Abstract

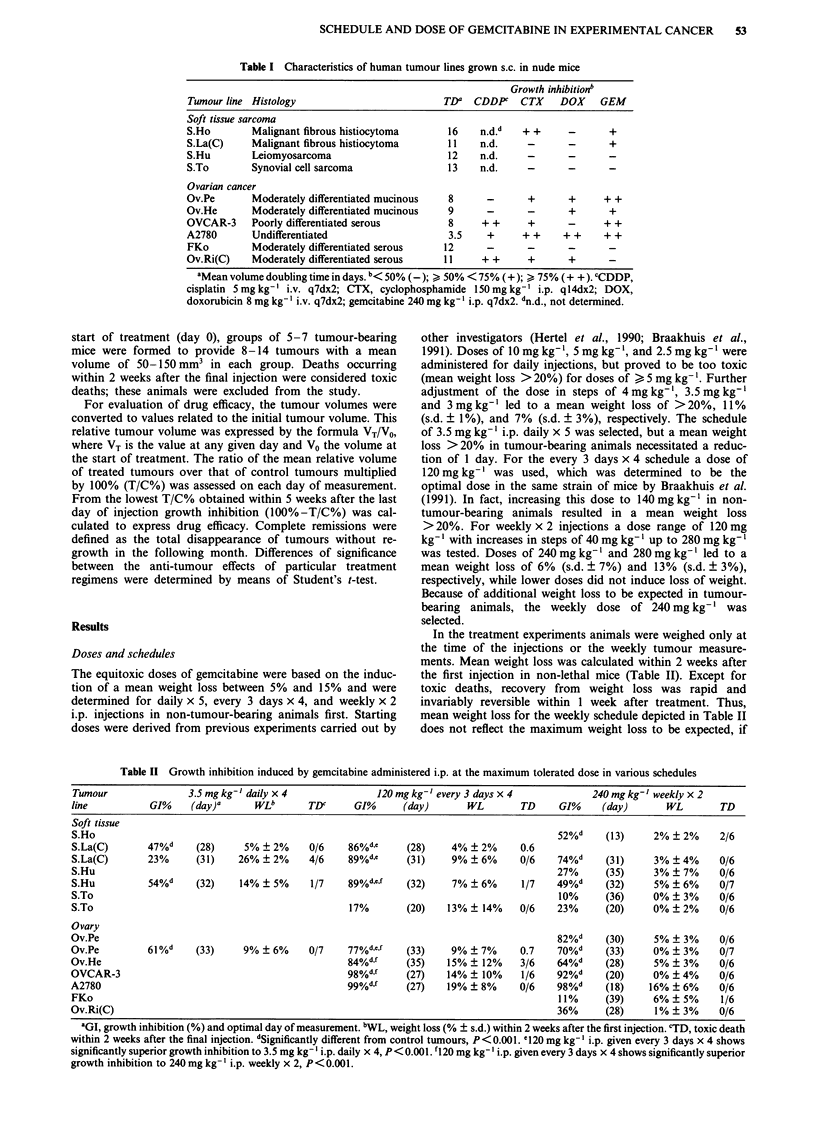

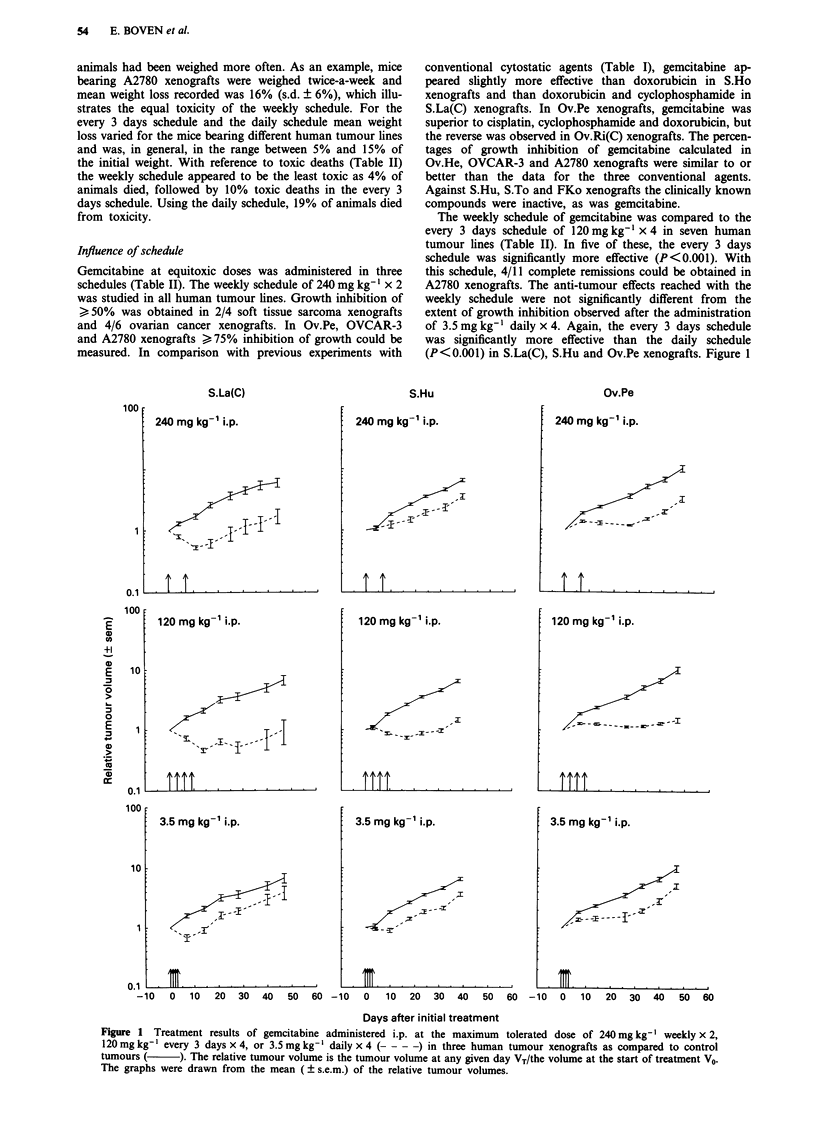

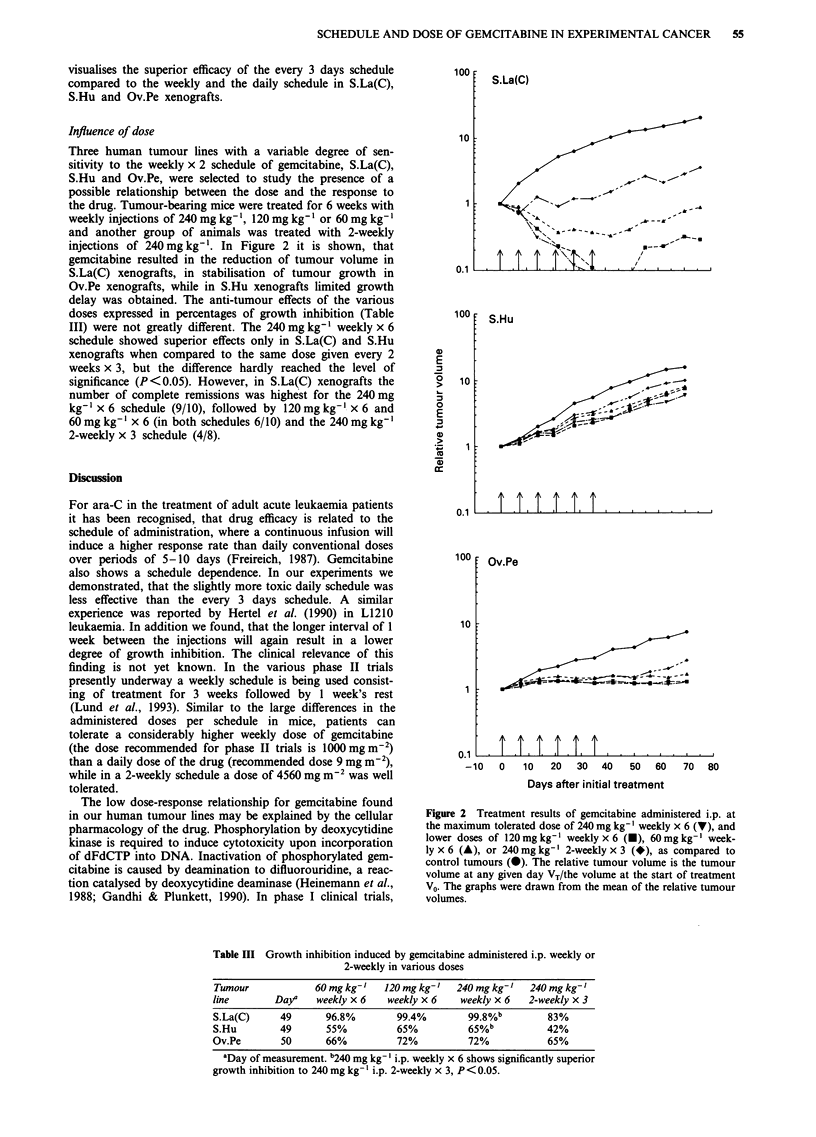

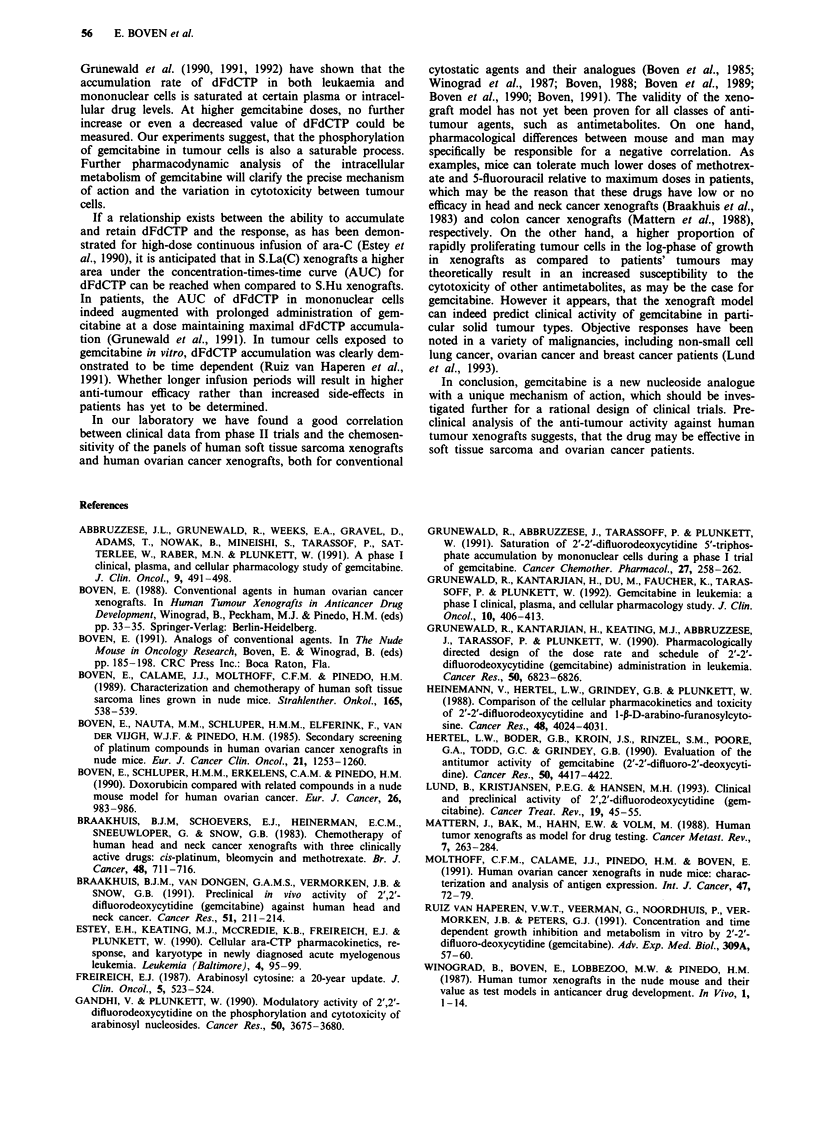

The therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine, a new nucleoside analogue, was assessed in a variety of well-established human soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer xenografts grown s.c. in nude mice. Tumour lines selected had different histological subtypes, growth rates and sensitivities to conventional cytostatic agents. The three different doses and schedules designed on the basis of a mean weight loss between 5% and 15% were i.p. injections of daily 3.5 mg kg-1 x 4, every 3 days 120 mg kg-1 x 4, and weekly 240 mg kg-1 x 2, which ultimately resulted in 19%, 10% and 4% toxic deaths, respectively. The weekly schedule induced > or = 50% growth inhibition in 2/4 soft tissue sarcoma and 4/6 ovarian cancer lines, while in three ovarian cancer lines > or = 75% growth inhibition was obtained. The anti-tumour effects of gemcitabine appeared to be similar or even better than previous data with conventional drugs tested in the same tumour lines. In comparison with the every 3 days schedule, the weekly and the daily schedule were less effective in 5/7 and 3/3 tumour lines (P < 0.001), respectively. In another experiment in three human tumour lines selected for their differential sensitivity to gemcitabine, weekly injections of 240 mg kg-1 x 6 did not result in a significant increase in the percentages of growth inhibition when compared to lower doses of 120 mg kg-1 or 60 mg kg-1 in the same schedule. However, the 240 mg kg-1 weekly x 6 schedule showed superior effects in 2/3 tumour lines in comparison with the same dose given every 2 weeks x 3 (P < 0.05). The preclinical activity of gemcitabine suggests that the drug can induce responses in soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer patients. Our results further indicate that clinical trials of gemcitabine in solid tumour types should be designed on the basis of a schedule rather than a dose dependence.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abbruzzese J. L., Grunewald R., Weeks E. A., Gravel D., Adams T., Nowak B., Mineishi S., Tarassoff P., Satterlee W., Raber M. N. A phase I clinical, plasma, and cellular pharmacology study of gemcitabine. J Clin Oncol. 1991 Mar;9(3):491–498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven E., Calame J. J., Molthoff C. F., Pinedo H. M. Characterization and chemotherapy of human soft tissue sarcoma (STS) lines grown in nude mice. Strahlenther Onkol. 1989 Jul;165(7):538–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven E., Nauta M. M., Schluper H. M., Elferink F., van der Vijgh W. J., Pinedo H. M. Secondary screening of platinum compounds in human ovarian cancer xenografts in nude mice. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1985 Oct;21(10):1253–1260. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(85)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven E., Schlüper H. M., Erkelens C. A., Pinedo H. M. Doxorubicin compared with related compounds in a nude mouse model for human ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1990;26(9):983–986. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90626-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakhuis B. J., Schoevers E. J., Heinerman E. C., Sneeuwloper G., Snow G. B. Chemotherapy of human head and neck cancer xenografts with three clinically active drugs: cis-platinum, bleomycin and methotrexate. Br J Cancer. 1983 Nov;48(5):711–716. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakhuis B. J., van Dongen G. A., Vermorken J. B., Snow G. B. Preclinical in vivo activity of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine (Gemcitabine) against human head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1991 Jan 1;51(1):211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey E. H., Keating M. J., McCredie K. B., Freireich E. J., Plunkett W. Cellular ara-CTP pharmacokinetics, response, and karyotype in newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 1990 Feb;4(2):95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freireich E. J. Arabinosyl cytosine: a 20-year update. J Clin Oncol. 1987 Apr;5(4):523–524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi V., Plunkett W. Modulatory activity of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine on the phosphorylation and cytotoxicity of arabinosyl nucleosides. Cancer Res. 1990 Jun 15;50(12):3675–3680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald R., Abbruzzese J. L., Tarassoff P., Plunkett W. Saturation of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine 5'-triphosphate accumulation by mononuclear cells during a phase I trial of gemcitabine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1991;27(4):258–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00685109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald R., Kantarjian H., Du M., Faucher K., Tarassoff P., Plunkett W. Gemcitabine in leukemia: a phase I clinical, plasma, and cellular pharmacology study. J Clin Oncol. 1992 Mar;10(3):406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald R., Kantarjian H., Keating M. J., Abbruzzese J., Tarassoff P., Plunkett W. Pharmacologically directed design of the dose rate and schedule of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine (Gemcitabine) administration in leukemia. Cancer Res. 1990 Nov 1;50(21):6823–6826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann V., Hertel L. W., Grindey G. B., Plunkett W. Comparison of the cellular pharmacokinetics and toxicity of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine and 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine. Cancer Res. 1988 Jul 15;48(14):4024–4031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel L. W., Boder G. B., Kroin J. S., Rinzel S. M., Poore G. A., Todd G. C., Grindey G. B. Evaluation of the antitumor activity of gemcitabine (2',2'-difluoro-2'-deoxycytidine). Cancer Res. 1990 Jul 15;50(14):4417–4422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund B., Kristjansen P. E., Hansen H. H. Clinical and preclinical activity of 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine (gemcitabine). Cancer Treat Rev. 1993 Jan;19(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(93)90026-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattern J., Bak M., Hahn E. W., Volm M. Human tumor xenografts as model for drug testing. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1988 Nov;7(3):263–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00047755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molthoff C. F., Calame J. J., Pinedo H. M., Boven E. Human ovarian cancer xenografts in nude mice: characterization and analysis of antigen expression. Int J Cancer. 1991 Jan 2;47(1):72–79. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz van Haperen V. W., Veerman G., Noordhuis P., Vermorken J. B., Peters G. J. Concentration and time dependent growth inhibition and metabolism in vitro by 2',2'-difluoro-deoxycytidine (gemcitabine). Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;309A:57–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2638-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winograd B., Boven E., Lobbezoo M. W., Pinedo H. M. Human tumor xenografts in the nude mouse and their value as test models in anticancer drug development (review). In Vivo. 1987 Jan-Feb;1(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]