Abstract

Antibiograms and relevant genotypes of Korean avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) isolates (n = 101) recovered between 1985 and 2005 were assessed via disc diffusion test, PCR, restriction enzyme analysis, and sequencing. These isolates were highly resistant to tetracycline (84.2%), streptomycin (84.2%), enrofloxacin (71.3%), and ampicillin (67.3%), and most of the tetracycline, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, and ampicillin resistances were associated with tetA and/or tetB, aadA and/or strA-strB, mutations in gyrA and/or parC, and TEM, respectively. Class 1 integrons were detected in 40 isolates (39.6%), and a variety of gene cassettes conferring streptomycin (aadA), gentamicin (aadB), and trimethoprim (dfr) resistances were identified: aadA1a (27.5%), dfrV-orfD (2.5%), aadB-aadA1a (2.5%), dfrI-aadA1a (47.5%), dfrXVII-aadA5 (12.5%), and dfrXII-orfF-aadA2 (7.5%). In addition, several types of common promoters (Pant) of the gene cassettes (hybrid P1, weak P1, or weak P1 plus P2) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms in aadA1a were identified. The results of a chronological analysis demonstrated significant and continuous increases in the frequencies of resistances to several antibiotics (tetracycline, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, ampicillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) and of the relevant resistance genes (tetA, strA-strB, and TEM), mutations in gyrA and parC, and multidrug-resistant APEC strains during the period 2000 to 2005.

Extraintestinal infection with avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) induces colibacillosis in chickens. It is characterized by polyserositis, septicemic shock, and cellulitis and is responsible for enormous economic losses and frequent antibiotic treatment (1, 4, 11, 15). The spread of antibiotic resistance among bacteria has been recognized as an increasing problem in the veterinary and medical fields, and mobile DNA elements, including plasmids, transposons, and integrons, facilitate the proliferation of resistance genes in bacteria (25, 33). The class 1 integron has been identified as the most prevalent of the five classes of integrons in clinical isolates and has been associated with multidrug resistance (MDR) in pathogenic bacteria (16, 31). The class 1 integron acquires resistance genes in the form of gene cassettes via site-specific recombination. Among the same gene cassettes, some nucleotide changes tend to be present, and some of these are shared by other bacteria. Certain of those nucleotide changes can be classified as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and these have proven useful in the fine differentiation of bacterial isolates, as well as in studies of the molecular evolution of class 1 integrons (19, 32). Gene cassettes lack their own promoters, and their expression levels are affected by their proximity to the common promoter, Pant (P1), the strength of promoter P1, and the presence of P2 (9). On the basis of promoter activity, P1 promoters can be classified as strong, hybrid, or weak promoters, and the insertion of 3 guanosines 119 nucleotides downstream of P1 results in the creation of a new, weak promoter, designated P2 (9, 13, 22). Thus far, integron studies have focused primarily on the contents of gene cassettes and have largely overlooked their common promoter structures (19).

Tetracyclines, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, and ampicillin are commonly utilized to treat diseases and promote growth in livestock animals. Although resistances to various antibiotics, including these compounds, have clearly increased, the relevant resistance genes in Korea remain to be elucidated thoroughly. Therefore, we have attempted to characterize the class 1 APEC integrons isolated between 1985 and 2005 with regard to their gene cassettes as well as their promoters and have delineated the relationships between tetracycline, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), and gentamicin resistances and the relevant genes (tetA, tetB, strA-strB, gyrA, parC, and TEM). Additionally, the frequencies of certain resistance genes and antibiograms were compared chronologically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

One hundred one APEC isolates were recovered from Korean chickens suffering from colibacillosis between 1985 and 2005 (Table 1). All of the APEC isolates were identified using VITEK gram-negative identification (GNI) cards (bioMérieux Vitek, Hazelwood, MO). Once identified, the isolates were preserved at −70°C in LB broth containing 20% glycerol (vol/vol) until further studies.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of MDR APEC isolates recovered from Korean chickens

| Period | No. of isolates tested | No. of MDR isolates | Frequency (%) of MDR APEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985-1988 | 15 | 9 | 60.0 |

| 1990-1999 | 35 | 20 | 57.1 |

| 2000-2005 | 51 | 48 | 94.1a |

| Total | 101 | 77 | 76.2 |

Significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the frequencies for 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All isolates were tested for their susceptibilities to seven antimicrobial agents (Table 2) via disc diffusion assay according to CLSI (formerly NCCLS) guidelines (27).

TABLE 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of APEC isolates recovered from Korean chickens

| Antimicrobial drug | Frequency of resistance (% [no. of resistant isolates/total isolates]) to the indicated drug

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985-1988 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2005 | Avg | |

| Streptomycin | 60.0 (9/15) | 80.0 (28/35) | 94.1 (48/51)a | 84.2 (85/101) |

| Tetracycline | 86.7 (13/15) | 68.6 (24/35) | 94.1 (48/51)b | 84.2 (85/101) |

| Enrofloxacin | 26.7 (4/15) | 60.0 (21/35) | 92.2 (47/51)a,b | 71.3 (72/101) |

| Ampicillin | 46.7 (7/15) | 51.4 (18/35) | 84.3 (43/51)a,b | 67.3 (68/101) |

| SXT | 0.0 (0/15) | 31.4 (11/35)a | 52.9 (27/51)a,b | 37.6 (38/101) |

| Gentamicin | 13.3 (2/15) | 22.9 (8/35) | 33.3 (17/51) | 26.7 (27/101) |

| Chloramphenicol | 40.0 (6/15) | 14.3 (5/35) | 9.8 (5/51)a | 15.8 (16/101) |

Significantly increased or decreased (P < 0.05) relative to the frequency for 1985 to 1988.

Significantly increased (P < 0.05) over the frequency for 1990 to 1999.

Detection of class 1 integrons by PCR.

Total APEC DNA was extracted with a G-spin genomic DNA extraction kit (for gram-negative bacteria; iNtRON Biotechnology Co., Seongnam, Korea) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. All isolates were evaluated for the presence of class 1 integrons using the 5′CS-3′CS primer set (23). PCR was conducted as described previously (20).

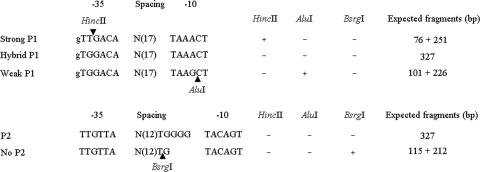

Characterization of Pant by REA and PAGE.

For the rapid and simple characterization of the class 1 integron promoter structures, we designed PCR primer sets for restriction enzyme analysis (REA) and sequencing (IntProF, 5′-ATG CCT CGA CTT CGC TGC T-3′; IntProR, 5′-ACT TTG TTT TAG GGC GAC TGC-3′; amplicon size, 327 bp) and for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Int PT2F, 5′-TGG TAA CGG CGC AGT GGC-3′; Int PT2R, 5′-TTG CTG CTT GGA TGC CCG A-3′; amplicon size, 82 bp). The amplicons generated by the IntProF-IntProR primer set were subsequently treated with HincII and AluI (for P1) as described previously (19) and with BsrgI (for P2) in separate tubes; then they were subjected to electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. PAGE was also conducted with the amplicon for 4 h using a 12% (19:1) polyacrylamide gel at 90 V, and the gel was stained with ethidium bromide. The expected fragments and promoter types are summarized in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for the differentiation of common promoters (P1 and P2) of class 1 integron gene cassettes via REA. Arrowheads indicate enzymatic cleavage sites.

Detection of antibiotic resistance genes by PCR.

Tetracycline and streptomycin resistance genes were PCR amplified using primers targeting the tetracycline efflux genes, tetA and tetB, and the streptomycin phosphorylation genes, strA-strB. The primer sets and PCR conditions adopted were those described in previous studies (28, 34). Of the ampicillin resistance genes, TEM was targeted for PCR amplification. A primer set was designed for the amplification of TEM mutants (TEM-F, 5′-TAC TCA CCA GTC ACA GAA AAG C-3′; TEM-R, 5′-TGC TTA ATC AGT GAG GCA CC-3′; amplicon size, 548 bp) (6, 10). Resistance to enrofloxacin was assessed by determining mutations in gyrA with a primer set for PCR and sequencing (gyrAF, 5′-TAC ACC GGT CAA CAT TGA GG-3′; gyrAR, 5′-TCR ATA CCR CGA CGA CCG TT-3′) and by determining mutations in parC as described previously (12).

Sequencing and sequence analysis.

The PCR amplicons were purified using a PCRquick-spin kit (iNtRON Biotechnology Co., Seongnam, Korea) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA sequences obtained were compared to the information in the GenBank database of the BLAST network of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (2).

Statistical analysis.

The increases and decreases in antibiotic resistance and the frequencies of resistance genes were compared between the periods studied by chi-square and Fisher's exact tests (with 95% confidence intervals), using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0. All experiments in this study were confirmed by more than two repetitions.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

The highest frequencies of resistance detected were those against tetracycline and streptomycin (both 84.2%), followed by those against enrofloxacin (71.3%), ampicillin (67.3%), SXT (37.6%), gentamicin (26.7%), and chloramphenicol (15.8%) (Table 2). Significant increases or decreases in the levels of resistance to tetracycline, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, ampicillin, SXT, and chloramphenicol were found during the periods observed (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Remarkably, the frequency of MDR APEC strains evidencing resistance against at least three different classes of antibiotics increased from 60.0% in the period from 1985 to 1988 and 57.1% in 1990 to 1999 to 94.1% in 2000 to 2005 (P = 0.003 and P = 0.000 for the comparisons of 2000 to 2005 with 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively; P < 0.05 for both comparisons averaged) (Table 1).

Molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance.

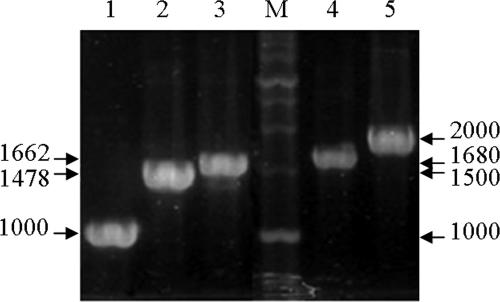

Class 1 integrons were detected in 39.6% of APEC strains (40/101), and the amplicon sizes were variable, at 1,000, 1,478, 1,662, 1,680, and 2,000 bp (Fig. 2; Table 3). Nucleotide sequencing showed aadA1a in the 1,000-bp, dfrV-orfD in the 1,478-bp, dfrI-aadA1a or aadB-aadA1a in the 1,662-bp, dfrXVII-aadA5 in the 1,680-bp, and dfrXII-orfF-aadA2 in the 2,000-bp amplicon (Table 3). aadA1a and aadA5, aadB, and dfr are associated with streptomycin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim resistance, respectively. The nucleotide sequences of aadA1a, dfrV-orfD, dfrI-aadA1a, aadB-aadA1a, dfrXVII-aadA5, and dfrXII-orfF-aadA2 were similar to those of GenBank sequences with accession numbers AB188263, AM231806, AJ884723, AY139602, AY748452, and AB154407, respectively. Nucleotide changes suspected of being SNPs were then evaluated with regard to their frequency via BLAST searches (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The nucleotide sequences of aadA1a in the 1,000-bp and 1,662-bp amplicons differed slightly at codons 201 and 250: AAG (K) versus AGA (R) and GTC (V) versus GTT (V), respectively. Both corresponding codons at 201 and 250 were common, shared by significant numbers of aadA1 sequences registered in the GenBank database. Among the APEC isolates harboring dfrXVII-aadA5, one isolate evidenced a single-nucleotide mutation at codon 7 of dfrXVII, which resulted in an amino acid change from S (TCT) to P (CCT), and another isolate evidenced a silent mutation at codon 149 of aadA5, TCC (S) to TCA (S). However, both codon CCT in dfrXVII and codon TCA in aadA5 were rare, but TCT in dfrXVII and TCC in aadA5 were common, in the GenBank database. The dfrI-aadA1a array of gene cassettes, the prevalence of which increased steeply during the period from 2000 to 2005 (P = 0.003 and P = 0.007 for the comparisons of 2000 to 2005 with 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively; P < 0.05 for both comparisons averaged), was the most prevalent (47.5%), and aadA1a was the second most frequently detected cassette (27.5%) (Table 3). The oldest APEC strain, isolated in 1985, harbored aadA1a. One isolate harboring dfrXVII-aadA5 was found, unexpectedly, to be susceptible to both streptomycin and SXT.

FIG. 2.

Amplified class 1 integron gene cassettes of APEC strains isolated from Korean chickens. Lanes: M, 1-kb molecular weight marker (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Republic of Korea); 1, 1,000 bp; 2, 1,478 bp; 3, 1,662 bp; 4, 1,680 bp; 5, 2,000 bp.

TABLE 3.

Molecular characterization of class 1 integrons in APEC isolates

| Amplicon (no. of bp) | Gene cassette | Relevant resistancea | Promoter

|

No. of APEC isolatesb

|

Frequency (% [no. of resistant isolates/total isolates]) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | 1985-1988 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2005 | ||||

| 1,000 | aadA1a | S | Weak | + | 2 | 5 | 4 | 27.5 (11/40) |

| 1,478 | dfrV-orfD | S-SXT | Weak | − | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.5 (1/40) |

| 1,662 | dfrI-aadA1a | S-SXT | Weak | − | 0 | 2 | 17c | 47.5 (19/40) |

| aadB-aadA1a | G-S | Hybrid | − | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 (1/40) | |

| 1,680 | dfrXVII-aadA5 | S-SXT | Hybrid | − | 1 | 3 | 0 | 10.0 (4/40) |

| — | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 (1/40) | ||||

| 2,000 | dfrXII-orfF-aadA2 | S-SXT | Weak | − | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.0 (2/40) |

| Hybrid | − | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.5 (1/40) | |||

| Total | 4 | 12 | 24 | 39.6 (40/101) | ||||

S, streptomycin; G, gentamicin; —, susceptible.

The frequency of all resistances in a given period taken together, expressed as a percentage (number of resistant isolates/total isolates), was as follows: for 1985 to 1988, 26.7% (4/15); for 1990 to 1999, 34.3% (12/35); and for 2000 to 2005, 47.1% (24/51).

The frequency of this amplicon was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in 1985 to 1988 (0/19) and 1990 to 1999 (2/19).

Tetracycline resistance was not associated with the class 1 integron, and tetA and tetB were detected via PCR. tetA was detected in 40.0% and 42.9% of APEC isolates during 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively, but its frequency during 2000 to 2005 increased steeply compared with both periods, to 78.4% (P = 0.009 and P = 0.001 for the comparisons of 2000 to 2005 with 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively; P < 0.05 for both comparisons averaged) (Table 4). tetB was present in an average of 18.8% of APEC isolates, and its frequency remained relatively stable during the periods of observation (Table 4). Isolates positive for both tetA and tetB (5.9%) and negative for both but still tetracycline resistant (5.0%) were observed (Table 4). Therefore, the majority of tetracycline resistance in APEC isolates could be attributed to tetA and/or tetB (94.1% 80/85).

TABLE 4.

Relationships between antibiotic resistances and genotypes

| Antibiotic | Genotype | Frequency of APEC isolates (% [no. of resistant isolates/total isolates])

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985-1988 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2005 | Avg | ||

| Tetracycline | tetA+ tetB+ | 0.0 (0/15) | 5.7 (2/35) | 7.8 (4/51) | 5.9 (6/101) |

| tetA+ | 40.0 (6/15) | 37.1 (13/35) | 70.6 (36/51) | 54.5 (55/101) | |

| tetB+ | 26.7 (4/15) | 22.9 (8/35) | 13.7 (7/51) | 18.8 (19/101) | |

| tetA and tetB negative | 33.3 (5/15) | 34.3 (12/35) | 7.8 (4/51) | 20.8 (21/101) | |

| Streptomycin | aadA+ strA-strB+ | 6.7 (1/15) | 22.9 (8/35) | 41.2 (21/51) | 29.7 (30/101) |

| aadA+ | 20.0 (3/15) | 8.6 (3/35) | 5.9 (3/51) | 8.9 (9/101) | |

| strA-strB+ | 26.7 (4/15) | 25.7 (9/35) | 43.1 (22/51) | 34.7 (35/101) | |

| aadA and strA-strB negative | 46.7 (7/15) | 42.9 (15/35) | 9.8 (5/51) | 26.7 (27/101) | |

| Ampicillin | TEM | 33.3 (5/15) | 31.4 (11/35) | 60.8 (31/51) | 46.5 (47/101) |

In an effort to investigate streptomycin resistance genes other than aadA, PCR directed to strA-strB was conducted. strA-strB was detected in 33.3% and 48.6% of isolates during 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively, but its frequency increased steeply compared with both periods, to 84.3%, during 2000 to 2005 (P = 0.000 and P = 0.001 for the comparisons of 2000 to 2005 with 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively; P < 0.05 for both comparisons averaged) (Table 4). Of the APEC isolates, 29.7%, 34.7%, and 8.9% harbored both aadA and strA-strB, strA-strB alone, and aadA alone, respectively, and 10.9% were negative for both but still streptomycin resistant (Table 4). Therefore, 76.5% (65/85) of the streptomycin resistance in APEC isolates could be attributed to strA-strB.

Most of the enrofloxacin-resistant APEC isolates possessed mutations at residue 83 and/or residue 87 in the quinolone resistance-determining region of gyrA (88.9% 64/72) and at residue 80 in its analogue, parC (72.2% 52/72). Leucine and isoleucine replaced the serines at residue 83 in gyrA and residue 80 in parC, respectively, but various amino acids (asparagine, alanine, glycine, histidine, and tyrosine) replaced the aspartic acid at residue 87 in gyrA (Table 5). The frequencies of the double mutations of gyrA and the single mutation of parC were significantly increased from the period 1990 to 1999 (28.6 and 38.1%, respectively) to the period 2000 to 2005 (85.1 and 91.5%, respectively) (P = 0.000 and P < 0.05, respectively) (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Molecular characterization of enrofloxacin-resistant APEC isolates

|

gyrA

|

parC

|

No. of isolates with the indicated patternb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid at position:

|

Typea | Amino acid at position 80 | Type | 1980-1988 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2005 | Total | |

| 83 | 87 | |||||||

| S | D | wt | S | wt | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| S | N | mt | S | wt | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| L | D | mt | S | wt | 0 | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| L | D | mt | I | mt | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| L | A | mt | I | mt | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| L | G | mt | I | mt | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 |

| L | H | mt | I | mt | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| L | N | mt | I | mt | 0 | 4 | 26 | 30 |

| L | Y | mt | I | mt | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Total | 4 (25.0, 25.0) | 21 (28.6, 38.1)c | 47 (85.1, 91.5)c | 72 (66.7, 72.2) | ||||

wt, wild type; mt, mutant type.

Numbers in parentheses after totals are frequencies (percentages) of double mutations in gyrA, followed by the frequencies of mutation in parC.

Significant differences (P = 0.000, P < 0.05).

Most of the ampicillin resistance was associated with TEM. TEM was detected in 33.3% and 31.4% of APEC isolates during the periods 1985 to 1988 and 1990 to 1999, respectively, but its frequency during 2000 to 2005 increased, to 60.8%. The frequency during 2000 to 2005 was significantly higher than that in 1990 to 1999 (P = 0.009) (Table 4).

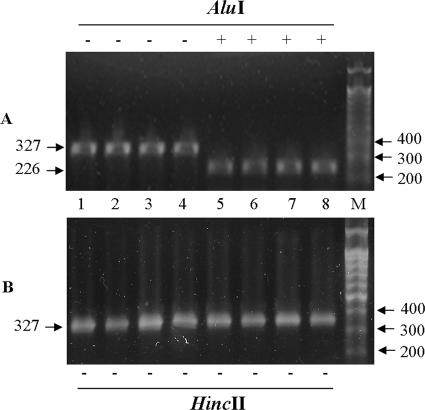

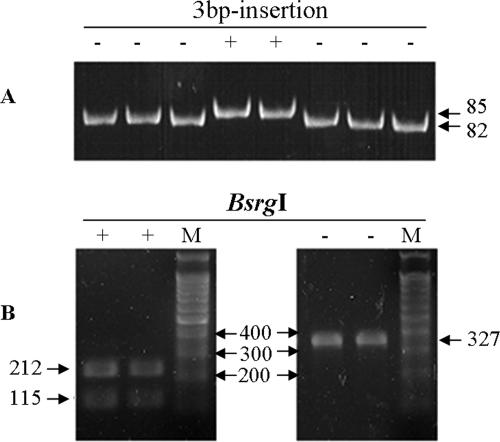

Molecular characterization of common promoters of gene cassettes.

Amplicons harboring weak P1 promoters were not digested by HincII but were digested by AluI, and amplicons harboring hybrid P1 promoters were not digested by either of the enzymes. Strong P1 promoters, digested only by HincII, were not detected among the APEC isolates assessed in this study. A 3-nucleotide insertion in P2 resulted in a gel shift, and the amplicons either were (P2 negative) or were not (P2 positive) digested by BsrgI. Therefore, 7, 22, and 11 isolates of APEC harbored hybrid, weak P1, and weak P1 plus P2 promoters, respectively (Table 3; Fig. 1, 3, and 4). All amplicons utilized in this promoter study were sequenced, and all of the nucleotide variations were verified.

FIG. 3.

Molecular typing of P1 by REA. Each lane represents an individual isolate. (A) REA with AluI. Lanes 1 to 4, no cut by AluI; lanes 5 to 8, cut by AluI; M, 100-bp molecular weight marker (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea). (B) REA with HincII. Lanes 1 to 8, individual isolates showing no cut by HincII.

FIG. 4.

Molecular typing of P2. Each lane represents an individual isolate. (A) Molecular typing by PAGE. A 3-bp (GGG) insertion (85 bp) resulted in the creation of a new promoter, P2, which could be distinguished from the 82-bp promoter by an upward shift of the amplicon. (B) Molecular typing by REA (BsrgI). The 3-bp insertion destroys the enzyme site of BsrgI, and the enzyme does not recognize the P2 promoter.

DISCUSSION

The APEC antibiograms generated in the present study were similar to those of recent intestinal E. coli isolates obtained from poultry in Korea (18). Tetracycline and streptomycin have been utilized for several decades, and resistance to these antibiotics has increased to more than 80% (3, 18, 37). Streptomycin remains in regular use in Korea, and tetracycline is one of the antibiotics most frequently employed, primarily as a feed additive in the poultry industry. The average resistance of the APEC isolates during the periods observed was found to be approximately 80%, but resistance during the 2000-to-2005 period was in excess of 94%. Therefore, preventive and therapeutic effects on APEC strains should no longer be expected from these antibiotics. The relevant antibiograms differ from nation to nation, and they also differ with the origins of bacteria, as a result of differing exposures and selection by different antibiotics. Rates of resistance against enrofloxacin and ampicillin were highest, but resistance to chloramphenicol during the period 2000 to 2005 was lowest, a result consistent with the reports of other studies (3, 18, 35, 37). Enrofloxacin is one of the most frequently employed prophylactic antibiotics, but chloramphenicol was seldom used in the Korean poultry industry during 2000 to 2005.

Only some of the resistance detected against streptomycin, gentamicin, and SXT could be attributed to class 1 integrons. The dfrXII-orfF-aadA2 array of gene cassettes was most frequently detected in avian intestinal E. coli isolates during the 2000-to-2005 period, but dfrI-aadA1a was most frequently detected in APEC isolates during 2000 to 2005 in the present study (18). Therefore, the structures and prevalences of gene cassettes differed substantially among E. coli isolates. However, the structures and frequencies of the gene cassettes of APEC isolates from different countries were similar to each other (30, 35). The high frequencies of aadA and dfr can be attributed to selection pressures exerted by streptomycin and trimethoprim, and this observation may be attributed to the frequent prophylactic use of streptomycin and trimethoprim in poultry farms.

SNPs can provide selective advantages to bacteria over the course of a single infection, epidemic spread, or the long-term evolution of virulence (32). To be accepted as a SNP, a single-nucleotide mutation should be fairly common among compared genetic populations and should also be associated with the biological functions of the protein. One APEC isolate harboring aadB-aadA1a evidenced a single-nucleotide mutation, which resulted in the R201K amino acid change in aadA1a. This mutation was detected in other aadA1a sequences in GenBank (accession numbers AY046276, AY309066, AY602405, D1166553, DQ663487, and Y18050), but the biological effects of the mutation remain to be elucidated thoroughly. In addition, the nucleotide sequence difference at codon 250 of aadA1, GTC (V) versus GTT (V), results in no amino acid alteration, but GTC and GTT were selected preferentially by single-cassette (aadA1a) and two-cassette (aadB-aadA1a or dfrI-aadA1a) class 1 integrons, respectively. Our BLAST search revealed that GTC was also detectable in the oligocassette class 1 integrons in the GenBank database (AF550679, DQ522235, and DQ522239). The aadA1 cassette has spread throughout a variety of bacterial species over several decades (36), and associated nucleotide changes are likely to occur. The distribution of different genotypes of aadA1 in different arrays of gene cassettes implies frequent exchanges of gene cassettes under conditions of antibiotic selection pressure and other environmental, metabolic, or physiological stressors. Therefore, the provisional SNPs observed in aadA1a allowed for a more delicate analysis of the evolution pathways of class 1 integrons, as well as the molecular differentiation of clinical isolates harboring the same gene cassette arrays.

The massive and long-term use of antibiotics for therapy and animal growth promotion in the livestock industry has selected for drug resistances (24). In Korea, the resistance to tetracycline was the highest and increased significantly during the period from 2000 to 2005 over that in 1990 to 1999. In contrast to tetA, which confers resistance against tetracycline, oxytetracycline, and chlortetracycline, tetB provides additional resistance against doxycycline (8). The relative prevalences of tetA and tetB differ according to the origins of E. coli strains, but tetA was more prevalent than tetB in Korea, as has also been reported in studies conducted in other countries (7, 21). The steep increase in the proportion of E. coli strains encoding tetA during the period from 2000 to 2005 could be attributed to the continued utilization of chlorotetracycline and oxytetracycline as feed additives, as well as for prophylaxis. The relatively low frequency of tetB during the observation periods could be explained by a strong negative association between tetA and tetB, which was probably due to plasmid incompatibility (5, 17, 26).

The frequency of APEC isolates positive for strA-strB only or for both aadA and strA-strB increased markedly during 2000 to 2005. The increase in the frequency of strA-strB and the acquisition of strA-strB in aadA-harboring APEC isolates reflect the selection of APEC strains harboring strA-strB. In contrast to aadA, the strA and strB genes have been suggested to confer high-level resistance to streptomycin, and E. coli strains positive for both evidenced the highest observed MICs (34). The majority of streptomycin products in Korea are used on poultry, and antibiotic selection may be related to the increase in the frequency of strA-strB.

According to the results of a promoter study with a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assay, the relative strengths of strong P1, weak P1 plus P2, and hybrid P1 to weak P1 promoters increased approximately 32-fold, 16-fold, and 3.5-fold, respectively (22). Among the APEC isolates evaluated in the present study, strong P1 promoters were absent, but isolates positive for both P1 and P2 were detected at a percentage of 27.5% (11/40). The frequency of strA-strB in the weak P1-plus-P2-positive APEC isolates was 27.3% (3/11), but its frequency in weak P1- and hybrid P1-positive APEC isolates was 96.6% (28/29). All of the weak P1-plus-P2-positive APEC variants harbored the single cassette aadA1a, but others possessed more than two cassettes with streptomycin resistance genes, positioned distantly from the promoter. The expression level of a gene cassette is affected by its proximity to the common promoter (9). Therefore, it appeared that the low level of expression of streptomycin resistance among APEC isolates resulted in the recruitment of the additional resistance genes strA-strB under conditions of streptomycin pressure. The antibiograms of the APEC isolates that harbored class 1 integrons were coincident with their gene cassettes, with the exception of one isolate. This isolate harbored hybrid P1 and was sensitive to streptomycin and SXT. In some cases, discordance of aadA with the antibiogram has been reported, and the influence of nonintegrated and nonexpressed gene cassettes has been suggested (21). However, we detected a class 1 integron and were unable to detect any nonsense mutations, deletion, or insertion mutations resulting in stop codons within the coding regions of dfrXVII and aadA5. Therefore, mechanisms other than the nonintegration of the gene cassette into the class 1 integron may be involved in the silence of gene cassettes.

Resistance to quinolones in APEC is primarily related to mutations in gyrA (35, 37), and double mutations of gyrA and additional mutations in parC produce higher levels of resistance (12, 35, 37). The substitution S83L was most frequently observed among substitutions in the quinolone resistance-determining region of gyrA (87.5%), and strains with the substitutions S83L, D87N, and S80I were most frequent (41.7%) among quinolone-resistant APEC isolates, results similar to those of other reports (35, 37). The frequencies of double mutations in gyrA and the single mutation in parC increased steeply during the period from 2000 to 2005; thus, quinolone resistance became a more serious problem with regard to quantity as well as quality. Most of the quinolone-resistant APEC strains possessed at least one mutation in gyrA and/or parC, but eight enrofloxacin-resistant strains (11.1%) in the present study showed no known mutations in gyrA or parC. Mutations of other genes, such as gyrB and parE, are also associated with quinolone resistance, but usually they are coincident with mutations of gyrA and/or parC (12, 35, 37). In mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, the expression level of the AcrAB efflux pump was strongly correlated with resistances to ciprofloxacin and a wide variety of compounds such as fusidic acid, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, norfloxacin, and penicillin (14, 29). Seven out of the eight enrofloxacin-resistant strains showed intermediate resistance to chloramphenicol, and six without tetA or tetB were resistant or intermediately resistant to tetracycline. Therefore, further study of the association of the AcrAB efflux pump with enrofloxacin resistance in these strains is required.

The frequency of TEM-positive APEC strains increased markedly from 2000 to 2005. The frequencies of TEM among ampicillin-resistant APEC strains were 71.4% (5/7), 61.1% (11/18), and 72.1% (31/43) during 1985 to 1988, 1990 to 1999, and 2000 to 2005, respectively, and TEM has been the major beta-lactamase among APEC strains in Korea.

In conclusion, the frequencies of resistances to several antibiotics (tetracycline, streptomycin, enrofloxacin, ampicillin and SXT), relevant resistance genes (tetA, strA-strB, and TEM) and mutations in gyrA and parC, and MDR APEC strains have increased during the observation periods of this study. Studies of SNPs and promoter structure may prove beneficial for our knowledge of class 1 integron transmission, as well as for the evolution of and relationship between antibiotic resistances and genotypes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Technology Development Program of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and by a Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2006-005-J02901).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altekruse, S. F., F. Elvinger, K. Y. Lee, L. K. Tollefson, E. W. Pierson, J. Eifert, and N. Sriranganathan. 2002. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Escherichia coli strains from a turkey operation. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 221:411-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, A. F., W. Gish, E. W. Miller, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass, L., C. A. Liebert, M. D. Lee, A. O. Summers, D. G. White, S. G. Thayer, and J. J. Maurer. 1999. Incidence and characterization of integrons, genetic elements mediating multiple-drug resistance, in avian Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2925-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco, J. E., M. Blanco, A. Mora, and J. Blanco. 1997. Prevalence of bacterial resistance to quinolones and other antimicrobials among avian Escherichia coli strains isolated from septicemic and healthy chickens in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2184-2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerlin, P., R. Travis, C. L. Gyles, R. Reid-Smith, N. Janecko, H. Lim, V. Nicholson, S. A. McEwen, R. Friendship, and M. Archambault. 2005. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of Escherichia coli isolates from swine in Ontario. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6753-6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan, A., N. Shapir, and M. J. Sadowsky. 2004. Frequency and distribution of tetracycline resistance genes in genetically diverse, nonselected, and nonclinical Escherichia coli strains isolated from diverse human and animal sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2503-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chopra, I., S. Shales, and P. Ball. 1982. Tetracycline resistance determinants from groups A to D vary in their ability to confer decreased accumulation of tetracycline derivatives by Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:689-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collis, C. M., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:155-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Gheldre, Y., V. Avesani, C. Berhin, M. Delmée, and Y. Glupczynski. 2003. Evaluation of oxoid combination discs for detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:591-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dho-Moulin, M., and J. M. Fairbrother. 1999. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC). Vet. Res. 30:299-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett, M. J., Y. F. Jin, V. Ricci, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Contribution of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2380-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fluit, A. C., and F. J. Schmitz. 1999. Class 1 integrons, gene cassettes, mobility, and epidemiology. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giraud, E., A. Cloeckaert, D. Kerboeuf, and E. Chaslus-Dancla. 2000. Evidence for active efflux as the primary mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1223-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gyles, C. L. 1994. Diseases due to Escherichia coli in poultry, p. 237-259. In C. L. Gyles (ed.), Escherichia coli in domestic animals and humans. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 16.Hall, R. M., and H. W. Stokes. 1993. Integrons: novel DNA elements which capture genes by site-specific recombination. Genetica 90:115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, C. S., D. J. Osborne, and J. Stanley. 1992. Enterobacterial tetracycline resistance in relation to plasmid incompatibility. Mol. Cell. Probes 6:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang, H. Y., Y. S. Jeong, J. Y. Oh, S. H. Tae, C. H. Choi, D. C. Moon, W. K. Lee, Y. C. Lee, S. Y. Seol, D. T. Cho, and J. C. Lee. 2005. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and class 1 integrons found in Escherichia coli isolates from humans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:639-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, T. E., H. J. Kwon, S. H. Cho, S. Kim, B. K. Lee, H. S. Yoo, Y. H. Park, and S. J. Kim. 22 November 2006. Molecular differentiation of common promoters in Salmonella class 1 integrons. J. Microbiol. Methods. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet. 2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kwon, H. J., T. E. Kim, S. H. Cho, J. G. Seol, B. J. Kim, J. W. Hyun, K. Y. Park, S. J. Kim, and H. S. Yoo. 2002. Distribution and characterization of class 1 integrons in Salmonella enterica serotype Gallinarum biotype Gallinarum. Vet. Microbiol. 89:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanz, R., P. Kuhnert, and P. Boerlin. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance and resistance gene determinants in clinical Escherichia coli from different animal species in Switzerland. Vet. Microbiol. 91:73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lévesque, C., S. Brassard, J. Lapointe, and P. H. Roy. 1994. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene 142:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lévesque, C., L. Piche, C. Larose, and P. H. Roy. 1995. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:185-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy, S. B. 1998. Multidrug resistance: a sign of the times. N. Engl. J. Med. 338:1376-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebert, C. A., R. M. Hall, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:507-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maynard, C., J. M. Fairbrother, S. Bekal, F. Sanschagrin, R. C. Levesque, R. Brousseau, L. Masson, S. Larivière, and J. Harel. 2003. Antimicrobial resistance genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O149:K91 isolates obtained over a 23-year period from pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3214-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard M2-A8. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 28.Ng, L. K., M. R. Mulvey, I. Martin, G. A. Peters, and W. Johnson. 1999. Genetic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian isolates of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium DT104. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:3018-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikaido, H., M. Basina, V. Nguyen, and E. Y. Rosenberg. 1998. Multidrug efflux pump AcrAB of Salmonella typhimurium excretes only those beta-lactam antibiotics containing lipophilic side chains. J. Bacteriol. 180:4686-4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nógrády, N., J. Pászti, H. Pikó, and B. Nagy. 2006. Class 1 integrons and their conjugal transfer with and without virulence-associated genes in extra-intestinal and intestinal Escherichia coli of poultry. Avian Pathol. 35:349-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Recchia, G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sokurenko, E. V., D. L. Hasty, and D. L. Dykhuizen. 1999. Pathoadaptive mutations: gene loss and variation in bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 7:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speer, B. S., N. B. Shoemaker, and A. A. Salyers. 1992. Bacterial resistance to tetracycline: mechanisms, transfer, and clinical significance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:387-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sunde, M., and M. Norström. 2005. The genetic background for streptomycin resistance in Escherichia coli influences the distribution of MICs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:87-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, H., S. Chen, D. G. White, S. Zhao, P. McDermott, R. Walker, and J. Meng. 2004. Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from diseased chickens and swine in China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3483-3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu, H. S., J. C. Lee, H. Y. Kang, D. W. Ro, J. Y. Chung, Y. S. Jeong, S. H. Tae, C. H. Choi, E. Y. Lee, S. Y. Seol, Y. C. Lee, and D. T. Cho. 2003. Changes in gene cassettes of class 1 integrons among Escherichia coli isolates from urine specimens collected in Korea during the last two decades. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5429-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, S., J. J. Maurer, S. Hubert, J. F. De Villena, P. F. McDermott, J. Meng, S. Ayers, L. English, and D. G. White. 2005. Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characterization of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 107:215-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]