Abstract

In the absence of clear guidelines on suicide prevention there is a pressing need to translate existing and future evidence into policy. Suicide is a behaviour, not a diagnosis, and has diverse underlying pathologies. Interventions have differential effects in specific risk groups, which may include paradoxical increases in risk. For these reasons, policy makers may need to abandon the goal of one treatment for all and focus on the distinct subgroups of patients at risk when selecting, evaluating and implementing preventive interventions. This has implications for the design of future research, but has the potential to increase the utility and cost-effectiveness of the data available, thereby benefiting policy makers, clinicians and patients.

INTRODUCTION

The most recent systematic review of interventions for the prevention of suicide1 demonstrates a lack of evidence for the effectiveness for any additional psychosocial intervention following an act of self harm in preventing subsequent suicide. This comes eight years after a major review of interventions to prevent repetition of deliberate self harm reached similarly dispiriting conclusions.2 Establishing an effective means of preventing suicide at the primary or secondary care level remains ill-defined despite pressures to reduce suicide rates further3 and a climate where psychiatric services are increasingly judged by their performance in reaching these targets. In the absence of any clear benefit from the options evaluated to date, attempts have been made to fill the policy gap with short-term solutions,4 consensus opinion5 or fragmented guidance.6,7 Consequently local services remain patchy and poorly organized, a situation that is extremely discomforting given the size of the problem.8

Crawford's team point out that despite suicide data on a population of 3918 subjects, their meta-analysis lacked statistical power, but also suggest that the weakness of the existing evidence highlights a need to concentrate future research on population-based strategies. Whilst certain public health policies have shown effectiveness, for example in limiting availability of means and media influences and in improving the detection and treatment of mental illness,9 much research into strategies for high-risk groups has been hampered by the methodological problems outlined in this article.10 If these difficulties could be surmounted, interventions in primary and secondary care might well emerge as effective strategies, finally allowing clinicians to practice evidence-based suicide prevention.

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN SUICIDOLOGY

Most immediately striking as a methodological challenge is the fact that suicide is a rare outcome, requiring large trials in order to detect clinically significant reductions in the base rate. Behavioural characteristics of the study population exacerbate this problem by tending towards high attrition rates. Additional problems result from the often necessary use of multi-centre trials where effect sizes may be underestimated due to contamination in centres where there is little difference between ‘treatment as usual’ (TAU) and the intervention on trial.11 A fourth area of difficulty is the diversity of the population at risk, the characteristics of which vary according to age, gender, ethnic group, diagnosis and behaviour. This group comprises individuals with overlapping diagnoses of depressive disorders, bipolar affective disorder, substance misuse problems, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and different permutations of personality disorders and traits, or those with no diagnosis at all. The presence or absence of personality disorder is a strong predictor of the risk of self harm and its frequency, but regardless of diagnosis the interpersonal problems and intentions underlying every act of self harm are varied and extremely unpredictable.12 This is particularly true where cultural factors come into play and in a society where the ethnic mix is evolving rapidly. Herein lies the crux of the problem: suicide and deliberate self harm are behaviours, not diagnoses, and have diverse underlying pathologies. With such a heterogeneous population at risk a goal of one treatment for all seems unrealistic, and policy-focused research design should ideally reflect this.

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND THE IMPORTANCE OF SPECIFIC SUBGROUP RESULTS

These problems in the design of research protocols may explain many trials of interventions to reduce suicidal behaviour that have produced negative findings,11,13-18 although clearly another explanation is that the interventions were simply ineffective. A small number of trials have shown positive findings, but such trials are often dismissed as being of limited generalizability.19-28 Where syntheses of results by meta-analysis have attempted to further utilize these data sets there has been inadequate power to detect differences, and consequently calls have been made to conduct larger-scale trials of interventions shown to be of possible benefit in small trials.1 Although this might provide adequate power, the research endeavour would only be of value if its study population shared similar characteristics to those shown to benefit from the intervention in smaller trials. When evaluated in a mixed population, any potential treatment effect could run the risk of becoming diluted or of differential treatment effects cancelling each other out, yielding yet more negative results.

Support for this idea comes from subgroup analysis of negative studies which reveal significant (or near-significant) reductions or indeed paradoxical increases in risk for specific groups following an intervention.14,18 The observation that certain treatment plans serve to positively reinforce self-harming behaviour is well recognized, particularly in patients with borderline personality disorder.29 Evidence is also emerging that pharmacological treatments can increase risk in certain groups at key temporal stages in treatment.30,31 Within such a mixed patient population, differential responses to treatments are hardly surprising and suggest it is more prudent, more ethical and a more cost-effective use of research funds to focus on selected patient subgroups in the evaluation and implementation of interventions.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

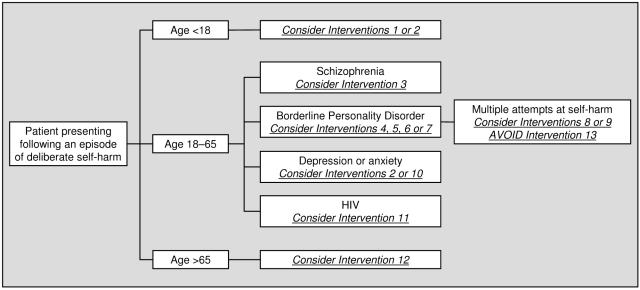

Future trials face the challenge of being able to generate adequate statistical power whilst maintaining tightly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only by achieving this can researchers identify precisely which interventions are best suited to specific patient groups. In gradually building up a jigsaw of effective interventions matched to target groups, a series of clinical guidelines could emerge. Conceptually organized as a decision tree, and amenable to use in a system of stepped care, clinicians would be able to identify evidence-based interventions suited to the demographic, diagnostic and behavioural characteristics of each patient encountered (Figure 1). A young female patient who has taken the fifth in a series of overdoses is likely to be offered an intervention very different to that identified as appropriate for a severely depressed male in his late 60s, with worsening osteoarthritis, who has never self-harmed. Where the evidence was available, guidelines could also include data on cost-effectiveness and acceptability, as well as alerts for any interventions causing increased risk for that subgroup.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a decision tree used to match interventions to the demographic, diagnostic and behavioural characteristics of self-harming patients

At times suicidologists have exhorted researchers to ‘think big’ in establishing large-scale, long-term and rigorously constructed trials.10 Given the intrinsic peculiarities of suicidality, however, this may be encouraging further cost-ineffective research unless rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria define a homogenous study population. Although this inevitably increases the operational costs of a study it also increases the likelihood of yielding results that can be translated into policy. Other advantages of this subgroup approach include the addressing of inequalities in health by targeting effective interventions at marginalized groups, for example those with personality disorders or those newly released from prison, and the encouragement of research into interventions appropriate to refugees and ethnic minorities. This upholds one of the rights to health, namely universal access to good quality health care, by improving consistency of care and promoting distributive justice.32

There are other ways of increasing the proportion of research information useful to policy makers in suicide prevention. Studies using outcome measures wider than data on completed suicides or acts of self harm are often easier to design and conduct (both ethically and methodologically) and can also help identify treatments that reduce risk factors for self harm. This is relevant both because any intervention shown to reduce suicidal ideation and behaviour may reasonably be thought to have an impact on reducing morbidity and preventing completed suicide, and because of the public health impact of deliberate self harm per se. Acts of self harm can be as costly as suicide in terms of loss of productive life and family disruption, but government targets do not reflect this. Intermediate outcomes such as reductions in scores of depression or hopelessness offer utility as proxy measures both in terms of study design and in their application to clinical settings. Treatments that have been demonstrated to reduce scores on scales of psychiatric morbidity could be applied to the management of patient groups at risk of self harm as well as to those who have actually self-harmed.33 Even interventions that are shown to impact on more distal variables like quality of life or personality disorder severity scales may have a role in guiding management and promoting further research into their impact on repetition of deliberate self harm.34

A broader choice of study type could increase the generalizability of findings, particularly given that randomized controlled trials, usually regarded as the gold standard in evidence-based research, may not always reflect clinical reality. Observational studies have often been a valuable complement to evidence amassed in randomized trials35 and may have been under-utilized, especially given their suitability for rare conditions and exposures and their ethical superiority in certain situations. Finally, if cost-effectiveness studies and patient acceptability measures were factored into all evaluations, decision-making could take into account the scarce resources allocated to mental health and acknowledge issues around treatment concordance. In the absence of demonstrated cost-effectiveness data, some would argue that a reliance on cost-minimization analysis or inferences made from cost-effectiveness acceptability curves is an adequate basis for justifying use of public funds, particularly when the cost of services for self harm are so great.17 Although the policy ideal is to implement only those policies that are cost-effective, social values are also important, particularly when the tools of economic analysis can be quite blunt.36

CONCLUSIONS

With such a heterogeneous population as the province for suicide prevention it is not surprising that individual interventions are likely to be differentially effective in defined subgroups. The goal of one treatment for all may be unrealistic and this has implications for current policy and for future research design. The research base for evidence-based policy in suicide prevention is likely to consist of a whole series of trials which manage to fulfil the often-conflicting aims of concentrating on defined populations whilst also achieving adequate power (of at least n=250). Where effective interventions are identified these can be added to a series of guidelines linked to the specific patients predicted to show the most benefit. In clinical practice this series of guidelines might be presented as a decision tree, guiding clinicians towards the specific characteristics of their patient and any interventions matched to them. This incremental and comprehensive approach has the advantage of catering to the diversity of the population at risk, is supported by health policy theory, and matches recommendations made in the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness.6 A targeted decision tree approach simplifies what is a highly complex problem and allows research findings to be more easily translated into policy.

Future empirical work focusing on the subgroups that comprise that population at risk of suicide and deliberate self harm is eagerly anticipated. It provides a basis on which evidence-based guidelines can be made available to practicing clinicians who can then be more confident about minimizing risk when assessing individual patients. Areas where knowledge is still awaited can be filled in temporarily by guidelines based on expert consensus, providing these have sufficient transparency and reliability.37 With the publication of each new data set, established clinical guidelines can be continually revised and refined in the light of improved evidence on cost, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, with the potential to reconcile factors such as local acceptability, feasibility and resource availability.

Competing interests None declared.

Guarantor AP.

Contributorship AP is the sole contributor.

Acknowledgment I am grateful to Professor Peter Tyrer of Imperial College for his comments.

References

- 1.Crawford MJ, Thomas O, Khan N, Kulinskaya E. Psychosocial and pharmacological interventions following deliberate self harm: systematic review of their efficacy in preventing subsequent suicide. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190: 11-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawton K, Arensman E, Townsend E, et al. Deliberate self harm: systematic review of efficacy of psychosocial and pharmacological treatments in preventing repetition. BMJ 1998;317: 441-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England. London: HMSO, 2002

- 4.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. The Short-Term Physical and Psychological Management and Secondary Prevention of Self Harm in Primary and Secondary Care. London: NICE, 2004. Available at www.nice.org.uk [PubMed]

- 5.Isacsson G, Rich CL. Management of patients who deliberately self harm themselves. BMJ 2001;322: 213-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health. National Service Framework for Mental Health: Modern Standards and Service Models. London: HMSO, 1999

- 7.Department of Health. Safety First: Five Year Report of the Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. London: HMSO, 2001

- 8.World Health Organization. World Health Report. Geneva: WHO, 2001

- 9.Hawton K. Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour: From Science to Practice. Oxford: OUP, 2005

- 10.De Leo D. Why are we not getting any closer to preventing suicide? Br J Psychiatry 2002;181: 372-4 [Editorial] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyrer P, Thompson S, Schmidt U, et al. Randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self harm: the POPMACT study. Psychol Med 2003;33: 969-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fagin L. Repeated self-injury: perspectives from general psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2006;12: 193-201 [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Sande R, Buskens E, Allart E, van der Graaf Y, van Engeland H. Psychosocial intervention following suicide attempt: a systematic review of treatment interventions. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96: 43-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Sande R, van Rooijen L, Buskens E, et al. Intensive in-patient and community intervention versus routine care after attempted suicide. A randomised controlled intervention study. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171: 35-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans MO, Morgan HG, Hayward A, Gunnell DJ. Crisis telephone consultation for deliberate self harm patients: effects on repetition. Br J Psychiatry 1999;175: 23-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennewith O, Stocks N, Gunnell D, Peters TJ, Evans MO, Sharp DJ. General practice based intervention to prevent repeat episodes of deliberate self harm: cluster randomised controlled trial BMJ 2002: 324: 1254-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byford S, Knapp M, Greenshields J, et al. POPMACT Group. Cost-effectiveness of brief cognitive therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self harm: a decision-making approach Psychol Med 2003;33: 977-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans J, Evans M, Morgan HG, Hayward A, Gunnell D. Crisis card following self harm: 12 month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187: 91-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salkovskis PM, Atha C, Storer D. Cognitive-behavioural problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide—a controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1990;157: 871-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verkes RJ, Van der Mast RC, Hengeveld MW, Tuyl JP, Zwinderman AH, Van Kempen GM. Reduction by paroxetine of suicidal behaviour in patients with repeated suicide attempts but not major depression. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155: 543-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guthrie E, Kapur N, Mackway-Jones K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of brief psychological intervention after deliberate self poisoning. BMJ 2001;323: 135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood A, Trainor G, Rothwell J, Moore A, Harrington R. Randomized trial of group therapy for repeated deliberate self harm in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40: 1246-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motto JA, Bostrum AG. A randomised controlled trial of post-crisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52: 828-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, de Ridder MAJ, van den Brink W. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182: 135-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294: 563-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter GL, Clover K, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, D'Este C. Postcards from the Edge Project: randomised controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self-poisoning. BMJ 2005;331: 805-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaiva V, Vaiva V, Ducrocq F, et al. Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: randomised controlled study. BMJ 2006;332: 1241-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson K, Norrie J, Tyrer P, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: results from the borderline personality disorder study of cognitive therapy (BOSCOT) trial. J Personal Disord 2006;20: 450-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comtois KA. A review of interventions to reduce the prevalence of parasuicide. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53: 1138-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez C, Rietbrock S, Wise L, et al. Antidepressant treatment and the risk of fatal and non-fatal self harm in first episode depression: nested case-control study. BMJ 2005;330: 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Kopp A, Redelmeier DA. The risk of suicide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163: 813-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999;318: 527-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skegg K. Self harm. Lancet 2005;366: 1471-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy versus transference-focused psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;63: 649-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall WD. How have the SSRI antidepressants affected suicide risk? Lancet 2006;367: 1959-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coast J. Is economic evaluation in touch with society's health values? BMJ 2004;329: 1233-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raine R, Sanderson C, Black N. Developing clinical guidelines: a challenge to current methods. BMJ 2005;331: 631-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]