Abstract

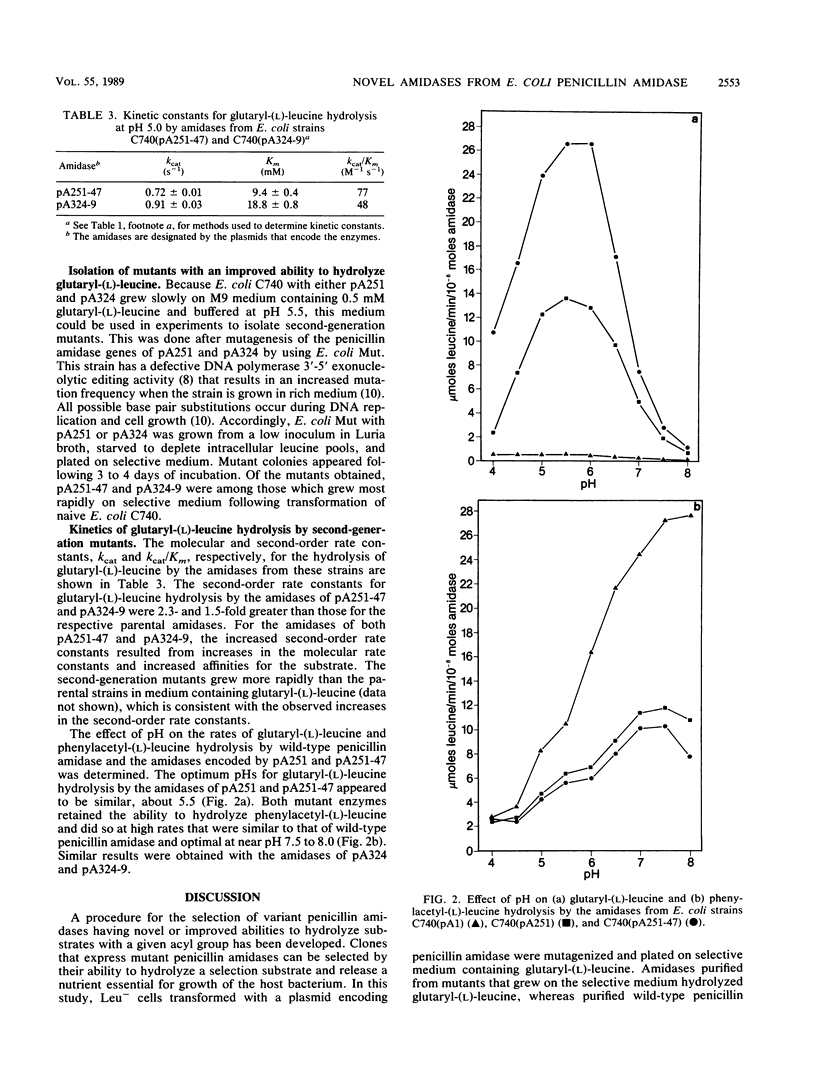

To obtain amidases with novel substrate specificity, the cloned gene for penicillin amidase of Escherichia coli ATCC 11105 was mutagenized and mutants were selected for the ability to hydrolyze glutaryl-(L)-leucine and provide leucine to Leu- host cells. Cells with the wild-type enzyme did not grow in minimal medium containing glutaryl-(L)-leucine as a sole source of leucine. The growth rates of Leu- cells that expressed these mutant amidases increased as the glutaryl-(L)-leucine concentration increased or as the medium pH decreased. Growth of the mutant strains was restricted by modulation of medium pH and glutaryl-(L)-leucine concentration, and successive generations of mutants that more efficiently hydrolyzed glutaryl-(L)-leucine were isolated. The kinetics of glutaryl-(L)-leucine hydrolysis by purified amidases from two mutants and the respective parental strains were determined. Glutaryl-(L)-leucine hydrolysis by the purified mutant amidases occurred most rapidly between pH 5 and 6, whereas hydrolysis by wild-type penicillin amidase at this pH was negligible. The second-order rate constants for glutaryl-(L)-leucine hydrolysis by two "second-generation" mutant amidases, 48 and 77 M-1 s-1, were higher than the rates of hydrolysis by the respective parental amidases. The increased rates of glutaryl-(L)-leucine hydrolysis resulted from both increases in the molecular rate constants and decreases in apparent Km values. The results show that it is possible to deliberately modify the substrate specificity of penicillin amidase and successively select mutants with amidases that are progressively more efficient at hydrolyzing glutaryl-(L)-leucine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Betz J. L., Brown P. R., Smyth M. J., Clarke P. H. Evolution in action. Nature. 1974 Feb 1;247(5439):261–264. doi: 10.1038/247261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns W., Hoppe J., Tsai H., Brüning H. J., Maywald F., Collins J., Mayer H. Structure of the penicillin acylase gene from Escherichia coli: a periplasmic enzyme that undergoes multiple proteolytic processing. J Mol Appl Genet. 1985;3(1):36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. H., Lengyel J. A., Langridge J. Evolution of a second gene for beta-galactosidase in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Jun;70(6):1841–1845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.6.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. C., Cohen S. N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978 Jun;134(3):1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. Deacylation of acylamino compounds other than penicillins by the cell-bound penicillin acylase of Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1969 Dec;115(4):741–745. doi: 10.1042/bj1150741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. Hydrolysis of penicillins and related compounds by the cell-bound penicillin acylase of Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1969 Dec;115(4):733–739. doi: 10.1042/bj1150733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumy G. O., Danley D., McColl A. S., Apostolakos D., Vinick F. J. Experimental evolution of penicillin G acylases from Escherichia coli and Proteus rettgeri. J Bacteriol. 1985 Sep;163(3):925–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.925-932.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols H., Lu C., Burgers P. M. Mutator strains of Escherichia coli, mutD and dnaQ, with defective exonucleolytic editing by DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Apr;80(8):2189–2192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierke C. A., Johnson K. A., Benkovic S. J. Construction and evaluation of the kinetic scheme associated with dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1987 Jun 30;26(13):4085–4092. doi: 10.1021/bi00387a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler R. G., Degnen G. E., Cox E. C. Mutational specificity of a conditional Escherichia coli mutator, mutD5. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;133(3):179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00267667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A., Knowles J. R. Directed selective pressure on a beta-lactamase to analyse molecular changes involved in development of enzyme function. Nature. 1976 Dec 23;264(5588):803–804. doi: 10.1038/264803a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983 Jun 5;166(4):557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrikson R. L., Meredith S. C. Amino acid analysis by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography: precolumn derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate. Anal Biochem. 1984 Jan;136(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles J. R. Tinkering with enzymes: what are we learning? Science. 1987 Jun 5;236(4806):1252–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.3296192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutzbach C., Rauenbusch E. Preparation and general properties of crystalline penicillin acylase from Escherichia coli ATCC 11 105. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1974 Jan;355(1):45–53. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1974.355.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan P. B. Penicillin acylases. An update. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1984 Oct-Dec;9(5-6):537–554. doi: 10.1007/BF02798404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin A. L., Svedas V. K., Berezin I. V. Substrate specificity of penicillin amidase from E. coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980 Dec 4;616(2):283–289. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(80)90145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortlock R. P. Metabolic acquisitions through laboratory selection. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1982;36:259–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaskie A., Roets E., Vanderhaeghe H. Substrate specificity of penicillin acylase of E. coli. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1978 Aug;31(8):783–788. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.31.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher G., Sizmann D., Haug H., Buckel P., Böck A. Penicillin acylase from E. coli: unique gene-protein relation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Jul 25;14(14):5713–5727. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.14.5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewiński M., Kuropatwa M., Szewczuk A. Phenylalkylsulfonyl derivatives as covalent inhibitors of penicillin amidase. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1984 Aug;365(8):829–837. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1984.365.2.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills C. Controlling protein evolution. Fed Proc. 1976 Aug;35(10):2098–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]