Abstract

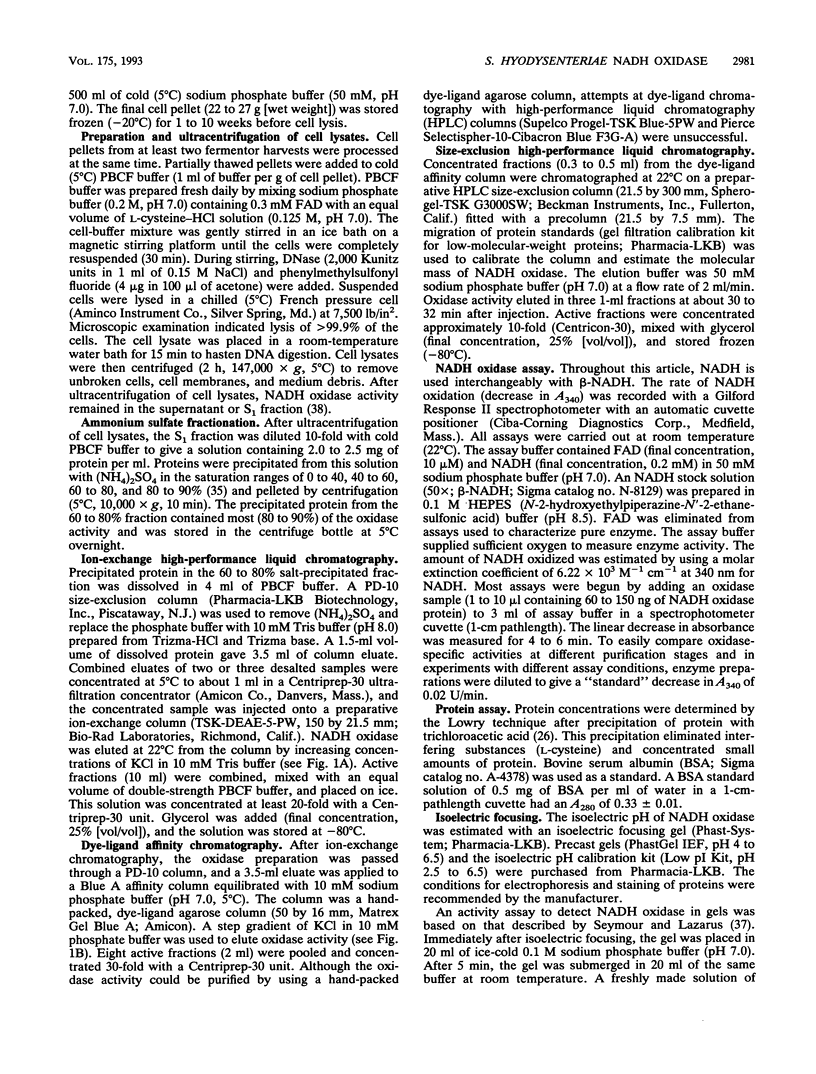

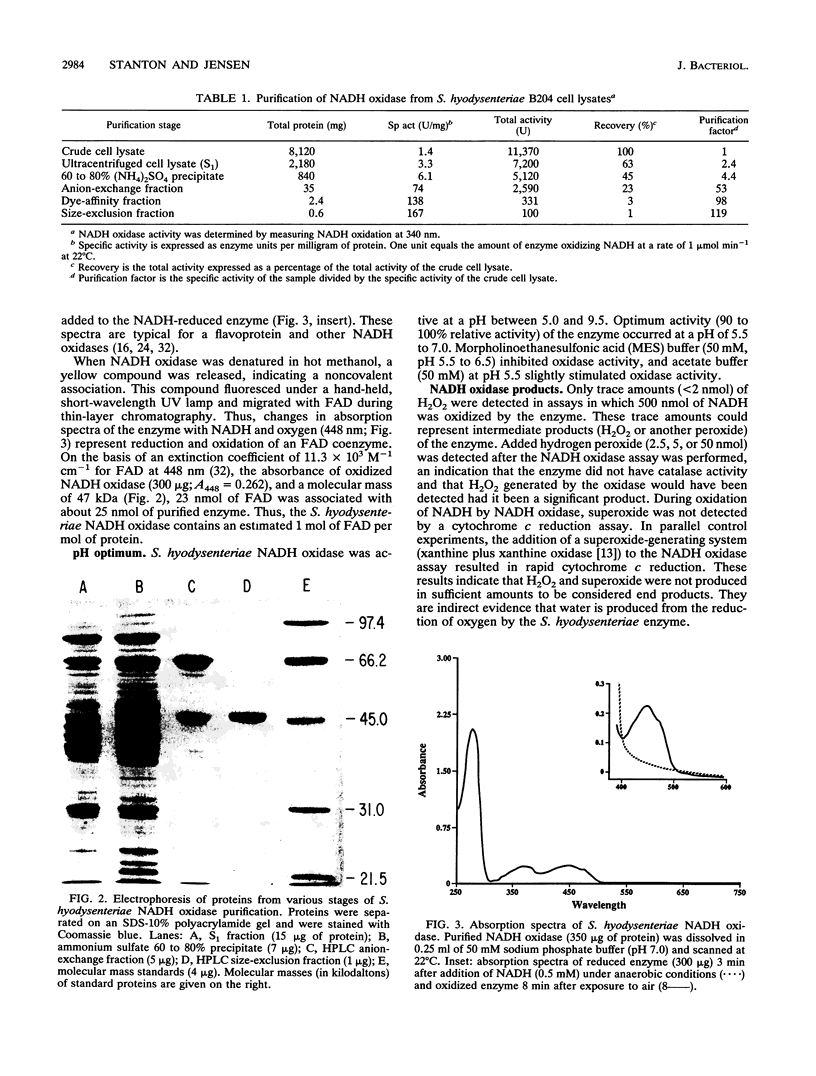

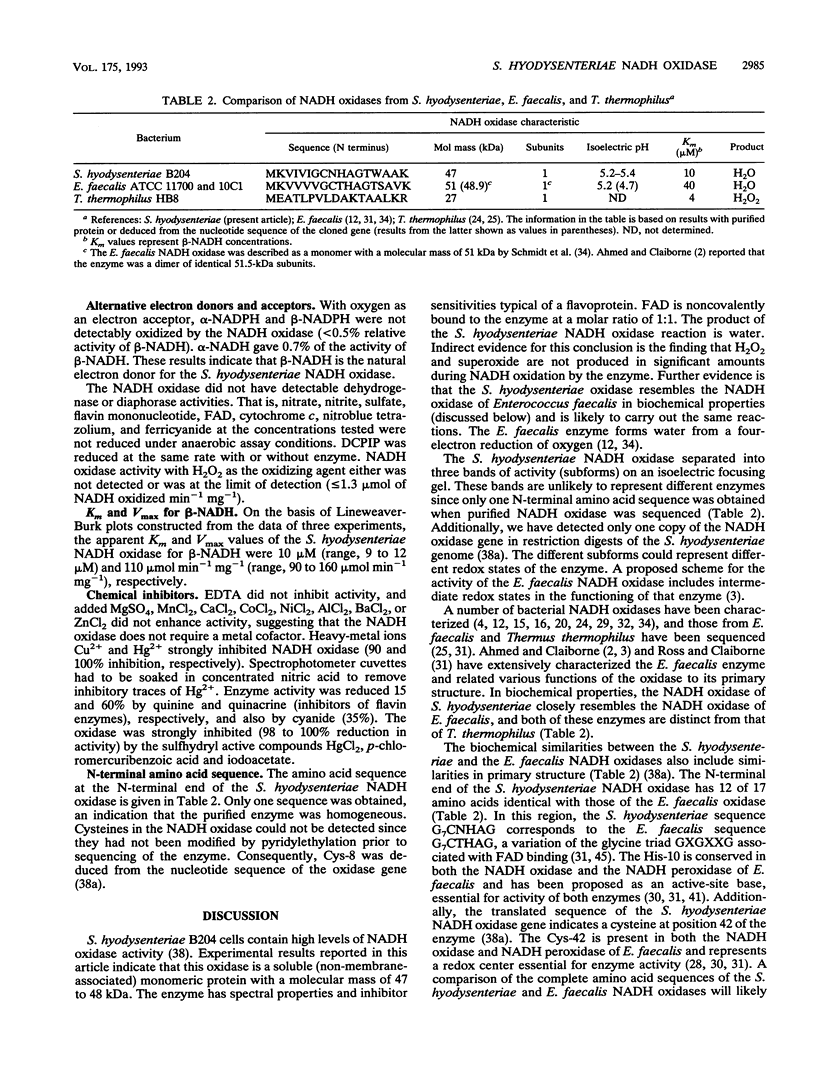

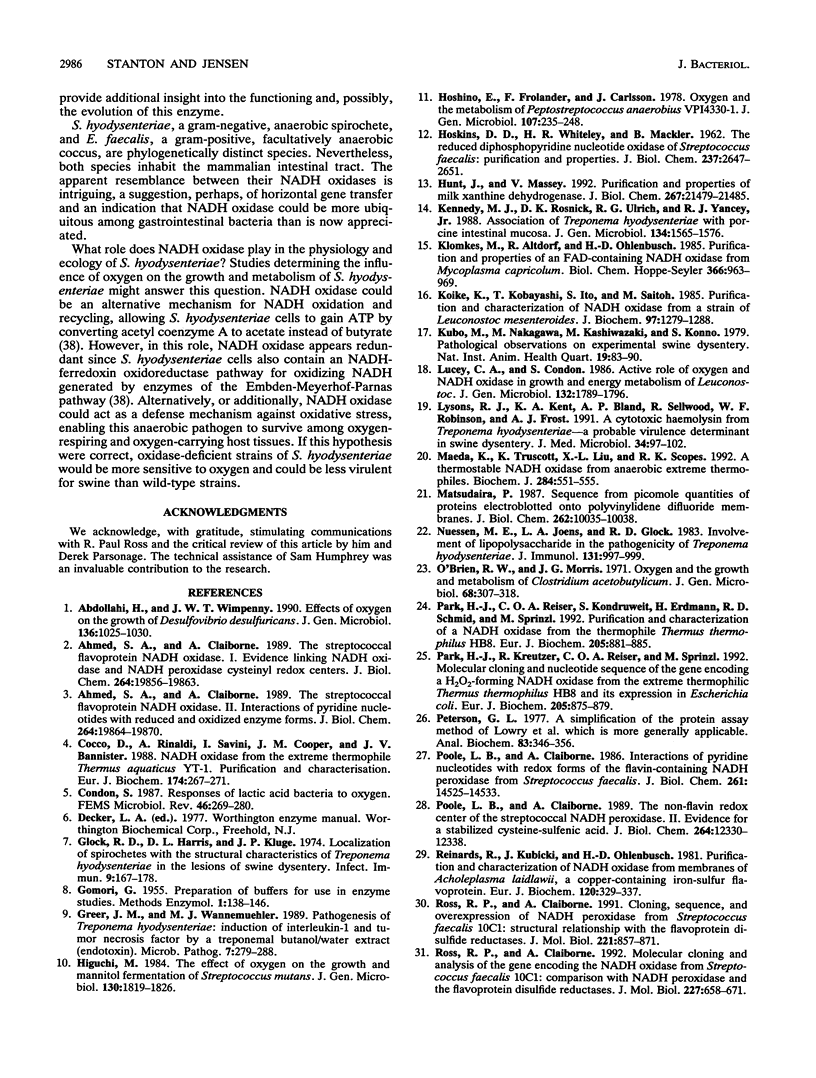

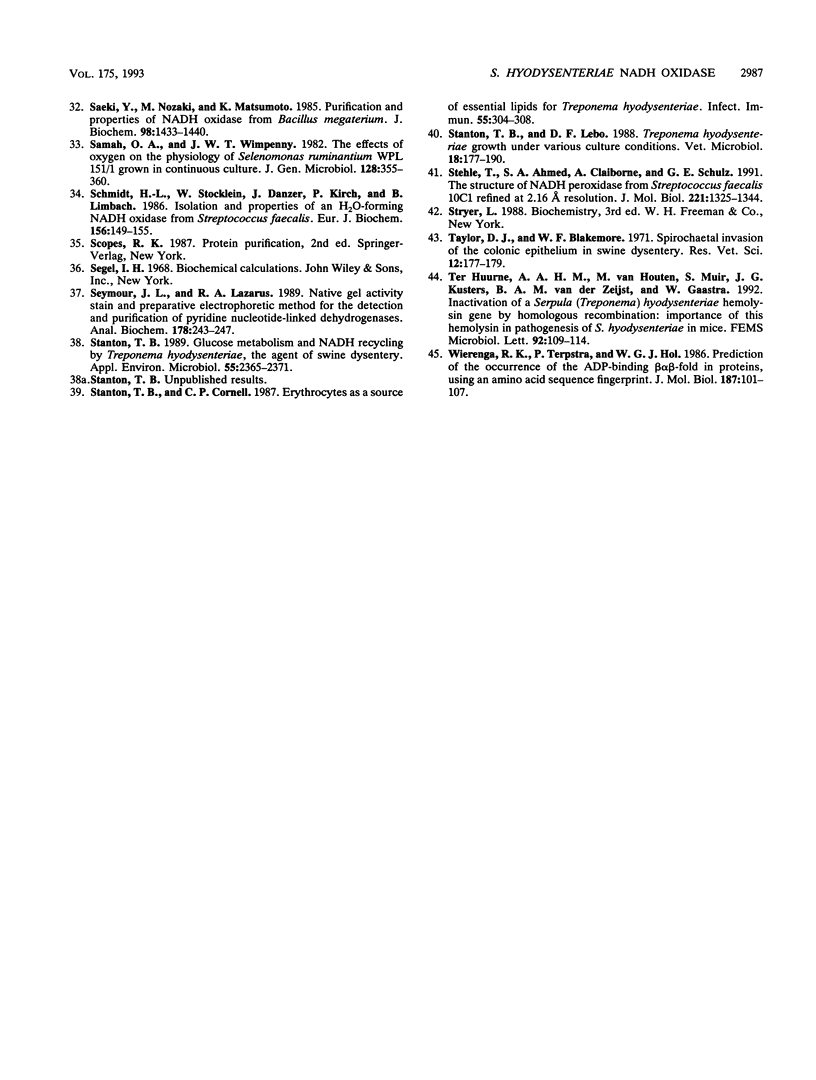

NADH oxidase (EC 1.6.99.3) was purified from cell lysates of Serpulina (Treponema) hyodysenteriae B204 by differential ultracentrifugation, ammonium sulfate precipitation, and chromatography on anion-exchange, dye-ligand-affinity, and size-exclusion columns. Purified NADH oxidase had a specific activity 119-fold higher than that of cell lysates and migrated as a single band during denaturing gel electrophoresis (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [SDS-PAGE]). The enzyme was a monomeric protein with an estimated molecular mass of 47 to 48 kDa, as determined by SDS-PAGE and size-exclusion chromatography. Optimum enzyme activity occurred in buffers with a pH between 5.5 and 7.0. In the presence of oxygen, beta-NADH but not alpha-NADH, alpha-NADPH, or beta-NADPH was rapidly oxidized by the enzyme (Km = 10 microM beta-NADH; Vmax = 110 mumol beta-NADH min-1 mg of protein-1). Oxygen was the only identified electron acceptor for the enzyme. On isoelectric focusing gels, the enzyme separated into three subforms, with isoelectric pH values of 5.25, 5.35, and 5.45. Purified NADH oxidase had a typical flavoprotein absorption spectrum, with peak absorbances at wavelengths of 274, 376, and 448 nm. Flavin adenine dinucleotide was identified as a cofactor and was noncovalently associated with the enzyme at a molar ratio of 1:1. Assays of the enzyme after various chemical treatments indicated that a flavin cofactor and a sulfhydryl group(s), but not a metal cofactor, were essential for activity. Hydrogen peroxide and superoxide were not yielded in significant amounts by the S. hyodysenteriae NADH oxidase, indirect evidence that the enzyme produces water from reduction of oxygen with NADH. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the NADH oxidase was determined to be MKVIVIGCHGAGTWAAK. In its biochemical properties, the NADH oxidase of S. hyodysenteriae resembles the NADH oxidase of another intestinal bacterium, Enterococcus faecalis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahmed S. A., Claiborne A. The streptococcal flavoprotein NADH oxidase. I. Evidence linking NADH oxidase and NADH peroxidase cysteinyl redox centers. J Biol Chem. 1989 Nov 25;264(33):19856–19863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. A., Claiborne A. The streptococcal flavoprotein NADH oxidase. II. Interactions of pyridine nucleotides with reduced and oxidized enzyme forms. J Biol Chem. 1989 Nov 25;264(33):19863–19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco D., Rinaldi A., Savini I., Cooper J. M., Bannister J. V. NADH oxidase from the extreme thermophile Thermus aquaticus YT-1. Purification and characterisation. Eur J Biochem. 1988 Jun 1;174(2):267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glock R. D., Harris D. L., Kluge J. P. Localization of spirochetes with the structural characteristics of Treponema hyodysenteriae in the lesions of swine dysentery. Infect Immun. 1974 Jan;9(1):167–178. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.1.167-178.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer J. M., Wannemuehler M. J. Pathogenesis of Treponema hyodysenteriae: induction of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor by a treponemal butanol/water extract (endotoxin). Microb Pathog. 1989 Oct;7(4):279–288. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOSKINS D. D., WHITELEY H. R., MACKLER B. The reduced diphosphopyridine nucleotide oxidase of Streptococcus faecalis: purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1962 Aug;237:2647–2651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M. The effect of oxygen on the growth and mannitol fermentation of Streptococcus mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1984 Jul;130(7):1819–1826. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-7-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J., Massey V. Purification and properties of milk xanthine dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1992 Oct 25;267(30):21479–21485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M. J., Rosnick D. K., Ulrich R. G., Yancey R. J., Jr Association of Treponema hyodysenteriae with porcine intestinal mucosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1988 Jun;134(6):1565–1576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-6-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klömkes M., Altdorf R., Ohlenbusch H. D. Purification and properties of an FAD-containing NADH oxidase from Mycoplasma capricolum. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1985 Oct;366(10):963–969. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1985.366.2.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike K., Kobayashi T., Ito S., Saitoh M. Purification and characterization of NADH oxidase from a strain of Leuconostoc mesenteroides. J Biochem. 1985 May;97(5):1279–1288. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M., Nakagawa M., Kashiwazaki M., Konno S. Pathological observation on experimental swine dysentery. Natl Inst Anim Health Q (Tokyo) 1979 Fall;19(3):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysons R. J., Kent K. A., Bland A. P., Sellwood R., Robinson W. F., Frost A. J. A cytotoxic haemolysin from Treponema hyodysenteriae--a probable virulence determinant in swine dysentery. J Med Microbiol. 1991 Feb;34(2):97–102. doi: 10.1099/00222615-34-2-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K., Truscott K., Liu X. L., Scopes R. K. A thermostable NADH oxidase from anaerobic extreme thermophiles. Biochem J. 1992 Jun 1;284(Pt 2):551–555. doi: 10.1042/bj2840551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jul 25;262(21):10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuessen M. E., Joens L. A., Glock R. D. Involvement of lipopolysaccharide in the pathogenicity of Treponema hyodysenteriae. J Immunol. 1983 Aug;131(2):997–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien R. W., Morris J. G. Oxygen and the growth and metabolism of Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Gen Microbiol. 1971 Nov;68(3):307–318. doi: 10.1099/00221287-68-3-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. J., Kreutzer R., Reiser C. O., Sprinzl M. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding a H2O2-forming NADH oxidase from the extreme thermophilic Thermus thermophilus HB8 and its expression in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1992 May 1;205(3):875–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. J., Reiser C. O., Kondruweit S., Erdmann H., Schmid R. D., Sprinzl M. Purification and characterization of a NADH oxidase from the thermophile Thermus thermophilus HB8. Eur J Biochem. 1992 May 1;205(3):881–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson G. L. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal Biochem. 1977 Dec;83(2):346–356. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole L. B., Claiborne A. Interactions of pyridine nucleotides with redox forms of the flavin-containing NADH peroxidase from Streptococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem. 1986 Nov 5;261(31):14525–14533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole L. B., Claiborne A. The non-flavin redox center of the streptococcal NADH peroxidase. II. Evidence for a stabilized cysteine-sulfenic acid. J Biol Chem. 1989 Jul 25;264(21):12330–12338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinards R., Kubicki J., Ohlenbusch H. D. Purification and characterization of NADH oxidase from membranes of Acholeplasma laidlawii, a copper-containing iron-sulfur flavoprotein. Eur J Biochem. 1981 Nov;120(2):329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. P., Claiborne A. Cloning, sequence and overexpression of NADH peroxidase from Streptococcus faecalis 10C1. Structural relationship with the flavoprotein disulfide reductases. J Mol Biol. 1991 Oct 5;221(3):857–871. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)80180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. P., Claiborne A. Molecular cloning and analysis of the gene encoding the NADH oxidase from Streptococcus faecalis 10C1. Comparison with NADH peroxidase and the flavoprotein disulfide reductases. J Mol Biol. 1992 Oct 5;227(3):658–671. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y., Nozaki M., Matsumoto K. Purification and properties of NADH oxidase from Bacillus megaterium. J Biochem. 1985 Dec;98(6):1433–1440. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H. L., Stöcklein W., Danzer J., Kirch P., Limbach B. Isolation and properties of an H2O-forming NADH oxidase from Streptococcus faecalis. Eur J Biochem. 1986 Apr 1;156(1):149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour J. L., Lazarus R. A. Native gel activity stain and preparative electrophoretic method for the detection and purification of pyridine nucleotide-linked dehydrogenases. Anal Biochem. 1989 May 1;178(2):243–247. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B., Cornell C. P. Erythrocytes as a source of essential lipids for Treponema hyodysenteriae. Infect Immun. 1987 Feb;55(2):304–308. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.2.304-308.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B. Glucose metabolism and NADH recycling by Treponema hyodysenteriae, the agent of swine dysentery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989 Sep;55(9):2365–2371. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.9.2365-2371.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B., Lebo D. F. Treponema hyodysenteriae growth under various culture conditions. Vet Microbiol. 1988 Oct;18(2):177–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehle T., Ahmed S. A., Claiborne A., Schulz G. E. Structure of NADH peroxidase from Streptococcus faecalis 10C1 refined at 2.16 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991 Oct 20;221(4):1325–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. J., Blakemore W. F. Spirochaetal invasion of the colonic epithelium in swine dysentery. Res Vet Sci. 1971 Mar;12(2):177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga R. K., Terpstra P., Hol W. G. Prediction of the occurrence of the ADP-binding beta alpha beta-fold in proteins, using an amino acid sequence fingerprint. J Mol Biol. 1986 Jan 5;187(1):101–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Huurne A. A., van Houten M., Muir S., Kusters J. G., van der Zeijst B. A., Gaastra W. Inactivation of a Serpula (Treponema) hyodysenteriae hemolysin gene by homologous recombination: importance of this hemolysin in pathogenesis in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992 Apr 1;71(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]