32:10<1057::AID-JMS558>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong DH, Berghuis AM. EMBO J. 2002;21:2323–2331. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Giambattista M, Engelborghs Y, Nyssen E, Clays K, Cocito C. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7277–7282. doi: 10.1021/bi00243a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright GD. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1451–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukhtar TA, Koteva KP, Wright GD. Chem Biol. 2005;12:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson JL, Taylor RE, Liotta LA, Bolla ML, Azevedo EV, McAlpine SR. Tetrahdron Lett. 2004;45:2147–2150. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pankuch GA, Kelly LM, Lin G, Bryskier A, Couturier C, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3270–3274. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3270-3274.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahlert C, Sieber SA, Grunewald J, Marahiel MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9571–9580. doi: 10.1021/ja051254t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaginian A, Rosen MC, Binkowski BF, Belshaw PJ. Chemistry. 2004;10:4334–4340. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weeks CM, Miller R. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:492–500. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:1373–1382. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLano WL. PyMOL. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.