Abstract

Study Objectives:

Modafinil is a wake-promoting agent shown to improve wakefulness in patients with excessive sleepiness (hypersomnolence) associated with shift work sleep disorder, obstructive sleep apnea, or narcolepsy. Safety and tolerability data from 6 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies were combined to evaluate modafinil across these different patient populations.

Methods:

One thousand five hundred twenty-nine outpatients received modafinil 200, 300, or 400 mg or placebo once daily for up to 12 weeks. Assessments included recording of adverse events and effects of modafinil on blood pressure/heart rate, electrocardiogram intervals, polysomnography, and clinical laboratory parameters.

Results:

Two hundred seventy-three patients with shift work sleep disorder, 292 with obstructive sleep apnea, and 369 with narcolepsy received modafinil; 567 received placebo. Modafinil was well tolerated versus placebo, with headache (34% vs 23%, respectively), nausea (11% vs 3%), and infection (10% vs 12%) the most common adverse events. Adverse events were similar across all patient groups. Twenty-seven serious adverse events were reported (modafinil, n = 18; placebo, n = 9). In modafinil-treated patients, clinically significant increases in diastolic or systolic blood pressure were infrequent (n = 9 and n = 1, respectively, < 1% of patients). In the studies, 1 patient in the modafinil group and 1 in the placebo group had a clinically significant increase in heart rate. New clinically meaningful electrocardiogram abnormalities were rare with modafinil (n = 2) and placebo (n = 4). Clinically significant abnormalities in mean laboratory parameters were observed in fewer than 1% of modafinil-treated patients at final visit. Modafinil did not affect sleep architecture in any patient population according to polysomnography.

Conclusions:

Modafinil is well tolerated in the treatment of excessive sleepiness associated with disorders of sleep and wakefulness and does not affect cardiovascular or sleep parameters.

Citation:

Roth T; Schwartz JRL; Hirshkowitz M et al. Evaluation of the safety of modafinil for treatment of excessive sleepiness. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3(6):595-602.

Keywords: Excessive sleepiness, hypersomnolence, modafinil, narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, shift work sleep disorder, wake-promoting agent

Excessive sleepiness is a cardinal symptom of many sleep disorders, including shift work sleep disorder (SWSD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and narcolepsy.1,2 SWSD is classified as a circadian rhythm sleep disorder resulting from a sleep-wake pattern that is out of synchrony with the individual's internal biologic rhythm.1 Excessive sleepiness during waking hours is more common in workers on the night shift than in those who regularly work during the day.2 Approximately 45% of night-shift workers have excessive sleepiness, and it often interferes with their activities of daily life.2 SWSD has been estimated to occur in 14% to 32% of night-shift workers.2 Excessive sleepiness also occurs in up to 90% of patients with OSA,3 a sleep disorder caused by frequent arousals from sleep associated with obstruction of airflow through the upper airways.1 Nasal continuous positive airway pressure is the preferred treatment for OSA,4 and it reduces excessive sleepiness5; however, residual excessive sleepiness can persist even with adequate use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure.6 Finally, narcolepsy is a sleep disorder inherently associated with excessive sleepiness. The presence of excessive sleepiness on an almost daily basis is a required diagnostic criterion in patients with narcolepsy, a sleep-wake dysregulation disorder.1 The excessive sleepiness may be accompanied by cataplexy, which is a sudden loss of muscle tone that is typically triggered by strong emotions.1

Excessive sleepiness is associated with impaired cognitive and psychomotor function and diminished quality of life,7 including impaired physical and social functioning, emotional state, and mental health. Typically, individuals with excessive sleepiness have a diminished sense of well-being,8 often with fatigue and reduced energy levels.9,10 There are also significant socioeconomic costs associated with excessive sleepiness. Serious injury and death, costing billions of dollars annually, result from accidents caused by sleepiness.11,12 Excessive sleepiness is also a factor in occupational accidents, and patients with SWSD are more likely to have accidents than daytime workers.2 Job productivity is also lower for shift workers with SWSD than for shift workers without SWSD.2 These adverse economic and public health–related consequences of excessive sleepiness in the general population underscore the need for timely and appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Modafinil, a wake-promoting agent, significantly improves wakefulness in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with SWSD,13,14 OSA,15,16 or narcolepsy.17,18 Objectively and subjectively measured sleepiness decreases in response to modafinil administration. Modafinil differs chemically and pharmacologically from central nervous system stimulants.19,20 Furthermore, modafinil carries lower potential for abuse and adverse cardiovascular events than central nervous system stimulants.21,22 The purpose of this article is to aggregate safety results across studies in disorders of sleep and wakefulness reported previously.13–18 These findings are summarized in the context of the safety and tolerability of modafinil in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with SWSD, OSA, and narcolepsy.

METHODS

Six randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group studies support the efficacy of modafinil for the treatment of adults with excessive sleepiness associated with chronic SWSD,13,14 OSA,15,16 or narcolepsy.17,18 These studies were analyzed to evaluate the overall safety profile of modafinil. In each of these studies, patients met standard diagnostic criteria1 for the respective disorder being investigated and had no other cause of excessive sleepiness. Study protocols were approved by local ethics committees and abided by the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Patients meeting eligibility criteria provided written informed consent before study entry. The 6 studies were conducted at 139 sites in the United States and United Kingdom. The studies were designed by the sponsor and expert specialists in the field of sleep in conjunction with health authorities in each respective country. As per these study designs, the sponsor was responsible for monitoring the analysis of data collected by investigators at each site as well as for data storage and verification. Data were fully accessible to all authors, with the studies' sponsor placing no limits on interpretation or publication. All authors were involved with the preparation of the manuscript.

PATIENTS

Patients at least 18 years of age with a complaint of excessive sleepiness were eligible to participate in each study if they were within the upper age limit for the individual studies (60 years for SWSD, 65 or 70 for OSA, and 65 for narcolepsy). Patients in the 2 SWSD studies were eligible if they had a complaint of excessive sleepiness associated with chronic SWSD. Patients also had to have worked at least 5 night shifts per month (each shift ≤ 12 hours, with ≥ 6 hours of each shift worked between 2200 and 0800), with at least 3 shifts occurring on consecutive nights.13,14 For 1 of the SWSD studies,13 additional criteria included a mean sleep latency of 6 minutes or less on a screening Multiple Sleep Latency Test and a sleep efficiency of 87.5% or less on daytime polysomnography. Patients in the 2 OSA studies must have had residual excessive sleepiness based on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ie, score ≥ 10).15,16 In 1 of the OSA studies, patients had to have residual excessive sleepiness defined as a reduction in the apnea-hypopnea index to less than 10 and a greater than 50% decrease from the historical measurement obtained prior to nasal continuous positive airway pressure use.16 Patients in the 2 narcolepsy studies were eligible if they had a diagnosis of narcolepsy according to The International Classification of Sleep Disorders criteria.23 In addition, objective documentation of sleepiness with the Multiple Sleep Latency Test was required (ie, mean sleep latency ≤ 8 minutes).17,18 Alternate inclusion criteria included a complaint of excessive sleepiness or sudden muscle weakness with associated features (eg, sleep paralysis or hypnogogic hallucinations) and a mean sleep latency of 5 minutes or less.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis or documented primary sleep disorder other than the one for which they were enrolled. Patients with a history of therapeutic failure for excessive sleepiness or any uncontrolled medical disorder were excluded from participation. Additional exclusion criteria included drug sensitivity or drug allergy to stimulant medications and any prior experience with modafinil. Self-reported caffeine consumption was limited to 500 to 900 mg/day or less, depending on the study. Further exclusions included use of any medication with stimulating (eg, methylphenidate, amphetamines) or sedating (eg, sedating antihistamines) properties. Anticataplectic therapy for narcolepsy patients was prohibited. A urine drug toxicology test was performed before administering any study medication. Some concomitant medications, such as analgesics, vitamins, and anti-infectives, were maintained at stable regimens.

Study Design

Studies of SWSD evaluated modafinil taken only when the patient was working a night shift; 1 study13 evaluated modafinil 200 mg, and the other14 evaluated modafinil 200 and 300 mg. In both SWSD studies, dosing occurred 30 to 60 minutes before each regularly scheduled night shift and continued for 12 weeks. Patients were not titrated to the target dose in the SWSD studies and did not take modafinil on days when they were not working. One OSA study15 evaluated modafinil 200 and 400 mg taken once daily in the morning for 12 weeks; the other16 evaluated modafinil 400 mg taken once daily in the morning for 4 weeks. Both narcolepsy studies evaluated modafinil 200 and 400 mg taken once daily in the morning for 9 weeks. Patients in the OSA and narcolepsy studies were titrated to the target dose over a 2- to 9-day period.

Safety Assessments

Assessments included adverse events, vital signs (ie, resting systolic and resting diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, and body weight), electrocardiogram (ECG) intervals, clinical laboratory parameters, and polysomnography during the day (SWSD) or during the night (OSA and narcolepsy studies). All observed and spontaneously reported adverse events were recorded by type and day of onset. Vital signs were monitored at each laboratory visit. Clinically meaningful adverse events specifically associated with blood pressure and heart rate were tabulated on the basis of the frequency of increases in blood pressure or heart rate defined by the Food and Drug Administration. Clinical thresholds for concern were 120 or more beats per minute and an increase of 15 or more beats per minute for heart rate, 180 mm Hg or higher and an increase of 20 mm Hg or more for systolic blood pressure, and 105 mm Hg or higher and an increase of 15 mm Hg or more for diastolic blood pressure. A patient was considered to have a newly diagnosed abnormal ECG finding when ECG was normal at baseline but abnormal at any time after treatment began. ECG data were recorded at baseline prior to modafinil administration and at the final visit using a 12-lead ECG. Physical examinations were conducted at the screening visit and at the last observation of each study. Blood and urine samples were collected at the screening visit, baseline visit, and last observation. Laboratory-attended, comprehensive polysomnography was performed using electroencephalography (central and occipital leads), electrooculography, electromyography (submental and tibialis), ECG, arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation (oximetry), and measures of respiratory flow (nasal and oral) and effort (thoracic and abdominal).

Statistical Analysis

All patients who received at least 1 dose of modafinil or placebo were included in the current analyses. Data were summarized in several ways: (1) by disorder of sleep and wakefulness (ie, SWSD, OSA, or narcolepsy); (2) by treatment group (ie, the dosage a patient was randomly assigned to receive, including once-daily modafinil 200, 300, and 400 mg; all modafinil dosages combined; and placebo); and (3) all studies combined. All analyses were originally specified a priori in the statistical analysis plans. Patient disposition, including investigators' documentation of reasons for discontinuation, was summarized as categorical data for randomized patients.

Demographic data (ie, age, sex, race, and body mass index) were noted among treatment groups at baseline. All reported adverse events were classified by body system and preferred term according to the Coding Symbols for a Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms and summarized as categorical data. Statistical significance between the combined modafinil group and the placebo group for adverse events was determined by Fisher Exact Test. The baseline, final visit, and corresponding change from baseline to final-visit values for vital signs (ie, resting systolic blood pressure, resting diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, and body weight) were summarized as continuous data within study populations (SWSD, OSA, or narcolepsy) and treatment groups. Statistical significance between the combined modafinil group and the placebo group for vital signs was determined by the Wilcoxon Test. The incidences of clinically significant blood-pressure and heart-rate values at any time during treatment were summarized by study population and by treatment group using criteria defined by the Food and Drug Administration and summarized as categorical data.

RESULTS

Patients

In the 6 studies, 1529 patients were randomly assigned to receive either modafinil or placebo (Table 1), with 1501 patients (98%) receiving at least 1 dose of study drug. A total of 1261 patients completed these studies; the percentages of patients completing were similar for all studies (approximately 80%). The overall discontinuation rates were comparable for individuals receiving modafinil (18%) and those receiving placebo (16%). Discontinuation rates were 34% for patients receiving modafinil 300 mg per day, 18% for those receiving 200 mg per day, and 15% for those receiving 400 mg per day. Seventy-eight (8.2%) patients receiving modafinil and 16 (2.8%) patients receiving placebo discontinued because of adverse events. The most frequent adverse event cited as the reason for discontinuation was headache (2%). Nausea, anxiety, dizziness, insomnia, chest pain, and nervousness (each < 1%) were the next most frequent adverse events. Few (≤ 1%) patients discontinued because of lack of efficacy in either group.

Table 1.

Patient Disposition by Treatment Group and Dosea

| SWSD |

OSA |

Narcolepsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | |

| Randomized, no. | 284 | 203 | 295 | 189 | 371 | 187 |

| Safety analysis | 273 (96.1) | 194 (95.6) | 292 (99.0) | 188 (99.5) | 369 (99.5) | 185 (98.9) |

| Completed | 201 (70.8) | 141 (69.5) | 241 (81.7) | 174 (92.1) | 335 (90.3) | 169 (90.4) |

| Discontinued study | 83 (29.2) | 62 (30.5) | 54 (18.3) | 15 (7.9) | 36 (9.7) | 18 (9.6) |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Adverse event | 27 (9.5) | 9 (4.4) | 32 (10.8) | 4 (2.1) | 19 (5.1) | 3 (1.6) |

| Lack of efficacy | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 5 (2.7) |

| Consent withdrawn | 12 (4.2) | 14 (6.9) | 8 (2.7) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (2.4) | 3 (1.6) |

| Protocol violation | 8 (2.8) | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (2.1) | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Noncompliance | 2 (0.7) | 8 (3.9) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.1) |

| Lost to follow-up | 16 (5.6) | 15 (7.4) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 17 (6.0) | 12 (5.9) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Combined | ||||||

| Modafinil |

PL | |||||

| 200 mg | 300 mg | 400 mg | All | |||

| Randomized, no. | 487 | 93 | 370 | 950 | 579 | |

| Safety analysis | 477 (97.9) | 90 (96.8) | 367 (99.2) | 934 (98.3) | 567 (97.9) | |

| Completed | 400 (82.1) | 61 (65.6) | 316 (85.4) | 777 (81.8) | 484 (83.6) | |

| Discontinued study | 87 (17.9) | 32 (34.4) | 54 (14.6) | 173 (18.2) | 95 (16.4) | |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Adverse event | 26 (5.3) | 18 (19.4) | 34 (9.2) | 78 (8.2) | 16 (2.8) | |

| Lack of efficacy | 4 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.5) | 6 (1.0) | |

| Consent withdrawn | 13 (2.7) | 3 (3.2) | 13 (3.5) | 29 (3.1) | 19 (3.3) | |

| Protocol violation | 9 (1.8) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) | 13 (1.4) | 10 (1.7) | |

| Noncompliance | 4 (0.8) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (0.5) | 8 (0.8) | 12 (2.1) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 16 (3.3) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 19 (2.0) | 16 (2.8) | |

| Other | 15 (3.1) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (0.8) | 21 (2.2) | 16 (2.8) | |

All values are number (%) except where indicated otherwise. OSA refers to obstructive sleep apnea; PL, placebo; SWSD, shift work sleep disorder.

A total of 934 patients received modafinil treatment (200 mg, n = 477; 300 mg, n = 90; 400 mg, n = 367), and 567 patients received placebo. Approximately 60% of patients were men, and approximately 80% were white (Table 2). In the OSA studies, with a 76% male enrollment, patients had a mean baseline body mass index of greater than 36 kg/m2. The average duration of modafinil treatment was 42.3 days in patients with SWSD, 65.0 days in patients with OSA, and 60.0 days in patients with narcolepsy.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| SWSD |

OSA |

Narcolepsy |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | |

| Age, ya | 39.2 (9.4) | 39.3 (9.0) | 48.7 (9.2) | 50.6 (9.6) | 42.0 (13.4) | 41.3 (13.2) |

| Menb | 145 (53) | 105 (54) | 229 (78) | 139 (74) | 168 (46) | 85 (46) |

| Raceb | ||||||

| White | 196 (72) | 132 (68) | 257 (88) | 166 (88) | 301 (82) | 154 (83) |

| Other | 77 (28) | 62 (32) | 35 (12) | 22 (12) | 68 (18) | 31 (17) |

| BMI, kg/m2a | 30.2 (6.7) | 30.8 (6.3) | 36.1 (7.6) | 36.2 (8.0) | 28.9 (6.4) | 28.3 (6.1) |

| Combined | Modafinil |

PL | ||||

| 200 mg | 300 mg | 400 mg | All | |||

| Age, ya | 41.7 (11.7) | 40.2 (9.7) | 46.1 (11.8) | 43.3 (11.8) | 43.7 (11.8) | |

| Menb | 277 (58) | 43 (48) | 222 (60) | 542 (58) | 329 (58) | |

| Raceb | ||||||

| White | 374 (78) | 67 (74) | 313 (85) | 754 (81) | 452 (80) | |

| Other | 103 (22) | 23 (26) | 54 (15) | 180 (19) | 115 (20) | |

| BMI, kg/m2a | 31.3 (7.6) | 29.8 (6.6) | 32.7 (7.9) | 31.7 (7.7) | 32.0 (7.9) | |

Data are presented as mean (SD).

Data are presented as number (%).

BMI refers to body mass index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PL, placebo; SWSD, shift work sleep disorder.

Adverse Events

Headache was the most frequently reported adverse event in these studies (Table 3). Most (nearly 90%) adverse events occurred during the first 4 weeks of treatment and were graded as mild to moderate. The overall incidence of adverse events was similar among the 3 modafinil dosage groups. The most common adverse event reported by patients receiving modafinil was headache (modafinil, n = 319 [34%]; placebo, n = 133 [23%]). A dose-related trend was seen only for headache (200 mg, 32%; 300 mg, 26%; 400 mg, 40%; p < .05 vs placebo). Other leading events included nausea (modafinil, n = 107 [11%]; placebo, n = 19 [3%]) and infection (modafinil, n = 97 [10%]; placebo, n = 68 [12%]). Adverse events occurring more frequently in the modafinil group than in controls included headache, nausea, dry mouth, anorexia, nervousness, insomnia, anxiety, hypertension, and pharyngitis. The cumulative incidence of headache for modafinil was 20% at 1 week, 29% at 1 month, and 34% at 3 months. For placebo, the cumulative incidence of headache was 9% at 1 week, 18% at 1 month, and 23% at 3 months. The cumulative incidence of nausea for modafinil was 7% at 1 week, 10% at 1 month, and 11% at 3 months. For placebo, the cumulative incidence of nausea was 2% at 1 week and 3% at 1 month and at 3 months.

Table 3.

Adverse Events Reported by 5% or More of Patientsa

| Adverse Event | SWSD |

OSA |

Narcolepsy |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | |

| n = 273 | n = 194 | n = 292 | n = 188 | n = 369 | n = 185 | n = 934 | n = 567 | |

| Headache | 63 (23) | 37 (19) | 73 (25)b | 22 (12) | 183 (50)b | 74 (40) | 319 (34)b | 133 (23) |

| Nausea | 31 (11)b | 7 (4) | 29 (10)b | 5 (3) | 47 (13)b | 7 (4) | 107 (11)b | 19 (3) |

| Infection | 12 (4) | 14 (7) | 34 (12) | 25 (13) | 51 (14) | 29 (16) | 97 (10) | 68 (12) |

| Nervousness | 18 (7)b | 3 (2) | 21 (7)b | 4 (2) | 30 (8) | 12 (6) | 69 (7)b | 19 (3) |

| Rhinitis | 9 (3) | 9 (5) | 18 (6) | 10 (5) | 42 (11) | 14 (8) | 69 (7) | 33 (6) |

| Back pain | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 9 (3) | 7 (4) | 35 (9) | 16 (9) | 52 (6) | 26 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 12 (4) | 8 (4) | 16 (5) | 10 (5) | 30 (8) | 8 (4) | 58 (6) | 26 (5) |

| Anxiety | 8 (3) | 1 (<1) | 23 (8)b | 3 (2) | 13 (4)b | 1 (<1) | 44 (5)b | 5 (<1) |

| Dizziness | 8 (3) | 7 (4) | 18 (6) | 6 (3) | 17 (5) | 7 (4) | 43 (5) | 20 (4) |

| Dyspepsia | 10 (4) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) | 4 (2) | 26 (7) | 14 (8) | 44 (5) | 21 (4) |

| Insomnia | 18 (7)b | 2 (1) | 16 (5)b | 2 (1) | 11 (3) | 2 (1) | 45 (5)b | 6 (1) |

| Anorexia | 10 (4)b | 1 (<1) | 8 (3) | 3 (2) | 17 (5)b | 2 (1) | 35 (4)b | 6 (1) |

| Dry mouth | 9 (3) | 5 (3) | 9 (3) | 3 (2) | 19 (5)b | 1 (<1) | 37 (4)b | 9 (2) |

| Influenza syndrome | 14 (5) | 5 (3) | 10 (3) | 5 (3) | 13 (4) | 7 (4) | 37 (4) | 17 (3) |

| Pharyngitis | 11 (4) | 7 (4) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 23 (6) | 5 (3) | 39 (4) | 14 (2) |

| Accidental injury | 12 (4) | 9 (5) | 15 (5) | 9 (5) | 3 (<1)b | 12 (6) | 30 (3) | 30 (5) |

| Hypertension | 10 (4)b | 0 (0) | 14 (5) | 3 (2) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 30 (3)b | 3 (<1) |

OSA refers to obstructive sleep apnea; PL, placebo; SWSD, shift work sleep disorder.

Values are presented as number (SD).

p < .05 vs placebo.

In patients taking modafinil, 18 serious adverse events occurred. In the placebo group, there were 9 serious adverse events. Seven adverse events were considered treatment related; these included chest pain, leukopenia, abnormal liver enzymes, extrasystoles, palpitations, dyspnea, and hypoventilation.

Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, and Body Weight

There were no significant changes from baseline to final visit in mean heart rate, systolic blood pressure, or diastolic blood pressure between the modafinil and placebo groups for the SWSD or OSA studies. In the narcolepsy studies, the mean change from baseline to final visit in heart rate and systolic blood pressure was statistically significant between the modafinil and the placebo groups (p < .05; Table 4). These differences were due to a greater change from baseline in the placebo group (mean ± SD: heart rate, −0.8 ± 9.8 beats/min; systolic blood pressure, −3.1 ± 13.0 mm Hg) than in the modafinil group (mean ± SD: heart rate, 0.1 ± 11.7 beats/min; systolic blood pressure, −1.3 ± 13.5 mm Hg). Overall, clinically significant abnormalities in blood pressure and heart rate were rare in both groups regardless of the clinical population (≤ 1% of patients in most cases; Table 5). Clinically significant elevations in diastolic blood pressure (≥ 105 mm Hg and an increase from baseline ≥ 15 mm Hg) were observed in 9 (< 1%) patients who received modafinil and in none of the patients who received placebo; 5 of these 9 patients had a diagnosis of OSA. The initiation or increase in dose of antihypertensive medication was 2.4% in modafinil-treated patients and 0.7% in those receiving placebo. When only OSA studies were included, alterations in use of antihypertensive medications were required for 3.4% of modafinil-treated patients and for 1.1% of patients receiving placebo.

Table 4.

Mean Heart Rate, Systolic Blood Pressure, Diastolic Blood Pressure, and Body Weight at Baseline and Final Visit for Each Disordera

| SWSD |

OSA |

Narcolepsy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | ||

| Parameter | Time Point | n = 273 | n = 194 | n = 292 | n = 188 | n = 369 | n = 185 |

| Heart rate, bpm | Baseline | 71.1 (9.9) | 69.9 (8.8) | 72.4 (10.2) | 71.1 (9.9) | 75.3 (11.4) | 74.1 (11.0) |

| Final visit | 71.5 (10.3) | 70.3 (9.9) | 72.2 (10.0) | 71.3 (10.8) | 75.4 (10.4)b | 73.3 (10.4) | |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||||

| Systolic | Baseline | 122.6 (13.1) | 121.9 (12.3) | 126.9 (12.7) | 129.5 (12.3) | 122.5 (16.4) | 121.0 (15.4) |

| Final visit | 123.9 (13.3) | 123.3 (13.8) | 126.6 (12.7) | 127.4 (12.3) | 121.3 (15.5)b | 118.0 (15.4) | |

| Diastolic | Baseline | 77.9 (9.6) | 79.0 (9.1) | 80.0 (8.0) | 80.4 (8.3) | 76.0 (10.6) | 75.5 (9.9) |

| Final visit | 77.9 (9.8) | 78.4 (8.9) | 79.3 (8.5) | 78.8 (8.4) | 75.4 (10.7) | 74.6 (10.2) | |

| Body weight, kg | Baseline | 89.6 (20.9) | 87.3 (16.8) | 109.7 (22.8) | 109.7 (24.2) | 84.2 (19.6) | 83.2 (19.2) |

| Final visit | 88.6 (21.0) | 87.3 (16.9) | 108.8 (23.4) | 109.9 (24.2) | 83.9 (19.6) | 84.2 (19.3) | |

bpm refers to beats per minute; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PL, placebo; SWSD, shift work sleep disorder.

All values are number (SD).

p < .05 vs placebo.

Table 5.

Clinically Significant Abnormal Values in Vital Signs Based on Prespecified Criteriaa

| SWSD |

OSA |

Narcolepsy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | Modafinil | PL | ||

| Variable | Criteria | n = 273 | n = 194 | n = 292 | n = 188 | n = 369 | n = 185 |

| Heart rate, bpm | ≥ 120 and increase ≥ 15 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| ≤ 50 and decrease ≥ 15 | 2 (<1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (<1) | 4 (2) | |

| SBP, mm Hg | ≥ 180 and increase ≥ 20 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ≤ 90 and decrease ≥ 20 | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| DBP, mm Hg | ≥ 105 and increase ≥ 15 | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| ≤ 50 and decrease ≥ 15 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Body weight (kg) | Increase ≥ 7% | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 5 (3) |

| Decrease ≥ 7% | 2 (<1) | 3 (2) | 20 (7) | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | |

bpm refers to beats per minute; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PL, placebo; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SWSD, shift work sleep disorder.

All values are number (%).

Regardless of patient group, there were no significant changes from baseline in mean body weight (Table 4). Nonetheless, clinically significant decreases in body weight (defined as ≥ 7% decrease from baseline) were reported for 28 (3%) patients receiving modafinil (Table 5). Weight loss was more common in the OSA studies, with clinically significant decreases reported for 20 (7%) patients in the modafinil group. Clinically significant weight loss was seen in 7 (1%) placebo patients across all studies and in 2 (1%) placebo patients in the OSA studies.

Electrocardiogram

Modafinil was similar to placebo in terms of clinically significant ECG changes, and there was no treatment-emergent pattern of ECG abnormalities. Newly diagnosed abnormal ECG findings were reported in 162 (17%) of 934 patients receiving modafinil and 102 (18%) of 567 patients receiving placebo. Of these, only 2 (< 1%) patients receiving modafinil and 4 (< 1%) patients receiving placebo had ECG results that met a priori criteria for clinical significance. All 6 of these patients were enrolled in the OSA studies.

Clinical Laboratory Parameters

In patients with narcolepsy, mean ± SD gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase plasma levels were 36.6 ± 37.44 and 78.4 ± 21.82 U/L, respectively, following administration of modafinil and 25.9 ± 20.98 and 77.3 ± 21.08 U/L, respectively, for placebo; however, fewer than 1% of all elevations were higher than 3 times the upper limit of normal. In patients with SWSD, mean GGT and alkaline phosphatase levels increased following administration of either modafinil or placebo. GGT levels were not measured in patients with OSA; however, alkaline phosphatase levels increased following modafinil administration and decreased with placebo. Clinically significant abnormalities in alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase (> 3 times the upper limit of normal24,25), blood urea nitrogen (≥ 10.71 mmol/L), creatinine (≥ 177 μmol/L), uric acid (men, ≥ 625 μmol/L; women, ≥ 506 μmol/L), and total bilirubin (≥ 34.2 μmol/L) were infrequent (observed in < 1% of patients for all parameters), without treatment-emergent bias toward active drug.

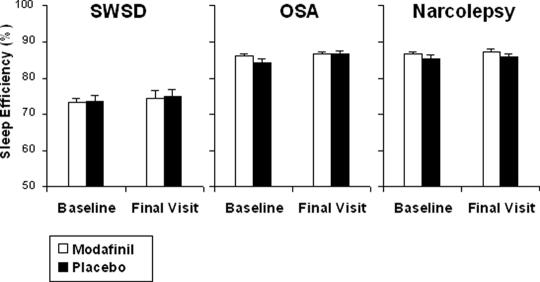

Effects on Desired Sleep

Polysomnography indicated that modafinil had no adverse effect on patients' sleep architecture (Figure 1). No clinically significant difference for sleep efficiency emerged between modafinil and placebo for all 3 patient populations (SWSD, p = .85; OSA, p = .11; narcolepsy, p = .11).

Figure.

Mean ± SEM in sleep efficiency (time asleep as a percentage of the total time in bed) at baseline and final visit as determined by polysomnography. Differences between the modafinil and placebo groups were not statistically significant for any indication (shift work sleep disorder [SWSD], p = .85; obstructive sleep apnea [OSA], p = .11; narcolepsy, p = .11).

DISCUSSION

Data from these 6 studies (2 SWSD, 2 OSA, and 2 narcolepsy) show that modafinil 200, 300, or 400 mg once daily is well tolerated in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with disorders of sleep and wakefulness. Headache and nausea were the most common adverse events observed in patients receiving modafinil. The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate in nature, and only headache was associated with a dose-related effect. Moreover, modafinil was not associated with clinically significant changes in mean vital signs, ECGs, or sleep when sleep was desired. At final visit, elevations in mean GGT and/or alkaline phosphatase were observed in patients receiving modafinil but not in those receiving placebo. Clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory parameters were rare and reported in fewer than 1% of patients receiving modafinil or placebo.

Excessive sleepiness is a common symptom of patients seen by both primary care and specialty medicine physicians.9 A survey conducted by the National Sleep Foundation indicated that 37% of adults (18–54 years old) report that excessive sleepiness interferes with their daily activities at least some of the time, and 16% report that it interferes a few days or more per week.26 Excessive sleepiness may have potentially serious physiological consequences, especially in patients with OSA who have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease.27 Results from a prospective population-based study show a greater than 2-fold increase in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in OSA patients with excessive sleepiness, even after controlling for hypertension and cardiovascular disease.28 There is also evidence that shift workers with repeated disturbances in circadian rhythms experience a negative impact on performance, quality of life, and health, with an increased risk for peptic ulcers and cardiovascular disease.2,29,30 Importantly, in the current analysis, modafinil did not elevate mean blood pressure or heart rate more than did placebo in a population of patients at risk for cardiovascular events (eg, patients with OSA).

Reduced sleep efficiency in patients with SWSD likely results from insomnia and disturbed sleep and is presumably related to work-dictated sleep schedules placed in opposition to patients' internal circadian sleep-wake cycles. Excessive sleepiness in patients with SWSD has been associated with impaired performance and lower job productivity, increased absenteeism, and more accidents than in daytime workers.2 Modafinil has been shown to improve alertness in patients diagnosed with SWSD with a favorable safety profile.

One of the main limitations of these results relates to the short duration (4–12 weeks) of the 6 studies. However, modafinil has been well tolerated during long-term open-label studies of patients with narcolepsy.31,32 Adverse events in these open-label studies were consistent with those observed in the double-blind clinical studies and were mild to moderate in nature. Additionally, no clinically meaningful changes in vital signs or ECGs were found.31,33,34

Modafinil taken in the morning or at the beginning of a night shift does not adversely affect subsequent sleep occurring 8 to 16 hours later.13–18,35 The favorable safety profile of modafinil may, in part, be due to its selective action in the sleep-wake brain centers,19 rather than widespread central nervous system stimulation via dopaminergic pathways. In contrast to traditional nervous system stimulants, the abuse potential for modafinil is considered low, and clinical evidence for the development of dependence or tolerance has not been found.21,36,37

In conclusion, modafinil is well tolerated. Furthermore, it appears from these 6 prospective research studies that daily modafinil administration confers a low risk of adverse events or severe adverse events. These results make for a positive risk-benefit ratio for using modafinil to treat excessive sleepiness in patients with SWSD, OSA, and narcolepsy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was sponsored by Cephalon, Inc., Frazer, PA. The authors wish to acknowledge Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein, MD, for his contribution to analysis of the data for cardiovascular parameters.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The study was supported by Cephalon, Inc., Frazer, PA. Dr. Roth has received research support from Aventis, Cephalon, Glaxo-SmithKline, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, SchoeringPlough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Wyeth, and Xenoport; is a consultant for Abbott, Accadia, Acoglix, Actelion, Alchemers, Alza, Ancil, Arena, AstraZeneca, Aventis, BMS, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Hypnion, Jazz, Johnson – Johnson, King, Ludbeck, Mc-Neil, MedicNova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Orginer, Prestwick, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Restiva, Roche, Sanofi, ShoeringPlough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Vanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport; and has participated in speaking engagements supported by Sanofi and Takeda. Dr. Schwartz has received research support from AstraZeneca, Cephalon, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Neurogen, and ShoeringPlough; has consulted for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Pfizer, ShoeringPlough, Takeda, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and is on the speaker's bureau for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cephalon, Sepracor, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Pfizer, ShoeringPlough, and Takeda. Dr. Hirshkowitz's sleep disorders and research center has been paid for work underwritten by Sanofi, Takeda, Merck, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Cephalon, Sepracor, Respironics, ResMed, and NBI; and is a consultant for and on the speaker's bureau of Sanofi, Takeda, and Cephalon. Dr. Erman has received research support from Sanofi, Mallinckrodt, Cephalon, Takeda, Aventis, Pfizer, Pharmacia, ResMed, Merck, Schwarz, Organon, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Eli Lilly, and Arena; has consulted for Sanofi, Cephalon, Takeda, and Neurocrine; is in the speakers bureau for Sanofi, Forest, and Takeda; and has financial interests in Cephalon, Forest, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sepracor, Merck, and Sanofi. Drs. Dayno and Arora are employees of Cephalon, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep. 2004;27:1453–1462. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seneviratne U, Puvanendran K. Excessive daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea: prevalence, severity, and predictors. Sleep Med. 2004;5:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loube D, Gay P, Strohl K, Pack A, White D, Collop N. Indications for positive airway pressure treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: a consensus statement. Chest. 1999;115:863–866. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engleman HM, Martin SE, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on daytime function in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet. 1994;343:572–575. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91522-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sforza E, Krieger J. Daytime sleepiness after long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1992;110:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(92)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reimer MA, Flemons WW. Quality of life in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:335–349. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin CM, Griffith KA, Nieto FJ, O'Connor GT, Walsleben JA, Redline S. The association of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep symptoms with quality of life in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2001;24:96–105. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pigeon WR, Sateia MJ, Ferguson RJ. Distinguishing between excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue: toward improved detection and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorpy MJ. Which clinical conditions are responsible for impaired alertness? Sleep Med. 2005;6(suppl 1):S13–20. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(05)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leger D. The cost of sleep-related accidents: a report for the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. Sleep. 1994;17:84–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webb WB. The cost of sleep-related accidents: a reanalysis. Sleep. 1995;18:276–280. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czeisler C, Walsh J, Roth T, et al. Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift work sleep disorder. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:476–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.for the Modafinil in Shift Work Sleep Disorder Study Group. Rosenberg R, Erman M, Emsellem H, Niebler G, Wyatt-Knowles E. Modafinil improves quality of life and is well tolerated in shift work sleep disorder. Sleep. 2003;26:A112–A113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black J, Hirshkowitz M. Modafinil for treatment of residual excessive sleepiness in nasal continuous positive airway pressure-treated obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Sleep. 2005;28:464–471. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pack AI, Black JE, Schwartz JR, Matheson JK. Modafinil as adjunct therapy for daytime sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1675–1681. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2103032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Modafinil in Narcolepsy Multicenter Study Group. Randomized trial of modafinil for the treatment of pathological somnolence in narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:88–97. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Modafinil in Narcolepsy Multicenter Study Group. Randomized trial of modafinil as a treatment for the excessive daytime somnolence of narcolepsy. Neurology. 2000;54:1166–1175. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JS, Hou Y, Jouvet M. Potential brain neuronal targets for amphetamine-, methylphenidate-, and modafinil-induced wakefulness, evidenced by c-fos immunocytochemistry in the cat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14128–14133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saper CB, Scammell TE. Modafinil: a drug in search of a mechanism. Sleep. 2004;27:11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myrick H, Malcolm R, Taylor B, LaRowe S. Modafinil: preclinical, clinical, and post-marketing surveillance—a review of abuse liability issues. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:101–109. doi: 10.1080/10401230490453743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz JR. Modafinil: new indications for wake promotion. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:115–129. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2001. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockville, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 1987. Feb 27, Supplementary suggestions for preparing an integrated summary of safety information in an original NDA submission and for organizing information in periodic safety updates. [Google Scholar]

- 25.PhRMA/FDA/AASLD drug-induced hepatotoxicity white paper: postmarketing considerations. [Accessed: February 15, 2007]; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/livertox/postmarket.pdf.

- 26.National Sleep Foundation. “Sleep in America” Poll. [Accessed: April 12, 2006];2002 http://www.kintera.org/atf/cf/%7BF6BF2668-A1B4-4FE8-8D1A-A5D39340D9CB%7D/2002SleepInAmericaPoll.pdf.

- 27.Javaheri S. Sleep and cardiovascular disease: present and future. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 1157–1160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindberg E, Janson C, Svardsudd K, Gislason T, Hetta J, Boman G. Increased mortality among sleepy snorers: a prospective population based study. Thorax. 1998;53:631–637. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.8.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knutsson A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2003;53:103–108. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqg048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puca FM, Perrucci S, Prudenzano MP, et al. Quality of life in shift work syndrome. Funct Neurol. 1996;11:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitler MM, Harsh J, Hirshkowitz M, Guilleminault C. Long-term efficacy and safety of modafinil (PROVIGIL®) for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2000;1:231–243. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moldofsky H, Broughton RJ, Hill JD. A randomized trial of the long-term, continued efficacy and safety of modafinil in narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2000;1:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.for the Modafinil in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Study Group. Schwartz JRL, Bogan RK, Hirshkowitz M. Tolerability, safety, and efficacy of adjunct modafinil in OSA: a 12-month open-label extension study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A900. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenberg RP, Corser B. Patient functional status, safety, and tolerability of modafinil in a 12-month, open-label study in patients with chronic shift work sleep disorder. Sleep. 2004;27:A57–5A8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broughton RJ, Fleming JA, George CF, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of modafinil in the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy. Neurology. 1997;49:444–451. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jasinski DR. An evaluation of the abuse potential of modafinil using methylphenidate as a reference. J Psychopharmacol. 2000;14:53–60. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jasinski DR, Kovacevic-Ristanovic R. Evaluation of the abuse liability of modafinil and other drugs for excessive daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2000;23:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]