Abstract

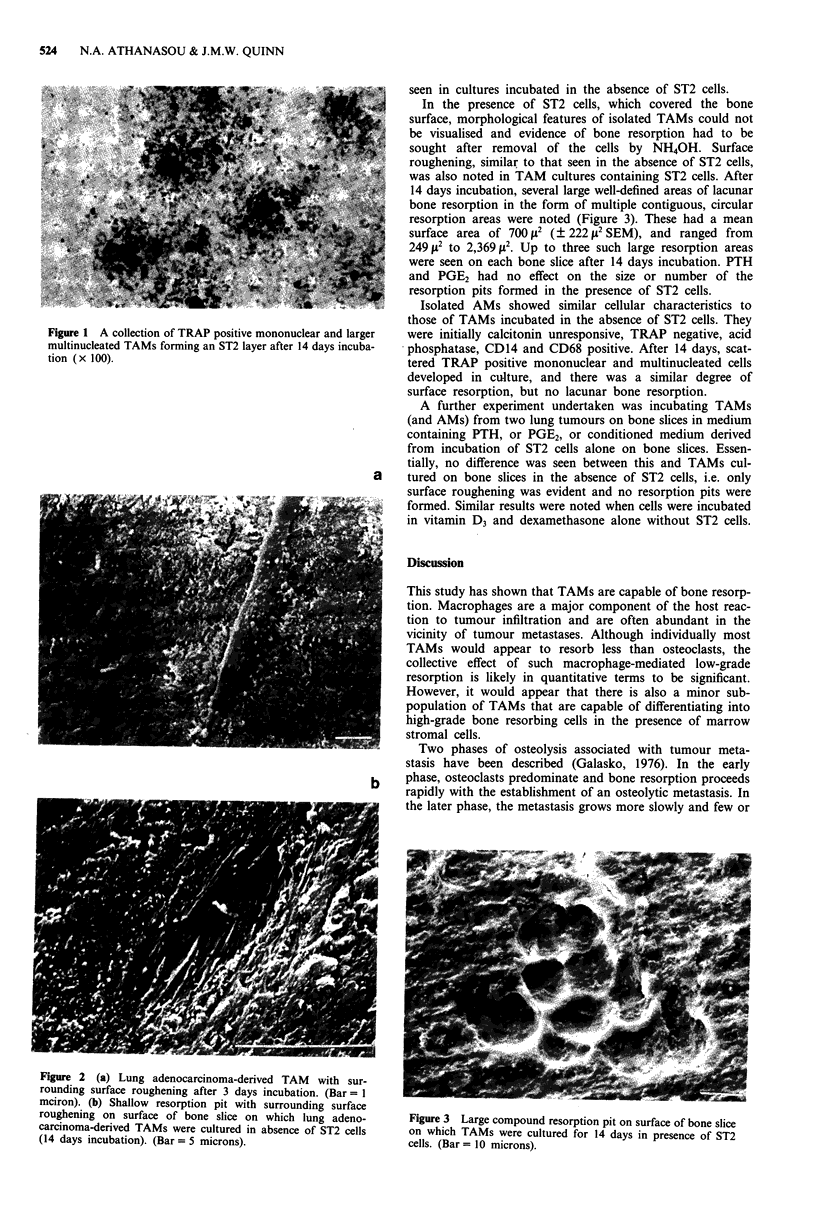

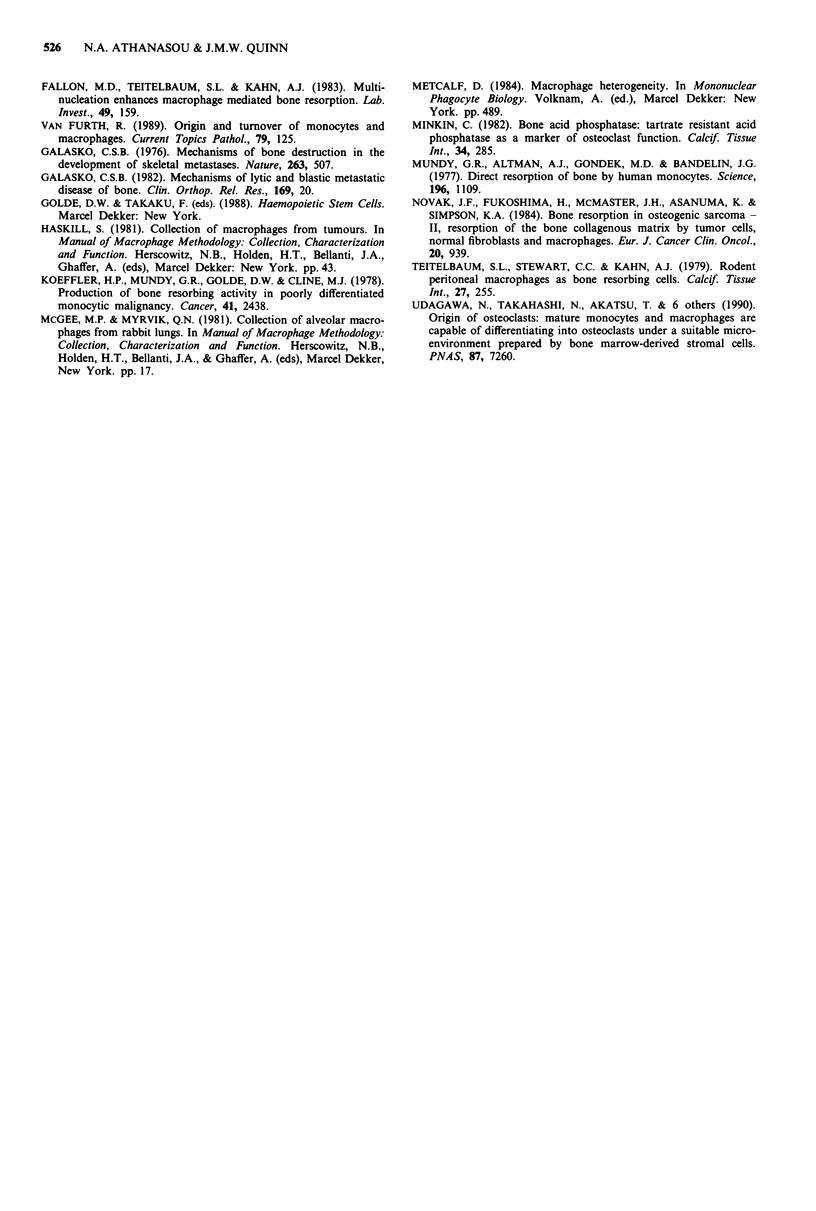

Cellular mechanisms of bone resorption associated with skeletal metastasis are poorly understood. Human tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) isolated from primary lung carcinomas were incubated on bone slices where they formed resorption lacunae after 14 days co-culture with a mouse marrow-derived stromal cell line (ST2) with added 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxy Vitamin D3 and dexamethasone. These co-cultures were associated with the formation of increased numbers of tartrate resistant acid phosphatase positive mononuclear and multinucleated cells. Similar cocultures of ST2 cells with normal alveolar macrophages did not result in lacunar resorption. Both in the presence and absence of ST2 cells, TAMs and normal alveolar macrophages produced roughening of the bone surface with exposure of mineralised collagen fibres. TAMs are capable of both low-grade surface resorption and high-grade lacunar resorption of bone, and a specific interaction with stromal cells is necessary for the latter to occur. TAMs may thus directly contribute to the bone resorption associated with skeletal metastasis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Al-Sumidaie A. M., Leinster S. J., Jenkins S. A. Transformation of blood monocytes to giant cells in vitro from patients with breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1986 Oct;73(10):839–842. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800731026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J., Bulstrode C. J. Resorption of bone by inflammatory cells derived from the joint capsule of hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Jan;74(1):57–62. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J., Ferguson D. J., McGee J. O. Bone resorption by macrophage polykaryons of giant cell tumour of tendon sheath. Br J Cancer. 1991 Apr;63(4):527–533. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J. Immunophenotypic differences between osteoclasts and macrophage polykaryons: immunohistological distinction and implications for osteoclast ontogeny and function. J Clin Pathol. 1990 Dec;43(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.12.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Wells C. A., Quinn J., Ferguson D. P., Heryet A., McGee J. O. The origin and nature of stromal osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells in breast carcinoma: implications for tumour osteolysis and macrophage biology. Br J Cancer. 1989 Apr;59(4):491–498. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers T. J., Magnus C. J. Calcitonin alters behaviour of isolated osteoclasts. J Pathol. 1982 Jan;136(1):27–39. doi: 10.1002/path.1711360104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers T. J., Revell P. A., Fuller K., Athanasou N. A. Resorption of bone by isolated rabbit osteoclasts. J Cell Sci. 1984 Mar;66:383–399. doi: 10.1242/jcs.66.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilon G., Mundy G. R. Direct resorption of bone by human breast cancer cells in vitro. Nature. 1978 Dec 14;276(5689):726–728. doi: 10.1038/276726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon M. D., Teitelbaum S. L., Kahn A. J. Multinucleation enhances macrophage-mediated bone resorption. Lab Invest. 1983 Aug;49(2):159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko C. S. Mechanisms of bone destruction in the development of skeletal metastases. Nature. 1976 Oct 7;263(5577):507–508. doi: 10.1038/263507a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko C. S. Mechanisms of lytic and blastic metastatic disease of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982 Sep;(169):20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeffler H. P., Mundy G. R., Golde D. W., Cline M. J. Production of bone resorbing activity in poorly differentiated monocytic malignancy. Cancer. 1978 Jun;41(6):2438–2443. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2438::aid-cncr2820410651>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkin C. Bone acid phosphatase: tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase as a marker of osteoclast function. Calcif Tissue Int. 1982 May;34(3):285–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02411252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy C. R., Altman A. J., Gondek M. D., Bandelin J. G. Direct resorption of bone by human monocytes. Science. 1977 Jun 3;196(4294):1109–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.16343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J. F., Fukushima H., McMaster J. H., Asanuma K., Simpson K. A. Bone resorption in osteogenic sarcoma--II. Resorption of the bone collagenous matrix by tumor cells, normal fibroblasts and macrophages. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1984 Jul;20(7):939–946. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(84)90168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum S. L., Stewart C. C., Kahn A. J. Rodent peritoneal macrophages as bone resorbing cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1979 Jul 3;27(3):255–261. doi: 10.1007/BF02441194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Tanaka H., Sasaki T., Nishihara T., Koga T., Martin T. J., Suda T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(18):7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Furth R. Origin and turnover of monocytes and macrophages. Curr Top Pathol. 1989;79:125–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]