Abstract

Antenatal steroids like dexamethasone (DEX) are used to augment foetal lung maturity and there is a major concern that they impair foetal growth. If delivery is delayed after using antenatal DEX, placental function and hence foetal growth may be compromised even further. To investigate the effects of DEX on placental function, we treated 9 pregnant C57/BL6 mice with DEX and 9 pregnant mice were injected with saline to serve as controls. Placental gene expression was studied using microarrays in 3 pairs and other 6 pairs were used to confirm microarray results by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, real-time PCR, in situ hybridization, western blot analysis and Oligo ApopTaq assay. DEX-treated placentas were hydropic, friable, pale, and weighed less (80.0±15.1 mg compared to 85.6.8±7.6 mg, p=0.05) (n=62 placentas). Foetal weight was significantly reduced after DEX use (940±32 mg compared to 1162±79 mg, p=0.001) (n=62 foetuses). There was > 99% similarity within and between the three gene chip data sets. DEX led to down-regulation of 1212 genes and up-regulation of 1382 genes. RT-PCR studies showed that DEX caused a decrease in expression of genes involved in cell division such as cyclins A2, B1, D2, cdk 2, cdk 4 and M-phase protein kinase along with growth-promoting genes such as EGF-R, BMP4 and IGFBP3. Oligo ApopTaq assay and western blot studies showed that DEX-treatment increased apoptosis of trophoblast cells. DEX-treatment led to up-regulation of aquaporin 5 and tryptophan hydroxylase genes as confirmed by real-time PCR, and in situ hybridization studies. Thus antenatal DEX treatment led to a reduction in placental and foetal weight, and this effect was associated with a decreased expression of several growth-promoting genes and increased apoptosis of trophoblast cells.

INTRODUCTION

Corticosteroids are given to mothers who are at risk for preterm delivery to improve survival of the prematurely born infant, by reducing the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, and severe intraventricular haemorrhage [1, 2]. This form of therapy led to improvement in short term [3] and long term outcomes [4, 5] of these infants. Later obstetricians all over the world started using multiple courses of steroids when delivery did not occur after the first course of steroids [6–8]. Multiple courses of corticosteroids did not improve outcome but have been associated with higher incidence of chorioamnionitis, severe IVH, intra-uterine growth restriction and impaired postnatal stress regulation [9, 10]. Based on epidemiologic data, prenatal corticosteroid use has been implicated in long-term programming of the foetus leading to increased risk of cardiovascular, metabolic and neuroendocrine disorders in adult life [11, 12].

Placenta plays a major role in protecting the developing foetus from endogenous maternal steroids during gestation. Though lipophilic fluorinated steroids like dexamethasone (DEX) and betamethasone readily cross the placenta, normally foetal glucocorticoid levels are much lower than maternal levels since placenta acts as a barrier to the transfer of maternal cortisol to the foetus [13]. This barrier function is mediated mainly by two isoforms of an enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and 2 (11β-HSD1 and 11β-HSD2). 11β-HSD1 is a low-affinity reduced NADP(H)-dependent dehydrogenase-oxoreductase which is expressed in glucocorticoid responsive tissues and activates cortisone to cortisol locally. In contrast 11β-HSD2 which is a high-affinity NAD+-dependent unidirectional dehydrogenase converts cortisol into its inactive metabolite cortisone and also inactivates prednisolone in a similar fashion [14, 15]. 11β-HSD2 is highly expressed in human and murine placenta throughout gestation [16, 17]. Babies homozygous or compound heterozygous for inactivating mutations of 11β-HSD2 have been noted to be of low birth weight [18]. Foetus has limited exposure to its own glucocorticoids since endogenous glucocorticoid precursors derived from maternal cholesterol are converted into inactive sulphated compounds in the foetus or transferred back to the placenta rather than continuing down the pathway to cortisol production due to the lack of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) activity in the foetal adrenal gland [19].

There are several reports of deleterious effects of corticosteroids on the developing foetus, but we found a paucity of literature investigating the effects of exogenous steroids on placental function [20–22]. This is important in light of a recent observation that the foetal growth restriction effects of steroids are not seen when steroids are directly administered to the foetus, thus bypassing the placenta [23]. We hypothesize that multiple doses of exogenous glucocorticoids administered to the mother adversely affect placental function and thus are responsible for compromising foetal growth and well being. In this report we have investigated the molecular effects of DEX on murine placenta using microarray analysis, followed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR, real-time quantitative RT-PCR, in situ hybridization, western blot analysis, and trophoblast apoptosis studies.

METHODS

Animals and sample preparation

Eighteen of C57/BL6 mice were mated, pregnancy was timed by appearance of vaginal seminal fluid plug, and that day was designated as day one post-coitus (dpc1). On 15, 16 and 17 dpc, nine pregnant females were injected with dexamethasone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg i.p. and nine pregnant females received equivalent amount of saline to serve as controls. This dose of dexamethasone mimics multiple courses of antenatal steroids. Pregnant female mice were sacrificed on dpc20 (term = dpc21), placenta-foetus pairs were examined; embryo-originated placenta and its membranes were separated from uterine maternal tissues, and weighed. Total RNA was extracted from three controls (C1, C2 and C3) and three dexamethasone-treated (D1, D2 and D3) placentas using TRIZOL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) method. Total protein was prepared from two controls (C4 and C5) and two dexamethasone- treated (D4 and D5) placentas. The sixth to the ninth pair of placentas in each group was used to prepare sections for histology, apoptosis and in-situ hybridization studies. All studies were performed in accordance with the “Guide for the care and use of Laboratory Animals” as adopted by the Medical College of Georgia.

Microarray gene expression analysis

RNA samples from three independent experiments, C1 to C3 and D1 to D3, were subjected to analysis by Affymetrix high-density oligonucleotide arrays by using 430A 2.0 mouse genome array chips which houses transcripts of 24,000 genes (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Probe synthesis and microarray hybridization were performed according to standard Affymetrix protocols. The microarray experiments were executed three times by using three independent dsRNA preparations. Gene chip data was analyzed using GeneSpring 6.0 software (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA, USA) according to method previously described [24]. The gene chip data was later categorized into groups based on biological functions and raw data submitted to GEO website with accession number GSE 4165 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Several of the genes with well described biological function, and which were up- or down-regulated > 2 folds were selected for further analysis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR to confirm our microarray data.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Primers were designed using Oligo® primer analysis software 6.0 (National Biosciences Inc. Cascade, CO, USA). The nucleotide sequence of the primers used for RT-PCR studies are shown in Table 2. One microgram each of the total RNA from the dexamethasone-treated and the saline-treated control placentas was reverse transcribed with random hexamers and reagents from RNA PCR kit (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) in a total volume of 20 μl. Consecutive PCR was performed using 1–5 μl of cDNA as template using standard methods. The expression of candidate genes was normalized using the expression levels of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase-1 (HPRT) [25]. Amplification was carried out for 10 min at 96°C, followed by 30 cycles for 1 min at 95°C, for 1 min at 55°C, and for 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were visualized on 1.2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and densitometry was performed using a SpectraImager 5000 Imaging system and AlphaEase 32-bit software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA). Densitometry data (mean ± SEM) were plotted to represent relative expression of each gene.

Table 2.

Primers used for semi-quantitative RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR studies

| Accession Number | Molecule | Amplicon size (bp) | Sense primer | Antisense primer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_184052 | IGF-1 | 233 | TGA GCT GGT GGA TGC TCT TCA GTT | TCT GAG TCT TGG GCA TGT CAG TGT |

| NM_010513 | IGF-1R | 250 | TGA AGC TGA GAA GCA GGC TGA GAA | ATC CTC GAC TTG CGA CCC GTA TTT |

| NM_010514 | IGF-2 | 434 | TTC TCA TCT CTT TGG CCT TCG CCT | ACG ATG ACG TTT GGC CTC TCT GAA |

| NM_008343 | IGFBP-3 | 407 | TCC AGG AAA CAT CAG TGA GTC CGA | CAT ACT TGT CCA CAC ACC AGC AGA |

| BC060741 | EGF-R | 455 | AAT CAC GGC TGT ACT CTT GGG TGT | ATC GCT CCC TCC AAC AAC AGA CTT |

| X56848 | BMP-4 | 515 | AAC CTC AGC AGC ATC CCA GAG AAT | AGT TGA GGT CAG CCA GTG GAA |

| BC046336 | cdk 4 | 458 | CAA TGT TGT ACG GCT GAT GGA TGT | GGT CGG CTT CAG AGT TTC CAC AGA |

| BC049086 | cyclin D2 | 487 | ACC TCC CGC AGT GTT CCT ATT TCA | GGC GGG TAC ATG GCA AAC TTG A |

| X75483 | cyclin A2 | 500 | GAC TCG ACG GGT TGC TC | CAG CCA AAT GCA GGG TCT CAT |

| BC080202 | cyclin B1 | 469 | CGC TCA GGG TCA CTA GGA AC | CCA CTA TCT GCG TCT ACG TCA CTC |

| BC037662 | cyclin F | 730 | GTG TGC CAA GTG TTT CTG TTA TC | TTT CGC AGC GTA GTC CCT GT |

| BC005654 | cdk2 | 578 | TAA GAA GAT CCG GCT CGA CAC TGA | AGG AGC ACA GCG GGC AGA GAC T |

| AF002823 | M-Prot kinase | 674 | GAA CGG CAG CAT ATT AGT AG | TTC TTG AAC GCT TAT ATT CTG AAA |

| Real-time PCR Primer set | ||||

| NM_009701 | aquaporin 5 | 180 | GCC ACC CTC ATC TTC GTC TTC TTT | TGG TTG CCT ATT AAG AGG GCC AGA |

| NM_009414 | tryptophan hydoxylase | 195 | ATT TGT TGA CTG CGA CAT CAG CCG | TGC GAT CCA AAC AGC ACT CTG |

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

Quantitative PCR was performed to confirm microarray data for two highly up-regulated genes; aquaporin 5 (NM_009701) and tryptophan hydroxylase (NM_009414), which produced two amplicons of 180 and 195 bp each, respectively. Primers were designed using IDT primer quest software available online (Integrated DNA technologies, Skokie, IL, USA) (Table 2). One μg each of the total RNA from the dexamethasone-treated and the saline-treated control placentas was reverse transcribed with random hexamers and reagents from RNA PCR kit (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA) in a total volume of 20 μl. Real-time PCR was performed using a BioRad iQ iCycler Detection System (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with SYBR green fluorophore. Reactions were performed in a total volume of 25 μL, which included 12.5 μL 2x SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), 1 μL of each primer at 5μM concentration, and 1 μL of the previously reverse-transcribed cDNA template and 9.5 μL of dH2O. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: an initial incubation at 95 °C for 10 min was followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s, and a final incubation at 72 °C for 5 min.

Expression of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase-1 (HPRT) was used as an internal control to determine the quantity of the target gene-specific transcripts present in DEX-treated samples relative to controls. Ct values were first normalized by subtracting the Ct value obtained from the HPRT control (ΔCt DEX = Ct DEX − Ct HPRT and ΔCt Control = Ct Control − Ct HPRT). The concentration of gene-specific mRNA in DEX-treated samples relative to control samples was calculated by subtracting the normalized ΔCt values obtained for control samples from those obtained from DEX-treated samples (ΔΔCt=ΔCt DEX − ΔCt control) and the relative concentration was determined as 2−ΔΔCt. Real-time PCR reaction was carried out in duplicate for each of the 3 control and DEX-treated placentas (n=6 in each group), (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for aquaporin 5 and tryptophan hydroxylase.

DEX-treatment led to up-regulation of aquaporin 5 gene by 23 folds and tryptophan hydroxylase gene by 12 folds (n=6 in each group). * represents statistically significant change in expression.

In situ hybridization

Aquaporin 5 gene expression was studied by in situ hybridization according to method described by others [26]. For the preparation of antisense and sense (negative control) riboprobes, a 549 bp nucleotide fragment corresponding to nucleotide sequence 5-553 of the aquaporin 5 cDNA (accession number NM_009701) was cloned into pGEM-T vector. The size of the cloned insert was confirmed after digestion with EcoR1 enzyme and sequencing. The probes were then prepared by in vitro transcription using the DIG nucleic acid detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with appropriate RNA polymerases (T7 RNA polymerase for the sense probe and SP6 RNA polymerase for the antisense probe) after linearizing the plasmid with SalI for the sense probe and SacII for the antisense probe.

Apoptosis assay

Placental trophoblast apoptosis was studied by ApopTag In Situ Oligo Ligation (ISOL) technique with T4 DNA ligase (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). T4 DNA ligase covalently joins complementary ends of a pair of double-stranded DNA molecules produced during the apoptotic process. The ends to be joined are those of the genomic DNA in the sample and those of the synthetic, biotinylated oligonucleotide in the ISOL kit. Detection was subsequently performed by binding the streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. Peroxidase was localized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the substrate. Frozen placental sections were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. These were then washed in PBS and fixed in an alcohol-acetate (2:1) solution for 5 min at −20° C. After washing again in PBS, hydrogen peroxide was added for 5 min at room temperature. The samples were washed with PBS and incubated with T4 DNA ligase and oligo A. The ligation reaction was carried out overnight at 16° C in a humidified chamber. The samples were then washed and the Streptavidin-Peroxidase reaction was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). After 10 min at room temperature, the slides were counterstained with haematoxylin, and dehydrated before viewing under a light microscope.

Western blot analyses

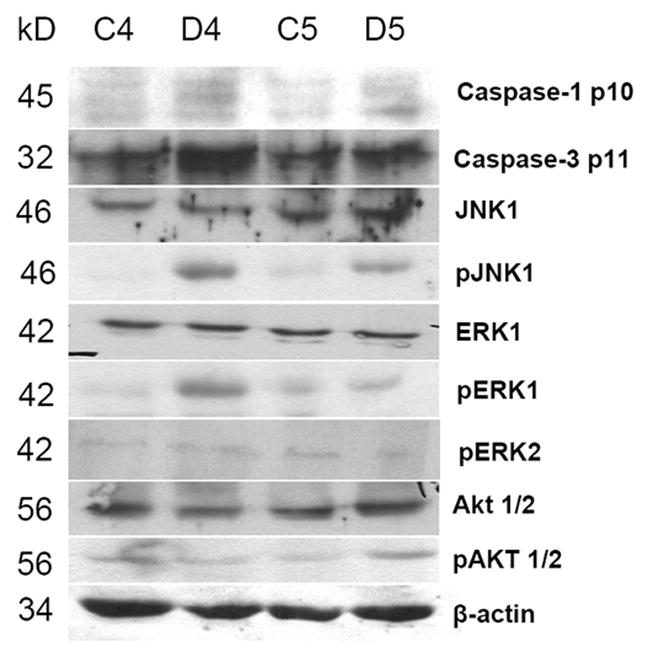

50 to 100 mg of placental tissue, free of maternal blood, was homogenized, using a polytron, in RIPA buffer (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 150 mM sodium chloride, 1.0% Igepal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS with Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein concentration was measured by the Lowry method. Twenty five μg of protein was analyzed by immunoblotting using 10% SDS-PAGE. The blots were blocked for 1.5 h at room temperature with TRIS-buffered saline/0.05% Tween–20 containing 5% non-fat milk, washed with PBS-T, and subsequently incubated with commercially available polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) against activated caspase 1 p10, caspase 3 p11, c-jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK1 and pJNK1), extracellular-signal related kinase 1 (ERK1 and pERK1/2), serine/threonine kinases (Akt1/2 and pAkt1/2) and β-actin (1:500, overnight incubation at 4°C). This was followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody for 1.5 h. Positive signals were visualized by a chemiluminescence assay using ECL Western blot detection system kit as per manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ 08855, USA). Three sets of blots were prepared for each sample and Figure 3 shows a representative image for each blot.

Figure 3. Representative western blot from two control and two DEX-exposed placentas.

There was increased expression of caspases 1 p10 and caspase 3 p11, along with pJNK1, pERK1 but no change in expression of serine/threonine kinase Akt or pAkt. β-actin served as internal control.

RESULTS

DEX induces apoptosis of trophoblast cells and intra-uterine growth retardation

DEX had a profound effect on the mouse placentas; there were noticeable gross changes in the DEX-treated placentas (Figure 1A). DEX-treated placentas were hydropic, pale, friable and weighed less (DEX-treated 80.0±15.1 mg; saline-treated 85.6±7.6 mg, p=0.05; n=62 placentas). DEX-treatment was not associated with foetal death. Microscopic examination of DEX-treated placentas showed swollen trophoblast cells in both the junctional and labyrinth zones (Figure 1B and 1C), with loss of trophoblast cells in the junctional zone (Figure 1B, empty space outlined by arrowheads). Foetal weight was significantly reduced after DEX treatment (940±32 mg compared to 1162±79 mg; p=0.001; n=62 foetuses). DEX treatment caused trophoblast apoptosis as studied by ApopTaq In Situ Oligo Ligation (ISOL) technique (Figure 1D and 1E). Panel D shows a representative DEX-treated placenta, a marked increase in apoptosis-positive nuclei of trophoblast cells (large arrowheads) is evident in this section compared to a control placenta with few apoptosis-positive nuclei (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Gross and microscopic appearance of saline and DEX treated placentas and Oligo-ApopTag assay showing trophoblast apoptosis.

Panel A shows gross appearance of saline and DEX treated placentas. Panels B and C are haematoxylene and eosine stained sections of placentas, control placenta in panel C has a well defined layers of junctional trophoblast cells (small arrow) and labyrinthine trophoblast cells (large arrow) in contrast DEX treated placenta in panel B show loss of trophoblast cells mainly in the junctional zone as outlined by small arrowheads. Bar represents 100 μm. Panel D and E represents Oligo-ApopTaq assay to study trophoblast apoptosis. There is marked increase in apoptotic nuclei (large arrows) in DEX-exposed placenta (panel D) compared to saline-exposed control placenta (panel E).

Bar represents 50 μm.

DEX treatment leads to differential gene expression

Microarray analysis showed that DEX treatment led to down-regulation of 1212 genes (Table 1 shows 12 representative genes) and up-regulation of 1382 genes (Table 1 shows 12 representative genes) in the mouse placenta. Among the three controls (C1, C2 and C3) and the three DEX-treated placentas (D1, D2 and D3), 98% of the genes showed a similar expression pattern with minimal variation within each set of three samples. Genes which were up- or down-regulated > 2 fold were classified into functional groups based on their known biological role. Table 1 shows 12 growth-related genes which were down-regulated, with their respective accession numbers and fold change in expression after DEX treatment. Raw data in MIAME format (Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment) from these six gene chip experiments were uploaded on the GEO web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with accession No. GSE 4165. This facilitates the unambiguous interpretation of the data and potential verification of our conclusions by other investigators interested in replicating findings from this study. We studied several genes which were up- or down-regulated by antenatal DEX-treatment by other methods but did not have the resources to study all the 2592 genes. Further analysis of our gene expression data, done by categorizing them into functional groups, revealed that DEX affected the expression of a wide-range of genes relevant to placental function. DEX treatment led to down-regulation of genes involved in cell growth, protein biosynthesis, skeletal development, and collagen metabolism. There was also decreased expression of genes involved in cell division, DNA replication, chromosome segregation, DNA alkylation, nucleotide and nucleoside biosynthesis and microtubule-based processes. We also found a generalized decrease in genes involved in B-cell activation and differentiation, innate immune response, antigen processing and presentation, and complement system. A mixed response was seen on genes regulating glucose, cholesterol and steroid metabolism (data not shown).

Table 1.

Relative expression of placental genes which were either down- or up-regulated by DEX-treatment.

| Affymetrix ID | Accession No. | Mean fold Change | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1424046_at | AF002823 | −22.4 | M phase protein kinase |

| 1416076_at | X58708 | −11.9 | Cyclin B1 |

| 1460347_at | BC011074 | −9.9 | keratin 14 |

| 1427276_at | BI665568 | −7.6 | zinc finger protein |

| 1418091_at | NM_023755 | −6.5 | CRTR-1 |

| 1448314_at | NM_007659 | −5.4 | cdk2 |

| 1452954_at | AV162459 | −5.3 | ubiquitin conjugating enzyme |

| 1422513_at | NM_00763 | −5.2 | Cyclin F1 |

| 1417911_at | X75483 | −4.8 | Cyclin A2 |

| 1449038_at | NM_008288 | −4.4 | 11 β-HSD1 |

| 1422912_at | NM_028770 | −1.8 | BMP-4 |

| 1460420_a_at | AF277898 | −1.6 | EGF-R |

| 1418818_at | NM_009701 | 28 | aquaporin 5 |

| 1419524_at | NM_009414 | 26 | tryptophan hydoroxylase |

| 1423439_at | AW106963 | 23 | PEPCK-1 cytosolic |

| 1421999_at | U02601 | 12 | TSH receptor |

| 1425155_at | M21149 | 12 | macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| 1460693_at | BG074456 | 10.5 | procollagen type IX |

| 1423556_at | AV021656 | 9.2 | aldo-keto reductase B7 |

| 1449478_at | NM_010810 | 5.6 | matrix mettaoproteinase 7 |

| 1423954_at | K02782 | 5.6 | complement component 3 |

| 1427372_at | BM119774 | 5.3 | 25-OH Vit D3 1-α hydoroxylase |

| 1450682_at | NM_008375 | 5.3 | FATP-6 |

| 1416761_at | BC014753 | 4.9 | 11 β-HSD2 |

cdk2-Cyclin dependent kinase2; CRTR-1- transcriptional repressor related to the CP2 family of transcription factors; 11β-HSD1-11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase1; BMP-4-bone morphogenic protein-4; EGF-R-epithelial growth factor-receptor; PEPCK-1-phosphoenolpyruvate kinase-1; FATP-6-fatty acid transport protein-6; 11β-HSD2-11β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase2.

DEX treatment down-regulates cell growth-related genes

Based on microarray data, 12 growth-related genes were chosen to study their relative expression in control and DEX-treated placentas using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. RT-PCR studies confirmed microarray data that DEX treatment led to down-regulation of several genes (Table 1) such as cyclins B1, D2 and F1 along with M phase protein kinase, cdk2 and cdk4 (Figure 2). We did not find a significant difference in expression of insulin-like growth factor 1, 2 (IGF-1 and2) and its receptor (IGF-R) genes (data not shown), but there was down-regulation of two other key molecules required for trophoblast and foetal growth, bone morphogenic protein-4 (BMP-4), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR.

There was down-regulation of cyclin B1, D2, F1 along with MC protein kinase, cdk2, cdk4 and epithelial growth factor receptor (EGF-R), and bone morphogenic protein-4 (BMP-4) after DEX-treatment. Expression of HPRT was used to normalise data from each group and * represents statistically significant change in expression.

DEX treatment leads to activation caspase-1, caspase-3 and mitogen-activated protein kinases

Figure 3 is a composite image of western blots from a set of two samples showing activation of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in placental trophoblast cells after DEX treatment. There was also increased phosphorylation of c-jun N-terminal kinase 1 (pJNK1), and extracellular signal-related kinase 1 (pERK1); but no activation of serine/threonine kinase Akt was noted in response to DEX treatment. β-Actin served as internal control.

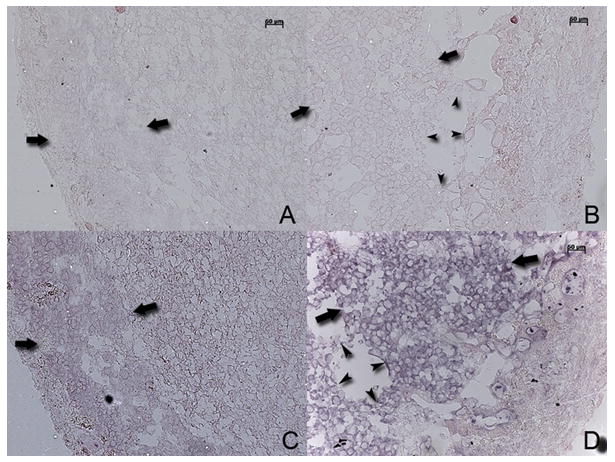

DEX treatment increases the expression of aquaporin 5 and tryptophan hydroxylase

Aquaporin 5 and tryptophan hydroxylase genes were highly up-regulated after DEX-treatment (Table 1) so we chose to confirm this finding with real-time PCR studies (Figure 4). We found similarity between microarray and real-time PCR expression data though the numerical values for fold change in expression varied between the two experiments (Figure 4). Expression of aquaporin 5 was also studied in control and DEX treated placentas by in situ hybridization studies to localize the site of expression. Panel A (sense probe) and panel C (antisense probe) from control placentas show basal expression of aquaporin 5 and panel B (sense probe) and panel D (antisense probe) from DEX-treated placenta show enhanced expression of aquaporin 5 in the trophoblast cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5. In situ hybridization study to show expression pattern of aquaporin 5.

Panel A and C are control placentas, panel A is hybridized with a sense probe and panel C with antisense probe. Panels B and D are DEX-exposed placenta hybridized with a sense and antisense probes respectively. Large arrows indicate junctional trophoblast cell layer and arrow heads delineate areas of loss of trophoblast cells in panels B and D of DEX-treated placentas. Bar represents 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this report of a late murine placenta model, we have shown that use of multiple doses of antenatal DEX leads to change in gene expression. Antenatal DEX use was associated with reduction in foetal and placental weight with morphological changes in the placenta. We found that several genes which are considered critical for foetal growth were down-regulated which may be responsible for the observed decrease in foetal birth weight.

There is overwhelming evidence that a single course of antenatal glucocorticoids given to mothers prior to early preterm birth reduces morbidity and mortality in the newborn, thus making this practice a standard of care [1, 4]. If these mothers remain undelivered after a week of therapy with steroids, some practitioners use repeated courses in the belief that effect of previous dose has worn off even though there is no scientific basis to support this practice [6, 27–29]. Long-term follow up studies of infants born after use of a single course of antenatal steroids have not shown any deleterious effects on survivors [4, 5, 30, 31] but there is substantial body of evidence from animal [32–34] and human studies that repeated courses of steroids offer no advantage and may even be harmful for the mother as well as the newborn [10, 35, 36].

Human and murine placentas are both haemochorial in nature where more chorio-allantoic tissue creating the placental barrier separates the maternal and foetal blood circulations. The villous architecture in the human placenta is tree-like compared to a labyrinth or a maze-like pattern in the mouse placenta. The expression pattern of genes for transcription factors and growth-related molecules has been reported to be similar between human and the mouse placenta [37]. Mouse steroid metabolism also differs from humans, in that the active glucocorticoid in the former is corticosterone, whereas cortisol serves as the active glucocorticoid in humans [19, 38].

Antenatal DEX not only passes through the placenta to cause varied biological effects on the developing foetus but also alter placental trophoblast function as evident by the results of our investigation. Even though pregnancy may continue after a course of steroids, placental dysfunction sets in which leads to further compromise of foetal growth. This effect has been shown in animal studies where maternal injection of betamethasone led to foetal growth restriction but no such adverse effects were seen if the same dose of betamethasone was directly injected into the growing sheep foetal circulation [23]. Here we have shown that in late pregnancy DEX leads to marked changes in the morphology and gene expression profile in the placenta with an associated reduction in foetal weight. These findings are strengthened by several clinical observations in humans that inactivating mutations in 11β-HSD2 gene which helps the placenta inactivate maternal cortisol, lead to intrauterine foetal growth restriction, postnatal growth failure, juvenile hypertension, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, and hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism [18, 39, 40]. DEX, a long-acting fluorinated glucocorticoid, triggers its immediate biological actions through a non-genomic mechanism mediated through calcium signalling but produces its long-term effects through changes in gene expression, mediated via glucocorticoid receptors [41].

RT-PCR studies confirmed the gene expression data obtained by microarray analysis for specific genes, including those involved in the control of cell cycle (e.g. cyclins). Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases regulate the transition from one phase of cell cycle to the next and play a critical role in foetal and placental development [42]. Cyclin D is associated with G1 phase, cyclins A and E with S phase of cell division, and cyclin A and B with mitosis. These genes are critical for cell division and control the entry of cell from one phase of cell division to the next. Steroids control the rate of cell cycle progression by regulating the expression of cyclins and cyclin- dependent kinase genes and have been used in cancer chemotherapy [43]. Modulation of cyclins and cdk’s are implicated in foetal growth restriction due to utero-placental insufficiency [44, 45].

Antenatal DEX leads to a noticeable increase in trophoblast apoptosis, and this has been reported in rat placentas [22]. Apoptosis is increased in human pregnancies complicated by foetal growth restriction, suggesting that it is a key factor in the overall control of foeto-placental growth [46]. DEX-induced trophoblast apoptosis was mediated through activation of caspases 1 and 3 (Figure 3). ERK1/2 and JNK are two critical components of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase) cascades and control cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [47]. We found that DEX treatment led to ERK1 and JNK1 activation by their phosphorylation and these constitute strong pro-apoptotic signals. We found no change in activation of serine/threonine kinase B (Akt) after DEX treatment which are considered anti-apoptotic molecules [48].

Placenta expresses aquaporins 1, 3, 8 and 9 and aquaporin 5 is normally expressed in the lung and salivary gland and plays a critical role in regulation of cell volume in response to changes in osmolarity [49]. Aquaporin 5 expression has been shown to be enhanced by steroids in other tissues, thus this may be the reason for its increased expression in the DEX-exposed placentas and may explain the hydropic appearance of these placentas. Tryptophan hydroxylase is the key regulatory enzyme required for serotonin biosynthesis. Serotonin is a potent vasoconstrictor, and up-regulation of serotonin production may have deleterious effects on placental blood supply and there has been a major concern that use of fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor during pregnancy affects foetal growth and development. [50, 51]. PEPCK is a key regulator of gluconeogenesis and hyperglycemia is a well-known side effect of steroid use. Antenatal DEX treatment has been shown to up-regulate hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha which in turn up-regulates PEPCK gene and this phenomenon has been linked to prenatal foetal programming and hyperglycemia later in life [52].

We conducted this investigation in a mouse model to study the differences in gene expression in placenta in response to maternal antenatal DEX treatment to obtain a global genome-wide picture. This is the first report of molecular effects of exogenous steroid use on the placenta in an animal model. We chose to study mouse placenta since it allowed us to control variations commonly seen in maternal conditions such as gestational age, genetic background, maternal infections and other factors associated with preterm onset of labour. Our study has uncovered several important molecular and biological changes in the placenta as a result of DEX exposure in this animal model. These findings suggest that similar studies of the effects of antenatal steroid therapy on placental function and foetal growth in humans are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part NIH grant HD 048867 and by a combined intramural grant program grant of University system of Georgia. We are grateful to Profs. William Rainey, PhD and Puttur D Prasad, PhD for their useful comments and critique.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Crowley P. Prophylactic corticosteroids for preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD000065. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Obstetric P. ACOG committee opnion: antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:871–873. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moise AA, Wearden ME, Kozinetz CA, Gest AL, Welty SE, Hansen TN. Antenatal steroids are associated with less need for blood pressure support in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 1995;95:845–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle LW, Ford GW, Rickards AL, Kelly EA, Davis NM, Callanan C, Olinsky A. Antenatal corticosteroids and outcome at 14 years of age in children with birth weight less than 1501 grams. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E2. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaap AH, Wolf H, Bruinse HW, Smolders-De Haas H, Van Ertbruggen I, Treffers PE. Effects of antenatal corticosteroid administration on mortality and long-term morbidity in early preterm, growth-restricted infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:954–960. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorp JA, Jones AM, Hunt C, Clark R. The effect of multidose antenatal betamethasone on maternal and infant outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:196–202. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.108859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walfisch A, Hallak M, Mazor M. Multiple courses of antenatal steroids: risks and benefits. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newnham JP, Moss TJ. Antenatal glucocorticoids and growth: single versus multiple doses in animal and human studies. Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:285–292. doi: 10.1053/siny.2001.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MJ, Davies J, Guinn D, Sullivan L, Atkinson MW, McGregor S, Parilla BV, Hanlon-Lundberg K, Simpson L, Stone J, Wing D, Ogasawara K, Muraskas J. Single versus weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:274–281. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000110249.84858.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorp JA, Jones PG, Knox E, Clark RH. Does antenatal corticosteroid therapy affect birth weight and head circumference? Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spinillo A, Viazzo F, Colleoni R, Chiara A, Maria Cerbo R, Fazzi E. Two-year infant neurodevelopmental outcome after single or multiple antenatal courses of corticosteroids to prevent complications of prematurity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Regan D, Kenyon CJ, Seckl JR, Holmes MC. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation in the rat permanently programs gender-specific differences in adult cardiovascular and metabolic physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E863–870. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00137.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benediktsson R, Calder AA, Edwards CR, Seckl JR. Placental 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: a key regulator of fetal glucocorticoid exposure. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997;46:161–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.1230939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michael AE, Thurston LM, Rae MT. Glucocorticoid metabolism and reproduction: a tale of two enzymes. Reproduction. 2003;126:425–441. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diederich S, Eigendorff E, Burkhardt P, Quinkler M, Bumke-Vogt C, Rochel M, Seidelmann D, Esperling P, Oelkers W, Bahr V. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase types 1 and 2: an important pharmacokinetic determinant for the activity of synthetic mineralo- and glucocorticoids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5695–5701. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart PM, Rogerson FM, Mason JI. Type 2 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase messenger ribonucleic acid and activity in human placenta and fetal membranes: its relationship to birth weight and putative role in fetal adrenal steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:885–890. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.3.7883847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomlinson JW, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Draper N, Lavery GG, Cooper MS, Hewison M, Stewart PM. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: a tissue-specific regulator of glucocorticoid response. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:831–866. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dave-Sharma S, Wilson RC, Harbison MD, Newfield R, Azar MR, Krozowski ZS, Funder JW, Shackleton CH, Bradlow HL, Wei JQ, Hertecant J, Moran A, Neiberger RE, Balfe JW, Fattah A, Daneman D, Akkurt HI, De Santis C, New MI. Examination of genotype and phenotype relationships in 14 patients with apparent mineralocorticoid excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2244–2254. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallen CB. Steroid hormone synthesis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004;31:795–816. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ain R, Canham LN, Soares MJ. Dexamethasone-induced intrauterine growth restriction impacts the placental prolactin family, insulin-like growth factor-II and the Akt signaling pathway. J Endocrinol. 2005;185:253–263. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy VE, Fittock RJ, Zarzycki PK, Delahunty MM, Smith R, Clifton VL. Metabolism of Synthetic Steroids by the Human Placenta. Placenta. 2007;28:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell BJ, Hisheh S, Dharmarajan AM, Burton PJ. Apoptosis in rat placenta is zone-dependent and stimulated by glucocorticoids. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1913–1917. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newnham JP, Evans SF, Godfrey M, Huang W, Ikegami M, Jobe A. Maternal, but not fetal, administration of corticosteroids restricts fetal growth. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8:81–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199905/06)8:3<81::AID-MFM3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allison DB, Cui X, Page GP, Sabripour M. Microarray data analysis: from disarray to consolidation and consensus. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrg1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Kok JB, Roelofs RW, Giesendorf BA, Pennings JL, Waas ET, Feuth T, Swinkels DW, Span PN. Normalization of gene expression measurements in tumor tissues: comparison of 13 endogenous control genes. Lab Invest. 2005;85:154–159. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srinivas SR, Gopal E, Zhuang L, Itagaki S, Martin PM, Fei YJ, Ganapathy V, Prasad PD. Cloning and functional identification of slc5a12 as a sodium-coupled low-affinity transporter for monocarboxylates (SMCT2) Biochem J. 2005;392:655–664. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley P. Antenatal corticosteroids--current thinking. Bjog. 2003;110(Suppl 20):77–78. doi: 10.1016/s1470-0328(03)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung TN, Lam PM, Ng PC, Lau TK. Repeated courses of antenatal corticosteroids: is it justified? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:589–596. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newnham JP, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Sloboda DM. Antenatal corticosteroids: the good, the bad and the unknown. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:607–612. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle LW, Kitchen WH, Ford GW, Rickards AL, Lissenden JV, Ryan MM. Effects of antenatal steroid therapy on mortality and morbidity in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr. 1986;108:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)81006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arad I, Durkin MS, Hinton VJ, Kuhn L, Chiriboga C, Kuban K, Bellinger D. Long-term cognitive benefits of antenatal corticosteroids for prematurely born children with cranial ultrasound abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:818–825. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutzler MA, Ruane EK, Coksaygan T, Vincent SE, Nathanielsz PW. Effects of three courses of maternally administered dexamethasone at 0.7, 0.75, and 0.8 of gestation on prenatal and postnatal growth in sheep. Pediatrics. 2004;113:313–319. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coe CL, Lubach GR. Developmental consequences of antenatal dexamethasone treatment in nonhuman primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uno H, Eisele S, Sakai A, Shelton S, Baker E, DeJesus O, Holden J. Neurotoxicity of glucocorticoids in the primate brain. Horm Behav. 1994;28:336–348. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bloom SL, Sheffield JS, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Antenatal dexamethasone and decreased birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:485–490. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seckl JR. Prenatal glucocorticoids and long-term programming. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151(Suppl 3):U49–U62. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151u049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Georgiades P, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ. Comparative developmental anatomy of the murine and human definitive placentae. Placenta. 2002;23:3–19. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanford AT, Murphy BE. In vitro metabolism of prednisolone, dexamethasone, betamethasone, and cortisol by the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;127:264–267. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson RC, Dave-Sharma S, Wei JQ, Obeyesekere VR, Li K, Ferrari P, Krozowski ZS, Shackleton CH, Bradlow L, Wiens T, New MI. A genetic defect resulting in mild low-renin hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10200–10205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ugrasbul F, Wiens T, Rubinstein P, New MI, Wilson RC. Prevalence of mild apparent mineralocorticoid excess in Mennonites. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4735–4738. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Losel R, Wehling M. Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrm1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell. 2004;116:221–234. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musgrove EA. Cyclins: roles in mitogenic signaling and oncogenic transformation. Growth Factors. 2006;24:13–19. doi: 10.1080/08977190500361812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baserga M, Hale MA, McKnight RA, Yu X, Callaway CW, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency alters hepatic expression, phosphorylation, and activity of the glucocorticoid receptor in fetal IUGR rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1348–R1353. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00211.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tetzlaff MT, Bai C, Finegold M, Wilson J, Harper JW, Mahon KA, Elledge SJ. Cyclin F disruption compromises placental development and affects normal cell cycle execution. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2487–2498. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2487-2498.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straszewski-Chavez SL, Abrahams VM, Mor G. The role of apoptosis in the regulation of trophoblast survival and differentiation during pregnancy. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:877–897. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y, Wang Q, Evers BM, Chung DH. Signal transduction pathways involved in oxidative stress-induced intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1192–1197. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000185133.65966.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langdown ML, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Early growth retardation induced by excessive exposure to glucocorticoids in utero selectively increases cardiac GLUT1 protein expression and Akt/protein kinase B activity in adulthood. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:11–22. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Y, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-5 dependent fluid secretion in airway submucosal glands. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41288–41292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watts SW. 5-HT in systemic hypertension: foe, friend or fantasy? Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108:399–412. doi: 10.1042/CS20040364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrison JL, Riggs KW, Rurak DW. Fluoxetine during pregnancy: impact on fetal development. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2005;17:641–650. doi: 10.1071/rd05030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nyirenda MJ, Dean S, Lyons V, Chapman KE, Seckl JR. Prenatal programming of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha in the rat: A key mechanism in the ‘foetal origins of hyperglycaemia’? Diabetologia. 2006;49:1412–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]