Abstract

To obtain detailed information about gene expression during stamen development in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), we compared, by microarray analysis, the gene expression profile of wild-type inflorescences to those of the floral mutants apetala3, sporocyteless/nozzle, and male sterile1 (ms1), in which different aspects of stamen formation are disrupted. These experiments led to the identification of groups of genes with predicted expression at early, intermediate, and late stages of stamen development. Validation experiments using in situ hybridization confirmed the predicted expression patterns. Additional experiments aimed at characterizing gene expression specifically during microspore formation. To this end, we compared the gene expression profiles of wild-type flowers of distinct developmental stages to those of the ms1 mutant. Computational analysis of the datasets derived from this experiment led to the identification of genes that are likely involved in the control of key developmental processes during microsporogenesis. We also identified a large number of genes whose expression is prolonged in ms1 mutant flowers compared to the wild type. This result suggests that MS1, which encodes a putative transcriptional regulator, is involved in the stage-specific repression of these genes. Lastly, we applied reverse genetics to characterize several of the genes identified in the microarray experiments and uncovered novel regulators of microsporogenesis, including the transcription factor MYB99 and a putative phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase.

Despite rapid advances in understanding the principles of plant development, much remains to be learned about the molecular mechanisms underlying organ and cell-type specification, as well as about the genes that execute these fundamental biological processes. Stamen development represents an excellent system for studying organogenesis and cellular differentiation in plants, because stamens are relatively complex organs, which are composed of many different but well-defined cell types.

After a stamen primordium has been specified by the activity of floral organ identity genes during early flower development (Jack, 2004), cell-type specification and differentiation events take place that lead to the formation of a basal filament and an anther, which contains the male sporogenous tissues. This developmental process culminates in the production of microspores and ultimately, in the release of mature pollen grains.

The development of anthers can be divided into two distinct phases termed microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis. During microsporogenesis (phase 1), which occurs from stage 1 to stage 7 of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) anther development (stages according to Sanders et al., 1999), histospecification, morphogenesis, and meiosis take place. The onset of microgametogenesis (stages 8–14, phase 2) is characterized by the release of microspores from tetrads. Subsequently, these microspores mature into pollen grains. During this process, the tapetum, which surrounds the microspores in the locules of anthers, becomes a secretory tissue and provides nutrients and structural components such as coat proteins for the developing pollen grains. At the same time, the stamen filament elongates and the anther enlarges and expands. Finally, the anther enters a dehiscence program that leads to pollen release when the mature flower opens (Scott et al., 1991, 2004; Goldberg et al., 1993).

Genetic analyses have led to the isolation of several mutants with distinct defects in stamen development (Dawson et al., 1993; Sanders et al., 1999; Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Reddy et al., 2003; Sorensen et al., 2003; Steiner-Lange et al., 2003; Albrecht et al., 2005). Cloning of the genes affected in these mutants resulted in the identification of key regulators of stamen formation. Despite this progress, we have yet to gather sufficient information to fully reconstruct the regulatory pathways underlying angiosperm stamen development.

In recent years, it has been shown that global gene expression profiling by microarray analysis can be a valuable approach for the identification of genes that play important roles in development. However, in plants, most of the microarray-based analyses that have been conducted so far have been done using whole organs (e.g. leaves, roots, or flowers; Zik and Irish, 2003; Wellmer et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2005; Tung et al., 2005), and only a few have focused on determining gene expression in specific cell types (Honys and Twell, 2004; Birnbaum et al., 2005). Consequently, detailed information on cell-type-specific gene expression is currently limited. In addition, few studies have been conducted to date that provided temporal or stage-specific information about gene expression during plant development (Casson et al., 2005; Kubo et al., 2005; Nawy et al., 2005; Wellmer et al., 2006).

Several recent studies have aimed at characterizing gene expression during stamen development on a global scale by microarray analysis (Amagai et al., 2003; Cnudde et al., 2003; Honys and Twell, 2003; Zik and Irish, 2003; Wellmer et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2005; Pina et al., 2005). All of these studies led to the identification of genes with expression in stamens and, in some cases, analyzed specific successive developmental stages (such as during gametophyte development; Honys and Twell, 2004). However, we are still far from obtaining a comprehensive view of temporal and spatial gene expression during stamen formation.

To obtain more detailed information on gene expression in stamens, we compared the gene expression profiles of flowers of mutants that have distinct defects in stamen development (Fig. 1A) to those of wild-type plants by whole-genome microarray analysis. The first of these mutants, apetala3 (ap3), completely lacks petals and stamens but has extra whorls of sepals and carpels (Jack et al., 1992). In a previous study (Wellmer et al., 2004), we analyzed gene expression in the different types of floral organs by comparing the gene expression profiles of whole inflorescences of floral homeotic mutants, including ap3, to those of wild-type plants. These experiments led to the identification of a large number of genes with predominant expression in stamens. However, the results of in situ hybridization experiments suggested that the majority of the identified genes are expressed at late stages of stamen development (Wellmer et al., 2004). Thus, to obtain information about gene expression during early stages of stamen development, we specifically analyzed young floral buds of ap3 mutant plants.

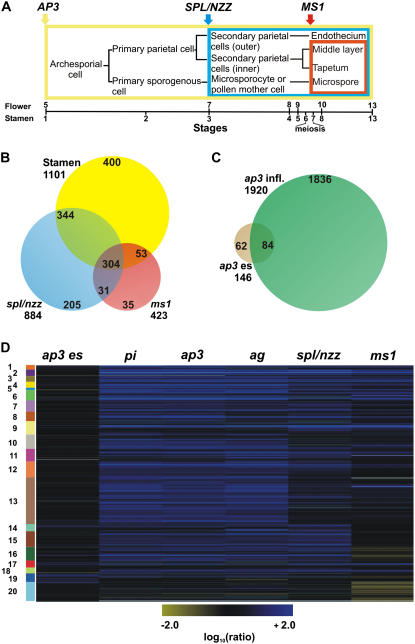

Figure 1.

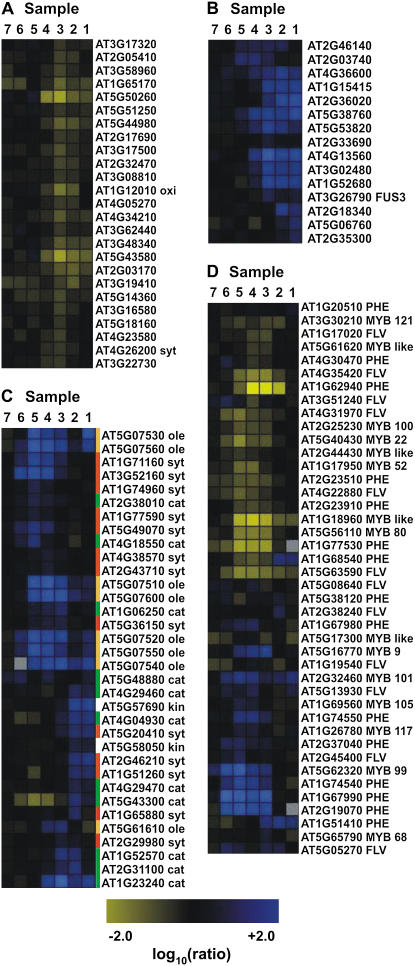

Experimental design and microarray results. A, Diagram depicting cell lineages during wild-type anther development. The colored boxes enclose the tissues or cell types affected in the different mutants included in the analysis. The bar below the diagram shows stages of flower and anther development described by Smyth et al. (1990) and Sanders et al. (1999), respectively. B, A Venn diagram indicates the overlap between genes identified as down-regulated in the ms1 and spl/nzz experiments and genes with predicted expression in stamens (Wellmer et al., 2004; see “Materials and Methods” for details). C, A Venn diagram depicts the overlap between genes identified as differentially expressed in whole inflorescences of ap3 mutant flowers (ap3 infl.; Wellmer et al., 2004) and genes that showed significant expression changes in young floral buds of ap3 mutants (ap3 es) relative to the wild type. D, Self-organizing map for 1,545 genes that either showed differential expression in the ap3 es, spl/nzz, or ms1 experiments or were predicted as specifically or predominantly expressed in stamens (see above). Microarray data from the analyses of gene expression in ag, pi, and ap3 inflorescences (Wellmer et al., 2004) were also included in the cluster analysis. Genes that are down-regulated in a mutant compared to the wild type are depicted in blue and up-regulated genes in yellow. Expression ratios and FC values refer to wild-type/mutant comparisons (Supplemental Table S1); thus, a positive ratio and FC value corresponds to down-regulation in the mutant and, conversely, a negative ratio to up-regulation. The intensities of the colors increase with increasing expression differences as indicated at the bottom. The diagram was generated with the program Rosetta Resolver using log10-transformed expression ratios. Numbered and colored bars on the left indicate distinct clusters of genes (see Supplemental Table S2 for details).

Compared to ap3, the other two mutants included in our analysis, sporocyteless/nozzle (spl/nzz) and male sterile1 (ms1), have more specific defects during stamen formation. In spl/nzz mutants, the nucellus and the pollen sac fail to form, indicating that SPL/NZZ, which encodes a putative transcription factor, plays a key role in the development of both male and female sporangia (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). ms1 mutants do not produce viable pollen but are otherwise phenotypically normal (Wilson et al., 2001; Ito and Shinozaki, 2002). In ms1 mutant plants, degeneration of pollen starts to occur after microspore release from the tetrads, at which time the surrounding tapetal cells appear abnormally vacuolated. Recent results have shown that in contrast to wild-type plants, ms1 mutants lack programmed cell death (PCD) in the tapetum after microspore mitosis I (Vizcay-Barrena and Wilson, 2006), suggesting that MS1, which codes for a nuclear-localized plant homeodomain-containing protein, might control tapetum degeneration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome-Wide Analysis of Gene Expression during Stamen Development

To identify genes expressed during distinct stages of stamen development at a genome-wide scale, we compared, by microarray analysis, the gene expression profiles of flowers of ap3, spl/nzz, and ms1 mutants to those of wild-type flowers. For the identification of transcripts expressed at early stages of stamen development, we dissected older flowers from inflorescences of ap3 mutant plants and the wild type and then collected the inflorescence meristem and floral buds up to early stage 10 for analysis. We refer to these tissue samples hereafter as ap3 early stages, or ap3 es. The second mutant included in our analysis, spl/nzz, shows defects at the earliest steps of sporogenesis. Thus, we expected that genes expressed in sporogenous tissues would be down-regulated in mutant flowers compared to the wild type. Lastly, we analyzed the ms1 mutant to identify genes expressed during pollen development and maturation. To this end, we used the ms1-1 allele, which carries a mutation in a splice acceptor site (Wilson et al., 2001). For both ms1 and spl/nzz, as well as for the wild type, tissue samples containing the inflorescence meristem and floral buds up to stage 13 were collected for analysis. Gene expression profiling experiments were done using oligonucleotide microarrays as described previously (Wellmer et al., 2006). In all cases, at least three independent biological samples were used in separate hybridizations, and the dyes used for labeling of the cohybridized samples were switched in the replicate experiments. After normalization and processing of the microarray data (see “Materials and Methods”), genes were considered as differentially expressed if they showed an absolute fold-change (FC) value of 2 or more between the wild type and a mutant and had been assigned an adjusted P value < 0.05 (throughout this article, a positive ratio or FC value indicates down-regulation of a gene in the mutant relative to the wild type, whereas a negative ratio or FC value indicates up-regulation).

A large number of genes with significant expression changes in a mutant compared to the wild type were identified in all experiments (Supplemental Table S1). To validate the microarray data, we analyzed the expression of several of these genes (see Supplemental Table S6) by quantitative real-time PCR (see “Material and Methods”) and found that the results were in good agreement with those from the microarray experiments (data not shown). We next compared the genes that were identified as differentially expressed in the spl/nzz and ms1 experiments to a previously generated list of genes with predicted specific or predominant expression in stamens (Wellmer et al., 2004). We found that most of the genes (84% and 73%, respectively) that were down-regulated in ms1 or spl/nzz compared to the wild type were also present in that list (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Table S2), confirming that our microarray experiments led to the identification of stamen-expressed genes. These genes are likely expressed in the tissues affected in the individual mutants, i.e. sporogenous tissues and their derivatives in spl/nzz, and the tapetum and microspores/pollen grains in ms1. On the other hand, stamen-expressed transcripts that were not differentially expressed in the ms1 and/or spl/nzz datasets are likely expressed in parts of the stamens that are not affected in these mutants (i.e. connective, vasculature, or filaments).

We also analyzed the dataset derived from the analysis of ap3 mutant flowers. Because these flowers lack both petals and stamens, we expected to find genes that are expressed in both types of floral organs as down-regulated in the experiment. However, the results of our previous analyses indicated that compared to stamens, only a few genes are specifically expressed in petals (Wellmer et al., 2004). Thus, the vast majority of the transcripts identified as down-regulated in ap3 mutant flowers compared to the wild type are likely found in stamens. Overall, the number of differentially expressed genes was strongly reduced in the ap3 es experiment compared to our previous experiment in which we analyzed gene expression in whole ap3 inflorescences (see above). In addition, the overlap between the genes in the individual datasets was relatively small (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Table S2), suggesting that the complement of stamen-expressed transcripts is considerably different at distinct stages of flower development. This idea is in agreement with the recent finding that the transcriptome of young floral buds shows only a limited overlap with that of more mature flowers (Gomez-Mena et al., 2005; Wellmer et al., 2006), as well as with the observation of substantial transcriptional changes during the progression from proliferating microspores to differentiated pollen (Honys and Twell, 2004).

To gain a better overview of the datasets obtained in our experiments, we combined them with those from our previous analysis of floral homeotic mutants (Wellmer et al., 2004) and subjected them to cluster analysis (Fig. 1D; Supplemental Table S2). This analysis resulted in the identification of groups of genes with predicted early (Fig. 1D; cluster 19), intermediate (Fig. 1D; clusters 14 and 15 and, to a lesser extent, clusters 7 and 8), as well as late (Fig. 1D; clusters 1–6) expression during stamen development. To validate these predictions, we searched in the clusters for previously characterized genes with known expression patterns. Among genes with predicted expression at intermediate stages of stamen development, we found MYB26/MALE STERILE35. In agreement with the microarray data, this gene is expressed during early anther development, where it is involved in the formation of the endothecium (Yang et al., 2007). Another example for a gene with expression at intermediate stages is ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA ANTHER20 (ATA20), whose mRNA is localized in tapetal cells during postmeiotic microspore and pollen development (Rubinelli et al., 1998). Among genes with predicted expression at late stages of stamen development, we found several that are known to be involved in pollen development, such as ATA7 and ATA27 (Rubinelli et al., 1998), BRASSICA CAMPESTRIS POLLEN PROTEIN1 (Xu et al., 1995), GLYCINE-RICH PROTEIN17 (GRP17), and GRP18 (Ferreira et al., 1997). Taken together, the results of this analysis support the idea that the experimental design we have used allowed the identification of genes expressed at different stages of stamen development.

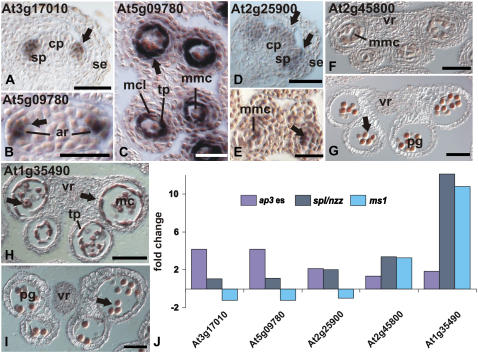

To further verify the results of the microarray analyses, we performed in situ hybridization experiments for selected genes (Fig. 2). To this end, we focused on transcription factor-coding genes because of their important role in the control of development. We found that the temporal and spatial expression patterns of these genes are, in general, in good agreement with the data derived from the microarray experiments (Fig. 2J). For instance, the genes At3g17010 (a likely target of the floral homeotic factor AGAMOUS; Gomez-Mena et al., 2005) and At5g09780, which encode putative B3-type transcription factors, were identified in the ap3 es but not in the in spl/nzz or ms1 experiments (Fig. 1D, cluster 19), suggesting expression at early stages of stamen development before the formation of sporogenous tissues. In agreement with this idea, our in situ hybridization experiments revealed expression of these genes in emerging stamen primordia (Fig. 2, A and B). However, both genes are also expressed in the tapetum and the middle layer of developing anthers until stage 6 of anther development (Fig. 2C; data not shown) and thus in tissues that are affected in spl/nzz mutants. It is possible that the identification of these genes was precluded in the spl/nzz experiments due to the fact that we used whole inflorescences for microarray analysis, whereas for the ap3 es experiments, floral buds of early and intermediate stages were collected (see above). Thus, the transcripts of these genes might have been too dilute in the samples used for the spl/nzz experiments to be reliably detected.

Figure 2.

Microarray data and expression patterns of selected genes. A to I, Expression patterns were analyzed in wild-type flowers by in situ hybridization. A, B, and D, Longitudinal sections are shown. For all others, transverse sections were used. Arrows indicate regions of expression. A, Expression of At3g17010, encoding a B3 domain-containing protein, in emerging stamen primordia at floral stage 6. B and C, Expression of At5g09780, which encodes another B3 domain-containing protein. At floral stage 7, expression was first observed in subepidermal cells of stamen primordia from which archesporial cells are derived (B). At floral stage 8, expression was detected in tapetal cells and in the middle cell layer (C). At this stage, the expression of At3g17010 overlaps with that of At5g09780 (not shown). D, Expression of At2g25900, encoding a zinc finger-containing protein, in stamen and carpel primordia was first observed in stage 6 floral buds. E, At floral stage 8, expression was found in microspore mother cells, the tapetum, and the middle cell layer. F and G, Expression of At2g45800, which codes for a NtLIM1-like protein, in the tapetum and in microspores of floral buds at stages 9 and 10, respectively. H and I, Expression of At1g35490, which encodes a bZIP transcription factor, is strong in the tapetum and in microspores at late floral stage 9 (H) and is restricted to microspores after tapetum degeneration at late stage 10 (I). J, FC values derived from the individual microarray experiments (as indicated) are shown for the genes described above. A positive FC value corresponds to down-regulation in the mutant and, conversely, a negative FC value to up-regulation. ar, Archesporial cell; cp, carpel primordium; mmc, microspore mother cell; mcl, middle cell layer; pg, pollen grain; se, sepal; sp, stamen primordium; ta, tapetum; vr, vascular region. Scale bars = 50 μm (A, D, G–I) and 25 μm (B, C, E, and F).

The unique spatial expression patterns of At3g17010 and At5g09780 and the nature of the corresponding proteins suggest that they might be involved in key aspects of stamen development. Recent results identified additional B3-type transcription factors that are expressed during early flower development (Gomez-Mena et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Wellmer et al., 2006). The spatial expression patterns of some of these genes partially overlap with those of At3g17010 and At5g09780, suggesting that they might act in a redundant manner in the control of stamen development. In agreement with this idea, the inactivation of At3g17010 resulted in no discernable mutant phenotypes (see below).

We also determined the expression pattern of gene At2g25900, which encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor. This gene was identified in both the ap3 es and spl/nzz datasets, but not in that for ms1, suggesting that its expression is restricted to the early and/or intermediate stages of stamen formation. Indeed, expression of this gene was found in young stamen and carpel primordia (Fig. 2D). Later in development, its expression was confined to anthers (Fig. 2E). No expression of this gene was detectable after stage 6 of anther development (data not shown).

Finally, we characterized the expression patterns of two genes (At2g45800 and At1g35490) encoding a putative NtLIM1-like protein and a bZIP transcription factor, respectively (Fig. 2, F–I), and again found that the expression patterns of these genes are in agreement with the predictions derived from the microarray data (Fig. 2J); both genes are expressed at low levels at early stages of anther development, but strongly in the tapetum (At1g35490) and pollen grains (At1g35490 and At2g45800) at stages 9 to 11 of flower development. In summary, the spatial and temporal expression patterns for all genes tested were in accordance with the predictions based on the microarray data.

Gene Expression during Microspore Development

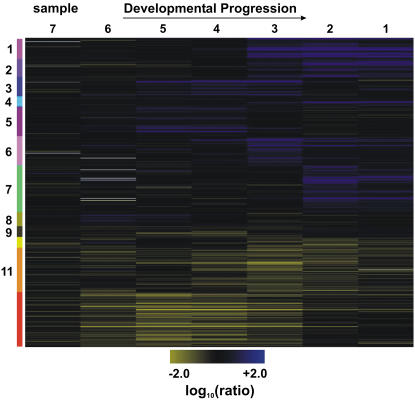

To gain more detailed insights into the transcriptional program underlying microspore development in Arabidopsis, we made further use of the ms1 mutant, which lacks viable pollen. We collected flowers from ms1 and wild-type plants and pooled them according to their developmental stages into seven tissue samples, where sample 1 contained mature (stage 13) flowers and subsequent samples contained successively younger flowers, with sample 7 containing the youngest floral buds and the inflorescence meristem (see “Materials and Methods” for details). Using whole-genome microarray analysis, we identified 1,516 genes with significant expression changes between the wild-type and ms1 mutant flowers across this developmental series (Supplemental Table S1). Because ms1 mutants show developmental defects only at relatively advanced stages of flower development (Ito and Shinozaki, 2002), we expected to find no or only a few gene expression differences in the samples that were comprised of the youngest floral buds (i.e. samples 7 and 6). In fact, the number of differentially expressed genes in these samples was low, while their number was considerably higher in those samples (i.e. 5–1) that contained more mature flowers (Supplemental Table S1).

Cluster analysis of the microarray data for the differentially expressed genes allowed the identification of groups of genes that are predicted to be coexpressed at different developmental stages (Fig. 3). For example, clusters 3 and 5 included genes that were down-regulated in those tissue samples that contained floral buds in which morphological differences in ms1 mutant flowers first become apparent. This suggests that these genes might act immediately downstream of MS1 in the regulation of microsporogenesis. In contrast, clusters 1 and 2, as well as clusters 6 and 7, comprised genes with predicted late expression during stamen development. These genes are likely predominantly expressed in pollen grains, because the tapetum (the other cell type affected in ms1 mutants) starts to degenerate before the second mitotic division of microspores (Sanders et al., 1999) and is absent in flowers at the developmental stage for which we observed the expression changes. To test this idea, we compared the genes in these clusters, as well as those in clusters 3 and 5, to transcripts previously predicted as selectively expressed in pollen grains (Pina et al., 2005). While only a few (five of 239) of these pollen-selective genes were found in clusters 3 and 5, a significant portion (185 of 632) was present among the genes with predicted late expression (Supplemental Fig. S1A; Supplemental Table S3). Thus, it appears that the genes in the clusters are indeed predominantly expressed in pollen grains.

Figure 3.

Progression of gene expression in developing anthers of ms1 mutant flowers. A, Self-organizing map for 1,516 genes with significant expression changes in ms1 mutant flowers compared to the wild type at different stages of development. Tissue samples were collected as outlined in “Materials and Methods.” Genes that are down-regulated in ms1 mutant flowers compared to the wild type are depicted in blue and up-regulated genes in yellow. The intensities of the colors increase with increasing expression differences as indicated on the bottom. The diagram was generated with the program Rosetta Resolver using log10-transformed expression ratios. Numbered and colored bars on the left indicate distinct clusters of genes used for further functional analysis (see text for details).

We next analyzed all the genes that were identified as differentially expressed in the ms1 developmental series (regardless of their cluster classification) with respect to the lists of transcripts with predicted pollen-specific or pollen-enriched expression (Pina et al., 2005). We found that 28% (428 of 1,516) of the genes that we identified as down-regulated in ms1 mutants were also present in the list of pollen-enriched transcripts and that 15% (227 of 1,516) were previously judged as pollen selective (Pina et al., 2005; Supplemental Fig. S1B; Supplemental Table S3). A smaller overlap (20%; 312 of 1,516) was found when our data were compared to genes with predicted expression in bicellular pollen grains and mature pollen (Honys and Twell, 2004; Supplemental Table S3).

While most genes identified as differentially expressed in the ms1 experiments were down-regulated in the mutant compared to the wild type, two of the clusters (11 and 12) contained genes that were up-regulated in ms1 mutant flowers. Among these genes, we found a relatively large portion (83 of 488) that had been previously predicted as stamen expressed (Wellmer et al., 2004). This result was unexpected, as a disruption of normal stamen development and a lack of viable pollen in ms1 mutants should typically result in a down-regulation and not an up-regulation of stamen-expressed genes. Notably, most of the up-regulated genes were detected as differentially expressed in consecutive tissue samples (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S1). This suggested that these genes might be expressed for a longer period of time in anthers of ms1 plants compared to the wild type. Thus, we hypothesized that MS1 is involved in the stage-specific repression of these genes (see below).

Validation of Predicted Expression Patterns

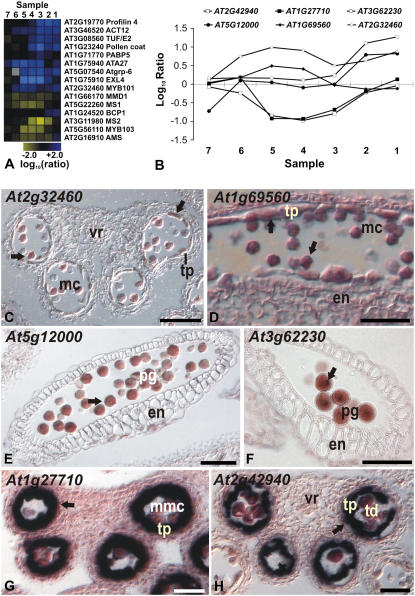

To validate the data of the ms1 microarray experiments, we searched among the 1,516 differentially expressed genes for genes with known expression in male sporogenous tissues. We found the majority of these genes in the dataset, suggesting that the microarray analysis led to the identification of most, but not all, genes involved in pollen formation. We next compared the expression profiles of these genes to their published expression patterns and found them, in general, to be in good agreement (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Table S4). For example, genes with known pollen-specific expression were found in those clusters that contain genes with predicted expression during late stages of microsporogenesis (see above). Among genes with early/intermediate expression, we found several members of the oleosin gene family, which encode major components of the pollen coat (Mayfield et al., 2001). These genes are predominantly expressed in the tapetum during stage 9 and 10 of anther development (Ferreira et al., 1997; Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

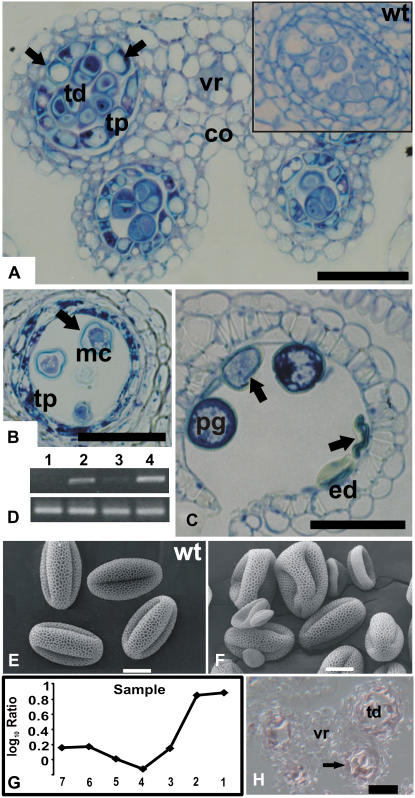

Microarray data and results of in situ hybridizations for selected genes whose expression is affected in ms1 mutant flowers. A, Stage-specific effects of MS1 on the expression of selected genes with previously characterized expression patterns. The diagram was generated as outlined for Figure 3. B, Log10-transformed expression ratios from the analysis of individual tissue samples (as indicated) are shown for the genes described below. C to H, Result of in situ hybridization experiments for selected genes. Arrows indicate regions of expression. C and D, MYB101 (At2g32460) and MYB105 (At1g69560) are expressed in pollen grains and in the tapetum. Transverse (C) and longitudinal (D) sections through anthers of stages 11 and 9, respectively, are shown. E, At5g12000, encoding a protein kinase, is expressed exclusively in mature pollen grains. A longitudinal section through a stage 12 anther is shown. F, Expression of At3g62230, encoding an F-box protein, was observed in germinative cells of mature pollen grains. A longitudinal section through a stage 12 anther is shown. G, The expression of At1g27710, which encodes a Gly-rich protein, is exclusively observed in tapetal cells. H, Expression of At2g42940, which encodes an AT-hook DNA-binding protein, was found in the tapetum after the completion of meiosis. Note that this gene has a very narrow window of expression during tapetum development similar to that of At1g27710. G and H, Transverse sections through anthers of stage 8 and 7, respectively. en, Endothecium; mc, microspore; mmc, microspore mother cell; pg, pollen grain; td, tetrads; tp, tapetum; vr, vascular region. Scale bars = 50 μm (C and E) and 25 μm (D, F, and G).

We next tested whether our results could be used to accurately predict the expression dynamics of genes not previously characterized. To this end, we determined, by in situ hybridization using wild-type flowers, the expression patterns of several of the genes identified as differentially expressed in the ms1 developmental series (Fig. 4, B–H). Among these genes were two that code for the transcription factors MYB101 (At2g32460) and MYB105 (At1g69560). The expression pattern of MYB101 had been previously characterized by in situ hybridizations (Gocal et al., 2001), but in contrast to our predictions, no expression in stamens had been reported. In our in situ hybridization experiments, however, MYB101 transcripts, as well as those of MYB105, were clearly detectable in microspores and in the tapetum at stages 11 and 10, respectively, of anther development (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, the expression patterns of these two genes are in agreement with the results of our microarray data, which suggested expression during early and intermediate stages of stamen formation (Fig. 4B). In addition, expression of MYB101 in pollen has also been detected, using microarrays, in a study of male gametophyte development (Honys and Twell, 2004).

Next, we analyzed two genes that we had predicted to be expressed during late stages of stamen development: At5g12000, which codes for a protein kinase, and At3g62230, encoding an F-box family protein. The results of in situ hybridization experiments showed that both genes are expressed in mature pollen (Figs. 4, E and F). Notably, At3g62230 is initially uniformly expressed in binucleated pollen grains, but after the second mitotic division, its mRNA is predominantly localized in sperm cells (Fig. 4F).

Finally, we tested two genes for which we had predicted a prolonged expression in ms1 mutant flowers compared to the wild type (see above): At1g27710, which encodes a Gly-rich protein, and At2g42940, encoding a protein with an AT-hook domain. We found that both genes are specifically expressed in the tapetum during a narrow time window, soon after the callose walls that surround tetrads degenerate (Fig. 4, G and H). Notably, in dozens of sections examined, we never observed expression of At2g42940 in all six stamens of a flower. Instead, we detected simultaneous expression in anthers of stamens in either medial or lateral position but never in medial and lateral stamens at the same time. Thus, it appears that At2g42940 is a good molecular marker for the slight developmental delay of lateral stamens when compared with medial ones (Smyth et al., 1990). Expression patterns similar to that of At1g27710 have been described for several other regulators of microsporogenesis that are essential for normal pollen formation. These genes included ABORTED MICROSPORES (At2g16910; Sorensen et al., 2003), MALE MEIOCYTE DEATH1 (At1g66170), MYB80 (At5g56110; Li et al., 1999; Stracke et al., 2001), and MS2 (At3g11980; Aarts et al., 1997). As for At2g42940 and At1g27710, we found that most of these genes also showed a prolonged expression in ms1 mutant flowers (Fig. 4A). This result suggested that MS1 functions by repressing the transcription of these genes at a specific stage of microsporogenesis (see above). To test this idea, we performed in situ hybridizations for one of the genes (At2g42940) in the ms1 background. As predicted, expression of this gene was detected at later stages of anther development in ms1 mutants compared to the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S2).

During microspore mother cell meiosis, tapetal cells undergo a process of redifferentiation that triggers a dramatic change in their structure and metabolism; they lose their cell wall and become highly secretory. The specific expression of several key regulatory genes at this stage of microsporogenesis suggests that they might be involved in the control of the tapetal redifferentiation process. Notably, expression of MS1, which normally occurs in the tapetal cell layer of anthers during a relatively short period of time at stage 10 of flower development (Ito and Shinozaki, 2002), is also prolonged in the ms1 mutant (Fig. 4A). Thus, it appears that MS1 functions in part by repressing its own expression. Taken together, these results suggest that loss of MS1 function leads to a disruption of the normal progression of tapetum development, thus extending the expression of a class of genes that are normally active for a very brief period of time. This hypothesis is corroborated by the temporal At2g42940 expression pattern in ms1 flowers where hybridization signal was detected in medial and lateral anther (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Functional Analysis of Genes Acting during Microsporogenesis

We next analyzed using the software GOToolBox (Martin et al., 2004) whether Gene Ontology (GO) terms were statistically over- or underrepresented either among the genes identified as differentially expressed in the individual ms1 tissue samples or in the different gene clusters derived from this dataset (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table S1). In agreement with the known importance of lipid synthesis and storage in tapetum and pollen grain development and function (Ferreira et al., 1997; Piffanelli et al., 1998), one of the GO terms that showed a significant overrepresentation during specific stages of microsporogenesis comprises genes involved in lipid metabolism (Supplemental Fig. S3). In particular, we found an overrepresentation of this class of genes in those samples (5–3) that correspond to stages 9 and 10 of stamen development (Supplemental Fig. S3A).

Analysis of these genes using the MAPMAN pathway analysis tool (Usadel et al., 2005) showed that genes involved in lipid synthesis (Fig. 5C, red bars) are mainly expressed during the early stages of microsporogenesis (detected in samples 6–4), while transcript levels of oleosin-like genes (Fig. 5C, orange bars), which mediate lipid storage, are high at intermediate and late stages (samples 5–1). Most of the genes involved in lipid catabolism are predominantly expressed during late stages (samples 3–1) of microsporogenesis (Fig. 5C, green bars).

Figure 5.

Expression of selected functionally related genes throughout anther development as derived from the ms1 experiments. Grouping of the genes was done with Rosetta Resolver using an agglomerative hierarchical clustering algorithm and Pearson correlation as a proximity measure. Genes that are down-regulated in the mutant compared to the wild type are depicted in blue and up-regulated genes in yellow. The intensities of the colors increase with increasing expression differences, as indicated at the bottom. A, Genes involved in protein degradation or ethylene biosynthesis. B, LEA genes and genes involved in GA response. C, Genes involved in lipid metabolism or storage. Three distinct sets of genes involved in different aspects of lipid metabolism are shown. Genes involved in lipid synthesis (red bars) are predominantly repressed in samples 6, 5, and 4; oleosin-like genes (orange bars), which are required for lipid storage, are repressed in samples 5, 4, and 3; and most of the genes that mediate lipid catabolism (green bar) are down-regulated in samples 3, 2, and 1. D, Genes encoding MYB transcription factors and genes involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism. cat, Catabolism; des, desaturase; FLV, genes involved in flavonoid synthesis; kin, kinase; ole, oleosin; PHE, genes involved in the synthesis of phenolic compounds; syt, synthesis. Annotation of MYB or MYB-like genes is based on Larkin et al. (2003).

We also found in the dataset a significant enrichment of genes assigned to GO terms Metabolism and External Encapsulating Structure, which likely play important roles during pollen development (Supplemental Fig. S3, E and F). Genes assigned to the term Metabolism were enriched in clusters 3 and 5, which may be a result of the preponderance in these clusters of genes that are expressed in the metabolically highly active tapetal cells. In contrast, this term was underrepresented in clusters 2, 6, and 7, which are enriched in genes expressed in pollen grains at late stages of development (see above; Supplemental Fig. S3E). Genes assigned to GO term External Encapsulating Structure were enriched in clusters 1, 2, and 7 (Supplemental Fig. S3F). These genes are likely involved in pollen wall formation.

We also investigated, using the MAPMAN tool, the expression of genes during microsporogenesis that code for components of the protein degradation system. Protein degradation is a hallmark of PCD, which occurs in the tapetum from stages 11 to 12 of anther development. In wild-type plants, the tapetum is completely degenerated, and mature pollen grains are visible within locules at the tricellular pollen stage (Sanders et al., 1999). In contrast, in ms1 mutant plants, the tapetum is still evident at this stage (Ariizumi et al., 2005), although the tapetal cells are morphologically abnormal (Vizcay-Barrena and Wilson, 2006). It has been recently suggested that these defects might be due to an absence of PCD in the tapetum of ms1 mutant plants (Vizcay-Barrena and Wilson, 2006). Instead, PCD appears to take place in microspores at late stages of flower development, possibly as a consequence of abnormal tapetum development (Vizcay-Barrena and Wilson, 2006). Our microarray analysis showed that genes involved in protein degradation are generally up-regulated in ms1 mutants compared to the wild type, predominantly in mature or late-stage flower buds (Fig. 5A). This result suggests that MS1 malfunction leads to a significant delay in the onset of PCD in mutant anthers. While it is currently unclear in which cell type(s) these genes are expressed, our results are in agreement with an occurrence of PCD in microspores during late stages of ms1 stamen development and a deviation of the regular program of PCD acting in the tapetum.

We next investigated the possible role of genes involved in the metabolism of, or the response to, phytohormones in microsporogenesis. Recently, Mandaokar et al. (2006) have used microarray analysis to follow gene expression in stamens of the jasmonate (JA)-biosynthesis mutant opr3, which is male sterile, after exogenous JA treatment. Their results suggested that the expression of a relatively large portion of genes involved in stamen development is JA dependent. In agreement with this idea, a comparison of the list of JA-responsive genes derived from these experiments with the differentially expressed genes from the ms1 developmental series revealed a significant overlap (Supplemental Table S3).

We also found differentially expressed genes in the ms1 dataset encoding enzymes involved in ethylene synthesis (Fig. 5A) as well as genes with known functions in abscisic acid (ABA) signaling and/or response. The latter group included the transcription factor-coding gene FUSCA3 (FUS3) and several members of the LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT (LEA) gene family, as well as known ABA-response genes (Fig. 5B). FUS3 is known to be involved in the ABA-dependent regulation of seed storage protein-coding genes and LEA genes, which are considered to represent terminal outputs of the seed maturation program (Kroj et al., 2003). In ms1 plants, repression of FUS3 coincided with repression of 11 genes of the LEA family and an up-regulation of four known ABA-response genes (Fig. 5B). Thus, ABA-dependent gene regulation via FUS3 might not be limited to seed development.

We next identified all transcription factor-coding genes in the ms1 dataset to assess the complexity of the gene regulatory networks underlying microsporogenesis. We found a total of 92 transcription factors and putative DNA-binding proteins from distinct gene families (Supplemental Fig. S4; Supplemental Table S2). Most of these genes were differentially expressed in the tissue samples containing floral buds of early and intermediate stages, while a significant underrepresentation was observed at late stages of microsporogenesis (Supplemental Fig. S3B). This result suggests that the degree of transcriptional control is reduced during pollen maturation. In fact, it has been previously described that pollen grains undergo a period of relatively low transcriptional activity at late stages of development (Mascarenhas, 1990; Honys and Twell, 2004).

An important step in microspore formation is the synthesis of the pollen wall and the pollen coat. The pollen wall is based on the polymer sporopollenin, which is largely composed of acyl lipids and phenylpropanoid precursors, while the pollen coat contains a complex mixture of proteins, lipids, and phenolic compounds such as flavonoids (Piffanelli et al., 1998; Hsieh and Huang, 2007). The regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism, which contributes to the formation of both structures, is relatively well understood and appears to be dependent to a large extent on the activity of R2R3 MYB transcription factors (Borevitz et al., 2000; Nesi et al., 2001; Preston et al., 2004). To identify genes that might be involved in the regulation of spororopollenin and pollen coat formation, we compared, using cluster analysis, the expression profiles of R2R3 MYB transcription factor and MYB-like coding genes identified in the ms1 developmental series to those of genes known or presumed to be involved in phenylpropanoid metabolism. We found that the temporal expression patterns of these genes were in many cases closely correlated (Fig. 5D), suggesting that some of the MYB transcription factors identified in our experiment might be involved in the regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism. For three of the genes, namely MYB99 (At5g62320), MYB101 (At2g32460), and MYB105 (At1g69560), we confirmed by in situ hybridization experiments that they are indeed expressed during pollen development (see below).

Identification of Novel Regulators of Microsporogenesis

The microarray experiments described above led to the identification of a large number of genes expressed during distinct stages of stamen development. We analyzed several of these genes by reverse genetics to understand their function in stamen formation. To this end, we focused on genes encoding proteins with putative roles in transcriptional regulation or signal transduction because of their well-known functions in the control of development. In total, we analyzed T-DNA insertion lines for 14 genes (Supplemental Table S5), as well as RNA interference (RNAi) lines for two additional genes (At2g42940 and At1g12080). Two of the T-DNA insertion lines (for genes At2g40850 and At5g62320) and one of the RNAi lines (for gene At2g42940) showed specific defects in microspore formation, while all others had no discernable mutant phenotypes. The lack of a mutant phenotype for most of the genes we analyzed by reverse genetics is likely a consequence of the high degree of functional redundancy found in Arabidopsis, especially among duplicated genes (Nawy et al., 2005; Overvoorde et al., 2005). In fact, for most of the genes tested, we found paralogs in the Arabidopsis genome (data not shown).

Anthers of plants homozygous for a T-DNA insertion in At2g40850 contained only a small number of pollen grains, and consequently, few seeds were produced per plant. Microscopic examination of the mutant anthers revealed that meiosis, the earliest step of pollen formation, was not affected. However, after tetrads had formed, the cells of the tapetum showed abnormally enlarged vacuoles (Fig. 6A). Later in development, pollen grains exhibited irregular shapes and, in mature anthers, most of them had collapsed (Fig. 6, B and C, E and F).

Figure 6.

Characterization of a T-DNA insertion line for gene At2g40850. A to C, Transverse sections through mutant anthers. The sections were stained with toluidine blue and then photographed using bright-field microscopy. A, Section through a stage 6 mutant anther. Inset shows a section through a locule from a wild-type plant at the same developmental stage. Note the abnormally enlarged vacuoles of tapetal cells in the mutant (arrows). Representative images are shown of multiple sections of mutant and wild-type anthers that were analyzed. B and C, Sections through mutant anthers at stage 11 (B) and at stage 12 (C) after breakage of the septum. Note the collapsed pollen grains (marked by arrows). D, Effect of the T-DNA insertion on At2g40850 expression. Top, Gene-specific primers for At2g40850 were used for RT-PCR; bottom, primers for actin were used as a control to verify that roughly the same amount of cDNA was used in the different reactions. RNA was isolated from the following tissues: whole inflorescences of plants mutant for At2g40850 (lane 1); flower buds of wild-type plants that were smaller (lane 2) or larger (lane 3) than 0.5 mm; whole inflorescences of wild-type plants (lane 4). E and F, Scanning electron micrographs of pollen grains from wild-type plants (E) and from the mutant line for At2g40850 (F). Microarray data for At2g40850. G, Log10-transformed ratios from the analysis of temporal gene expression in ms1 mutant flowers are shown. At2g40850 showed two distinct peaks of expression, one at an early stage of stamen development and a second at later stages, when mature pollen grains are formed. H, Result of in situ hybridization for At2g40850. A transverse section through a stage 7 anther is shown. A weak hybridization signal was obtained in tapetum and tetrads (arrow). co, Connective; ed, endothecium; mc, microspore; pg, pollen grain; tp, tapetum; tetrads, td; vr, vascular region. Scale bars = 30 μm (A, B, C, and H) and 10 μm (E and F).

The results of reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis showed that At2g40850, which codes for a putative phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PtdIns 4-kinase), is predominantly expressed during flower development (Fig. 6D), as well as at lower levels in siliques and stems of wild-type plants (data not shown). In the homozygous insertion line for At2g40850 (in which the T-DNA lies 299 bp downstream of the start codon of the intronless gene), the corresponding gene transcripts were not detectable (Fig. 6D), suggesting that this line represents a null allele. Our microarray data for At2g40850 (Fig. 6G) suggested two peaks of expression: one during early anther development at around the time of tetrad formation and a second at late stages after the formation of pollen grains. In situ hybridization experiments confirmed that At2g40850 is indeed expressed during early anther development in tetrads and the tapetum (Fig. 6H), as well as in pollen grains (data not shown). Thus, At2g40850 is expressed in the tissues affected in the T-DNA insertion line, and the developmental stage at which morphological defects become apparent in the mutant corresponds with the onset of its expression.

PtdIns 4-kinases catalyze the phosphorylation of PtdIns to PtdIns-4-phosphate, a lipid believed to be a precursor for the synthesis of the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol (Mueller-Roeber and Pical, 2002). These molecules play important roles in animal development, but their functions in plants are poorly understood. Two major types (termed II and III) of PtdIns 4-kinases have been identified in animals and plants. At2g40850 encodes a type II PtdIns 4-kinase, which has been previously named PI4Kγ1 (Mueller-Roeber and Pical, 2002). While the function of type II PtdIns 4-kinases in plants is unknown, it has been suggested that in animals, they are involved in the regulation of intracellular trafficking (Wang et al., 2003; Salazar et al., 2005). Thus, the mutant phenotype observed for the At2g40850 insertion line might be caused by a malfunction of this essential cellular process. Indeed, intracellular trafficking appears to be an essential mechanism for proper tapetum and microspore development, as a disruption in MALE GAMETOGENESIS IMPAIRED ANTHERS, which encodes a protein with high abundance in the endoplasmic reticulum, causes male sterility (Jakobsen et al., 2005).

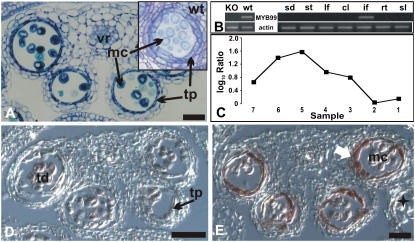

The T-DNA insertion line for At5g62320, which encodes the transcription factor MYB99, formed small siliques with only few viable seeds (data not shown). To test whether this phenotype was a consequence of partial male sterility, we studied pollen morphology in the mutant in detail. Scanning electron microscopy of pollen grains from plants homozygous for the T-DNA insertion revealed no morphological differences compared to wild-type pollen (data not shown). However, light microscopy showed that tapetal cells were relatively thin compared to those from the wild type at the same stage of development (Fig. 7A) and the number of viable pollen grains tested by fluorescein diacetate stain was smaller the T-DNA insertion line (data not shown; Regan and Moffatt, 1990). RT-PCR analysis revealed that MYB99 is expressed solely in inflorescences and that the T-DNA insertion (which is localized in the second exon of MYB99, or 505 bp from the start codon of the cDNA) leads to a complete loss of transcript accumulation (Fig. 7B). The results of the ms1 developmental series, discussed above, suggested onset of MYB99 expression after the tetrad stage (Fig. 7C). In situ hybridization experiments confirmed this prediction and showed that MYB99 expression is confined to stages 8 and 9 of anther development (Fig. 7, D and E). Besides MYB99, several other genes that code for MYB transcription factors have been reported to be involved in the regulation of pollen formation (Preston et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2007). One of these genes, MYB80 (At5g56110, formerly known as AtMYB103), belongs to the same phylogenetic subgroup as MYB99 (Li et al., 1999; Stracke et al., 2001), and the expression patterns of these two genes partially overlap (Higginson et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that the relative weak effects on microsporogenesis observed after a disruption of MYB99 and MYB103 are due to partial functional redundancy.

Figure 7.

Characterization of a T-DNA insertion line for MYB99. A, Transverse section through a myb99 mutant anther. Cells are morphologically similar to their counterparts in wild-type anthers (see inset), with the exception of tapetal cells at the vacuolated microspore stage. A representative image is shown of multiple sections of mutant and wild-type anthers that were analyzed. B, MYB99 expression in distinct organs or tissues (sd, Seedling; st, mature stamen; lf, leaf; cl, cauline leaf; if, inflorescence; rt, roots; sl, siliques) of wild-type plants (right) and in whole inflorescences of the myb99 mutant line (KO) compared to the wild type (wt; left). Top, Gene-specific primers for MYB99 were used for RT-PCR; bottom, primers for actin were used as a control to verify that a similar amount of cDNA was used in the different reactions. MYB99 transcripts were only detected in inflorescences. C, Microarray data for MYB99. Log10-transformed ratios from the analysis of temporal gene expression in ms1 mutant flowers are shown. MYB99 expression peaks at early stages of stamen development. D and E, Results of in situ hybridizations for MYB99. D, Transverse section through a stage 7 anther. Only weak hybridization signals were obtained. E, Transverse section of an anther at stage 9 showing expression of MYB99 exclusively in the tapetum (arrow). A star indicates a lateral anther at a later stage of flower development, in which MYB99 expression was not detectable in the tapetum. mc, Microspores; pg, pollen grain; tp, tapetum; td, tetrads; vr, vascular region. Scale bars = 30 μm.

Evidence for the role of another gene identified in the microarray experiments in the regulation of microsporogenesis came from the analysis of At2g42940, which encodes a protein with an AT-hook motif. The AT-hook motif was first identified in High Mobility Group proteins and is thought to mediate DNA binding (Reeves and Beckerbauer, 2001). As described above, At2g42940 is expressed during a very narrow window of time exclusively in the tapetum and is up-regulated in ms1 mutant plants compared to the wild type (Fig. 4, A and H). As no T-DNA insertion line was available for this gene in the public seed collections, we generated a gene-specific RNAi construct and introduced it into wild-type plants (see “Materials and Methods” for further details). Plants in which At2g42940 had been silenced by RNAi formed smaller siliques and a reduced number of seeds compared to the wild type (Supplemental Fig. S5, C and D). The development of the tapetum in these transgenic lines was comparable to that observed in wild-type plants up to stage 10 of anther development. At stage 11, however, pollen grains of the transgenic plants showed thin cell walls and some of them had collapsed (Supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). The relatively weak phenotype of the RNAi lines could be due to functional redundancy, as another gene (At2g45430) that encodes a protein with an AT-hook domain and whose temporal expression pattern was identical to that of At2g42940, was also identified in the ms1 microarray experiments (Supplemental Table S1).

In summary, the experiments described here resulted in a detailed description of temporal gene expression for flower buds of Arabidopsis undergoing stamen organogenesis and in the identification of genes that might regulate important developmental processes such as the formation of microspores. Furthermore, our results show that MS1, a key regulator of microsporogenesis, restricts the expression of certain genes to a narrow time window during anther development. However, the exact mechanism by which MS1 acts remains unknown. It has been shown for several other plant homeodomain-containing proteins in both animals and plants that they are involved in gene regulation (Greb et al., 2007). Thus, MS1 may directly control the expression of some of the identified genes. Alternatively, a prolonged expression of certain genes in the ms1 mutant relative to the wild type might be an indirect consequence of the delayed tapetal PCD.

The functional characterization of several of the genes that were identified in the microarray experiments yielded novel regulators of microsporogenesis. This result suggests that a systematic study of the identified genes should reveal additional genes that are involved in the control of stamen development and, in particular, pollen formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Plant Growth, and Genotyping

ap3-3 (Jack et al., 1992), nzz-1 (Schiefthaler et al., 1999), and ms1-1 (van der Veen and Wirtz, 1968) mutants, as well as wild-type plants of accession Landsberg erecta, were grown on a soil:vermiculite:perlite mixture under constant illumination at 20°C. T-DNA insertion lines (Supplemental Table S5; Alonso et al., 2003) for selected genes identified in this study were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University). These lines, as well as wild-type plants of accession Columbia, were grown at 24°C in a growth chamber with cool-white fluorescent light under 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle either on soil or on Murashige and Skoog medium containing kanamycin as selective antibiotic. Segregation analysis and genotyping were applied to isolate lines homozygous for a T-DNA insertion. Primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplemental Table S5. Primers LP and RP were used to amplify a wild-type or an insertion allele of a gene in combination with the T-DNA-specific primer LBb1 (5′-GTGGACCGCTTGCTGCAACT-3′). The exact positions of T-DNA insertions in lines SALK_022689 (target gene At2g40850) and SALK_003193 (target gene At5g62320) were determined by sequencing of the resulting PCR products.

Microarray Setup

Microarrays were based on the Arabidopsis Genome Oligo Set version 1.0 (Operon). This set consists of a total of 26,090 oligonucleotides that correspond to 22,361 annotated genes according to The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) genome annotation version 6. Microarrays were manufactured as previously described (Wellmer et al., 2004).

Tissue Collection and Microarray Experiments

Tissue collection for the different biologically independent sets of samples was done on different days but at the same time of day to minimize any diurnal effects on gene expression. For each tissue sample, floral buds from 50 plants were collected. For the analysis of temporal gene expression in ms1 and wild-type flowers, a total of seven tissue samples were generated for each genotype containing floral buds of different developmental stages. To this end, we first removed all flowers in an inflorescence that had progressed beyond stage 13 (the stage when flowers reach maturity). We then collected stage 13 flowers resulting in sample number 1. For the following five samples (nos. 2–6), we collected the next oldest floral buds, pooling two consecutive flowers per sample. The last tissue sample (no. 7) was comprised of the remaining, early stage floral buds and the inflorescence meristem. Total RNA was isolated from all tissue samples using the RNeasy RNA isolation kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Dye-labeled antisense RNA was generated from these total RNA preparations and hybridized to microarrays using a MAUI hybridization system (BioMicro Systems) as previously described (Wellmer et al., 2006). The dyes used for labeling RNA from the individual samples were switched in the replicate experiments to reduce dye-related artifacts.

Data Analysis

Microarrays were scanned with an Axon GenePix 4200A scanner, using the Gene Pix 5.0 analysis software (Axon Instruments). Raw data were imported into the Resolver gene expression data analysis system (Rosetta Biosoftware) and processed as previously described (Wellmer et al., 2006). We adjusted the P values calculated by this software for each experiment using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure as implemented in the Bioconductor multtest package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/bioc/stable/src/contrib/html/multtest.html). Genes were considered as differentially expressed if they showed an absolute FC value of 2 or more between the wild type and a mutant and had been assigned an adjusted P value < 0.05. All analyses in Resolver were done at the so-called sequence level, i.e. data from reporters (probes) representing the same gene were combined.

Data from the analysis of gene expression in floral homeotic mutants (Wellmer et al., 2004) were reanalyzed to allow a meaningful comparison with the datasets reported in this study. To this end, gene annotations for the oligonucleotide probes on the microarrays used for those experiments (which were originally based on version 4 of the Institute for Genomic Research Arabidopsis genome annotation database) were updated using the TAIR genome annotation version 6. To generate an updated list of stamen-expressed genes for the comparison shown in Figure 1B, we analyzed all 1,162 genes that had been previously reported as specifically or predominantly expressed in stamens (Wellmer et al., 2004) with respect to their representation on the Operon microarrays used for this study. Genes that were not represented on these microarrays were removed from the previously reported list. This led to a total of 1,101 genes (see Supplemental Table S1).

For the comparison of the datasets from the analyses of ap3 whole inflorescences (Wellmer et al., 2004) and ap3 early floral buds (this study), shown in Figure 1C, we reanalyzed the former dataset (after reannotation of the probes; see above) and identified differentially expressed genes (see Supplemental Table S1) as outlined above. The clustering analyses shown in Figures 1D and 3 were done using log10-transformed expression ratios. In both cases, the sequences were clustered using a self-organizing map algorithm with cosine correlation as the similarity metric, as implemented in the Resolver analysis system (Rosetta Biosoftware).

For the identification of functionally related genes and of genes involved in the same biological process, we obtained GO predictions from TAIR and then searched for statistically over- or underrepresented GO terms with the program GOToolBox (Martin et al., 2004) using hypergeometric distribution as statistical test and Benjamini and Hochberg correction for multihypothesis testing.

For a further characterization of the identified genes, we used a local installation of the pathway analysis software MAPMAN version 1.4.2. (Usadel et al., 2005) and log10-transformed ratio data from the ms1 experiments as input data.

RNAi

Fragments of the coding region of genes At2g42940 and At1g12080, which did not contain any long stretches with high sequence identity to other known mRNAs in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), were PCR amplified from cDNA using primers At2g42940 forward (5′-TCCAATGAGGAACCATGA-3′) and At2g42940 reverse (5′-TCCTTCGATTGATGAAACC-3′), and At1g12080 forward (5′-GTCCCCGCCGTGACAGAACA-3′) and At1g12080 reverse (5′-CGTCTTTCTCCTCTGTTTTCT-3′), respectively. The resulting PCR products were cloned into the Gateway entry vector PENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) and then sequenced. Subsequently, the fragments were introduced by recombination into the RNAi plant transformation vector pK7GWIWG2 (Karimi et al., 2002) in two different orientations. The resulting plasmids were tested by restriction digests and then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens. A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis plants of accession Landsberg erecta was done using the previously described floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Four independent transformants for the RNAi construct for At2g42940 were obtained, which showed similar mutant phenotypes. In contrast, the five lines obtained for At1g12080 were indistinguishable from the wild type, despite a clear reduction in transcript levels for this gene in the transgenic plants (data not shown).

In Situ Hybridization

cDNA fragments (300–600 bp) with a low degree of sequence identity to other transcripts from Arabidopsis were PCR amplified (see Supplemental Table S7 for primer sequences) and introduced into the TA-cloning vectors pGEM-T-easy (Promega) or pCR-II-TOPO (Invitrogen). The plasmids were linearized and then used as templates for in vitro transcription. Antisense and sense RNA probes were synthesized using a digoxigenin SP6/T7 labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics) and subsequently hydrolyzed to obtain fragments between 150 and 200 nucleotides long.

Flower buds were fixed under agitation at 4°C for 12 h in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (1.3 m NaCl, 70 mm Na2HPO4, 30 mm NaH2PO4) containing 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. After two 30-min washes in PBS buffer, the material was dehydrated at room temperature through an ethanol series. The material was embedded in paraplast (Sigma-Aldrich) and cut with a microtome into 8-μm-thick sections. The sections were positioned on ProbeOnPlus slides (Fisher Scientific) and then deparaffinized and hydrated under RNase-free conditions. Subsequently, the sections were equilibrated in Tris-EDTA buffer (100 mm Tris, pH 8, 50 mm EDTA solution) at 37°C and then treated for 30 min at 37°C with proteinase K (1 μg/mL) in Tris-EDTA solution, postfixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7, for 10 min, and deacetylated with 0.1 m triethanolamine and acetic anhydride, pH 8, for 10 min before dehydration through an ethanol series. For hybridization, the slides were incubated with the specific digoxigenin probes in a hybridization solution containing 50% (v/v) formamide, 0.3 m NaCl, 12 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 1.2× Denhardt's solution (2% Ficoll 400, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 2% bovine serum albumin fraction V), 6 mm EDTA, 12.5% (w/v) dextran sulfate, and 1.25 mg/mL yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) tRNA. After hybridization, the slides were washed twice for 1 h in 0.2× SSC (3 m NaCl, 300 mm Na citrate) at 55°C, then treated at 37°C for 30 min with a RNase-containing solution (20 mg/mL RNase, 0.5 m NaCl, 10 mm Tris, pH 8, 1 mm EDTA) and finally washed again in 0.2× SSC at 55°C for 60 min. Slides were placed in 1× NTE (2.5 m NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 8, 5 mm EDTA) for 10 min and then blocked in 1% (w/v) Boehringer block (Roche Diagnostics) dissolved in 100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl for 45 min, followed by a 45-min incubation in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in 100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100. Probes were detected using an antidigoxigenin antibody to which alkaline phosphatase had been conjugated (Roche Diagnostics). Subsequently, the slides were washed four times for 15 min in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in a solution containing 100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.3% Triton X-100 with gentle agitation. The slides were then equilibrated in a solution containing 100 mm Tris, pH 9.5, 100 mm NaCl, 50 mm MgCl2 for 10 min before the detection step. Western Blue (Promega) was used as substrate and the sections were dehydrated, washed twice in Histoclear (National Diagnostics), and then mounted in Cytoseal 60 medium (Stephens Scientific). Slides were analyzed using an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss).

Real-Time PCR and RT-PCR

Primers used for real-time and RT-PCR (Supplemental Table S6) were designed to amplify 400- to 450-bp (RT-PCR) and 80- to 150-bp (real-time PCR) long fragments of cDNA. The actin-coding genes AtACT2 and AtACT8, which display complementary patterns of expression (making their combined expression profile quasiconstitutive), were used to normalize the mRNA sources (Charrier et al., 2002). Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy RNA isolation kit followed by DNase I treatment (Qiagen) from 100 mg of whole inflorescences of ap3 mutants and wild-type plants, respectively. cDNA was generated from two independent RNA preparations for each genotype using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR was done with an ABI 5700 sequence detection system using SYBR Green chemistry (PE Biosystems). Forty cycles of 95°C for 30 s followed by 60°C for 1 min were applied for amplification. Each reaction was done in triplicate. For RT-PCR, reactions were carried out in a total volume of 25 μL with 0.4 μm primers and 200 μm dNTPs using Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 4 min; 20 to 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; followed by an elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. The amplification products were visualized on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel via ethidium bromide staining.

Microscopy

Flowers of lines SALK_022689 (target gene At2g40850) and SALK_003193 (target gene At5g62320), as well as of Columbia wild-type plants, were harvested and fixed under vacuum at room temperature for 12 h in a 0.05 mm sodium cacodilate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. After washing in cacodylate buffer, the samples were dehydrated through an acetone series and embedded in Spurr low-viscosity epoxy resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Sections were made with a Supernova ultramicrotome (Reichert Jung) using a glass knife. After staining with toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich), the sections were analyzed using an Axioskop microscope (Zeiss). To check pollen viability, anthers were incubated with 0.2 mg/mL fluorescein diacetate in 7% (w/v) Suc for 30 min. Anthers were analyzed using as Axioskop microscope after rinsing in 7% Suc and transferred to a drop of 7% Suc on a glass slide. Dry pollen grains were examined at ambient temperature using a JSM 6340F field emission scanning electron microscope (JOEL). Images were digitally captured at a working distance of 27 mm at 2.0 kV.

Microarray data from this article have been deposited with the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus data repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE8864.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Comparison of microarray datasets.

Supplemental Figure S2. Expression pattern of At2g42940 in stamens of ms1 and wild-type plants.

Supplemental Figure S3. Distribution of selected GO terms in the ms1 dataset.

Supplemental Figure S4. Stage-dependent expression of transcription factor coding genes in developing anthers as derived from the ms1 experiments.

Supplemental Figure S5. Characterization of an RNAi line for gene At2g42940.

Supplemental Table S1. Microarray data and differentially expressed genes.

Supplemental Table S2. Datasets used for comparison and analysis of gene lists (as shown in Fig. 1).

Supplemental Table S3. Analysis of the dataset derived from the ms1 developmental series.

Supplemental Table S4. Genes with known expression in anthers.

Supplemental Table S5. T-DNA insertion lines.

Supplemental Table S6. Primers used for RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR.

Supplemental Table S7. Primers used for generating probes for in situ hybridizations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arnavaz Garda and Beatriz Dias for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. GM45697 to E.M.M.), the Millard and Muriel Jacobs Genetics and Genomics Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (grant nos. 307219/2004–6, 400767/2004–0, and 475666/2004–6 to M.A.-F. and fellowship to A.B.), the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (grant no. E–26/171.332/2004 to M.A.-F. and fellowship to A.B.), the International Foundation for Science (grant no. C/3962–1 to M.A.-F.), the International Basic Sciences Programme (grant no. IBSP/UNESCO–3–BR–28 to M.A.-F.), and Aventis Crop Sciences (fellowship to M.A.-F.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Elliot M. Meyerowitz (meyerow@caltech.edu).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Aarts MGM, Hodge R, Kalantidis K, Florack D, Wilson ZA, Mulligan BJ, Stiekema WJ, Scott R, Pereira A (1997) The Arabidopsis MALE STERILITY 2 protein shares similarity with reductases in elongation/condensation complexes. Plant J 12 615–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht C, Russinova E, Hecht V, Baaijens E, de Vries S (2005) The Arabidopsis thaliana SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASES1 and 2 control male sporogenesis. Plant Cell 17 3337–3349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen HM, Shinn P, Stevenson DK, Zimmerman J, Barajas P, Cheuk R, et al (2003) Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagai M, Ariizumi T, Endo M, Hatakeyama K, Kuwata C, Shibata D, Toriyama K, Watanabe M (2003) Identification of anther-specific genes in a cruciferous model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, by using a combination of Arabidopsis macroarray and mRNA derived from Brassica oleracea. Sex Plant Reprod 15 213–220 [Google Scholar]

- Ariizumi T, Hatakeyama K, Hinata K, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Toriyama K (2005) The HKM gene, which is identical to the MS1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana, is essential for primexine formation and exine pattern formation. Sex Plant Reprod 18 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum K, Jung JW, Wang JY, Lambert GM, Hirst JA, Galbraith DW, Benfey PN (2005) Cell type-specific expression profiting in plants via cell sorting of protoplasts from fluorescent reporter lines. Nat Methods 2 615–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz JO, Xia YJ, Blount J, Dixon RA, Lamb C (2000) Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 12 2383–2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales C, Bhatt AM, Scott R, Dickinson H (2002) EXS, a putative LRR receptor kinase, regulates male germline cell number and tapetal identity and promotes seed development in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 12 1718–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson S, Spencer M, Walker K, Lindsey K (2005) Laser capture microdissection for the analysis of gene expression during embryogenesis of Arabidopsis. Plant J 42 111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier B, Champion A, Henry Y, Kreis M (2002) Expression profiling of the whole Arabidopsis Shaggy-like kinase multigene family by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Plant Physiol 130 577–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnudde F, Moretti C, Porceddu A, Pezzotti M, Gerats T (2003) Transcript profiling on developing Petunia hybrida floral organs. Sex Plant Reprod 16 77–85 [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J, Wilson ZA, Aarts MGM, Braithwaite AF, Briarty LG, Mulligan BJ (1993) Microspore and pollen development in 6 male-sterile mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Can J Bot 71 629–638 [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, Engler JD, Miguens FC, VanMontagu M, Engler G, deOliveira DE (1997) Oleosin gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana tapetum coincides with accumulation of lipids in plastids and cytoplasmic bodies. Plant Physiol Biochem 35 729–739 [Google Scholar]

- Gocal GFW, Sheldon CC, Gubler F, Moritz T, Bagnall DJ, MacMillan CP, Li SF, Parish RW, Dennis ES, Weigel D, et al (2001) GAMYB-like genes, flowering, and gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 127 1682–1693 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg RB, Beals TP, Sanders PM (1993) Anther development: basic principles and practical applications. Plant Cell 5 1217–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Mena C, de Folter S, Costa MMR, Angenent GC, Sablowski R (2005) Transcriptional program controlled by the floral homeotic gene AGAMOUS during early organogenesis. Development 132 429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greb T, Mylne JS, Crevillen P, Geraldo N, An HL, Gendall AR, Dean C (2007) The PHD finger protein VRN5 functions in the epigenetic silencing of Arabidopsis FLC. Curr Biol 17 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginson T, Li SF, Parish RW (2003) AtMYB103 regulates tapetum and trichome development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 35 177–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys D, Twell D (2003) Comparative analysis of the Arabidopsis pollen transcriptome. Plant Physiol 132 640–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys D, Twell D (2004) Transcriptome analysis of haploid male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol 5 R85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K, Huang AHC (2007) Tapetosomes in Brassica tapetum accumulate endoplasmic reticulum-derived flavonoids and alkanes for delivery to the pollen surface. Plant Cell 19 582–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Shinozaki K (2002) The MALE STERILITY1 gene of Arabidopsis, encoding a nuclear protein with a PHD-finger motif, is expressed in tapetal cells and is required for pollen maturation. Plant Cell Physiol 43 1285–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack T (2004) Molecular and genetic mechanisms of floral control. Plant Cell 16 S1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack T, Brockman LL, Meyerowitz EM (1992) The homeotic gene APETALA3 of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a MADS box and is expressed in petals and stamens. Cell 68 683–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen MK, Poulsen LR, Schulz A, Fleurat-Lessard P, Moller A, Husted S, Schiott M, Amtmann A, Palmgren MG (2005) Pollen development and fertilization in Arabidopsis is dependent on the MALE GAMETOGENESIS IMPAIRED ANTHERS gene encoding a type VP-type ATPase. Genes Dev 19 2757–2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Han MJ, Lee YS, Kim YW, Hwang I, Kim MJ, Kim YK, Nahm BH, An G (2005) Rice undeveloped tapetum1 is a major regulator of early tapetum development. Plant Cell 17 2705–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Inze D, Depicker A (2002) GATEWAY(TM) vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci 7 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroj T, Savino G, Valon C, Giraudat J, Parcy F (2003) Regulation of storage protein gene expression in Arabidopsis. Development 130 6065–6073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Udagawa M, Nishikubo N, Horiguchi G, Yamaguchi M, Ito J, Mimura T, Fukuda H, Demura T (2005) Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev 19 1855–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin JC, Brown ML, Schiefelbein J (2003) How do cells know what they want to be when they grow up? Lessons from epidermal patterning in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54 403–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]