Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a disease that is characterized by fibroblast accumulation and activation in the distal airspaces of the lung. We hypothesized that fibrotic lung fibroblasts migrate/invade across basement membranes by integrin-mediated mechanisms as a means of entering alveoli. We demonstrate that in lung fibroblasts derived from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, fibronectin signaling is both necessary and sufficient for basement membrane migration/invasion across basement membranes. This effect is mediated through the α5β1 integrin because blockade of fibronectin-α5 integrin ligation attenuated this response. In contrast, ligation of α4β1 integrin inhibits basement membrane invasion by normal lung fibroblasts but not by fibrotic lung fibroblasts. This phenotypic difference is not related to surface expression of the α4β1 integrin, as demonstrated by flow cytometry. In normal lung fibroblasts but not in fibrotic lung fibroblasts, we show that ligation of α4β1 integrin induces a significant increase in phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) activity. Fibrotic lung fibroblasts express constitutively less PTEN mRNA and protein as well as phosphatase activity in comparison to normal lung fibroblasts. Together, these data suggest that a loss of α4β1 signaling via PTEN confers a migratory/invasive phenotype to fibrotic lung fibroblasts. Furthermore, this study implicates a loss of PTEN function in the pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: pulmonary fibrosis, extracellular matrix, fibronectins, cell movement

Pulmonary fibrosis is the end result of injury to the lung (1). Antecedent injuries to the lung may be recognized, as with chemotherapy (2), collagen vascular disease (3), or inhalational injury (4). However, in the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, the inciting insult remains unidentified (5). Of the various idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) has the worst prognosis and is the histologic pattern that is associated with the clinical entity known as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). UIP/IPF is characterized by a lower lobe predominant, subpleural deposition of scar tissue with a relative paucity of inflammatory cells (6). Although most fibrotic zones are composed of “old,” relatively acellular collagen bundles, small aggregates of intraalveolar myofibroblasts and fibroblasts have been identified in “fibroblastic foci” of UIP (7). Myofibroblasts within fibroblastic foci are the predominant source of secreted collagen (8). Intraalveolar fibroblasts are found in proximity to both collagen- and fibronectin-rich areas in pulmonary fibrosis (9), suggesting a possible role for extracellular matrix (ECM) signaling in the pathophysiology of UIP (10).

Integrins are the major receptors for ECM proteins (11) and are comprised of two noncovalently linked subunits, termed α and β, that together form heterodimer pairs. The α5β1 integrin is the major fibronectin receptor on a variety of cells (12) and is the best characterized of the fibronectin receptors. However, other integrins bind and transduce signals from fibronectin, such as α3β1, α4β1, α8β1, and αvβ3 (13). The α4 integrin subunit is somewhat distinct because it recognizes the type III connecting segment of fibronectin containing the connecting segment-1 (CS-1) domain (14). Ignatoski and colleagues showed that the oncogene ERBB2 (HER-2/neu), when overexpressed in human mammary epithelial cells, induces an invasive phenotype that is correlated with downregulation of cell surface expression of the α4β1 integrin (15), suggesting that α4β1 integrin may negatively regulate the invasive phenotype. Conversely, the α5β1 integrin promotes a migratory and invasive cellular phenotype when transducing signals from functional domains of fibronectin, such as the 110- to 120-kD central cell-binding domain or the “synergy sequence” pentapeptide Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn (16, 17). Together, these data suggest that α4β1 and α5β1 integrin signaling by fibronectin might differentially mediate migratory and/or invasive phenotypes.

The tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10/mutated in multiple advanced cancers-1/transforming growth factor-β–regulated epithelial cell–enriched phosphatase (hereafter referred to as PTEN) is a dual-specificity protein and lipid phosphatase that uses phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate as a physiologic substrate (18). PTEN mutations have been identified in a variety of malignancies, and loss of PTEN activity is associated with the invasive and metastatic potential of tumors (19). Additionally, PTEN modulates behavior of nontransformed cells because loss of PTEN expression is associated with migration/invasion of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis (20). PTEN plays a major role in apoptosis when cells are removed from attachment to matrix proteins (anoikis) (21), suggesting that PTEN activity is regulated through ECM interactions.

Because ECM likely influences fibroblast migration and/or invasion across disrupted basement membranes to enter the alveolar space, we addressed the hypothesis that α4β1 and α5β1 integrins regulate the migratory/invasive fibroblast phenotype. We further hypothesized that decreased PTEN expression and/or activity would account for the increased migratory/invasive phenotype in fibrotic lung fibroblasts (FLFs) compared with normal lung fibroblasts (NLFs). Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (22).

METHODS

Cells

FLFs were obtained from patients undergoing surgical lung biopsy for diagnosis of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (see the online supplement for additional detail). Control NLFs were obtained from patients undergoing thoracic surgery for nonfibrotic lung diseases. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. FLFs were only used from patients in whom a pathologic diagnosis of UIP was subsequently made. Normal human fetal lung fibroblasts (IMR-90) were from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). All studies were performed using cultured fibroblasts between the fourth and ninth passage. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, fungizone, and N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-ethane sulfonic acid.

Reagents

The Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn peptide and fibronectin-depleted FCS were prepared as described (23). Human plasma fibronectin and the CS-1 fibronectin fragment were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The 110-kD fibronectin fragment was from U.S. Biological (Swampscott, MA). Function-blocking antibodies to the α5 integrin subunit (clone P1D6) and the α4 integrin subunit (clone P1H4) were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA).

Migration/Invasion Assays

Sea urchin-ECM invasion assays were performed and quantitated as previously described by Livant and colleagues (24). Matrigel transwell assays were performed and quantitated according to the method of Tamura and colleagues (25). Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion before use in assays. In all cases, cell viability exceeded 90%.

Flow Cytometry

NLFs and FLFs were harvested with trypsin-versene (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) and washed twice in cold buffer (FA Buffer; Difco, Detroit, MI). Cells were resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in FA buffer and were incubated with R-phycoerythrin–conjugated mouse anti-human α4 integrin (Cymbus Biotechnology, Chandlers Ford, Hants, UK), fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated mouse anti-human α5 integrin (Cymbus Biotechnology) or the appropriately labeled IgG control antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) on ice. Cells were washed in FA buffer twice and fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin. Fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry on an EPICS Profile II flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics Inc., Miami, FL).

PTEN Immunoprecipitation

Serum-starved fibroblasts were treated with CS-1 peptide for 18 hours, washed twice, and lysed in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and orthovanadate. Total protein concentrations were determined using the DC Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Immunoprecipitation was performed using Protein G-PLUS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-PTEN antibody (clone A2B1; Chemicon).

PTEN Phosphatase Assay

PTEN immunoprecipitates were assessed for phosphatase activity using the method of Georgescu and colleagues (26). Free phosphate was determined on a colorimeter by measuring absorbance at 630 nm. Absorbances were compared with a standard curve generated from known free phosphate concentrations. Results were reported as picomoles of free phosphate released (± SEM).

Semiquantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed on an ABI Prism 7000 SDS thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primer and probe combinations were created using Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) and were based on GenBank sequences XM_034848 (human PTEN) and M10277 (human β-actin). Relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative cycle-threshold method (27).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis under reducing conditions was performed on whole-cell lysates prepared as described previously here. Samples were boiled for 5 minutes, resolved on an 8–16% gradient gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked, followed by incubation with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase–labeled secondary antibody followed by chemiluminescence detection (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Densitometry of visualized bands was performed using Image J software (version 1.3, National Institutes of Health).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat 3.05 (San Diego, CA). Differences between groups were evaluated using Student’s t test. For multiple comparisons, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s post-test analysis was used. Data were considered significant if p < 0.05. Results were plotted using GraphPad Prism 3.02 (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Plasma Fibronectin Induces FLF Migration across Basement Membranes

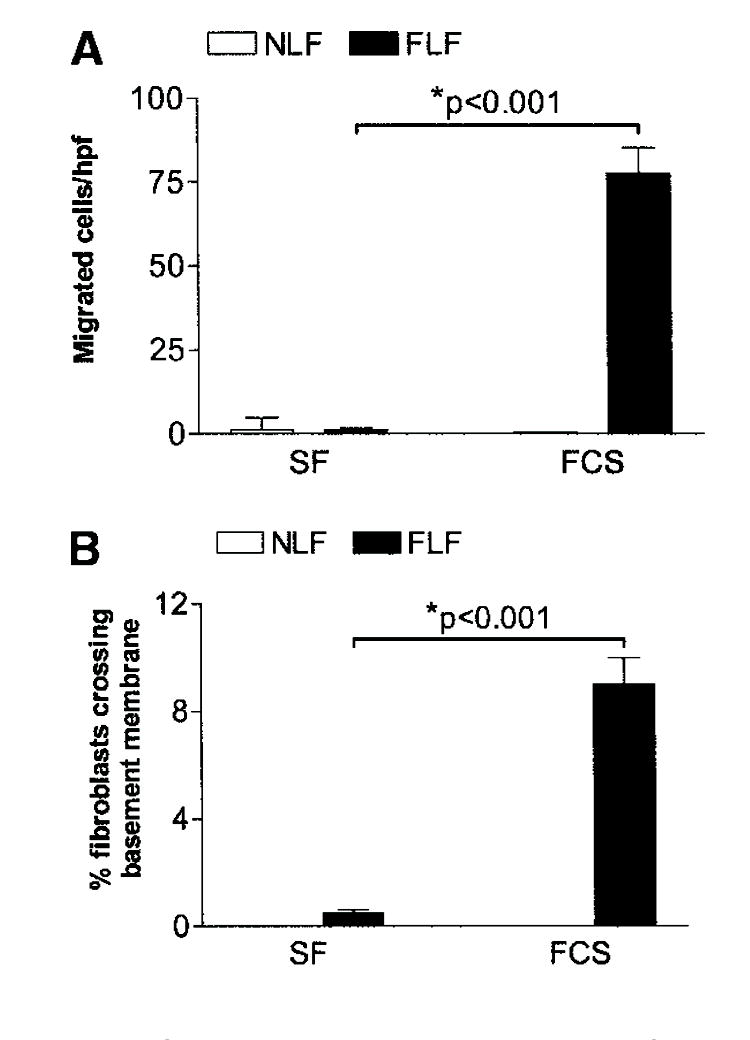

We hypothesized that FLF would migrate across basement membranes as a mechanism to enter alveolar spaces. To test this hypothesis, we isolated lung fibroblasts from five patients each with UIP or without fibrotic lung disease and assessed their ability to migrate across basement membranes. We first evaluated basement membrane migration/invasion in the presence of serum-free media or 10% FCS to determine the contribution of serum to the migratory/invasive phenotype. We observed that FLFs crossed basement membranes significantly greater in the presence of serum in both the Matrigel transwell assay (Figure 1A) and the sea urchin-ECM assay (Figure 1B). NLFs demonstrated minimal basement membrane migration/invasion under either condition (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fibrotic lung fibroblasts (FLFs), but not normal lung fibroblasts (NLFs), migrate across basement membranes in the presence of serum. (A) Matrigel transwell assay. NLFs (open bars) and FLFs (closed bars) were stimulated with serum-free (SF) media or media containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cell migration is reported as the mean number of cells/high-power field (hpf) ± SEM. (B) Sea urchin extracellular matrix invasion assay. NLFs (open bars) and FLFs (closed bars) were stimulated with SF media or media containing 10% FCS. Cell invasion is reported as the mean percentage of cells invading basement membranes ± SEM. FLFs migrated across basement membranes in the presence of serum, whereas SF media resulted in minimal cell migration. Data are representative results from experiments with fibroblasts from five patients in each group. Each patient’s fibroblasts were assessed at least twice in each assay.

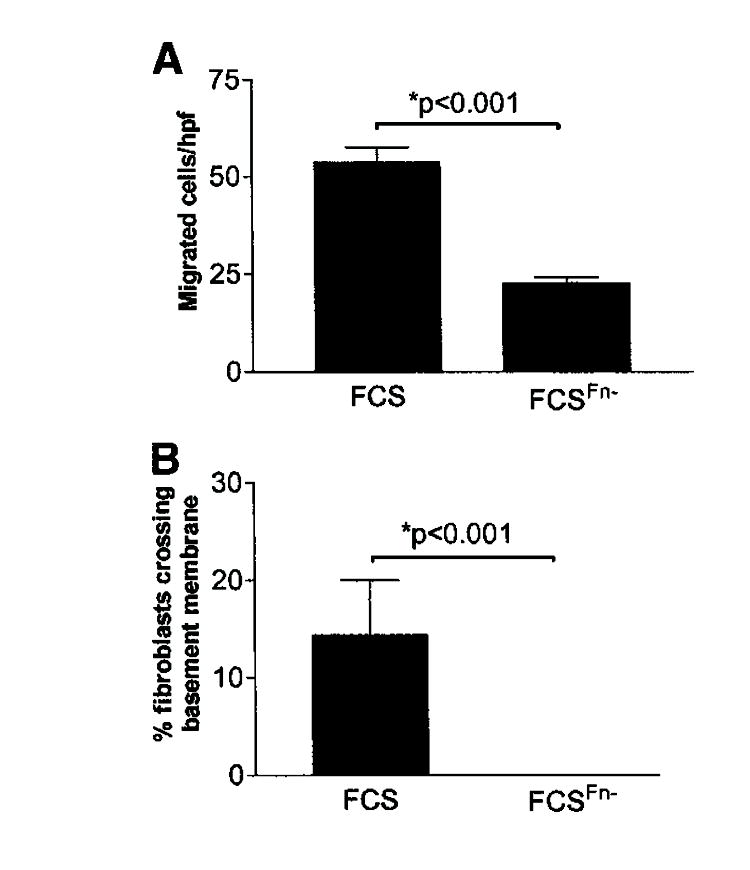

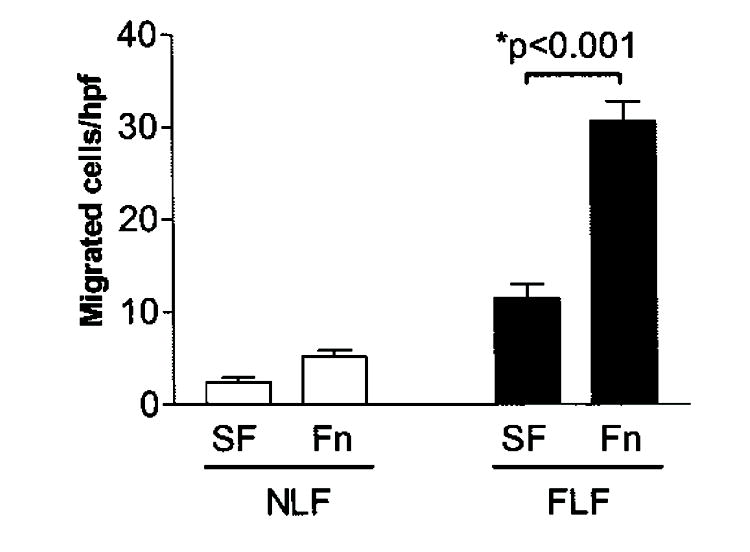

Fibronectin promotes an invasive phenotype in cancer cells. Therefore, we sought to determine the contribution of fibronectin to the basement membrane migratory/invasive phenotype of FLFs. To address this, we evaluated basement membrane migration/invasion by FLFs in the presence of 10% FCS or fibronectin-depleted FCS. We found significant migration across basement membranes by FLFs in the presence of 10% FCS, but not in the presence of fibronectin-depleted FCS, in both the Matrigel transwell assay (Figure 2A) and the sea urchin-ECM assay (Figure 2B). NLFs crossed basement membranes to a much lower degree under each condition (data not shown). This finding suggests that plasma fibronectin is necessary to promote the full migratory/invasive phenotype in FLFs. We then assessed basement membrane migration/invasion in the presence or absence of fibronectin alone to determine whether fibronectin is sufficient to induce basement membrane invasion by fibroblasts. Under these conditions, intact plasma fibronectin was sufficient to induce basement membrane migration/invasion by FLFs (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Fibronectin is necessary for full migration across basement membranes by FLFs. (A) Matrigel transwell assay. FLFs were stimulated to cross basement membranes in the presence of 10% FCS or 10% FCS that had been depleted of fibronectin (FCSFn−). Cell migration is reported as the mean number of cells/hpf ± SEM. (B) Sea urchin extracellular matrix invasion assay. FLFs were stimulated with FCS or FCSFn−. Cell invasion is reported as the mean percentage of cells invading basement membranes ± SEM. FLFs invaded basement membranes significantly in the presence of serum. FCSFn− induced no significant basement membrane invasion above that seen for serum-free conditions (data not shown). Data are representative results from experiments with fibroblasts from five patients in each group. Each patient’s fibroblasts were assessed at least twice in each assay.

Figure 3.

Fibronectin is sufficient to induce migration across basement membranes by FLFs. Fibroblast migration was assessed by the Matrigel transwell assay using SF media or SF media to which 4-μg/ml plasma fibronectin (Fn) had been added. Cell migration is reported as mean number of cells per hpf (± SEM). The addition of Fn did not induce increased invasion in NLFs. Data are representative results from experiments with fibroblasts from five patients in each group. Each patient’s fibroblasts were assessed at least twice in each assay.

The α5β1 Integrin Mediates the Migratory Phenotype of Fibroblasts after Ligation with a Synergy Sequence-containing Fragment of Intact Plasma Fibronectin

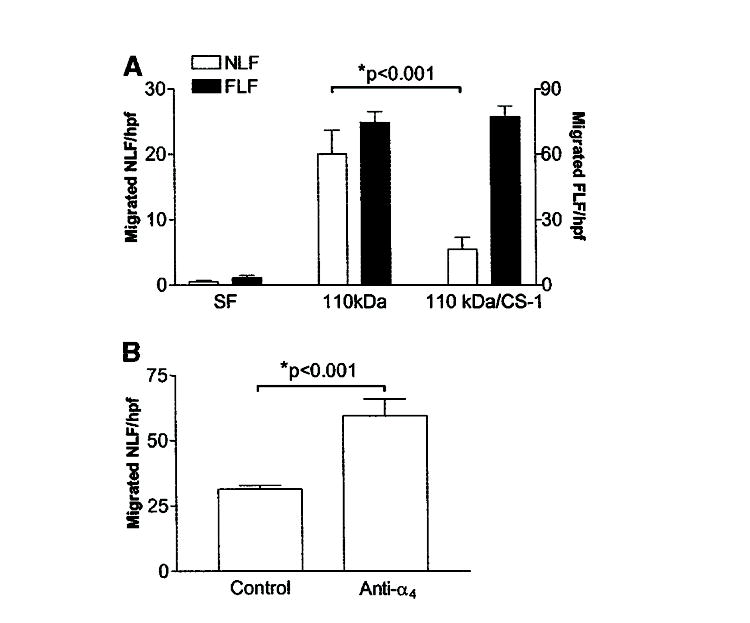

Based on the findings that fibronectin was necessary and sufficient to induce basement membrane invasion by FLFs, we next sought to determine the contribution of the α5β1 integrin to the migratory/invasive phenotype. We performed basement membrane migration/invasion assays on NLFs and FLFs in the presence or absence of the 110-kD central cell-binding domain of fibronectin, an α5β1 integrin-specific fibronectin fragment. The 110-kD fibronectin fragment is likely more physiologically relevant than intact plasma fibronectin in UIP, where protease activity results in the degradation of fibronectin into distinct fragments. We found that the 110-kD fibronectin fragment alone was able to induce FLF migration/invasion across basement membranes (Figure 4A). Interestingly, we found that NLFs also crossed basement membranes in the presence of the 110-kD fragment (Figure 4A). These observations suggested that unopposed α5β1 integrin stimulation promotes a migratory/invasive phenotype in fibroblasts. These results strongly implicate the α5β1 integrin in promoting a migratory/invasive phenotype.

Figure 4.

Connecting segment-1 (CS-1) peptide ligation with α4β1 integrin attenuates basement membrane migration in NLFs but not FLFs. (A) Matrigel transwell assay of NLFs in response to SF media alone, SF media with the 110-kD fibronectin fragment (110 kD), or a combination of the 110 kD and CS-1 containing fibronectin fragments (110 kD/CS-1). Cell migration is reported as mean number of cells per hpf ± SEM. The CS-1 fibronectin fragment attenuates migration across basement membranes by NLFs but not by FLFs. Migration across basement membranes by FLFs was not different between the 110-kD and the 110-kD/CS-1 groups. Data are representative of experiments with fibroblasts from five patients in each group. Each patient’s fibroblasts were assessed at least twice. (B) Fibronectin-induced migration across basement membranes is inhibited by α4β1 ligation. NLFs migrated across basement membranes minimally in response to intact fibronectin when treated with nonspecific IgG (control). In the presence of anti-α4 integrin antibody, intact fibronectin induced significant fibroblast migration across basement membranes.

The α4β1 Integrin Suppresses α5β1 Integrin-mediated Basement Membrane Migration/Invasion Induced by Fibronectin

Our data show that NLFs migrate across basement membranes when α5β1 integrin ligation is unopposed (i.e., in response to the 110-kD fibronectin fragment) but not in the presence of intact fibronectin (which binds to multiple integrins), whereas FLFs cross basement membranes under either condition. This suggests that other integrin-binding domains of fibronectin may play a role in suppressing NLF migration/invasion. The α4β1 integrin recognizes the CS-1 fibronectin fragment and is thought to transduce invasion-inhibitory signals. We therefore assessed basement membrane migration/invasion of NLFs and FLFs in the presence of both the 110-kD central cell-binding domain–containing fibronectin fragment and the CS-1 fibronectin fragment. When NLFs and FLFs were stimulated with both the 110-kD fibronectin fragment and the CS-1 fibronectin fragment, we observed an inhibition of basement membrane migration/invasion induced by the 110-kD fibronectin fragment only in NLF (Figure 4A). However, the CS-1 fragment failed to inhibit basement membrane migration/invasion by FLFs induced by the 110-kD central cell-binding domain–containing fragment. These data support the possibility that disparate fibronectin signaling through the α4β1 integrin in FLFs may account for increased basement membrane migratory/invasive activity by these cells.

To demonstrate whether NLFs could migrate across basement membranes in response to plasma fibronectin, we performed Matrigel invasion/migration assays in the presence of plasma fibronectin on NLFs treated with function-blocking anti-α4 integrin subunit antibodies. We observed that NLF migration significantly increased under these conditions (Figure 4B). These data suggest that the α4β1 integrin contributes to inhibition of fibroblast migration/invasion in response to plasma fibronectin.

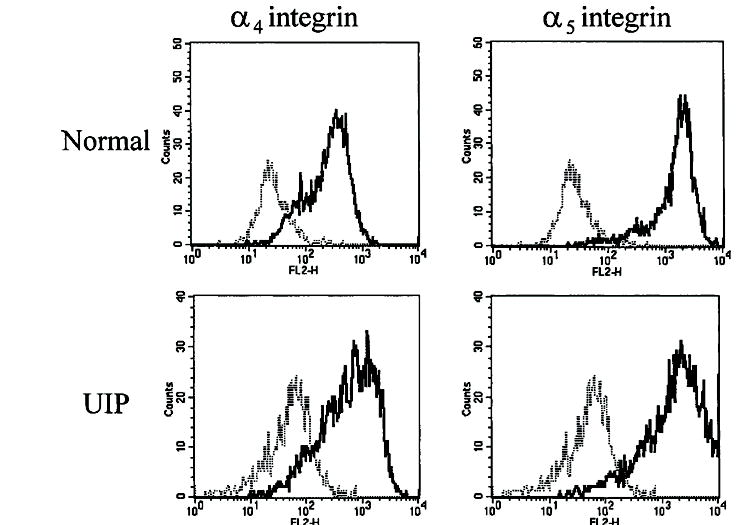

Normal Lung and FLFs Express Cell-surface α4β1 and α5β1 Integrins

To account for differences in fibronectin fragment signaling through the α4β1 and α5β1 integrins, we first assessed both NLFs and FLFs for surface expression of α4 and α5 integrin subunits. The α4 integrin subunit only forms heterodimers with the β1 and β7 integrin subunits, but β7 integrin expression is restricted to lymphocytes. In addition, the α5 integrin subunit only associates with the α1 integrin subunit. Using flow cytometry, we found that both NLFs and FLFs express the α4 and β5 integrin subunits on their surfaces (Figure 5), suggesting the phenotypic differences noted were not related to altered cell-surface expression of these fibronectin receptors. However, because both NLFs and FLFs crossed basement membranes after α5β1 integrin ligation, we hypothesized that the α4β1 integrin was capable of transducing invasion-inhibitory signals in fibroblasts. To study the signaling pathways downstream of the α4β1 integrin, we used normal human lung fibroblasts (IMR-90) that express the α4β1 and α5β1 integrins and respond similarly to NLFs in migration/invasion assays (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Cell-surface expression of the α4 and α5 integrin subunits on NLFs and FLFs. Equal numbers of each fibroblast line were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-α5 integrin antibody, R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-α4 integrin antibody, or the appropriate fluorochrome-labeled nonspecific IgG and assessed for fluorescence using flow cytometry. In all cases, each patient’s lung fibroblasts expressed both the α4 and α5 integrin subunits on the cell surface. Thin dotted lines represent nonspecific IgG staining, and solid lines represent the integrin-specific fluorescent signal. Data are representative results from experiments with fibroblasts from five patients in each group. To ensure reproducibility, each patient’s fibroblasts were assessed at least twice. UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia.

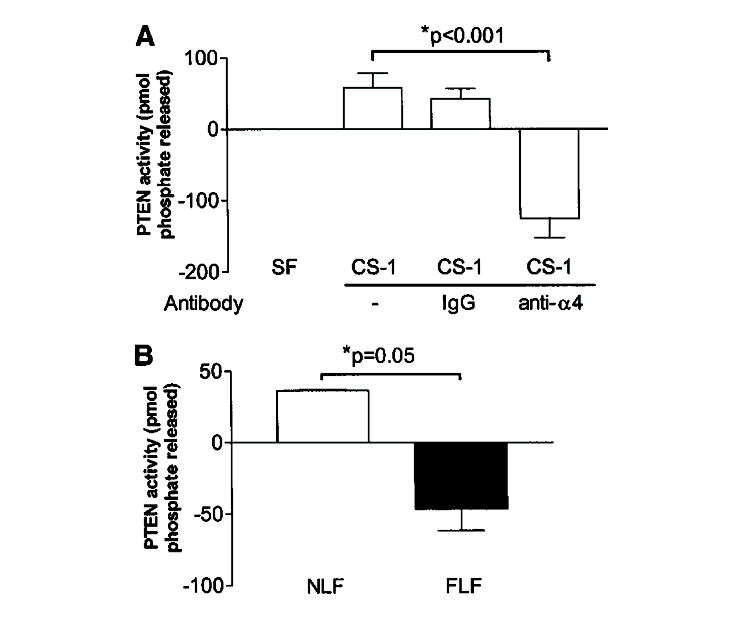

PTEN Phosphatase Activity Is Induced by Ligation of the α4β1 Integrin with the CS-1 Fibronectin Fragment

Because our initial data demonstrated a clear difference in basement membrane migratory/invasive potential between NLFs and FLFs in response to ligation of the α4β1 integrin by the CS-1 fibronectin fragment, we asked whether PTEN, a known invasion inhibitor, is activated downstream of the α4β1 integrin in NLFs. To test this possibility, IMR-90 fibroblasts were exposed to the CS-1 fibronectin fragment for varying lengths of time. Cell lysates were prepared, and PTEN was immunoprecipitated to assess total lipid phosphatase activity; PTEN phosphatase activity increased in response to CS-1 ligation in a time-dependent manner, with maximal induction of activity at 18 hours (data not shown). PTEN activity did not increase over time in culture in the absence of CS-1 ligand (data not shown); we observed that increased PTEN activity was due to α4β1 ligation because concomitant treatment of cells with function-blocking anti-α4 integrin antibody, but not control antibody, negated this response (Figure 6A). We subsequently assessed PTEN activity in NLF and FLF lines after stimulation with CS-1 peptide. Consistent with our findings for the IMR-90 cell line, NLFs demonstrated increased PTEN phosphatase activity in response to CS-1 peptide. However, FLFs demonstrated decreased PTEN phosphatase activity (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) lipid phosphatase activity is induced by CS-1 fibronectin fragment ligation of the α4β1 integrin. Human lung fibroblasts (IMR-90) were incubated for 18 hours with SF media alone, SF media containing 20-nM CS-1 peptide alone, or in the presence of nonspecific IgG or anti-α4β1 integrin antibody. Cells were assayed for PTEN activity, and results were expressed as the mean change in phosphate released (± SEM) for each condition, as compared with values obtained at baseline. PTEN lipid phosphatase activity is significantly induced by CS-1 ligation. This effect is specific for ligation of CS-1 with the α4β1 integrin. Changes in PTEN activity were not observed in the absence of ligands (data not shown). Results are representative of a duplicate set of experiments. (B) PTEN activity is induced in NLFs but decreased in FLFs in response to CS-1 peptide. NLFs (n = 5; open bar) and FLFs (n = 5; closed bar) were exposed to 20-nM CS-1 peptide, and PTEN immunoprecipitates were assayed for phosphatase activity. NLFs demonstrated increased PTEN activity, whereas FLFs decreased PTEN activity under the same conditions. Results are representative of the mean change in phosphate released by NLFs and FLFs.

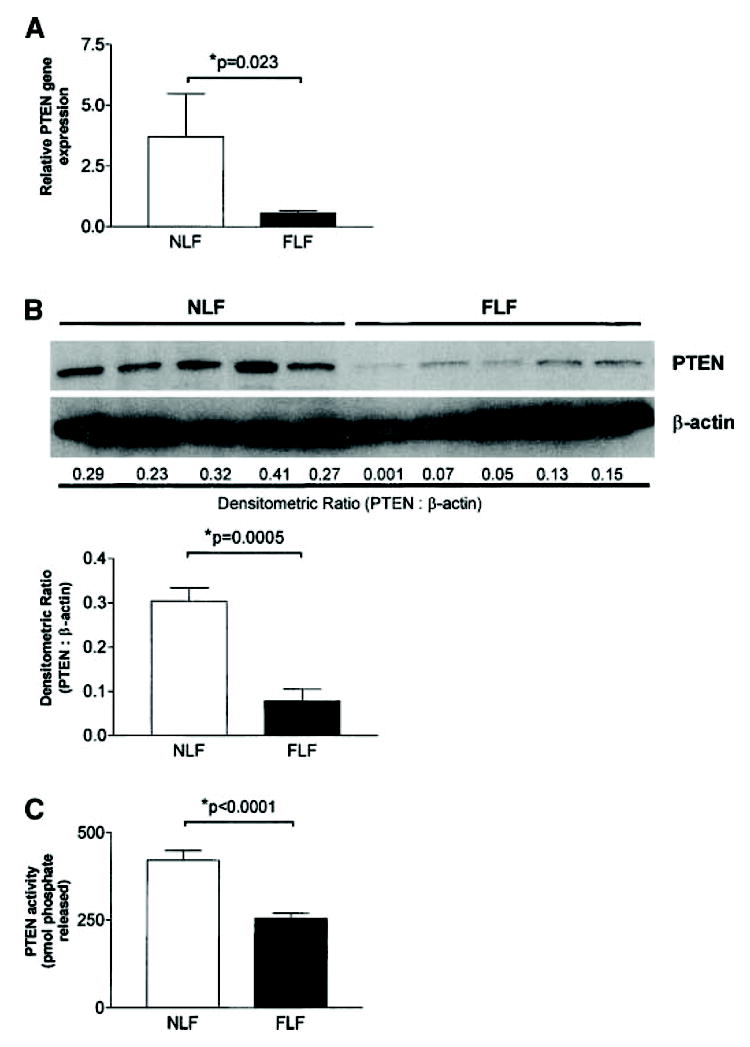

PTEN Gene and Protein Expression and Phosphatase Activity Is Constitutively Decreased in Fibroblasts from UIP Compared with NLF

Our data demonstrate that the α4β1 integrin inhibits basement membrane migration/invasion in fibroblasts through a pathway that may involve the PTEN tumor suppressor. We therefore asked whether NLFs and FLFs expressed PTEN at the mRNA and protein level. Using semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, we assessed RNA from NLFs and FLFs lines for PTEN gene expression. We found significantly decreased PTEN gene expression in FLFs compared with NLFs (p = 0.023) (Figure 7A). To determine whether the decrease in PTEN gene expression corresponded to decreased protein levels, we performed Western analysis of whole-cell lysates from both NLFs and FLFs for total PTEN expression. We observed significantly decreased PTEN protein expression from FLFs when compared with NLFs (Figure 7B). Additionally, we performed PTEN phosphatase activity assays on immunoprecipitated PTEN from both NLFs and FLFs. Consistent with these findings, we detected significantly diminished phosphatase activity of immunoprecipitated PTEN from FLFs compared with that from NLFs (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

PTEN gene and protein expression and phosphatase activity are constitutively diminished in FLFs compared with NLFs. (A) Semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for PTEN was performed on 100-ng total RNA obtained from NLFs and FLFs. Constitutive PTEN gene expression is significantly diminished in FLFs as compared with NLFs (p = 0.023). (B) Western blot analysis for PTEN was performed on whole cell lysates of fibroblasts from five NLF lines and five FLF lines. NLFs displayed markedly increased levels of PTEN protein in whole-cell lysates than FLFs. To ensure consistent protein loading, the blot was stripped and reprobed with an antibody against β-actin. Relative protein expression was determined as the densitometric ratio of PTEN to β-actin. (C) PTEN phosphatase activity is diminished in FLFs compared with NLFs. Phosphatase activity was assessed in five NLF and five FLF lines. To ensure reproducibility, the experiment was repeated twice. Representative results are shown.

DISCUSSION

UIP/IPF is characterized by disruption of the intact alveolar basement membrane, accumulation of intraalveolar fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, and deposition and accumulation of ECM proteins. Fibroblast/myofibroblasts likely migrate through the disrupted basement membrane to enter the intraalveolar space. Our data demonstrate a role for the α5β1 integrin in fibroblast migration through basement membranes. We further show that PTEN, a tumor suppressor and migration/invasion inhibitor, is activated downstream of the α4β1 integrin and may serve as one mechanism of inhibiting the migratory phenotype of fibroblasts. Although the current experiments assessed the ability of the α4β1 integrin to inhibit fibroblast migration induced by α5β1 integrin ligation, it remains a distinct possibility that other migratory stimuli might also be negatively regulated through this pathway.

It has been suggested that UIP/IPF represents a condition of “overexuberant” wound healing (28). Furthermore, mounting evidence suggests that an abnormal host response to an unknown (and possibly ongoing) injurious agent/event may be responsible for the progressive fibrosis associated with UIP/IPF (29). Our current results reveal a phenotypic difference between FLFs and NLFs that may account for the increased migration of fibroblasts into the alveolus in UIP/IPF. The migratory phenotype of FLFs is consistent with the findings of Suganuma and colleagues who also demonstrated increased in vitro motility of FLFs compared with NLFs (30). However, unlike the findings of Suganuma and colleagues, who demonstrated increased chemotaxis toward a known chemoattractant (platelet-derived growth factor) (30), our data demonstrate that fibronectin fragments binding the α5β1 integrin induce migration away from the stimulus. Thus, our data suggest that fibronectin fragments in the provisional wound-healing matrix may promote the migration of fibroblasts into the alveolar space.

In this study, we also evaluated the role of another fibronectin-binding integrin, α4β1, in regulating fibroblast migration. Other matrix receptors, which have not been addressed in this article, may be instrumental in inducing cellular migration, such as α2β1 integrin and CD44 (31, 32). Whether the α4β1 integrin and PTEN are capable of regulating the migratory responses due to other stimuli remains to be determined. Clearly, PTEN is able to attenuate spontaneous cellular migration. It remains possible that migratory regulation by the α4β1 integrin and PTEN is independent of the stimulus and rather represents a global mechanism for regulating cellular migration.

In this article, our data show that the α4β1 integrin activation inhibits migration of lung fibroblasts induced by α5β1 integrin ligation. This finding is in contrast to other investigators, who have shown that ligation of the α4β1 integrin reduces cell spreading and induces cell migration (33, 34). It should be noted, however, that in these studies the α4β1 integrin was ligated in isolation, whereas we examined the effect of combined ligation of α4β1 and α5β1 integrin using specific fibronectin fragments or with intact fibronectin. This difference further highlights the complexity of the interactions between integrin receptors that regulate cellular phenotypes, including that related to migration/invasion.

We found that simultaneous ligation of both α4β1 and α5β1 integrins inhibits migration of NLFs across a Matrigel basement membrane. Although our data suggest that ligation of the α4β1 integrin retards cell migration, we cannot discount the possibility that diminished responses were due to enhanced apoptosis of NLFs. In support of this hypothesis, Hadden and Henke have shown that lung fibroblasts from patients with acute lung injury undergo apoptosis after 72 hours in the presence of fibronectin fragments, including the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide (found in the central cell-binding domain of fibronectin) and the CS-1 fragment (35). Indeed, our data show that in the presence of the α4β1-binding fibronectin fragments, activity of PTEN is increased in NLFs; the latter effect has been linked to cellular apoptosis (36). Many authors have postulated decreased apoptosis of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci of UIP as one mechanism of fibroblast accumulation and ongoing fibrosis (29, 35, 37), although Ramos and colleagues showed increased spontaneous rates of apoptosis in vitro in lung fibroblasts/myofibroblasts isolated from patients with IPF (38). It is interesting to speculate that diminished PTEN expression in fibroblasts and/or myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci would promote an antiapoptotic, prosurvival phenotype. Clearly, this concept needs to be explored further.

Although PTEN was first described as a dual-activity phosphatase deleted in numerous malignancies (19), a number of investigators have shown decreased PTEN expression in nonmalignant disease states. For example, PTEN expression was shown to be diminished in invasive synovial fibroblasts from patients with rheumatoid arthritis (20). More recently, Kwak and colleagues demonstrated decreased PTEN expression in airway epithelial cells in a murine asthma model (39). Importantly, these investigators demonstrated that repletion of PTEN in airway epithelial cells of these ovalbumin-challenged mice resulted in decreased eosinophil influx, decreased elaboration of eosinophil products, and diminished airway hyperreactivity (39). Interestingly, we found PTEN gene and protein expression, as well as phosphatase activity, is constitutively decreased in FLFs. Additionally, in response to the CS-1 peptide, PTEN activity decreases further in FLFs, which may account for the continued migratory phenotype observed in these cells. We postulate that PTEN may play a critical role in the accumulation of fibroblasts in lungs of patients with UIP; thus, identification of mechanisms that induce PTEN expression and activity might be of therapeutic benefit in UIP/IPF and other fibroproliferative diseases to decrease fibroblast accumulation in airspaces.

In summary, our data illustrate a phenotypic difference between NLFs and FLFs that may contribute to the inexorable progression of lung fibrosis associated with UIP/IPF. We show that the migratory/invasive phenotype in lung fibroblasts can be induced through α5β1 integrin and negatively regulated by α4β1 integrin signaling. Importantly, we demonstrate a deficiency of PTEN expression and activity in FLFs. Together, these data define a new phenotypic characteristic of lung fibroblasts from patients with UIP/IPF and implicate decreased PTEN function as a novel, potential “profibrotic” mechanism in progressive pulmonary fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Thomas Moore, Ph.D., and Dennis Lindell for their expert help with flow cytometry, as well as to Jeffrey Curtis, M.D., and Marc Peters-Golden, M.D., for their advice and critical reading of the article. We thank Dr. Maria-Magdalena Georgescu (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) for technical assistance with the PTEN phosphatase activity assay.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL70990, the American Lung Association-Dalsemer Award DA-004-N, and a Young Investigator Grant from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (E.S.W.) and National Institutes of Health grant CA94121 (D.A.A.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: E.S.W. has no declared conflict of interest; V.J.T. has no declared conflict of interest; S.L.C. has no declared conflict of interest; E.G.D. has no declared conflict of interest; D.L.L. has no declared conflict of interest; S.M. has no declared conflict of interest; G.B.T. has no declared conflict of interest; D.A.A. has no declared conflict of interest.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents online at www.atsjournals.org

References

- 1.Kuhn C, III, Boldt J, King TE, Jr, Crouch E, Vartio T, McDonald JA. An immunohistochemical study of architectural remodeling and connective tissue synthesis in pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1693–1703. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segura A, Yuste A, Cercos A, Lopez-Tendero P, Girones R, Perez-Fidalgo JA, Herranz C. Pulmonary fibrosis induced by cyclophosphamide. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:894–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch JP, III, Hunninghake GW. Pulmonary complications of collagen vascular disease. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:17–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vuyst P, Camus P. The past and present of pneumoconioses. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2000;6:151–156. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International Consensus Statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;161:646–664. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.ats3-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katzenstein AL, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1301–1315. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King T., Jr . Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Schwarz M, King T Jr, editors. Interstitial lung disease. Hamilton, OR: B. C. Decker; 1998. pp. 597–644. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn C, McDonald JA. The roles of the myofibroblast in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical features of sites of active extracellular matrix synthesis. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1257–1265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald JA, Broekelmann TJ, Matheke ML, Crouch E, Koo M, Kuhn C., III A monoclonal antibody to the carboxyterminal domain of procollagen type I visualizes collagen-synthesizing fibroblasts: detection of an altered fibroblast phenotype in lungs of patients with pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1237–1244. doi: 10.1172/JCI112707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rennard SI, Hunninghake GW, Bitterman PB, Crystal RG. Production of fibronectin by the human alveolar macrophage: mechanism for the recruitment of fibroblasts to sites of tissue injury in interstitial lung diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7147–7151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruoslahti E. Fibronectin and its receptors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:375–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson S, Svineng G, Wennerberg K, Armulik A, Lohikangas L. Fibronectin-integrin interactions. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d126–d146. doi: 10.2741/a178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komoriya A, Green LJ, Mervic M, Yamada SS, Yamada KM, Humphries MJ. The minimal essential sequence for a major cell type-specific adhesion site (CS1) within the alternatively spliced type III connecting segment domain of fibronectin is leucine-aspartic acid-valine. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15075–15079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ignatoski KM, Maehama T, Markwart SM, Dixon JE, Livant DL, Ethier SP. ERBB-2 overexpression confers PI 3′ kinase-dependent invasion capacity on human mammary epithelial cells. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:666–674. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livant DL, Brabec RK, Kurachi K, Allen DL, Wu Y, Haaseth R, Andrews P, Ethier SP, Markwart S. The PHSRN sequence induces extracellular matrix invasion and accelerates wound healing in obese diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1537–1545. doi: 10.1172/JCI8527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aota S, Nomizu M, Yamada KM. The short amino acid sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn in human fibronectin enhances cell-adhesive function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24756–24761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pap T, Franz JK, Hummel KM, Jeisy E, Gay R, Gay S. Activation of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: lack of expression of the tumour suppressor PTEN at sites of invasive growth and destruction. Arthritis Res. 1999;1:59–64. doi: 10.1186/ar69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Y, Lin YZ, LaPushin R, Cuevas B, Fang X, Yu SX, Davies MA, Khan H, Furui T, Mao M, et al. The PTEN/MMAC1/TEP tumor suppressor gene decreases cell growth and induces apoptosis and anoikis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:7034–7045. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White ES, Carskadon SL, Livant DL, Markwart S, Toews GB, Arenberg DA. Fibrotic-lung fibroblast invasion of basement membranes is modulated by PTEN. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:A362. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-041OC. abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White ES, Livant DL, Markwart S, Arenberg DA. Monocyte-fibronectin interactions, via alpha(5)beta(1) integrin, induce expression of CXC chemokine-dependent angiogenic activity. J Immunol. 2001;167:5362–5366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livant DL, Linn S, Markwart S, Shuster J. Invasion of selectively permeable sea urchin embryo basement membranes by metastatic tumor cells, but not by their normal counterparts. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5085–5093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura M, Gu J, Takino T, Yamada KM. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and growth: differential involvement of focal adhesion kinase and p130Cas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:442–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georgescu MM, Kirsch KH, Akagi T, Shishido T, Hanafusa H. The tumor-suppressor activity of PTEN is regulated by its carboxyl-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10182–10187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink L, Seeger W, Ermert L, Hanze J, Stahl U, Grimminger F, Kummer W, Bohle RM. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR after laser-assisted cell picking. Nat Med. 1998;4:1329–1333. doi: 10.1038/3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mutsaers SE, Bishop JE, McGrouther G, Laurent GJ. Mechanisms of tissue repair: from wound healing to fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suganuma H, Sato A, Tamura R, Chida K. Enhanced migration of fibroblasts derived from lungs with fibrotic lesions. Thorax. 1995;50:984–989. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.9.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petit V, Boyer B, Thiery JP, Valles AM. Characterization of the signaling pathways regulating alpha2beta1 integrin-mediated events by a pharmacological approach. Cell Adhes Commun. 1999;7:151–165. doi: 10.3109/15419069909010799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svee K, White J, Vaillant P, Jessurun J, Roongta U, Krumwiede M, Johnson D, Henke C. Acute lung injury fibroblast migration and invasion of a fibrin matrix is mediated by CD44. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1713–1727. doi: 10.1172/JCI118970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostafavi-Pour Z, Askari JA, Parkinson SJ, Parker PJ, Ng TTC, Humphries MJ. Integrin-specific signaling pathways controlling focal adhesion formation and cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:155–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Thomas SM, Woodside DG, Rose DM, Kiosses WB, Pfaff M, Ginsberg MH. Binding of paxillin to alpha4 integrins modifies integrin-dependent biological responses. Nature. 1999;402:676–681. doi: 10.1038/45264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hadden HL, Henke CA. Induction of lung fibroblast apoptosis by soluble fibronectin peptides. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1553–1560. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.2001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maehama T, Dixon JE. PTEN: a tumour suppressor that functions as a phospholipid phosphatase. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang HY, Phan SH. Inhibition of myofibroblast apoptosis by transforming growth factor beta(1) Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:658–665. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.6.3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos C, Montano M, Garcia-Alvarez J, Ruiz V, Uhal BD, Selman M, Pardo A. Fibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and normal lungs differ in growth rate, apoptosis, and tissue inhibitor of metallo-proteinases expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:591–598. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.5.4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwak Y-G, Song CH, Yi HK, Hwang PH, Kim J-S, Lee KS, Lee YC. Involvement of PTEN in airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in bronchial asthma. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1083–1092. doi: 10.1172/JCI16440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.