Abstract

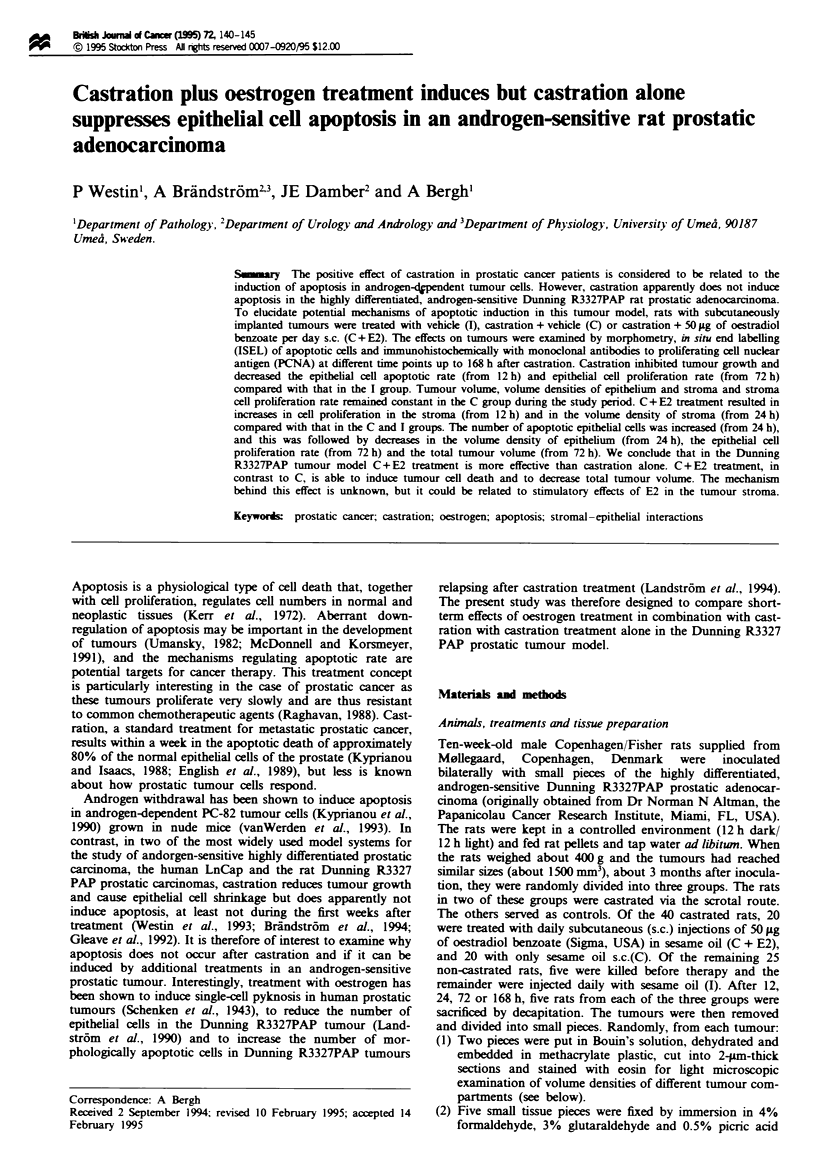

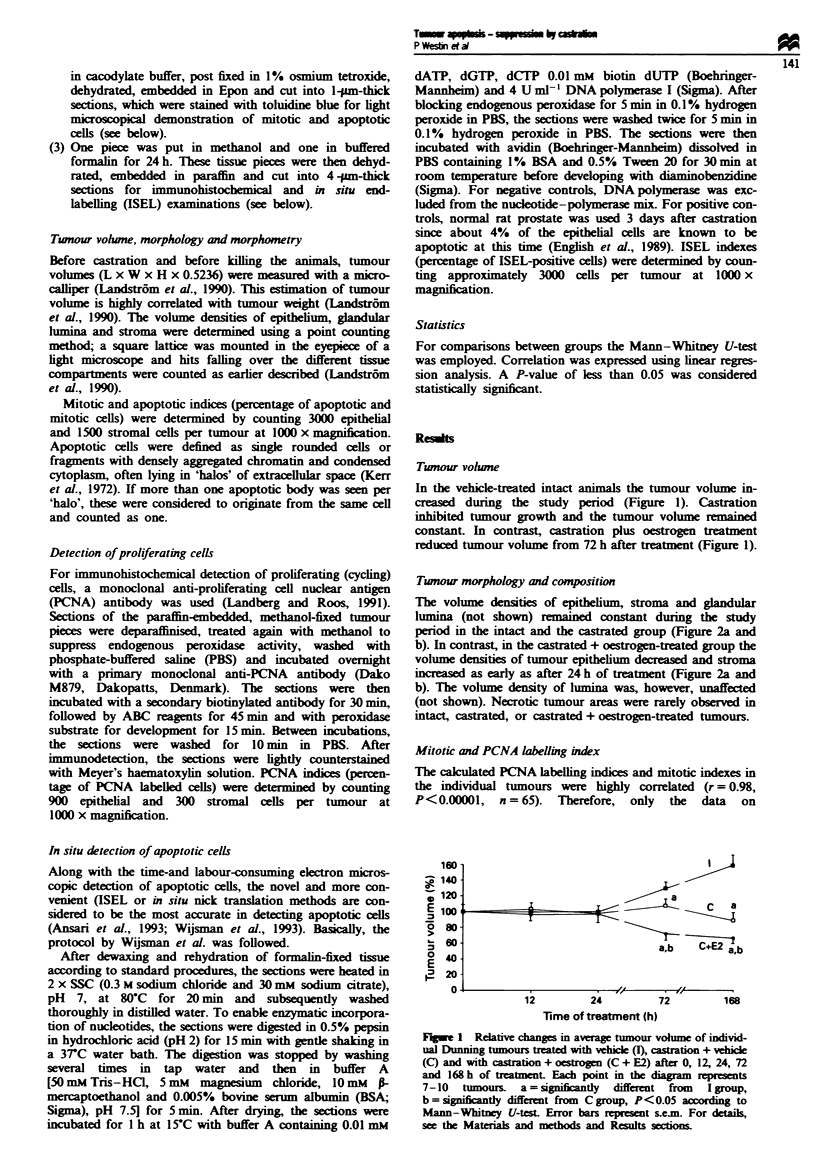

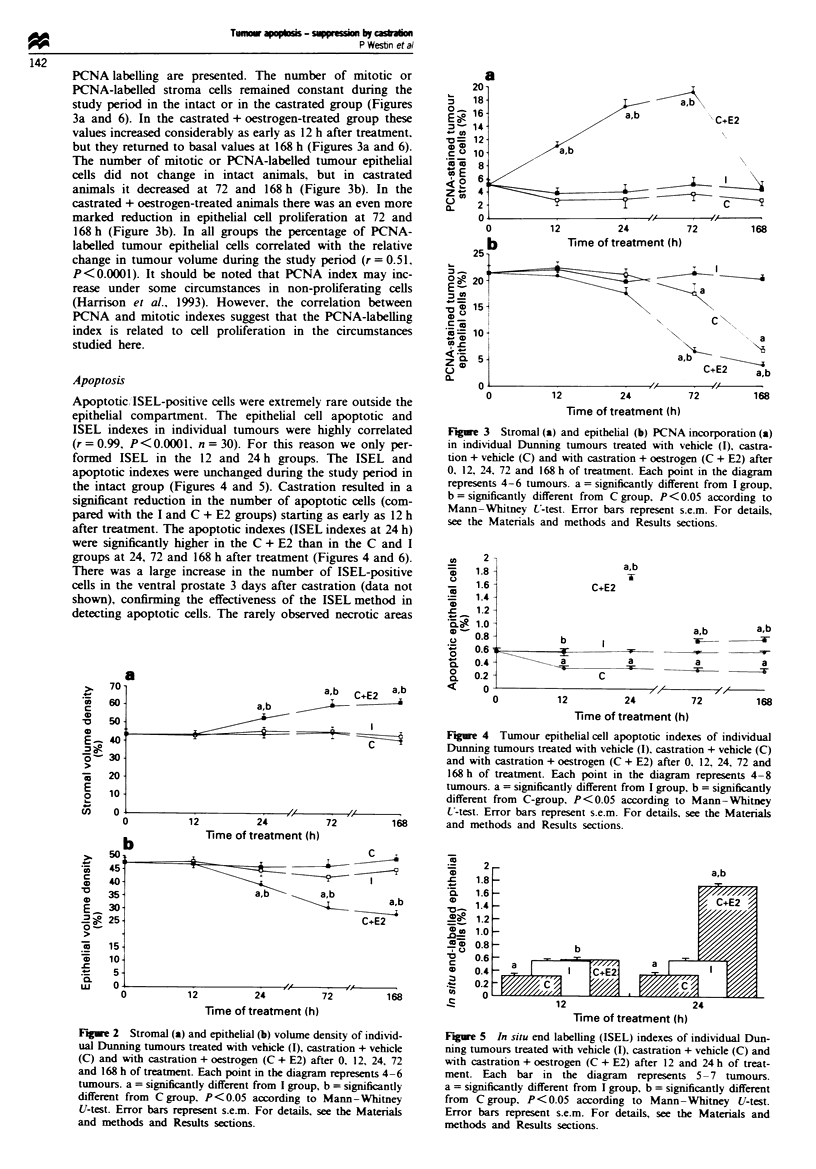

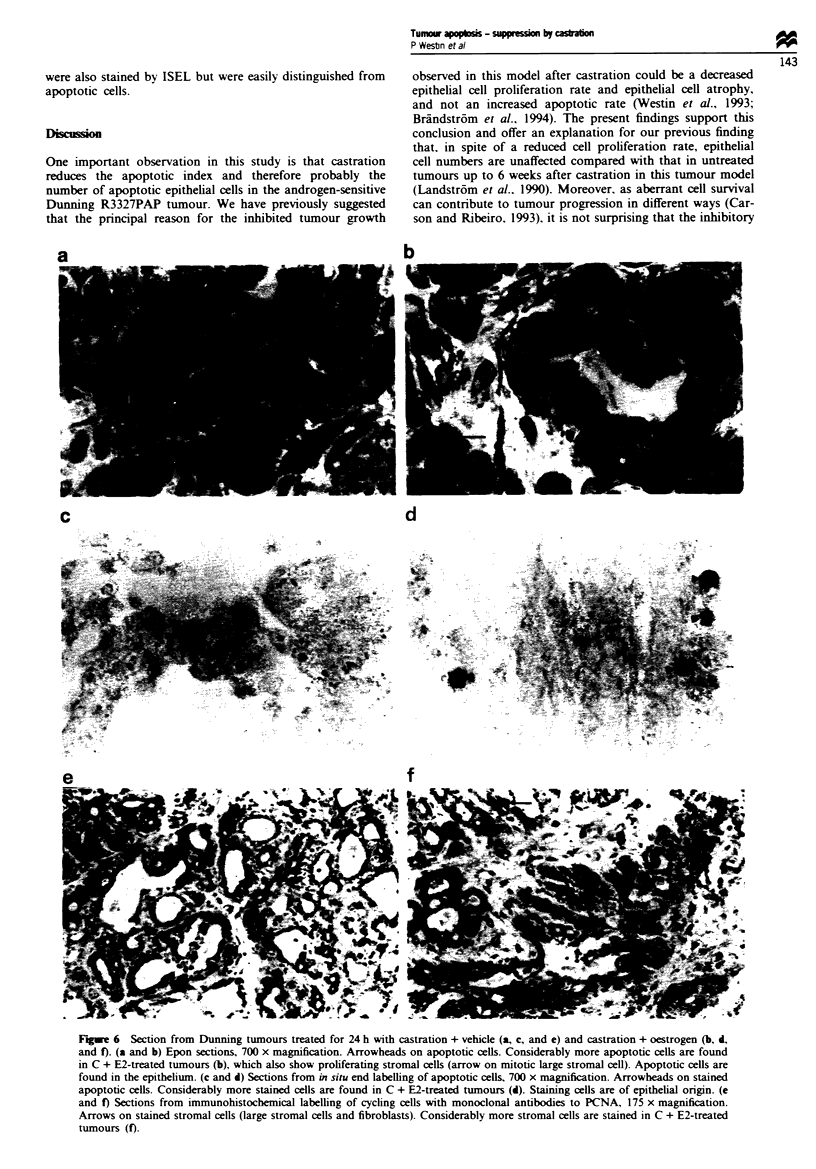

The positive effect of castration in prostatic cancer patients is considered to be related to the induction of apoptosis in androgen-dependent tumour cells. However, castration apparently does not induce apoptosis in the highly differentiated, androgen-sensitive Dunning R3327PAP rat prostatic adenocarcinoma. To elucidate potential mechanisms of apoptotic induction in this tumour model, rats with subcutaneously implanted tumours were treated with vehicle (I), castration+vehicle (C) or castration + 50 micrograms of oestradiol benzoate per day s.c. (C + E2). The effects on tumours were examined by morphometry, in situ end labelling (ISEL) of apoptotic cells and immunohistochemically with monoclonal antibodies to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) at different time points up to 168 h after castration. Castration inhibited tumour growth and decreased the epithelial cell apoptotic rate (from 12 h) and epithelial cell proliferation rate (from 72 h) compared with that in the I group. Tumour volume, volume densities of epithelium and stroma and stroma cell proliferation rate remained constant in the C group during the study period. C + E2 treatment resulted in increases in cell proliferation in the stroma (from 12 h) and in the volume density of stroma (from 24 h) compared with that in the C and I groups. The number of apoptotic epithelial cells was increased (from 24 h), and this was followed by decreases in the volume density of epithelium (from 24 h), the epithelial cell proliferation rate (from 72 h) and the total tumour volume (from 72 h). We conclude that in the Dunning R3327PAP tumour model C + E2 treatment is more effective than castration alone. C+E2 treatment, in contrast to C, is able to induce tumour cell death and to decrease total tumour volume. The mechanism behind this effect is unknown, but it could be related to stimulatory effects of E2 in the tumour stroma.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bacher M., Rausch U., Goebel H. W., Polzar B., Mannherz H. G., Aumüller G. Stromal and epithelial cells from rat ventral prostate during androgen deprivation and estrogen treatment--regulation of transcription. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1993;101(2):78–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman W. C., Jr, Mickey D. D., Fried F. A. Autoradiographic localization of estrogen and androgen target cells in human and rat prostate carcinoma. J Urol. 1985 Apr;133(4):724–728. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändström A., Westin P., Bergh A., Cajander S., Damber J. E. Castration induces apoptosis in the ventral prostate but not in an androgen-sensitive prostatic adenocarcinoma in the rat. Cancer Res. 1994 Jul 1;54(13):3594–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson D. A., Ribeiro J. M. Apoptosis and disease. Lancet. 1993 May 15;341(8855):1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91154-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L. W. Implications of stromal-epithelial interaction in human prostate cancer growth, progression and differentiation. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993 Jun;4(3):183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha G. R., Donjacour A. A., Sugimura Y. Stromal-epithelial interactions and heterogeneity of proliferative activity within the prostate. Biochem Cell Biol. 1986 Jun;64(6):608–614. doi: 10.1139/o86-084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English H. F., Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. Relationship between DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in the programmed cell death in the rat prostate following castration. Prostate. 1989;15(3):233–250. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990150304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesus L., Davies P. J., Piacentini M. Apoptosis: molecular mechanisms in programmed cell death. Eur J Cell Biol. 1991 Dec;56(2):170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch S. M., Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994 Feb;124(4):619–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleave M. E., Hsieh J. T., Wu H. C., von Eschenbach A. C., Chung L. W. Serum prostate specific antigen levels in mice bearing human prostate LNCaP tumors are determined by tumor volume and endocrine and growth factors. Cancer Res. 1992 Mar 15;52(6):1598–1605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R. F., Reynolds G. M., Rowlands D. C. Immunohistochemical evidence for the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) by non-proliferating hepatocytes adjacent to metastatic tumours and in inflammatory conditions. J Pathol. 1993 Oct;171(2):115–122. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J. T. Antagonistic effect of androgen on prostatic cell death. Prostate. 1984;5(5):545–557. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J. T., Coffey D. S. Adaptation versus selection as the mechanism responsible for the relapse of prostatic cancer to androgen ablation therapy as studied in the Dunning R-3327-H adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1981 Dec;41(12 Pt 1):5070–5075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. F., Wyllie A. H., Currie A. R. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972 Aug;26(4):239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M., Bartsch W., Thomsen M., Voigt K. D. Androgens and estrogens: their interaction with stroma and epithelium of human benign prostatic hyperplasia and normal prostate. J Steroid Biochem. 1983 Jul;19(1A):155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., English H. F., Isaacs J. T. Programmed cell death during regression of PC-82 human prostate cancer following androgen ablation. Cancer Res. 1990 Jun 15;50(12):3748–3753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyprianou N., Isaacs J. T. Activation of programmed cell death in the rat ventral prostate after castration. Endocrinology. 1988 Feb;122(2):552–562. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-2-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König J. J., Romijn J. C., Schröder F. H. Prostatic epithelium inhibiting factor (PEIF): organ specificity and production by prostatic fibroblasts. Urol Res. 1987;15(3):145–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00254426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landberg G., Roos G. Antibodies to proliferating cell nuclear antigen as S-phase probes in flow cytometric cell cycle analysis. Cancer Res. 1991 Sep 1;51(17):4570–4574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landström M., Bergh A., Tomic R., Damber J. E. Estrogen treatment combined with castration inhibits tumor growth more effectively than castration alone in the Dunning R3327 rat prostatic adenocarcinoma. Prostate. 1990;17(1):57–68. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland F. S., Chopp R. T., Cosgrove M. D., Howard E. B. Characterization of steroid hormone receptors in the Dunning R-3327 rat prostatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1978 Sep;38(9):2818–2826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith J. E., Jr, Fazeli B., Schwartz M. A. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol Biol Cell. 1993 Sep;4(9):953–961. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.9.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley P., Whitfield J. F., Vanderhyden B. C., Tsang B. K., Schwartz J. L. A new, nongenomic estrogen action: the rapid release of intracellular calcium. Endocrinology. 1992 Sep;131(3):1305–1312. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. C. Social controls on cell survival and cell death. Nature. 1992 Apr 2;356(6368):397–400. doi: 10.1038/356397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan D. Non-hormone chemotherapy for prostate cancer: principles of treatment and application to the testing of new drugs. Semin Oncol. 1988 Aug;15(4):371–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky S. R. The genetic program of cell death. Hypothesis and some applications: transformation, carcinogenesis, ageing. J Theor Biol. 1982 Aug 21;97(4):591–602. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westin P., Bergh A., Damber J. E. Castration rapidly results in a major reduction in epithelial cell numbers in the rat prostate, but not in the highly differentiated Dunning R3327 prostatic adenocarcinoma. Prostate. 1993;22(1):65–74. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijsman J. H., Jonker R. R., Keijzer R., van de Velde C. J., Cornelisse C. J., van Dierendonck J. H. A new method to detect apoptosis in paraffin sections: in situ end-labeling of fragmented DNA. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993 Jan;41(1):7–12. doi: 10.1177/41.1.7678025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G. Q., Bacher M., Friedrichs B., Schmidt W., Rausch U., Goebel H. W., Tuohimaa P., Aumüller G. Functional properties of isolated stroma and epithelium from rat ventral prostate during androgen deprivation and estrogen treatment. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1993;101(2):69–77. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weerden W. M., van Kreuningen A., Elissen N. M., Vermeij M., de Jong F. H., van Steenbrugge G. J., Schröder F. H. Castration-induced changes in morphology, androgen levels, and proliferative activity of human prostate cancer tissue grown in athymic nude mice. Prostate. 1993;23(2):149–164. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990230208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]