Abstract

We examined the susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi to antimicrobial peptides likely to be encountered in vivo during human infection. H. ducreyi was significantly more resistant than Escherichia coli to the bactericidal effects of all peptides tested. Class I and II H. ducreyi strains exhibited similar levels of resistance to antimicrobial peptides.

Haemophilus ducreyi, an extracellular pathogen of human skin, encounters several cell types during human infection, including neutrophils, macrophages, and keratinocytes (3-5) that secrete cationic antimicrobial peptides (APs) (recently reviewed in reference 10). APs secreted by neutrophils include the α-defensins human neutrophil peptides 1 to 4 (HNP-1 to -4) and cathelicidin LL-37 (1, 7). Macrophages secrete human β-defensin 1 (HBD-1) and HBD-2 and LL-37, and keratinocytes secrete HBD-1 to -4 and LL-37 (1, 9, 21). Vaginal epithelial cells also secrete the α-defensin human defensin 5 (HD-5) (14, 15). We previously demonstrated that HNP-1 to -3 are present within natural chancroidal ulcers (5). Because H. ducreyi multiplies in an environment with APs, we hypothesized that H. ducreyi resists the bactericidal effects of human APs encountered in vivo.

Bactericidal assay.

H. ducreyi 35000HP and Escherichia coli ML35 and their growth conditions have been described previously (2, 8, 12). Protegrin 1 (PG-1) was provided by Robert I. Lehrer. Other APs were purchased from PeproTech (HNP-1, HBD-2, and HBD-3) (Rocky Hill, NJ), Sigma Aldrich (HNP-2) (St. Louis, MO), Peptides International (HNP-3 and HD-5) (Louisville, KY), AnaSpec (HBD-4) (San Jose, CA), and Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (LL-37) (Belmont, CA).

Mid-logarithmic-phase bacteria were suspended in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 1% brain-heart infusion broth. Bacteria were mixed with the indicated peptide concentrations in a 96-well polypropylene plate (Costar 3790) and incubated for 1 h at 33°C (H. ducreyi) or 37°C (E. coli), and the remaining bacteria were quantified by plate count. Survival in the presence of APs was calculated as a percentage of the rate of survival in control wells without APs. Results were subjected to a mixed-model statistical analysis, and the Sidak adjustment was used to control for multiple comparisons (17). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Differential susceptibilities of H. ducreyi and E. coli to APs.

H. ducreyi is susceptible to killing by PG-1, a porcine AP with no human homolog (8). In our assay, both H. ducreyi and E. coli exhibited <1% survival at a PG-1 concentration of 0.2 μg/ml (data not shown). Thus, our assay detected AP-mediated bactericidal activity.

In assays with α-defensins, E. coli was sensitive to HNP-1 to -3, demonstrating 10 to 30% survival at 20 μg/ml (Fig. 1A to C). HD-5 was more potent against E. coli, with <1% survival at 20 μg/ml and 16% survival at 2 μg/ml (Fig. 1D). In contrast, H. ducreyi exhibited >88% survival at all concentrations of HNP-1 to -3 and HD-5 (Fig. 1) and was significantly more resistant than E. coli to α-defensin-mediated killing.

FIG. 1.

H. ducreyi is significantly more resistant than E. coli to the bactericidal effects of α-defensins. Percent survival of bacteria exposed to α-defensins HNP-1 (A), HNP-2 (B), HNP-3 (C), and HD-5 (D). H. ducreyi 35000HP, black bars; E. coli ML35, gray bars. Data represent the means ± standard errors of the results of three independent assays. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between strains at the indicated concentration of AP, with P < 0.0001 (HNP-1 and HD-5), P = 0.0017 (HNP-2), and P = 0.033 (HNP-3).

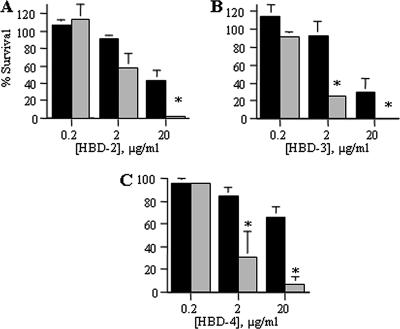

In β-defensin assays, <7% of E. coli survived a peptide concentration of 20 μg/ml that 26 to 66% of H. ducreyi survived (Fig. 2). At a concentration of 2 μg/ml, only 25 to 30% of E. coli but >84% of H. ducreyi survived exposure to HBD-3 and HBD-4 (Fig. 2B and C). At a peptide concentration of 20 μg/ml, which represents 5 μM of α-defensin or 2 to 4 μM of β-defensin, the β-defensins exhibited greater bactericidal activity than the α-defensins against H. ducreyi. Nevertheless, H. ducreyi was significantly more resistant than E. coli to killing by HBD-2 to -4 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

H. ducreyi is significantly more resistant than E. coli to the bactericidal effects of β-defensins. Percent survival of bacteria exposed to β-defensins HBD-2 (A), HBD-3 (B), and HBD-4 (C). H. ducreyi 35000HP, black bars; E. coli ML35, gray bars. Data represent the means ± standard errors of the results of three independent assays. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between strains at the indicated concentration of AP, with P < 0.0001 (HBD-2, HBD-3, and HBD-4 at 20 μg/ml) and P = 0.0089 (HBD-4 at 2 μg/ml).

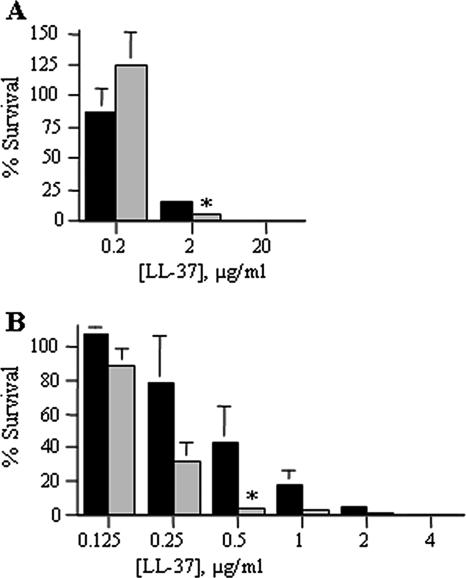

LL-37 exhibited qualitatively greater activity than the defensins against E. coli and H. ducreyi. Nonetheless, the rate of survival of H. ducreyi (16%) was significantly greater than the rate of survival of E. coli (5%) at a dose of 2 μg/ml peptide (Fig. 3A). When LL-37 activity was assessed with serial twofold dilutions, the rate of survival of H. ducreyi (43%) was significantly higher than the rate of survival of E. coli (3%) at a dose of 0.5 μg/ml (Fig. 3B). These data shown that, relative to the level of resistance of E. coli, H. ducreyi resists LL-37 activity.

FIG. 3.

H. ducreyi is significantly more resistant than E. coli to the bactericidal effects of the human cathelicidin LL-37. Percent survival of bacteria exposed to 10-fold (A) and 2-fold (B) serial dilutions of LL-37. H. ducreyi 35000HP, black bars; E. coli ML35, gray bars. Data represent the means ± standard errors of the results of three independent assays. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between strains at the indicated concentration of AP, with P < 0.0001 (A) and P = 0.0012 (B).

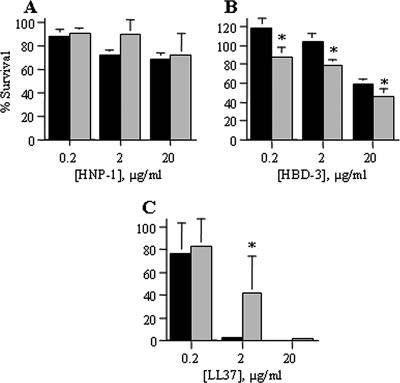

Both H. ducreyi classes are resistant to APs.

H. ducreyi strains comprise two phenotypic classes (20). We compared the susceptibilities of the class I strain 35000HP and the class II strain CIP542 ATCC (8) to PG-1, HNP-1, HBD-3, and LL-37. As with 35000HP, CIP542 ATCC was susceptible to PG-1, with <2% survival at a dose of 0.2 μg/ml (data not shown). 35000HP was significantly more resistant than CIP542 ATCC to HBD-3 but less resistant than CIP542 ATCC to LL-37 (Fig. 4A and B). Importantly, both the class I and class II strain exhibited resistance to all human APs tested (Fig. 4), indicating that AP resistance may represent a conserved mechanism of H. ducreyi survival.

FIG. 4.

Representative class I and class II H. ducreyi strains are both resistant to APs. Susceptibility of class I 35000HP and class II CIP542 ATCC to α-defensin HNP-1 (A), β-defensin HBD-3 (B), and cathelicidin LL-37 (C). Class I results are shown in black, and class II results are shown in gray. Data represent the means ± standard errors of the results of three independent assays. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences between strains at the indicated concentration of AP, with P < 0.02 for HBD-3 and P = 0.0036 for LL-37.

Radial diffusion assays.

Bactericidal assays showed low levels of killing of H. ducreyi with the β-defensins and LL-37 (Fig. 2 and 3). We thus assessed the activities of these APs in a radial diffusion assay (RDA), which enabled the calculation of a minimum effective concentration (MEC) of each peptide against each strain. The RDA was performed as previously described (8) except that salts were omitted from the agarose underlay to prevent the inactivation of salt-sensitive APs. The units of AP activity were derived from measuring the zones of inhibition surrounding AP-impregnated wells. The MEC of each peptide was defined as the x intercept of plots of AP activity over the AP concentration range (Table 1) (8, 18). If less than two concentrations exhibited activity against a strain, no x intercept could be defined, and the MEC was estimated as >158 μg/ml, the upper limit of measurable MEC in this assay.

TABLE 1.

MECs of APsa

| Peptide | E. coli ML35 | H. ducreyi 35000HP | H. ducreyi CIP542 ATCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| PG-1 | 2.5 | 39.0 | 23.1 |

| HBD-2 | 11.1 | >158 | >158 |

| HBD-3 | 17.4 | >158 | >158 |

| HBD-4 | 12.6 | >158 | >158 |

| LL-37 | 6.2 | >158 | >158 |

MEC in μg/ml, calculated as the x intercept of the best-fit line. Data are the mean MECs from three independent assays, each performed in duplicate.

All peptides exhibited activity against E. coli, with MECs between 2 and 18 μg/ml (Table 1). The MECs of PG-1 against the H. ducreyi strains were not significantly different than the PG-1 activity against E. coli (Student's t test; P = 0.1). With LL-37 and the β-defensins, the dose curves from the RDAs showed significantly less activity against either H. ducreyi strain than against E. coli (P < 0.001; data not shown). The MECs of LL-37 and the β-defensins against H. ducreyi exceeded the upper limits of the assay, while the MECs of the human APs against E. coli were <20 μg/ml (Table 1). These data confirm that both known classes of H. ducreyi are significantly more resistant than E. coli to LL-37 and HBD-2 to -4.

Concluding remarks.

We have demonstrated that H. ducreyi is resistant to human APs likely encountered during infection. Control assays confirmed previous studies demonstrating that the organism is susceptible to PG-1, which H. ducreyi does not naturally encounter (8). The differential susceptibility of H. ducreyi to human and animal APs may contribute to both its limited host range (humans) and differences in the organism's survival in human and animal models of infection (16, 19), although a much broader panel of APs tested against more H. ducreyi strains is needed to address this hypothesis.

Pathogens have evolved various mechanisms to overcome bactericidal APs, including modulating AP production, inactivating APs, pumping APs out of the cell or into the cytoplasm, and repelling APs electrostatically (6, 11, 13). The expression of multiple AP-resistance strategies in pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Salmonella enterica, and Staphylococcus aureus demonstrates the importance to pathogenesis of combating APs. Future work will focus on elucidating the mechanism(s) of AP resistance in H. ducreyi.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert I. Lehrer for providing PG-1 and helpful discussions; Stanley M. Spinola for the H. ducreyi strains; Anna Pulliam, Linden Horton, and Ashley Alexander for technical assistance; and Susan Ofner for statistical support. We thank Stanley M. Spinola and X. Frank Yang for helpful discussions and critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Developmental Awards Program of the National Institutes of Health NIAID Sexually Transmitted Infections and Topical Microbicide Cooperative Research Centers (STI-TM CRC) grants to the University of Washington (AI 31448) and Indiana University (AI 31494) and by the Indiana Genomics Initiative of Indiana University, which is supported in part by Lilly Endowment, Inc.

All authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agerberth, B., J. Charo, J. Werr, B. Olsson, F. Idali, L. Lindbom, R. Kiessling, H. Jörnvall, H. Wigzell, and G. H. Gudmundsson. 2000. The human antimicrobial and chemotactic peptides LL-37 and α-defensins are expressed by specific lymphocyte and monocyte populations. Blood 96:3086-3093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq, J. A., A. C. Thornton, B. P. Katz, K. R. Fortney, K. D. Todd, A. F. Hood, and S. M. Spinola. 1998. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1684-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer, M. E., M. P. Goheen, C. A. Townsend, and S. M. Spinola. 2001. Haemophilus ducreyi associates with phagocytes, collagen, and fibrin and remains extracellular throughout infection of human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:2549-2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer, M. E., and S. M. Spinola. 2000. Localization of Haemophilus ducreyi at the pustular stage of disease in the human model of infection. Infect. Immun. 68:2309-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, M. E., C. A. Townsend, A. R. Ronald, and S. M. Spinola. 2006. Localization of Haemophilus ducreyi in naturally acquired chancroidal ulcers. Microb. Infect. 8:2465-2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman, P., L. Johansson, V. Asp, L. Plant, G. H. Gudmundsson, A.-B. Jonsson, and B. Agerberth. 2005. Neisseria gonorrhoeae downregulates expression of the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Cell. Microbiol. 7:1009-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faurschou, M., O. E. Sörensen, A. H. Johnsen, J. Askaa, and N. Borregaard. 2002. Defensin-rich granules of human neutrophils: characterization of secretory properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1591:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortney, K., P. Totten, R. Lehrer, and S. Spinola. 1998. Haemophilus ducreyi is susceptible to protegrin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2690-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulton, C., G. M. Anderson, M. Zasloff, R. Bull, and A. G. Quinn. 1997. Expression of natural peptide antibiotics in human skin. Lancet 350:1750-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenssen, H., P. Hamill, and R. E. Hancock. 2006. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:491-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraus, D., and A. Peschel. 2006. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial resistance to anticmicrobial peptides. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 306:231-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehrer, R. I., A. Barton, K. A. Daher, S. S. L. Harwig, T. Ganz, and M. E. Selsted. 1989. Interaction of human defensins with Escherichia coli: mechanism of bactericidal activity. J. Clin. Investig. 84:553-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason, K. M., M. E. Bruggeman, R. S. Munson, Jr., and L. O. Bakaletz. 2006. The non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae Sap transporter provides a mechanism of antimicrobial peptide resistance and SapD-dependent potassium acquisition. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1357-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter, E., H. Yang, S. Yavagal, G. C. Preza, O. Murillo, H. Lima, S. Greene, L. Mahoozi, M. Klein-Patel, G. Giamond, S. Gulati, T. Ganz, P. A. Rice, and A. J. Quayle. 2005. Distinct defensin profiles in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis reveal novel epithelial cell-neutrophil interactions. Infect. Immun. 73:4823-4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quayle, A. J., E. M. Porter, A. A. Nussbaum, Y. M. Wang, C. Brabee, K. P. Yip, and S. C. Mok. 1998. Gene expression, immunolocalization, and secretion of human defensin-5 in human female reproductive tract. Am. J. Pathol. 152:1247-1258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.San Mateo, L. R., K. L. Toffer, P. E. Orndorff, and T. H. Kawula. 1999. Neutropenia restores virulence to an attenuated Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient Haemophilus ducreyi strain in the swine model of chancroid. Infect. Immun. 67:5345-5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sidak, Z. 1967. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 62:626-633. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starner, T. D., W. E. Swords, M. A. Apicella, and P. B. McCray, Jr. 2002. Susceptibility of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to human β-defensins is influenced by lipooligosaccharide acylation. Infect. Immun. 70:5287-5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Throm, R. E., and S. M. Spinola. 2001. Transcription of candidate virulence genes of Haemophilus ducreyi during infection of human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:1483-1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White, C. D., I. Leduc, B. Olsen, C. Jeter, C. Harris, and C. Elkins. 2005. Haemophilus ducreyi outer membrane determinants, including DsrA, define two clonal populations. Infect. Immun. 73:2387-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, D., A. Biragyn, D. M. Hoover, J. Lubkowski, and J. J. Oppenheim. 2004. Multiple roles of antimicrobial defensins, cathelicidins, and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin in host defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:181-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]