Abstract

The conceptual basis for many effective language-training programs are based on Skinner's (1957) analysis of verbal behavior. Skinner described several elementary verbal operants including mands, tacts, intraverbals, and echoics. According to Skinner, responses that are the same topography may actually be functionally independent. Previous research has supported Skinner's assertion of functional independence (e.g., Hall & Sundberg, 1987; Lamarre & Holland, 1985), and some research has suggested that specific programming must be incorporated to achieve generalization across verbal operants (e.g., Sigafoos, Reichle, & Doss, 1990). The present study provides further analysis of the independence of verbal operants when teaching language to children with autism and other developmental disabilities. In the current study, 3 participants' vocal responses were first assessed as mands or tacts. Generalization for each verbal operant across alternate conditions was then assessed and subsequent training provided as needed. Results indicated that generalization across verbal operants occurred across some, but not all, vocal responses. These results are discussed relative to the functional independence of verbal operants as described by Skinner.

Keywords: autism, communication training, developmental disabilities, generalization, language, speech, verbal behavior

Impairments in communication are a core feature of autism and other developmental disorders and typically involve a delay or total lack of communicative speech. Although the mechanisms responsible for communication deficits remain unknown, much research has been devoted to both the early identification of language delays and to treatment (e.g., Durand & Crimmins, 1987; Kelley et al., 2007; Lerman et al., 2005; Miguel, Carr, & Michael, 2002; Normand & Knoll, 2006; Sundberg & Partington, 1998; Yoon & Bennett, 2000). Early identification of language delays and intensive behavioral intervention are important for several reasons. First, there is evidence that a lack of early intervention services for children with language delays is associated with an increased risk for difficulties in other adaptive areas (Gillberg, 1991; Venter, Lord, & Schopler, 1993). Second, many problem behaviors, including self-injurious behavior (SIB), aggression, noncompliance, and destructive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2003) are associated with delays in communication (Carr & Durand, 1985). Third, early intervention for language delays may prevent extensive treatments that involve replacing maladaptive behaviors with functional communication skills (e.g., Fisher et al., 1993; Kelley, Lerman, & Van Camp, 2002; Shirley, Iwata, Kahng, Mazaleski, & Lerman, 1997; Wacker et al., 1990; Worsdell, Iwata, Hanley, Thompson, & Kahng, 2000). Therefore, the evaluation of techniques that improve language development appears to be an essential component of intensive early intervention for children with autism and other developmental disabilities.

The conceptual basis for many effective language-training procedures that have received attention both in the literature and in practice is Skinner's (1957) analysis of verbal behavior (e.g., Handleman & Harris, 2001; Leaf & McEachin, 1999; Sundberg & Michael, 2001; Sundberg & Partington, 1998). Lerman et al. (2005) suggested four verbal responses or operants described by Skinner that are relevant for early language training: echoics, tacts, mands, and intraverbals. Each of these verbal operants are occasioned and maintained by specific antecedents and consequences. Echoics are occasioned by a verbal stimulus that is similar in form to the response and are maintained by generalized reinforcement. For example, a therapist may say, “say ‘truck’”; the child responds, “truck”; and the therapist may deliver praise (e.g., “Good job saying truck!”). Tacts are occasioned by a nonverbal stimulus and are also maintained by generalized reinforcement. For example, a therapist may hold up a picture of a dog; the child responds, “dog”; and the therapist may deliver praise (e.g., “Good job saying dog!”). Mands, on the other hand, are occasioned by a motivating operation (Laraway, Snycerski, Michael, & Poling, 2003), such as deprivation of a preferred stimulus, and are maintained by contingent access to a specific consequence. For example, a child may say “juice” after a period of time of not having juice; contingent on the response “juice,” a therapist may provide juice. Finally, intraverbals are occasioned by verbal stimuli that are dissimilar in form to the response and are maintained by generalized reinforcement (like echoics and tacts). For example, a therapist may say, “What's juice for?”; the child may respond, “drinking”; and the therapist may deliver praise (e.g., “Good job answering correctly!”).

Language-training programs may include training for some or all of these verbal operants, partly depending on an individual's existing communication repertoire. For example, if an evaluation of an individual's vocal repertoire suggests that he or she requests desired items but does not label items in the environment, treatment may begin with tact training. However, one consideration while training vocal responses is that topographical units of vocal behavior (e.g., the vocal response “book”) may not be independent of the context in which the response was learned (Kelley et al., 2007; Lerman et al., 2005; Skinner, 1957). For example, tact training may make the vocal response “book” a part of child's repertoire. Subsequently, the presence of a book (antecedent condition) may evoke the response “book,” which is in turn maintained by generalized reinforcement (e.g., praise). However, mastery of this tact response does not ensure that the individual will engage in the vocalization “book” (i.e., manding) when access to a book (specific consequence) would function as reinforcement after a period of deprivation. Thus, a vocal response may be functionally independent under different environmental conditions despite similarity in topography.

Results of several studies provide support for the functional independence of topographically similar verbal operants (Hall & Sundberg, 1987; Reichle, Barrett, Tetlie, & McQuarter, 1987). For example, Lamarre and Holland (1985) taught typically developing preschoolers to mand the abstract responses “on the left” or “on the right” relative to the experimenter's placement of objects; other participants were taught to tact the same topographical responses. Tests of generalization across functional classes (e.g., transfer of the response from either mand to tact or tact to mand) suggested that additional training was required for the participants to engage in the same response form (i.e., same topography) in a different condition (i.e., different function). Thus, these results supported Skinner's (1957) notion of functional independence.

Two additional studies have investigated functional independence of vocalizations in typically developing preschoolers. Petursdottir, Carr, and Michael (2005) assessed the functional independence of mands and tacts using relatively more concrete items (i.e., puzzle pieces and blocks) rather than abstract interpretations (e.g., stating that an item is “on the left”). Results of this study indicated that transfer from mands to tacts and vice versa did occur, although inconsistently. In one of the only studies investigating functional independence of intraverbal skills, Miguel, Petursdottir, and Carr (2005) did not find transfer of responding to intraverbal tasks following multiple-tact training. Others have investigated functional independence of verbal operants with children with developmental disabilities and have also found that transfer from one operant to another when teaching relatively abstract concepts did not emerge without specific instruction (Nuzzolo-Gomez & Greer, 2004; Twyman, 1996). More recently, Lerman et al. (2005) assessed the function of six vocal responses across 4 individuals with disabilities. Each vocal response was exposed to both test and control conditions for four functional operant classes: tact, mand, intraverbal, and echoic (an echoic assessment was conducted for one vocal response for 1 participant). Results for five of six vocal responses suggested that the responses were occasioned and maintained by specific antecedent and consequence conditions. For example, 1 participant engaged in the vocal response “baby” as a tact but did not engage in the response under mand or intraverbal conditions. Kelley et al. (2007) replicated and extended these findings with additional participants and somewhat modified procedures and obtained similar results.

Taken together, the results of previous research support Skinner's (1957) analysis of the functional independence of verbal operants in some populations that may affect how the skills are assessed and taught. However, more research investigating the independence of verbal operants in children with developmental disabilities is warranted given the variable results of previous studies and the relative paucity of research with children with developmental disabilities. In addition, given the ubiquity of language delays in children with developmental disabilities and the need for language training, assessment of the independence of topographically similar responses may aid in language programming. The purpose of the current study was twofold. First, we assessed the functional independence of specific vocalizations. Second, we assessed the conditions under which generalization of verbal operants was likely to occur in 3 participants with developmental disabilities.

Method

Participants and Setting

Three boys who had been diagnosed with developmental disabilities participated in the present study (Steve, Ed, and Tyler). All participants were enrolled in a program specializing in intensive behavioral intervention aimed at improving adaptive and communication skill deficits and were taught in a one-on-one format using discrete-trial instruction. These participants were selected for the study based on language deficits identified by their caregivers or teachers.

Steve was 10 years 10 months old and had been diagnosed with autism. He was observed to emit one-word utterances occasionally. For example, when greeted, he would respond “hi.” In addition, he frequently repeated approximations of vocalizations of others (e.g., attempts at echolalia). Tyler was 3 years 5 months old and had been diagnosed with general language delays. He was observed to emit one- to three-word utterances frequently throughout the day (e.g., “I want cookie,” “hello,” “shoes”). Ed was 3 years 2 months old and had been diagnosed with apraxia. He was observed to emit one-word utterances on a daily basis (e.g., “doggie,” “bubbles”).

Training sessions were conducted at each participant's regular table in the classroom. Sessions were conducted 2 to 5 days per week based on each participant's schedule. During training sessions, other children and therapists were in the classroom but did not interact with the participants. Classrooms contained tables, chairs, bookshelves, toys, and other materials typically found in a classroom setting.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Correct responding was defined on an individual basis for each participant and vocal response. Generally, correct emission of the target vocalization was required across all participants, but approximations of several words were accepted (e.g., “m” was accepted as a correct response for “M&M” for Steve). A correct response was defined as emission of a target vocalization within 5 s of an occasioning stimulus or prompt. Data were collected using paper-and-pencil recording by the therapist who conducted the session. A second independent observer also collected data simultaneously to provide interobserver agreement. Agreement was calculated for each session by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements and disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Agreement for Steve, Ed, and Tyler was 100% and was collected during 25%, 45%, and 29% of sessions, respectively.

Procedure

Pretraining

Highly preferred items were selected for training to increase the likelihood that the vocal response would function as both a tact and a mand. Preference was determined in two ways. For some items (e.g., ship and tricycle), the item was determined as highly preferred based on the amount of time the participant spent engaged with the item during free play. For other items, preference was determined based on the results of paired-choice preference assessments (Fisher et al., 1992) that were conducted periodically as part of ongoing assessment and intervention in the program.

Four to eight items were selected for each participant based on low or zero levels of tact and mand responses during baseline (see below for details). The specific responses and the initial training conditions for each response are shown in Table 1. Prior to training, all targeted words were assessed (and trained, if applicable) as echoics (data available from the second author). Mastery of the target words as echoics prior to training was assessed to develop operational definitions of each vocal response and to ensure that the participants displayed correct emission of each vocal response prior to training other verbal operants.

Table 1.

Item Inclusion, Response Requirement, and Initial Training Condition

| Participant | Item | Response | Condition |

| Steve | Tune | “Tune” | Tact |

| Chocolate | “Choco” | Tact | |

| Book | “Book” | Tact | |

| Ball | “Ball” | Mand | |

| M&M® | “M” | Mand | |

| Cereal puff | “Puff” | Mand | |

| Marshmallow | “Mellow” | Mand | |

| Movie | “Mooie” | Mand | |

| Ed | Skittles® | “Skittles” | Mand |

| Animal cracker | “Animal cracker” | Mand | |

| TV | “TV” | Tact | |

| Shaving cream | “Shaving cream” | Tact | |

| Tyler | Toy dog bone | “Bone” | Mand |

| Fruit snack | “Snack” | Mand | |

| Ship | “Ship” | Tact | |

| Tricycle | “Tricycle” | Tact |

Experimental Design

The effects of mand and tact training on response acquisition were assessed using a multiple baseline across responses design. That is, the effects of tact and mand training were evaluated experimentally by staggering training across responses. Generalization of verbal operants was assessed by conducting posttraining probes (i.e., multiple probe design; Horner & Baer, 1978) for each response.

Verbal Operant Assessment, Training, and Tests for Generalization

Mand Training

Baseline sessions were conducted following a minimum of 5 min of deprivation and consisted of five trials. During baseline, the relevant item was shown to the participant while the therapist simultaneously provided the verbal prompt, “What do you want?” If the participant emitted the target response within 3 s, the therapist provided access to the item. If no response or an incorrect response (defined as any nontargeted vocalization) was emitted within 3 s, the therapist initiated the next trial.

Training sessions consisted of echoic prompting following a minimum of 5 min of deprivation. Each trial began with the therapist showing the item to the participant and asking, “What do you want?” followed immediately by a full vocal prompt (e.g., “ball”). Target responses that were emitted within 3 s of the full vocal prompt produced access to the item until it was consumed or for 20 s. The full vocal prompt was provided for three consecutive trials in which the participant emitted the correct response; the next trial that was presented was followed by a 3-s interval in which the therapist provided the opportunity for the participant to engage in an independent response. If the participant emitted a nontarget or no response during the 3-s interval, the therapist immediately presented the next trial with an immediate vocal prompt. Sessions were terminated after either (a) three consecutive independent occurrences of the target response, (b) a prompted trial following one incorrect independent trial, or (c) 10 total trials had been presented. Thus, session length varied based on responding. The percentage of correct independent responses per session was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses during the independent trials by the number of independent opportunities and multiplied by 100%. Thus, if the participant responded correctly on two of the three independent trials, correct independent responding was 67%.

Tact Training

Baseline consisted of five trials. During baseline, the relevant item was handed to the participant while the therapist simultaneously provided the verbal prompt, “What is it?” Target responses emitted within 3 s of the prompt were followed by praise. If no response or an incorrect response was emitted within 3 s, the therapist began the next trial.

Training sessions consisted of echoic prompting. Each trial began with the therapist handing the item to the child and asking, “What is it?” followed immediately by a full vocal prompt (e.g., “ball”). Contingent on target responses that were emitted within 3 s of the prompt, the therapist removed the target item and delivered praise and access to an alternative preferred item until it was consumed or for 20 s. The full vocal prompt was provided during the first three consecutive trials in which a correct response was emitted. The next trial was followed by a 3-s interval in which an independent response could be emitted. If the participant emitted a nontarget or no response on an independent trial, the therapist immediately presented the next trial with an immediate vocal prompt. Sessions were terminated following either (a) three consecutive independent occurrences of the target response or (b) a prompted trial following an incorrect independent trial. Thus, session length varied based on responses. No more than 10 trials were conducted per session. The percentages of correct independent responses per session were calculated as described above.

Mastery and Generalization Tests

A probe of the baseline condition of the target response was implemented contingent on (a) three of four sessions with 100% correct independent responses and (b) compliance with an unrelated nonverbal imitation distracter task. The purpose of the distracter task was to increase the likelihood of transfer of stimulus control from the vocal prompt to the relevant antecedent condition. Specifically, compliance with an unrelated task prior to a probe trial ensured that the participant's vocal behavior was evoked by the relevant antecedent condition and was not simply a rote response. Contingent on correct responding during the independent probe for two consecutive sessions, the vocalization was considered mastered within the context of that verbal operant.

When a response was mastered under the conditions of one verbal operant, a generalization test (i.e., a test of functional independence of verbal operants) of the response under the conditions of an alternative verbal operant was conducted. Results of previous research suggest that topographical responses occur in a dependent relationship with the context in which they are taught (Kelley et al., 2007; Lamarre & Holland, 1985; Lerman et al., 2005). The purpose of this assessment was to evaluate whether the verbal operants were functionally independent. For example, if “cookie” was taught and mastered under the conditions of a mand, baseline probes were conducted under tact baseline conditions as a test for generalization. If responding occurred at low or zero levels during the generalization tests, the independence of verbal operants hypothesis would be supported. Responding that occurred at mastery levels during the generalization test would suggest that training a topographical response under one set of conditions may generalize to other functions without explicit training. A response was considered generalized if during three consecutive probe sessions independent responding occurred at or above 80% of trials. Contingent on responding below 80% of trials during the generalization test, training was reimplemented in the previously mastered condition, and generalization was again evaluated when the participant again met mastery criteria. If responding remained below mastery criteria during the second generalization test, the target response was selected for treatment under the alternative verbal operant conditions. For example, if a vocalization was mastered as a tact but did not generalize as a mand, mand training was initiated.

Results

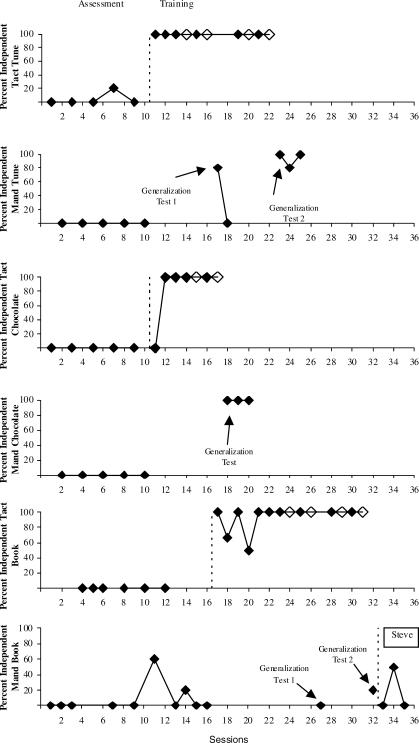

Results of Steve's tact and mand assessment and training are depicted in Figures 1, 2, and 3. Figure 1 depicts the results of the tact assessment and training and mand generalization assessment and training for “tune,” “chocolate,” and “book.” During baseline, Steve engaged in low levels of tacting and manding. Training produced tact responding on 100% of trials for all three responses. In the first mand generalization assessment condition for “tune,” he responded on 80% of trials. However, responding dropped to 0% in the next session. Responding increased to mastery levels in mand probe sessions after additional tact training for “tune.” During mand generalization probes for “chocolate,” Steve engaged in manding on 100% of trials. In contrast to the first two responses, the response “book” did not generalize across verbal operants. In fact, he failed to acquire the mand “book” after training, suggesting that access to the book would not function as reinforcement for the vocal response.

Figure 1.

Steve's percentage of independent responses of the target vocalizations (“tune,” “chocolate,” and “book”) during tact and mand assessment and training. Independent responding prior to a distracter task is depicted by filled diamonds, and independent responding following a distracter task is depicted by open diamonds.

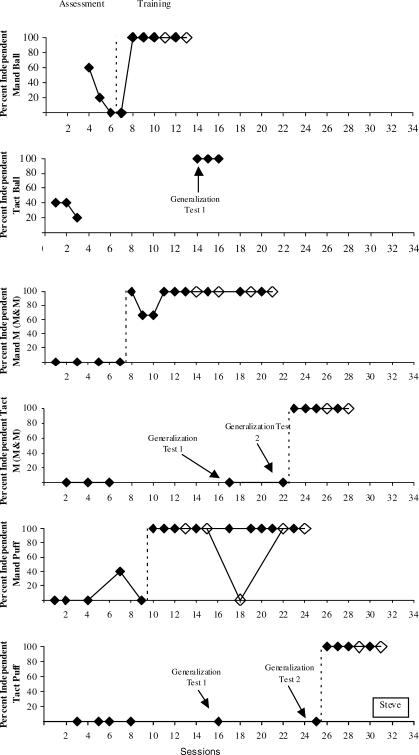

Figure 2.

Steve's percentage of independent responses of the target vocalizations (“ball,” “m,” and “puff”) during tact and mand assessment and training. Independent responding prior to a distracter task is depicted by filled diamonds, and independent responding following a distracter task is depicted by open diamonds.

Figure 3.

Steve's percentage of independent responses of the target vocalizations (“mellow” and “movie”) during tact and mand assessment and training. Independent responding prior to a distracter task is depicted by filled diamonds, and independent responding following a distracter task is depicted by open diamonds.

Figure 2 shows the results of the mand assessment and training and tact generalization assessment and training for “ball,” “m,” and “puff.” During baseline, Steve engaged in moderate to low levels of responding for all vocalizations. Subsequent to mand training, he engaged in manding on 100% of trials for all three operants. When tact generalization tests were conducted, he engaged in tact responses on 100% of trials for “ball.” In contrast, Steve failed to engage in tact responses during test conditions for “m” and “puff.” Thus, tact training was initiated, and Steve tacted correctly on 100% of trials.

Figure 3 depicts Steve's results of the mand assessment and training and tact generalization assessment and training for “mellow” and “movie.” During baseline, he did not mand or tact for these items. Steve acquired the mand “mellow” after training, but the response did not generalize across verbal operants. Thus, tact training was initiated, and Steve acquired the response. After initial mand training for “movie,” he initially acquired the response, but the response failed to generalize to a mand. Despite extensive training, he did not consistently mand for “movie,” indicating that access to the movie would not maintain the response. Steve immediately acquired the tact “movie” when training was initiated.

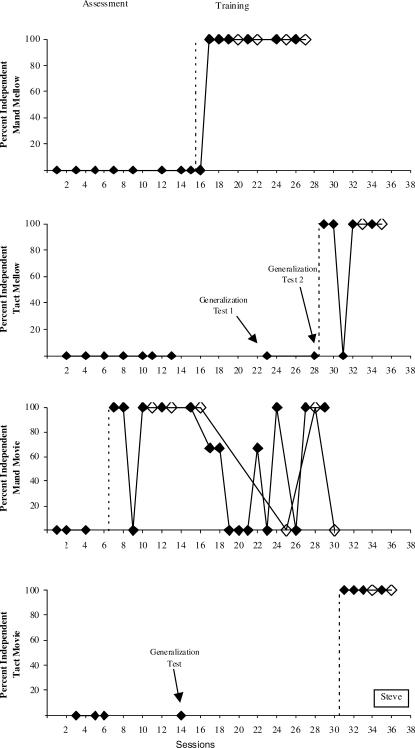

Figure 4 shows Ed's mand assessment and training and tact generalization assessment for “skittles” and “animal cracker.” Ed acquired the mand “skittles” after five sessions of training. He did not engage in the response during the first tact generalization probe. When mand training was reimplemented, he engaged in the response after multiple training sessions. During the second tact generalization probe, Ed engaged in the response on 100% of opportunities. Ed quickly acquired the “animal cracker” response and engaged in high levels of tacting during the generalization probes. Figure 4 also shows the tact assessment and training and mand generalization assessment for “TV” and “shaving cream.” He tacted “TV” on 100% of trials after training was initiated and engaged in manding during generalization probes. Although Ed did not engage in the “shaving cream” response during tact and mand baseline sessions, he began to emit the response under both conditions after training was completed for other responses.

Figure 4.

Ed's percentage of independent responses of the target vocalizations (“skittles,” “animal cracker,” “TV,” and “shaving cream”) during tact and mand assessment and training. Independent responding prior to a distracter task is depicted by filled diamonds, and independent responding following a distracter task is depicted by open diamonds.

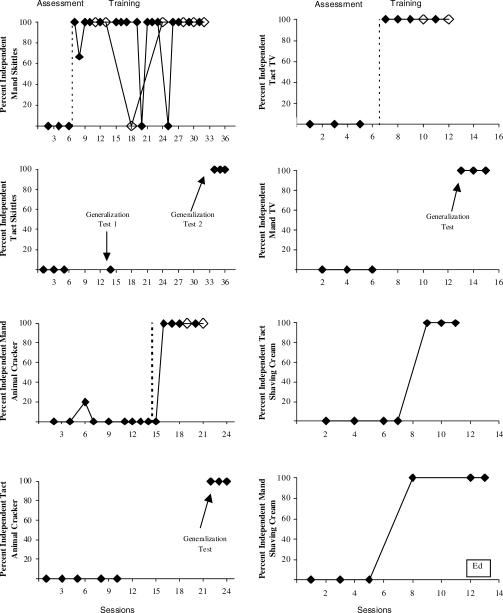

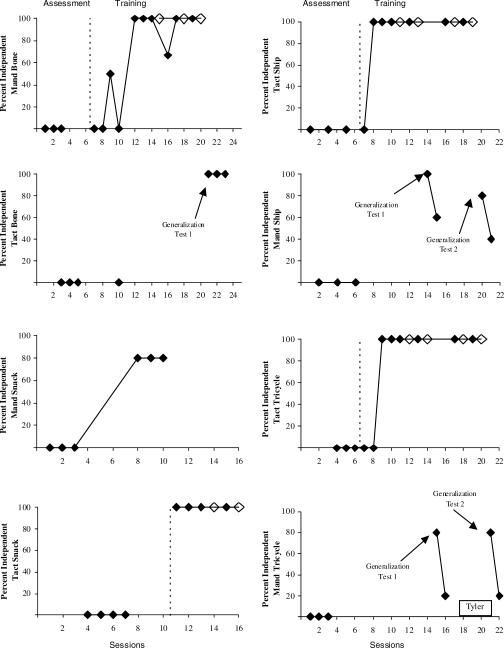

Results for Tyler's tact and mand assessment and training are depicted in Figure 5. The left panels show the results of the mand assessment and training and tact generalization assessment and training for “bone” and “snack.” In baseline, he engaged in no manding or tacting. He acquired the mand “bone” once training was initiated. When tact generalization tests were conducted for “bone,” he engaged in responding on 100% of trials. For “snack,” responding in the mand condition increased in the absence of training. The tact response “snack” was acquired only after being exposed to training. The right panels show the results of the tact assessment and training and mand generalization assessment for “ship” and “tricycle.” Tyler engaged in no tacting or manding in baseline. Once tact training was initiated, tacting increased to 100% of trials for both responses. His responding was similar in both assessments of mand generalization for both “ship” and “tricycle.” He engaged in higher levels of manding during probes after tact training than in baseline. However, he did not engage in mastery levels of either mand response.

Figure 5.

Tyler's percentage of independent responses of the target vocalizations (“bone,” “snack,” “ship,” and “tricycle”) during tact and mand assessment and training. Independent responding prior to a distracter task is depicted by filled diamonds, and independent responding following a distracter task is depicted by open diamonds.

Discussion

We examined the functional independence of topographically similar responses by assessing the extent to which trained vocalizations generalized across verbal operants. For Steve, two of the three trained tact operants generalized to manding, and one of the five trained mand operants generalized to tacting without explicit training. Ed's responding appeared to generalize across operants easily (two mands and one tact generalized across verbal operants). Tyler's responding was similar to Ed's in that three responses generalized across verbal operants. Results of this study support, in part, the functional independence of verbal operants (Kelley et al., 2007; Lamarre & Holland, 1985; Lerman et al., 2005). However, results were idiosyncratic both across and within participants.

The results of the current study, in combination with other studies, highlight the importance of conducting assessments of an individual's vocal repertoire prior to language training (Kelley et al., 2007; Lerman et al., 2005) and during intervention. Although a thorough evaluation of all aspects of the individual's repertoire was not conducted, baseline data indicated that none of the targeted vocalizations were likely to occur as either tacts or mands. After training of a vocal response was initiated, mastery levels were attained for 18 of 19 training opportunities. It is important to note that generalization across verbal operants occurred on 9 of 15 opportunities. Thus, the results of this study suggest that ongoing evaluation of the generalization of the function of a specific vocal response should be a standard part of assessment and training. Specifically, the conditions under which individuals use a particular vocalization should be evaluated subsequent to mastery of a verbal operant. Steve's results provide an example of a case in which generalization should be evaluated every time a vocalization is mastered under the conditions of a specific verbal operant. That is, Steve's vocalizations were likely to generalize from tacts to mands but were unlikely to generalize from mands to tacts. Therefore, careful monitoring of generalization (particularly when training mands first) appears to be an important component for his verbal behavior programming. On the other hand, less frequent monitoring of generalization may be possible for individuals like Tyler and Ed, who were more likely to use a specific vocalization under different conditions subsequent to mastery under conditions of one verbal operant. However, more research is warranted before definitive conclusions may be drawn for these or other individuals due to the limited number of vocalizations assessed.

The results of this study have implications for training verbal behavior for individuals with language delays. Perhaps most significantly, the idiosyncratic results highlight the diverse nature of language deficits and the importance of continuous evaluation of the conditions under which vocal behavior is likely to occur. For example, Steve was more likely than Tyler and Ed to require training for each vocal response. This may have been a function of one of several variables that were not controlled during assessment and training. Specifically, Ed and Tyler may have been exposed to training in the past that increased the likelihood of generalization during this study. Also, Steve differed from Ed and Tyler in two significant ways. First, Steve (10 years old) was older than Ed and Tyler (both 3 years old). Second, Steve had been diagnosed with autism, whereas Ed and Tyler were not. Thus, Steve's age and diagnosis may have influenced the extent to which his responding generalized across verbal operants. Thus, future research may examine the influence of chronological or developmental age and diagnosis on acquisition of verbal behavior and generalization across verbal operants. Also, future research should examine the conditions under which training procedures may be modified to increase the rate of acquisition and the likelihood of generalization.

There are several limitations to the current study that warrant discussion. We assessed 16 vocalizations across 3 participants in the current study. Because the results were somewhat idiosyncratic within and across participants relative to functional independence (i.e., the extent to which vocal responses generalized across verbal operants), further research with additional participants and vocal responses is necessary before more robust conclusions may be drawn about the functional independence of verbal operants. For example, it is possible that as the number of trained operants increases, the number of responses that generalize across verbal operants may increase (i.e., a positive correlation). Second, specific vocal responses were targeted in the current study because they were not currently being used as mands or tacts. It is possible that generalization across verbal operants would have been more likely had we chosen responses that had previously been emitted, even if only occasionally. Finally, we provided only two opportunities for a vocalization to generalize across verbal operants before initiating training under the conditions of an alternate verbal operant. It is possible that additional opportunities for generalization would have produced emergence of the response under different conditions. For example, Steve's mands generalized to tacts on only one of the five opportunities. Additional training under mand conditions may have produced better generalization to the tacts tested, but it would not be clinically appropriate to keep him in training for mands once mastered or to hold off training the tacts when it was apparently needed.

A potentially important area for future research indicated by the results of this study includes analyses of the specific variables that affect generalization across verbal operants. Conceptually, one would expect that generalization across tact and mand operants (or vice versa) would be more likely than across other verbal operants, because the assessment and training for both often contain similar antecedent conditions. For example, training of “juice” as a tact might include a glass of juice and perhaps the prompt, “What is it?” Assessment or training of “juice” as a mand, on the other hand, may include a glass of juice and perhaps the prompt, “What do you want?” (see Bourret, Vollmer, & Rapp, 2004; Kelley et al., 2007; Lerman et al., 2005; for examples of mand assessment or training with impure antecedent conditions). Because the topographies of both verbal operants are identical and the antecedents may include similar stimulus conditions, an individual may engage in a generalized response as a result of poor discrimination of the respective stimulus conditions. Further, other studies could assess the extent to which verbal operants generalize across environments. Another area of future research worthy of additional study is the conditions under which intraverbal behavior may be trained in individuals with limited vocal repertoires. In the current study, we focused on mand and tact assessment and training because of the limitations of the participants' vocal behavior. Thus, future research should assess the utility of introducing intraverbal training concurrent with mand and tact training.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by Grant 5 R01 MH69739-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We thank Henry S. Roane for his valuable comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed. rev.) Washington, DC: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bourret J, Vollmer T.R, Rapp J.T. Evaluation of a vocal mand assessment and vocal mand training procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:129–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr E.G, Durand V.M. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:111–126. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand V.M, Crimmins D.B. Assessment and treatment of psychotic speech in an autistic child. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987;17:17–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01487257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C, Cataldo M, Harrell R, Jefferson G, Conner R. Functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:23–36. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C. Outcome in autism and autistic-like conditions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:375–382. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G, Sundberg M.L. Teaching mands by manipulating conditioned establishing operations. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1987;5:41–53. doi: 10.1007/BF03392819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handleman J.S, Harris S.L. Preschool education programs for children with autism (2nd ed.) Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horner R.D, Baer D.M. Multiple-probe technique: A variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley M.E, Lerman D.C, Van Camp C.M. The effects of competing reinforcement schedules on the acquisition of functional communication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:59–63. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley M.E, Shillingsburg M.A, Castro M.J, Addison L.R, LaRue R.H, Martins M.P. Assessment of the functions of vocal behavior in children with developmental disabilities: A replication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:571–576. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre J, Holland J.G. The functional independence of mands and tacts. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1985;43:5–19. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraway S, Snycerski S, Michael J, Poling A. Motivating operations and terms to describe them: Some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:407–414. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf R, McEachin J, editors. Behavior management strategies and a curriculum for intensive behavioral treatment of autism. New York: DRL Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D.C, Parten M, Addison L.R, Vorndran C.M, Volkert V.M, Kodak T. A methodology for assessing the functions of emerging speech in children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:303–316. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.106-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel C.F, Carr J.E, Michael J. The effects of a stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure on the vocal behavior of children diagnosed with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2002;18:3–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03392967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel C.F, Petursdottir A.I, Carr J.E. The effects of multiple-tact training and receptive-discrimination training on the acquisition of intraverbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:27–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03393008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand M.P, Knoll M.L. The effects of a stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure on the unprompted vocalizations of a young child diagnosed with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF03393028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Greer R.D. Emergence of untaught mands and tacts of novel adjective-object pairs as a function of instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03392995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir A.I, Carr J.E, Michael J. Emergence of mands and tacts of novel objects among preschool children. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:59–74. doi: 10.1007/BF03393010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle J, Barrett C, Tetlie R.R, McQuarter R.J. The effect of prior intervention to establish generalized requesting on the acquisition of object labels. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 1987;3:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley M.J, Iwata B.A, Kahng S, Mazaleski J.L, Lerman D.C. Does functional communication training compete with ongoing contingencies of reinforcement? An analysis during response acquisition and maintenance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:93–104. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigafoos J, Reichle J, Doss S. “Spontaneous” transfer of stimulus control from tact to mand contingencies. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1990;11:165–176. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(90)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Michael J. The benefits of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification. 2001;25:698–724. doi: 10.1177/0145445501255003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Partington J.W. Teaching language to children with autism or other developmental disabilities. Pleasant Hill, CA: Behavior Analysts, Inc; 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twyman J.S. The functional independence of impure mands and tacts of abstract stimulus properties. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1996;13:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Venter A, Lord C, Schopler E. A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;33:489–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D.P, Steege M.W, Northup J, Sasso G, Berg W, Reimers T, et al. A component analysis of functional communication training across three topographies of severe behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:417–429. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsdell A.S, Iwata B.A, Hanley G.P, Thompson R.H, Kahng S. Effects of continuous and intermittent reinforcement for problem behavior during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:167–179. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Bennett G.M. Effects of a stimulus-stimulus pairing procedure on conditioning vocal sounds as reinforcers. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2000;17:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03392957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]