Abstract

Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) is expressed in both pulp and odontoblast cells and deletion of the Dmp1 gene leads to defects in odontogenesis and mineralization. The goals of this study were to examine how DMP1 controls dentin mineralization and odontogenesis in vivo. Fluorochrome labeling of dentin in Dmp1-null mice showed a diffuse labeling pattern with a three-fold reduction in dentin appositional rate compared to controls. Deletion of DMP1 was also associated with abnormalities in the dentinal tubule system and delayed formation of the third molar. Unlike the mineralization defect in Vitamin D receptor null mice, the mineralization defect in Dmp1-null mice was not rescued by a high calcium and phosphate diet, suggesting that the effects of DMP1 on mineralization are locally mediated. Re-expression of Dmp1 in early and late odontoblasts under control of the Col1a1 promoter rescued the defects mineralization as well as the defects in the dentinal tubules and third molar development. In contrast, re-expression in mature odontoblasts, using the Dspp promoter, produced only a partial rescue of the mineralization defects. These data suggest that DMP1 is a key regulator of odontoblast differentiation, formation of the dentin tubular system and mineralization and its expression is required in both early and late odontoblasts for normal odontogenesis to proceed.

Keywords: DMP1 transgenic mice, odontogenesis, dentin apposition rate, tooth development, mineralization

INTRODUCTION

Dentin, formed by odontoblasts, is a mineralized tissue that shares some common characteristics with bone in its composition and mineralization processes. It is widely believed that mineralization is initiated by phosphorylated extracellular matrix proteins localized within collagen gap zones that bind calcium and phosphate ions in an appropriate conformation to nucleate the formation of apatite crystals (Glimcher, 1989; Hunter et al., 1996). However, collagen alone does not spontaneously mineralize in metastable calcium phosphate solution (Saito et al., 2001). Many non-collagenous proteins, which are expressed in odontoblasts, have been proposed to play important roles in this process (Saito et al., 2001). These proteins include osteopontin (Denhardt and Noda, 1998; Fujisawa et al., 1993; Qin et al., 2001; Yoshitake et al., 1999), bone sialoprotein (Chen et al., 1992; Fisher et al., 1983; Fujisawa et al., 1993; Lowe et al., 1993; Shapiro et al., 1993), osteonectin (Papagerakis et al., 2002; Reichert et al., 1992), osteocalcin (Gorski, 1998; Qin et al., 2001), BAG-75 (Gorski, 1998; Qin et al., 2001), dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) (D’Souza et al., 1997; Feng et al., 1998; MacDougall et al., 1997) and DMP1 (Feng et al., 2003; Feng et al., 2002; George et al., 1993).

DMP1, an acidic phosphorylated extracellular matrix protein, was mapped to mouse chromosome 5q21(George et al., 1994) and human chromosome 4q21:22 (MacDougall et al., 1996). These chromosomal regions contain a superfamily gene locus of related acidic dentin and bone phosphoproteins that are of potential importance during the process of bio-mineralization (MacDougall et al., 1998). DNA sequence analysis has revealed that the DMP1 protein is rich in aspartic acid, glutamic acid and serine and has numerous potential phosphorylation sites for casein kinases I and II. A potential RGD cell attachment sequence and a consensus sequence for N-glycosylation have also been identified. Initial in situ hybridization and Northern data suggested that this gene was odontoblast specific (George et al., 1993; George et al., 1995). However, more recent in situ hybridization and Northern blot studies from our laboratory and others have shown that Dmp1 is also expressed in bone (D’Souza et al., 1997; Feng et al., 2002; Hirst et al., 1997; MacDougall et al., 1996; Narayanan et al., 2003) and cartilage (Feng et al., 2002).

George and coworkers showed that overexpression of DMP1 in vitro induces differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells and enhances mineralization (Narayanan et al., 2001a). They also reported that DMP1 was mainly localized in the nucleus of MC3T3-E1 cells (preosteoblast-like cell line) and that the DMP1 protein contained a functional nuclear localization signal sequence at residues 472–481. Mutations at this site led to intense cytoplasmic accumulation of the labeled protein and impeded the interaction of DMP1 with α-importin, a soluble transport factor. Thus they proposed that DMP1 had dual functions, both as a transcription factor that targeted the nucleus and as an extracellular matrix protein that initiated mineralization (Narayanan et al., 2003). On the other hand, Boskey and her colleagues showed that the roles of DMP1 in initiation or inhibition of mineralization in vitro depend on the phosphorylation and forms of DMP1 (Tartaix et al., 2004).

Dmp-null newborns displayed no apparent phenotype (Feng et al., 2003), but develop hypomineralized bone phenotype (Ling et al., 2005), defects in cartilage formation (Ye et al., 2005), and hypophosphatemia rickets with elevated FGF23 concentrations (Feng et al., 2006, in Nature Genetics online publication) during postnatal development. Mutational analyses revealed that autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia patients carried a mutation that ablated the DMP1 start codon or exhibited deletion of nucleotides in the highly conserved DMP1 C-terminus (Feng et al., 2006 in Nature Genetics online publication).

Previously we reported that mice null for the Dmp1 gene displayed a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization of the dentin, as well as expansion of the pulp cavities and root canals during postnatal tooth development. These data suggest that DMP1 is a critical regulator of mineralization and dentinogenesis in vivo. However, the in vivo mechanisms by which DMP1 controls odontogenesis and mineralization are currently unknown (Ye et al., 2004).

To determine whether DMP1 alters the rate of dentin apposition in vivo, in this study we used a fluorochrome labeling assay for quantitation of dentin apposition rate. These studies showed that the mineralization rate was reduced almost threefold in Dmp1-null mice compared to controls. To determine when in the odontogenesis pathway the action of DMP1 is required we generated transgenic mice overexpressing DMP1 under control of either the 3.6 kb Col 1a1 or the 6 kb Dspp promoter fragment. The 3.6 Col1a1 promoter, which we have termed the “early” promoter, drives Dmp1 expression in pulp and odontoblast cells. In contrast, the 6kb Dspp promoter, which we have termed the “late” promoter, drives Dmp1 expression in mature odontoblasts. These transgenic mice were used to determine the effect of overexpression of DMP1 on a wild type background as well as to determine the effect of re-expression of DMP1 at specific stages of odontoblast maturation on the Dmp1-null background. These approaches have revealed that DMP1 is a key regulator of both odontoblast differentiation and mineralization during dentin formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Dmp1 transgenic mice

For generation of a DMP1 “early” transgene that is expressed in pulp cells and early odontoblasts, a cDNA fragment covering the full-length coding region of the murine Dmp1 and an SV40 later poly A tail was cloned into a mammalian expression vector (Braut et al., 2002) (a gift provided by B. Kream and Alex Lichtler, University of Connecticut Medical Center) containing 3.6 kb rat type I collagen promoter plus a 1.6 kb intron 1 at EcoR V and Sal I sites, giving rise to the Col 1-Dmp1 transgene. For the generation of a DMP1 “late” transgene that is expressed in mature odontoblasts, the same Dmp1 cDNA was blunt end ligated into the pBS II SK+ vector (Sreenath et al., 1999) containing a 6 kb Dspp promoter-intron I region at the Nru I site, giving rise to a Dspp-Dmp1 transgene. This vector was provided by T. L. Sreenath from the functional genomics unit/NIDCR/NIH. Transgenic founders with CD-1 background were generated by pronuclear injection according to standard techniques. Two out of four independent founders from the Col 1-Dmp1 transgene construct and two out of seven independent founders from the Dspp-Dmp1 transgene construct were used for crossing to Dmp1 null mice (see below).

Expression of Dmp1 transgene in Dmp1-null mice

We have previously described the generation of mice null for Dmp1 using the lacZ knock-in targeting approach (Feng et al., 2003). For re-expression of DMP1 in mice lacking Dmp1, breeding was performed using homozygous Dmp1 null males (viable) and Col 1-Dmp or Dspp-Dmp1 female mice that were heterozygous for the Dmp1 null allele mice to produce Dmp1-null mutants carrying the early or late Dmp1 transgene. (It is of note that female Dmp1-null mice are fertile but produce smaller litter sizes compared to wild type or heterozygous females). As no phenotypic differences between the wild type mice and heterozygous Dmp1-null mice were found (Ye et al., 2004), the heterozygous Dmp1- null mice were used for the control. Five developmental stages were analyzed. Samples were obtained from newborn, 10-day-old, 3-week-old, 1-month-old, and 2- month-old mice for this study. All mice were bred to CD-1 background (for over 6 generations). The animal research has complied with all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies. Statistical differences between groups were assessed either by Student’s t-test or by ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test.

PCR genotyping

Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from the tail using primers p01 (5′-CTTGACTTCAGGCAAA TAGTGACC-3′) and p02 (5′-GCGGAA TTCGATAGCTTGGCTG-3′) for detection of the null Dmp1 allele (280 bp), and primers p01 (5′-CTTGACTT CAGGCAAATAGTGACC-3′ and p03 5′-CTGTTCCTCACTCTCACTGTCC-3′) for detection of the wild-type allele (410 bp). The primers p04 (5′-CAGCCGTT CTGAGGAAGACAGTG-3′ from Dmp1 cDNA) and p05 (5′-TGTCCAAA CTCATCAATGTATCT-3′, from SV40 poly A) were used for detection of the transgene for Col 1-Dmp1 or Dspp-Dmp1, giving rise to a ~400 bp fragment.

Vitamin D receptor (VDR)-null mice

We have previously described the generation of mice null for VDR using gene targeting approaches (Li et al., 1997). In this experiment mandibles were isolated from the 2-month-old wild type and VDR null mice with a CD-1 and C57B6 mixed background.

High calcium and phosphate diet

To determine whether a high calcium/phosphate diet could rescue the tooth phenotypes observed in Dmp1-null mice, the mice were either fed ad libitum on regular rodent chow (containing 1% calcium and 0.7% phosphate) or on a high calcium, high lactose diet containing 2% calcium, 1.5% phosphate, and 20% lactose (TD96348, Teklad, Madison, WI). This diet has previously been shown to normalize blood-ionized calcium levels in VDR-null mice (Li et al., 1998).

High resolution radiography of the teeth and mandible

To obtain high resolution radiographs of the mouse teeth, the first and third molars were extracted as described previously (Ye et al., 2004). Briefly, fresh mandibles were incubated in lysis buffer (2x SSC, 0.2% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mg/ml Proteinase K) for 1–2 days. After the muscles surrounding teeth were digested, the mandibles were washed in 1x phosphate-buffered saline, and molars were extracted under a dissection microscope. The intact mandibles and isolated first and third molars were then X-rayed on a Faxitron model MX-20 Specimen Radiography System with a digital camera attached (Faxitron x-ray Corp., Buffalo Grove, IL).

Resin casted scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Mandibles were dissected, fixed in 2% para-formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer solution (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 4 h and then transferred to 0.1 M cacodylate buffer solution. The tissue specimens were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (from 70% to 100%), embedded in methyl-methacrylate (MMA, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL), and the surface polished using 1 micron and 0.3 micron alumina alpha micropolish II solution ( Buehler) in a soft cloth rotating wheel. The dentin surface was acid etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 2–10 seconds, followed by 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes. The samples were then coated with gold and palladium as described previously (Martin et al., 1978), and examined using an FEI/Philips XL30 Field emission environmental scanning electron microscope (Hillsboro, OR).

Colloidal gold immunolabeling for DMP1 and transmission electron microscopy

For high-resolution ultra-structural immunocytochemistry, hemi-mandibles from 1 month-old mice were fixed overnight by immersion in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde. After decalcification for 2 weeks in 4% EDTA (pH 7.3) under constant agitation at 4ºC, samples were dehydrated through graded ethanols, and embedded in LR White acrylic resin (London Resin Company, Berkshire, UK). One-micrometer-thick survey sections were cut in the molar regions, perpendicular to the long axis of the hemi-mandible, using a Reichert Ultracut E ultramicrotome. Sections were stained on glass slides with toluidine blue for light microscopy, and selected areas were chosen for thin sectioning (80–100 nm). Thin sections were placed on Formvar™- and carbon-coated nickel grids for colloidal-gold immunocytochemistry and transmission electron microscopy. Post-embedding immuno-gold labeling for DMP1 was performed on grid-mounted thin sections as described previously (McKee and Nanci, 1995) using anti-rat DMP1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (courtesy of Dr. W. T. Butler) followed by protein A-gold (14 nm-diameter gold particles; Dr. G. Posthuma, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands). Briefly, grid-mounted tissue sections were floated for 5 minutes on a drop of 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% ovalbumin (Sigma) and then transferred and incubated for 1 h at room temperature on a drop of rabbit anti-DMP1. After this primary incubation, sections were rinsed with PBS, placed again on PBS-1% ovalbumin for 5 minutes, followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature with the protein A-gold complex. Tissue sections were then washed thoroughly with PBS, rinsed with distilled water, air dried, routinely stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed by transmission electron microscopy. Control immunocytochemical incubations consisted of substituting the primary antibody with non-immune rabbit serum or with irrelevant polyclonal antibody, or omitting the primary antibody and using protein A-gold alone. Morphological observations and immunogold labeling patterns were recorded using a JEOL 2000FXII transmission electron microscope operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

Visualization of the dentin tubules by procion red

This small molecular dye was injected ten minutes prior to sacrifice through the tail vein (0.8 % procion red in sterile saline, 10μl per gram body weight) under anesthesia by Avertin (5 mg/kg body weight). After sacrifice, the mandibles were fixed in 70% ETOH followed by dehydration and embedded using a standard epoxy method (Knothe Tate et al., 2004). The specimens were sectioned at 100 μm thickness using a Leitz 1600 saw microtome. The specimens were then viewed under a Nikon C100 confocal microscope (Nikon, USA) and photographed using an Optronics cooled CCD camera.

Double fluorochrome labeling of the teeth

To analyze the changes in dentin apposition rate, double fluorescence labeling was performed as described previously with a minor modification (Miller et al., 1985). Briefly, a calcein label (5 mg/kg i.p.; Sigma-Aldrich) was administered to 24-day-old mice. This was followed by injection of an Alizarin Red label (20 mg/kg i.p.; Sigma-Aldrich) 5 days later. Mice were sacrificed 48h after injection of the second label, and the mandibles were removed and fixed in 70% ethanol for 48 h. The specimens were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (70–100%) and embedded in MMA without prior decalcification. One hundred μm sections were cut using a Leitz 1600 saw microtome. The unstained sections were viewed under epifluorescent illumination using a Nikon E800 microscope, interfaced with the Osteomeasure histomorphometry software (version 4.1, Atlanta, GA). Using this software, the mean distance between the two fluorescent labels was determined and divided by the number of days between labels to calculate the apposition rate (μm/day). These analyses were performed on the lower first molars.

In situ Hybridization

The digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled mouse cRNA probes of Dmp1 (0.5 Kb) and Osterix (0.6 kb, a gift from S.E. Harris, UT Health Science Center at San Antonio, TX) were prepared with the use of an RNA Labeling Kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). In situ hybridization on paraffin sections was carried out essentially as described previously (Feng et al., 2002). The hybridization temperature was set at 55°C, and washing temperature at 70°C so that endogenous alkaline phosphatase (AP) would be inactivated. DIG-labeled nucleic acids were detected in an enzyme-linked immunoassay with a specific anti-DIG-AP antibody conjugate and an improved substrate that gives rise to a red signal (Vector, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunocytochemistry

Deparaffinized long-bone sections were stained as described previously (Ye et al., 2004) with a rabbit anti-rat DMP1 peptide polyclonal antibody made to the N-terminal peptide 90–111.

RESULTS

Disruption of Dmp1 leads to abnormalities in mineralization and ultrastructure of dentin

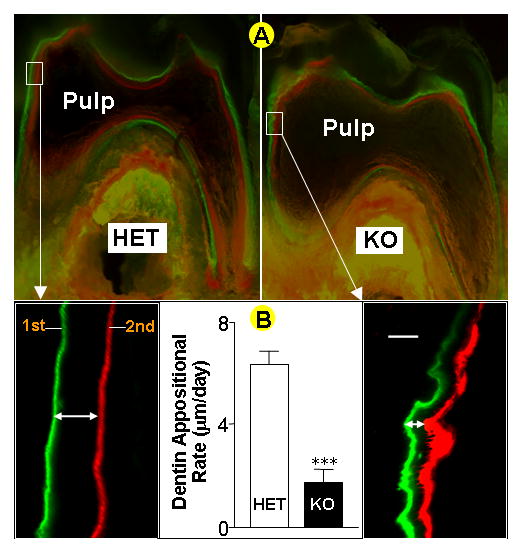

Previously we reported a hypomineralized phenotype in the dentin of Dmp1-null mice, as reflected by increased width of the predentin zone and reduced thickness of the dentin wall (Ye et al., 2004). However, it was not clear if this defect is due to a failure in initiation of mineralization or to a reduced rate of mineralization. To address this question, the dentin apposition rate was measured using the fluorochrome labeling assay (Miller et al., 1985). Fig 1A shows fluorochrome labeling of heterozygous control (left) and Dmp1 KO (right) mice injected with calcein on post natal day 24, followed by an injection of alizarin red at day 29 and sacrifice 2 days later. In control mice, there are two discrete lines of labeling. The distance between the two lines reflects the dentin formation rate at ~7 μm/day (Fig 1a, left lower panel). In the Dmp1 KO mice the fluorochrome labeling lines appear thicker, wavy, and more diffuse than controls (Fig 1A, right lower panel) and the distance between the labeling lines is significantly reduced, resulting in an appositional rate of less than 2 μm/day (Fig 1B). Thus in the Dmp1-null mice the appositional rate appears to be reduced more than three-fold compared to controls, suggesting that changes of the apposition rate might have resulted from a disorganization of odontoblast layer.

Fig. 1. Dentin mineral apposition rate is reduced in Dmp1-null mice.

Panel A, fluorochrome labeled sections of the lower first molar from heterozygous control (HET, left, and inset) and Dmp1 knockout mice (KO, right, and inset) reveal a reduction of the dentin mineralization rate in the knockout mice . Bar = 10μm. Panel B, quantitative analysis shows a significant difference in the dentin appositional rate between the control and the KO in the first molar (data are mean ± SEM from n=4 replicates, *** = p< 0.001 by Student’s t-test)

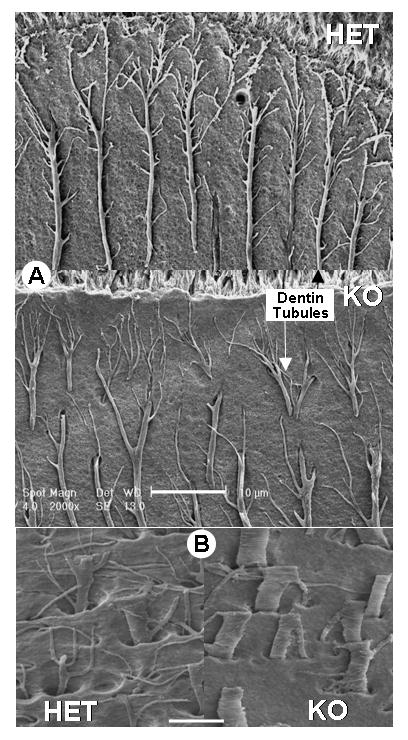

To determine whether deletion of DMP1 also changes the dentin ultrastructure, we next examined the dentin of Dmp1-null mice by scanning electron microscopy using an acid-etched resin casting technique (Martin et al., 1978) (Fig 2). In this technique, polished surfaces of the resin embedded dentin were etched with acid to remove mineral, leaving a relief cast of the non-mineralized areas that have been infiltrated by resin. This technique therefore shows the morphology of the dentin tubular system. Striking differences were observed in the appearance of the dentin tubules from Dmp1-null mice compared to age-matched controls, with the tubular processes appearing disorganized and less branched. These observations suggest that DMP1 plays a major role in establishing the correct architecture and organization of the dentin tubular system, either as a secondary consequence of its effects on mineralization or through a direct effect of DMP1 on dentin tubule formation.

Fig. 2. Abnormal morphology of the dentinal tubules in Dmp1-null mice.

Panel A, shows resin-casted SEM images of the dentinal tubules in heterozygous control (HET, upper panel) and Dmp1 knockout mice (KO, middle panel). Note that the tubules in the KO mice appear more disorganized and show less branching that in controls. Bar = 10μM. Panel B, shows a higher magnification view in which it is clear that the dentin tubules in Dmp1-null mice (KO, lower right panel) are flatter, wider and less branched compared to controls (HET, lower left panel). Bar = 5μM.

Consistent with a potential role for DMP1 in formation of the dentin tubules, Butler and co-workers showed by immunogold EM that in the tooth, DMP1 is predominantly localized in the walls of the dentin tubules (Butler et al., 2002). Thus DMP1 is ideally located to play a role in dentin tubule formation.

The dentin phenotype in Dmp1-null mice is a unique model and appears to have a different mechanism than that caused by deletion of the Vitamin D receptor (VDR)

Abnormalities in the dentin tubular system in Dmp1-null mice could be due to direct effects of DMP1 on dentine tubule formation and/or maintenance or they may occur as a secondary consequence of the impairment in mineralization. To address this question, we next compared the properties of dentin tubules in Dmp1-null mice to those in the VDR-null mouse, a classic animal model of osteomalacia (Zheng et al., 2004).

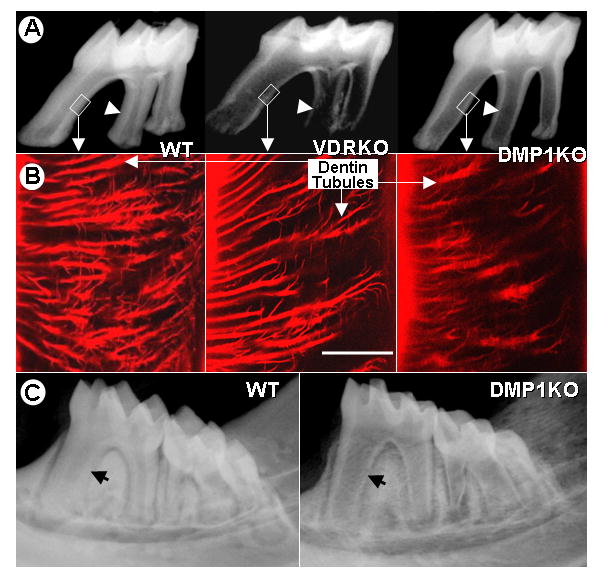

Compared to age matched Het controls (left), dentin from 2 month old VDR-null (middle) and Dmp1-null (right) mice showed a similar thin dentin wall, as demonstrated by high resolution radiographs (Fig 3A). This confirms that there is a similar defect in dentin mineralization in VDR KO mice compared to Dmp1-null mice. Next, we injected procion red, a small molecular dye that penetrates the dentin tubules to provide a visual representation of the organization of the dentin tubular system. Fig 3B shows that in control mice the dentin tubules are highly organized, extensively branched and spaced regularly (left). There appears to be no obvious change in the dentin tubules of VDR-null mice (middle) compared to wild type. In contrast, the dentin tubules in Dmp1-null mice (right) are fewer in number, less branched, and appear disorganized, similar to our observations using the acid etched resin cast technique (Fig 2).

Fig. 3. The Role of DMP1 in odontogenesis appears to be local and not systemic.

Panel A, representative radiographs demonstrate a similar thin dentin wall (arrowhead) in the molars from VDR KO (middle) and Dmp1 KO mice (right) compared to wild type controls (WT, left). Panel B, the procion red dye, which diffuses through the dentinal tubule system, shows no gross abnormalities in the appearance of dentin tubules in the VDR KO mice (middle). In contrast, dramatic abnormalities in the dentin tubular morphology are observed in the Dmp1 KO mice (right) compared to controls (left). Bar = 10μm Panel C, a high calcium diet, fed to the mice from weaning until 2 months of age, fails to rescue the reduced dentin thickness (arrow) observed in the DMP1-KO mice (right) compared to controls (left).

Taken together, these data suggest that DMP1 plays a critical role in establishing the correct architecture and organization of the dentin tubular system and that the abnormalities in the dentin tubules of Dmp1-null mice are likely not a secondary consequence of impaired mineralization. Therefore DMP1 may have specific roles in both regulations of mineralization and in formation and/or maintenance of the dentin tubular system.

Exclusion of the potential effect of systemic calcium on the Dmp1-null phenotype

Due to the specific localization of DMP1 on the walls of the dentin tubules and our previous observations that Dmp1 is highly expressed in mineralizing cell types (Feng et al., 2003; Feng et al., 2002), we hypothesized that the role of DMP1 in controlling mineralization is mainly local and not systemic. To test this hypothesis, a calcium/phosphorus lactose-enriched diet was fed to Dmp1-null and age-matched littermates immediately after weaning until 2 months of age. Analysis by radiography showed no rescue of the Dmp1-null phenotype by the high calcium diet (Fig 3C), even though this diet has previously been shown to completely rescue the osteomalacia phenotype of VDR KO mice (Amling et al., 1999). These data suggest that the mechanism by which DMP1 regulates mineralization is likely local rather than systemic, and is different from that mediated through vitamin D receptor actions.

Overexpression of Dmp1 Driven by the 3.6 kb Col 1a1 or the Dspp promoter on a wild-type background has no apparent effect on normal tooth development

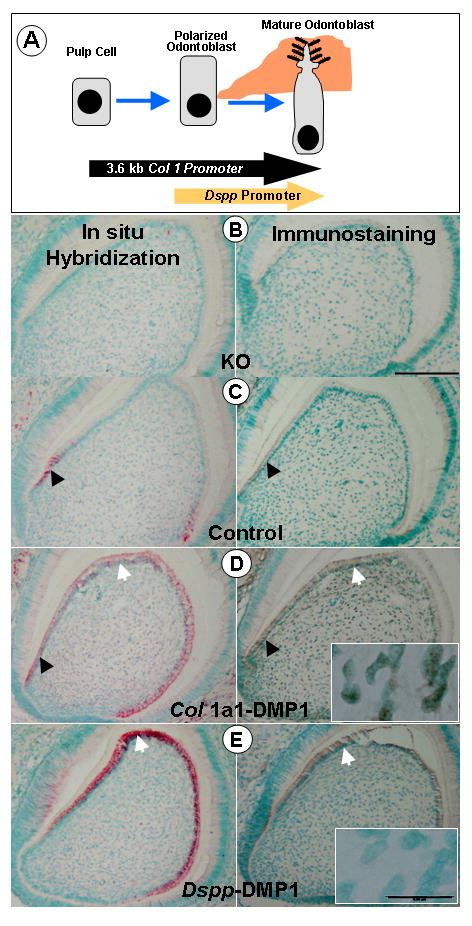

The Dmp1-null mice show profound abnormalities in mineralized tissues postnatally (Ye et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2005). However, it is sometimes difficult to define the mechanisms of action of a gene simply by characterizing the null phenotype as this phenotype could result from the complex interactions of many cellular processes. To achieve a better understanding of protein function, it is often useful to compare both gain of function and loss of function approaches. We therefore next generated transgenic mice which overexpressed Dmp1 either under the control of the 3.6 kb Col 1a1 promoter, which will result in expression of DMP1 in both the pulp and odontoblast cells (Braut et al., 2002; Mina and Braut, 2004) or under control of the Dspp promoter, which targets expression to mature odontoblasts only (Sreenath et al., 1999). We also used the Dmp1-null mice as a genetic background on which to re-express Dmp1 under control of these promoters to define at which stage in odontoblast differentiation the expression of Dmp1 was required. Fig 4A shows a schematic representation of when the Col 1a1 and Dspp promoters are expressed during odontogenesis.

Fig. 4. Rescue strategy and targeted re-expression of transgenic DMP1 in Dmp1 KO Mice.

Panel A, shows a schematic diagram depicting the key steps in odontoblast differentiation. The arrows corresponding to the Col1a1 and Dspp promoters indicate when these promoters are active during the odontogenesis pathway. Transgenic mice were generated in which the coding region of the murine Dmp1 cDNA was expressed under control of the Col1a1 promoter (for early expression in pulp cells and odontoblasts) or under control of the Dspp promoter (for expression in mature odontoblasts). These transgenic mice were crossed onto the Dmp1-null background for re-expression of DMP1 at specific stages during odontogenesis. Panels B–E show in situ hybridization (red staining with green nuclear counterstain) and immunostaining (brown staining with green nuclear counterstain) for DMP1 in the lower 3rd molar in 10 day old mice. In Dmp1-KO mice (B), no DMP1 was detected, either at the mRNA (left) or protein (right) level. In control mice (C), endogenous expression of DMP1 mRNA (left) and protein (right) was observed in the early odontoblasts (black arrows). In Dmp1-KO mice expressing the Col 1a1-DMP1 transgene (D), strong expression of DMP1 RNA and protein was observed in both early (arrowhead) and mature (arrow) odontoblasts. Expression was also seen in the pulp cells (inset). In Dmp1-KO mice expressing the Dspp-DMP1 transgene (E) expression of DMP1 was detected in mature odontoblasts (arrow). Unlike the Col1a1 transgene, there was no expression of the Dspp-DMP1 transgene in the pulp cells (inset). (Bar = 25μm, inset bar = 5μm).

Four independent lines were obtained for the 3.6 kb Col1a1-DMP1 transgenic mice and seven lines for the Dspp-DMP1 transgenic mice. All founders were fertile. Surprisingly, when Dmp1 was overexpressed on a wild type background, either under control of the Col1a1 or Dspp promoters, no apparent phenotype was observed, either by radiographical or histological examination (data not shown). Expression of the Dmp1 transgene at both the mRNA and protein level was confirmed, in the expected locations and showed that expression of the transgene was actually higher than expression of the endogenous Dmp1 gene (data not shown).

Transgenic expression of DMP1 using the 3.6 Col1a1-promoter completely rescues the dentin defects in the Dmp1-null model, while DMP1 expressed by the Dssp promoter only partially rescues the dentin defects

To determine when during odontogenesis the expression of Dmp1 is critical for normal dentin formation, Dmp1 was re-expressed on the Dmp1-null background at specific stages of odontoblast differentiation. Two independent lines, one with high and one with low expression levels, were used from each of the transgenic mice to cross onto the Dmp1-null mice, thereby re-expressing Dmp1 in early or late odontoblasts. Fig 4B shows in situ hybridization (left panel) and immunostaining (right panel) confirming the lack of expression of endogenous Dmp1 in Dmp1-null mice. In Het control mice (Fig 4C), expression of Dmp1 was found predominantly in the early odontoblasts, as we have reported previously (Feng et al., 2003). Fig 4D shows Dmp1-null mice in which Dmp1 has been re-expressed under control of the Col1a1 promoter. By both in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, expression of DMP1 was observed in the pulp cells and odontoblasts, as expected. When DMP1 was re-expressed under control of the Dspp promoter (Fig 4E) expression of the DMP1 transgene was observed only in mature odontoblasts. Interestingly, the expression level of the DMP1 transgene (Col 1-DMP1 or Dspp-DMP1) was equivalent to or much higher than endogenous Dmp1 expression in the Het controls, as determined both at the protein and mRNA levels (Fig 4C–E).

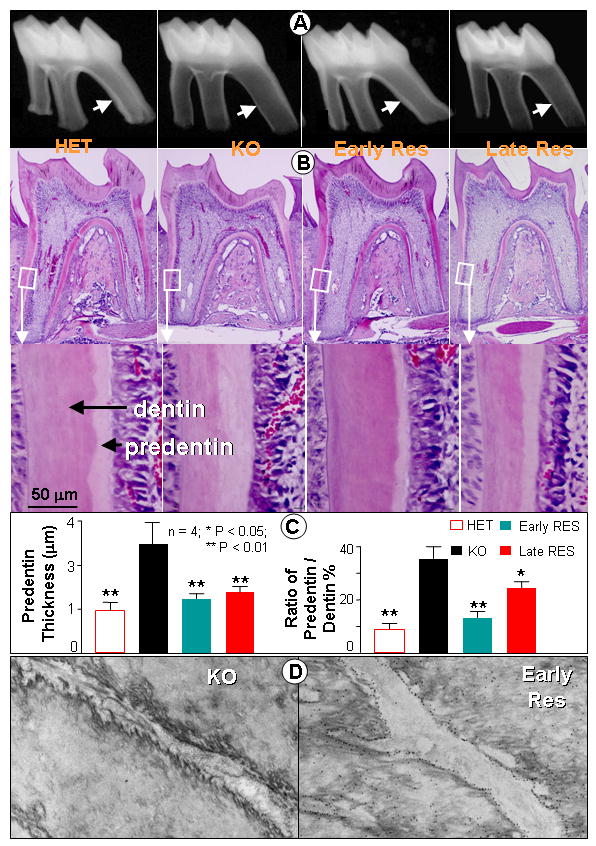

To determine the effect of re-expression of DMP1 at specific stages in odontoblast differentiation, the lower 1st molars from one month old mice were examined by radiography and histology. Representative radiographs show full rescue of dentin thickness by the 3.6 Col 1a1-DMP1 transgene (Early Res) and only a partial rescue by the Dspp-DMP1 transgene (Late Res) (Fig 5A). Histological examination by H&E staining confirmed that there was a complete rescue of abnormalities in both the dentin and predentin when Dmp1 was re-expressed using the Col1a1 (early) promoter. In contrast, only a partial rescue was observed when Dmp1 was re-expressed using the Dspp (late) promoter (Fig 5B). Quantitation of the dentin and predentin thickness by histomorphometry confirmed a more than two fold increase in predentin thickness in Dmp1-null mice. The Col1a1-DMP1 transgene was able to fully rescue the dentin and predentin thickness and restore the predentin to dentin ratio to control levels (Fig 5C). In contrast, the Dspp-DMP1 transgene rescued the predentin thickness but failed to rescue the dentin thickness. Thus the Dspp-DMP1 transgene was only able to partially restore the ratio of predentin to dentin (Fig 5C).

Fig. 5. Full or partial rescue of the tooth phenotype in Dmp1-KO mice by re-expression of transgenic DMP1 under control of the 3.6 kb Col1a1 (Early Rescue) or Dspp (Late Rescue) promoters.

Panel A shows radiographs of the lower first molar from one month old control (HET) and Dmp1 KO (KO) mice as well as KO mice re-expressing DMP1 under control of the Col1a1 promoter (early rescue) and Dspp promoter (late rescue). Note the reduced thickness of the dentin wall (arrow) in the KO mice that is rescued by the Col1a1-DMP1 (early) transgene but not by the Dspp-DMP1 (late) transgene. Panel B shows H & E staining of the first molars from the HET control (left), Dmp1 KO (left center), early rescue (right center), and late rescue mice (right). Enlarged images of the dentin and predentin are shown below. Bar = 50μm. Panel C shows quantitative analysis of the dentin thickness and dentin/predentin ratio. Note that the Col 1a1-DMP1 transgene completely rescues the dentin phenotype in these mice, whereas the Dspp-DMP1 transgene only restores the predentin thickness (data are mean ±SEM from n=4 replicates, significance was determined by ANOVA, followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons, *= p<0.05, **=p<0.01). Panel D shows TEM images of dentinal tubules after immunogold staining for DMP1 using 14 nm gold labeled antibodies. Note the absence of labeling in the Dmp1-null mice (left), together with the irregular surface of the tubule wall. Re-expression of DMP1 under control of the Col1a1 promoter (Early RES) is shown on the right. Note the accumulation of gold labeling on the tubular wall, which also has a smooth morphology.

By immunogold TEM, we observed that a lack of DMP1 was linked to abnormalities in the dentinal tubule walls, which appeared to have much rougher and more irregular surfaces (Fig 5D, left panel). Restoration of DMP1 expression using the Col1a1-DMP1 transgene restored the normal distribution of DMP1 within the dentin tubule walls and rescued these irregularities in morphology (Fig 5D, right panel). These data suggest that this transgene was able to rescue both abnormalities in dentin tubule formation as well as the defect in mineralization in Dmp1-null mice.

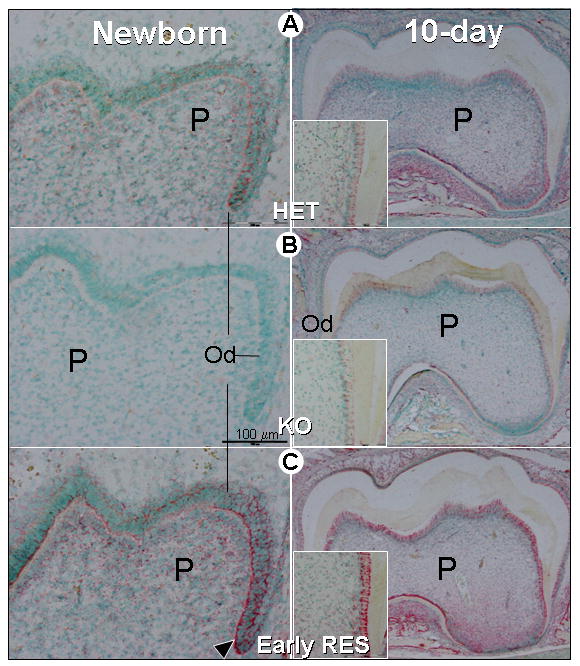

Expression of DMP1 under control of the 3.6 kb Col 1a1 promoter restores osterix expression level

Overexpression of DMP1 in vitro induces differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells and enhances mineralization (Narayanan et al., 2001b), suggesting that one of the mechanisms by which DMP1 regulates dentin mineralization may be via control of odontoblast differentiation in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we examined expression of osterix, a transcriptional factor that is essential for early osteoblast differentiation (de Crombrugghe B, 2001) and has been linked to tooth formation (Mary MacDougall, personal communication). In newborn Het control mice, osterix was expressed in both pulp and odontoblast cells as determined by in situ hybridization (Fig 6A, left panel). In contrast, in Dmp1-null newborns, expression of osterix was very low (Fig 6A, right panel) and its expression remained at a low level in 10 day old animals compared to controls (Fig 6B). Transgenic re-expression of DMP1 driven by the 3.6 Col1a1 promoter completely rescued osterix expression in both pulp and odontoblast cells and in fact induced expression of levels of osterix that were higher than in control mice (Fig 6C). These data show that a lack of Dmp1 expression results in downregulation of a transcription factor known to be important in osteoblast and odontoblast differentiation. These observations are in agreement with our previous report that DSPP (an odontoblast marker) is reduced in Dmp1-null mice (Ye et al., 2004), therefore supporting a role for DMP1 in odontoblast differentiation.

Fig. 6. Reduced osterix expression in the tooth in Dmp1-KO mice and its restoration by re-expression of DMP1 under control of the Col1a1 promoter.

Panel A. In situ hybridization in the lower first molar of newborn (left) and 10-day-old-mice shows that in control (HET) mice, the transcription factor, osterix, is expressed in both pulp cells (P) and odontoblasts (Od) (red staining indicates RNA expression and nuclei are counterstained in green). Panel B. At this time, in the Dmp1 KO mice (KO) osterix was undetectable in the newborn molar (left) with a low level in 10-day-old molar (right). Panel C. Re-expression of DMP1 under control of the Col 1a1 promoter in mice lacking endogenous DMP1 (Early RES) restored osterix expression in both pulp and odontoblast cells from newborns (left) and 10-day-old molars (right). The insert showed an enlargement of the 10-day-old root dentin area. The expression level in the rescued mice was actually higher than in control animals. Bar = 100μm.

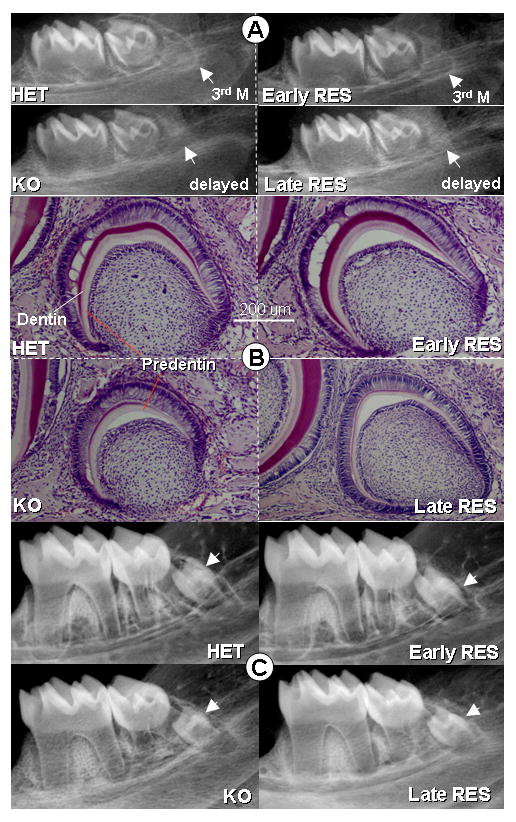

The Col 1a1-DMP1, but not Dspp-DMP1 transgene, restores the delayed 3rd molar development seen in the Dmp1-null mice

We have previously shown that there is delayed development of the third molar in the Dmp1-null mice (Ye et al., 2004). We therefore examined whether re-expression of DMP1 in early or late odontoblasts could rescue the development of the third molar. Fig 7A shows radiographs from ten day old heterozygous control mice compared to Dmp1-null mice and Dmp1-null mice in which Dmp1 was re-expressed under control of the Col1a1 (early) or Dspp (late) promoters. In the KO mice, delayed development of the third molar was observed, which was rescued by the Col1a1-DMP1 transgene but not the Dspp-DMP1 transgene. These data suggest that early expression of DMP1 is required for normal development of the third molars.

Fig. 7. Rescue of delayed development of the third molars in Dmp1-KO mice by re-expression of DMP1 under control of the 3.6 kb Col1a1 but not the Dspp promoter.

Panel A shows radiographs of the mandible of ten day old mice. Note that in the control mice (HET), the third molar is evident on the radiograph. However, in Dmp1-KO mice (KO), the development of the third molar is delayed. Re-expression of DMP1 under control of the Col1a1 transgene (Early RES) rescues the development of the third molar but the Dspp-DMP1 transgene fails to rescue third molar development. Panel B shows H&E staining of sections through the mandible, confirming the delayed development of the third molar in Dmp1-KO mice and its rescue by the Col1a1-DMP1 transgene (Early RES) but not the Dspp-DMP1 transgene (Late RES) (Bar = 200μm). Panel C shows radiographs of the mandible from one month old mice. Note that in these one month old animals, the third molar appears similar in control, Dmp1-KO and the early and late rescued animals suggesting that in Dmp1-KO mice there is only a delay, but not a failure in development of the third molar.

Histological analysis confirmed the delayed development of the third molar in Dmp1-null mice (Fig 7B) and confirmed that this was rescued by the Col1a1-DMP1 but not the Dspp-DMP1 transgene. Interestingly, by one month of age the size of the 3rd molar in Dmp1-null and the KO mice expressing the Dspp-DMP1 transgene appeared similar to controls (Fig 7C), suggesting that there is only a delay in third molar formation rather than a failure in formation.

DISCUSSION

In this study the Dmp1 deletion, overexpression and re-expression data provide important new insights into the function of this molecule. These data suggest that DMP1 has important roles during odontogenesis at least two different levels, including (i) formation and/or maintenance of the dentin tubular system, (ii) and mineralization of the dentin. DMP1 also plays a unique role in development of the third molar that appears to be distinct from its functions in the other teeth. Furthermore, the role of DMP1 in mineralization appears to be locally mediated, as it was not rescued by a high calcium and phosphate diet, suggesting that the pathways are distinct from other models of dentin hypomineralization, such as the VDR knockout mice.

By re-expressing DMP1 in Dmp1-null mice at different stages of odontoblast differentiation, we have shown that DMP1 plays critical roles in the early odontoblast and that in order to fully rescue the mineralization defect in the Dmp1-null mice, expression is required in both early and late odontoblasts. Thus, the end point of normal dentin mineralization, probably results from the combined effects of DMP1 on odontoblast differentiation, dentin tubule formation as well as its local effects on mineralization.

Interestingly, neither heterozygous Dmp1-null mice nor Dmp1 overexpressing mice showed an apparent phenotype. These observations suggest that there may be a threshold level of DMP1 required for normal odontogenesis, but above that level, the actual amount of DMP1 does not have a dose-related effect. As DMP1 purified from rat bone is in the form of cleaved N-terminal and C-terminal fragments (Qin et al., 2003), a possible explanation is that the intact DMP1 itself may not be biologically active and that proteolytic cleavage into active forms may be required for DMP1 to exert biological effects. Thus, excess DMP1 would have no biological effect unless sufficient protease was present in the appropriate cells for cleavage into its active forms. Such a mechanism would explain why an excess amount of DMP1 produces no apparent phenotype but re-expression of DMP1 on a Dmp1-null background rescues the phenotype. In fact, for each of the DMP1 overexpressing lines (Col 1-DMP1 and Dspp-DMP1), we used two independent transgenic mouse lines, one with high and one with low expression levels for crossing onto the Dmp1-null mice. In both cases, we did not see apparent dosage effects of the expression levels of the transgene on rescue efficiency, suggesting that the expression time and/or location is critical as shown in Figs 4–7.

In further, overexpression of DMP1 had no apparent effect on dentin apposition rate but rescues the defect of dentin apposition rate when crossed to Dmp1-null mice (Supplementary Fig 1). Again, this information is consistent with the data discussed above.

An intriguing question in the function of DMP1 is its role in formation and/or maintenance of the dentin tubular system and whether this may be linked to its role in regulating mineralization. Our data suggest that, unlike other models of dentin hypomineralization, such as the VDR knockout mice, DMP1 appears to exert its control over mineralization via a local mechanism. We propose that an intact, open dentin tubular system may be required during mineralization for delivery of calcium/phosphorus to sites of mineralization. Through its role in formation and/or maintenance of the dentin tubules, DMP1 may be therefore providing an essential conduit for calcium and phosphate to facilitate the mineralization process. As deletion of DMP1 results in malformation of the dentinal tubular network, this may result in a failure to deliver calcium/phosphorus to sites of mineralization, thus contributing to the hypomineralized phenotype.

A study by George and co-workers (Narayanan et al., 2003) has provided evidence that DMP1 itself may function as a transcription factor. Such an activity may contribute to the apparent effects of DMP1 on odontoblast differentiation in vivo. Our data showing reduced expression of DSPP (an odontoblast marker)(Ye et al., 2004) and osterix (a transcription factor important in odontogenesis, Fig 6) supports a role for DMP1 in odontoblast differentiation. Second, transient transfection of CMV-DMP1 (Supplementary Fig 2A) led to an increase of alkaline phosphatase activity in C3H10T1/2 (a mouse pluripotent cell line, 5.4-fold), 17IA4 (Pre-odontoblast cell line, 4.8-fold) or 17IIA11 (odontoblast cell line, 3.3 fold). Third, overexpression of DMP1 resulted in a 3-fold increase of DSPP mRNA and a 2-fold increase of osterix mRNA in vitro (Supplementary Fig 2B). These in vitro observations further support roles of DMP1 in regulation of odontoblast differentiation. However, this does not imply that differentiation is completely arrested in the Dmp1-null mice. Instead, the differentiation is likely delayed, which would be consistent with formation of lower amounts of dentin and predentin (Fig 5).

In summary, these studies have identified DMP1 as a key regulator of odontoblast differentiation, formation of the dentin tubular system and as a regulator of dentin mineralization. Targeted re-expression of DMP1 in Dmp1-null mice has shown that DMP1 expression is required in early odontoblasts, but that its continued expression in mature odontoblasts is also required for normal dentinogenesis. These observations highlight DMP1 as a candidate gene for human disorders of dentin mineralization and potentially for conditions of tooth agenesis. The future study of this key molecule may also provide important new insights into how the process of mineralization in dentin is locally regulated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mark Dallas for assistance in quantitation of dentin thickness, Drs. Vladmir Dusevich and Neelambar Kaipator for assistance with electron microscopy, and Dr. Anne Poliard for providing odontoblast cell lines. We also thank Drs. Lynda Bonewald and Stephen E. Harris for critical reading of the manuscript. Support for this research was provided by grants AR046798 and AR51587 (to J.Q.F) from the National Institutes of Health, and MT11360 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Ling Ye was supported by T32DE07294 (to D. E) and DE016977 from the NIH/NIDCR.

References

- Amling M, Priemel M, Holzmann T, Chapin K, Rueger JM, Baron R, Demay MB. Rescue of the skeletal phenotype of vitamin D receptor-ablated mice in the setting of normal mineral ion homeostasis: formal histomorphometric and biomechanical analyses. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4982–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braut A, Kalajzic I, Kalajzic Z, Rowe DW, Kollar EJ, Mina M. Col1a1-GFP transgene expression in developing incisors. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:216–9. doi: 10.1080/03008200290001078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler WT, Brunn JC, Qin C, McKee MD. Extracellular matrix proteins and the dynamics of dentin formation. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:301–7. doi: 10.1080/03008200290000682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Shapiro HS, Sodek J. Development expression of bone sialoprotein mRNA in rat mineralized connective tissues. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:987–97. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza RN, Cavender A, Sunavala G, Alvarez J, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB, MacDougall M. Gene expression patterns of murine dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) and dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) suggest distinct developmental functions in vivo. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 1997;12:2040–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.12.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Crombrugghe BLV, Nakashima K. Regulatory mechanisms in the pathways of cartilage and bone formation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2001;13:721–727. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt DT, Noda M. Osteopontin expression and function: role in bone remodeling. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1998;30–31:92–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JQ, Huang H, Lu Y, Ye L, Xie Y, Tsutsui TW, Kunieda T, Castranio T, Scott G, Bonewald LB, Mishina Y. The Dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) is specifically expressed in mineralized, but not soft, tissues during development. J Dent Res. 2003;82:776–80. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JQ, Luan X, Wallace J, Jing D, Ohshima T, Kulkarni AB, D’Souza RN, Kozak CA, MacDougall M. Genomic organization, chromosomal mapping, and promoter analysis of the mouse dentin sialophosphoprotein (Dspp) gene, which codes for both dentin sialoprotein and dentin phosphoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9457–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng JQ, Zhang J, Dallas SL, Lu Y, Chen S, Tan X, Owen M, Harris SE, MacDougall M. Dentin matrix protein 1, a target molecule for Cbfa1 in bone, is a unique bone marker gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1822–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LW, Whitson SW, Avioli LV, Termine JD. Matrix sialoprotein of developing bone. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12723–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa R, Butler WT, Brunn JC, Zhou HY, Kuboki Y. Differences in composition of cell-attachment sialoproteins between dentin and bone. J Dent Res. 1993;72:1222–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720081001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Gui J, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Veis A. In situ localization and chromosomal mapping of the AG1 (Dmp1) gene. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 1994;42:1527–31. doi: 10.1177/42.12.7983353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Sabsay B, Simonian PA, Veis A. Characterization of a novel dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein. Implications for induction of biomineralization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:12624–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A, Silberstein R, Veis A. In situ hybridization shows Dmp1 (AG1) to be a developmentally regulated dentin-specific protein produced by mature odontoblasts. Connective Tissue Research. 1995;33:67–72. doi: 10.3109/03008209509016984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher MJ. Mechanism of calcification: role of collagen fibrils and collagen-phosphoprotein complexes in vitro and in vivo. Anatomical Record. 1989;224:139–53. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092240205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JP. Is all bone the same? Distinctive distributions and properties of non-collagenous matrix proteins in lamellar vs. woven bone imply the existence of different underlying osteogenic mechanisms. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine. 1998;9:201–23. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst KL, Ibaraki-O’Connor K, Young MF, Dixon MJ. Cloning and expression analysis of the bovine dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein gene. Journal of Dental Research. 1997;76:754–60. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter GK, Hauschka PV, Poole AR, Rosenberg LC, Goldberg HA. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochemical Journal. 1996;317:59–64. doi: 10.1042/bj3170059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knothe Tate ML, Adamson JR, Tami AE, Bauer TW. The osteocyte. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Amling M, Pirro AE, Priemel M, Meuse J, Baron R, Delling G, Demay MB. Normalization of mineral ion homeostasis by dietary means prevents hyperparathyroidism, rickets, and osteomalacia, but not alopecia in vitamin D receptor-ablated mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4391–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, Demay MB. Targeted ablation of the vitamin D receptor: an animal model of vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9831–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y, Rios HF, Myers ER, Lu Y, Feng JQ, Boskey AL. DMP1 depletion decreases bone mineralization in vivo: an FTIR imaging analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2169–77. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C, Yoneda T, Boyce BF, Chen H, Mundy GR, Soriano P. Osteopetrosis in Src-deficient mice is due to an autonomous defect of osteoclasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4485–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, DuPont BR, Simmons D, Leach RJ. Assignment of DMP1 to human chromosome 4 band q21 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenetics & Cell Genetics. 1996;74:189. doi: 10.1159/000134410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, Gu TT, Luan X, Simmons D, Chen J. Identification of a novel isoform of mouse dentin matrix protein 1: spatial expression in mineralized tissues. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 1998;13:422–31. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall M, Simmons D, Luan X, Gu TT, DuPont BR. Assignment of dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) to the critical DGI2 locus on human chromosome 4 band q21.3 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;79:121–2. doi: 10.1159/000134697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DM, Hallsworth AS, Buckley T. A method for the study of internal spaces in hard tissue matrices by SEM, with special reference to dentine. J Microsc. 1978;112:345–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1978.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee MD, Nanci A. Postembedding colloidal-gold immunocytochemistry of noncollagenous extracellular matrix proteins in mineralized tissues. Microsc Res Tech. 1995;31:44–62. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070310105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC, Omura TH, Smith LJ. Changes in dentin appositional rates during pregnancy and lactation in rats. J Dent Res. 1985;64:1062–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345850640080701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina M, Braut A. New insight into progenitor/stem cells in dental pulp using Col1a1-GFP transgenes. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:120–33. doi: 10.1159/000075033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K, Ramachandran A, Hao J, He G, Park KW, Cho M, George A. Dual functional roles of dentin matrix protein 1. Implications in biomineralization and gene transcription by activation of intracellular Ca2+ store. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17500–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K, Srinivas R, Ramachandran A, Hao J, Quinn B, George A. Differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells by overexpression of dentin matrix protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001a;98:4516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K, Srinivas R, Ramachandran A, Hao J, Quinn B, George A. Differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells by overexpression of dentin matrix protein 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001b;98:4516–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081075198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagerakis P, Berdal A, Mesbah M, Peuchmaur M, Malaval L, Nydegger J, Simmer J, Macdougall M. Investigation of osteocalcin, osteonectin, and dentin sialophosphoprotein in developing human teeth. Bone. 2002;30:377–85. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Brunn JC, Cook RG, Orkiszewski RS, Malone JP, Veis A, Butler WT. Evidence for the proteolytic processing of dentin matrix protein 1. Identification and characterization of processed fragments and cleavage sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34700–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Brunn JC, Jones J, George A, Ramachandran A, Gorski JP, Butler WT. A comparative study of sialic acid-rich proteins in rat bone and dentin. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:133–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert T, Storkel S, Becker K, Fisher LW. The role of osteonectin in human tooth development: an immunohistological study. Calcif Tissue Int. 1992;50:468–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00296779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Iwase M, Maslan S, Nozaki N, Yamauchi M, Handa K, Takahashi O, Sato S, Kawase T, Teranaka T, Narayanan AS. Expression of cementum-derived attachment protein in bovine tooth germ during cementogenesis. Bone. 2001;29:242–8. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro HS, Chen J, Wrana JL, Zhang Q, Blum M, Sodek J. Characterization of porcine bone sialoprotein: primary structure and cellular expression. Matrix. 1993;13:431–40. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenath TL, Cho A, MacDougall M, Kulkarni AB. Spatial and temporal activity of the dentin sialophosphoprotein gene promoter: differential regulation in odontoblasts and ameloblasts. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 1999;43:509–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaix PH, Doulaverakis M, George A, Fisher LW, Butler WT, Qin C, Salih E, Tan M, Fujimoto Y, Spevak L, Boskey AL. In vitro effects of dentin matrix protein-1 on hydroxyapatite formation provide insights into in vivo functions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18115–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, Li Z, Lu Y, Mishina Y, Feng JQ. Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19141–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Mishina Y, Chen D, Huang H, Dallas SL, Dallas MR, Sivakumar P, Kunieda T, Tsutsui TW, Boskey A, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ. Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6197–203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412911200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitake H, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Noda M. Osteopontin-deficient mice are resistant to ovariectomy-induced bone resorption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8156–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Xie Y, Li G, Kong J, Feng JQ, Li YC. Critical role of calbindin-D28k in calcium homeostasis revealed by mice lacking both vitamin D receptor and calbindin-D28k. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52406–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.