Abstract

The combination of high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging and single-molecule force-spectroscopy was employed to unfold single bacteriorhodopsins (BR) from native purple membrane patches at various physiologically relevant temperatures. The unfolding spectra reveal detailed insight into the stability of individual structural elements of BR against mechanical unfolding. Intermittent states in the unfolding process are associated with the stepwise unfolding of α-helices, whereas other states are associated with the unfolding of polypeptide loops connecting the α-helices. It was found that the unfolding forces of the secondary structures considerably decreased upon increasing the temperature from 8 to 52°C. Associated with this effect, the probability of individual unfolding pathways of BR was significantly influenced by the temperature. At lower temperatures, transmembrane α-helices and extracellular polypeptide loops exhibited sufficient stability to individually establish potential barriers against unfolding, whereas they predominantly unfolded collectively at elevated temperatures. This suggests that increasing the temperature decreases the mechanical stability of secondary structural elements and changes molecular interactions between secondary structures, thereby forcing them to act as grouped structures.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy/molecular interactions/purple membrane/secondary structure/structural stability

Introduction

Molecular forces interacting between and within biological macromolecules determine biomolecular structures, their dynamics and their functions (Haltia and Freire, 1995; White and Wimley, 1999; Popot and Engelman, 2000). But how do these forces stabilize secondary structure elements, how do they mediate interactions between these structures, and how do these forces depend on environmental conditions within physiological relevant ranges? Currently, molecular interactions are typically inferred indirectly from equilibrium binding and kinetic measurements or are calculated using molecular models. Recent perceptions of protein (un)folding, such as described by multidimensional landscapes or folding funnels, can be seen as a result of the complexity of inter- and intramolecular interactions (Radford, 2000). Different (un)folding pathways may be populated in dependence of small alterations of the physiological environment, which challenges novel approaches, to observe co-existing minor and major pathways on single molecules.

With the recent developments of single-molecule force-spectroscopy, such inter- and intramolecular interactions of biological macromolecules became directly accessible (Fisher et al., 1999; Rief et al., 2000). In single-molecule force-spectroscopy, the two ends of a molecule are tethered to the tip of a cantilever and to a solid support, respectively, while the cantilever deflection is monitored with high accuracy of ≈0.1 nm upon elongation. A characteristic force distance curve for this molecule is obtained by recording the cantilever deflection against the tip-support separation. Single-molecule force-spectroscopy has been applied to measure biological interactions such as forces that mediate molecular recognition (Lee et al., 1994; Moy et al., 1994; Fritz et al., 1998), stabilize molecular structures (Fisher et al., 1999; Rief et al., 2000), drive intermolecular interactions (Dammer et al., 1996), form molecular bonds (Grandbois et al., 1999; Merkel et al., 1999) and molecular elasticities (Kellermayer et al., 1997; Rief et al., 1998a; Bustamante et al., 2000; Clausen-Schaumann et al., 2000). Constructs of modular proteins were unfolded mechanically and revealed for the first time a direct correlation between folding pattern and mechanical function (Oberhauser et al., 1999; Rief et al., 2000). Models were developed that allow a theoretical description of the molecular compliances based on the combination of established polymer models in combination with discrete unfolding events (Rief et al., 1998a; Zhang et al., 1999). Forced unfolding experiments performed on fibronectin (Rief et al., 1998b), tenascin (Oberhauser et al., 1998), and titin (Oberhauser et al., 1999; Rief et al., 2000), showed that these modular proteins unfold domain after domain preferentially in an only all or none event with no intermediate states. Only in rare cases, intermittent steps have been reported (Marszalek et al., 1999). Interestingly, single-molecule spectroscopy experiments recently demonstrated titin and fibronectin domains of tenascin to unfold at different forces, although their thermal stability was shown to be identical using differential scanning calorimetry (Rief et al., 1998b). This latter example indicates that force-spectroscopy can be used to reveal interactions that contribute to the structural stability of proteins, which are not accessible by thermal denaturation.

An additional principal difference between mechanical single molecule experiments and conventional unfolding experiments by thermal or chemical denaturation should be pointed out: conventional experiments deal with high densities of proteins immersed in solutions. Consequently, possible influences between the densely packed molecules are to be suppressed and the challenge is to dilute the solution as far as possible to ensure that the unfolded proteins do not interact with each other. However, sample dilution is limited by the finite sensitivity of the detection method (Booth et al., 2001). In single-molecule force-spectroscopy, however, a single protein is surrounded by quasi infinite solution.

In contrast to most unfolding experiments on globular proteins, the combination of single-molecule imaging and force-spectroscopy on the membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin (BR) yielded surprisingly detailed insights into inter- and intramolecular interactions. It has been shown that structural elements of BR unfold sequentially, making the assignment of certain features of the measured force spectra to the corresponding amino acid (aa) sequence possible. The consequent analysis provided comprehensive information on structural properties of individual BR molecules within the native purple membrane from the halophilic archaeon Halobacterium salinarum (Oesterhelt et al., 2000). Interactions that stabilize individual structural elements of BR, such as transmembrane α-helices and polypeptide loops were detected (Müller et al., 2002). In this study, we characterize the influence of temperature on the mechanical stability of BR by combining high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging and single-molecule force-spectroscopy. BR was unfolded at temperatures from 8 to 52°C, the latter being comparable to the physiologically relevant temperature of the halophilic bacteria. The data show that the unfolding forces decrease significantly with increasing temperature while the probability of pairwise unfolding of transmembrane α-helices increases significantly.

The light-driven proton pump BR was chosen as a model system for this study because it represents one of the most extensively studied membrane proteins (Oesterhelt, 1998; Haupts et al., 1999). Together with adjacent lipids, BR molecules assemble into trimers, which are packed into the two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of purple membrane as a chemically distinct domain of the cell membrane. BR converts the energy of light (λ = 500–650 nm) into an electrochemical proton gradient, which in turn is used for ATP production by ATP-synthases. Structural analysis of BR has revealed that the photoactive retinal is embedded in seven closely packed transmembrane α-helices (Lanyi, 1999; Subramaniam, 1999), which builds a common structural motif among a large class of related G protein-coupled receptors (Helmreich and Hofmann, 1996). The BR helices are designated as helices A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, to which the C-terminal end is connected. With increasing knowledge of its structural and functional properties, BR has become a paradigm for α-helical membrane proteins in general and for ion transporters in particular (Lanyi, 1999; Subramaniam, 1999).

Results

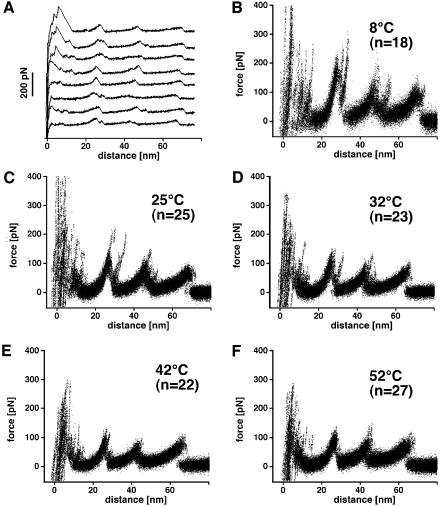

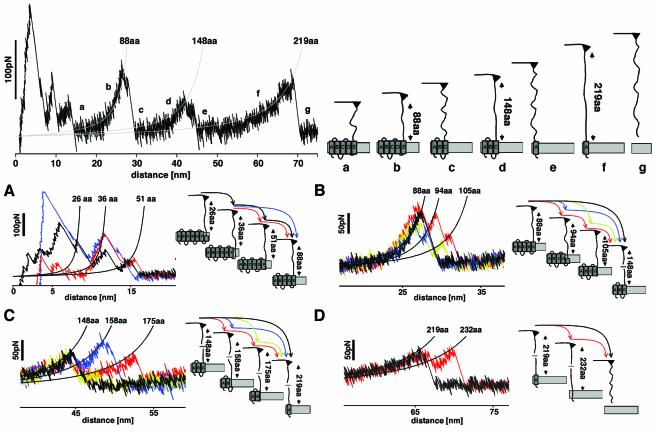

Figure 1A shows a selection of force-extension traces recorded on single BR molecules. An interpretation of a typical trace exhibiting common features observed among all curves is given at the top of Figure 2. After separating AFM tip and purple membrane, the C-terminal polypeptide of BR is extended. Further separating tip and membrane stretches the C-terminal end and the force builds up in a gradual but non-linear fashion. At a certain force, the first transmembrane helices G and F unfold. This increases the length of the molecular bridge between tip and membrane, the cantilever relaxes and the force drops abruptly. By further separation of the AFM tip and membrane surface, the polypeptide chain of the unfolded structural elements extends. As soon as the polypeptide is stretched again, the force rises (as detected by the cantilever deflection). At a certain force, the next (in terms of the polypeptide chain) secondary element of BR unfolds. The gradual, non-linear force increase of the extension traces can be well fitted with the wormlike chain (WLC) model with only one free parameter: the contour length of the stretched portion of the molecule. This fit describes the increasing slopes of the traces at low forces, with each peak of the discontinuous force spectrum marking the position of a potential barrier of the BR molecule. As shown previously, the fitted contour length of the force-extension curve and the secondary structure model of BR suggest that helices G and F, D and E, and B and C unfold pairwise (Oesterhelt et al., 2000). The remaining seventh helix, A, is then pulled from the membrane in a single step. Beyond an extension of 70 nm no interaction is measured.

Fig. 1. Unfolding BR from native purple membrane at various temperatures. (A) Force curves of individual BR molecules recorded at 25°C. To show common unfolding patterns among single-molecule events, the force spectra recorded at different temperatures were superimposed. (B–F) BR unfolded at 8°C (B), 25°C (C), 32°C (D), 42°C (E) and 52°C (F) in 300 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl with a pH of 7.8 being adjusted for each temperature.

Fig. 2. Unfolding pathways of BR. Top, pairwise unfolding pathways of transmembrane α-helices. The left curve shows a representative unfolding spectrum of a single BR, while the schematic drawing of the unfolding pathways is shown on the right. The first force peaks detected within a separation of 0–15 nm to the purple membrane surface indicate the unfolding of transmembrane α-helices F and G, and of loops FG and EF. The first peaks within this region are superimposed by non-specific surface interactions between purple membrane and AFM tip. After the unfolding event (a), the amount of aa stretched is increased to 88 and the cantilever relaxes. Further separating tip and sample stretches the polypeptide (b) thereby pulling on helix E. At a certain pulling force, the mechanical stability of helices E and D is insufficient and they unfold together with loops DE and CD (c). The available 148 aa are now stretched (d), the polypeptide being pulling on helix C. Helices B and C and loops BC and AB unfold within a single step, thereby relaxing the cantilever (e). By further separating tip and purple membrane, the cantilever pulls on helix A (f) until the polypeptide is completely extracted from the membrane (g). The force-spectroscopy curve was recorded in 300 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.8 at room temperature. (A–D) Unfolding events of individual secondary structures. (A) Occasionally the first major unfolding peak shows side peaks at about 26, 36 and 51 aa. The peak at 26 aa indicates the unfolding of the cytoplasmic half of α-helix G up to the covalently bound retinal, which is embedded in the hydrophobic membrane core. The peak at 36 aa indicates the G helix to be unfolded completely. At 51 aa, helix G and the loop connecting helices G and F are unfolded and the force pulls directly on helix F until this helix unfolds together with loop EF. (B) The side peaks of the second major peak indicate the stepwise unfolding of helices E and D and loop DE. The peak at 88 aa indicates the unfolding of helix E, that at 94 aa of the loop DE, and the peak at 105 aa indicates unfolding of helix D. (C) The side peaks of the third major peak indicate the stepwise unfolding of helices C and B and loop BC. The peak at 148 aa indicates the unfolding of helix C, that at 158 aa of the loop BC, and the peak at 175 aa indicates unfolding of helix B. (D) The side peak of the last major peak indicates the unfolding of helix A (219 aa) and of the pulling of the N-terminal end through the purple membrane (232 aa).

In those cases where the main force peak drops without further (often smaller) force peaks being detected (Figure 2B,C and D, black arrows), the grouped structural elements unfold within a single step. Occasionally, a main force peak drops to zero with further (smaller) force peaks. In a previous study, these side peaks were identified as unfolding events of single secondary structure elements such as transmembrane α-helices and polypeptide loops (Müller et al., 2002). The assignment of the observed force peaks to the unfolding events of individual structural elements is given in Figure 2A–D.

To see to what extent these unfolding events of secondary structural elements depend on the temperature, force extension curves were recorded at 8°C (Figure 1B), room temperature (25°C; Figure 1C), 32°C (Figure 1D), 42°C (Figure 1E), and 52°C (Figure 1F). Each graph shows a multitude of force extension traces, each one recorded on one single BR (such as shown in Figure 1A). In these figures, ∼25 traces are superimposed. This kind of graphic representation highlights common features through the accumulation of the measured points and at the same time still represents the individualism of traces. Independent of the temperature adjustment, each curve exhibited a richness of detailed information on the mechanics of this molecule. It becomes clear that the main peaks at 27, 45 and 65 nm remain at their position (Figure 1), but that the rupture forces of these unfolding events decrease with increasing temperature (Figure 3). The steepest decrease of the rupture forces was observed between 8 and 32°C. Above 32°C, the rupture force decreased only slightly, showing a fluctuation of a similar range as the standard deviation of the mean value.

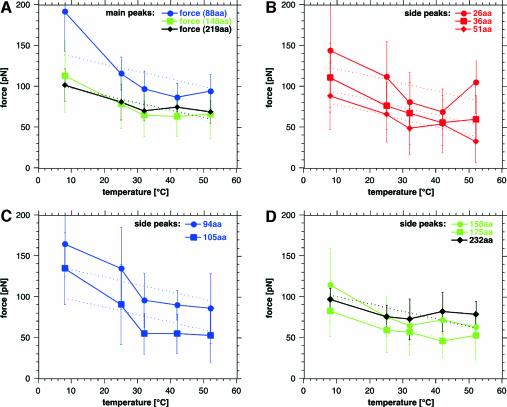

Fig. 3. Unfolding forces of secondary structural elements depend on temperature. (A) Rupture forces of main peaks, which exhibited no side peaks. The forces represent the pairwise unfolding of transmembrane α-helices E and D (88 aa), C and B (148 aa) and the unfolding of helix A (219 aa). The main peak representing the pairwise unfolding of helices G and F are not shown because unspecific surface interactions between the AFM tip and the purple membrane scatter the position and appearance of the force peaks significantly. (B–D) Rupture forces of side peaks represent unfolding of single α-helices and of their connecting loops (see text). The thermally induced weakening of the unfolding forces was fitted (dotted lines) using equation (2).

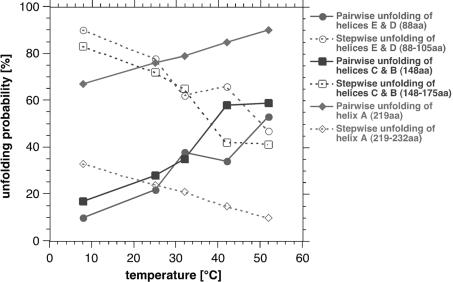

Similarly to the main peaks, the side peaks did not change their position (contour length) upon variation of the temperature. To see whether the rupture force (Figure 3) or the probability (Figure 4) of the side peaks change with temperature, they were analyzed from each single force-extension curve. Interestingly, the average rupture force of all side peaks decreased with increasing temperature (Figure 3). However, the frequency of the side peaks decreased with increasing temperature (Figure 4). Accordingly, the frequency of the main peaks increased with the temperature (Figure 4). This indicates that the pairwise unfolding of transmembrane α-helices is favored with increasing temperature, while with decreasing temperature, the unfolding probability of single secondary structure elements, such as helices and loops, is enhanced.

Fig. 4. Probability of unfolding pathways depends on temperature. The occurrence of main force peaks exhibiting no side peaks (solid lines) increased with increasing temperature. As a consequence, the probability of the main peaks exhibiting side peaks (dashed lines) decreased significantly. Solid lines represent probabilities for the pairwise unfolding of transmembrane α-helices E and D (88 aa, red), C and B (148 aa, blue) and of helix A (219 aa, green). The probability of their stepwise unfolding is presented by the dotted lines. This indicates α-helices of BR unfold preferentially pairwise at elevated temperatures. The probability of single structural elements, such as helices or loops, to unfold in a separate event decreases with increasing temperature.

Discussion

Stabilization and unfolding of transmembrane α-helices

In our measurements, the forces required to unfold single α-helices of BR from native purple membrane are measured directly. Our observations support the concept of independently stable transmembrane helices to be a key feature of their assembly into a higher-ordered structure (Popot and Engelman, 2000). In this so-called two-stage model, the sequential folding of BR is explained. First, individual helices are inserted as separate stable fragments into the membrane. After this, the helices assemble into the functional protein. It is suggested that the BR fragments act like domains of soluble proteins. Together with their connecting loops the transmembrane helices assume a free energy minimum, found by the characteristic tertiary structure. As our single-molecule force-spectroscopy measurements have shown, each of these individual structural elements exhibits an energy minimum, establishing an internal potential barrier against mechanical unfolding. Although the BR helices exhibit sufficient stability to unfold in a single step, at the same time they exhibit a distinct probability to unfold pairwise. This observation proposes that a pairwise association drives transmembrane helices into a conformation of comparable mechanical stability as that observed for single helices.

Spontaneous unfolding of α-helices

The data suggest hydrophobic structural elements of BR (transmembrane α-helices) to be extracted from, or hydrophilic structures (extracellular polypeptides) to be pulled through, the hydrophobic membrane at reduced forces if the temperature is increased. The main peaks of the force spectra, however, cannot distinguish whether the secondary structures of BR are initially extracted from the membrane followed by an unfolding process outside the hydrophobic membrane core, or whether the helices unfold spontaneously as soon as the externally applied force supersedes their mechanical stability. Occasionally, the main unfolding peaks exhibit side peaks, indicating that single helices and loops unfold individually (Figure 2). Interestingly, the unfolding spectra of helices E (Figure 2B, red and blue pathways), C (Figure 2C, red and blue pathways) and A (Figure 2D, red pathway) suggest that they remain stably embedded in the membrane until they are spontaneously unfolded in a single event. Otherwise, the directly connected extracellular polypeptide loops could not remain folded and located at their position. Premature unfolding of such a loop would not allow detection of its discrete unfolding peak in a subsequent event and would extend the total length of the stretched polypeptide of the helix unfolded directly before. As a result, the force peaks of helices D and B would be shifted by the length of their stretched extracellular loop. Similarly, in the case of unfolding helix A, the force peak detected at 232 aa (Figure 2D) would not have been detected.

Unfolding structural motifs

As detected directly by the unfolding spectra and as suggested by Popot and Engelman (Popot et al., 1987; Popot and Engelman, 2000), a structural motif of BR is built by two transmembrane helices and their connecting polypeptide loop. If pulled from the C-terminal end, the second helix of this structural motif unfolds at smaller forces compared with the first helix. Most probably, this effect results from the destabilization of the structural motif by the unfolding process. The individualism of their unfolding pathways emerged as a very prominent feature throughout the study. Whether or not this individualism of the pathways reflects the individualism of the protein, rather than fluctuations at bifurcation points in the unfolding trajectories, remains to be elucidated in further studies. Although we have measured the positions of the different unfolding barriers quite precisely, we have not yet identified their underlying mechanisms. Particularly, our finding that the extracellular loops resist unfolding at an external force comparable with the force required to unfold a transmembrane α-helix, calls for additional future investigations.

BR structure remains mainly unchanged within the temperature range investigated

Using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (Cladera et al., 1992; Taneva et al., 1995), X-ray diffraction (Shen et al., 1993; Koltover et al., 1999; Müller et al., 2000) and circular dichroism (Brouillette et al., 1987; Shnyrov and Mateo, 1993), it was shown that the intramembranous parts of BR do not undergo significant structural changes within the temperature range studied here. This is further supported by the proton pumping activity of BR, which is maintained (Racker and Hinkle, 1974), and the observation that no intramembranous elements become exposed to papain digestion (Brouillette et al., 1987) at these temperatures. These findings suggest that BR fully maintains its native function, and that internal structural changes would be minimal within the temperature range studied here.

Temperature-dependent destabilization of transmembrane α-helices

The subset of force curves recorded at temperatures ranging from 8 to 52°C show the individual unfolding pathways of BR, such as previously detected at room temperature (22°C; Müller et al., 2002). A common feature of all measurements is that the average force detected for each unfolding event decreases upon increasing the temperature. Apparently, this observation contrasts with the suggestion that the thermal influences on the BR structure are negligible within the temperature range studied here. However, force-spectroscopy detects the stability of a protein and not necessarily its structural changes. Thus, it appears interesting that, although the BR structure remains unchanged, the interactions stabilizing the structure were strongly affected by temperature variations within a physiologically relevant range.

The potential barriers detected in the force spectra can be assigned to secondary structural elements (Müller et al., 2002), which are stabilized by inter- and intramolecular interactions (Haltia and Freire, 1995; White and Wimley, 1999; Popot and Engelman, 2000). The intermolecular forces involve interactions of the protein with surrounding lipids and neighboring proteins. An important contribution to the intermolecular forces is formed by hydrophobic interactions, which anchor and stabilize a membrane protein within the lipid bilayer. In model experiments, this hydrophobic interaction is frequently manipulated to adjust the solubility of membrane proteins or to favor the reconstitution of membrane proteins into a lipid bilayer (Kühlbrandt, 1992; Hasler et al., 1998). From experiments measuring the solubility of hydrophobic molecules in aqueous solution, it can be concluded that the hydro phobic interaction increases with increasing temperature (Tanford, 1980). Other important contributions to the forces stabilizing proteins result from intramolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding and electrostatic and van der Waals interactions.

Structural transitions of lipids may influence membrane protein stability

In this study, the most drastic decreases of unfolding force were detected with an increase in temperature from 8 to 32°C. Within this range, experimental results obtained by differential scanning calorimetry suggested purple membrane undergoes thermal transitions (Chignell and Chignell, 1975), which are potentially associated with lipid rearrangements (Wilkinson and Nagle, 1982; Blume, 1983; Tristram-Nagle et al., 1986). There has been confusion about the discrepancy with other results that report no transition of purple membrane within this temperature range (Jackson and Sturtevant, 1978). Apparently, the observation of this thermal transition depends on purple membrane concentration, which must be sufficient to detect specific heats of the lipids by calorimetry (Tristram-Nagle et al., 1986). Such structural rearrangements of lipids, however, change the interactions between lipids as well as interactions with the membrane protein (Tristram-Nagle et al., 1986; Nishiya et al., 1987; Haltia and Freire, 1995). Thus, it may be concluded that the significant reduction of unfolding forces measured here is a result of lipid transitions occurring within the temperature range of 8–32°C.

Another aspect of the steep rupture force decrease observed between 8 and 32°C is the fact that for helices D and E the unfolding forces decrease by about 80 pN while for all other peaks a change of 30 pN is not exceeded. The space occupied by two helices equals the volume of about nine lipid molecules, corresponding to a membrane area of four and a half lipid molecules. This compares with five lipid molecules per BR in one purple membrane leaflet (Luecke et al., 1998). Thus, removal of the first four helices, G, F, E and D, creates a considerable hole, which exposes the lipids to a different environment compared with those lipids that are structurally constrained within the intact protein crystal. Creation of more space and environmental changes might facilitate large structural transitions of the surrounding lipids (Israelachvili, 1991). After such structural rearrangements, the lipids surrounding the hole may not behave as those observed in native purple membrane. This may explain why we do not observe a similarly steep temperature-dependent decrease of the unfolding force for helices that have been extracted after a considerable hole has been created. Therefore, it may be assumed that the temperature-dependent decrease of rupture force revealed for those helices that have been unfolded after the first ones, might reflect their intrinsic interactions rather than those associated with lipid transitions within the membrane (see also Theoretical considerations).

From 32 to 52°C, the unfolding forces of transmembrane α-helices show a weak dependence on the temperature. While the force to unfold α-helices pairwise remains mainly unaffected by the temperature increase, the unfolding force of single helices decreases slightly [Figure 3, helix F (51 aa), helix D (105 aa), helix B (175 aa) and helix A (219 aa)]. This reduction of the potential barriers of the secondary structures is in apparent contrast with the hydrophobic interaction, which increases with the temperature and anchors transmembrane helices in the membrane (Tanford, 1980; Haltia and Freire, 1995; White and Wimley, 1999; Popot and Engelman, 2000). Thus, it may be suggested that the temperature induces a thermal destabilization of secondary structural elements, which becomes, at this stage, more dominant than possible hydrophobic contributions.

Unfolding polypeptide loops

The force peaks assigned to potential barriers against the mechanical pulling of the polypeptide loops, decreased with increasing temperature. Since hydrophilic loops connecting the transmembrane α-helices are located outside of the purple membrane, it may be concluded that a temperature increase may significantly destabilize the loop structure. However, unfolding of an extracellular loop structure by mechanical pulling of the polypeptide from the cytoplasmic side is directly followed by or associated with a physical transport of the hydrophilic aa residues through the hydrophobic membrane interior. This hydrophobic interaction, which prevents hydrophilic molecules from penetrating through a membrane bilayer, increases with the temperature (Tanford, 1980). Naturally, conformational changes of the loop structure and its transport through the membrane bilayer require contributions of external energy or force, such as applied mechanically in the experiments. From the current understanding of the hydrophobic interaction, one would expect that the force required to transport a hydrophilic peptide through a hydrophobic core increases with the temperature. Thus, our measurements suggest that an individual force peak of a polypeptide loop reflects its structural stability rather than the force required to transport their hydrophilic aa through the membrane. The observed specific ordering of these loops, which was observed in high-resolution structures of BR (Belrhali et al., 1999; Luecke et al., 1999), may further support this hypothesis. Detailed insights into which contributions of the adhesion force measured result from the unfolding of an extracellular polypeptide loop and which result from the physical transport of the loop through the membrane, may be gained with force microscopes that allow higher force and temporal resolution.

Temperature-dependent unfolding pathways of BR

At increased temperatures, the unfolding force of every structural element of BR decreased, indicating that their potential barriers, built up against mechanical unfolding, were lowered. The temperature variation did not influence the appearance of the unfolding pathways. This means, every individual pathway was observed at each of the temperatures adjusted. However, the probability of a BR molecule choosing a certain unfolding pathway was found to depend on the temperature. Whereas the probability of pairwise unfolding of transmembrane α-helices increased significantly with the temperature, the unfolding probabilities of single helices and of helical segments decreased. Similarly, the probability of the hydrophilic polypeptide loops to unfold individually decreased with increasing temperature (Figure 4). Obviously, at elevated temperatures, the potential barrier for unfolding two helices versus that of unfolding a single one decreases and groups of secondary structure elements predominantly unfold in a single step. This observation opens new questions about the molecular mechanisms that may change the unfolding pathways. Currently, one may take two possibilities into account: potential barriers of individual structural elements may simply change their height and position thereby shifting their probability for certain unfolding pathways; alternatively, one may assume the potential barrier of a side peak to reduce its height in a way that the barrier is not detected by the cantilever used in this work (Heymann and Grubmüller, 2000). To gain insight into this question, we are currently unfolding BR using cantilevers of different force constants and resonance frequencies.

Theoretical considerations: effects contributing to secondary structure stability

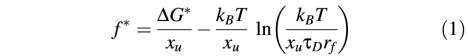

The secondary structure elements of BR establish various potential barriers against mechanical unfolding. From a kinetic point of view, the forced transition from one unfolding barrier to the next can be described as a thermally activated, first-order process. In a pioneering work in 1978, Bell found that an externally applied force reduces the potential barrier such that it can be superseded by thermal fluctuations within the timescale of the experiment (Bell, 1978). A more complete picture of the kinetics of bond dissociation can be revealed from Kramers’ model of thermally assisted barrier crossing in liquids (Kramers, 1940; Hanggi et al., 1990). Here, we apply a modified version of this model, which allows estimation of the extent of temperature-induced kinetic contributions on the most probable unbinding force f* (Evans, 1998):

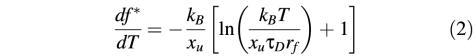

where ΔG* is the height of the energy barrier of activation, xu the distance from the folded state to the transition state representing the potential barrier width, kB the Boltzmann constant, T the temperature, τD the characteristic diffusion time of motion in the system, and rf the loading rate (Evans, 1998). Based on the assumption that the free energy of activation is not temperature dependent, only the second term depends on the temperature. Thus, the slope in a force versus temperature plot is represented by the derivative of this term with respect to the temperature:

Using this formula, we fitted our experimental data (Figure 3) by inserting a potential width of 0.3 nm (see below), a loading rate of ≈1 nN/s (rf in our experiments ranged from 600 to 3000 pN/s) was determined according to Dettmann et al. (2000), and a diffusion time of 10–10 s was used as suggested by Evans (1998). The potential width of 0.3 nm was determined by two independent approaches: first, we fitted the decrease of the unfolding force over the entire temperature range for unfolding peaks observed at 148 aa (Figure 3A), 158 aa (Figure 3D), 175 aa (Figure 3D) and 219 aa (Figure 3A). We selected these peaks since it can be assumed that contributions to their unfolding forces by structural transitions of lipids are minimal (see Discussion), and that only kinetic effects contributed to their thermal destabilization. The peaks were fitted by applying equation (2), revealing values of xu lying within the range from 0.25 to 0.4 nm. Secondly, dynamic force pulling experiments on BR revealed the same potential width of ≈0.3 nm detected for all secondary structure elements of BR (H.Janovjak, J.Struckmeier, M.Kessler, H.E.Gaub and D.J.Müller, manuscript in preparation). Therefore, we used 0.3 nm as estimate for all fits.

In most cases, the calculated values are in good agreement with the experimental data, lying within their standard deviations (Figure 3, dotted lines). As expected from above discussions on the temperature-dependent phase transition of the lipids, maximal deviations were observed in the temperature regime from 8 to 32°C. Since the structural transitions of lipids due to removal of transmembrane helices were only maximal after extraction of the first helices (see above), smaller deviations of the experimental data from the calculated values were observed for the structural elements that were directly extracted after the main peak at 88 aa and side peaks at 94 and 105 aa. Taking these explanations into account, it may be concluded that kinetic weakening dominated the thermal destabilization of these potential barriers. However, from the force shift of each fit it may be assumed that additional constant factors contribute to the unfolding of each secondary structure. From equation (1) it can be assumed that this shift may be due to different energetic contributions stabilizing individual helices and polypeptide loops.

A multidimensional unfolding landscape?

In previous studies, we and others have shown that unfolding forces are rate dependent and that additional information on the geometry of the potential barriers may be extracted from the unfolding traces by varying the pulling speed (Rief et al., 1998a; Merkel et al., 1999). From above results, we assume that different velocities may also influence the probability of the BR unfolding pathways. Since all external parameters, such as pulling speed, temperature, electrolyte and pH are freely adjustable in the experiments shown, it is expected that the knowledge of their influence on the structural stability of proteins will provide a wealth of new insights towards understanding factors and parameters that drive molecular interactions in proteins under physiological relevant conditions. It will be challenging to exploit these effects and to determine all the parameters that influence the unfolding pathways together to reveal a multidimensional unfolding landscape of a protein.

Concluding remarks

Every secondary structural element of BR exhibits a certain intrinsic stability, which appears to be sufficient to regard single transmembrane α-helices and polypeptide loops as stable structures. As a result, the structural elements build up an internal potential barrier against extraction and mechanical unfolding. Mechanical pulling on the cytoplasmic terminus of BR is followed by the extraction and unfolding of its secondary structural elements from purple membrane. These observations strongly support the two-stage model of membrane protein folding. Temperature enhancement of the physiological environment lowers these potential barriers, which is directly reflected in the force peaks of the unfolding spectra. It is concluded that this temperature-dependent phenomena may be attributed to two effects: a thermal transition of purple membrane influencing the lipid–protein interaction, and the thermal destabilization of BR. Most interestingly, each secondary structure element of BR was observed to choose individual unfolding pathways. Their intrinsic probability, to unfold in a separate event or collectively with other structural elements, depends critically on the physiologically relevant temperature of the environment. The collective unfolding process of two transmembrane helices and of their connecting loop became dominant at elevated temperatures, suggesting interactions between helices to dominate the unfolding process.

Materials and methods

Purple membrane preparation

Wild-type purple membrane was extracted from H.salinarum as described previously (Oesterhelt and Stoeckenius, 1974) and adsorbed onto freshly cleaved mica in buffer solution (Müller et al., 1997). All buffer solutions were prepared with nanopure water, and the pH was adjusted using an electrode pH-Meter with a built-in temperature sensor (ΔpH < 0.01, ΔT = 0.3°K; pH-Meter 766 calimatic, Knick, Berlin, Germany). Chemicals utilized were purchased from Sigma/Merck and were p.a. grade.

Attachment of BR to the AFM tip

In previous studies, two different strategies have been developed in order to attach the protein to the tip. We have shown that the cysteine of the G241C mutant binds with a likelihood of 90% to a gold-coated cantilever (Oesterhelt et al., 2000) when the tip is brought into contact with the cytoplasmic purple membrane surface, even at forces below 200 pN. This procedure allows a highly efficient and defined attachment. However, it requires the AFM tip to be replaced after a few experiments since it is covered with bound proteins. An alternative method, the non-specific attachment in combination with subsequent imaging and force trace classification, was shown to provide equivalent results and allows a much higher throughput (Müller et al., 2002). Since this study is a systematic investigation, we chose the non-specific attachment in combination with AFM imaging as described below.

Single-molecule force-spectroscopy and imaging

The contact mode AFM (Nanoscope E, Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) used was equipped with a 100 µm piezo scanner. The spring constants k of the 200 µm long Si3N4 AFM cantilevers (Digital Instruments) were calibrated in solution using the equipartition theorem (Butt et al., 1995; Florin et al., 1995). Within the uncertainty of this method (≈10%) all cantilevers used exhibited the same constant, k = 0.06 N/m. All experiments were performed in buffer solution. To perform force-spectroscopy experiments on BR we recorded high-resolution AFM topographs of the cytoplasmic purple membrane surface as described previously (Oesterhelt et al., 2000). To adsorb the C-terminal end of BR to the AFM stylus, both surfaces were kept in contact for about 1 s while applying a force of 0.5–1 nN. Stylus and protein surface were then separated at a velocity of 87 nm/s while recording the force spectrum. In about 15% of all retraction curves we detected one or more adhesive peaks. About 30% of these retraction curves showed a force extension curve exhibiting a length between 60 and 70 nm (see Data analysis). After detecting one discontinuous force curve, the same area of the protein surface was re-imaged. Defects of missing BR monomers allowed unambiguous correlation of the force spectra with a single protein (Oesterhelt et al., 2000).

Temperature adjustment

An electric heating stage (Nanoscope Thermoheater, Digital Instruments) was magnetically mounted between the piezo scanner and support. The actual sample temperature was controlled within an accuracy of 1°C using a calibrated digital thermometer. Measurements at 8°C were performed in a cold room. The pH of the buffer (300 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris pH = 7.8) was adjusted at the temperature at which the experiments were performed.

Data analysis

To analyze the force curves, a clear criterion is required that distinguishes curves of BR molecules attached to the AFM tip with different regions of their polypeptide backbone. One suitable criterion is the overall length of the force curve, which reflects the tip-sample distance at which the last force peak occurs. It is obvious that a molecule attached to the cantilever by one of its loops results in a force curve with smaller overall length than that of a molecule attached by one of its termini. It was previously shown that force-extension curves exhibiting an overall length between 60 and 70 nm result from completely unfolded and extended BR molecules which were attached with their C-terminus to the AFM tip (Oesterhelt et al., 2000; Müller et al., 2002). All force curves exhibiting these overall lengths were selected and aligned at the force peak, which occurred at a tip-to-purple membrane separation of ≈25 nm (Figure 1). The reason that the force curves were aligned at this peak is due to the fact that in principle every amino acid of the C-terminal can bind to the AFM tip and that the point of contact (Figure 1, region around 0 nm) is not necessarily located at the tip apex but can also occur at the side of the tip. Additionally, force peaks located within the contact region below 20 nm show a broad variance, making them unsuitable for alignment. To avoid statistical difficulties, we analyzed only relative positions of the peaks. We used identical procedures and criteria to align each data set.

To analyze the side peaks, however, we superimposed every main peak separately (Figure 2). Every single peak of these superimpositions was fitted using the WLC model using a persistence length of 0.4 nm (Rief et al., 1997) and a monomer length of 0.36 nm. We calculated the number of unfolded aa at each peak using the contour length as obtained from the WLC model. When pulling the polypeptide from the cytoplasmic surface, the anchor of the peptide, for example an extracellular loop, was sometimes located at the opposite extracellular surface. In this case, the membrane thickness (≈4 nm) had to be considered and 11 aa (11 × 0.36 nm ≈ 4 nm) were added to the number of aa determined using the WLC model. This allowed calculation of the entire rupture length of the polypeptide. To compare the polypeptide length derived from the WLC fits with the BR structure, we have chosen the atomic model of Mitsuoka et al. (1999).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Norbert Dencher, Tim Salditt, Matthias Rief, Martin Stark and Stephen White for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by the Volkswagenstiftung and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Baldwin J.M. (1993) The probable arrangement of the helices in G protein-coupled receptors. EMBO J., 12, 1693–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G.I. (1978) Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science, 200, 618–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belrhali H., Nollert,P., Royant,A., Menzel,C., Rosenbusch,J.P., Landau,E.M. and Pebay-Peyroula,E. (1999) Protein, lipid and water organization in bacteriorhodopsin crystals: a molecular view of the purple membrane at 1.9 Å resolution. Structure Fold. Des., 7, 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume A. (1983) Apparent molar heat capacities of phospholipids in aqueous dispersion: effects of chain length and head group structure. Biochemistry, 22, 5436–5442. [Google Scholar]

- Booth P.J., Templer,R.H., Meijberg,W., Allen,S.J., Curran,A.R. and Lorch,M. (2001) In vitro studies of membrane protein folding. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 36, 501–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette C.G., Muccio,D.D. and Finney,T.K. (1987) pH dependence of bacteriorhodopsin thermal unfolding. Biochemistry, 26, 7431–7438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C., Macosko,J.C. and Wuite,G.J. (2000) Grabbing the cat by the tail: manipulating molecules one by one. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol., 1, 130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt H.-J., Jaschke,M. and Ducker,W. (1995) Measuring surface forces in aqueous solution with the atomic force microscope. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg., 38, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chignell C.F. and Chignell,D.A. (1975) A spin label study of purple membranes from Halobacterium halobium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 62, 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cladera J., Galisteo,M.L., Sabes,M., Mateo,P.L. and Padros,E. (1992) The role of retinal in the thermal stability of the purple membrane. Eur. J. Biochem., 207, 581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen-Schaumann H., Seitz,M., Krautbauer,R. and Gaub,H.E. (2000) Force spectroscopy with single bio-molecules. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 4, 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammer U., Hegner,M., Anselmetti,D., Wagner,P., Dreier,M., Huber,W. and Güntherodt,H.J. (1996) Specific antigen/antibody interactions measured by force microscopy. Biophys. J., 70, 2437–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmann W., Grandbois,M., Andre,S., Benoit,M., Wehle,A.K., Kaltner,H., Gabius,H.J. and Gaub,H.E. (2000) Differences in zero-force and force-driven kinetics of ligand dissociation from β-galactoside-specific proteins (plant and animal lectins, immunoglobulin G) monitored by plasmon resonance and dynamic single molecule force microscopy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 383, 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E. (1998) Energy landscapes of biomolecular adhesion and receptor anchoring at interfaces explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss., 111, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher T.E., Oberhauser,A.F., Carrion-Vazquez,M., Marszalek,P.E. and Fernandez,J.M. (1999) The study of protein mechanics with the atomic force microscope. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin E.L., Rief,M., Lehmann,H., Ludwig,M., Dornmair,C., Moy,V.T. and Gaub,H. (1995) Sensing specific molecular interactions with the atomic force microscope. Biosens. Bioelectron., 10, 895–901. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz J., Katopodis,A.G., Kolbinger,F. and Anselmetti,D. (1998) Force-mediated kinetics of single P-selectin/ligand complexes observed by atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA., 95, 12283–12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbois M., Beyer,M., Rief,M., Clausen-Schaumann,H. and Gaub,H.E. (1999) How strong is a covalent bond? Science, 283, 1727–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia T. and Freire,E. (1995) Forces and factors that contribute to the structural stability of membrane proteins. BBA-Bioenergetics, 1228, 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanggi P., Talkner,P. and Borkovec,M. (1990) Reaction rate theory—50 years after Kramers. Rev. Mod. Phys., 62, 251–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler L., Heymann,J.B., Engel,A., Kistler,J. and Walz,T. (1998) 2D crystallization of membrane proteins: rationales and examples. J. Struct. Biol., 121, 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupts U., Tittor,J. and Oesterhelt,D. (1999) Closing in on bacteriorhodopsin: progress in understanding the molecule. Annu. Rev. Biophys Biomol. Struct., 28, 367–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmreich E.J.M. and Hofmann,K.-P. (1996) Structure and function of proteins in G-protein coupled signal transfer. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 1286, 285–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann B. and Grubmüller,H. (2000) Dynamic force spectroscopy of molecular adhesion bonds. Phys. Rev. Lett., 84, 6126–6129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili J. (1991) Intermolecular & surface forces. Academic Press Limited, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.B. and Sturtevant,J.M. (1978) Phase transitions of the purple membrane of the Halobacterium halobium. Biochemistry, 17, 911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer M.S., Smith,S.B., Granzier,H.L. and Bustamante,C. (1997) Folding-unfolding transitions in single titin molecules characterized with laser tweezers. Science, 276, 1112–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltover I., Raedler,J.O., Salditt,T., Rothschild,K.J. and Safinya,C.R. (1999) Phase behavior and interactions of the membrane-protein bacteriorhodopsin. Phys. Rev. Lett., 82, 3184–3187. [Google Scholar]

- Kramers H.A. (1940) Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion model of chemical reactions. Physica (Utrecht), 7, 284–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kühlbrandt W. (1992) Two-dimensional crystallization of membrane proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys., 25, 1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyi J.K. (1999) Progress toward an explicit mechanistic model for the light-driven pump, bacteriorhodopsin. FEBS Lett., 464, 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.U., Kidwell,D.A. and Colton,R.J. (1994) Sensing discrete streptavidin-biotin interactions with atomic force microscopy. Langmuir, 10, 354–357. [Google Scholar]

- Luecke H., Richter,H.-T. and Lanyi,J.K. (1998) Proton transfer pathways in bacteriorhodopsin at 2.3 Angstrom resolution. Science, 280, 1934–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecke H., Schobert,B., Richter,H.T., Cartailler,J.P. and Lanyi,J.K. (1999) Structure of bacteriorhodopsin at 1.55 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol., 291, 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek P.E., Lu,H., Li,H., Carrion-Vazquez,M., Oberhauser,A.F., Schulten,K. and Fernandez,J.M. (1999) Mechanical unfolding intermediates in titin modules. Nature, 402, 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel R., Nassoy,P., Leung,A., Ritchie,K. and Evans,E. (1999) Energy landscapes of receptor-ligand bonds explored with dynamic force microscopy. Nature, 397, 50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuoka K., Hirai,T., Murata,K., Miyazawa,A., Kidera,A., Kimura,Y. and Fujiyoshi,Y. (1999) The structure of bacteriorhodopsin at 3.0 Å resolution based on electron crystallography: implication of the charge distribution. J. Mol. Biol., 286, 861–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy V.T., Florin,E.-L. and Gaub,H.E. (1994) Intermolecular forces and energies between ligands and receptors. Science, 266, 257–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D.J., Amrein,M. and Engel,A. (1997) Adsorption of biological molecules to a solid support for scanning probe microscopy. J. Struct. Biol., 119, 172–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller D.J., Kessler,M., Oesterhelt,F., Moeller,C., Oesterhelt,D. and Gaub,H. (2002) Stability of bacteriorhodopsin α-helices and loops analyzed by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Biophys. J., 83, 3578–3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Münster,C. and Salditt,T. (2000) Thermal denaturating of bacteriorhodopsin by X-ray scattering from oriented purple membranes. Biophys. J., 78, 3208–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiya T., Tabushi,I. and Maeda,A. (1987) Circular dichroism study of bacteriorhodopsin-lipid interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 144, 836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberhauser A.F., Marszalek,P.E., Erickson,H.P. and Fernandez,J.M. (1998) The molecular elasticity of the extracellular matrix protein tenascin. Nature, 393, 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberhauser A.F., Marszalek,P.E., Carrion-Vazquez,M. and Fernandez,J.M. (1999) Single protein misfolding events captured by atomic force microscopy. Nat. Struct. Biol., 6, 1025–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhelt D. (1998) The structure and mechanism of the family of retinal proteins from halophilic archaea. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 8, 489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhelt D. and Stoeckenius,W. (1974) Isolation of the cell membrane of Halobacterium halobium and its fraction into red and purple Membrane. Methods Enzymol., 31, 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterhelt F., Oesterhelt,D., Pfeiffer,M., Engel,A., Gaub,H.E. and Müller,D.J. (2000) Unfolding pathways of individual bacterio rhodopsins. Science, 288, 143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot J.L., Gerchmann,S.-E. and Engelmann,D.M. (1987) Refolding of bacteriorhodopsin in lipid bilayers: a thermodynamically controlled two-stage process. J. Mol. Biol., 198, 655–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot J.L. and Engelman,D.M. (2000) Helical membrane protein folding, stability, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 69, 881–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racker E. and Hinkle,P.C. (1974) Effect of temperature on the function of a proton pump. J. Membr. Biol., 17, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford S.E. (2000) Protein folding: progress made and promises ahead. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief M., Gautel,M., Oesterhelt,F., Fernandez,J.M. and Gaub,H.E. (1997) Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science, 276, 1109–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief M., Fernandez,J.M. and Gaub,H.E. (1998a) Elastically coupled two-level-systems as a model for biopolymer extensibility. Phys. Rev. Lett., 81, 4764–4767. [Google Scholar]

- Rief M., Gautel,M., Schemmel,A. and Gaub,H.E. (1998b) The mechanical stability of immunoglobulin and fibronectin III domains in the muscle protein titin measured by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J., 75, 3008–3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief M., Gautel,M. and Gaub,H.E. (2000) Unfolding forces of titin and fibronectin domains directly measured by AFM. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol., 481, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Safinya,C.R., Liang,K.S., Ruppert,A.F. and Rothschild,K.J. (1993) Stabilization of the membrane protein bacteriorhodopsin to 140 C in two-dimensional films. Nature, 366, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shnyrov V.L. and Mateo,P.L. (1993) Thermal transitions in the purple membrane from Halobacterium halobium. FEBS Lett., 324, 237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam S. (1999) The structure of bacteriorhodopsin: an emerging consensus. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 9, 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneva S.G., Caaveiro,J.M., Muga,A. and Goni,F.M. (1995) A pathway for the thermal destabilization of bacteriorhodopsin. FEBS Lett., 367, 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanford C. (1980) The hydrophobic effect. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Tristram-Nagle S., Yang,C.P. and Nagle,J.F. (1986) Thermodynamic studies of purple membrane. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 854, 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S.H. and Wimley,W.C. (1999) Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu. Rev. Biophys Biomol. Struct., 28, 319–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D.A. and Nagle,J.F. (1982) Specific heats of lipid dispersions in single phase regions. Biochim. Biophys Acta, 688, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Xu,G. and Evans,J.S. (1999) A kinetic molecular model of the reversible unfolding and refolding of titin under force extension. Biophys. J., 77, 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]