Abstract

Intracellular Toxoplasma gondii grown in human foreskin fibroblast cells transported nitrobenzylthioinosine {NBMPR; 6-[(4-nitrobenzyl)mercapto]-9-β-d-ribofuranosylpurine}, an inhibitor of nucleoside transport in mammalian cells, as well as the nonphysiological β-l-enantiomers of purine nucleosides, β-l-adenosine, β-l-deoxyadenosine, and β-l-guanosine. The β-l-pyrimidine nucleosides, β-l-uridine, β-l-cytidine, and β-l-thymidine, were not transported. The uptake of NBMPR and the nonphysiological purine nucleoside β-l-enantiomers by the intracellular parasites also implies that Toxoplasma-infected cells can transport these nucleosides. In sharp contrast, under the same conditions, uninfected fibroblast cells did not transport NBMPR or any of the unnatural β-l-nucleosides. β-d-Adenosine and dipyridamole, another inhibitor of nucleoside transport, inhibited the uptake of NBMPR and β-l-stereoisomers of the purine nucleosides by intracellular Toxoplasma and Toxoplasma-infected cells. Furthermore, infection with a Toxoplasma mutant deficient in parasite adenosine/purine nucleoside transport reduced or abolished the uptake of β-d-adenosine, NBMPR, and purine β-l-nucleosides. Hence, the presence of the Toxoplasma adenosine/purine nucleoside transporters is apparently essential for the uptake of NBMPR and purine β-l-nucleosides by intracellular Toxoplasma and Toxoplasma-infected cells. These results also demonstrate that, in contrast to the mammalian nucleoside transporters, the Toxoplasma adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) lacks stereospecificity and substrate specificity in the transport of purine nucleosides. In addition, infection with T. gondii confers the properties of the parasite's purine nucleoside transport on the parasitized host cells and enables the infected cells to transport purine nucleosides that were not transported by uninfected cells. These unique characteristics of purine nucleoside transport in T. gondii may aid in the identification of new promising antitoxoplasmic drugs.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasitic protozoan which causes the disease toxoplasmosis. Infection with T. gondii is quite common in humans (as high as 60% of the population in the United States are seropositive) but is asymptomatic (90% of cases) in immunocompetent individuals (19). By contrast, the disease represents a major health problem for immunocompromised individuals, such as AIDS patients and the unborn children of infected mothers (20, 23, 26). Toxoplasmic encephalitis has become the most common cause of intracerebral mass lesions in AIDS patients and possibly the most commonly recognized opportunistic infection of the central nervous system (20, 23). The frequency of congenital toxoplasmosis is as high as 1/1,000 live births (23). Effects range in severity from asymptomatic to stillbirth, with the most common ailments being retinochoroiditis, cerebral calcifications, psychomotor or mental retardation, and severe brain damage (23).

In spite of the tragic consequences of toxoplasmosis, the therapy for the disease has not changed in the last 25 years. The efficacy of the current therapy for toxoplasmosis (a combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine) is limited, primarily by serious host toxicity and ineffectiveness against tissue cysts (20, 23, 26, 29). Furthermore, as many as 50% of patients do not respond to therapy (20). Other therapies, e.g., clindamycin or atovaquone, have met with limited success particularly in the long-term management of these patients. Therefore, it is imperative to search for more-efficacious and less-toxic therapies for the treatment and long-term management of toxoplasmosis.

The rational design of a drug depends on the exploitation of fundamental biochemical or metabolic differences between pathogens and their host. Structure-activity relationship studies of T. gondii adenosine kinase (EC 2.7.1.20) demonstrated significant differences between the enzymes from Toxoplasma and those from their mammalian hosts in their substrate specificities (16). Various 6-substituted 9-β-d-ribofuranosylpurines were found to be among the best ligands that bind to T. gondii adenosine kinase (16). This was quite unusual since the compounds were not known to be active ligands of adenosine kinase from other species. Among these 6-substituted 9-β-d-ribofuranosylpurines, nitrobenzylthioinosine {NBMPR; 6-[(4-nitrobenzyl)mercapto]-9-β-d-ribofuranosylpurine} was shown to be phosphorylated to the nucleotide level by the T. gondii, but not the mammalian, adenosine kinase and exerted selective toxicity against T. gondii-infected cells (12, 13).

NBMPR has been extensively investigated as an inhibitor of nucleoside transport in mammalian cells. However, none of these studies has shown that NBMPR is transported into or metabolized by mammalian cells. Furthermore, there is no direct evidence that T. gondii can transport NBMPR (4, 12, 13). How NBMPR enters Toxoplasma-infected cells and subsequently the intracellular parasites is not known.

Transport studies on extracellular Toxoplasma identified two carriers that can transport purine nucleosides (4, 5, 25). The first is a nonspecific nucleoside transporter (TgAT2) that seems to transport both purine and pyrimidine nucleosides (5). The second is an adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter (TgAT1), with β-d-adenosine being the preferred substrate (4). However, it is not known whether either of these two nucleoside carriers can transport NBMPR.

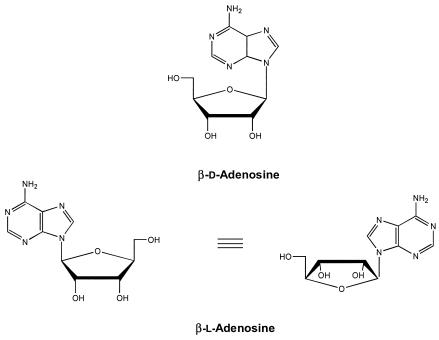

In the present study, we established that NBMPR is a permeant for the adenosine/purine nucleoside carrier(s) in T. gondii. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the Toxoplasma adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) is different from mammalian equilibratory and concentrative transporters in that it is not stereospecifc. In contrast to mammalian cells, the parasite adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) transports nonphysiological β-l-enantiomers of purine nucleosides (β-l-adenosine, β-l-deoxyadenosine, and β-l-guanosine). Figure 1 shows the chemical structures of β-d- and β-l-adenosine.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of the β-d- and β-l-enantiomers of adenosine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and supplies.

β-d-[2,8-3H]adenosine (26.8 Ci/mmol), β-l-[2,8-3H]adenosine (44 Ci/mmol), β-l-[3H]guanosine (0.5 Ci/mmol), β-l-[2,8-3H]deoxyadenosine (32 Ci/mmol), β-d-[G-3H]NBMPR (20.5 Ci/mmol), β-d-[8-14C]inosine (53 mCi/mmol), β-l-[methyl-3H]thymidine (21.9 Ci/mmol), β-l-[3H]uridine (23.7 Ci/mmol), and β-l-[3H]cytidine (15.2 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, Calif. Unlabeled β-l-adenosine, β-l-deoxyadenosine, β-l-guanosine, β-l-uridine, β-l-cytidine, and β-l-thymidine, were generously provided by ldenix Pharmaceuticals, Boston, Mass. Preformulated tetrabutyl ammonium phosphate buffer was purchased from Alltech Association, Inc., Deerfield, Ill. All other chemicals and compounds were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo., or Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Maintenance of T. gondii.

The RH and TgAT− strains of T. gondii were propagated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) passage in female CD 1 mice (20 to 25 g). RH is a wild type strain and the TgAT− strain is a mutant deficient in the adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) (4, 27). Mice were injected i.p. with an inoculum (106 cells) of T. gondii contained in 0.2 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, and were sacrificed after 2 to 3 days by inhalation of ether. The parasites were harvested from the peritoneal cavity by injection, aspiration, and reinjection of 3 to 5 ml of PBS (two or three times). The peritoneal fluid was examined microscopically to determine the concentration of T. gondii and to ascertain the extent of contamination by host cells. Two-day transfers generally produce parasite preparations that contain very little contamination and have a viability of >95%.

Preparation of parasites.

When T. gondii was used for in vitro incorporation studies, the procedure was performed aseptically and the parasites were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO BRL) containing 100 U of penicillin G/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin sulfate/ml, and 3% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah).

Uptake of radiolabeled compounds in the presence and absence of other compounds.

Uptake and incorporation of the radiolabeled compounds into the nucleoside and nucleotide pool of intracellular T. gondii were carried out in at least triplicate by using monolayers of human foreskin fibroblasts cultured for no more than 30 passages in RPMI 1640 and infected with T. gondii. Briefly, confluent cells (4 to 5 days of incubation) were cultured for 24 h in 24-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (∼5 × 105 cells/ml/well) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2-95% air to allow the cells to attach. The medium was then removed, and the cells were infected with isolated T. gondii in medium with 3% FBS (one parasite per cell). After 1 h of incubation, the cultures were washed with 10% FBS medium to remove the extracellular parasites. FBS was maintained at a final concentration of 10%. The radiolabeled purine nucleosides were then added to cultures of the parasite-infected cells to give a final concentration of 10 μM, in the presence and absence of competing nucleosides or nucleoside transport inhibitors at a final concentration of 100 μM. After 4 h of incubation the fibroblasts were released from the wells by aspirating the medium; the cells were then washed three times with cold PBS and trypsinized by the addition of 200 μl of trypsin-EDTA (2.5×) to each well. One milliliter of 60% ice-cold methanol was added to each well, after which the cells were forced to break up by passing them through a 22-gauge needle. Each well's contents were then transferred into an Eppendorf tube, and the samples were stored at −20°C overnight. The samples were then spun down at 1,200 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was aspirated, air dried, and then reconstituted in 210 μl of double-distilled water. The radioactivity in samples of 10 μl was counted in scintillation vials containing 5 ml of Econo-Safe scintillation fluor (Research Products International Corp., Mount Prospect, Ill.) with an LS5801 (Beckman) scintillation counter. The remaining 200 μl was stored at −20°C until analysis by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC).

HPLC analysis.

The HPLC analysis of the nucleoside and nucleotide pool of the intracellular Toxoplasma was performed on two Hypersil C18 reverse-phase (25- by 0.4-cm; octyldecyl saline, 5 μm) columns (Jones Chromatography, Littleton, Colo.) tandemly connected to a computer-controlled Hewlett-Packard 1050 HPLC system with an autosampler, quaternary pump, and multiple-wavelength diode array base triple-channel UV monitor. A 100-μl aliquot of the extract was injected. Elution was performed stepwise by using two mobile phases, 25 mM ammonium acetate in 5 mM preformulated tetrabutyl ammonium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (buffer A), and methanol (buffer B), and a multistage linear gradient. Elution started with buffer B at a gradient of 0 to 10% during the first 5 min and a constant flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The elution flow was then increased to 1 ml/min, and the gradient of buffer B was increased from 10 to 15% at 40 min; it reached 25% at 45 min and 30% at 55 min and was maintained at 30% until 60 min. The radioactivity content of the eluent was quantitated by the use of an online 525TR Radiomatic Flo-One radiochromatography analyzer (Packard Instrument Company, Inc., Meriden, Conn.). Under these chromatographic conditions, the retention times of β-d-adenosine, β-l-adenosine, β-l-deoxyadenosine, AMP, ADP, ATP, NBMPR, and NBMPR 5′-monophosphate were about 25, 20, 30, 42, 47, 50, 68, and 56 min, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

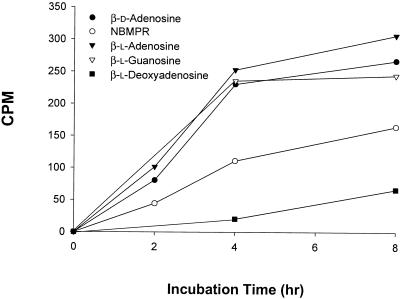

Figure 2 shows that intracellular Toxoplasma parasites grown in human fibroblasts in culture were able to take up β-d-adenosine and NBMPR, as well as the nonphysiological purine nucleoside β-l-enantiomers, β-l-adenosine, β-l-deoxyadenosine, and β-l-guanosine; β-l-deoxyadenosine was the poorest substrate. Although the uptake of nonphysiological purine nucleoside enantiomers increased with time, HPLC analysis of the radioactive contents of parasites freed from infected cells indicated that, under these experimental conditions, none of the l-enantiomers were metabolized to their respective nucleotides by the intracellular parasites. On the other hand, β-d-adenosine and NBMPR were metabolized to their respective nucleoside 5′-monophosphates. The uptake of NBMPR and the nonphysiological purine nucleoside β-l-enantiomers by the intracellular parasites also implies that Toxoplasma-infected cells can transport these nucleosides. In sharp contrast, under the same conditions, uninfected fibroblast cells did not transport NBMPR or any of the unnatural β-l-nucleosides. The pyrimidine enantiomers, β-l-uridine, β-l-cytidine, and β-l-thymidine, were poorly transported by parasite-infected or noninfected cells if at all (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Uptake of β-d-adenosine, NBMPR, and β-l-enantiomers of purine nucleosides by intracellular T. gondii grown in human fibroblast cells in culture. Infected cells were incubated with the substrate (10 μM) for different time periods. Each value is the mean from two experiments with three replicates each.

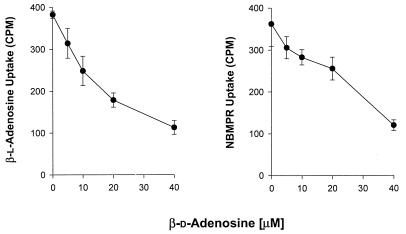

Competition studies were performed in an effort to determine whether NBMPR and the unnatural purine β-l-enantiomers are transported into intracellular Toxoplasma and Toxoplasma-infected cells by the same nucleoside carrier(s) that transports β-d-adenosine. Figure 3 shows that the uptake of NBMPR and β-l-adenosine was inhibited by β-d-adenosine in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that NBMPR and β-l-adenosine in intracellular Toxoplasma and Toxoplasma-infected cells are transported by the same carrier(s) that transports β-d-adenosine.

FIG. 3.

Effects of different concentrations of β-d-adenosine on the uptake of NBMPR and β-l-adenosine in intracellular T. gondii grown in human fibroblast cells in culture. Infected cells were incubated with the substrate (10 μM) for 4 h in the presence of different concentrations of β-d-adenosine. Each value is the mean from two experiments with three replicates each.

The results in Table 1 further confirm that NBMPR, the purine β-l-enantiomers, and β-d-adenosine are transported by the same carrier(s). The uptake of β-d-adenosine was substantially inhibited by β-l-adenosine (46%), and the uptake of β-l-adenosine was inhibited by β-d-adenosine to the same extent. The uptake of β-d-adenosine and that of β-l-adenosine were also inhibited by β-l-deoxyadenosine (41 and 20%, respectively) and β-l-guanosine (57 and 43%, respectively). Likewise, NBMPR uptake was significantly affected by β-d-adenosine (67%), β-l-adenosine (53%), β-l-deoxyadenosine (20%), and β-l-guanosine (43%). In a like manner, NBMPR inhibited the uptake of β-d-adenosine (67%), β-l-adenosine (63%), β-l-deoxyadenosine (33%), and β-l-guanosine (46%).

TABLE 1.

Effect of different compounds on the uptake of various purine β-d- and β-l-nucleoside enantiomers by intracellular T. gondii grown in human fibroblast cells in culturea

| Compound | % Inhibition

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-d-Adenosine | β-l-Adenosine | β-l-Deoxyadenosine | β-l-Guanosine | β-d-Inosine | Hypoxanthine | NBMPR | Dipyridamole | |

| β-d-Adenosine | NDb | 46 | 41 | 57 | 2 | 10 | 67 | 63 |

| β-l-Adenosine | 46 | ND | 20 | 43 | 19 | 7 | 63 | 70 |

| β-l-Deoxyadenosine | 46 | 34 | ND | 16 | 12 | 14 | 33 | 31 |

| β-l-Guanosine | 50 | 49 | 26 | ND | 12 | 24 | 46 | 34 |

| β-d-Inosine | 18 | 26 | 1 | 27 | ND | 13 | 15 | 11 |

| NBMPR | 67 | 53 | 20 | 43 | 19 | 18 | ND | 46 |

T. gondii-infected fibroblast cells were incubated with the substrate (10 μM) for 4 h in the presence or absence of the inhibitor (100 μM). Each value is the mean from two experiments with three replicates each.

ND, not determined.

By comparison, β-d-inosine and hypoxanthine were less effective in inhibiting the uptake of all nucleosides tested, and β-d-inosine uptake was not considerably affected by these nucleosides. Similar results were observed in free extracellular tachyzoites (25). Transport of β-d-adenosine was somewhat inhibited by β-d-inosine. However, the transport of β-d-inosine was less affected by β-d-adenosine (25).

Dipyridamole, an inhibitor of adenosine transport in Toxoplasma (4, 25) and mammalian cells (reference 13 and references therein) inhibited the uptake of β-d-adenosine (63%), β-l-adenosine (70%), β-l-deoxyadenosine (31%), β-l-guanosine (34%), and NBMPR (46%). In contrast, the effect of dipyridamole on the uptake of β-d-inosine (11%) was less pronounced. Similar results for extracellular parasites were observed (25).

Previous studies (4, 5, 25) identified two purine nucleoside transporters in free extracellular T. gondii tachyzoites. The first, TgAT2, is a nonspecific nucleoside transporter that seems to transport both purine and pyrimidine nucleosides (5). The second, TgAT1, is an adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter; adenosine is the preferred substrate, but TgAT1 can also transport β-d-inosine (4). Genetic evidence indicates that TgAT1 is the sole relevant transporter of adenosine in T. gondii. Inactivation of the TgAT1 locus eliminates virtually all adenosine transport (4).

The strong correspondence between the results from previous studies on extracellular free parasites (4, 25) and the present results on intracellular parasites suggests that purine nucleoside transport in intracellular parasites is essentially the same as that in free extracellular parasites. Therefore, it was proposed that both TgAT1 and TgAT2 are products of the same gene (5).

To ascertain further that the transport of NBMPR and purine β-l-nucleosides into intracellular Toxoplasma and Toxoplasma-infected cells is mediated by the parasite adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s), the uptake of NBMPR and purine β-l-nucleosides was studied in fibroblast cells infected with TgAT−, a Toxoplasma mutant which is deficient in adenosine/purine nucleoside transport (4). Infection with the TgAT− Toxoplasma mutant reduced or abolished the uptake of NBMPR and purine β-l-nucleosides (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to infection with wild-type parasites (Fig. 2), infection with the TgAT− Toxoplasma transport mutant did not change the characteristics of nucleoside transport in the host cells to enable the infected host cells to take up NBMPR and the purine β-l-nucleosides. These results demonstrate that the observed uptake of NBMPR and purine β-l-nucleosides by intracellular Toxoplasma and host cells infected with wild-type parasites (Fig. 2) is indeed mediated by the same adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) that transports the natural β-d-adenosine into extracellular parasites. Therefore, it appears that infection with T. gondii conferred the properties of the parasite's purine nucleoside transport on the parasitized cells and enabled these infected cells to transport purine nucleosides (e.g., NBMPR and β-l-nucleosides) that were not transported before infection. Similar results were reported for nucleoside transport in Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes (15, 28) and Plasmodium yoelii-infected mouse erythrocytes (14). Infection with malaria parasites induced the malaria nonstereospecific nucleoside transporter in the parasitized host cells (3).

There is an ongoing debate on how parasitism confers the properties of parasite nucleoside transport on parasitized cells. There are at least four possible pathways for induced nucleoside transport to occur in the parasitized host cell. The first is via an equilibratory high-affinity adenosine transport system (15, 28). The second is by way of a concentrative ion-dependent channel (17). The third pathway proposed is through tubovesicular membranes, which are interconnected networks extending from the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane, where the parasites reside, to the periphery of the infected cell (18). The fourth is a via a duct for the transport of macromolecules that bypasses the host cell membrane (22). Recent studies on the characteristics of P. falciparum nucleoside transporter PfNT1 (3) ruled out all proposed pathways except the induction of an equilibratory high-affinity adenosine transport system. The present results strongly suggest that a similar situation may exist in T. gondii-infected cells. The change in the substrate specificity and stereospecificity of nucleoside transport in host cells resulting from infection with Toxoplasma is most likely due to the induction of the Toxoplasma nonstereospecific adenosine transporter(s), thereby conferring its properties on the nucleoside transport of the parasitized host cells. In agreement with this conclusion, previous studies on Toxoplasma-infected cells excluded the possibility that plasma membrane proteins of host cells might form membrane channels or transporters from the parasitophorous vacuole membrane that surrounds the parasites within the host cells (references 2 and 24 and references therein).

The previous (4, 12, 13, 25) and present results demonstrate that the adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) in T. gondii, differs from the mammalian equilibratory and concentrative transporters in three notable characteristics. First, the parasite adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) exhibits lack of stereospecificity, transporting both β-d-adenosine and β-l-adenosine as well as other β-l-enantiomers of purine nucleosides. Mammalian transporters, on the other hand, are stereospecific for the d-enantiomers. Second, unlike mammalian transporters, the Toxoplasma adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) is not inhibited by NBMPR but rather by high concentrations of dipyridamole. Third, NBMPR appears to be a permeant for this carrier(s), as Toxoplasma transports and metabolizes NBMPR. In addition infection with T. gondii parasites induces the Toxoplasma adenosine/purine nucleoside transporter(s) in the parasitized host cells.

In conclusion, further studies on nucleoside transporters in Toxoplasma are likely to provide insight into the mechanisms of purine transport and salvage by T. gondii and facilitate the assessment of purine transporters as valid chemotherapeutic targets for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. An understanding of the mechanisms of transport and membrane function in parasites as well as the differences in their properties compared to those of their mammalian hosts may provide the foundation for rational antiparasite drug development. Indeed, differences in the properties of nucleoside transport between mammalian and parasitic cells were the basis of a combination therapy approach involving the use of a cytotoxic purine nucleoside analogue and host-protecting mammalian transport inhibitors (1, 6-11, 14, 15, 21).

Acknowledgments

We thank Idenix Pharmaceuticals for generously providing the β-l-nucleosides.

This investigation was supported by grants AI-29950 and AI-42975, awarded by the NIAID, DHHS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baer, H. P., A. El-Soofi, and A. Selim. 1988. Treatment of Schistosoma mansoni- and Schistosoma haematobium-infected mice with a combination of tubercidin and nucleoside transport inhibitor. Med. Sci. Res. 16:919. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudes, D., K. R. Peck, M. A. Afifi, C. J. M. Beckers, and K. A. Joiner. 1994. Tandemly repeated genes encode nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase isoforms secreted into parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29252-29260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter, N. S., C. Ben Mamoun, W. Liu, E. O. Silva, S. M. Landfear, D. E. Goldberg, and B. Ullman. 2000. Isolation and functional characterization of the PfNT1 nucleoside transporter gene from Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10683-10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang, C.-W., N. Carter, W. J. Sullivan Jr., R. G. K. Donald, D. S. Roos, F. N. M. Naguib, M. H. el Kouni, B. Ullman, and C. M. Wilson. 1999. The adenosine transporter of Toxoplasma gondii. Identification by insertional mutagenesis, cloning, and recombinant expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35255-35261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Koning, H. P., M. I. Al-Salabi, A. M. Cohen, G. H. Coombs, and J. M Wastling. 2003. Identification and characterization of high affinity nucleoside and nucleobase transporters in Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 33:821-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.el Kouni, M. H., D. Diop, and S. Cha. 1983. Combination therapy of schistosomiasis by tubercidin and nitrobenzylthioinosine 5′-monophosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:6667-6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.el Kouni, M. H., P. M. Knopf, and S. Cha. 1985. Combination therapy of Schistosoma japonicum by tubercidin and nitrobenzylthioinosine 5′-monophosphate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 34:3921-3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.el Kouni, M. H., and S. Cha. 1987. Metabolism of adenosine analogues by Schistosoma mansoni and the effect of nucleoside transport inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36:1099-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.el Kouni, M. H., N. J. Messier, and S. Cha. 1987. Treatment of schistosomiasis by purine nucleoside analogues in combination with nucleoside transport inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36:3815-3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el Kouni, M. H., D. Diop, P. O'Shea, R. Carlisle, and J.-P. Sommadossi. 1989. Prevention of tubercidin host toxicity by nitrobenzylthioinosine 5′-monophosphate for the treatment of schistosomiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:824-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.el Kouni, M. H. 1991. Efficacy of combination therapy with tubercidin and nitrobenzylthioinosine 5′-monophosphate against chronic and advanced stages of schistosomiasis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 41:815-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.el Kouni, M. H., V. Guarcello, O. N. Al Safarjalani, and F. N. M. Naguib. 1999. Metabolism and selective toxicity of 6-nitrobenzylthioinosine in Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2437-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.el Kouni, M. H. 2003. Potential chemotherapeutic targets in the purine metabolism of parasites. Pharmacol. Ther., 99:283-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gati, W. P., A. F. W. Stoyke, A. M. Gero, and A. R. P. Paterson. 1987. Nucleoside permeation in mouse erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium yoelii. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 145:1134-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gero, A. M., E. M. A. Bugledich, A. R. P. Paterson, and G. P. Jamieson. 1988. Stage-specific alteration of nucleoside membrane permeability and nitrobenzylthioinosine insensitivity in Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 27:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iltzsch, M. H., S. S. Uber, K. O. Tankersly, and M. H. el Kouni. 1995. Structure-activity relationship of the binding of nucleoside ligands to adenosine kinase from Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem. Pharmacol. 49:1501-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirk, K., H. A. Horner, B. C. Elford, J. C. Ellory, and C. I. Newbold. 1994. Transport of diverse substrates into malaria-infected erythrocytes via a pathway showing functional characteristics of a chloride channel. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3339-3347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauer, S. A., P. K. Rathod, N. Ghori, and K. Haldar. 1997. A membrane network for nutrient import in red cells infected with malaria parasite. Science 276:1122-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luft, B. J. 1989. Toxoplasma gondii, p. 179-279. In P. D. Walzer and R. M. Genta (ed.), Parasitic infections in the compromised host. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 20.Luft, B. J., and J. S. Remington. 1992. AIDS commentary: toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogbunude, P. O. J., and C. O. Ikediobi. 1982. Effects of nitrobenzylthioinosinate on the toxicity of tubercidin and ethidium against Trypanosoma gambiense. Acta Trop. 39:219-224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pouvelle, B., R. Spiegel, L. Hsiao, R. J. Howard, R. L. Morris, A. P. Thomas, and T. F. Taraschi. 1991. Direct access to serum macromolecules by intraerythrocytic malaria parasites. Nature 353:73-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Remington, J. S., R. Mcleod, and G. Desmonts. 1995. Toxoplasmosis, p. 140-267. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders & Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 24.Schwab, J. C., C. J. M. Beckers, and K. A. Joiner. 1994. The parasitophorous vacuole membrane surrounding intracellular Toxoplasma gondii as a membrane sieve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:509-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwab, J. C., M. A. Afifi, G. Pizzarno, R. E. Hanschumacher, and K. A. Joiner. 1995. Toxoplasam gondii tachyzoites possess an unusual plasma membrane adenosine transporter. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 70:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subauste, C. S., and J. S. Remington. 1993. Immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 5:532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan, W. J., Jr., C. W. Chiang, C. M. Wilson, F. N. M. Naguib, M. H. el Kouni, R. G. K. Donald, and D. S. Roos. 1999. Insertional tagging of at least two loci associated with resistance to adenine arabinoside in Toxoplasma gondii, and cloning of the adenosine kinase locus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 103:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upston, J. M., and A. M. Gero. 1995. Parasite induced permeation of nucleosides in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1236:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong, S., and J. S. Remington. 1993. Biology of Toxoplasma gondii. AIDS 7:299-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]