Abstract

Emissive nucleoside analogues that are sensitive to their microenvironment can serve as probes for exploring RNA folding and recognition. We have previously described the synthesis of an environmentally sensitive furan-containing uridine and its triphosphate, and have demonstrated that T7 RNA polymerase recognizes this modified ribonucleoside triphosphate as a substrate in in vitro transcription reactions. Here we report the enzymatic preparation of fluorescently tagged HIV-1 TAR constructs and study their interactions with a Tat peptide. Two extreme labeling protocols are examined, where either all native uridine residues are replaced with the corresponding modified fluorescent analogue, or only key residues are site-specifically modified. For the HIV-1 Tat–TAR system, labeling all native uridine residues resulted in relatively small changes in emission upon increasing concentrations of the Tat peptide. In contrast, when the two bulge U residues were site-specifically labeled, a reasonable fluorescence response was observed upon Tat titration. The scope and limitations of such fluorescently tagged RNA systems are discussed.

1. Introduction

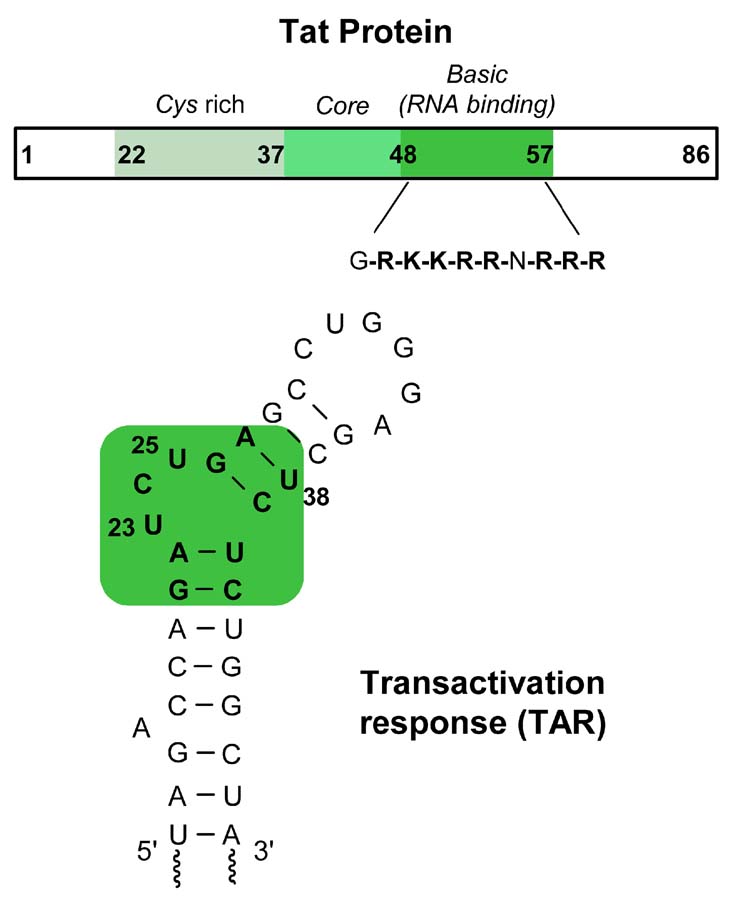

HIV replication relies upon the transcription and translation machineries of its host cell.1,2 In the absence of Tat, a small 86 amino acid viral protein, transcription of viral genes is impaired.3,4 Recruitment of Tat to the transcription machinery via its binding to the cognate RNA site named the transactivating response element (TAR), a 59-residue stem-loop RNA structure located at the 5′ end of all nascent HIV-1 transcripts, substantially facilitates the otherwise poor elongation process (Figure 1). Tat, therefore, is involved in a positive feedback mechanism that ensures high level of HIV transcription.1,4–6 The Tat-TAR interaction has been a subject of numerous structural studies, and has been widely studied as a potential therapeutic target.7–14

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram representing the Tat protein and TAR RNA fragment.

Several tools have been developed to advance the understanding of the Tat–TAR interaction and the discovery of Tat–TAR inhibitors.7,8,15,16 Conventional methods such as gel-mobility shift and filter binding assays have been extensively used in determining the strength and specificity of TAR binding by Tat and Tat derived peptide conjugates. However, these techniques are laborious and the binding affinities obtained are not always a true measure of solution affinities under equilibrium conditions.

In contrast, fluorescence-based methods typically provide researchers with effective tools for examining such biological recognition events, often in real-time and with great sensitivity. In particular, fluorescent nucleoside analogues that are isosteric to natural nucleobases and are sensitive to changes in their microenvironment have found wide applications in biophysics.17–23 Indeed, labeling TAR with 2-aminopurine, an emissive adenosine isoster, has recently been utilized to follow up on ligand binding using steady-state emission spectroscopy.24,25 Similarly, a TAR construct containing benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione, a large U analogue, displayed changes in fluorescence upon Tat binding when incorporated in the U-rich bulge.26

We have recently reported a series of responsive fluorescent pyrimidine nucleoside analogues functionalized at the 5-position with aromatic five-membered heterocycles.27 A furan-containing uridine is particularly useful. It displays emission in the visible range that is sensitive to changes in solvent polarity, being significantly more emissive in polar environment when compared to a non-polar one. We have also demonstrated the effective incorporation of this fluorescent nucleoside analogue into RNA constructs using in vitro transcription reactions, and its use in exploring RNA recognition events such as RNA–antibiotics interactions.28 To illustrate the potential of this fluorescent probe for the study of HIV-1 RNA targets, we describe here the synthesis of fluorescent TAR constructs by transcription reactions and subsequent development of an effective fluorescence-based Tat-TAR binding assay.

2. Results and Discussion

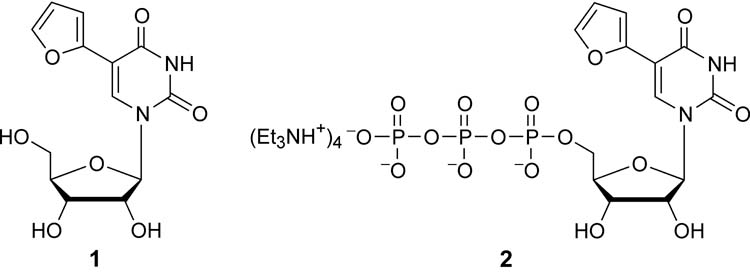

2.1. Triphosphate synthesis and incorporation

We have previously described the synthesis of the furan-containing ribonucleoside 1 and its triphosphate 2 (Figure 2).28 We have also demonstrated that T7 RNA polymerase recognizes this modified ribonucleoside triphosphate as a substrate in run-off in vitro transcription reactions and very efficiently incorporates it into RNA oligonucleotides. We have further illustrated that fluorescent RNA constructs, generated in this fashion, can be employed for the development of biophysical assays. Specifically, we have applied this method for the examination of a fluorescent bacterial A-site and its interactions with aminoglycoside antibiotics.28 Here we employ similar experimental procedures for the preparation of fluorescently tagged TAR constructs as described below.

Figure 2.

Structure of furan-modified ribonucleoside and its triphosphate.

2.2. Assay development

Several options exist when a target RNA sequence is fluorescently tagged. Introducing the reporter nucleotide near the native recognition domain is likely to work best, as long as the recognition properties are not altered. In this particular case, “isomorphic” fluorescent nucleobases have advantages, as the modified RNA constructs are likely to have comparable recognition features to the unmodified RNA targets. In addition, transcription reactions with a modified nucleoside triphosphate replacing its natural counterpart impose certain limitations. Two extreme labeling protocols can be envisioned, where either all native residues are replaced with the corresponding modified fluorescent analogue, or only key residues are site-specifically modified. Here we examine the benefits and disadvantages of both.

2.3. Tat–TAR system

The TAR binding domain of Tat contains six arginine and two lysine residues. Short peptides encompassing this 47–58 arginine-rich motif and the Tat protein show similar binding characteristics.29–31 Although these peptides display somewhat lower binding affinity when compared to the entire Tat protein, they have been extensively employed as model systems due to the protein’s propensity to aggregate.32 Structural analysis indicates that upon binding, the Tat peptide substantially perturbs the conformation of the U-rich bulge in the TAR RNA.33–36 Through mutagenesis, chemical probing and peptide binding studies, U23 located in the bulge was found to be crucial for effective Tat binding, whereas the replacement of C24 and U25 with any other nucleotide does not affect the peptide–RNA recognition.37,38

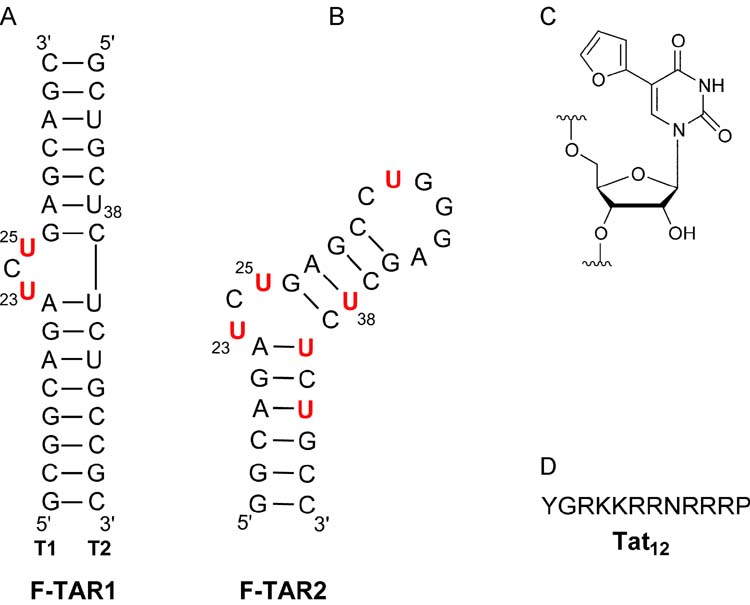

We conjectured that replacing U23 and U25 in the TAR bulge with the environmentally sensitive uridine analogue 1 is likely to signal conformational changes induced upon Tat binding with either enhanced or quenched emission. To compare the utility of a per-labeled fluorescent construct to a site-specifically labeled TAR, two different constructs, F-TAR1 and F-TAR2 were transcribed (Figure 3). Their photophysical properties and their sensitivity to Tat binding were examined as detailed below.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Secondary structure of fluorescently labeled F-TAR1 and F-TAR2 RNA used in this study, respectively. Modifications are highlighted in red. (C) Structure of the fluorescent label. (D) Single-letter amino acid code for the Tat derived peptide used in this study.

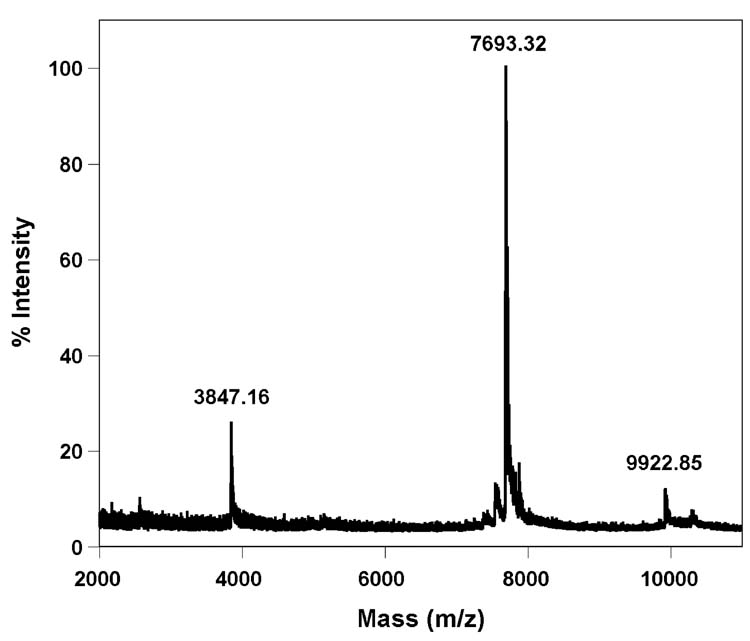

The single stranded 29-mer F-TAR1 was easily synthesized by a transcription reaction in the presence of a DNA template containing the complementary T7 RNA polymerase promoter consensus sequence, and triphosphate 2 replacing UTP. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis confirmed the presence of a full length transcript containing six furan-modified uridines (Figure 4). Thermal denaturation studies with both native and modified F-TAR1 display two transitions in the forward cycle, with the per-modified construct being more stable than the unmodified construct (Figure 5). The first transition (Tm ∼ 51°C) is not affected by the modification, suggesting a possible formation of a bulge-bulge kissing complex. The second transition corresponding to the hairpin-loop structure is substantially altered by the presence of modification as compared to native TAR construct. The enhanced stability (ΔTm ∼ 10°C) suggests that each modified U contributes, on average, about 1.5 °C to the melting temperature, a value which is in agreement with related studies (see below). It is worth noting that the TAR constructs show only a single transition corresponding to the hairpin-loop structure in the reverse thermal denaturation cycle, further supporting the notion that a metastable kissing complex contributes to the lower temperature transition observed in the forward direction.

Figure 4.

MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of furan-labeled F-TAR1 calibrated relative to the +1 and +2 ions of the internal 25-mer DNA standard (m/z: 7693.32 and 3847.16). Calculated mass [M] = 9922.21; observed mass = 9922.85.

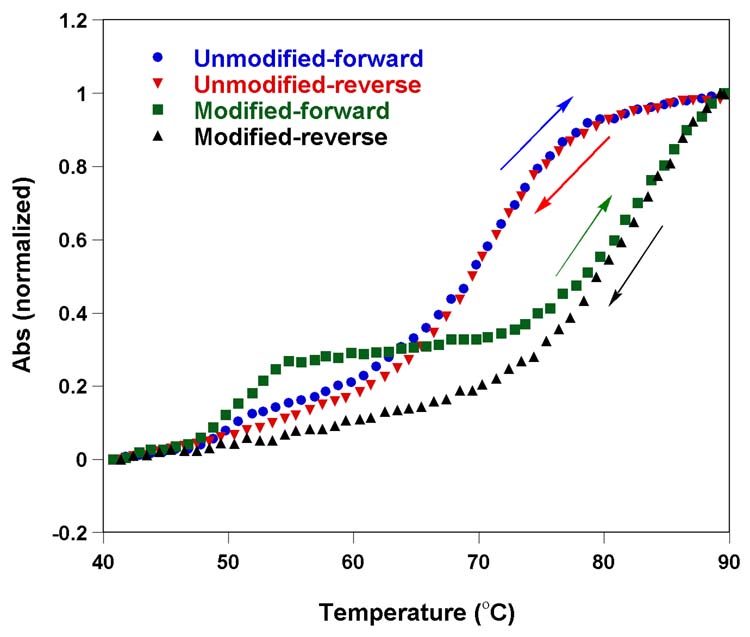

Figure 5.

Thermal melting of unmodified and furan-modified F-TAR1 RNA constructs in 20 mM cacodylate buffer (pH 6.9, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA). Concentration of the duplex was 1 μM. Tm corresponding to hairpin-loop structure of unmodified and furan-modified TAR is 71°C and 82°C, respectively

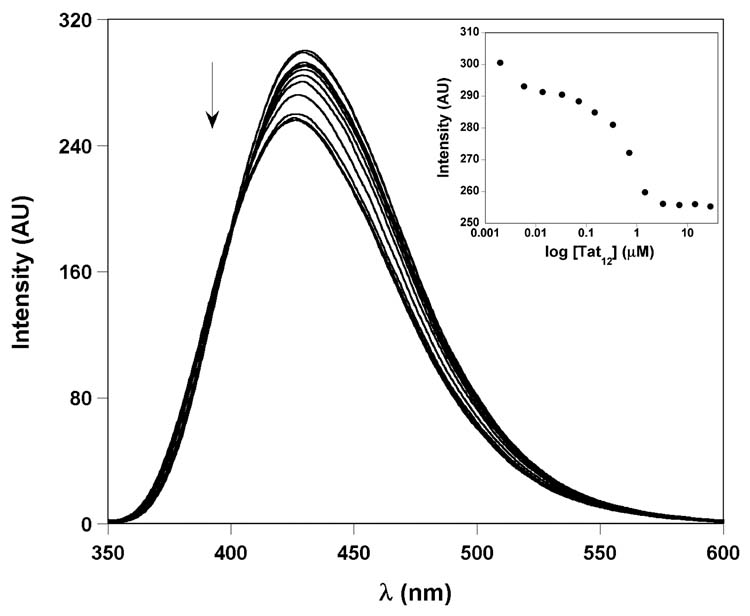

The per-labeled F-TAR1 construct was refolded into the TAR hairpin in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) and was titrated with a short 12 amino acid arginine-rich peptide Tat12 (residues 47–58), containing asparagine at position 54 (Figure 3).39 Changes in emission as a function of Tat12 peptide concentration were monitored at 429 nm. Relatively small changes in fluorescence intensity were observed upon increasing concentrations of the Tat peptide (Figure 6). Although the F-TAR1 construct displayed a saturable binding isotherm with marginal decrease in fluorescence intensity upon Tat binding (less than 15%), a reproducible binding constant could not be derived as small changes in emission intensity led to inconsistent Kd values. Relatively weak fluorescent signal response upon Tat binding can be attributed to the presence of multiple chromophores: either the change in signal is relatively small with respect to the relatively intense total emission (limited dynamic range), or canceling effects among the multiple chromophores result in a relatively minor overall change.

Figure 6.

Representative emission spectra for the titration of F-TAR1 duplex with Tat12 peptide. Fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing concentrations of peptide. Inset: Fluorescence intensity is plotted against log of peptide concentration.

While site-specific modification can, in principle, solve both difficulties mentioned above, this approach presents its own challenges. In particular, the design of the RNA constructs, allowing for the enzymatic incorporation of a single modified residue, becomes more difficult. To circumvent complete modification of all uridine residues during transcription, a duplex RNA construct, F-TAR2, was designed. This bulge-containing heteroduplex, composed of a fluorescent strand T1 and an unmodified complement T2, would essentially represent a stem-loop region as in wild type TAR (Figure 3). This assembly also facilitates selective modification of U23 and U25 in the bulge using the in vitro transcription protocol. It is important to note that similar duplex TAR constructs have previously been employed in scrutinizing the Tat-TAR interaction.14,40

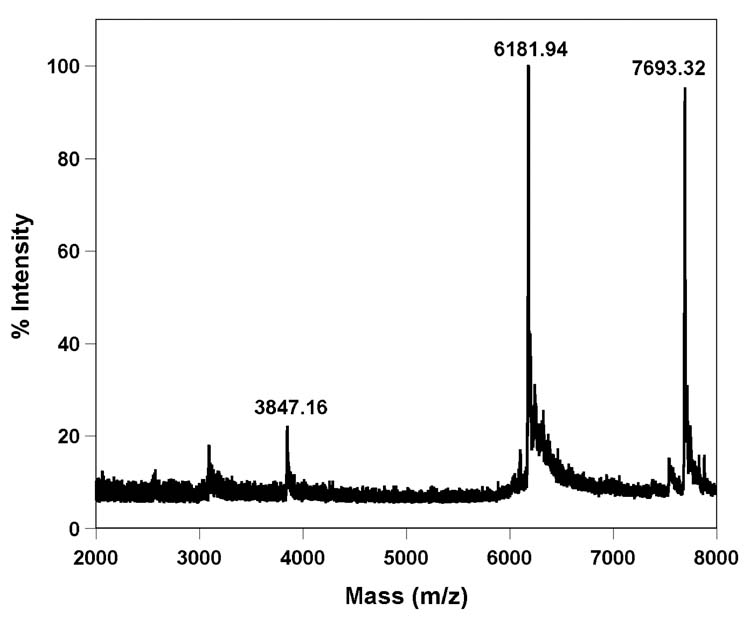

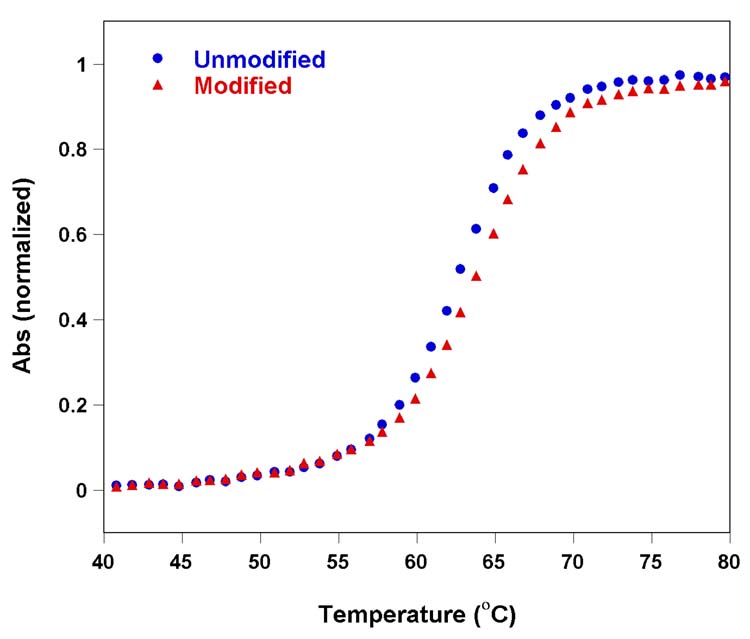

In vitro transcription of the appropriate DNA template in the presence of modified UTP 2 afforded the desired 18-mer RNA product (T1) modified at U23 and U25 (see Experimental Section). Integrity of the 18-mer T1 sequence was confirmed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure 7). The RNA segment T1 and custom made 15-mer RNA strand T2 were then annealed in a 1:1 ratio in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) to form the F-TAR2 duplex. Thermal denaturation studies with the furan modified TAR duplex indicated that the modification had no detrimental effect on duplex stability (Figure 8). In fact, slight stabilization of the modified construct with respect to the unmodified parent RNA is seen. This is consistent with the observations discussed above, illustrating the slight stabilization imparted by the furan modification.

Figure 7.

MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of furan-labeled TAR RNA T1 calibrated relative to the +1 and +2 ions of the internal 25-mer DNA standard (m/z: 7693.32 and 3847.16). Calculated mass [M] = 6178.76; observed mass = 6181.94.

Figure 8.

Thermal melting of un modified (blue) and furan-modified F-TAR2 (red) duplex RNA constructs in 20 mM cacodylate buffer (pH 6.9, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA). Concentration of the duplex was 1 μM. Tm of unmodified duplex and furan-modified duplex are 62.8°C and 63.8°C, respectively.

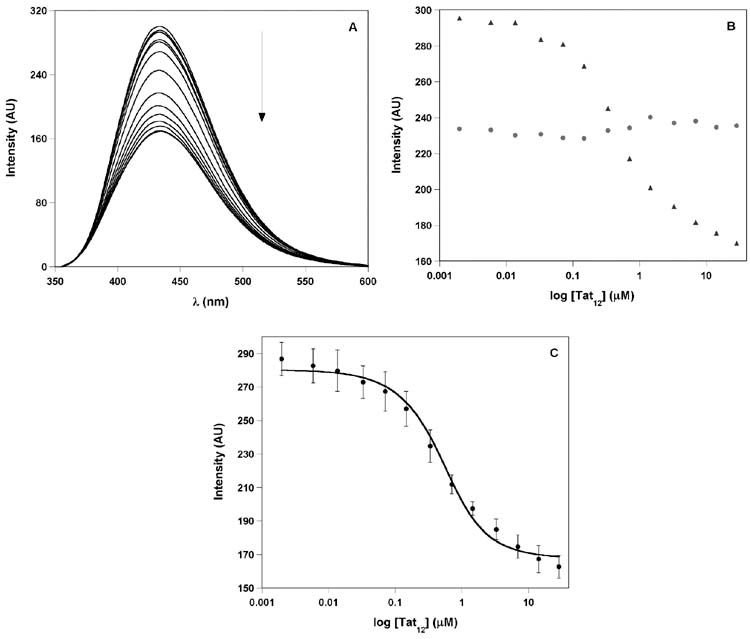

Duplex F-TAR2 (0.50 μM) was excited at 322 nm and changes in emission as a function of Tat12 concentration were monitored at 433 nm (Figure 9A). Addition of Tat12 resulted in quenching of emission, reaching approximately 50% at saturation (Figures 9), displaying a saturable binding isotherm and yielding a Kd of 0.31±0.07 μM (Figure 9C). Importantly, the furan-modified single-strand RNA T1, annealed under identical conditions shows negligible changes in fluorescence with increasing concentration of Tat12 (Figure 9B). This control titration confirms that the fluorescence change observed for F-TAR2 is due to the specific binding of Tat peptide to the TAR duplex and not due to nonspecific interactions.

Figure 9.

Titration of furan-labeled F-TAR2 duplex construct with the Tat12 peptide performed in Tris buffer containing 0.50 μM RNA (see Experimental Section for details). (A) Representative emission spectra for the titration of F-TAR2 duplex with Tat12 peptide. Fluorescence intensity decreased with increasing concentrations of peptide. (B) Fluorescence intensity is plotted against log of peptide concentration. ssRNA, T1 (red) and F-TAR2 duplex (blue). Note the lower emission intensity of the single stranded T1 oligonucleotide. (C) Curve fitting for the titration of duplex F-TAR2 with Tat12 peptide (see Experimental Section for additional details).

The observations associated with the Tat–TAR titration described above need to be addressed. In particular, attention has to be given to the following: (a) the observed quenching of emission upon Tat binding, and (b) the observed dissociation constant.

Unbound TAR adopts an open and accessible major grove conformation in which U23 and C24 are stacked within the helix, while U25 is looped out.33–36 In the bound state the stacked bulge is flipped out of the helix and U23 presumably forms a base triple with A27-U38 assisted by an arginine residue, subsequently leading to a more compact structure that is folded around the basic side chains of the Tat protein.33–36 In the absence of high-resolution structural data for the doubly modified TAR, rationalizing the observed changes in emission is difficult, particularly since the observed signal represents the sum of changes in two presumably independent chromophores. We speculate that in the free F-TAR2 duplex, the furan-modified U23 partially stacks within the helix. Together with the flipped out furan-modified U25, relatively high emission intensity is observed. Upon Tat peptide binding to F-TAR2, the modified U23 and U25 residues are encompassed within a more hydrophobic binding pocket leading to fluorescence quenching. Another plausible explanation for the observed fluorescence quenching induced upon tat binding, could be that the two modified uridines may be close enough to stack in the bound state. The lower fluorescence emission of the single stranded T1, where the two modified residue can stack (Figure 9B), is supportive of such a model.

The Tat12–F-TAR2 titration yields a dissociation constant that is 10–20 fold higher than those reported for longer peptides or the Tat protein binding to TAR.24,26,31 The lower affinity can therefore be attributed to two factors: (a) the length of the peptide utilized, and (b) the incorporation of two nucleotide modification in the RNA sequence. It is well established that longer peptides, 24–38 amino acids in length, exhibit significantly higher affinity and specificity as compared to shorter peptides containing 9–14 amino acids.32 In addition, since the U-rich bulge forms the binding pocket for the Tat protein/peptide, it is not unreasonable to assume that modifications in nucleotides U23 and U25 can potentially lower the binding affinity of the peptide.37 Diminished affinity was also observed for the benzo[g]quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-dione modified TAR.26 Hence, the lower affinity observed for the Tat12-F-TAR2 complex when compared to native Tat–TAR can be attributed to the combination of these two factors. Note, however, that these perturbations do not necessarily diminish the potential utility of such multiple mo difications for the exploration of this and related RNA peptide complexes.

3. Summary

We demonstrated that HIV TAR, an RNA target of potential therapeutic utility, can be effectively labeled using in vitro transcription reactions and examined using fluorescent spectroscopy. Replacing all native uridine residues with the corresponding furan modified fluorescent analogue generates a highly emissive TAR RNA construct that responds to the addition of the Tat peptide with a very small change in total emission. In contrast, when only two strategic U residues are labeled, a reasonable fluorescence response is observed upon Tat titration.

The observations reported here provide insight into the scope and potential limitations associated with the application of fluorescent nucleoside analogues for study of RNA–ligand recognition. Multiple constructs with different labeling patterns should be examined and, if possible, one should consider employing different emissive nucleobases. Predicting the photophysical behavior of site-specifically labeled RNA, based on its sequence and or three dimensional structure, appears, at this stage, to be rather difficult, if not impossible. In particular, different interactions with neighboring bases (acting as potential quenchers) in the free and complexed state can lead to a relatively weak photophysical response, even if binding affinity itself remains minimally affected. Due to these challenges and the increasing demand for “smart” fluorescent probes for biophysical and biotechnological applications, new fluorescent nucleosides with well-characterized structural and photophysical properties are needed. The observations presented in this contribution illustrate how a simple modification of a natural nucleobase can lead to a useful fluorescent isosteric pyrimidine analogue that can be implemented into RNA targets of potential therapeutic utility.

4. Experimental

4.1. Materials

Unless otherwise specified, materials obtained from commercial suppliers were used without further purification. DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. Oligonucleotides were purified by gel electrophoresis and desalted on Sep-Pak (Waters Corporation). NTPs, T7 RNA polymerase, ribonuclease inhibitor (RiboLock) were obtained from Fermentas Life Science. Custom RNA oligonucleotides procured from Dharmacon RNA Technologies were deprotected according to supplier’s procedure, gel-purified and desalted before use. Tat12 was obtained from AnaSpec, Inc. Chemicals for preparing buffer solutions were purchased from Fisher Biotech (enzyme grade). Autoclaved water was used in all biochemical reactions and fluorescence titrations.

4.2. Instrumentation

All MALDI-TOF spectra were collected on a PE Biosystems Voyager-DE STR MALDI-TOF spectrometer in positive-ion, delayed-extraction mode. UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett Packard 8452A diode array spectrometer. Steady State fluorescence experiments were carried out in a micro fluorescence cell with a path length of 1.0 cm (Hellma GmH & Co KG, Mullenheim, Germany) on a Perkin Elmer LS 50B luminescence spectrometer.

4.3. Synthesis of TAR ssRNA T1 and F-TAR1

An 18-mer T7 promoter sequence was annealed to DNA templates 5′ GCTGCTCAGATCTGCCGCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA3′ and 5′ GGCAGAGAGCTCCCAGGCTCAGATCTGCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA 3′, respectively, in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8) by heating a 1:1 mixture (5 μM) at 90°C for 2 min and cooling the solution slowly to room temperature. Transcription reactions were performed in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.9) containing 300 nM annealed template, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM spermidine, 0.4 U/μL RNase inhibitor (RiboLock), 3 mM GTP, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM CTP, 2 mM modified UTP 2, and T7 RNA polymerase (300–700 units) in a total volume of 250 μL. After incubating for 15 h at 37°C, the precipitated magnesium pyrophosphate was removed by centrifugation. The reaction volume was reduced to half by Speed Vac and 25 μL of loading buffer (7 M urea in 10 mM Tris -HCl, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8 and 0.05% bromophenol blue) was added. The mixture was heated at 75°C for 3 min, and loaded onto a preparative 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was UV shadowed; appropriate bands were excised, extracted with 0.5 M ammonium acetate and desalted on a Sep-Pak. Integrity of the full length furan-modified RNA transcripts was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

4.4. MALDI-TOF MS

Molecular weight of control and modified oligonucleotides were determined via MALDI-TOF MS. 1 μL of a ~100 μM stock solution of each oligonucleotide was combined with 1 μL of 100 mM ammonium citrate buffer (PE Biosystems), 1 μL of a 75 μM DNA standard (25-mer) and 4 μL of saturated 3-hydroxypiccolinic acid. The samples were desalted with an ion exchange resin (PE Biosystems) and spotted onto a gold-coated plate where they were air dried. The resulting spectra were calibrated relative to the +1 and +2 ions of the internal DNA standard, thus the observed oligonucleotides should have a resolution of ±2 mass units. RNA T1, Calculated mass [M] = 6178.76; observed mass = 6181.94. F-TAR1, Calculated mass [M] = 9922.21; observed mass = 9922.85.

4.5. Fluorescence Binding Assay

Furan-modified RNA constructs were excited at 322 nm with an excitation slit width of 15 nm and emission slit width of 20 nm, and changes in fluorescence were monitored at the emission maximum, 433 nm. F-TAR1 construct was more emissive than F-TAR2 and hence shorter emission slit width (15 nm) was used. For binding experiments, TAR duplex was annealed in Tris binding buffer (50 mM Tris -HCl, 100 NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.001% Nonidet P40), by heating 1:1 mixture at 90°C for 2 min and cooling the solution slowly to room temperature, followed by incubating the mixture in ice. All fluorescence titration were performed in triplicate. Standard deviation was less than ±4%.

4.6. Binding of Tat12 to F-TAR duplex model

In a typical binding experiment, the fluorescence spectrum of a 122.5 μL solution of Tris buffer in the absence of RNA was recorded. This spectral blank, for which only Raman scatter was observed, was subtracted from all subsequent spectra within each titration. Following determination of the buffer blank, 2.5 μL of F-TAR2 duplex (25 μM) formed from ssRNA T1 and T2 was added (final duplex concentration, 0.50 μM). The solution was mixed well and the spectrum was recorded again. Subsequent aliquots (1 μL) of increasing concentrations of Tat12 were added, and the fluorescence spectrum was recorded after each aliquot until fluorescence saturation was achieved. The change in volume over the entire titration was =10%. Equation 1 was used for the determination of the dissociation constant for the interaction of TAR duplex and Tat peptide, where F and F0 are the fluorescence intensity of the duplex RNA in the presence and absence of Tat12 peptide, respectively. ?F is the difference between the fluorescence intensity of RNA at saturation and in the absence of peptide. [RNA]0 and [P]0 are the initial concentrations of the duplex RNA and Tat12 peptide.26,41

| (1) |

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mr. Nicholas Greco for his help with mass spectral measurements. We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (grants AI 47673 and GM 069773) for support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Frankel AD, Young JAT. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner BG, Summers MF. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1–32. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharp PA, Marciniak RA. Cell. 1989;59:229–230. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen CA, Pavlakis GN. AIDS. 1990;4:499–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen BR. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:375–394. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.375-394.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MR. In: AIDS Research Reviews III. Koff WC, Wong-Staal F, Kennedy RC, editors. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 1993. pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karn J. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:235–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rana TM, Jeang KT. Archiv Biochem Biophys. 1999;365:175–185. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arzumanov A, Walsh AP, Liu XH, Rajwnashi VK, Wengel J, Gait MJ. Nucleoside Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:471–480. doi: 10.1081/NCN-100002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamilarasu N, Huq I, Rana TM. Bioorg Med Chem Letts. 2000;10:971–974. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, Huber PW, Cui M, Czarnik AW, Mei HY. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5549–5557. doi: 10.1021/bi972808a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litovchick A, Lapidot A, Eisenstein M, Kalinkovich A, Borkow G. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15612–15623. doi: 10.1021/bi0108655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang S, Tamilarasu N, Ryan K, Huq I, Richter S, Still WC, Rana TM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12997–13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamy F, Felder ER, Heizmann G, Lazdins J, Aboul-Ela F, Varani G, Karn J, Klimkait T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3548–3553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karn J, Churcher MJ, Rittner K, Kelley A, Butler PJG, Mann DA, Gait MJ. HIV. In: Karn J, editor. A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1995. p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs A, Ludwig V, Boden O, Göbel MW. Chem Bio Chem. 2003;4:972–978. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wojczewski C, Stolze K, Engels JW. Synlett. 1999:1667–1678. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins ME. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2001;34:257–281. doi: 10.1385/CBB:34:2:257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy CJ. Adv Photochem. 2001;26:145–217. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rist MJ, Marino JP. Curr Org Chem. 2002;6:775–793. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto A, Saito Y, Saito IJ. Photochem Photobiol C: Photochem Rev. 2005;6:108–122. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranasinghe RT, Brown T. Chem Commun. 2005:5487–5502. doi: 10.1039/b509522k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverman AP, Kool ET. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3775–3789. doi: 10.1021/cr050057+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradrick TM, Marino JP. RNA. 2004;10:1459–1468. doi: 10.1261/rna.7620304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blount K, Tor Y. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:5490–5500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arzumanov A, Godde F, Moreau S, Toulmé JJ, Weeds A, Gait MJ. Helv Chim Acta. 2000;83:1424–1436. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greco NJ, Tor Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10784–10785. doi: 10.1021/ja052000a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivatsan SG, Tor Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2007 doi: 10.1021/ja066455r. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calnan BJ, Tidor B, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel AD. Science. 1991;252:1167–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weeks KM, Ampe C, Schultz SC, Steitz TA, Crothers DM. Science. 1990;249:1281–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.2205002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long KS, Crothers DM. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8885–8895. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weeks KM, Crothers DM. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10281–10287. doi: 10.1021/bi00157a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long KS, Crothers DM. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10059–10069. doi: 10.1021/bi990590h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aboul-ela F, Karn J, Varani G. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:313–332. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puglisi JD, Tan R, Calnan BJ, Frankel AD, Williamson JR. Science. 1992;257:76–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1621097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weeks KM, Crothers DM. Cell. 1991;66:577–588. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churcher MJ, Lamont C, Hamy F, Dingwall C, Green SM, Lowe AD, Butler PJG, Gait MJ, Karn J. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:90–110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delling U, Reid LS, Barnett RW, Ma MYX, Climie S, Sumner-Smit M, Sonenberg N. J Virol. 1992;66:3018–3025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3018-3025.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Previous mutation studies in the basic Tat domain reveal that the glutamine residue at position 54 is not essential for binding or activity: Calnan BJ, Biancalana S, Hudson D, Frankel AD. Genes Dev. 1991;5:201–210. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.201.

- 40.Hamy F, Asseline U, Grasby J, Iwai S, Pritchard C, Slim G, Butler JG, Karn J, Gait MJ. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:111–123. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho J, Hamasaki K, Rando RR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4985–4992. doi: 10.1021/bi972757h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]