Abstract

Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus (NiV) constitute the Henipavirus genus of paramyxoviruses, both fatal in humans and with the potential for subversion as agents of bioterrorism. Binding of the HeV/NiV attachment protein (G) to its receptor triggers a series of conformational changes in the fusion protein (F), ultimately leading to formation of a postfusion six-helix bundle (6HB) structure and fusion of the viral and cellular membranes. The ectodomain of paramyxovirus F proteins contains two conserved heptad repeat regions, the first (the N-terminal heptad repeat [HRN]) adjacent to the fusion peptide and the second (the C-terminal heptad repeat [HRC]) immediately preceding the transmembrane domain. Peptides derived from the HRN and HRC regions of F are proposed to inhibit fusion by preventing activated F molecules from forming the 6HB structure that is required for fusion. We previously reported that a human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) F peptide effectively inhibits infection mediated by the HeV glycoproteins in pseudotyped-HeV entry assays more effectively than the comparable HeV-derived peptide, and we now show that this peptide inhibits live-HeV and -NiV infection. HPIV3 F peptides were also effective in inhibiting HeV pseudotype virus entry in a new assay that mimics multicycle replication. This anti-HeV/NiV efficacy can be correlated with the greater potential of the HPIV3 C peptide to interact with the HeV F N peptide coiled-coil trimer, as evaluated by thermal unfolding experiments. Furthermore, replacement of a buried glutamic acid (glutamic acid 459) in the C peptide with valine enhances antiviral potency and stabilizes the 6HB conformation. Our results strongly suggest that conserved interhelical packing interactions in the F protein fusion core are important determinants of C peptide inhibitory activity and offer a strategy for the development of more-potent analogs of F peptide inhibitors.

Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus (NiV) are emerging zoonotic paramyxoviruses that cause potentially fatal disease in humans. HeV was first isolated during an outbreak of respiratory illness in Australia (31); during that outbreak, the illness was fatal in horses and in one person. Another person, who had assisted during an autopsy on a HeV-infected horse, died 1 year later due to consequent meningoencephalitis (33). In 1998, outbreaks of severe and highly fatal encephalitis in persons with exposure to pigs in Malaysia and Singapore were found to be caused by a newly identified virus closely related to HeV, named NiV (9, 14). These two viruses are quite homologous to each other but less related to other members of the paramyxovirus family; evaluation of the unique features of HeV and NiV led to their assignment to a new genus, called Henipavirus (44), within the Paramyxovirinae subfamily. Because these viruses are harbored in fruit bats (“flying foxes”) of the genus Pteropus (27), a mammalian reservoir whose range is vast, they have the capability to cause disease over a large area and in new regions where disease has not been seen previously. NiV has continued to reemerge in Bangladesh, causing fatal encephalitis in humans, and for the first time, person-to-person transmission appears to have been a primary mode of spread (6, 13, 16). In addition, the recent NiV outbreaks appeared to involve direct transmission of the virus from its natural host, the flying fox, to humans. Elucidation of the molecular biology of these viruses has advanced rapidly, aided significantly by the accumulating body of knowledge about paramyxovirus biology.

To initiate the first step of infection, the henipavirus F proteins, like all other paramyxovirus F proteins, mediate fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane (22, 34). The paramyxovirus F proteins belong to the group of “class I” fusion proteins (reviewed in reference 10), which also includes the influenza hemagglutinin protein, the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) fusion protein, and the Ebola virus fusion protein. In the class I fusion mechanism, the triggers that initiate a series of conformational changes in F leading to membrane fusion differ depending on which pathway the virus uses to enter the cell and thus whether fusion needs to occur at the surface at neutral pH or in the endosome.

The paramyxovirus fusion process occurs at the surface of the target cell, at neutral pH, like that for HIV-1. Over the last several years, work from us and others has shown that interaction of the paramyxovirus attachment protein (HN, H, or G) with the target cell is required in order for F to promote membrane fusion during viral infection (15, 17, 22, 30). HeV and NiV G is a membrane glycoprotein with a structure similar to those of other paramyxovirus attachment proteins (44). HeV and NiV require both their F protein and their receptor-binding protein (G) in order to mediate fusion, and the interaction of HN (or G in the case of the henipaviruses) with F is thought to trigger a conformational change in F, thus promoting fusion (22, 36, 38, 42).

A model for the multistep process of paramyxovirus F triggering and fusion has been proposed previously (29). The membrane-anchored subunit of the F protein contains two hydrophobic domains: the fusion peptide, which inserts into the cellular target membrane during fusion, and the transmembrane-spanning domain. Each of these domains is adjacent to one of two conserved heptad repeat (HR) regions: the fusion peptide is adjacent to the N-terminal HR (HRN), and the transmembrane domain is adjacent to the C-terminal HR (HRC). Once F is activated, the fusion peptide inserts into the target membrane, first generating a transient intermediate that is anchored to both viral and cell membranes and then refolding and assembling into a fusogenic six-helix bundle (6HB) structure as the HRN and HRC associate into a tight complex. The refolding of F to its final stable form relocates the fusion peptides; TM anchors to the same end of the coiled coil, bringing the viral and cell membranes together, and is the driving force for membrane fusion (40). The coordinated series of conformational changes undergone by the F protein after its activation thus accomplishes membrane fusion, and interfering with this process is the basis of our antiviral strategy.

Peptides derived from the HRN and HRC regions of F protein that interfere with fusion intermediates of F (23, 39, 49) are candidate molecules for impeding entry. Such peptides can interact with fusion intermediates of paramyxovirus F proteins (4, 23, 26, 39, 46, 49). The HRC peptide regions of a number of paramyxoviruses, including Sendai virus, measles virus, Newcastle disease virus, respiratory syncytial virus, simian virus 5, HeV, and NiV, can inhibit the homologous virus infectivity (19, 23, 39, 47, 49, 51, 52). The ability of HR peptides to interfere with the class I fusion process has led to the creation of a clinically effective peptide inhibitor of HIV-1 fusion (enfuvirtide [T-20; Trimeris, Inc.]) (11, 20, 45, 46). The success of T-20 as a therapy for HIV-1 infection supports the concept of designing effective therapies based on understanding the mechanism of viral fusion and the use of HRC peptides as antivirals in general.

In order to investigate various strategies for perturbing specific steps in the viral entry process, we have developed screening assays for anti-HeV neutralizing antibodies and antiviral compounds. We pseudotyped HeV glycoproteins onto a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) that expresses red fluorescent protein (RFP) but lacks VSV G, and the resulting pseudotyped virus (VSV-ΔG-RFP-HeV F/G) was used in neutralization experiments and in a system that mimics multicycle replication.

In recent experiments, we showed that heterotypic peptides based on human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) F HRC sequences are effective at inhibiting HeV fusion and entry of HeV pseudotyped viruses, far more effective than the comparable HeV-derived peptides (35). These HPIV3-derived peptides are, in fact, even without modifications such as N-pegylation, far more effective than other antiviral peptides currently proposed as candidate henipavirus antiviral compounds (5). The in vitro potency of the “parent” anti-HeV peptide derived from HPIV3 HRC is comparable to that of T-20 for HIV-1. Since modifications made to T-20 were found to extend the peptide's plasma half-life, greatly enhancing its clinical efficacy, we have incorporated modifications that should enhance utility into the design of our peptides.

In order to investigate the mechanism for heterotypic anti-HeV potency of the HPIV3-derived peptide, we have designed and constructed soluble models of the homotypic and chimeric fusion cores of the HeV and HPIV3 F proteins. These polypeptides, designated N42(L6)C33, consist of the N42 (HRN) and C33 (HRC) peptides connected via short peptide linkers. We used the recombinant N42(L6)C33 peptides to characterize the abilities of N42 and C33 peptides derived from HeV and HPIV3 to form chimeric 6HBs. Circular dichroism (CD) and sedimentation equilibrium measurements indicate that the chimeric HeV N42/HPIV3 C33 complex is more stable than the corresponding homotypic HeV complex. Moreover, we show that this chimeric 6HB is stabilized by a glutamic acid 459-to-valine substitution (E459V) in HeV N42/HPIV3 C33. Interestingly, this E459V mutant peptide is a potent inhibitor of HeV/NiV infection, with activity fourfold greater than that of the wild-type (wt) peptide. Thus, the packing interactions of the 6HB are likely to underlie the mechanism of membrane fusion and also provide a good strategy for developing more-potent versions of inhibitory peptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NiV and HeV plaque reduction assay and plaque size assessment.

The effects of peptides on plaque number and size were assessed by a plaque reduction test. Briefly, Vero cells (African green monkey) were seeded into 96-well plates at 2 × 104 cells/200 μl and grown to 90% confluence in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Virus dilutions were chosen to generate 50 to 80 plaques. Peptides were diluted fivefold in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum under biohazard level 4 conditions and were either added prior to the time of infection (see Fig. 1) and removed after 30 min or added after the 30-min adsorption period (see Fig. 2). The cells were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The culture medium was discarded, and plates were immersed in ice-cold absolute methanol for at least 20 min prior to being air dried outside the biohazard level 4 facility. Fixed plates were immunolabeled with anti-P monospecific antisera (28). Briefly, slides were washed in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 5 min. A portion (40 μl) of the anti-P antiserum (1:200 in PBS-BSA) was applied to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Slides were rinsed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and washed for 5 min in PBS-BSA. A portion (40 μl) of the fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit antiserum (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA) diluted 1:100 in PBS-BSA was then applied to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Slides were rinsed again with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and washed for 5 min in PBS-BSA. Wells were overlaid with glycerol-PBS (1:1) containing DABCO (1,4-diazabicyclo[2,2,2]octane) (25 μg/ml) and stored in the dark prior to imaging.

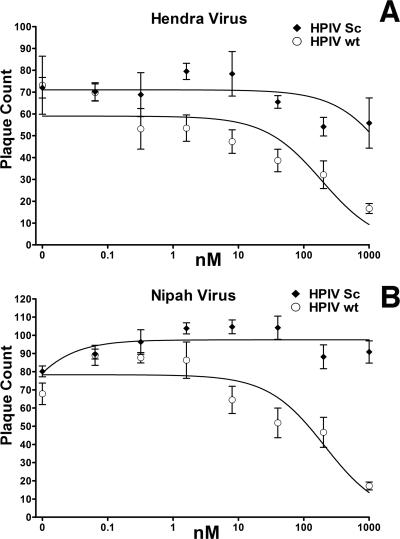

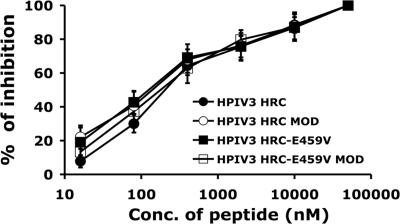

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of HeV and NiV infection by HPIV3 HRC peptides. Vero cell monolayers were infected with 50 to 80 PFU of HeV or NiV in the presence of HPIV wt peptides or HPIV scrambled (sc) peptides at the indicated peptide concentrations (nM). Values are means (±standard deviations; n = 6).

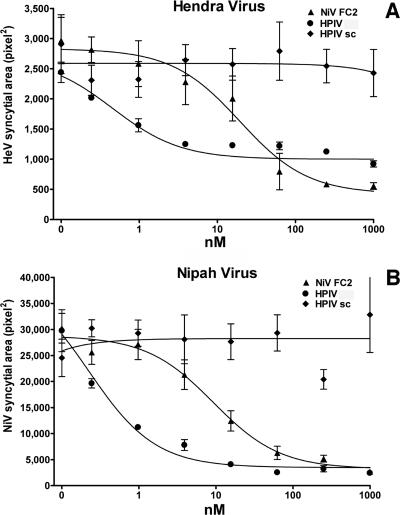

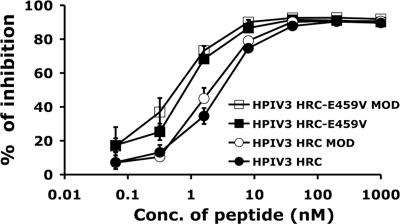

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of HeV and NiV plaque enlargement by HPIV3-derived and NiV-derived peptides. Vero cell monolayers were infected with 50 to 80 PFU of HeV or NiV. At 30 min after infection, HPIV wt peptides, HPIV scrambled (sc) peptides, or NiV-derived peptides (NiV FC2) were added at the indicated concentrations (nM). Plaque size (pixel2) is also shown. Values are means (±standard deviations; n = 6).

Fluorescein isothiocyanate immunofluorescence was visualized using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope (Olympus Australia, Mt. Waverley, Australia) coupled to an Olympus DP70 high-resolution color camera. Image analysis was performed using AnalySIS image analysis software (Soft Imaging System GmbH, Munster, Germany) and enabled the numbers and sizes of plaques in the control and experimental wells to be measured.

Inhibition of henipavirus plaque enlargement of Vero cells was performed as previously described (5). Individual virus syncytia were detected by threshold analysis followed by “hole filling” and subsequently measured to determine the area of each syncytium. To ensure repeatability between images, all procedures were performed as a macro function with fixed parameters. Nine images were analyzed for each peptide concentration, resulting in the collation of syncytial area data for between 8 and 100 foci per peptide concentration (average of ∼50). Measurements were collated and nonlinear regression analysis performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) to determine the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50).

Cells and viruses.

293T (human kidney epithelial) and Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Cellgro; Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics in 5% CO2. The effect of peptides on HPIV3 plaque number was assessed by a plaque reduction test performed as described previously (25). Briefly, CV-1 cell monolayers were inoculated with 100 to 200 PFU of HPIV3 in the presence of various concentrations of peptides. After 90 min, 2× minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was mixed with 1% agarose and added to the dishes. The plates were then inverted and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After removal of the agarose overlay, the cells were immunostained for plaque detection. The numbers of plaques in the control (no peptide or scrambled peptide) and experimental wells were counted under a dissecting stereoscope.

Plasmids and reagents.

HeV wt G and wt F in pCAGGS were a gift from Lin-Fa Wang. To generate the shortened-cytoplasmic-tail variant of HeV G (HeV G-CT32), an internal primer containing an EcoRI site and initiating at position 32 of the open reading frame was used for nested PCR. The primer sequence was 5′ GGAATTCGGCACAATGGACATCAAG 3′.

Transient expression of G and F.

Transfections were performed according to the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent manufacturer protocols (Invitrogen).

HR peptides.

Peptides were synthesized with a Symphony peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, Inc., Massachusetts) by standard 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl-2-(1-H-benzo-triazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) methods, purified to homogeneity by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan), and characterized with a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (aBI Voyager DE; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Peptides were weighed and then completely dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 5 mM, based on the molecular weight provided by the synthesizer. The peptides used in experiments had similar solubility characteristics. All peptides for live-virus inhibition experiments were synthesized by Auspep (Parkville, Australia). The sequence of the NiV-derived peptide (NiV FC2) used in live-virus experiments (5) is KVDISSQISSMNQSLQQSKDYIKEAQRLLDTVNPSL.

Pseudotyped-virus infection assay.

VSV-ΔG-RFP is a recombinant VSV derived from the cDNA of VSV Indiana, in which the G gene is replaced with the Ds-Red (RFP) gene. Pseudotypes with HeV F and G were generated as described previously (32, 43). Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding VSV G, HeV G-CT32/F, HeV G-CT32, or HeV F. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the dishes were washed and infected (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1) with VSV-ΔG-RFP complemented with VSV G. Supernatant fluid containing pseudotyped virus (HeV F/G-CT32 or VSV G) was collected 24 h postinfection and stored at −80°C. For infection assays, HeV F/G-CT32 or VSV G pseudotypes (controls) (data not shown) were used at an MOI of 0.25 to infect Vero cells. Peptides (HRC peptides derived from either HeV F or HPIV3 F) were added at various concentrations. RFP production at 36 h was analyzed by fluorescent microscopy (37) and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson).

Pseudotyped entry assay/mimicking multicycle replication.

HeV glycoproteins were pseudotyped onto a recombinant VSV that expresses RFP but lacks VSV G, and the resulting pseudotyped viruses (VSV-ΔG-RFP-HeV F/G) were used to infect viral glycoprotein-expressing cells for a simulation of multicycle replication. Although this assay simulates multicycle replication, since the cells express the viral glycoproteins and thus can generate more pseudotyped particles if infected, the assay is safe because these particles can replicate only in cells that express HeV G/F. RFP production at 36 h was analyzed by fluorescent microscopy (37) with a microplate fluorescent reader (Spectramax M5).

Protein expression and purification.

The HeV and HPIV3 F HRN/HRC segments (see Fig. 6) were cloned into the pET24a vector (Novagen) to generate the homotypic and chimeric N42(L6)C33 constructs, using standard molecular biology techniques. Substitutions were introduced into pN44(L6)C33 by using the method of Kunkel et al. (21) and verified by DNA sequencing. All recombinant proteins were expressed in the Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen). Cells were lysed by glacial acetic acid and centrifuged to separate the soluble fraction from inclusion bodies. The soluble-fraction-containing protein was subsequently dialyzed into 5% acetic acid overnight at 4°C. All peptide proteins were purified to homogeneity by reverse-phase HPLC (Waters, Inc.) with a Vydac C18 preparative column (Hesperia, CA) using a water-acetonitrile gradient in the presence of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and lyophilized. Protein identities were confirmed by electrospray mass spectrometry (Voyager Elite; PerSeptive Biosystems, Cambridge, MA). Protein concentrations were determined by using the method of Edelhoch (12).

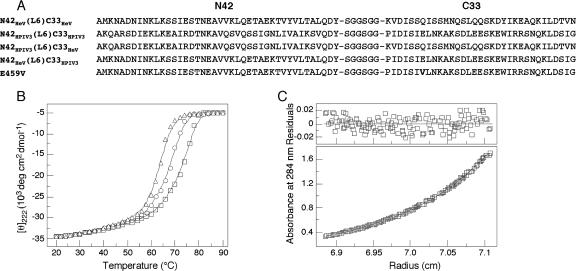

FIG. 6.

Interactions of two hydrophobic HR (HRN and HRC) regions in HeV and HPIV3 F. (A) Amino acid sequences of the N42 and C33 segments of the homotypic and chimeric HRN/HRC constructs. The recombinant N42(L6)C33 peptide consists of the N44 and C33 segments connected by the linker residues Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly. A glutamic acid 459-to-valine mutation is indicated in the E459V sequence. (B) Thermal melts of N42HeV(L6)C33HeV (triangles), N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 (circles), and E459V (squares) constructs, monitored by the CD signal at 222 nm at a 50 μM protein concentration in TBS (pH 8.0) in the presence of 3 M GuHCl, a chemical denaturant. deg, degrees. (C) Sedimentation equilibrium data (19,000 rpm) for the E459V peptide, collected at 20°C in TBS (pH 8.0) at an ∼200 μM protein concentration. The deviation in the data from the linear fit for a trimeric model is plotted (top).

CD spectroscopy.

CD experiments were performed with an Aviv 62A/DS (Aviv Associates, Lakewood, NJ) spectropolarimeter equipped with a thermoelectric temperature control in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and 50 μM protein. CD spectra were collected from 260 to 200 nm at 4°C, using an average time of 5 s, a cell path length of 0.1 cm, and a bandwidth of 1 nm. An ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222) value of −35,000 degrees cm2 dmol−1 was taken to correspond to 100% helix (8). Thermal stability was determined by monitoring [θ]222 as a function of temperature in TBS (pH 8.0) and with the addition of 3 or 5 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) to facilitate unfolding. Thermal melts were performed at 2-degree intervals with a 2-min equilibration at the desired temperature and an integration time of 30 s. Reversibility was verified by repeated scans. Superimposable folding and unfolding curves were observed, and >90% of the signal was regained upon cooling. Values of midpoint unfolding transitions (melting temperature [Tm]) were estimated by evaluating the maximum of the first derivative of [θ]222 versus temperature data (7).

Sedimentation equilibrium analysis.

Analytical ultracentrifugation measurements were carried out with a Beckman XL-A (Beckman Coulter) analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with an An-60 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 20°C. Protein samples were dialyzed overnight against TBS (pH 8.0), loaded at initial concentrations of 20, 60, and 200 μM, and analyzed at rotor speeds of 19,000 and 22,000 rpm. Data were acquired at two wavelengths per rotor speed setting and processed simultaneously with a nonlinear least-squares fitting routine (18). Solvent density and protein partial specific volume were calculated according to solvent and protein composition, respectively (24). Apparent molecular masses were all within 10% of those calculated for an ideal trimer, with no systematic deviation of the residuals.

RESULTS

Peptides corresponding to the HRC region of HeV and HPIV3 F inhibit HeV and NiV infection.

We have shown previously, by using a pseudotyped-HeV entry assay, that an HPIV3 36-amino-acid HRC peptide inhibits infection by pseudotyped HeV (35) more effectively than does a homotypic HeV HRC peptide. In this study, the inhibitory effect of this HPIV3 peptide was assessed by a plaque reduction assay in which we tested the ability of the peptide to interfere with plaque formation by HeV and NiV. We found that this peptide was active in a viral plaque reduction assay, causing a significant inhibition at 8 nM for both viruses (Fig. 1). The plaque number IC50s (concentrations required for a 50% decrease in plaque number), determined from the curves obtained by plotting the percent decrease in plaque number against the log inhibitor concentration, were 179 nM for HeV and 208 nM for NiV. These findings suggest that the reduction in plaque number resulted from interference with viral entry. However, viral entry is not the only process that HRC peptides inhibit. A NiV HRC peptide had previously been shown to reduce syncytium enlargement (5) (the peptide sequence is given in Materials and Methods); however, the peptide was added only after infection. To compare this previously described peptide with our HPIV3 peptide, we carried out a plaque enlargement assay for both HeV and NiV in the presence of either the NiV-derived peptide or the new HPIV3-derived peptide. Based on the IC50s for inhibition of HeV and NiV plaque enlargement (syncytial area) by the two peptides, the HPIV3-derived peptide blocked HeV and NiV 10- to 50-fold more potently than the peptide derived from NiV (Fig. 2), i.e., the HPIV3-derived peptide blocked HeV at 0.45 nM and NiV at 0.25 nM, whereas the FC2 peptide derived from NiV blocked HeV at 4.2 nM and NiV at 11.4 nM (5). At very high concentrations of peptide (50 to 1,000 nM), homologous inhibition appears to be effective and NiV peptides also inhibit HeV infection; however, at peptide concentrations more achievable in the bloodstream (0.5 to 10 nM), this inhibition is far less effective. Scrambled peptides had no effect on viral infection or plaque enlargement. In addition to the reduction in the number of plaques seen with peptide preincubation (Fig. 1), a much greater reduction in plaque size was seen with the plaque enlargement IC50s (concentrations required for a 50% decrease in plaque enlargement), determined from curves obtained by plotting the percent inhibition of plaque size for each peptide concentration (see above). Thus, the HPIV3-derived HRC peptide is effective not only for live HeV but also for live NiV.

Mutation of the effective HPIV3 HRC peptide enhances inhibition of HeV pseudotyped viral entry.

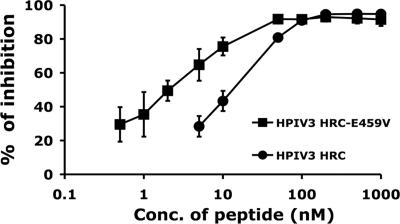

We previously described three mutant HPIV3 HRC peptides (HPIV3-L451N, HPIV3-I484D, and the double mutant HPIV3-L451N+I484D) (35) that were designed based on the crystal structure of the uncleaved posttriggered HPIV3 F protein (Protein Data Bank code 1ztm) (50). The mutations described for these three peptides were localized to the N-terminal and C-terminal segments, regions that appeared to be required for heterotypic activity in the wt HRC peptide (35). We analyzed the average interaction for residues along the whole length of the peptide by using HINT software (35). A high negative score for glutamic acid 459 with chain I, arising from unfavorable hydrophobic-polar interactions, suggested that changing this residue to valine (i.e., E459V) in the corresponding HRC peptide would improve its binding to the HRN chain. In fact, here we found that when the glutamic acid at residue 459 in the peptide is mutated to valine (E459V), it yields the most effective anti-HeV peptide yet tested.

In order to test the effectiveness of the mutated peptide in an assay that reproduces the conditions of viral entry, we employed a virion-based infection assay for HeV that uses the highly effective fusion-promoting G-CT32 protein (35). HeV glycoproteins were pseudotyped onto a recombinant VSV that expresses RFP but lacks its attachment protein, G. The resulting pseudotyped virus, VSV-ΔG-RFP-HeV G-CT32/F, contains the binding and fusion proteins from HeV. Infection of target cells by pseudotyped virus in the absence and presence of HRC peptides was quantified by assessing the production of red fluorescence.

In the experiments shown in Fig. 3, we tested the HPIV3 HRC E459V mutated peptide for its effect on entry of the pseudotyped virus. In the experiment shown, Vero cells were infected with pseudotyped virus at an MOI of 0.25 in the presence of peptides (the parent HPIV3 peptide and the E459V mutated peptide) at various concentrations. At 36 h after infection, entry into the target cells was quantified. The results, showing the enhanced efficacy of the mutated peptide, indicate the importance of the E459V residue for heterotypic inhibitory activity.

FIG. 3.

Inhibitory effects of HRC peptides (wt HPIV3 and the HPIV3 E459V mutated peptide) on infection by HeV G/F pseudotyped viruses. Vero cells were infected with pseudotyped VSV-ΔG-RFP-HeV G-CT32/F virus at an MOI of 0.25 in the presence of increasing concentrations (Conc.) of peptide inhibitors. At 36 h after infection, the number of fluorescent cells was determined using FACS analysis. The results are shown as percent inhibition of viral entry (compared to results for inhibitor-free controls). Values are means (±standard deviations) of results from three separate experiments.

Inhibition of HPIV3 viral entry by mutated HPIV3 HRC peptide.

While the modification at E459 of the HPIV3-derived HRC peptide led to enhancement of inhibitory activity for HeV entry, this mutation had no effect on HPIV3 entry. We tested the mutated peptide in a plaque reduction assay performed as described previously (25). In addition, in this system we tested several modifications that, based on the experience with T-20, we predicted would be useful for enhancing therapeutic potential. We synthesized and tested capped, N-acetylated versions of the parent HPIV3 peptide and the E459V peptide discussed above for Fig. 3 and found the modified peptides to be at least as effective in vitro as the unmodified versions (Fig. 4). Both were HPLC purified, rendering them more effective than the crude preparations we used previously (35); however, note (as shown in Fig. 4) that the mutation conferred no improvement in effectiveness when tested versus the homologous virus.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition by HPIV3 HRC peptides of infection with HPIV3 virions. CV-1 cells were infected with HPIV3 wt virus at an MOI of 6 × 10−4 in the presence and absence of different concentrations (Conc.) of peptides. After 2 h, cells were overlaid with agarose, and plaques were stained at 18 h postinfection. The percent inhibition of viral entry (compared to results for control cells infected in the absence of inhibitors) is shown as a function of the concentration (log scale) of HPIV3 HRC peptide with and without Cap or mutated at position 459 with or without Cap. Data points are means (±standard deviations) of results from three separate experiments. MOD, modified.

Modifications of the effective HPIV3 HRC peptides do not alter inhibitory activity versus HeV.

We tested the capped, N-acetylated versions of the effective peptides discussed above for Fig. 3 and 4 (the HPIV3 36-amino-acid peptide and the E459V peptide) for their anti-HeV activities. Figure 5 shows that these capped, N-acetylated peptides are at least as effective in vitro as the unmodified versions. Both peptides in this experiment were HPLC purified, rendering them 10 times more effective than the crude preparations we used previously (35), which were already superior to previously published candidate peptide inhibitors (NiV FC2 [5]). The experiment shown in Fig. 5 assessed the efficacy of the peptides at inhibiting HeV pseudotyped-virus entry in a new assay that mimics multicycle replication. In this assay, the pseudotyped virus described above for Fig. 3 was used to infect viral glycoprotein-expressing cells for a simulation of multicycle replication; viral particles that bear surface G/F are produced, but this replication can occur only in G/F-expressing cells (further details of this assay are presented elsewhere [P. Carta et al., submitted for publication]). In the experiment shown here, Vero cells transfected with viral glycoproteins (G/F) were infected with pseudotyped virus at an MOI of 0.25 in the presence of peptides (the parent HPIV3 peptide and the E459V mutated peptide) at various concentrations. At 36 h after infection, entry into the target cells in the absence and presence of the original and mutated HRC peptides was quantified by assessing red fluorescence. A major advantage of this strategy for pseudotyped viral entry assays over those previously described for entry assays is that although it simulates multicycle replication, since the cells express the viral glycoproteins and thus can generate more pseudotyped particles if infected, the assay is safe because these particles can replicate only in cells that express HeV G/F, and the resultant viral particles bear the VSV genome.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of HeV pseudotyped-virus infection by modified HPIV3 F HRC peptides, determined by use of an assay that mimics multicycle replication. Vero cells transfected with HeV G and HeV F were infected with pseudotyped VSV-ΔG-RFP-HeV G-CT32/F virus in the presence of HPIV3 HRC and HPIV3 E459V HRC at various concentrations (Conc.), either in modified (N-acetylated and capped) (MOD) or in unmodified form. At 36 h after infection, pseudotyped viral entry was quantified by assessing red fluorescence through FACS analysis. Values are means (±standard deviations) of results from three separate experiments.

The anti-HeV potency of exogenous HPIV3 C peptides correlates with their high binding affinity for the N-peptide coiled coil of HeV.

We hypothesized that the anti-HeV C peptides derived from the HRC of HPIV3 F are likely to act in a dominant-negative manner by binding to the F HRN, thereby disrupting fusogenic trimer-of-hairpin formation and blocking viral entry. To directly test this hypothesis, we compared the abilities of C peptides derived from HeV and HPIV3 to interact with N peptides derived from these two viruses. Based on the published crystal structures of the HeV and NiV F 6HBs (48), we designed and constructed peptides corresponding to the homotypic and chimeric fusion cores of the HeV and HPIV3 F proteins (Fig. 6A). These model polypeptides, designated N42(L6)C33, consist of the N42 and C33 peptides connected via a short peptide linker. The N42(L6)C33 constructs were produced by bacterial expression and purified to homogeneity by reverse-phase HPLC. CD spectroscopy indicates that the recombinant proteins are well folded and contain >90% helical structure in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl (TBS) (Table 1). Analytical ultracentrifugation measurements indicate that each protein exists in a discrete trimeric state over a 10-fold range of protein concentrations (20 to 200 μM). We conclude that the HeV and HPIV3 N42 and C33 peptides can associate to form chimeric trimers of helical hairpins (Table 1; Fig. 6C).

TABLE 1.

Summary of physicochemical analyses

| Construct | [θ]222 (degrees cm2 dmol−1) | Tm (°C) | Tm3M GuHCl (°C)a | Tm5M GuHCl (°C)a | Mobs/Mmonomerb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N42HeV(L6)C33HeV | −34,600 | >100 | 63 | <0 | 2.9 |

| N42HPIV3(L6)C33HPIV3 | −34,800 | >100 | >100 | >95 | 3.0 |

| N42HPIV3(L6)C33HeV | −34,200 | 75 | <0 | <0 | 3.0 |

| N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 | −34,500 | >100 | 67 | <0 | 3.0 |

| E459V | −34,600 | >100 | 72 | <0 | 2.9 |

Tm3M GuHCl, Tm in 3 M GuHCl; Tm5M GuHCl, Tm in 5 M GuHCl. All scans and melts were performed at a 50 μM protein concentration.

Mobs/Mmonomer, apparent molecular mass, determined from sedimentation equilibrium data, divided by the expected mass of a monomer.

The thermal stabilities of the homotypic and chimeric N42(L6)C33 6HBs were assessed using CD by monitoring the ellipticity at 222 nm as a function of temperature at a 50 μM protein concentration in TBS (pH 8.0). N42HeV(L6)C33HeV, N42HPIV3(L6)C33HPIV3, and N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 have thermal stabilities that exceed 100°C, and N42HPIV3(L6)C33HeV exhibits a cooperative melt, with a Tm of 75°C (Table 1). In the presence of the denaturant GuHCl at a 3 M concentration (2, 3), N42HeV(L6)C33HeV and N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 unfold cooperatively, with apparent Tms of 63°C and 67°C, respectively (Fig. 6B; Table 1). On the other hand, N42HPIV3(L6)C33HPIV3 forms an unusually stable helical structure, with an apparent Tm of >95°C in the presence of 5 M GuHCl (Table 1). Taken together, these results indicate that HeV N42 forms a more stable chimeric complex with HPIV3 C33 than with its HeV counterpart.

These data suggest a direct correlation between the anti-HeV potency of exogenous HPIV3 C peptides and their high binding affinity for the N peptide coiled coil of HeV. To test this notion, we introduced the glutamic acid 459-to-valine substitution into the N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 construct to determine the effect of this mutation on the overall structure and stability of the 6HB. CD spectroscopy and sedimentation equilibrium measurements indicate that the E549V mutant forms a trimeric, helical structure that does not unfold upon being heated to 98°C at a 50 μM protein concentration in TBS (pH 8.0) (Table 1; Fig. 6C). This structure unfolds cooperatively, with an apparent Tm of 72°C in the presence of 3 M GuHCl (Fig. 6B), compared to an apparent Tm of 67°C for N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 under the same conditions (Table 1). Thus, the glutamic acid 459-to-valine substitution in the N42HeV(L6)C33HPIV3 construct stabilizes the 6HB conformation.

DISCUSSION

The current hypothesis regarding inhibition by homotypic peptides or other molecular mimics of the HR regions of F is that binding to the HRN and/or HRC region of F can prevent F from achieving its fusion-ready conformation and thereby prevent viral entry. Here we describe HPIV3 heterotypic peptides that are far more effective HeV/NiV inhibitors than the homotypic HeV/NiV peptides.

The helical packing rearrangements triggered by receptor binding are likely to underlie the mechanism of the F structural transitions required for activation of HeV/NiV membrane fusion. Our results show that the propensity of C peptides to form stable 6HBs with the N42 coiled coil may be predictive of inhibitory potency. Mutagenesis studies suggest that the packing interactions between the N and C peptide helices of F are critical for paramyxovirus membrane fusion (41). The conserved Glu459 residue on the buried face of the C peptide helix of HPIV3 F is packed within the interior of the fusion core structure (50). In this study, we demonstrate that the glutamic acid 459-to-valine mutation enhances by fourfold the inhibition by the HPIV3 HRC-derived peptide. We also demonstrate that this enhanced inhibitory activity is likely to reflect structural perturbations that strengthen helical packing interactions with HeV N42 within the 6HB. Thus, the glutamic acid 459-to-valine mutation can impart strong helical character and binding energy to the C peptide for binding to the trimeric coiled coil of HeV F by providing additional hydrophobic packing forces and removing a buried charged side chain.

It is likely that it is not simply the strongest interactions that lead to the most effective inhibitors in vivo. Instead, a balance among specific interactions, solubility, and folding behaviors may determine the in vivo outcome. Biophysical analyses like the experiments performed here will likely reveal the optimal relationships among specific interactions, solubility, and folding behaviors that determine efficacy for therapeutic candidates. Determining the three-dimensional structural basis for interactions between the HR regions will assist anti-HeV/NiV drug development in addition to providing insights into fusion-activating conformational changes in F. We are encouraged by the result that the in vitro potency of the HPIV3 peptide described here is comparable to that of T-20 for HIV-1, a peptide that proved to be clinically efficacious (20).

Why does the mutated HPIV3-derived peptide inhibit HPIV3 infection similarly to the parent HRC peptide? The lack of enhancement may indicate that the HPIV3 F protein has evolved near-optimal interactions within the 6HB of HPIV3. The fact that HeV infection, on the other hand, was inhibited more effectively by the HPIV3 HRC peptide (wt and mutant) may stem from the different kinetics of F activation for the two viruses. We have found that HPIV3 F activation and insertion into the target membrane occur at lower temperatures than for HeV F (data not shown), suggesting that HeV F requires more energy to accomplish the required conformational change and that the kinetics of this change at physiological temperatures may be slower. It was reported recently that a NiV F protein with faster fusion kinetics is less sensitive to homotypic HRC peptide inhibition (1). It is therefore conceivable that the faster fusion kinetics of HPIV3 explains the lower-efficiency homotypic inhibition results. We propose that the kinetic window for F activation is shorter for HPIV3.

Determining the structural basis for interactions between the HR regions should assist anti-HeV/NiV drug development as well as strategies for additional paramyxoviruses and other class I fusion molecules. The parent HPIV3-derived peptides that we recently reported (35), without modifications, demonstrated activities similar to those of the N-pegylated versions of the most effective NiV-derived peptides previously reported (5). The N-pegylated NiV-derived peptides were consistently 10-fold more active than their capped equivalents (5). The HPIV3-derived peptides (wt and scrambled) tested here against HeV and NiV (Fig. 2) are at least 10-fold more active than the equivalent NiV-derived peptides (Table 1). It will be of interest to test an N-pegylated version of the HPIV3 E459V mutated peptide reported here, which is already fourfold more active than the parent HPIV3 peptide (see Results).

Overall, our results indicate that the conserved interhelical packing interactions within the 6HB structure of F play a role in HeV/NiV entry and in its inhibition. Because the interhelical interactions have been shown to account for the broad anti-HIV-1 activity of gp41 C peptides, our results suggest that more-potent analogs of F C peptide inhibitors can be designed for the ability to form a stable complex with the N peptide coiled coil of paramyxovirus F proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI056185 and AI31971 to A.M. from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), by NIH (NIAID) Northeast Center of Excellence for Bio-defense and Emerging Infections Disease Research U54AI057158 Developmental and Innovation Research grants to A.M. and M.L. (Principal Investigator of Center of Excellence grant, W. I. Lipkin), and by a March of Dimes research grant to A.M.

We acknowledge the Northeast Center of Excellence for Bio-defense and Emerging Infections Disease Research Proteomics Core for peptide synthesis and purification. We thank GTx, Inc., for the kind gift of VSV-ΔG-RFP-VSV-G.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, H. C., K. A. Matreyek, C. M. Filone, S. T. Hashimi, E. L. Levroney, O. A. Negrete, A. Bertolotti-Ciarlet, D. Y. Choi, I. McHardy, J. A. Fulcher, S. V. Su, M. C. Wolf, L. Kohatsu, L. G. Baum, and B. Lee. 2006. N-glycans on Nipah virus fusion protein protect against neutralization but reduce membrane fusion and viral entry. J. Virol. 80:4878-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anfinsen, C. B. 1973. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181:223-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arakawa, T., and S. N. Timasheff. 1984. Protein stabilization and destabilization by guanidinium salts. Biochemistry 23:5924-5929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker, K. A., R. E. Dutch, R. A. Lamb, and T. S. Jardetzky. 1999. Structural basis for paramyxovirus-mediated membrane fusion. Mol. Cell 3:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossart, K. N., B. A. Mungall, G. Crameri, L. F. Wang, B. T. Eaton, and C. C. Broder. 2005. Inhibition of Henipavirus fusion and infection by heptad-derived peptides of the Nipah virus fusion glycoprotein. Virol. J. 2:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler, D. 2004. Fatal fruit bat virus sparks epidemics in southern Asia. Nature 429:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantor, C., and P. Schimmel. 1980. Biophysical chemistry, vol. III. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, NY.

- 8.Chen, Y. H., J. T. Yang, and K. H. Chau. 1974. Determination of the helix and beta form of proteins in aqueous solution by circular dichroism. Biochemistry 13:3350-3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua, K. B., W. J. Bellini, P. A. Rota, B. H. Harcourt, A. Tamin, S. K. Lam, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, S. R. Zaki, W. Shieh, C. S. Goldsmith, D. J. Gubler, J. T. Roehrig, B. Eaton, A. R. Gould, J. Olson, H. Field, P. Daniels, A. E. Ling, C. J. Peters, L. J. Anderson, and B. W. Mahy. 2000. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science 288:1432-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colman, P. M., and M. C. Lawrence. 2003. The structural biology of type I viral membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert, D. M., and P. S. Kim. 2001. Design of potent inhibitors of HIV-1 entry from the gp41 N-peptide region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11187-11192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelhoch, H. 1967. Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry 6:1948-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enserink, M. 2004. Emerging infectious diseases. Nipah virus (or a cousin) strikes again. Science 303:1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harcourt, B. H., A. Tamin, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, L. J. Anderson, W. J. Bellini, and P. A. Rota. 2000. Molecular characterization of Nipah virus, a newly emergent paramyxovirus. Virology 271:334-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horvath, C. M., R. G. Paterson, M. A. Shaughnessy, R. Wood, and R. A. Lamb. 1992. Biological activity of paramyxovirus fusion proteins: factors influencing formation of syncytia. J. Virol. 66:4564-4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu, V. P., M. J. Hossain, U. D. Parashar, M. M. Ali, T. G. Ksiazek, I. Kuzmin, M. Niezgoda, C. Rupprecht, J. Bresee, and R. F. Breiman. 2004. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2082-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, X., R. Ray, and R. W. Compans. 1992. Functional interactions between the fusion protein and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase of human parainfluenza viruses. J. Virol. 66:1528-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, M. L., J. J. Correia, D. A. Yphantis, and H. R. Halvorson. 1981. Analysis of data from the analytical ultracentrifuge by nonlinear least-squares techniques. Biophys. J. 36:575-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi, S. B., R. E. Dutch, and R. A. Lamb. 1998. A core trimer of the paramyxovirus fusion protein: parallels to influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp41. Virology 248:20-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilby, J. M., S. Hopkins, T. M. Venetta, B. DiMassimo, G. A. Cloud, J. Y. Lee, L. Alldredge, E. Hunter, D. Lambert, D. Bolognesi, T. Matthews, M. R. Johnson, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and M. S. Saag. 1998. Potent suppression of HIV-1 replication in humans by T-20, a peptide inhibitor of gp41-mediated virus entry. Nat. Med. 4:1302-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunkel, T. A., J. D. Roberts, and R. A. Zakour. 1987. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 154:367-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamb, R. 1993. Paramyxovirus fusion: a hypothesis for changes. Virology 197:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert, D. M., S. Barney, A. L. Lambert, K. Guthrie, R. Medinas, D. E. Davis, T. Bucy, J. Erickson, G. Merutka, and S. R. Petteway, Jr. 1996. Peptides from conserved regions of paramyxovirus fusion (F) proteins are potent inhibitors of viral fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2186-2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laue, T. M., B. D. Shah, T. M. Ridgeway, and S. L. Pelletier. 1992. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins, p. 90-125. In S. E. Harding, A. J. Rowe, and J. C. Horton (ed.), Analytical ultracentrifugation in biochemistry and polymer science. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 25.Levin Perlman, S., M. Jordan, R. Brossmer, O. Greengard, and A. Moscona. 1999. The use of a quantitative fusion assay to evaluate HN-receptor interaction for human parainfluenza virus type 3. Virology 265:57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu, M., S. C. Blacklow, and P. S. Kim. 1995. A trimeric structural domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:1075-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenzie, J. S., and H. E. Field. 2004. Emerging encephalitogenic viruses: lyssaviruses and henipaviruses transmitted by frugivorous bats. Arch. Virol. Suppl. 18:97-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalski, W. P., G. Crameri, L. Wang, B. J. Shiell, and B. Eaton. 2000. The cleavage activation and sites of glycosylation in the fusion protein of Hendra virus. Virus Res. 69:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moscona, A. 2005. Entry of parainfluenza virus into cells as a target for interrupting childhood respiratory disease. J. Clin. Investig. 115:1688-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moscona, A., and R. W. Peluso. 1991. Fusion properties of cells persistently infected with human parainfluenza virus type 3: participation of hemagglutinin-neuraminidase in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 65:2773-2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray, K., P. Selleck, P. Hooper, A. Hyatt, A. Gould, L. Gleeson, H. Westbury, L. Hiley, L. Selvey, B. Rodwell, et al. 1995. A morbillivirus that caused fatal disease in horses and humans. Science 268:94-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Negrete, O. A., E. L. Levroney, H. C. Aguilar, A. Bertolotti-Ciarlet, R. Nazarian, S. Tajyar, and B. Lee. 2005. EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature 436:401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Sullivan, J. D., A. M. Allworth, D. L. Paterson, T. M. Snow, R. Boots, L. J. Gleeson, A. R. Gould, A. D. Hyatt, and J. Bradfield. 1997. Fatal encephalitis due to novel paramyxovirus transmitted from horses. Lancet 349:93-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plemper, R. K., A. S. Lakdawala, K. M. Gernert, J. P. Snyder, and R. W. Compans. 2003. Structural features of paramyxovirus F protein required for fusion initiation. Biochemistry 42:6645-6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porotto, M., L. Doctor, P. Carta, M. Fornabaio, O. Greengard, G. Kellogg, and A. Moscona. 2006. Inhibition of Hendra virus membrane fusion. J. Virol. 80:9837-9849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porotto, M., M. Fornabaio, G. Kellogg, and A. Moscona. 2007. A second receptor binding site on the human parainfluenza 3 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase contributes to activation of the fusion mechanism. J. Virol. 81:3216-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porotto, M., M. Murrell, O. Greengard, M. Lawrence, J. McKimm- Breschkin, and A. Moscona. 2004. Inhibition of parainfluenza type 3 and Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase receptor binding: effect of receptor avidity and steric hindrance at the inhibitor binding sites. J. Virol. 78:13911-13919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porotto, M., M. Murrell, O. Greengard, and A. Moscona. 2003. Triggering of human parainfluenza virus 3 fusion protein (F) by the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) protein: an HN mutation diminishes the rate of F activation and fusion. J. Virol. 77:3647-3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rapaport, D., M. Ovadia, and Y. Shai. 1995. A synthetic peptide corresponding to a conserved heptad repeat domain is a potent inhibitor of Sendai virus-cell fusion: an emerging similarity with functional domains of other viruses. EMBO J. 14:5524-5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell, C. J., T. S. Jardetzky, and R. A. Lamb. 2001. Membrane fusion machines of paramyxoviruses: capture of intermediates of fusion. EMBO J. 20:4024-4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell, C. J., K. L. Kantor, T. S. Jardetzky, and R. A. Lamb. 2003. A dual-functional paramyxovirus F protein regulatory switch segment: activation and membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 163:363-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sergel, T., L. W. McGinnes, M. E. Peeples, and T. G. Morrison. 1993. The attachment function of the Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein can be separated from fusion promotion by mutation. Virology 193:717-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takada, A., C. Robison, H. Goto, A. Sanchez, K. G. Murti, M. A. Whitt, and Y. Kawaoka. 1997. A system for functional analysis of Ebola virus glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14764-14769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, L., B. H. Harcourt, M. Yu, A. Tamin, P. A. Rota, W. J. Bellini, and B. T. Eaton. 2001. Molecular biology of Hendra and Nipah viruses. Microbes Infect. 3:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wild, C., T. Oas, C. McDanal, D. Bolognesi, and T. Matthews. 1992. A synthetic peptide inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication: correlation between solution structure and viral inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10537-10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wild, C. T., D. C. Shugars, T. K. Greenwell, C. B. McDanal, and T. J. Matthews. 1994. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9770-9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wild, T. F., and R. Buckland. 1997. Inhibition of measles virus infection and fusion with peptides corresponding to the leucine zipper region of the fusion protein. J. Gen. Virol. 78:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu, Y., S. Gao, D. K. Cole, J. Zhu, N. Su, H. Wang, G. F. Gao, and Z. Rao. 2004. Basis for fusion inhibition by peptides: analysis of the heptad repeat regions of the fusion proteins from Nipah and Hendra viruses, newly emergent zoonotic paramyxoviruses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315:664-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao, Q., and R. W. Compans. 1996. Peptides corresponding to the heptad repeat sequence of human parainfluenza virus fusion protein are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Virology 223:103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin, H. S., R. G. Paterson, X. Wen, R. A. Lamb, and T. S. Jardetzky. 2005. Structure of the uncleaved ectodomain of the paramyxovirus (hPIV3) fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9288-9293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young, J. K., R. P. Hicks, G. E. Wright, and T. G. Morrison. 1997. Analysis of a peptide inhibitor of paramyxovirus (NDV) fusion using biological assays, NMR, and molecular modeling. Virology 238:291-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Young, J. K., D. Li, M. C. Abramowitz, and T. G. Morrison. 1999. Interaction of peptides with sequences from the Newcastle disease virus fusion protein heptad repeat regions. J. Virol. 73:5945-5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]