Abstract

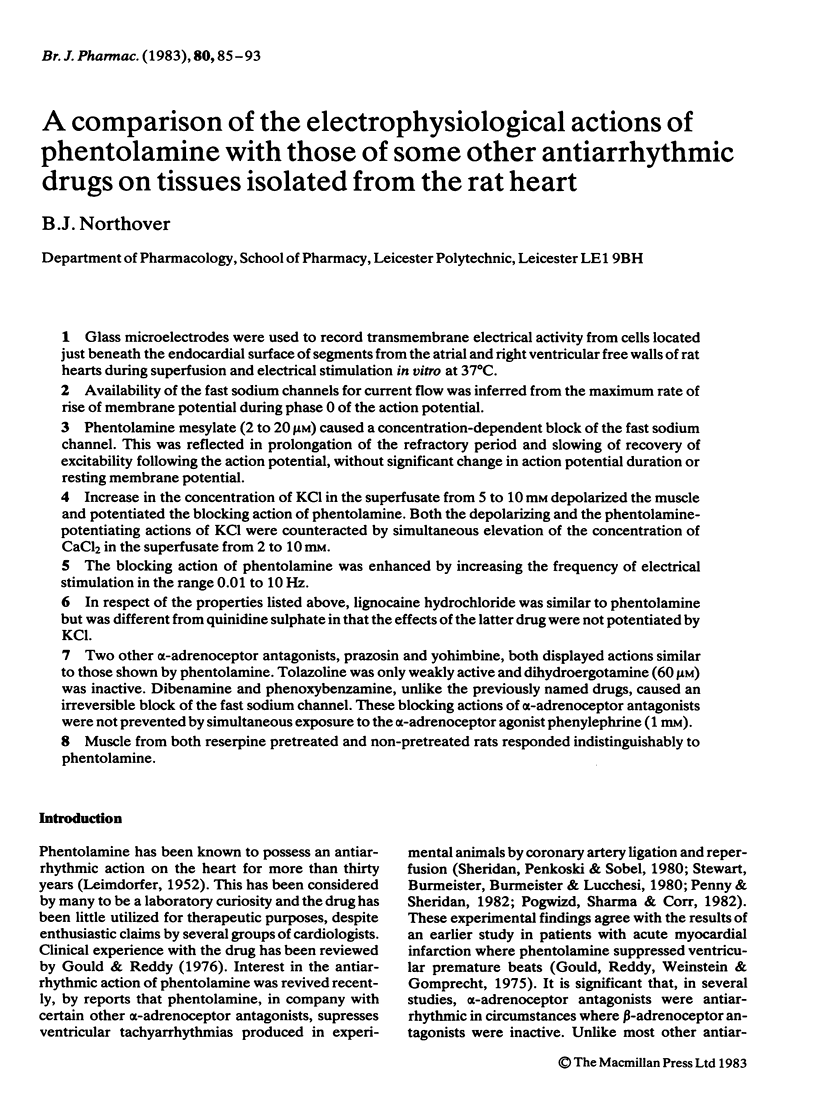

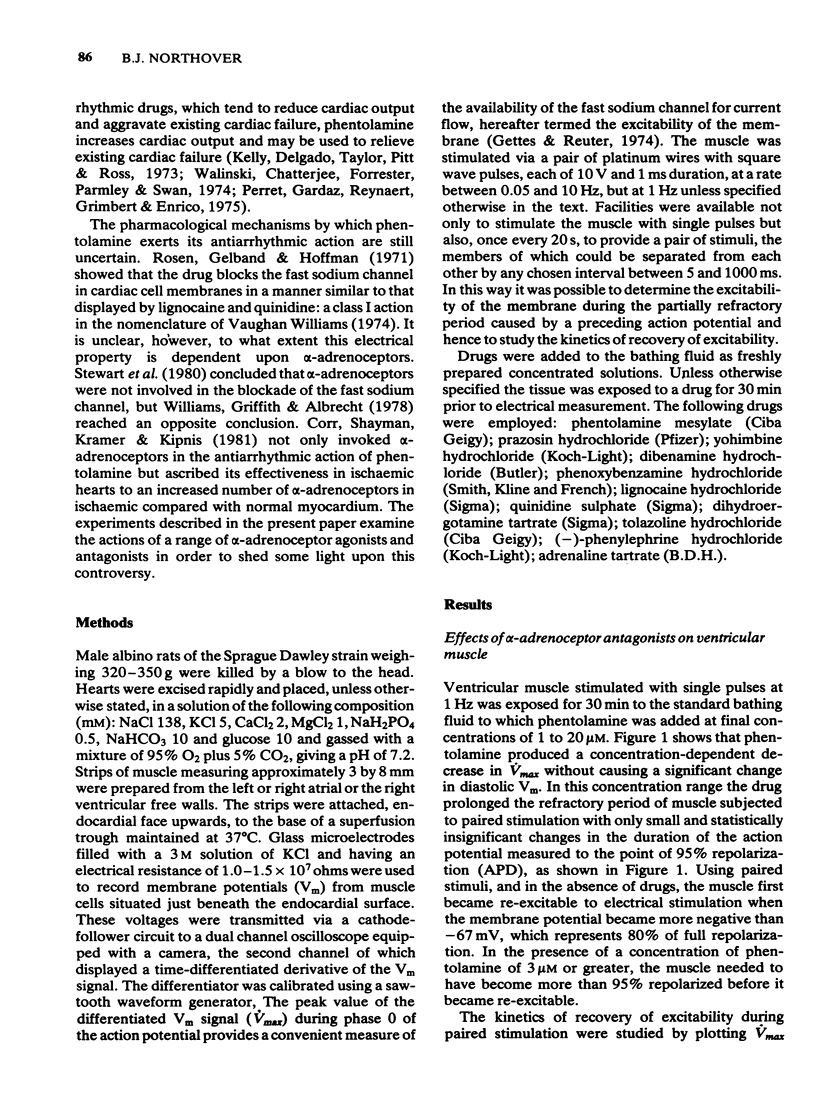

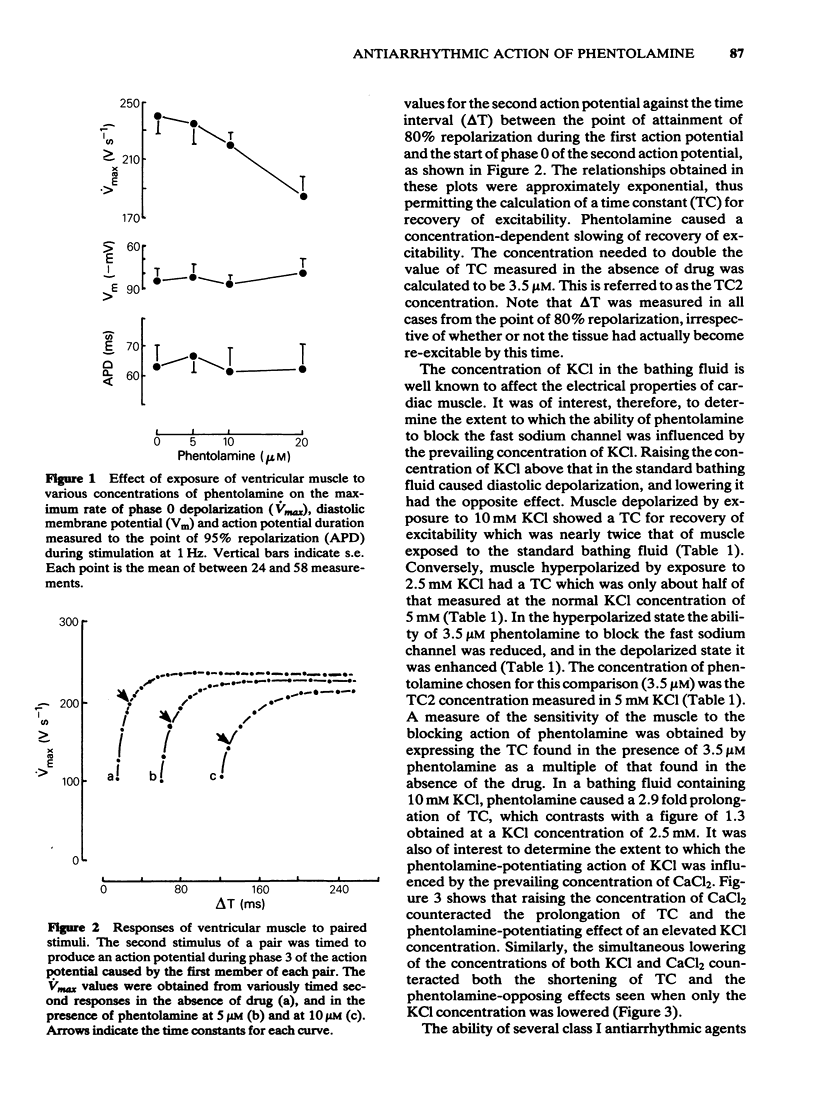

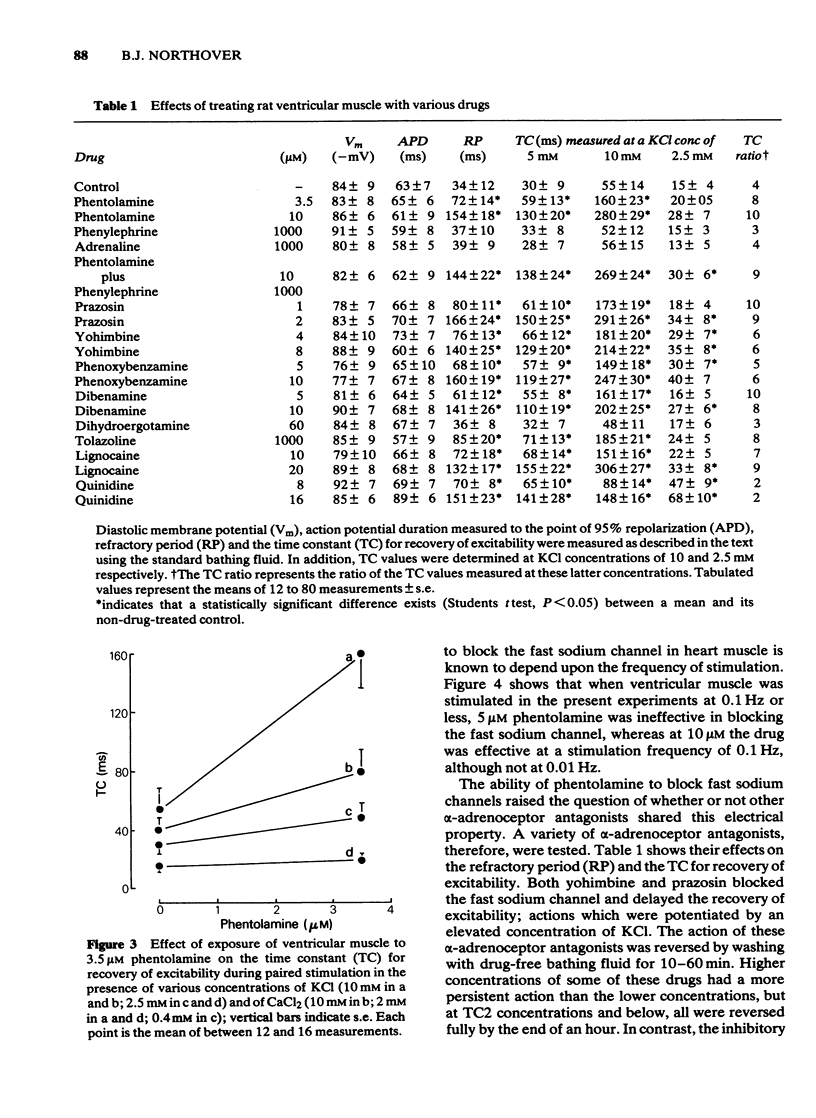

Glass microelectrodes were used to record transmembrane electrical activity from cells located just beneath the endocardial surface of segments from the atrial and right ventricular free walls of rat hearts during superfusion and electrical stimulation in vitro at 37 degrees C. Availability of the fast sodium channels for current flow was inferred from the maximum rate of rise of membrane potential during phase 0 of the action potential. Phentolamine mesylate (2 to 20 microM) caused a concentration-dependent block of the fast sodium channel. This was reflected in prolongation of the refractory period and slowing of recovery of excitability following the action potential, without significant change in action potential duration or resting membrane potential. Increase in the concentration of KCl in the superfusate from 5 to 10 mM depolarized the muscle and potentiated the blocking action of phentolamine. Both the depolarizing and the phentolamine-potentiating actions of KCl were counteracted by simultaneous elevation of the concentration of CaCl2 in the superfusate from 2 to 10 mM. The blocking action of phentolamine was enhanced by increasing the frequency of electrical stimulation in the range 0.01 to 10 Hz. In respect of the properties listed above, lignocaine hydrochloride was similar to phentolamine but was different from quinidine sulphate in that the effects of the latter drug were not potentiated by KCl. Two other alpha-adrenoceptor antagonists, prazosin and yohimbine, both displayed actions similar to those shown by phentolamine. Tolazoline was only weakly active and dihydroergotamine (60 microM) was inactive.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aellig W. H. Venoconstrictor effect of dihydroergotamine in superficial hand veins. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1974;7(2):137–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00561328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal R., Janse M. J., van Eeden I., Werner G., d'Alnoncourt C. N., Durrer D. The effects of lidocaine on intracellular and extracellular potentials, activation, and ventricular arrhythmias during acute regional ischemia in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res. 1981 Sep;49(3):792–806. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.3.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. M., Gettes L. S., Katzung B. G. Effect of lidocaine and quinidine on steady-state characteristics and recovery kinetics of (dV/dt)max in guinea pig ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1975 Jul;37(1):20–29. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D., Stuermer E., Berde B. Studies on the mechanism of action of dihydroergotamine (DHE) on the vascular bed of cat skeletal muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1973 Jun;48(2):331P–332P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. B., Shayman J. A., Kramer J. B., Kipnis R. J. Increased alpha-adrenergic receptors in ischemic cat myocardium. A potential mediator of electrophysiological derangements. J Clin Invest. 1981 Apr;67(4):1232–1236. doi: 10.1172/JCI110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherif N., Scherlag B. J., Lazzara R., Hope R. R. Re-entrant ventricular arrhythmias in the late myocardial infarction period. 4. Mechanism of action of lidocaine. Circulation. 1977 Sep;56(3):395–402. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelin C., Vigne P., Lazdunski M. Biochemical evidence for pharmacological similarities between alpha-adrenoreceptors and voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca++ channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982 Jun 15;106(3):967–973. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettes L. S., Reuter H. Slow recovery from inactivation of inward currents in mammalian myocardial fibres. J Physiol. 1974 Aug;240(3):703–724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould L., Reddy C. V. Phentolamine. Am Heart J. 1976 Sep;92(3):397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(76)80121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govier W. C., Mosal N. C., Whittington P., Broom A. H. Myocardial alpha and beta adrenergic receptors as demonstrated by atrial functional refractory-period changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966 Nov;154(2):255–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govier W. C. Prolongation of the myocardial functional refractory period by phenylephrine. Life Sci. 1967 Jul 1;6(13):1367–1371. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(67)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS A. S., BISTENI A. Effects of sympathetic blockade drugs on ventricular tachycardia resulting from myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1955 Jun;181(3):559–566. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1955.181.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistracher P. Mechanism of action of antifibrillatory drugs. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmakol. 1971;269(2):199–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01003037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. L., Gettes L. S. Effect of acute coronary artery occlusion on local myocardial extracellular K+ activity in swine. Circulation. 1980 Apr;61(4):768–778. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard C. C., Bagwell E. E., Daniell H. B., Freeman B. F. The effects of reserpine on the cardiovascular responses to phentolamine. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1972 Mar;196(1):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirche H., Franz C., Bös L., Bissig R., Lang R., Schramm M. Myocardial extracellular K+ and H+ increase and noradrenaline release as possible cause of early arrhythmias following acute coronary artery occlusion in pigs. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Jun;12(6):579–593. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Cotner C. L. Reproducible and uniform cardiac ischemia: effects of antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Physiol. 1978 Nov;235(5):H574–H580. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.5.H574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem L. M., Katzung B. G. Time- and voltage-dependent interactions of antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977 Nov 14;472(3-4):373–398. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON E. A., McKINNON M. G. The differential effect of quinidine and pyrilamine on the myocardial action potential at various rates of stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1957 Aug;120(4):460–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D. T., Delgado C. E., Taylor D. R., Pitt B., Ross R. S. Use of phentolamine in acute myocardial infarction associated with hypertension and left ventricular failure. Circulation. 1973 Apr;47(4):729–735. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara R., Hope R. R., El-Sherif N., Scherlag B. J. Effects of lidocaine on hypoxic and ischemic cardiac cells. Am J Cardiol. 1978 May 1;41(5):872–879. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret C. l., Gardaz J. P., Reynaert M., Grimbert F., Enrico J. F. Phentolamine for vasodilator therapy in left ventricular failure complicating acute myocardial infarction. Haemodynamic study. Br Heart J. 1975 Jun;37(6):640–646. doi: 10.1136/hrt.37.6.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd S. M., Sharma A. D., Corr P. B. Influences of labetalol a combined alpha- and beta-adrenergic blocking agent on the dysrhythmias induced by coronary occlusion and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1982 Jul;16(7):398–407. doi: 10.1093/cvr/16.7.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen M. R., Gelband H., Hoffman B. F. Effects of phentolamine on electrophysiologic properties of isolated canine purkinje fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1971 Dec;179(3):586–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sada H. Effect of phentolamine, alprenolol and prenylamine on maximum rate of rise of action potential in guinea-pig papillary muscles. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1978 Oct;304(3):191–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00507958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan D. J., Penkoske P. A., Sobel B. E., Corr P. B. Alpha adrenergic contributions to dysrhythmia during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in cats. J Clin Invest. 1980 Jan;65(1):161–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI109647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. R., Burmeister W. E., Burmeister J., Lucchesi B. R. Electrophysiologic and antiarrhythmic effects of phentolamine in experimental coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion in the dog. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1980 Jan-Feb;2(1):77–91. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald R. W., Waxman M. B., Downar E. The effect of antiarrhythmic drugs on depressed conduction and unidirectional block in sheep Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1980 May;46(5):612–619. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walinsky P., Chatterjee K., Forrester J., Parmley W. W., Swan H. J. Enhanced left ventricular performance with phentolamine in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1974 Jan;33(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90737-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. M., James C. A., Maxwell R. A. Effects of lidocaine on the electrophysiological properties of subendocardial Purkinje fibers surviving acute myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1979 Jul;11(7):669–681. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(79)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weld F. M., Coromilas J., Rottman J. N., Bigger J. T., Jr Mechanisms of quinidine-induced depression of maximum upstroke velocity in ovine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1982 Mar;50(3):369–376. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand V., Güggi M., Meesmann W., Kessler M., Greitschus F. Extracellular potassium activity changes in the canine myocardium after acute coronary occlusion and the influence of beta-blockade. Cardiovasc Res. 1979 May;13(5):297–302. doi: 10.1093/cvr/13.5.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. J., Griffith W. H., 3rd, Albrecht C. M. The protective effect of phentolamine against cardiac arrhythmias in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978 May 1;49(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. M. Electrophysiological basis for a rational approach to antidysrhythmic drug therapy. Adv Drug Res. 1974;9:69–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]