Abstract

Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a proangiogenic transcription factor stabilized and activated under hypoxia. It regulates the expression of numerous target genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other cytoprotective proteins. In this study, we hypothesized that bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) secrete growth factors which protect cardiomyocytes via HIF-1α pathway.

Methods

BMSCs were obtained from transgenic mice overexpressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). The study was carried out in vitro using co-culture of BMSCs with cardiomyocytes. LDH release, MTT uptake, DNA fragmentation and annexin-V positive cells were used as cell injury markers. The level of HIF-1α protein as well as its activated form and VEGF were measured by ELISA. The expression of HIF-1α and VEGF in BMSCs were analyzed by quantitative PCR and cellular localization was determined by immunohistochemistry.

Results

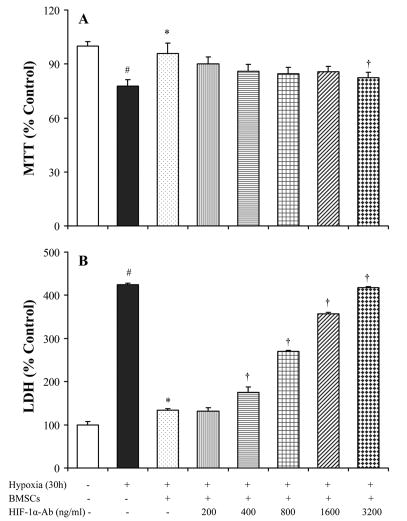

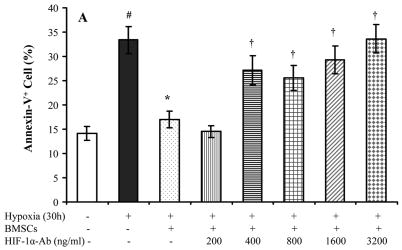

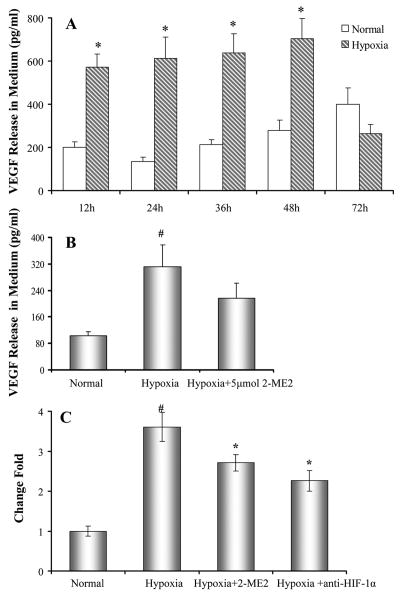

LDH release was increased and MTT uptake was decreased after exposure of cardiomyocytes to hypoxia for 24 hours, which were prevented by co-culturing cardiomyocytes with BMSCs. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by hypoxia and H2O2 was also reduced by co-culture with BMSCs. VEGF release from BMSCs was significantly increased in parallel with high level of HIF-1α in BMSCs following anoxia or hypoxia in time-dependent manner. Although no significant up-regulation could be seen in HIF-1α mRNA, HIF-1α protein and its activated form were markedly increased and translocated to the nucleus or peri-nuclear area. The increase and translocation of HIF-1α in BMSCs were completely blocked by 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME2; 5μmol), a HIF-1α inhibitor. Moreover, the protection of cardiomyocytes by BMSC and VEGF secretion were abolished by neutralizing HIF-1α antibodies in a concentration dependent manner (200~ 3200ng/ml).

Conclusion

Bone marrow stem cells protect cardiomyocytes by up-regulation of VEGF via activating HIF-1α.

Keywords: bone marrow stem cells, HIF-1α, VEGF, cardiomyocytes, hypoxia, HIF-1α neutralizing antibody

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial infarction is a leading cause of heart failure. Cardiac stem cells [1] and human embryonic stem cells [2] and bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) [3–5] have been shown to participate in myocardial repair process and repopulate the infarcted myocardium. Under normal conditions, BMSCs are rarely seen in tissue and organs. However, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) enhances their mobilization into blood circulation and their lodging in the damaged tissue to repair ischemic myocardium [6–9]. Moreover, BMSCs can be directly transplanted into infarcted area by intra-coronary infusion or catheter based intra-myocardial injection or direct intra-myocardial injection [10]. The mobilized or transplanted BMSCs significantly improve left ventricular function [3–5] which might be due to better regional perfusion and systolic function following acute coronary artery occlusion [10, 11] and transdifferentiation into functional active cardiomyocytes [3, 4, 12]. However, some studies reported that transdifferentiated cardiomyocytes from BMSCs were not detected in the repaired tissue [13].

It is well known that the loss of cardiac myocytes is the major problem in heart failure; thus, it is important to protect native cardiac myocytes and preserve myocardial tissues against cell death besides regeneration of injured heart. A growing body of evidence has shown that VEGF, a endothelial cell-specific angiogenic factor, induces expression of Bcl-2 which eventually functions to enhance cell survival in the anoxic and oxygen-deficient environment [14] and activates the myocardial PI-3K pathway to decrease myocardial infarct size [15]. Low oxygen tension is common phenomenon in ischemic cardiomyopathic hearts. Our previous study has shown that BMSCs secret VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1), which were increased from 30% to 150% after BMSCs were exposed to anoxia for 4 hours [4]. It is unclear which pathway is activated in BMSCs under lower oxygen tension to induce up-regulation of these cyto-protective proteins. Some studies reported that hypoxia triggers hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) signaling pathway. HIF-1 consists of a constitutively expressed subunit HIF-1β and an oxygen-regulated subunit HIF-1α [16, 17]. HIF-1α protein is ubiquitously expressed, whereas its homologues HIF- 2α and HIF-3α have more restricted expression patterns. Under lower oxygen tension, hydroxylation is inhibited because of substrate (O2) deprivation, and HIF-1α accumulates, dimerizes with HIF-01β, and mediates profound changes in hypoxia-inducible genes (HIGs) expression [18, 19]. To our knowledge, there are no reports on the role of HIF-1α on the ischemic heart repair by BMSCs. We hypothesize that BMSCs directly protect cardiomyocytes by up-regulation of cardio-protective protein, VEGF via activating HIF-1α under lower oxygen tension environment.

METHOD

Cell culture

BMSCs were isolated according to the method described by us previously [20]. In brief, femurs and tibias from green fluorescent protein (GFP)–transgenic mice developed by Hadjantonakis et al [21] were removed. Muscle and extraossial tissue were trimmed. Bone marrow cells were flushed and cultured with Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 20% FBS and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in humid air with 5% CO2. After being seeded for 2 days, BMSCs adhered to the bottom of culture plates, and hematopoietic cells remained suspended in the medium. The non-adherent cells were removed by a medium change at 48 hours and every 4 days thereafter. Myocytes were isolated and cultured from ventricles of 2-day-old neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, Ind) using the neonatal cardiomyocyte isolation kit (Worthington biochemical Co. NJ) as previously described [20].

In vitro ischemic model

To mimic the ischemic injury in vitro, cells were incubated under hypoxia or anoxia for various periods after the medium was replaced with a new serum free medium for 16 hours. For anoxia, cells were exposed to anaerobic glucose-free medium and placed into the anoxic chamber (Forma 1025 anaerobic system). For hypoxia, cells were exposed to low glucose (1g/L) DMEM and placed in hypoxic incubator (Sanyo, O2/CO2 incubator-MCO-18M) and oxygen was adjusted to 1.0% and CO2 to 5%. Normal culture (serum free regular medium under 21% oxygen and 5% CO2) served as a control. LDH release and MTT intake were used as cell injury parameters. Apoptosis was determined by annexin-V (MBL International) binding test and DNA fragmentation (Biovision) following manufacture’s instructions. In some experiments, cells were exposed to 200 μmol H2O2 for 2 hours to induce cell apoptosis. To confirm the role of HIF-1α in the protection by BMSCs on cardiomyocytes, cells were pretreated with different concentrations of HIF-1α neutralizing antibody or 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME2), a HIF-1α inhibitor for 1 or 16 hours, respectively. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and each experiment was repeated three times unless otherwise mentioned.

Measurement of VEGF and HIF-1α protein by ELISA

VEGF release from BMSCs into culture medium was directly measured by ELISA kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems). As a control, basal media were also analyzed. The absorbance was measured at 450nm and 570nm.

Total HIF-1α protein was extracted from whole cells. The cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer (pH 7.4) including (mM) Tris 50; EDTA 3; MgCl2 1; β-glycerophosphate 20; NaF 25; NaCl 300; 10% (w/v) glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Whole cell extract was obtained by centrifuging the lysates at 16,000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes followed by sonication. Total HIF-1α was detected by ELISA mouse total HIF-1α kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of HIF-1α was calibrated with HIF-1α standard curve. Activated HIF-1α was measured from nuclear extract which was obtained by solubilizing nuclear pellet in freshly prepared cold lysis buffer (mM) containing: HEPES (pH 7.9) 20; MgCl2 1.5; NaCl 420; DTT 0.5, Na3VO4 2; NaF 5; 25% glycerol, 25μg/mL Chymostatin and protease inhibitor cocktail. After centrifugation the lysates at 16,000 × g at 4° C for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected. The values were corrected for total protein. To measure the active HIF-1α, 50μg/well nuclear extracts were incubated with biotinylated double stranded (ds) oligonucleotide containing a consensus HIF-1α binding site from Duo-set ELISA mouse active HIF-1α kit (R&D Systems). The activity of HIF-1α was expressed by OD (450nm–570nm).

RNA preparation and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated and purified from cell pellet using the RNeasy mini kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Using SuperScript™ III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen), 1μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to synthesize first-strand cDNA (total 20 μl). Two μl of the reverse transcription reaction was mixed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and amplified by iQ5 real-time system (Bio-Rad). The product was quantified using a standard curve that calculated each cycle number at which the amplification of the product was in the linear phase. To ensure the fidelity of the mRNA extraction and reverse transcription, this value was normalized to the value of the internal standard glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) for each analysis. Primers for amplification of VEGF, HIF-1α and GAPDH are listed below.

HIF-1α: Sense primer 5′-CTGCTGTCTTACTGGTCCTT 3′; Anti-sense primer 5′-GTC GCT TCT CCA ATT CTT AC-3′. VEGF: Sense 5′-ATG AAC TTT CTG CTC TCT GG-3′; Antisense: 5′-TCA TCT CTC CTA TGT GCT GGC-3′. GAPDH: Sense 5 ′-TGC AGT GGC AAA GTG GAG-3′; Anti-sense 5 –ACA TAC TCA GCA CCG GCC TC-3′ The expression of each target mRNA relative to GAPDH under experimental and control conditions was calculated based on the threshold cycle (CT) as r = 2−Δ (ΔCT), where ΔCT = CT target − CT GAPDH and Δ(ΔCT) = ΔCT experimental − ΔCT control.

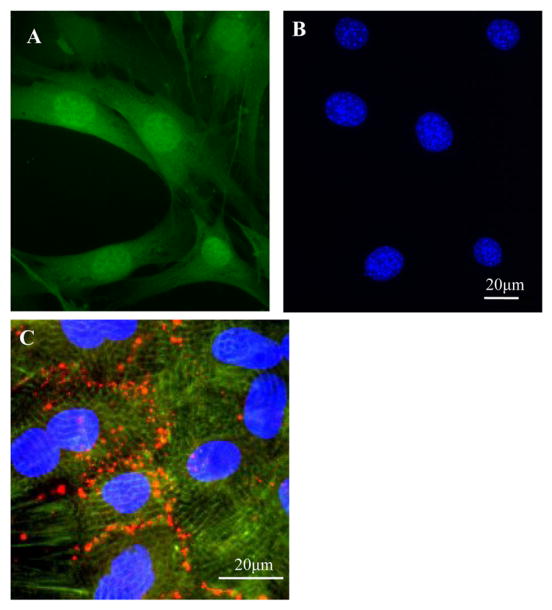

Immunofluorescence and histological analysis

For HIF-1α staining, cells cultured on glass coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HIF-1α (sigma). After washing thoroughly, the secondary antibodies of goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa 546 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were applied. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). Myocyte staining is similar to our previous report [22]. Fluorescent images were processed using Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with an Olympus U-TV0.5XC digital camera (Olympus, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with an unpaired Student t test for comparison between 2 groups. A probability value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

1. BMSCs protected cardiomyocytes against ischemic injury

Previous studies indicated that the improvement of cardiac function by transplanted stem cells might partially be due to the direct protection of native cardiomyocytes by stem cells [23, 24]. To assess cardiomyocyte protection, BMSCs were co-cultured with myocytes at a ratio of 1: 20. BMSCs had the tendency to grow in clusters (Figure 1A). The nucleus of each BMSC had more than one nucleolus (Figure 1B). Cardiomyocytes began to beat spontaneously after being cultured for 24 hours. Immunostaining showed that myocytes were positive for α-actinin and myofibers were seen with clear Z-lines in sarcomeres. Myocytes had physical contacts with neighboring myocytes via connexin 43 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

BMSCs were obtained from transgenic mice expressing GFP and cardiomyocytes from neonatal rat ventricles. A, Primary cultured GFP-positive BMSCs. B, Same as “A”, but the nuclei of BMSCs were stained with DAPI. C. Cultured myocytes were positive for α-actinin (green). Connexin 43 (red) was observed between myocytes. The nuclei were stained with DAPI.

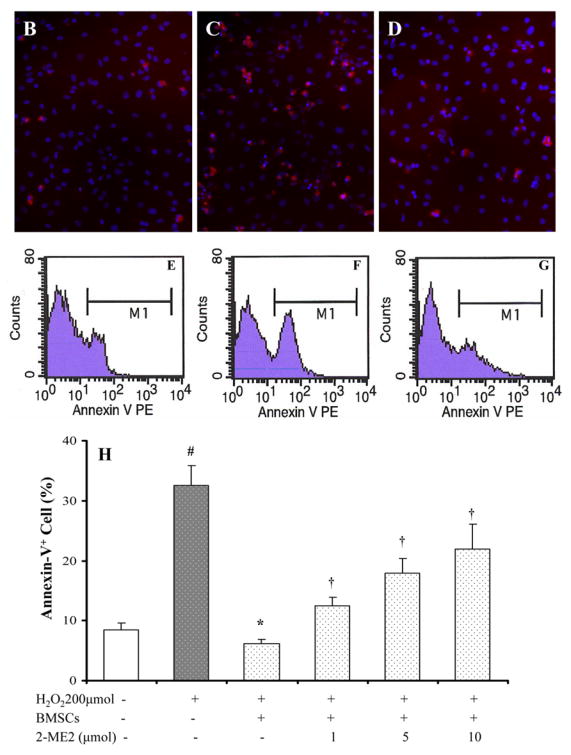

To determine that BMSCs provided protection to myocytes under lower oxygen environment, a series of parameters were used to determine cell injury. After exposure to hypoxia for 24 hours, MTT uptake was significantly decreased and LDH release from myocytes was significantly increased. A significant reduction in LDH release and an increase of MTT uptake were observed in myocytes which were co-cultured with BMSCs (Figure 2). DNA fragmentation was seen in myocytes after exposure to hypoxia for 48 hours (Figure 3A), which could be prevented by co-culturing with BMSC. However, co-culture with BMSCs was ineffective to prevent DNA fragmentation if hypoxia was prolonged to 72 hours (Figure 3B). To quantify myocyte apoptosis, cells were labeled with annexin V-PE following hypoxia. The cells were examined under fluorescence microscope and counted by FACS. Co-culture with BMSCs significantly reduced annexin V positive cardiomyocytes and were ineffective in the presence of HIF-1α antibody (Figure 4). To further demonstrate the protection of cardiomyocytes by BMSCs against oxidative stress, H2O2 was used to mimic oxidative stress. The number of apoptotic cells was significantly increased after myocytes exposure to H2O2 (200 μmol) for 2 hours (32.5 ± 3.3 % vs 8.4 ± 1.1 % in normal control, p < 0.05). The Annexin V positive cells were significantly reduced in co-culture cells as compared with treatment with H2O2 alone (6.1 ± 0.7 % vs 32.5 ± 3.3 %, p < 0.05). However, the protection by BMSC was abolished by pretreating cells with HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies (200 ~ 3200 ng/ml) or 2-ME2 (1~10 μmol) in a concentration–dependent manner (Figure 4A, 4H).

Figure 2.

LDH release and MTT uptake by cultured cardiomyocytes under different treatments. # p < 0.05 vs normal control; * p < 0.01 vs myocytes alone; † p < 0.05 vs myocytes co-cultured with BMSC.

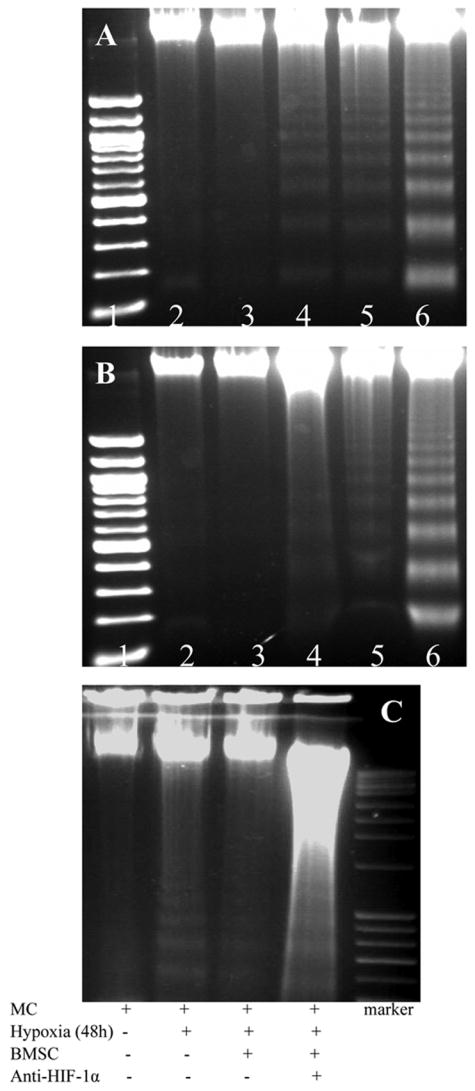

Figure 3.

Effect of BMSCs on DNA fragmentation under hypoxic conditions. Panel A: myocytes alone, Panel B: Myocytes co-cultured with BMSCs (Lane 1: marker; Lane 2: normal; Lane 3: Hypoxia 24h; Lane 4: Hypoxia 48h; Lane 5: Hypoxia 72h; Lane 6: positive control). Panel C. Myocytes co-cultured with BMSC before and after anti-HIF-1α antibody treatment.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis assay after cells were exposed to hypoxia for 30 hours and H2O2 (200μmol) for 2 hours. A. Hypoxic treatment. B~G: H2O2 treatment. Panel B–D: Annexin V positive cells are shown in red color; Panel E–G: flowcytometry assay. Panels B and E: normal cultured myocytes; Panels C and F: H2O2 treated myocytes; Panels D and G: H2O2 treated cardiomyocytes co-cultured with BMSCs; Panel H. Percentage of annexin V positive cells after H2O2 treatments. # p < 0.05 vs normal cultured myocytes; * P < 0.05 vs hypoxia- or H2O2-treated myocytes alone. † p < 0.05 vs myocytes co-cultured with BMSCs.

2. Hypoxia up-regulated HIF-1α

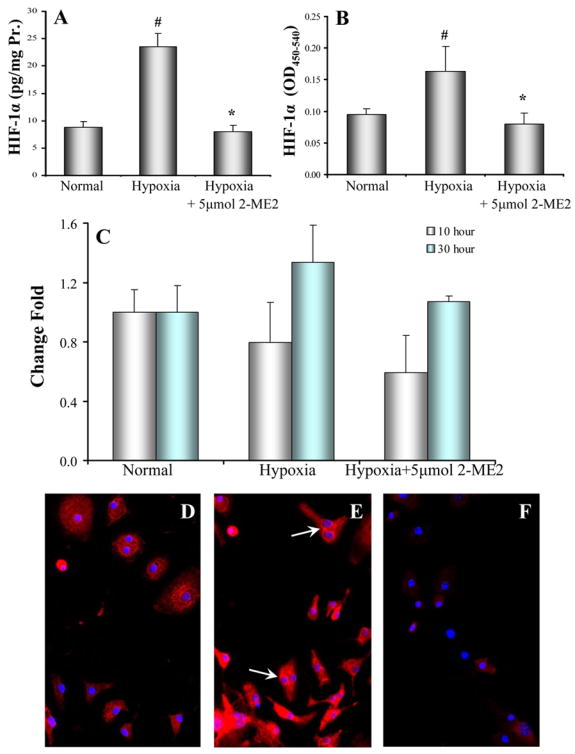

It is generally known that HIF-1α pathway is activated when cells are exposed to lower oxygen tension. We asked whether HIF-1α pathway is also activated in BMSCs during hypoxia. HIF-1α protein was significantly increased in BMSCs which were exposed to hypoxia as compared to BMSC cultured under normal conditions (Figure 5A). Hypoxia not only increased HIF-1α in whole cell lysate, but also activated HIF-1α in nuclei (Figure 5B). However, hypoxia did not increase HIF-1α RNA in cultured bone marrow stem cells (Figure 5C). In normal conditions, HIF-1α was mainly localized in the cytosol (Figure 5D). Hypoxia induced the translocation of HIF-1α into the nuclei or to peri-nucleus areas (Figure 5E, arrows). The up-regulation and translocation of HIF-1α protein were completely abolished by pre-treating cells with 2-ME2 (5μmol) (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Activity and distribution of HIF-1α in BMSCs. Panel A: Total HIF-1α (n = 10) and Panel B: Activity of HIF-1α (n = 8) in the BMSCs under hypoxia for 30 hours. It was inhibited by 2-ME2. # p < 0.05 vs normal culture and * p < 0.05 vs hypoxia alone. Panel C: Quantitative PCR for HIF-1α mRNA (n = 4). There was no significantly difference among various treatments. Panel D. HIF-1α was scattered in cytosol of normal BMSCs; Panel E: HIF-1 was highly concentrated in peri-nucleus and in nuclei (arrows) after BMSCs were exposed to hypoxia for 30 hours. Panel F. Pretreatment of cells with 2-ME2 (5 μmol) for 16 hours significantly abolished the translocation of HIF-1α. Red: HIF-1α; Blue: DAPI (nuclei).

3. BMSCs secreted VEGF and protected cardiomyocytes

VEGF is one of the downstream genes of HIF-1α. Secretion of VEGF from BMSCs was assayed by ELISA. Figure 6A showed that VEGF release was significantly increased in BMSCs after exposure to hypoxia compared to cells cultured in normal condition and was decreased when cells were exposed to hypoxia for 72 hours. Also the release of VEGF from BMSCs was decreased by pretreatment with 2-ME2 (Figure 6B). To further confirm the relationship of VEGF release with the HIF-1α activity, specific HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies were used. Quantitative PCR data showed that VEGF mRNA was significantly upregulated in BMSCs after exposure to hypoxia for 10 hours. The over-expression of VEGF by hypoxia was abolished by HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies and 2-ME2 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Secretion of VEGF by BMSCs. Panel A. VEGF release from BMSCs. *, p < 0.05 vs normal culture, respectively. Panel B: Release of VEGF from BMSCs by exposure to 30 hours hypoxia was partially inhibited by 2-ME2 (5μmol). # p < 0.05 vs normal culture 10 hours. Panel C. The expression of VEGF in BMSCs. Bars represent the fold increase in VEGF concentrations measured in hypoxic cultured BMSCs relative to normoxic conditions. The expression of VEGF was significantly reduced by specific HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies (3200 ng/ml) and HIF-1α inhibitor 2-ME2 (5 μmol). #, p < 0.05 vs normal culture; *, p < 0.05 vs cells exposed to hypoxia.

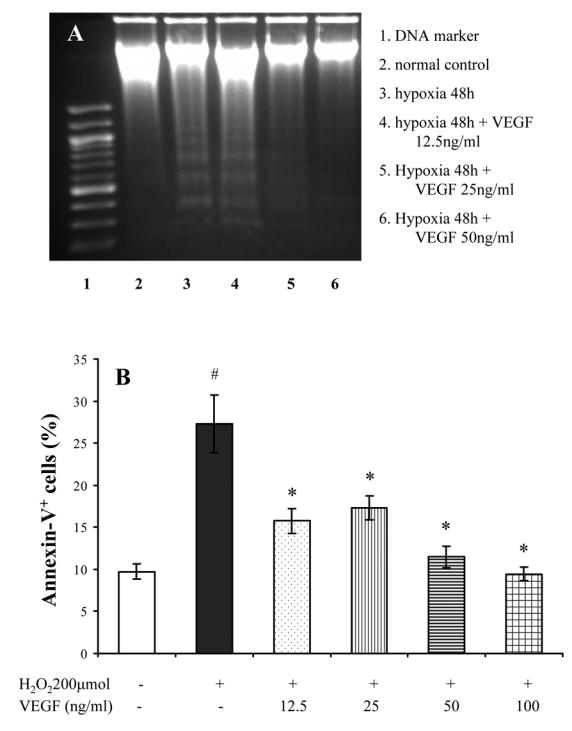

To duplicate the protective effect of VEGF on cardiomyocytes, cardiomyocytes were pretreated with exogenous VEGF (0~50 ng/ml) for 16 hours. Indeed, VEGF (12.5 ~ 100ng/ml) prevented DNA fragmentation of cultured myocytes following 48 hours hypoxia and reduced the number of annexin-V positive cells after exposure to H2O2 (200 μmol) in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of VEGF on cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Panel A: VEGF reduced the DNA fragmentation induced by hypoxia. Panel B: VEGF also prevented apoptosis of myocytes exposed to H2O2 (200 μmol/L) for 2 hours. #, p < 0.05 vs normal culture; *, p < 0.05 vs myocytes exposed to H2O2.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated for first time that bone marrow stem cells protected cardiomyocytes against ischemic injury through secreting VEGF via activating HIF-1α pathway. The cell apoptosis was prevented by VEGF released by BMSC under lower oxygen tension environment via activation of HIF-1α pathway. The secretion of VEGF from BMSCs was positively co-related with HIF-1α activity which was abolished by a HIF-1α inhibitor, 2-ME2 and specific HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies in a concentration-dependent manner.

1. BMSCs protected cultured cardiomyocytes via secretion of VEGF

It is generally agreed that protection of cardiac myocytes is critical in the repair of ischemic heart since the loss of cardiac myocytes is the major cause of heart failure. The repair process includes protection of native cardiomyocytes in early stage and myogenesis of new cardiomyocytes from stem cells at later stage. Therefore, preservation of host myocardial tissues is one of the benefits of stem cell based strategies after MI. The present in vitro study provided direct evidence that BMSCs preserved native myocytes by preventing cell apoptosis induced by oxidative stress.

Various growth factors, including IGF and VEGF have been shown to protect the heart against oxidative stress [25–27]. The release of VEGF from cultured cardiomyocytes was significantly increased when they were exposed to anoxia for 15 hours (375.29 ± 79.1vs 160.54 ± 50.24 pg/ml in normal control, p < 0.05) (our unpublished data). However, the release of VEGF from cardiomyocytes does not appear to be enough to protect cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress. Our previous study has shown that BMSCs secreted a number of growth factors, which were enhanced by exposure to mild anoxia [4]. Here, we further demonstrated a significant increase in VEGF, but not IGF (data not shown) in BMSCs under hypoxic conditions both at protein and mRNA levels. The protection by VEGF was further duplicated by exogenous VEGF given during hypoxia. It suggests that BMSCs protect myocytes via secretion of VEGF. Tang et al have reported that implantation of mesenchymal stem cells significantly elevated VEGF expression which was accompanied by increased vascular density and regional blood flow in the infarct zone [28]. Moreover, it has been reported that implantation of bone marrow stem cells transfected with phVEGF165 can increase the survival of implanted cells, and enhance the cardiac function after acute myocardial infarction [29]. The latter study also showed that VEGF protected cells against apoptosis. VEGF has direct neurotrophic and neuroprotective as well as angiogenic properties. It exerts neuroprotective actions directly through the inhibition of apoptosis and the stimulation of neurogenesis [30]. The mechanism of VEGF in the prevention of apoptosis is not clear yet. VEGF may bind to its receptors and trigger the phosphatidyloinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signal transduction system thus resulting in the inhibition of apoptosis by activating antiapoptotic proteins through the transcription factor NF B and by suppressing proapoptotic signaling by Bad, caspase-9, caspase-3, and other effectors [30].

2. Activation of HIF-1α pathway induced VEGF release

The cellular mechanism by which BMSCs secrete VEGF in response to low oxygen environment is unknown. In this study, no significant changes in HIF-1α mRNA were observed in BMSC after exposure to hypoxia for 10 ~30 hours. However, HIF-1α protein and its active form were significantly increased in lower oxygen tension environment (Figure 5). HIF-1α was further translocated to the nucleus and peri-nuclear areas following hypoxia. HIF-1 is a transcription factor which facilitates the adaptation of cells and tissues to low O2 concentrations [16, 17]. It has been demonstrated that the transcription and synthesis of HIF-1α are constitutive and regulated by its degradation rate [31, 32].

Regulation of HIF-1α function primarily occurs at the posttranslational level. It has been reported that 2-ME2 down regulates HIF-1α at the post-transcriptional level and inhibits HIF-1α-induced transcriptional activation of VEGF expression in human breast and prostate cancer [33]. Our data shows that 2-ME2 blocked the protection by BMSCs in a concentration-dependent manner in parallel with down-regulating the HIF-1α protein levels and activity, but has no significant effect on HIF-1α mRNA expression. Moreover, 2-ME2 partially attenuated the release of VEGF from BMSCs. This suggests that 2-ME2 abrogated the protection by BMSC by partially abolishing VEGF release from BMSC via HIF-1α pathway. Mabjeesh et al. [34] reported that 2-ME2 inhibited HIF-1α protein synthesis and proposed that this effect was a consequence of microtubule disruption by 2-ME2. 2-ME2 also inhibited HIF-1α transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner, as determined by using a hypoxia-responsive reporter construct [35].

Inhibition of VEGF expression and loss of protection by specific HIF-1α neutralizing antibodies support our hypothesis that HIF-1α plays a very important role in secretion of VEGF from bone marrow stem cells under hypoxia. HIF-1α protein is steady [31, 32] under low O2 levels (<5%) and translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β, and forms a dimer with aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator protein (ARNT). The heterodimer HIF-1α-ARNT is a transcriptional activator of genes and results in expression of several hypoxia-inducible genes, including erythropoietin, VEGF, glucose transporters, and glycolytic enzymes, etc [16, 36]. HIF-1α heterodimerizes with HIF-1β and binds to hypoxia response elements, thereby activating the transcription of numerous genes important for adaptation and survival under hypoxia [37, 38]. Kimbro and Simons reviewed [33] that HIF-1α signaling induced VEGF release by activating the protein tyrosine kinase c-Src and/or its downstream mediator phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Src and PI3K activation appears to increase the stability of HIF-1α, thereby, increasing VEGF levels [39]. Several investigators have demonstrated that optimal transcriptional control of the VEGF promoter requires binding of both HIF-1α and STAT3 [40–42].

In summary, VEGF secretion by BMSCs is regulated by the activation of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions where it protects cardiomyocytes against injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37-HL074272, HL087246, HL080686, HL70062 (M. Ashraf), HL083236 (M. Xu), HL081859 (Y. Wang).

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Urbanek K, Torella D, Sheikh F, De Angelis A, Nurzynska D, Silvestri F, et al. Myocardial regeneration by activation of multipotent cardiac stem cells in ischemic heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Jun 14;102(24):8692–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue T, Cho HC, Akar FG, Tsang SY, Jones SP, Marban E, et al. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes: insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005 Jan 4;111(1):11–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Haider H, Ahmad N, Zhang D, Ashraf M. Evidence for ischemia induced host-derived bone marrow cell mobilization into cardiac allografts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006 Sep;41(3):478–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circ Res. 2006 Jun 9;98(11):1414–21. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225952.61196.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda K, Fujita J. Mesenchymal, but not hematopoietic, stem cells can be mobilized and differentiate into cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction in mice. Kidney Int. 2005 Nov;68(5):1940–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leone AM, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Abbate A, Rebuzzi AG, Giovannini S, et al. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived stem cells after myocardial infarction and left ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 2005 Jun;26(12):1196–204. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shintani S, Murohara T, Ikeda H, Ueno T, Honma T, Katoh A, et al. Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001 Jun 12;103(23):2776–9. doi: 10.1161/hc2301.092122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelmann MG, Theiss HD, Hennig-Theiss C, Huber A, Wintersperger BJ, Werle-Ruedinger AE, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cell mobilization induced by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after subacute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing late revascularization: final results from the G-CSF-STEMI (Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction) trial. Journal Of The American College Of Cardiology. 2006 Oct 17;48(8):1712–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, Lahav M, Peled A, Habler L, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4. Nat Immunol. 2002 Jul;3(7):687–94. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamoto A, Tkebuchava T, Yamaguchi J, Nishimura H, Yoon YS, Milliken C, et al. Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2003 Jan 28;107(3):461–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046450.89986.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bittira B, Shum-Tim D, Al-Khaldi A, Chiu RC. Mobilization and homing of bone marrow stromal cells in myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003 Sep;24(3):393–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badorff C, Brandes RP, Popp R, Rupp S, Urbich C, Aicher A, et al. Transdifferentiation of blood-derived human adult endothelial progenitor cells into functionally active cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 2003 Feb 25;107(7):1024–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051460.85800.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshioka T, Ageyama N, Shibata H, Yasu T, Misawa Y, Takeuchi K, et al. Repair of infarcted myocardium mediated by transplanted bone marrow-derived CD34+ stem cells in a nonhuman primate model. Stem Cells. 2005 Mar;23(3):355–64. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nor JE, Christensen J, Mooney DJ, Polverini PJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated angiogenesis is associated with enhanced endothelial cell survival and induction of Bcl-2 expression. Am J Pathol. 1999 Feb;154(2):375–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou L, Ma W, Yang Z, Zhang F, Lu L, Ding Z, et al. VEGF165 and angiopoietin-1 decreased myocardium infarct size through phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and Bcl-2 pathways. Gene Ther. 2005 Feb;12(3):196–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenger RH. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2-sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2-regulated gene expression. Faseb J. 2002 Aug;16(10):1151–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0944rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia: role of the HIF system. Nat Med. 2003 Jun;9(6):677–84. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, Natarajan L, Kelly BD, Ye SQ, et al. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood. 2005 Jan 15;105(2):659–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okuyama H, Krishnamachary B, Zhou YF, Nagasawa H, Bosch-Marce M, Semenza GL. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells is dependent on hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 2006 Jun 2;281(22):15554–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu M, Wang Y, Hirai K, Ayub A, Ashraf M. Calcium preconditioning inhibits mitochondrial permeability transition and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001 Feb;280(2):H899–908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadjantonakis AK, Gertsenstein M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Nagy A. Generating green fluorescent mice by germline transmission of green fluorescent ES cells. Mech Dev. 1998 Aug;76(1–2):79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu M, Wani M, Dai Y-S, Wang J, Yan M, Ayub A, et al. Differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells into the cardiac phenotype requires intercellular communication with myocytes. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2658–65. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145609.20435.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crisostomo PR, Wang M, Wairiuko GM, Morrell ED, Terrell AM, Seshadri P, et al. High passage number of stem cells adversely affects stem cell activation and myocardial protection. Shock. 2006 Dec;26(6):575–80. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235087.45798.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu M, Uemura R, Dai Y, Wang Y, Pasha Z, Ashraf M. In vitro and in vivo effects of bone marrow stem cells on cardiac structure and function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007 Feb;42(2):441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torella D, Rota M, Nurzynska D, Musso E, Monsen A, Shiraishi I, et al. Cardiac stem cell and myocyte aging, heart failure, and insulin-like growth factor-1 overexpression. Circ Res. 2004 Mar 5;94(4):514–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117306.10142.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitta K, Day RM, Ikeda T, Suzuki YJ. Hepatocyte growth factor protects cardiac myocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001 Oct 1;31(7):902–10. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi M, Li TS, Suzuki R, Kobayashi T, Ito H, Ikeda Y, et al. Cytokines produced by bone marrow cells can contribute to functional improvement of the infarcted heart by protecting cardiomyocytes from ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 Aug;291(2):H886–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00142.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang YL, Zhao Q, Zhang YC, Cheng L, Liu M, Shi J, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation induce VEGF and neovascularization in ischemic myocardium. Regul Pept. 2004 Jan 15;117(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu HX, Li GS, Jiang H, Wang J, Lu JJ, Jiang W, et al. Implantation of BM cells transfected with phVEGF165 enhances functional improvement of the infarcted heart. Cytotherapy. 2004;6(3):204–11. doi: 10.1080/14653240410006013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gora-Kupilas K, Josko J. The neuroprotective function of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) Folia neuropathologica/Association of Polish Neuropathologists and Medical Research Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences. 2005;43(1):31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(12):5510–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallio PJ, Pongratz I, Gradin K, McGuire J, Poellinger L. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha: posttranscriptional regulation and conformational change by recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(11):5667–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimbro KS, Simons JW. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in human breast and prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006 Sep;13(3):739–49. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mabjeesh NJ, Escuin D, LaVallee TM, Pribluda VS, Swartz GM, Johnson MS, et al. 2ME2 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis by disrupting microtubules and dysregulating HIF. Cancer Cell. 2003 Apr;3(4):363–75. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagen T, D’Amico G, Quintero M, Palacios-Callender M, Hollis V, Lam F, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration by the anticancer agent 2-methoxyestradiol. Biochemical And Biophysical Research Communications. 2004 Sep 24;322(3):923–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and the molecular physiology of oxygen homeostasis. J Lab Clin Med. 1998 Mar;131(3):207–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brahimi-Horn C, Berra E, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia: the tumor’s gateway to progression along the angiogenic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2001 Nov;11(11):S32–6. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semenza G. Signal transduction to hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002 Sep;64(5–6):993–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996 Sep;16(9):4604–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tacchini L, Fusar-Poli D, Bernelli-Zazzera A. Activation of transcription factors by drugs inducing oxidative stress in rat liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002 Jan 15;63(2):139–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00836-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gray MJ, Zhang J, Ellis LM, Semenza GL, Evans DB, Watowich SS, et al. HIF-1alpha, STAT3, CBP/p300 and Ref-1/APE are components of a transcriptional complex that regulates Src-dependent hypoxia-induced expression of VEGF in pancreatic and prostate carcinomas. Oncogene. 2005 Apr 28;24(19):3110–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung JE, Lee HG, Cho IH, Chung DH, Yoon SH, Yang YM, et al. STAT3 is a potential modulator of HIF-1-mediated VEGF expression in human renal carcinoma cells. Faseb J. 2005 Aug;19(10):1296–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3099fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]