Abstract

Patients with long term symptoms, lack of a scientific explanation, and insurance companies' reluctance to pay for treatment have created a perfect breeding ground for dissent, Alison Tonks reports

Lyme disease is a simple bacterial infection spread by ticks. There is a fairly characteristic rash, a well documented pattern of symptoms, and a safe effective treatment. But in the US, Lyme disease is at the centre of a long running and bitter controversy. It is no longer a disease but a legal and political battleground. At the core of the disagreement is the possibility that the Lyme bacterium could survive initial treatment, evade detection, and cause disabling symptoms for months or even years. A growing and vociferous patient lobby thinks it can. Mainstream medical opinion thinks it can't. Why does it matter? Because those who believe in chronic infection also believe in long term treatments, including repeated or prolonged courses of antibiotics that doctors are reluctant to prescribe and insurance companies are reluctant to pay for.

The trigger

The latest exchange of fire between the two sides was triggered by official treatment guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.1 An update at the end of last year repeated that there was no evidence for existence of chronic infection, then listed 12 treatments that doctors ought not to give patients with Lyme disease. Long term antibiotics were on the list, alongside “hyperbaric oxygen, ozone, fever therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, cholestyramine, intravenous hydrogen peroxide, [and] specific nutritional supplements.”1

Lyme advocacy organisations such as the Lyme Disease Association and the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society dismiss the wackier treatment options such as fever therapy (hyperthermia), bee venom, and antioxidants, but both strongly support the option of long term or repeated courses of antibiotics for some patients.2 They argue that the update effectively blocks access to treatments by giving insurance companies a good excuse to stop paying for them. An excuse they have been quick to exploit, according to Pat Smith, president of the Lyme Disease Association. “Even pharmacies are now refusing to fill prescriptions for antibiotics not recommended by the latest update,” she says.

The challenge

The Lyme lobby has recruited some powerful allies. Arguably the most powerful is Connecticut's attorney general, Richard Blumenthal. He is an elected official and “the public's lawyer” in a state crawling with infected ticks. Late last year his office launched an unprecedented investigation, alleging the Infectious Diseases Society's updated guidelines breached anti-trust legislation.

Anti-trust laws are designed to “promote competition and level the playing field in [our] marketplace,” according to the attorney general's website. His office is investigating whether the guidelines are anticompetitive and unfair, denying healthcare providers legitimate income by denying patients legitimate forms of treatment.

The attorney general takes a close interest in Connecticut's Lyme disease problem. His state has the highest incidence of reported cases in the US.3 In 2004, he colourfully described the infection as “a disease that is pernicious, insidious, immensely destructive, costly to our state, and particularly to our children”4 and warned that no one should be complacent, even in the coldest weather. “The ticks that carry this disease may be resting under the snow.”

Ms Smith applauds the attorney general's pioneering investigation. She says the action is “vitally necessary to protect the welfare of chronic Lyme patients nationwide” and that the guidelines “are being used to deny treatment reimbursement and will have a continued chilling effect on the small numbers of treating physicians, since clinical discretion is not recommended in the guidelines.”5 She said, “Sick patients have a right to more treatment if they relapse, or if their symptoms don't resolve. There may be gaps in the evidence, but it's wrong to leave patients hanging in the wind while you try to fill those gaps.”

The Infectious Diseases Society naturally takes a different view. Clinical guidelines are not mandatory and cannot replace individual doctors' judgment, says the president Henry Masur. “The debate on how best to treat Lyme disease is a scientific one, and we believe it is best resolved scientifically. [This challenge] threatens the role of all professional societies to educate their members and the public about best medical practices.”6 In an unusual move, the guidelines include a clear statement that the recommendations are voluntary.

The society's lawyers say an anti-trust claim probably wouldn't succeed. But the society has already spent thousands of dollars cooperating with the investigation. And they may have to spend many thousands more.

The politics

The adversarial politics of Lyme disease are not confined to Connecticut. State governments in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts are already considering bills that would sanction long term antibiotic therapy for chronic Lyme disease. Pennsylvania's bill would also require insurance companies to pay for it. Both bills are pending. The Lyme Disease Association openly and enthusiastically supports the use of state laws to increase treatment options for patients. Political activism is their core territory. “Legislation is one of the most powerful advocacy tools available to the Lyme community” according to an article on its website.7

Hard line political activism often puts them in direct conflict with the majority of infectious disease specialists. In August, Dr Masur wrote to the chairman of the National Governors Association, warning of the damaging effects of misguided legislation. Long term antibiotics can be dangerous for patients and indirectly for everyone else by increasing the likelihood of resistant super bugs.8

The disease

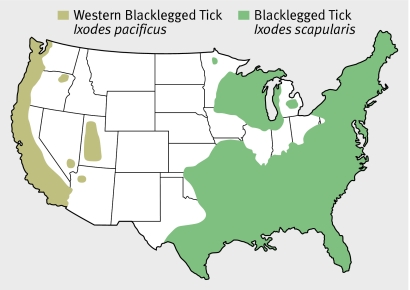

In the US, acute Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is carried and spread by infected ticks endemic to many states.9 Some, but not all, patients develop a characteristic spreading rash called erythema migrans. The rash is accompanied by muscle aches and pains, arthralgia, headache, fatigue, and sometimes a fever. Left untreated, the spirochete can spread to joints (causing arthritis), nerves (facial nerve palsy is the commonest manifestation), and the heart (causing heart block).9 10 Several antibiotics, including oral doxycycline, kill the spirochete. Most treated patients get better after a course of no more than one month.1

US distribution of tick vectors for Lyme diseases9

Controversy arises over treatment of people who don't respond to short courses of antibiotics. Up to one in six patients with erythema migrans still has fatigue, myalgia, or arthralgia a year after the rash has gone. About one in ten still has non-specific symptoms five years after their original treatment.10 The Lyme lobby believe these and other non-specific symptoms, including paraesthesias and disturbances of mood and memory, could be caused by persisting infection with live organisms. The mainstream view is that chronic symptoms are caused by something else.11

Jonathan Edlow, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, lists among the possibilities permanent tissue damage caused by the initial infection, persistent inflammation not driven by live infection, some kind of autoimmune process, or a second illness triggered by Lyme disease such as anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, or chronic fatigue syndrome. None of these would respond to further antibiotics. Many believe chronic Lyme disease is simply the latest in a long line of convenient labels for people with enduring non-specific symptoms that are hard to explain and challenging to treat. “Chronic candida syndrome” and “chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection” have both come and gone.11

The ammunition

The two sides of the controversy have never seen eye to eye, but over the past decade, the accusations and counter accusations have become increasingly belligerent and entrenched. Mainstream specialists characterise doctors sympathetic to the Lyme camp as self serving mavericks who prescribe prolonged courses of expensive antibiotics to make money from desperate patients, or from drug company backhanders. Patient advocates both inside and outside the profession accuse the main stream of being Lyme deniers who control the research agenda, the conference circuit, and the editorial boards of the main medical journals and who in turn accept consulting fees from insurance companies unwilling to pay out for long term treatments.

Both sides accuse each other of cherry picking the evidence to match their point of view, although mainstream opinion takes a harder line on acceptable kinds of evidence. Much is made, for example, of a paper published by the New England Journal of Medicine in 2001 which reported that prolonged antibiotic treatment doesn't work.12 The paper actually reported two small randomised controlled trials in a total of 129 patients with chronic symptoms after documented infection with the Lyme spirochete. Both trials were stopped early because an interim analysis showed that 90 days of treatment with intravenous followed by oral antibiotics had no effect on their quality of life.

The two sides are still arguing over the interpretation of these trials, which were small and included carefully selected patients. They are also still arguing about much of the other largely anecdotal evidence published about Lyme disease.

Disagreements are perhaps not surprising. Infection causes common non-specific symptoms (fatigue, muscle aches and pains, joint pain, stiff neck). Diagnosis is subjective. The only physical sign (erythema migrans) occurs with at least one other tick borne disease,9 is highly variable in appearance, and may even be absent. Many people don't remember being bitten by a tick because the nymphs that commonly spread Lyme disease are too small to be noticeable. Blood tests for antibodies are unreliable, particularly in the long term. Other tests such as skin biopsies and culture are too cumbersome for the bed side. So in practice the diagnosis is almost always clinical. To complicate things further, the tick responsible for Lyme disease also transmits other infections that can coexist alongside the Lyme spirochete in a single host.10

The diagnostic vacuum has naturally been filled by commercial companies offering various unvalidated tests, including urine tests for B burgdorferi antigens and blood tests for DNA. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has already warned doctors not to use these tests and urged patients to demand that their blood tests are approved and scientifically validated.13 The trouble is, the official diagnostic line (see box) is already 10 years old and anyway cannot rule out persisting infection in patients with persisting symptoms. Nothing can.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for diagnosis of Lyme disease14

No tests are recommended for patients with a typical pattern of symptoms that includes erythema migrans

Atypical patients should have a blood sample tested by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

If the first ELISA result is negative, no further tests are done. The patient is seronegative

If the ELISA result is positive or equivocal, the same sample is retested using Western immunoblot analysis. A patient is seropositive if both tests are positive

The immunoblot analysis must be interpreted by staff at a qualified laboratory that follows CDC guidelines. Immunoblot analysis is not recommended in isolation because of the risk of a false positive result.

Patients in the early stages of Lyme disease may still be seronegative and should be retested during the convalescent phase

Evidence based medicine has nothing to offer in the diagnosis and treatment of patients who think they may have chronic Lyme disease. A few doctors are willing to take them on, but these doctors are often harassed by their peers and the medical licensing authorities. These patients are hard work, says Ms Smith. “History taking alone can take hours, and there isn't a convenient cook book to follow for treatment. They need months or years of follow-up.”

To many doctors this sounds like familiar heartsink territory. But these are heartsink patients with a difference. They have a voice, they have friends in high places, and they have money. Earlier this year, funds from the Lyme Disease Association opened a new research centre for Lyme and tick borne diseases at Columbia University.

Beginnings of a resolution

It's hard to know how the current acrimonious stand off will end, but both sides are beginning to show signs of battle fatigue. Even the most entrenched observer can see that mud slinging, muck raking, intimidation, and professional isolation is no way to conduct a scientific inquiry—particularly when vulnerable people are caught in the cross fire.

Fortunately, common ground is not hard to find for those willing to pause and look up from the fighting. A careful examination of guidelines from the two camps shows that both sides are working towards the same goals—a better scientific understanding of this complex infection, standardised definitions, reliable tests, and more, bigger, and better trials of treatment for early and late disease.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere AC, Klempner MS, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1089-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron D, Gaito A, Harris N, Bach G, Bellovin S, Bock K, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of Lyme disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2004;2(1 suppl):S1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connecticut Department of Public Health. Lyme disease 26 Sep 2007. www.ct.gov/dph/cwp/view.asp?a=3136&pm=1&Q=395590&dphNav_GID=1601

- 4.State of Connecticut Attorney General's Office. Verbatim proceedings of a public hearing of the State of Connecticut. Department of Public Health, In Re: Lyme Disease, held January 29, 2004 at 9:00 am www.ct.gov/ag/lib/ag/health/0129lyme.pdf

- 5.Lyme Disease Association. Historic move by CT attorney general to investigate IDSA guidelines process Press release 16 Nov 2006. www.Lymediseaseassociation.org/NewsReleases/20061116.html

- 6.Infectious Diseases Society of America. From the President: IDSA stands up for lyme disease guidelines. IDSA News 2007;17(2). www.idsociety.org/newsArticle.aspx?id=4262

- 7.Smith P. State legislation in the limelight www.Lymediseaseassociation.org/LegHowTo.html

- 8.Masur H. Letter to chairman of Health and Human Services Committee National Governors Association, 7 Aug 2007. www.idsociety.org/WorkArea/showcontent.aspx?id=6452

- 9.Tibbles CD, Edlow JA. Does this patient have erythema migrans? JAMA 2007;297:2617-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wormser GP. Early Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2794-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feder HM, Johnson BJB, O'Connell S, Shapiro ED, Steere AC, Wormser GP. A critical appraisal of chronic Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1422-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, Schmid CH, Johnson GM, Trevino RP, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med 2001;345:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Notice to readers: caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. MMWR 2005;54:125 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notice to readers: recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the second national conference on serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 1995;44:590-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]