Abstract

The mammalian focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family of nonreceptor protein-tyrosine kinases have been implicated in controlling a multitude of cellular responses to the engagement of cell surface integrins and G proteincoupled receptors. We describe here a Drosophila melanogaster FAK homologue, DFak56, which maps to band 56D on the right arm of the second chromosome. Fulllength DFak56 cDNA encodes a phosphoprotein of 140 kDa, which shares strong sequence similarity not only with mammalian p125FAKbut also with the more recently described mammalian Pyk2 (also known as CAKβ, RAFTK, FAK2, and CADTK) FAK family member. DFak56 has intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity and is phosphorylated on tyrosine in vivo. As is the case for FAK, tyrosine phosphorylation of DFak56 is increased upon plating Drosophilaembryo cells on extracellular matrix proteins. In situ hybridization and immunofluorescence staining analysis showed that DFak56 is ubiquitously expressed with particularly high levels within the developing central nervous system. We utilized the UAS-GAL4 expression system to express DFak56 and analyze its function in vivo. Overexpression of DFak56 in the wing imaginal disc results in wing blistering in adults, a phenotype also observed with both positionspecific integrin loss of function and position-specific integrin overexpression. Our results imply a role for DFak56 in adhesion-dependent signaling pathways in vivoduring D. melanogasterdevelopment.

In Drosophila melanogaster, as in higher eukaryotes, the extracellular matrix (ECM)1 comprises an interconnected network of glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans, which are secreted and assembled on the cell surface. Cell adhesion to the ECM generates signals important for cell growth, survival, and migration via interactions with integrins, a large family of heterodimeric transmembrane proteins lacking intrinsic enzymatic activity, which in different α/β combinations bind a variety of ECM target proteins. Integrins act not only as simple mediators of cell adhesion but are also involved in the transduction of biochemical signals across the cell membrane and the regulation of cellular functions (1). In a variety of cell types, attachment of integrins to their ligands leads to a profound increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of several cellular proteins, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (2–4). FAK is the founder member of a structurally conserved family of cytoplasmic nonreceptor protein-tyrosine kinases implicated in controlling cellular responses to the engagement of cell surface receptors. This protein-tyrosine kinase (PTK) subfamily so far comprises two mammalian members: FAK and Pyk2 (also known as CAKβ, RAFTK, FAK2, and CADTK) (2–9); they have 45% overall sequence identity, contain a central catalytic domain flanked by large N- and C-terminal domains, and possess a conserved Src SH2 binding autophosphorylation site (FAK = Tyr397; Pyk2 = Tyr402). The FAK N-terminal domain can bind in vitroto the tails of β-integrins (10), and the C-terminal region contains a focal adhesion targeting sequence that localizes FAK to focal adhesions, and binds paxillin and talin (11, 12). A number of cellular stimuli in addition to ECM proteins can induce tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK, including growth factors (13, 14), and this, in combination with direct association of growth factor receptors with integrins (15), provides a linkage between growth control and adhesion. Like FAK, Pyk2 tyrosine phosphorylation can be stimulated by integrin activation (16–18), but this is generally a weak response, and stronger Pyk2 activation is elicited by elevation of intracellular Ca2+levels, particularly in response to activation of G protein-coupled receptors (7, 9, 19–22).

The precise mechanism that links integrin clustering to FAK activation and the role of FAK in integrin-regulated processes during development remains to be determined. However, the importance of FAK during development is clear from genetic studies in mice, in which a knockout of the FAK gene results in embryonic lethality (23). Indeed, both FAK and fibronectin (FN) knockout mice die as a result of similar developmental gastrulation defects, indicating that FAK is able to transduce FN-initiated signals in vivo(23, 24). Mouse fibroblasts from FAK−/− embryos exhibit an increased number of focal contact sites, a rounded morphology and decreased rates of cell migration in vitro(23), suggesting a role for FAK in the process of cell migration. Furthermore, FAK overexpression in CHO cells enhances FN-stimulated cell motility, and this depends upon FAK autophosphorylation at Tyr397(25) and linkages to p130Castyrosine phosphorylation (26). Transient overexpression of the noncatalytic C-terminal domain of FAK, FRNK, inhibits FN-stimulated cell spreading, inhibits the tyrosine phosphorylation of targets such as paxillin (27, 28), and reduces cell migration (29) possibly through displacement of FAK from focal contact sites.

To learn more about the role of the FAK family of PTKs in vivo, we initiated a study in the D. melanogastermodel system. The conserved nature of many receptor signaling systems in Drosophilasuggests that integrin signaling will also be conserved. Drosophilaappears to have a smaller number of integrin genes than vertebrates, with five subunits identified so far (30, 31) of which the best characterized are the position-specific (PS) integrins (32, 33). The myospheroid(mys)gene encodes the βPS subunit (34, 35), the multiple edematous wing(mew)gene encodes the αPS1 integrin subunit (36, 37), and the inflated(if)gene encodes the aPS2 integrin subunit (38–42). These subunits form the PS1 (αPS1βPS) and PS2 (αPS2βPS) integrins, which are essential for the development of both larval and adult flies. In addition to mys, there is a second β-integrin, β-neu, which is expressed in the developing midgut (43). Interestingly, the third identified a-integrin subunit, αPS3/volado,appears to be involved in movement and morphogenesis of tissues during development as well as the signaling events underlying short term memory formation (44, 45).

Using a degenerate PCR approach (46), we have identified a homologue of mammalian FAK, DFak56. DFak56 is a 140-kDa PTK that has strong homology with both FAK and Pyk2. We show that DFak56 is phosphorylated on tyrosine in vivo, and that its phosphotyrosine (Tyr(P)) content is increased when cells are plated on the Drosophilatiggrin ECM component. We have utilized the UAS-GAL4 expression system to study DFak56 in vivo and observed that overexpression of DFak56 results in a range of phenotypes including wing blistering, a developmental phenotype induced by both loss of function and overexpression of the PS integrin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila Stocks

Standard Drosophila husbandry procedures were employed. Flies were raised and crossed at 25°C unless otherwise stated. The wild type strain used was Canton-S. The W1118 strain was used for all microinjections described.

Isolation and Analysis of DFak56 cDNAs

Standard molecular biology protocols were used (47). Degenerate PCR was performed using D. melanogastertudor male and female cDNA as template. The following primers were used 5′, 5′-GGAATTCCAYCGNGAYYTNGCNGCNMG-3′ (HRDLAAR), and 3′, 5′-CCTCGAGAYNCCRWARSWCCANACRTC-3′(DVWS(Y/F)G(I/V)). Sequencing data were collected using the dideoxy chain termination method using 35S-dATP and the Sequenase sequencing kit (U. S. Biochemicals). Sequence was determined on both strands, and the resulting sequence data were compiled using the DNAStar and DNA Strider computer packages (48). Homology searches were performed using the NCBI GenBankTMBLAST programs (49). Screening of D. melanogastertudor male and female libraries constructed in λZAP were performed using clone PE28, a product of the degenerate PCR reaction described above. The excised PE28 cDNA fragment was 32P-labeled and used as probe. Multiple cDNAs were obtained, all of which were sequenced and none of which contained a complete open reading frame. A 5′ fragment of the longest clone was then employed as a probe and resulting positives were isolated and sequenced. A 4106-bp cDNA, clone 8.2, encoding the full DFak56 open reading frame is described and utilized in these studies. This clone contains a 72-bp 5′-untranslated region containing an upstream in-frame stop codon, a 3600-bp open reading frame, and 434 bp of 3′-untranslated sequence. Genomic cosmid clones were isolated by standard techniques from a library containing DNA from the iso-1 line prepared by Tamkun et al. (50). P1 genomic clones (51) were obtained from the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project.

Immunostaining

Wild type embryos were fixed and immunostained (52) with rabbit affinity-purified primary antibodies against DFak56. Immunolocalization was visualized with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG and the avidin DH-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase H complex using diaminobenzidine and H2O2 as substrate (Vector Lab) or fluorescent secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Imaginal discs from wandering third instar larvae were dissected, collected, and rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline prior to fixing in 3.5% paraformal-dehyde for 60 min. Imaginal discs were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies, washed 3 × 10 min in phosphate-buffered saline/0.1% Triton X-100, followed by overnight incubation in secondary antibody at 4 °C, and washed 3 × 10 min in phosphate-buffered saline/0.1% Triton X-100. Imaginal discs were then mounted on polylysine coated coverslips prior to visualization by confocal microscopy.

Generation of Transgenic Flies

DFak56 cDNA was used to generate various P element transformants. The DFak56 transgenes used contained an N-terminally engineered triple hemagglutinin tag that was confirmed by sequencing. The plasmid pUAST:(HA3)DFak56(wild type), was constructed by subcloning the DFak56 cDNA into the pUAST vector (53). P element transformation was performed by microinjection of pUAST:DFak56 together with a delta2.3 transposase containing plasmid into a W1118 D. melanogasterstrain (54, 55). Multiple lines (>4) were obtained. To drive expression of these UAS constructs, several GAL4 enhancer lines were used. P[Engrailed-GAL4] and P[Actin5C-GAL4] inserts were used. In addition, we have used a clonally-inducible GAL4 line that combines the flippase/FRT system and the GAL4/UAS system resulting in the clonal expression of UAS-DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter within wild type tissue. Female flies homozygous for Hsp70-flippase (insertion on the X chromosome) were crossed to males homozygous for both AyGal4 (insertion in the second chromosome) and UAS-GFP (also inserted on the second chromosome). Progeny from this cross were then crossed to homozygous UAS-DFak56 flies, and the resulting larvae were heat shocked for 30 min at 37 °C. Thus, DFak56 expressing clones induced in this system are marked by a UAS-GFP reporter (56).

Anti-DFak56 Antibodies

DNA encoding DFak56 amino acids 881–1200 was subcloned into pGEX-KG to generate a 63-kDa C-terminal GST-DFak56 fusion protein. GST-DFak56 fusion protein was induced and purified from Escherichia coli [BL21(DE3)] bacterial lysates by standard protocols prior to proteolytic cleavage by thrombin. The resulting cleaved DFak56 recombinant protein was used for rabbit immunization. In addition, a peptide encoding the 10 C-terminal amino acids of DFak56 (residues CNTSALHGHA) was synthesized and used for rabbit immunization after coupling to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via the added N-terminal cysteine. Polyclonal antibodies against DFak56 were purified from the serum of rabbit numbers 5946 and 5953 (fusion protein) and numbers 6059 and 6060 (peptide) using a GST-DFak56 fusion protein affinity column. Unless stated otherwise, anti-DFak56 antibodies from rabbit number 5946 were used at 1:2000 dilution for immunoblotting and immunofluorescence analysis. The 4G10 monoclonal antibody was used to detect Tyr(P).

Mammalian Expression Constructs, Site-directed Mutagenesis, and Transient Transfection

For transient transfections, we used the cytomegalovirus-based pcDNA3 mammalian expression vector. The coding sequences of DFak56 and DFak56(K513-R) (amino acids 1–1200) were subcloned into the 5′ Kpn I and 3′ Xba I sites of pcDNA3. The pcDNA3: DFak56(K513-R) mutant of DFak56, in which Lys513in the kinase subdomain II was replaced by Arg, was generated by QuikChangeTMmutagenesis (Stratagene) using oligonucleotides 5′-ATACAAGTGGCGATA-AGGACATGTAAAGCTAAC-3′ and 5′-GTTAGCTTTACATGTCCTTATC-GCCACTTG-3′ and verified by DNA sequencing. Human 293 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate precipitation method. Cells were lysed 36–48 h posttransfection, and the resulting cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and protein kinase assays.

Primary Cell Spreading Assays

Embryos were collected and aged resulting in a 4–6-h-old embryo sample. Embryos were dechorionated in 50% bleach, washed, followed by mild homogenization, filtering, and washing twice in Schneider medium. They were then grown for 24 h at room temperature in Schneider medium supplemented with 20 mIU/ml bovine insulin (Sigma). Good differentiation of these primary cell cultures was observed on tissue culture plates coated overnight with Drosophilalaminin or tiggrin fusion proteins (57). Cells were harvested in 1 ml of RIPA extraction buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50mM NaF, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 μM sodium orthovanadate) and cleared by centrifugation, and protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Equal amounts of protein per sample were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-DFak56 antibodies. For immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting analyses, the immune complexes or proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) and then blotted with primary and secondary antibodies and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Other Methods

Autoradiography was carried out at −70 °C using X-OMAT AR (Kodak). SDS-PAGE was carried out according to Laemmli (58). Protein was determined by the method of Bradford (59). Standard molecular biology techniques were employed for DNA manipulation (47). The 4G10 monoclonal antibody was used to detect Tyr(P) in immunoblotting and immunostaining.

RESULTS

Identification of a Focal Adhesion Kinase Homologue in D. melanogaster, DFak56

To identify novel PTKs in D. melano-gaster, we utilized a degenerate PCR-based approach (Fig. 1A). Highly conserved residues within subdomains VIB and IX of known PTKs were targeted for degenerate PCR primer design (46), and multiple PCR products were obtained, identifying novel as well as previously described D. melanogasterPTKs. These included DSrc28 (60), DSrc41 (61), and DSrc64/Tec29 (62), DER (63), hopscotch (64), and DEK (65) among others. One of the novel PCR products, PE28, displayed most similarity to the mammalian PTKs, FAK, and Pyk2 (2–9)(Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1. Molecular characterization of DFak56.

A, schematic representation of degenerate PCR approach that led to the identification of DFak56. A number of putative novel D. melanogasterPTKs (detailed in text) were identified by degenerate PCR using primers corresponding to conserved residues within kinase domains VIb and IX. Arrowsabove the text indicate the location of the degenerate PCR primers used. B, dendrogram showing phylogenetic relationship between PCR fragments encoding catalytic domains of several D. melanogasterPTKs as well as mammalian FAK family members, HsFAK and HsPyk2. The dendrogram was generated using the Megalign DNAStar program. Cand D, DFak56 amino acid sequence and schematic alignment. C, protein sequence of DFak56. The protein sequence for DFak56 (clone 8.2) is shown. Although not shown here, an in frame upstream STOP codon precedes the initial methionine residue. The termination STOP codon is indicated by an asterisk. The central PTK domain is shaded, and the consensus GXGXXG and AXK in the ATP-binding site is underlined. The kinase insert between kinase subdomains I and II is denoted with a bold underline. The originally identified 64-amino acid PCR clone (PE28) is double underlined. The consensus Src SH2-binding site (Y430AEI), a proline-rich region (PPSKP), and potential Grb2 SH2-binding site (Y956CAT) are shown. D, schematic comparison of DFak56 with the mammalian FAK family kinases, FAK, and Pyk2 displaying regions conserved in mammalian FAK and Pyk2. Structural conservation between DFak56, HsFAK, and HsPyk2 include the presence of a central PTK domain flanked by N- and C-terminal domains, a consensus Src SH2-binding site in the N-terminal region, and two proline-rich regions (PSRPP is not marked). In addition, DFak56 encodes a C-terminal extension of unknown function that is not found in either HsFAK or HsPyk2. E, DFak56 genomic characterization. Top, a map corresponding to the P1 genomic clone DS07982 comprising 85 kb of genomic DNA containing the DFak56 locus is shown. The location of the surrounding P elements is shown by inverted triangles. EcoRI restriction sites are indicated (EI). Sequence-tagged sites (sts)within the region are also indicated (black ovals). Genomic “Tamkun” cosmid clones spanning the DFak56 locus are not shown for simplicity but are available upon request. DFak56 is depicted by the solid black box, and the surrounding genes (A—E)are indicated as gray boxes. The arrowsbelow indicate the orientation of DFak56 and the surrounding genes. A, ribosomal protein L11; B, unidentified EST; C, calpain; D, Hts/adducin; E, tRNA(4Ser)). Bottom, the deduced structure of the approximately 7-kb DFak56 transcription unit is shown in expanded form. The 16 exons are represented by solid black boxes, and thin linesrepresent intron regions. The stop codon preceding the first AUG initiation codon (marked with flag), is indicated by an asterisk, as is the TAA termination codon at the 3′ end of the DFak56 transcript. Two EST sequences, CK1820 and HL01741, encode 3′ DFak56 sequences. CK1820 has been sequenced in its entirety and is therefore indicated as a solid line, the sequence of HL01741 (dashed line)has not been determined.

Multiple cDNAs were obtained using the 204-bp PE28 PCR fragment as a probe for screening D. melanogasteradult cDNA libraries. We have named the locus identified using these resulting cDNAs DFak56 (see below). Fig. 1C shows the complete amino acid sequence of full-length DFak56 cDNA clone 8.2. The DFak56 open reading frame predicts a 1200-amino acid, 135-kDa protein, with greatest similarity to FAK and Pyk2 (34 and 29% overall amino acid identity, respectively; 61 and 53% within the kinase domains) as well as a conserved overall structure (Fig. 1D). DFak56, like FAK and Pyk2, has three domains, a central PTK domain flanked by N- and C-terminal regulatory domains. The kinase domain of DFak56 (Fig. 1C, shaded) contains several sequence motifs conserved among PTKs, including the tripeptide motif DFG that is found in most protein kinases, and a consensus ATP-binding motif GXGXXG followed by an AXKsequence downstream (Fig. 1C, underlined). Interestingly, DFak56 contains a 24-amino acid kinase insert (Fig. 1C, boldand underlined) located between the phosphate anchor-containing kinase subdomain I and kinase subdomain II, a feature not found in either FAK or Pyk2. The N-terminal domain of DFak56 contains a YAEI consensus Src SH2 domain-binding sequence starting at Tyr430(Fig. 1C, boxed), identical to the YAEI motifs in FAK and Pyk2, which bind to the SH2 domain of mammalian Src when phosphorylated. A proline-rich region analogous to the first one in FAK is present in the C-terminal domain (Fig. 1C, boxed). DFak56 Tyr956(Fig. 1C, boxed) aligns with Tyr925in FAK and Tyr881in Pyk2, which are binding sites for the Grb2 SH2/SH3 adaptor protein, but Tyr956lacks the Asn at position +2 needed for Grb2 SH2 domain binding. There is 35% amino acid identity between DFak56 and FAK in the focal adhesion targeting region (11). Interestingly, further C-terminal to this potential focal adhesion targeting domain, DFak56 has a long C-terminal extension, which is absent in mammalian FAK and Pyk2.

DFak56 Maps to 56D5–7

In situ hybridization to polytene chromosomes localized DFak56 to 56D on the second chromosome. Although no evidence exists at this point for another FAK family member in D. melanogaster, we have decided to call this novel FAK homologue DFak56, based on the chromosomal location of its gene, to simplify the literature in the future should one be discovered. Using the in situmapping information, we have confirmed and further defined the genomic localization of DFak56 to region 56D5–7.

In addition to mapping DFak56, we have carried out a careful characterization of this region (Fig. 1E). The data here are derived from P1 genomic sequence data,2our own genomic sequence data from three overlapping cosmids covering the DFak56 locus, DFak56 cDNAs, P element data from this laboratory and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project as well as sequence tag site and EST data.2 DFak56 maps to a 7-kb genomic fragment between sts2767 and sts0326 within P1 DS07982 and to the best of our knowledge at this time comprises 16 exons. Of the multiple DFak56 cDNAs obtained, no alternative splicing events were observed. The region surrounding DFak56contains multiple P element insertions, none of which are within the DFak56gene, the closest being some 5 kb 5′ (l(2)k16914) and <20 bp upstream of the start codon of ribosomal protein L11, (EST A in Fig. 1E) (66). Other transcripts include EST B, encoding an as yet uncharacterized protein, calpain (gene C) (67, 68), Hts/adducin (EST D) (69, 70), and tRNA(4Ser) (EST E) (71). Only 271 bp separate DFak56from EST B on the 5′ side, while just 94 bp separate DFak56from calpain (gene C) at the 3′ side.

DFak56 Encodes a 140-kDa Tyrosine-phosphorylated Protein in Vivo

To determine whether DFak56 has PTK activity, pcDNA3:DFak56 and pcDNA3:DFak56(K513R), in which the conserved Lys in the kinase subdomain II (K513) was mutated to Arg to reduce catalytic activity, were transiently expressed in 293 cells. Anti-DFak56 antibodies (see “Materials and Methods”) were used to immunoprecipitate DFak56 and DFak56-(K513R) from cell lysates. Washed immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting for DFak56. Fig. 2Ashows that DFak56 antibodies specifically recognized a 140-kDa protein (lower panel), which is present when cells were transfected with either pcDNA3:DFak56 or pcDNA3:DFak56(K513R) but not with vector alone (pcDNA3 lanes). Immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by anti-Tyr(P) immunoblotting (Fig. 2A, upper panel). DFak56 was detected as a 140-kDa tyrosine-phosphorylated protein (pcDNA3:DFak56 lanes); mutation of Lys513abrogated tyrosine phosphorylation of DFak56. These results imply that DFak56 is indeed a PTK.

FIG. 2. Biochemical characterization of DFak56.

A, overexpression of DFak56 in 293 cells. 293 cells were transfected in duplicate with cDNAs encoding full-length DFak56 (wild type), DFak56(K513R). Vector DNA alone was used as a control. DFak56 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and anti-Tyr(P) immunoblot (upper panel). In addition, the same blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-DFak56 antibodies (lower panel). B, antibodies raised to the C terminus of DFak56 recognize a 140-kDa protein in S2 cells. Whole cell extract (WCL)from Schneider 2 cells was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and anti-DFak56 immunoblot. Exogenous DFak56, overexpressed in 293 cells, was used as control. C, DFak56 tyrosine phosphorylation is increased on tiggrin plating. Primary cells from 4–6-h-old Drosophilaembryos were plated on either tiggrin or laminin for the indicated times. DFak56 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and anti-Tyr(P) im-munoblot (upper panel). In addition, the same blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-DFak56 antibodies (lower panel).

DFak56 can also be detected as a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in vivo. Anti-DFak56 antibodies recognize a doublet of endogenous DFak56 at 140 kDa from Schneider 2 (S2) tissue culture cells (Fig. 2B, WCL lane). This doublet was observed both by immunoblotting of whole cell lysates and by immuno-precipitation. The upper band comigrated with DFak56 over-expressed in 293 cells and may represent a more highly post-translationally modified DFak56 species (see “Discussion”). Immunoprecipitation of endogenous DFak56 followed by anti-Tyr(P) immunoblotting identified a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of 140 kDa that was confirmed as DFak56 on stripping and reblotting using antibodies to DFak56 (data not shown). Similar results were obtained for whole Drosophilaembryo and third instar extracts as well as for S2 cell extracts (data not shown).

Mammalian FAK has been shown to be tyrosine-phosphoryl-ated in response to plating on FN (2). Therefore, we asked whether DFak56 is tyrosine-phosphorylated under similar circumstances. For this purpose, we plated primary cell cultures prepared from 4–6-h-old Drosophilaembryos on the Drosophila ECM components tiggrin or laminin. After 24 h multiple cell types differentiated, including muscles and neurites, as described previously (57). These differentiated primary cell cultures were lysed in RIPA buffer, and the endogenous DFak56 was immunoprecipitated and resolved on SDS-PAGE. Anti-Tyr(P) immunoblotting showed that after 24 h on tiggrin endogenous DFak56 had an increased level of Tyr(P) (Fig. 2C, tiggrin 24 h lanesrelative to tiggrin 3.5 h lane). Very low levels of Tyr(P) in DFak56 were observed before plating (data not shown). Interestingly, differentiation on the ECM protein laminin caused a smaller increase in phosphorylation. We conclude that DFak56 encodes a 140-kDa PTK, which exists in vivoas a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein. Additionally, the increase in Tyr(P) content of DFak56 when cells are plated on the DrosophilaECM protein, tiggrin, is consistent with activation of the DFak56 PTK.

Expression of DFak56 Protein during Development

We have examined the expression of DFak56 protein throughout development. Total lysates from embryonic, first instar, third instar, early pupa, mid/late pupa, and adult developmental stages were analyzed on SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting for DFak56. Levels of DFak56 expression were high during embryonic development, decreased early in larval development, and then were high again at later larval and pupal stages, indicating that DFak56 protein expression is indeed regulated during development (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, DFak56 appeared as a doublet at all stages, although the during later stages of development the upper band was prevalent. Currently, the nature of this doublet is unknown; it may reflect the phosphorylation status of DFak56, although alternative splicing could also be responsible, because this has previously been reported for both FAK and Pyk2 (20,72,73 ). A 4.5-kb DFak56 RNA was detected by Northern blot analysis, and the levels of this RNA paralleled the levels of DFak56 protein during development (data not shown).

FIG. 3. DFak56 expression.

A, DFak56 is developmentally regulated at the protein level. 100 μg of total cellular protein from Drosophilaat various developmental stages were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis, transferred to Immobilon-P membrane, and blotted with DFak56 antiserum. B, DFak56 is expressed at high levels within the developing embryonic central nervous system. DFak56 immunostaining of developing embryos with anti-DFak56 antibodies is shown in brown. Embryo orientation is anterior to left, dorsal up(a–e), and dorsal facing (f–h). (a), cellular blastoderm. At cellularization, DFak56 is concentrated at sites of cell formation in the periphery. (b)and (c), stages 6–10; gastrulation and germ band extension. DFak56 appears to be ubiquitously expressed. Staining can also be observed in the cephalic furrow (b). In (c)the neuroectoderm stains more prominently and midgut primordia staining can be observed. (d), Embryonic stage 13. DFak56 expression is concentrated in the developing central nervous system. Staining can also be seen in the epithelial cells making up the midgut primordium. (e–h), stages 16 and 17. DFak56 is present ubiquitously. Strong expression of DFak56 can be seen in the brain (h)and the ventral nerve cord where longitudinal axon tracts stain particularly strongly (f). Developing fore-/mid- and hindgut structures and the somatic musculature also express DFak56.

Localization of DFak56 in the Developing Embryo

Immunostaining of Drosophilaembryos with affinity-purified anti-DFak56 antibodies showed strong DFak56 expression in the central nervous system (Fig. 3B). Immunostaining of primary cell cultures plated on laminin and tiggrin showed that anti-DFak56 antibodies also stained neurite networks strongly (data not shown). These data are consistent with in situhybridization analysis of DFak56 RNA during development (data not shown), which indicates that DFak56 is widely expressed during embryogenesis with a high level of expression within the developing nervous system. Additionally, in situhybridization analysis of Drosophilaembryos by the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project using the CK1820 EST revealed expression of DFak56 in the central nervous system, embryonic brain, epidermis, nerve cord, and visceral mesoderm,3 correlating with our in situhybridization and immunostaining data.

Analysis of DFak56 by Ectopic Expression; Overexpression of DFak56 Results in Wing Blistering Phenotypes

Because no DFak56 mutants are yet available, we have chosen to examine the role of DFak56 in vivousing the GAL4-UAS system (53). DFak56 cDNA carrying three copies of the hemagglutinin tag was cloned into a P element expression vector under the control of yeast GAL4 upstream activating sequences (UAS) and P element-mediated germline transformation was used to generate UAS:DFak56(wild type) transgenic fly lines.

The Drosophila wing provides an excellent system for the study of morphogenesis in an intact animal. Because the wing is nonessential, manipulations affecting it need not affect viability. In addition, wing morphogenesis is a relatively simple process involving the conversion of a single layered columnar epithelium to a flattened bilayer in which the basal surfaces of the dorsal and ventral epithelia are in close contact. Previous data suggest that integrins function in early signaling processes as well as in adhesion of the dorsal and ventral surfaces (32, 33). Homozygous mys(βintegrin) mutant cell clones induced in the wing disc during larval stages result in wing blisters in which the dorsal and ventral wing epithelia in and around the clone fail to adhere (35,40, 74).

Ectopic expression of DFak56 under the control of the Actin5C promoter driving GAL4 (Actin5C-GAL4) resulted in 100% pupal lethality. Using Engrailed:GAL4, which targets expression to the posterior compartment of the wing (75) to drive DFak56 expression, we observed the formation of wing blisters in the posterior region of the wing at 22 or 25 °C (Fig. 4B). At higher temperatures an increased level of severity and penetrance was observed (data not shown).

FIG. 4. Overexpression of DFak56 results in a wing blistering phenotype.

DFak56 was expressed in the developing wing disc as described. Light micrographs of wings are shown. A, Engrailed-GAL4; W1118 wild type wing structure. Wing veins L1–L5, anterior cross vein (ACV)and posterior wing vein (PCV)are marked. B, Engrailed-GAL4; UAS:DFak56(wild type) wing. Arrowheadmarks blister.

The blistering phenotype associated with the overexpression of DFak56 under the control of the Engrailed promoter is of interest in light of the known phenotype of integrin mutant flies. However, because wing blistering is associated with loss of integrin function in integrin mutants, the blistering observed upon overexpression of DFak56, a putative downstream effector of integrins, is a somewhat unexpected result. Interestingly, however, overexpression of various αPS subunits under the control of the UAS-GAL4 system in the developing wing disc can also lead to blistering (76). Although it is not currently understood why overexpression of integrin subunits causes blisters, this effect has been postulated to be due to increased signaling rather than a loss of mechanical adhesion.

In the case of αPS integrin subunit overexpression, a period during early pupal development has been defined as being particularly sensitive to integrin αPS2 overexpression (76). If overexpression of DFak56 generates wing blisters for the same reason that overexpression of aPS integrin does, then we would expect there to be a similar critical period of DFak56 expression. To test this hypothesis, we have taken advantage of the fact that expression of transgenes using the UAS-GAL4 system is increased at higher temperature. For these experiments we chose a UAS:DFak56(wild type) transgenic line that has a 50% penetrance of wing vein defects but only a 2–5% penetrance of wing blistering at 22 °C. Flies carrying this UAS:DFak56 insertion and Engrailed:Gal4 were raised at 22 °C and subjected to a single 24-h period at 29 °C at specific developmental times from embryo through late pupation. Consistent with the reported effect of αPS integrin subunit overexpression (76), an increase in wing blistering was clearly seen in Engrailed: GAL4-UAS:DFak56(wild type) animals emerging 4 days after the 29 °C heat pulse, with the fraction of animals emerging with blistered wings reaching a peak at 5 days after the 29 °C pulse, corresponding to a 29 °C pulse received during early pupation. Thereafter, the percentage of wing blisters returned to lower levels (Fig. 5A). Constant exposure to 29 °C resulted in a sustained level of wing blisters (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5. Critical period for blisters caused by overexpression of DFak56.

A, animals expressing a DFak56 transgene under the control of the Engrailed-GAL4 enhancer trap (Engrailed-GAL4;UAS: DFak56(wild type#2) were grown at 22 °C, and the cultures were shifted to 29 °C at the time indicated. Eclosing flies were scored for presence of wing blisters. An increased frequency of wing blisters was evident at 4 days from the end of the 29 °C pulse, reaching a maximum at 5 days and returning to low levels by day 7. Continuous development at 22 °C yields frequencies of 2–5% wing blisters in this genetic background. B, control experiment showing the same culture (Engrailed-GAL4;UAS:DFak56(wild type#2)) grown at 22 °C and then shifted to 29 °C until eclosion. An increased frequency of wing blisters was observed at 3 days from the end of the 29 °C pulse, and the frequency remained high until day 7.

Clonal Overexpression

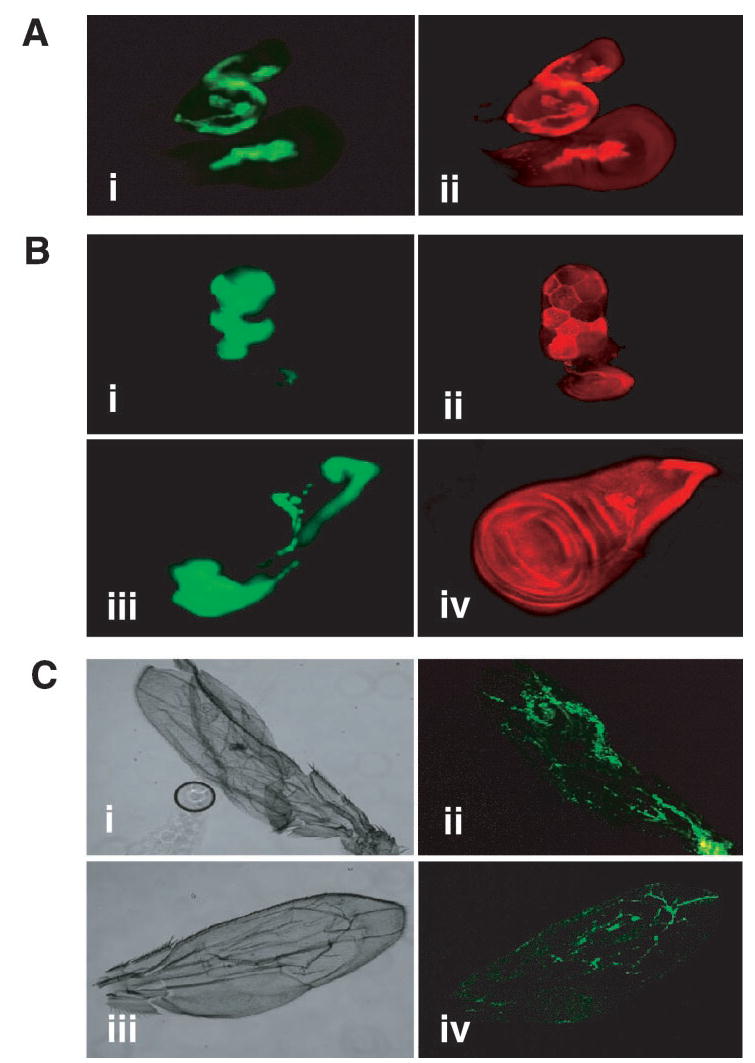

Because the engrailed promoter expresses broadly in the posterior wing, the blistering caused by DFak56 overexpression could be an indirect effect due to the global expression of DFak56. To determine whether DFak56-induced blistering is a property associated with the regions where DFak56 is overexpressed, we used a combination of the flippase-out system and the GAL4-UAS system (56). In this system a fragment of DNA bracketed by FRT sites and containing transcription stop signals is inserted between the Actin5C promoter and GAL4. Heat shock induction of flippase activity induces recombination in which the transcription stop segment is flipped out, thereby allowing the Actin5C promoter to drive GAL4 expression. This system allows the creation of clones of cells expressing DFak56, which are marked by GFP expression (Fig. 6). Expression of DFak56, as judged by immunostaining, and GFP was coincident (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that the system works for DFak56 and also establishing the specificity of the anti-DFak56 antibodies. Although endogenous DFak56 protein is expressed in the third instar wing disc during normal development, higher levels of DFak56 within overexpressing clones are clearly evident compared with endogenous levels. DFak56 overexpressing clones also displayed increased levels of Tyr(P), consistent with the overexpressed DFak56 being active and phosphorylating proteins in these clones (Fig. 6B). Upon eclosion a number of animals with heat shock-induced DFak56-overexpressing clones also displayed wing blisters (Fig. 6C), consistent with our previous results. Further, the observed wing blisters were found to be GFP-positive, thus confirming that the site of DFak56 expression was coincident with the wing blistering phenotype observed and therefore that DFak56 was responsible for the blistering.

FIG. 6. Clonal overexpression of Dfak56 in the developing wing disc.

A, heat shock-induced clones overexpressing wild type DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter. Panel i, imaginal discs displaying heat shock-induced overexpression clones marked by the overexpression of UAS-GFP. Panel ii, DFak56 immunostaining of imaginal discs with anti-DFak56 antibodies is shown in red. B, heat shock-induced clones overexpressing wild type DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter contain increased levels of Tyr(P). Panel i, third instar salivary glands displaying heat shock-induced overexpression clones marked by the overexpression of UAS-GFP. Panel ii, anti-Tyr(P) immunostaining of the same tissues with 4G10 anti-Tyr(P) antibodies is shown in red. Panel iii, third instar wing disc displaying heat shock-induced overexpression clones marked by the overexpression of UAS-GFP. Panel iv, Anti-Tyr(P) immunostaining of the same wing disc with 4G10 anti-Tyr(P) antibodies is shown in red. C, heat shock-induced clonal overexpression of wild type DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter also results in wing blisters. Panel i, adult wing from an animal carrying heat shock-induced clones overexpressing wild type DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter displaying severe wing blistering. Panel ii, GFP fluorescence of the same wing (shown in green). Panel iii, adult wing from an animal carrying heat shock-induced clones overexpressing wild type DFak56 under the Actin-5C promoter displaying a wing blister. Panel iv, GFP fluorescence of the same wing (shown in green).

DISCUSSION

We describe here DFak56, a novel PTK, which is the first D. melanogaster protein to share strong structural and sequence similarity with the mammalian FAK PTK family members. Indeed, phylogenetic tree analysis suggests that DFak56 forms its own branch among the D. melanogasterPTKs, being more similar to the mammalian FAK and Pyk2 than to other PTKs so far described in Drosophila. DFak56 is also the first invertebrate FAK family PTK to be characterized, although a Caenorhabditis eleganshomologue exists (C30F8).

We have mapped DFak56 to 56D5–7 in the D. melanogaster genome and characterized the surrounding genomic region in detail. We note that this is a very gene dense region. None of the mutations in this region map to the DFak56 gene, nor are there any deficiences covering this region. This may be explained by the fact that one of these genes is a ribosomal protein gene, which are commonly haplo-insufficient. Because no obvious DFak56 mutants currently exist, we are now in the process of actively targeting DFak56 for disruption. Extensive attempts to target DFak56 through local P element mobilization techniques have so far been unsuccessful. In light of the DFak56-induced wing blistering phenotypes described here, it is interesting to note that although several groups have now conducted extensive genetic screens with the purpose of identifying molecules involved in integrin-mediated signaling, no such genes have been identified in 56D (77, 78). Additionally, the effectiveness of these screens has been demonstrated by fact that they have independently identified several common loci in addition to existing PS integrin genes. However, these FRT-based screens (77, 78 ) would not be expected to identify genes that encode products involved not only in integrin adhesion but also involved in cell survival or division, because mutant clones would not be produced. It is quite possible that DFak56 could fall into this category. Until DFak56 mutant alleles are identified, it is not possible to formally prove that DFak56 is essential, and, if essential, whether this is because it is required for integrin-mediated signaling in vivo, although the data presented here are strongly indicative of such a function.

Consistent with a role for DFak56 in integrin-mediated signaling pathways, we have been able to show that it is tyrosine-phosphorylated in vivoin response to primary cell plating on DrosophilaECM components. Primary Drosophilaembryo cells plated on the ECM protein tiggrin, an RGD-containing PS2 ligand in vitro, differentiate into multiple cell types (57), a response that is correlated with the increased tyrosine phos-phorylation of DFak56. The increase in tyrosine phosphorylation is significantly slower than that observed in FAK when mammalian cells are plated onto a suitable ECM protein. This may be due to a difference in the levels of integrin expression and/or the subcellular localization of DFak56 or a fundamental difference in the activation mechanism for DFak56. Our data suggest not only that the regulation of DFak56 occurs at the level of tyrosine phosphorylation but that the expression of this protein is highly regulated throughout the life cycle of Drosophila. Interestingly, we consistently observed a DFak56 doublet in S2 cells, as well as in Drosophilalysates from different developmental stages. Alternative splicing in vivohas been described for both mammalian FAK and Pyk2 (72, 73), and for Pyk2 this alternative splicing has been reported to result in differential binding of Pyk2-associated proteins (73). Although DFak56 may be subject to alternative splicing, we have not yet observed any evidence for this. Preliminary results indicate that phosphorylation of DFak56 may in part be responsible for the slower migration of DFak56 on SDS-PAGE.4

Using the GAL4-UAS system (53), we provide evidence for an involvement of DFak56 in multiple developmental processes. The pupal lethality associated with the ubiquitous expression of DFak56 driven by Actin5C-GAL4 at 22°C is reminiscent of the phenotype associated with tiggrin mutants, which die during pupation and which have been shown to have developmental defects in the larval musculature (79). In the mouse model, both the fibronectin and FAK knock out mice share a very similar lethal phenotype (23, 24), which would be consistent with DFak56 and tiggrin perturbations resulting in similar phenotypes in Drosophila.

The observation the DFak56 overexpression causes wing blistering provides a DFak56 gain-of-function phenotype potentially consistent with a role in cell-cell interaction. But why should overexpression of DFak56 result in an integrin loss-of-function phenotype? Recent data suggest a possible answer to this unexpected result. It has been proposed that there are two distinct phases of integrin function in the wing, divided into distinct prepupal and pupal phases (76). In the early phase integrins serve primarily a signaling function, triggering or directing subsequent morphogenesis. Later, PS integrins provide a mechanical link between the epithelia to resist hydrostatic pressure, especially during the wing expansion. Such a model may help to account for the seemingly paradoxical observation that overexpression of an “adhesion protein” leads to a loss of adhesion; the critical function of PS integrins during the early period, which is most sensitive to overexpression, is now postulated to be regulatory rather than adhesive. This hypothesis is consistent with the data presented here on the overexpression of DFak56, which also leads to the formation of wing blisters. If, indeed, the overexpression of aPS subunits leads to the activation of downstream signaling events, then the overexpression of DFak56, a putative downstream effector, would be expected to have a similar effect. Furthermore, it is interesting that both DFak56 and the αPS2 subunit display a very similar critical early period of sensitivity to overexpression, leading to blister formation. This indicates important roles for DFak56 and integrin-mediated signaling pathways during the multiple morphogenic processes occurring as the Drosophilalarva undergoes pupation.

In conclusion, we have identified a D. melanogasterhomologue of the FAK PTK family, which we have named DFak56. DFak56 encodes a 140-kDa PTK that is widely expressed throughout Drosophiladevelopment, particularly strongly in the developing central nervous system. We show that DFak56 is tyrosine-phosphorylated in vivoand in response to plating on DrosophilaECM components. Dominant gain-of-function alleles of DFak56 cause wing blistering, a phenotype associated with defects in integrin-mediated signaling pathways in D. melanogaster. These results imply a role for DFak56 in adhesion during development in vivo. The identification of this novel FAK PTK in Drosophilawill allow the exploitation of a genetically tractable system to be used to further our understanding of the role of the DFak56 PTK in vivo.Indeed, the dosage-sensitive dominant gain-of-function wing blistering phenotype described here should provide the basis for such powerful genetic approaches in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people: J. Fessler, K. Finley, N. Ghbeish, W. Jiang, M. Kanemitsu, J. Meisenhelder, H. Mon-dala, L. Potter, S. Simon, C. Tsai, and J. Wahlstrom. We are grateful to K. Matthews and T. Laverty for providing P element lines and GAL4-driver lines described in this paper. R. H. P. particularly thanks B. Hallberg for support and advice.

The abbreviations used are

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- PTK

protein-tyrosine kinase

- FN

fibronectin

- PS

position-specific

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- bp

base pair(s)

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- kb

kilobase(s)

- UAS

upstream activating sequences

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

Footnotes

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AF112116.

Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project unpublished data.

Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project/Howard Hughes Medical Institute EST Project, unpublished data.

R. H. Palmer and T. Hunter, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Clark EA, Brugge JS. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan JL, Shalloway D. Nature. 1992;358:690–692. doi: 10.1038/358690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanks SK, Calalb MB, Harper MC, Patel SK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8487–8491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaller MD, Borgman CA, Cobb BS, Vines RR, Reynolds AB, Parsons JT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5192–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avraham S, London R, Fu Y, Ota S, Hiregowdara D, Li J, Jiang S, Pasztor LM, White RA, Groopman JE, Avraham H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27742–27751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herzog H, Nicholl J, Hort YJ, Sutherland GR, Shine J. Genomics. 1996;32:484–486. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lev S, Moreno H, Martinez R, Canoll P, Peles E, Musacchio JM, Plowman GD, Rudy B, Schlessinger J. Nature. 1995;376:737–745. doi: 10.1038/376737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki H, Nagura K, Ishino M, Tobioka H, Kotani K, Sasaki T. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21206–21219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Li X, Marchetto GS, Dy R, Hunter D, Calvo B, Dawson TL, Wilm M, Anderegg RJ, Graves LM, Earp HS. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29993–29998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaller MD, Otey CA, Hildebrand JD, Parsons JT. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1181–1187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Parsons JT. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:993–1005. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildebrand JD, Schaller MD, Parsons JT. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:637–647. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rankin S, Rozengurt E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:704–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zachary I, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19031–19034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneller M, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. EMBO J. 1997;16:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Avraham H, Rogers RA, Raja S, Avraham S. Blood. 1996;88:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma EA, Lou O, Berg NN, Ostergaard HL. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:329–335. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaller MD, Sasaki T. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25319–25325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dikic I, Tokiwa G, Lev S, Courtneidge SA, Schlessinger J. Nature. 1996;383:547–550. doi: 10.1038/383547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X, Hunter D, Morris J, Haskill JS, Earp HS. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9361–9364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Lee JW, Graves LM, Earp HS. EMBO J. 1998;17:2574–2583. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng C, Xing Z, Bian ZC, Guo C, Akbay A, Warner L, Guan JL. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2384–2389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, Nomura S, Fujimoto J, Okada M, Yamamoto T. Nature. 1995;377:539–544. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Development. 1993;119:1079–1091. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cary LA, Chang JF, Guan JL. J Cell Sci. 1996;108:1787–1794. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cary LA, Han DC, Polte TR, Hanks SK, Guan JL. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:211–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson A, Parsons JT. Nature. 1996;380:538–540. doi: 10.1038/380538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson A, Shannon JD, Adams RB, Schaller MD, Parsons JT. Biochem J. 1997;324:141–149. doi: 10.1042/bj3240141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilmore AP, Romer LH. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1209–1224. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown NH. Bioessays. 1993;15:383–390. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gotwals PJ, Paine-Saunders SE, Stark KA, Hynes RO. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:734–739. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brower DL, Wilcox M, Piovant M, Smith RJ, Reger LA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:7485–7489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox M, Brower DL, Smith RJ. Cell. 1981;25:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leptin M, Bogaert T, Lehmann R, Wilcox M. Cell. 1989;56:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKrell AJ, Blumberg B, Haynes SR, Fessler JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:2633–2637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brower DL, Bunch TA, Mukai L, Adamson TE, Wehrli M, Lam S, Friedlander E, Roote CE, Zusman S. Development. 1995;121:1311–1320. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wehrli M, DiAntonio A, Fearnley IM, Smith RJ, Wilcox M. Mech Dev. 1993;43:21–36. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogaert T, Brown N, Wilcox M. Cell. 1987;51:929–940. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brabant MC, Brower DL. Dev Biol. 1993;157:49–59. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brower DL, Jaffe SM. Nature. 1989;342:285–287. doi: 10.1038/342285a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown NH. Development. 1994;120:1221–1231. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilcox M, DiAntonio A, Leptin M. Development. 1989;107:891–897. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yee GH, Hynes RO. Development. 1993;118:845–858. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grotewiel MS, Beck CD, Wu KH, Zhu XR, Davis RL. Nature. 1998;391:455–460. doi: 10.1038/35079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stark KA, Yee GH, Roote CE, Williams EL, Zusman S, Hynes RO. Development. 1997;124:4583–4594. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai C, Lemke G. Neuron. 1991;6:691–704. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marck C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1829–1836. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamkun JW, Deuring R, Scott MP, Kissinger M, Pattatucci AM, Kaufman TC, Kennison JA. Cell. 1992;68:561–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90191-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimmerly W, Stultz K, Lewis S, Lewis K, Lustre V, Romero R, Benke J, Sun D, Shirley G, Martin C, Palazzolo M. Genome Res. 1996;6:414–430. doi: 10.1101/gr.6.5.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel NH. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:445–487. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spradling AC, Rubin GM. Science. 1982;218:341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.6289435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito K, Awano W, Suzuki K, Hiromi Y, Yamamoto D. Development. 1997;124:761–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gullberg D, Fessler LI, Fessler JH. Dev Dyn. 1994;199:116–128. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001990205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bradford MM. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gregory RJ, Kammermeyer KL, Vincent WS, Wadsworth SG. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2119–2127. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.6.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi F, Endo S, Kojima T, Saigo K. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1645–1656. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simon MA, Drees B, Kornberg T, Bishop JM. Cell. 1985;42:831–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schejter ED, Segal D, Glazer L, Shilo BZ. Cell. 1986;46:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Binari R, Perrimon N. Genes Dev. 1994;8:300–312. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.3.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scully AL, McKeown M, Thomas JB. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:337–347. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Larochelle S, Suter B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1261:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00010-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emori Y, Saigo K. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25137–25142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theopold U, Pinter M, Daffre S, Tryselius Y, Friedrich P, Nassel DR, Hultmark D. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:824–834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ding D, Parkhurst SM, Lipshitz HD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2512–2516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yue L, Spradling AC. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2443–2454. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leung J, Sinclair DA, Hayashi S, Tener GM, Grigliatti TA. J Mol Biol. 1991;219:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90560-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burgaya F, Girault JA. Mol Brain Res. 1996;37:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00273-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dikic I, Dikic I, Schlessinger J. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14301–14308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zusman S, Patel-King RS, Ffrench-Constant C, Hynes RO. Development. 1990;108:391–402. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brower DL. EMBO J. 1986;5:2649–2656. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brabant MC, Fristrom D, Bunch TA, Brower DL. Development. 1996;122:3307–3317. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prout M, Damania Z, Soong J, Fristrom D, Fristrom JW. Genetics. 1997;146:275–285. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.1.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Walsh EP, Brown NH. Genetics. 1998;150:791–805. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.2.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bunch TA, Graner MW, Fessler LI, Fessler JH, Schneider KD, Kerschen A, Choy LP, Burgess BW, Brower DL. Development. 1998;125:1679–1689. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fujimoto J, Sawamoto K, Okabe M, Takagi Y, Tezuka T, Yoshikawa S, Ryo H, Okano H, Yamamoto T. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29196–29201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fox GL, Rebay I, Hynes RO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]