Abstract

Myelin is a multispiraled extension of glial membrane that surrounds axons. How glia extend a surface many-fold larger than their body is poorly understood. Schwann cells are peripheral glia and insert radial cytoplasmic extensions into bundles of axons to sort, ensheath, and myelinate them. Laminins and β1 integrins are required for axonal sorting, but the downstream signals are largely unknown. We show that Schwann cells devoid of β1 integrin migrate to and elongate on axons but cannot extend radial lamellae of cytoplasm, similar to cells with low Rac1 activation. Accordingly, active Rac1 is decreased in β1 integrin–null nerves, inhibiting Rac1 activity decreases radial lamellae in Schwann cells, and ablating Rac1 in Schwann cells of transgenic mice delays axonal sorting and impairs myelination. Finally, expressing active Rac1 in β1 integrin–null nerves improves sorting. Thus, increased activation of Rac1 by β1 integrins allows Schwann cells to switch from migration/elongation to the extension of radial membranes required for axonal sorting and myelination.

Introduction

Myelin optimizes conduction of nerve impulses and is formed by multiple membrane wraps of glial cells (for review see Sherman and Brophy, 2005). In the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells (SCs) are the glial cells that associate with axons to form myelinated and nonmyelinated fibers. SCs originate from neural crest and migrate longitudinally along bundles of growing axons. Then, SCs send processes radially within bundles, to segregate out axons destined to be myelinated (axonal sorting), obtain a one-to-one relationship with them, and wrap them with sheets of inwardly spiraling membrane (for review see Jessen and Mirsky, 2005). Axonal sorting is regulated by signals from axons and from the extracellular matrix. Mice lacking laminins have a block in axonal sorting, resulting in bundles of “naked” axons (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973; Stirling, 1975). SCs express laminin receptors, including α6β1, α6β4 integrin, and dystroglycan (for review see Feltri and Wrabetz, 2005). Among these, β1 integrins play a pivotal role in radial sorting, as its absence in SCs causes a defect similar to that of laminin mutants (Feltri et al., 2002). The signaling cascades activated by β1 integrins to promote sorting are poorly known.

Small Rho GTPases, such as Rac, Cdc42, and RhoA, are signaling molecules that cycle between an active (GTP bound) and an inactive (GDP bound) state. They influence cell shape by regulating actin upon activation from various stimuli, including integrin engagement (Hall et al., 1993; Nobes and Hall, 1995; Del Pozo et al., 2002, 2004). Rac1 promotes actin polymerization to produce lamellipodia and ruffles. Low levels of active Rac1 produce axial (at the two extremities of the main cell axis) lamellae, favoring directional cell migration, whereas higher levels of Rac1 produce radial (around the whole cell perimeter) lamellae (Pankov et al., 2005). Cdc42 regulates the formation of filopodia, whereas RhoA leads to the assembly of stress fibers and of focal adhesions (Nobes and Hall, 1995). Small GTPases are active in the peripheral nervous system (Terashima et al., 2001). Studies in Drosophila and in vitro proposed a role for Rac1 in glial migration and oligodendrocyte differentiation and for RhoA in internodal and nodal organization (Sepp and Auld, 2003; Liang et al., 2004; Melendez-Vasquez et al., 2004; Yamauchi et al., 2005). Little is known on the role of small GTPases in mammalian peripheral nerves and during sorting and myelination.

Here, we first determine that β1 integrin–null SCs display normal cytoskeletal dynamics during migration and elongation on axons, but cannot produce radial lamellipodia, similar to cells with reduced levels of active Rac1. Second, we show that the levels of active Rac1 are reduced in nerves lacking β1 integrin in SCs and that Rac1 is not targeted to the membrane of β1 integrin–null SCs. Third, we generate a mouse with specific Rac1 deletion in SCs and show that Rac1 regulates radial lamellipodia, segregation of axons, and myelination. Finally, we show that exogenous activation of Rac1 in β1 integrin–null nerves ameliorates the sorting defects. We conclude that SCs longitudinally oriented and elongated on axons produce radial processes that segregate and then myelinate axons upon β1 integrin–mediated activation of Rac1.

Results

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) explants from β1 integrin conditional null mice show impaired myelination

Perturbation of β1 integrin in SCs impairs interactions with axons during radial sorting and precludes myelination (Fernandez-Valle et al., 1994; Feltri et al., 2002). To test whether this is due to the inability of β1 integrin–null SCs to reorganize the cytoskeleton during axonal interactions, we used organotypic cultures of DRG from wild-type (wt) or β1 integrin/P0-Cre–conditional null mice. These mice lose β1 integrin expression in SCs after embryonic day (E) 17.5 (Feltri et al., 2002).

We first characterized mutant DRG cultures explanted at E14.5. Mutant DRG reached a maximum of 60% β1-negative SCs after 4 wk in culture (Fig. 1 A′), in contrast to postnatal nerves, where the extent of P0-Cre–mediated recombination was nearly complete (Feltri et al., 2002). β1-null SCs migrated at distances from DRG (Fig. 1 A″). The number of SC nuclei was not reduced in mutant cultures (Fig. 1 E), although mutant SCs have a slight increase in the fraction of apoptotic nuclei (not depicted). Because of the presence of both β1-negative and -positive SCs, the absence of β1 integrin was always confirmed by direct or retrospective staining (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200610014/DC1).

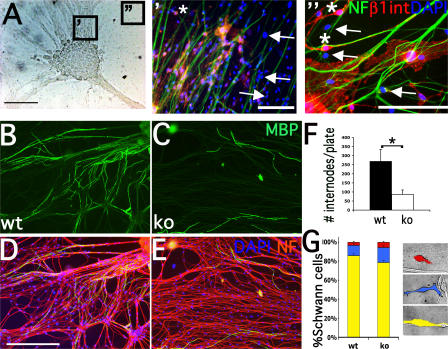

Figure 1.

DRG cultures from β1 integrin–null mice manifest impaired myelination. (A, A′, and A″) DRG cultures from mice with SC deletion of β1 integrin (phase in A) contain a mixture of β1 integrin–positive (asterisks) and –negative (arrows) SCs. Cells were stained with anti–β1 integrin (red) and anti-neurofilament (NF; green) antibodies, and with DAPI (blue) to visualize nuclei. β1 integrin–null SCs are found at distance from the neuronal cell bodies (A″). (B and C) Staining with anti-MBP antibodies reveals that SCs in mutant cultures synthesize fewer myelin internodes (F; P < 0.05 by t test, three plates per genotype for each experiment, n = 4). (D and E) Staining with anti-neurofilament antibodies (red) and DAPI (blue) shows that the numbers of axons and SC nuclei (small, cigar-shaped, and associated with axons) are not reduced in mutant cultures. (G) β1 integrin–positive and –negative cells (recognized using anti–β1 integrin antibodies; not depicted) were classified based on their relationship with axons. The number of β1 integrin–null SCs associated with axons was slightly reduced (mutant versus wt: P < 0.05 for red group, P < 0.01 for blue group, and P < 0.001 for yellow group by t test; n = 3,902 wt and 5,536 knockout [ko]). Red indicates not contacting, blue indicates not longitudinally oriented, and yellow indicates properly associated. Error bars indicate SEM. Bars: (A) 200 μm; (A′ and B–E) 100 μm; (A″) 50 μm.

To validate β1 integrin–null cultures, we asked if they could myelinate after ascorbic acid supplement. The number of myelin internodes stained with anti–myelin basic protein (MBP) antibody was significantly lower in mutant cultures (P < 0.05; Fig. 1, C and F). Defective myelin formation was not due to a reduced number of SCs or axons, as demonstrated by DAPI (cigar-shaped SC nuclei) and neurofilament staining (Fig. 1, D and E). Thus, cultures from β1 integrin–null mice showed defective myelination and could be used as a model to analyze the cytoskeleton of mutant SCs as they interact with axons.

β1 integrin–null SCs maintain proper association with axons

The inability of β1 integrin–null SCs to sort axons could be due to impaired longitudinal migration on axons; lack of recognition, orientation, or association with axons; or inability to send processes toward or radially between axons. To distinguish between these possibilities, we visualized static and dynamic SC–axon interactions by videomicroscopy.

To evaluate whether mutant SCs maintained proper orientation and association with axons, we analyzed these parameters at 3–5 wk in culture. Cells were classified based on their relationship with axons (Fig. 1 G), and their proportions were quantified. β1 integrin–null SCs presented a slight decrease in the percentage of cells associated with axons (Fig. 1 G). Despite the statistically significant difference, this decrease is probably not sufficient to explain the dramatic impairment of mutant SCs to form myelin.

β1 integrin–null SCs recognize and explore axons normally using growth cone–like processes and migrate on axons

To evaluate the dynamic interactions between mutant SCs and axons, we used time-lapse microscopy. Previous experiments showed that SC tips remodel resembling growth cones, with filopodia and lamellipodia (Gatto et al., 2003). We asked whether mutant SCs manifest this behavior near axons in the presence or absence of ascorbic acid. In both conditions, mutant and wt SCs behaved similarly, as they organized dynamic processes at one extremity that interacted with and moved around the axon (Fig. S2 and Videos 3 and 4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200610014/DC1). The time frame during which these growth cone–like processes were dynamically reorganized was similar in both genotypes (Fig. S2 and Videos 1–4).

Next, we analyzed the ability of mutant SCs to migrate along axons in the presence or absence of ascorbic acid. No qualitative differences were observed between the migration of wt and mutant SCs. Both the cells sent filopodia-like processes to “sample” the environment, extended an axial lamellipodium, translocated the nucleus, and retracted the uropod. The time, extent of migration, and uropod retraction was similar (Fig. S2 and Videos 1 and 2). This suggests that β1 integrin does not determine the ability of SCs to move longitudinally along axons.

In conclusion, mutant SCs perform correct “early” axonal interactions, namely, orientation, longitudinal migration, and association. After these steps, SCs must sort and myelinate axons by inserting processes radially within bundles and then around single axons. We modeled this phenomenon using isolated SCs spreading on a substrate.

β1 integrin–null SCs have a defect in radial lamellipodia

To visualize the ability of mutant SCs to extend radial processes, we asked if they were able to spread on laminin, vitronectin, or poly-l-lysine (PLL). β1 integrin–null SCs spread less when plated on laminin (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, the spreading of mutant and wt cells plated on vitronectin and PLL was similar. This is consistent with the fact that β1 integrin is contained in all laminin receptors expressed by cultured SCs except dystroglycan (Einheber et al., 1993; Feltri et al., 1994; Tsiper and Yurchenco, 2002; Saito et al., 2003), whereas β1 integrin–null and wt SCs express the vitronectin receptor αvβ3 (unpublished data) and PLL promotes non–receptor-specific cell adhesion. Thus, deficient spreading by β1-null SCs results from loss of β1 integrin binding to laminin.

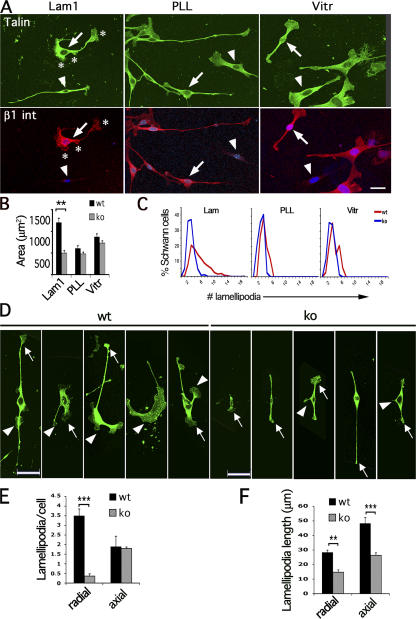

Figure 2.

Reduced number of peripheral lamellipodia in β1 integrin–null SCs. (A) Staining with anti-talin (green) and anti–β1 integrin (red) antibodies reveals that β1 integrin–null SCs (arrowheads) have a smaller surface than wt cells (arrows) when spreading on laminin (Lam1), but not PLL or vitronectin (Vitr). (B) The surface of wt and β1 integrin–null SCs was measured on various substrates. Wt versus β1-null surface, by t test: P < 0.0001 on laminin, n = 86 wt, 40 knockout (ko); P = 0.64 on vitronectin, n = 85 wt, 69 knockout; P = 0.027 on PLL, n = 39 wt, 37 knockout. (C) The number of lamellipodia (asterisks in A) is reduced in mutant SCs plated on laminin, but not PLL or vitronectin (n = 674 wt, 278 knockout on laminin; n = 34 wt, 73 knockout on vitronectin; n = 26 wt, 39 knockout on PLL). (D–F) “Axial” lamellipodia are present at the end of the long axis of the cell, within of a 20° angle (arrows), whereas “peripheral/radial” lamellae are outside this zone (arrowheads). When spreading on laminin, β1 integrin–null SCs have a selective loss of peripheral lamellae. The number of axial lamellae was similar between wt and mutant SCs (1.9 ± 0.54 and 1.8 ± 0.07, respectively; P = 0.325 by t test), whereas the number of peripheral lamellae was significantly reduced in mutant SCs (3.5 ± 0.35 and 0.4 ± 0.11; P < 0.0001 by t test, n = 91 wt and 53 knockout). The length of extension of both axial and peripheral lamellipodia was reduced in β1 integrin–null SCs plated on laminin. Error bars indicate SEM. Bars, 40 μm.

Next, we counted the number of lamellipodia (Fig. 2 A, asterisks). The number of lamellipodia was reduced in β1 integrin–null SCs plated on laminin, but not PLL or vitronectin (Fig. 2, A and C). It was proposed that directed migration and elongation in other cell types depend on the ability to produce axial lamellipodia (Pankov et al., 2005). Axial lamellae are present within of a 20° angle of the extremities of the cell-long axis (Fig. 2 D, arrows), whereas peripheral or radial lamellae are outside this zone (Fig. 2 D, arrowheads; Pankov et al., 2005). Notably, although the number of axial lamellae was similar between wt and mutant SCs plated on laminin, the number of peripheral/radial lamellae was significantly reduced (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2, D and E). The length of extension of both axial and radial lamellipodia was reduced in mutant SCs (Fig. 2 F). Both talin and phalloidin (not depicted) were used to quantify lamellipodia. The relative sparing of axial lamellipodia can explain why mutant SCs migrate and elongate normally on axons (as this process uses axial extension at the edge of the cell-long axis; Pankov et al., 2005) and suggests that mutant SCs are instead unable to insert radial processes within axons.

Rac1 activity controls radial lamellipodia in SCs

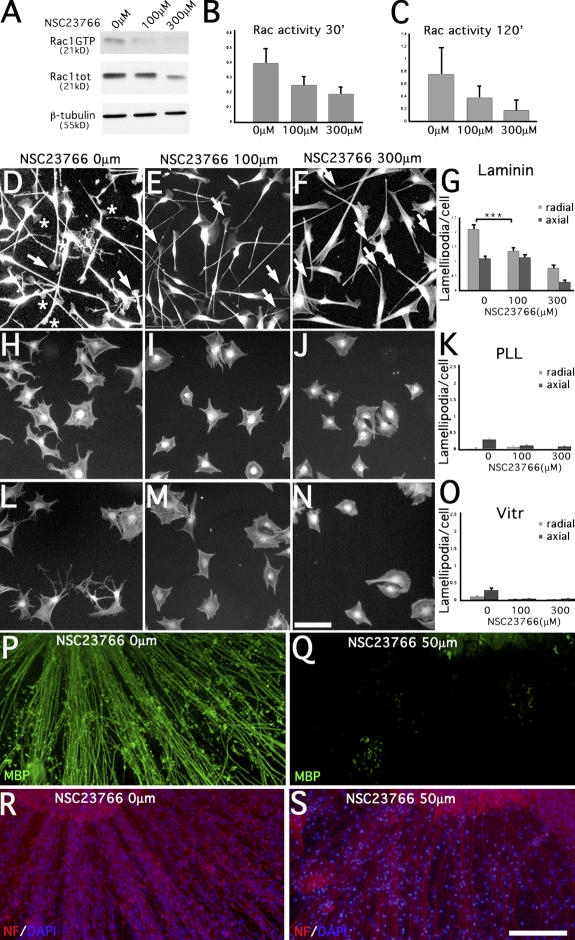

It was recently shown that the formation of radial/peripheral versus axial lamellae in other cell types depends on levels of activation of the small GTPase Rac1 (Pankov et al., 2005). To ask directly if the levels of Rac1 affect the formation of radial and peripheral lamellae in SCs, we inhibited Rac1 using the specific NSC23766 inhibitor (Gao et al., 2004). NSC23766 inhibited the levels of active Rac in rat SCs in a dose-dependent way (Fig. 3, A–C). In the absence of inhibitor, SCs spreading on laminins had both radial and axial lamellipodia (Fig. 3 D). At 100 μM of inhibitor (intermediate levels of active Rac1), the number of radial lamellipodia was reduced (P < 0.0001; n = 100), whereas the number of axial lamellipodia was unchanged (P = 0.6; n = 100; Fig. 3, E and G). Decreasing further the activity of Rac1 reduced the number of both radial and axial lamellipodia (Fig. 3, F and G). Few axial, and nearly no radial, lamellipodia were produced on vitronectin or PLL. Thus, laminins and high levels of Rac1 are required for the formation of radial lamellipodia in SCs. Having shown the effect of NSC23766 on SC lamellipodia, we asked if Rac1 inhibition also affected myelination by SCs in DRG explants. Low doses of inhibitor were sufficient to almost completely inhibit myelination, as shown by the absence of MBP-positive internodes (Fig. 3 Q), without affecting axons and SC number (Fig. 3 S).

Figure 3.

Radial lamellipodia in spreading SCs and myelination are dependent on high levels of active Rac1. Rat SCs spreading on laminin, PLL, or vitronectin were treated with different concentrations of the specific Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766. (A–C) Levels of GTP-bound Rac measured after Western blotting of PDB-GST pull downs using anti-Rac1 antibodies. Active Rac levels were decreased in a dose-dependent fashion after 30 (A and B; mean of three experiments) and 120 min of treatment (C; three experiments). (D–F, H–J, and L–N) Staining of cells using phalloidin after 30 (not depicted) or 120 min of treatment with 0 μm NSC23766 (D, H, and L; arrows indicate axial lamellipodia, and asterisks mark radial lamellipodia), 100 μM NSC23766 (E, I, and M; arrows indicate axial lamellipodia), and 300 μM NSC23766 (F, J, and N; arrows indicate axial processes lacking lamellipodia) on laminin (D–F), PLL (H–J), or vitronectin (L–N). Under these conditions, radial lamellipodia were present only on laminin. On laminin, we observed a dose-dependent decrease in the number of SC lamellipodia. Only radial lamellipodia were decreased at intermediate doses of inhibitor (100 μM; E and G) and active Rac1 (A and B; P < 0.0001 by t test), whereas axial lamellipodia were unchanged (G; P = 0.6 by t test). In contrast, both axial and radial lamellipodia were decreased at high doses of inhibitor (300 μM; F and G) and low levels of active Rac1 (A and B). n = 100 SCs. Error bars indicate SEM. (P–S) 50 μM of inhibitor were sufficient to inhibit myelination in mouse DRG. Staining for MBP is in green, neurofilament (NF) is in red, and DAPI is in blue. Bars, 100 μm.

Activity of small Rho GTPases during peripheral nerve development

Next, we asked if the activity of Rac1, or other small GTPases, is affected in β1 integrin–null SCs and promotes axonal sorting. Both axons and SCs express small Rho GTPases, myelinating SCs at high levels (Terashima et al., 2001). We studied expression and activation of Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA in developing sciatic nerves, where SCs constitute the predominant cell type. The total protein levels of the three GTPases decreased in the adult (Fig. 4 A), whereas the active, GTP-bound fraction of the three small GTPases in sciatic nerve lysates did not change substantially during postnatal development (Fig. 4, B and C).

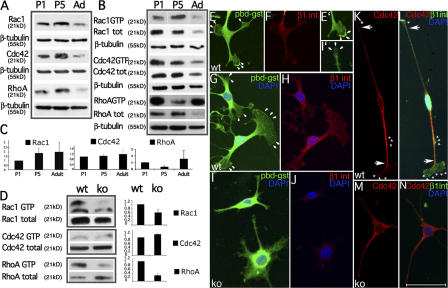

Figure 4.

Rac1 activation and membrane targeting are deficient in β1 integrin–null SCs. (A–C) Expression and activation of small Rho GTPases during nerve development. (A) Western blot on sciatic nerves lysates for Rac1, Cdc42, and Rho. (B) Pull-down assay of PDB-GST for Rac and Cdc42, and GST-Rotekin for RhoA. Active proteins were normalized to total Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA, and equal loading was verified by β-tubulin. (C) The relative levels of active Rho GTPases at P5 and in the adult were normalized to P1 levels. (D) Levels of active Rac1 in mutant nerves were normalized to total Rac1 levels and divided by relative levels of active Rac1 in wt nerves. Loading was verified by β-tubulin (not depicted). The levels of active Rac1 are reduced in β1 integrin–null nerves by about half. In similar assays, the levels of active Cdc42 were not reduced, whereas levels of active RhoA were reduced. Representative experiments from a minimum of three repetitions. Error bars indicate SEM. (E–J) SCs on laminin, treated with PBD-GST and saponin, and stained with anti-GST (green) and anti–β1 integrin (red) antibodies. The presence of PBD does not interfere with the capacity to form large lamellipodia (G). PBD is enriched at the leading edge of lamellipodia in β1 integrin–positive cells (E, arrows; enlarged in E′) but not in β1 integrin–null SCs (I; magnification in I′). (K–N) Staining of wt cells with anti-Cdc42 (K and M, red), and anti–β1 integrin antibodies (L, green; merge image in N) shows that under these conditions, Cdc42 does not contribute to the recruitment of PBD to the leading edge, as it is excluded from lamellipodia (asterisks show lamellipodia, and arrows show the restricted Cdc42 staining). (K and M) The localization of Cdc42 (green) in β1 integrin (red) negative cells is similar to that of wt cells. Bars: (E and F) 30 μm; (E′) 36 μm; (G and H) 41.4 μm; (I and J) 29 μm; (I′) 38.8 μm; (K and L) 35.8; (M and N) 50.6.

Rac1 activation and membrane targeting are impaired in β1 integrin–null nerves and SCs

To ask if mutant SCs had diminished Rac1 signaling, we compared the amount of active, GTP-bound Rac1 in sciatic nerves deriving from mutant and control mice. Relative Rac1 activity of β1 integrin–null sciatic nerves was decreased to ∼60% of wt nerves (Fig. 4 D). One way by which integrins regulate Rac1 is by promoting the translocation of GTP-bound Rac1 to the cell membrane, allowing interaction with the effector p21-activated kinase (PAK) 1 (Del Pozo et al., 2000). To test if GTP-bound Rac was able to target to the SC membrane in the absence of β1 integrin, we added purified GST–PAK binding domain (PBD) to wt or mutant SCs spreading on laminin and visualized its localization using anti-GST antibodies. We favored internalization of PBD-GST using saponin. Addition of GST alone resulted in no immunostaining (unpublished data). As expected, PBD was enriched at the surface of lamellipodia in wt cells, suggesting that active Rac1 is recruited at the leading edge of SC spreading on laminin (Fig. 4, E, E′, and G). In contrast, PBD-GST was not enriched in processes of mutant SCs (Fig. 4, I and I′). The fraction of processes with membrane enrichment was significantly lower in β1 integrin cells (121 out of 208 processes in 47 wt cells and 33 out of 114 processes in 31 null cells; P < 0.005 by χ2 analysis). This suggests that Rac1 translocation is inhibited in the absence of β1 integrin. PBD can bind also Cdc42. To evaluate whether PBD could be interacting with Cdc42 in lamellipodia, we stained wt and mutant SCs for Cdc42. Cdc42 is excluded from lamellipodia of SCs spreading on laminin (Fig. 4 K), and its localization is similar between β1 integrin–negative and –positive cells (Fig. 4 M). Thus, Cdc42 does not colocalize with PAK during lamellipodia formation on laminin. We conclude that SCs recruit active Rac1 to the membrane of lamellipodia when spreading on laminin and that this translocation is impaired in the absence of β1 integrin.

Cdc42 and RhoA activity in β1 integrin–null nerves

We next assayed the activity Cdc42 and RhoA in mutant nerves. The levels of active Cdc42 were not substantially different (Fig. 4 D), consistent with the normal localization of Cdc42 in β1-null SCs. This suggests that Cdc42 is activated independently of β1 integrins in SCs.

RhoA activity was markedly reduced in β1 integrin–null and control sciatic nerves (Fig. 4 D). Because RhoA in other cell types controls the formation of focal adhesion and stress fibers (Hall et al., 1993), we visualized them in wt and mutant SCs using phalloidin and antibodies against talin and paxillin. We could not detect any qualitative difference in focal adhesion and stress fiber formation between wt and mutant cells (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200610014/DC1).

Rac1 conditional null mice manifest delayed axonal sorting and hypomyelination

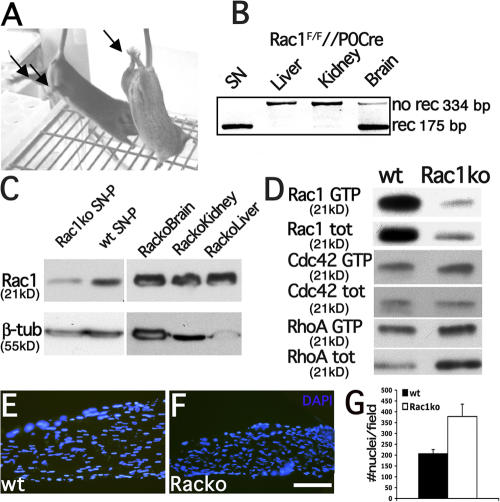

Because the absence of β1 integrin in SCs causes a reduction in lamellipodia formation and Rac1 activity and Rac1 promotes radial lamellipodia formation in SCs, we hypothesized a role for Rac1 in the formation of radial processes by SCs during axonal sorting (Webster et al., 1973). To test this, we generated mice with an SC-specific deletion of the Rac1 gene, by crossing mice bearing a conditional loxP-flanked allele of Rac1 (Rac1F) with P0-Cre transgenic mice (Feltri et al., 1999; Walmsley et al., 2003). Rac1 conditional null mice were viable but developed severe clenching and occasional paralysis of posterior limbs (Fig. 5 A). We analyzed recombination of the Rac1 locus by PCR on genomic DNA from different tissues of Rac1F/F//P0-Cre mice. As shown for other floxed loci (Feltri et al., 2002; Saito et al., 2003; Bolis et al., 2005), P0-Cre mediated specific and robust inactivation of Rac1 (Fig. 5 B) in sciatic nerves, but not liver and kidney. Recombination was also observed in brain, as previously reported for some floxed loci using this P0-Cre (Bolis et al., 2005). By Western blot analysis, the levels of Rac1 protein were reduced in mutant nerves (Fig. 5 C). We could not demonstrate the complete absence of Rac1 protein or activity in SCs by Western blot, pull-down assay, or immunohistochemistry of nerves (Fig. 5 D and not depicted), likely because Rac1 is expressed in axons and because all available anti-Rac1 antibodies also recognized the highly related Rac3 (Haataja et al., 1997). To ask whether Rac1 affected SC number, we counted the number of nuclei in P45 Rac1 mutant nerves. The number of nuclei per sciatic nerve segment was not reduced (Fig. 5, F and G). Instead, the number of nuclei was increased, as well as their density, as the mutant nerve was smaller. Cdc42 and RhoA activities were not substantially different between mutant and wt mice (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Rac1 inactivation in SCs. (A) A conditional Rac1-null mouse (right) and a control littermate (left) are shown. Mutant mice show signs of neuropathy, such as clenching of the hind limbs (arrow). (B) PCR on genomic DNA shows that the Rac floxed allele was recombined at high efficiency in peripheral nerves (no rec, nonrecombined; rec, recombined), but not in liver or kidney. (C) Western blot analysis from Rac1-null mice and control sciatic nerves show reduction of Rac1 protein in mutant nerves (densitometric value of Rac/β-tubulin = 0.3 in mutant and 0.7 in wt). Nerves were stripped of perineurium (SN-P) to reduce contribution from perineurial cells. (D) Activation assays show that low Rac1 activity (possibly due to Rac3) remains. The level of active Cdc42 and RhoA are not different between wt and Rac1-null nerves. (E and F) Longitudinal sections of sciatic nerves from wt or Rac1-null nerves stained with DAPI shows that the density of nuclei was not decreased in mutant nerves (G; 378 ± 57 nuclei/μm2 in mutant versus 207± 19 nuclei/μm2 in wt nerves; P = 0.056 by t test). Error bars indicate SEM.

Rac-deficient SCs cannot generate lamellipodia and show impaired myelination in vitro

To ask whether SCs lacking Rac1 are able to generate lamellipodia, we isolated them from postnatal day (P) 5 mutant sciatic nerves and plated them on different substrates. As observed before, wt cells generated more radial lamellipodia when plated on laminin than PLL or vitronectin. Similar to SCs lacking β1 integrin, SCs lacking Rac1 could not generate lamellipodia, but neither radial nor axial (Fig. 6). This is consistent with the fact that levels of active Rac are much lower than those of β1 integrin–null cells (Fig. 5) and agrees with the dose-dependent model proposed by Pankov et al. (2005) and our data using 300 μM NSC23766. Lack of lamellipodia was present also on vitronectin and PLL.

Figure 6.

Impaired lamellae and myelin formation by Rac1-deficient SCs in vitro. SCs isolated from P5 Rac-null (D–F) or wt (A–C) sciatic nerves were plated on laminin (A and D), PLL (B and E), or vitronectin (C and F) and stained using TRITC-conjugated phalloidin. Wt cells make more radial (asterisks) and axial (arrows) lamellipodia on laminin than on the other substrates. Both radial and axial lamellipodia formation are impaired in mutant SCs (G–I). n = 50 cell per condition. (J–N) DRG from mutant mice synthesize fewer myelin internodes per field (P < 0.01 by t test, n = 25 fields in both genotypes). Error bars indicate SEM. Bars: (A–F) 50 μm; (J–M) 100 μm.

Use of the Rac1 inhibitor prevented myelination in wt DRG (Fig. 3). To eliminate a possible neuronal intrinsic effect, we asked whether mutant DRG, lacking Rac1, specifically in SCs, could myelinate normally. The number of MBP-positive internodes was reduced significantly in mutant DRG (P < 0.01; Fig. 6, J–N).

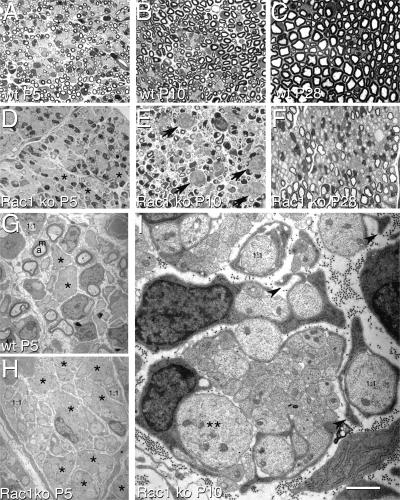

Delay of radial sorting and myelination in mice with SC-specific ablation of Rac1

We next analyzed sciatic nerve morphology by semithin and ultrathin sections during the postnatal development of Rac1F/F//P0-Cre mice and controls. In wt animals, P5 nerves contain few bundles of unsorted axons, axons in a one-to-one relationship with SCs and many thinly myelinated fibers (Fig. 7 A). In contrast, in P5 Rac1 mice, many axons were unsorted in bundles, some axons were in a one-to-one relationship, and no myelinated fibers were present (Fig. 7 D). Ultrastructural analysis at P5 confirmed that many axons were unsorted in more numerous and larger bundles in mutant than in wt littermates (Fig. 7, G and H, asterisks). In P10 wt nerves, occasional unsorted bundles were present, and myelin becomes thicker (Fig. 7 B). In contrast, several unsorted bundles of axons remained in Rac1-null nerves (Fig. 7 E, arrows), which contain axons >3 μm (Fig. 7 I, double asterisks). Many SCs began to segregate large caliber axons in a one-to-one relationship (promyelinating SCs), and several thinly myelinated fibers appeared (Fig. 7 E). Thus, developing Rac1-null nerves present a delay in axonal sorting and myelination. Many promyelinating SCs in Rac-null nerves showed bizarre and disoriented cytoplasmic processes directed away from axons (Fig. 7 I), strikingly similar to those observed in β1 integrin–null nerves (Feltri et al., 2002). By P28, unsorted axons were not detectable in mutant nerves, and there was a progressive increase in the number of myelinated fibers (Fig. 7 F). However, many large caliber axons were devoid of myelin or had thin myelin sheaths. Thus, Rac1 is required for timely radial sorting of axons by SCs, but the sorting defect can be overcome, possibly by compensation or redundancy with other GTPases such as Rac3, Cdc42, or RhoG. After reaching the promyelinating stage, albeit with delay, many Rac1-null SCs are still unable to myelinate.

Figure 7.

Inactivation of Rac1 in SCs delays sorting of axons and impairs myelination. Transverse semithin sections of wt (A–C) and mutant (D–F; Rac1 knockout [ko]) sciatic nerves at P5 (A and D), P10 (B and E), and P28 (C and F), and electron microscopy from mutant and wt sciatic nerves at P5 (G and H) and mutant nerves at P10 (I). In wt P5 nerves, few bundles of unsorted axons are still present (A and G, asterisks), whereas few fibers have SCs and axons in a one-to-one relationship (G, 1:1) and most large axons have thin myelin (A and G; a, axon; m, myelin). In contrast, P5 mutant nerves contain many large bundles of unsorted axons (D and H, asterisks), many fibers in a one-to-one relationship (D and H, 1:1), and no myelin (D and H). In P10 wt nerves, sorting is almost complete and myelin sheaths become thicker (B and not depicted). In contrast, P10 mutant nerves still contain frequent bundles of unsorted axons (E, arrows), including large caliber axons (e.g., double asterisks on an axon of 3 μm shown in I). By P10, many more one-to-one fibers are seen (E and I, 1:1) and myelination begins (E). Promyelinating SCs show aberrant processes directed away from the axon (I, arrowheads). At P28, myelination is complete in wt nerves (C). Mutant nerves show hypomyelination (F). Bar: (A–F) 20 μm; (G and H) 5 μm; (I) 1.5 μm.

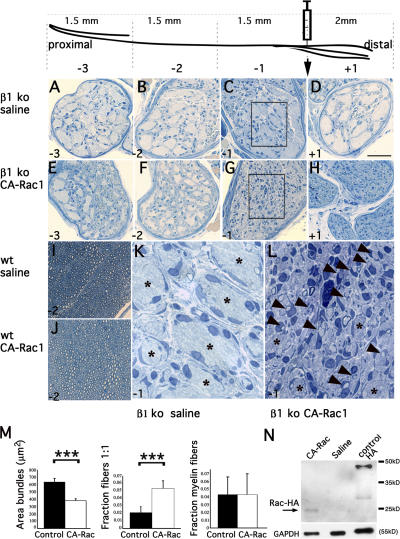

Forced Rac1 activation improves sorting in β1 integrin–null nerves

The inability to produce radial sheets of membranes as a result of deficient Rac1 activation seems to be one of the important defects of β1 integrin–null SCs. Thus, forced Rac1 activation should improve the radial sorting phenotype of β1 integrin–null nerves. To test this, we injected an adenovirus expressing constitutively active (CA) Rac1 in the endoneurium of P10 β1 integrin–null sciatic nerves. This procedure creates minimal damage to the developing nerve (Fig. 8, I and J) and allows for distant spreading of the injected virus. Contralateral nerves were injected with saline solution or adenoviruses expressing reporter genes. Remarkably, nerves treated with active Rac1 showed an improvement of sorting, as compared with control-injected nerves (Fig. 8, compare A–D with E–H). The effect was most evident near the site of injection (−1 and +1), where many naked bundles of axons were reduced in size, and they contained fibers in a one-to-one relationship with promyelinating SCs or thin myelin sheaths (Fig. 8, G and H; compare enlarged magnifications in L with K). Statistical analysis performed on optic and electron microscopic sections of the −1 level confirmed that radial sorting was significantly improved, as the size of unsorted bundles decreased (P < 0.01) and the proportion of promyelinating SCs (fibers in a one-to-one relationship) increased (P < 0.02). In contrast, the proportion of myelinated fibers did not change, suggesting that the levels of active Rac1 achieved were sufficient for radial sorting but not for myelination. The active Rac construct is fused to an HA tag, which allowed us to confirm its expression in injected nerves by Western blotting (Fig. 8 N).

Figure 8.

Infection with an adenovirus expressing CA-Rac1 improves the sorting phenotype of β1 integrin conditional null nerves. Adenoviruses expressing CA-Rac1 were injected into the endoneurium of β1 integrin–null or wt P10 sciatic nerves at the common peroneal/tibialis bifurcation. At P22, transverse semithin sections were examined 2 mm distal (+1; D and H) or 1.5 mm (−1; C, G, K, and L), 3 mm (−2; B, F, I, and J), and 4.5 mm (−3; A and E) proximal to the injection site. At this age, injection of adenovirus or saline produced minimal damage or inflammation in wt (I and J) and mutant (A–H, K, and L) nerves. In mutant nerves treated with CA-Rac1, the number and extension of bundles of unsorted axons was reduced as compared with saline-treated nerves (compare E–H to A–D, respectively). The effect was more obvious near the injection site (−1 and +1). Here, as shown in the enlarged inset of C and G, many axons in the bundles had been sorted, ensheathed, and even thinly myelinated (compare L with K). Asterisks in K and L indicate unsorted axon bundles, and arrowheads point to one-to-one promyelinating fibers. (M) Quantification of the rescue. The area of unsorted bundles significantly decreased in CA-Rac1–treated nerves (P < 0.0001 by t test, n = 278 [control] and 305 [CA-Rac1] bundles). Although the fraction of one-to-one fibers significantly increased in CA-Rac1–injected nerves (P < 0.02 by t test; n = 7 animals), the number of myelinated fibers did not. Error bars indicate SEM. (N) Expression of the HA-tagged CA-Rac1 virus confirmed by Western blot analysis. HA-Rac was expressed in nerves injected with CA-Rac at the expected size, but not in nerves injected with saline. Control HA shows the positive control for the HA antibodies (lysates from cells transfected with a construct coding for a different HA fusion protein). Bar: (A–J) 50 μm; (K and L) 9 μm.

Defects in Rac1-null nerves and Rac1-mediated rescue in β1 integrin–null nerves are not mediated by inside-out effects on the basal lamina

To ask whether the abnormalities in Rac-null nerves could be due to basal lamina defects, we compared the basal laminae of adult mutant and wt nerves by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Staining with antibody to α2, α4, and γ1 laminin chain and to collagen IV did not reveal abnormalities in mutant nerves. A subset of fibers in Rac-null sciatic nerves showed higher α4 laminin immunoreactivity, probably because of their immaturity (Fig. S5 F, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200610014/DC1). Basal laminae appeared normal ultrastructurally (Fig. S5, I and J). Similarly, we asked if Rac activation in rescued β1 integrin–null nerves had an effect on the basal lamina. β1 integrin–null nerves contain both fibers with normal and redundant basal lamina (Fig. S5, K and M; Feltri et al., 2002). Similarly, CA-Rac rescued nerves contained both normal (Fig. S5, L′) and redundant (Fig. S5, N′) basal laminae around nerve fibers. Thus, basal laminae abnormalities do not seem to account for the delay in myelination seen in Rac-null nerves or for the rescue by Rac1 seen in β1 integrin–null nerve.

Discussion

Axonal sorting is a key step in the development of the peripheral nervous system. It is well established that laminins and β1 integrins are required for radial axonal sorting (Feltri et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2005b), but which signaling pathways are activated is largely unknown. We have presented evidence that the segregation of axons by SCs is dependent on activation of the small GTPase Rac1 by β1 integrin. The levels of Rac1 activity in several cell types control extension of radial lamellae. Accordingly, Rac1 membrane targeting and activation are deficient, and SCs cannot extend radial processes in the absence of β1 integrin or when Rac activity is decreased. Furthermore, targeted inactivation of Rac1 in SCs delays radial sorting and impairs myelination. Finally, increasing levels of activated Rac1 in nerves lacking β1 integrin improves sorting. We conclude that Rac1 in SCs is required for the extension of cytoplasmic processes that surround axons during radial sorting and then wrap them during myelination.

Cell shape abnormalities in β1-null SCs

Inactivation of laminins or β1 integrin in SCs of transgenic mice causes an arrest in radial sorting (Feltri et al., 2002). Radial sorting requires first that the number of SCs match the number of axons and then that SCs change their shape to allow extension of processes around axons. Although laminin deficiency in SCs impairs proliferation (Yang et al., 2005) and survival (Yu et al., 2005b), these parameters are preserved in the absence of β1 integrins, suggesting that a β1-containing receptor promotes sorting by regulating changes in shape (Feltri et al., 2002). Here, we show that one abnormality in β1 integrin–deficient SCs is indeed in their ability to spread. Specifically, the surface area and the number of lamellipodia are decreased in β1 integrin–null cells and peripheral, but not axial, lamellipodia are affected. Because SCs must insert cytoplasmic lamellae radially among axons during radial sorting, we suggest that this is one major impairment in β1-null nerves. It is possible that laminins use a different receptor to regulate SC proliferation and survival.

Spatial localization of Rac1 activation in SCs during axonal sorting

Rac1 activation and membrane translocation are impaired in β1 integrin–deficient SCs. This suggests that β1 integrins in SCs regulate Rac1 activation and membrane targeting and is consistent with data in several cell systems showing that β1 integrins regulate Rac1 (Cox et al., 2001; Suzuki-Inoue et al., 2001; Hirsch et al., 2002; Miao et al., 2002; Laforest et al., 2005; Pankov et al., 2005). These data could imply that β1 integrin in SCs is located at the leading edge of the advancing lamellipodia, which is in contact with axons during radial sorting. However, this is hard to reconcile with the fact that laminin mutants have a similar sorting phenotype (for review see Colognato et al., 2005), and laminins are in the basal lamina and thus located on the outer surface of the SC, away from the axon. At least three possibilities can explain this discrepancy. First, laminins at the time of radial sorting (E17.5 to P5 in the mouse) could also be present at the SC surface contacting the axon. Although the resolution of staining in SC processes contacting an axon bundle precludes a certain answer, this hypothesis is supported by the fact that SCs secrete laminins (Bunge et al., 1986) and that laminins may not need to be organized in a basal lamina for radial sorting to occur (for review see Feltri and Wrabetz, 2005). Second, laminins could initiate a transcellular signal that affects apical (in this case near the axon) surfaces. This has been shown in epithelial cysts, where laminin polymerization at the basal surface directs polarization of the apical surface via Rac1 (Ojakian and Schwimmer, 1994; Yu et al., 2005a). Another example showing that laminins in SCs control events at the adaxonal surface, possibly through transcellular signaling, is the clustering of voltage-gated sodium channels on the axon (Occhi et al., 2005). The final possibility is that laminins mediate sorting through a different mechanism (e.g., regulation of proliferation) and that β1 participates in sorting via a nonlaminin receptor, such as α4β1 or α5β1 integrin.

Role of Rac1 and other Rho GTPases in nerve development

The generation of Rac1 conditional null mice shows that Rac1 is involved both in axonal sorting and myelination. The block in axonal sorting is transient and then some cells are blocked again at the promyelinating stage. As a result, many axons remain devoid of myelin, and the remaining axons are hypomy elinated. Probably the absence of Rac1 first impairs the formation of radial/peripheral processes that are necessary for the first steps of axonal sorting. A successive up-regulation or activation of other small GTPases (such as Rac3 or RhoG) may compensate at activity levels that are sufficient for the formation of radial lamellae of the appropriate size for sorting, but not large enough for wrapping during myelination. A redundancy with Rac3 or RhoG may thus potentially explain the differences in the severity of sorting observed between Rac1 and β1 integrin mutant nerves. In addition, other molecules are likely to promote radial sorting downstream of β1 integrins. Mice lacking focal adhesion kinase in SCs have recently been reported and have a radial sorting phenotype very similar to that of β1 integrin mice (except for minor differences probably due to the timing of Cre recombination; Grove et al., 2007). Because Cdc42 and Rac1 cooperate in many cell types, it was surprising to find that Cdc42 activity was not reduced in β1 integrin conditional null mice. Cdc42 controls filopodia formation (Nobes and Hall, 1995), and SCs use filopodia-like structures to explore axons during initial interactions (Gatto et al., 2003). We showed that both these filopodia-like structures and Cdc42 localization are normal in β1-null SCs. Because Cdc42 is important for a cell to initiate its polarization, by acting on microtubule (for review see Hall, 2005), it is possible that these events are required for axonal sorting, but they precede the activation of β1 integrin and Rac1 in SCs. Thus, we may have not observed an effect on Cdc42 because P0-Cre–mediated β1 recombination occurred after E17.5. Alternatively, these results indicate that β1 integrins activate Rac1 during axonal sorting, whereas Cdc42 is activated through another signaling pathway (see Benninger et al. on p. 1051 of this issue). Finally, the levels of active RhoA were markedly reduced in β1 integrin–null nerves, suggesting that RhoA is also involved in SC development downstream of β1 integrins. The role of RhoA in nerve development remains to be examined.

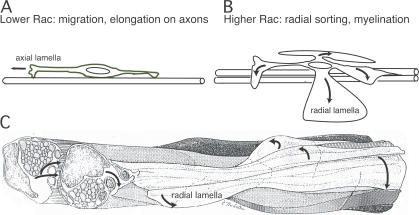

β1 integrins signal via Rac1 to regulate SC shape during radial sorting of axons

Small interfering RNA–mediated reduction of Rac1 showed that modulation of Rac1 activity controls the decision between directionally persistent and random migration in cultured epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Low levels of active Rac1 promote the formation of axial lamellae at the extremities of the cell-long axis and favor directed migration. In contrast, increasing levels of active Rac1 favor the formation of peripheral lamellae with random migration and spreading (Pankov et al., 2005). Here, we show that this is also true for cultured SCs. More important, we provide the first application of this model in vivo in developing SCs. We propose that a progressive rise in Rac1 activation regulates the transition from migration/elongation to the arrest of migration and the wrapping of axons (Fig. 9). Interestingly, the cellular phenotype of β1 integrin–null cells is opposite to that of SCs deficient in merlin/Schwannomin, the tumor suppressor mutated in neurofibromatosis 2. Merlin is a negative regulator Rac1 (Shaw et al., 2001; Kissil et al., 2003), and loss of merlin in patients leads to Rac1 hyperactivation in SCs (Kaempchen et al., 2003), impeding elongation on axons (Nakai et al., 2006). Merlin is recruited to the cell membrane, where it interacts with β1 integrin (Fernandez-Valle et al., 2002). We suggest that the association with β1 integrin is inhibitory for merlin, permitting controlled activation of Rac1.

Figure 9.

Model for β1 integrin–mediated Rac1 activation in peripheral nerve development. (A) Low levels of Rac generate axial lamellipodia during SC migration and elongation on axons. (B) Increase in Rac levels generates several radial/peripheral lamellipodia (curved arrows) that allow SCs to sort and myelinate axons. (C) Reconstruction of an SC during radial axonal sorting in newborn nerve (modified from Webster, H.D., R. Martin, and M.E. O'Connell. 1973. Dev. Biol. 32:401–416 with permission from Elsevier), showing the radial cytoplasmic processes (lamellae; curved arrows) between and around axons. We propose that, similar to radial lamellipodia in cultured cells, the switch from longitudinal elongation to radial process extension is mediated by β1 integrins via activation of Rac1.

How SCs “choose” the axons to be sorted and myelinated is still unknown. This fate of axons is related to neuregulin-1 type III levels they express, which leads to the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in SCs (Michailov et al., 2004; Taveggia et al., 2005). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase also activates the Rac1 pathway, and it is likely that a cooperation between laminin- and neuregulin-driven mechanisms control axonal sorting and or myelination.

Materials and methods

Transgenic and mutant mice

Experiments with animals followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of San Raffaele Scientific Institute. mP0TOTA (P0-Cre), floxed β1 integrin (β1F/F; obtained from U. Mueller, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), and floxed Rac1 (Rac1F/F) were described previously (Feltri et al., 1999, 2002; Walmsley et al., 2003). P0-Cre, β1+/− and β1F/+ mice were N15-N18 generations congenic in C57BL/6, whereas Rac1F/F P0-Cre mice and littermate controls were F2. Crosses to generate conditional null mice were either YF/+//P0-Cre × YF/F or Y+/−//P0-Cre × YF/F. Genotypes were identified by PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA (Feltri et al., 1999). Primers for recombination of the floxed Rac1 allele were as follows: 5′-ATTTTGTGCCAAGGACAGTGACAAGCT-3′, 5′-GAAGGAGAAGAAGCTGACTCCCATC-3′, and 5′-CAGCCACAGGCAATGACAGATGTTC-3′, which amplify a 175- (recombined), 300- (wt), or 334- (floxed allele) nucleotide band. Given the multiplex nature of the PCR amplification, the band intensity cannot be used to judge the amount of recombination.

Organotypic neuron/SC cocultures

Mouse E14.5 DRG were dissected as described previously (Kleitman et al., 1991) and maintained in N/D Sato medium (modified from Cosgaya et al., 2002). Myelination was induced with 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). Time-lapse analysis was performed on glass-bottomed 35-mm plates (Mat-Tek), using an inverted microscope (Axiovert; Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc.). Images were captured every 60 s, for a maximum of 2 h, by a charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu) and analyzed with ImageJ. Recorded cells were identified by drawing on the plate with a diamond tip and retrospectively stained for β1 integrin.

Cold jet

SCs were purified from DRG cultures by the cold jet technique (Jirsova et al., 1997), plated in N/D Sato, and stained after 24 h.

SC purification

Mouse SCs were isolated from P5 sciatic nerves stripped of perineurium using 4% collagenase and 2.5% trypsin, plated on coverslip in defined medium (Parkinson et al., 2001) with 10 ng/ml β-neuregulin-1 (R&D Systems) and 2 μm forskolin (Calbiochem), and analyzed after 24 h.

Rac1 pharmacological inhibition

Rat SCs were plated on laminin in DME and 10% fetal calf serum for 2 h, treated with NSC23766 (Gao et al., 2004; provided by Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutic Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, Bethesda, MD) in defined medium for 30 or 120 min, and stained with phalloidin or assayed for Rac1 activity. For myelination, NSC23766 was added to mouse DRG during ascorbic acid treatment.

Immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (Feltri et al., 2002). Immunocytochemistry was performed on glass coverslips, coated with PLL alone (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.1 mg/ml, or followed by coating with 10 μg/ml vitronectin or laminin 1 (Sigma-Aldrich). Purified mouse SCs or DRG were fixed in 4% PFA or in dodecyl-trimethylammonium chloride + 1% PFA (Nakamura, 2001) and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) or 100% methanol. To reveal active Rac1 localization, recombinant PAK1 PBD-GST protein was detected with an anti-GST antibody. PAK1 PBD-GST was added at a final concentration of 0.01 μg/μl. After 5–6 h, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at RT, permeabilized with 0.2% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich)/0.2% gelatin gepulvert (Merck), and reexposed to PAK PBD-GST at 0.01 μg/μl diluted in 0.1% saponin/0.2% gelatin overnight at 4°C. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% saponin/0.2% gelatin. GST alone was used as a negative control. Negative controls for β1 integrin staining were β1 integrin–deficient “TKO” embryoid cells (Stephens et al., 1993).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti–Neurofilament H (Chemicon); rat anti-Neurofilament (TA-51; a gift from V. Lee, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA); mouse anti–Neurofilament M (Roche and Chemicon); rabbit anti–β1 integrin (a gift from K. Rubin, University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden); goat anti-paxillin antibody, goat anti-talin antibody, rabbit anti-Rac1, mouse anti-RhoA, and rabbit anti-Cdc42 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); goat anti-GST (GE Healthcare); mouse anti-Rac1 (Upstate Biotechnology and BD Biosciences); mouse anti–β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit anti–S-100 (DakoCytomation); rat anti–laminin α2 (a gift from L. Sorokin, Lund University, Lund, Sweden); rabbit anti–laminin α4 (a gift from J. Miner); and peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA antibodies (Roche). Secondary antibodies were conjugated with FITC, TRITC, or Cy5 fluorochromes (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories and Sothern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.).

Western blotting and Rho GTPase assays

GST pull-down assays for Rho GTPases were performed for Rac and Cdc42 as described previously (Benard et al., 1999) using a pGEX-cRac1A plasmid (a gift from G. Bokoch, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), and for RhoA using Rhotekin RBD-GST plasmid (a gift from C. Laudanna, University of Verona, Verona, Italy) as described by Giagulli et al. (2004), with few modifications. Lysates from sciatic nerves at P1, P5, and adult mice or from SCs were triturated in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 5 mM MgCl2 with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After centrifugation, 500 μg of lysates were incubated either with 17 μg PAK1 PBD-GST or 35 μg Rhotekin RBD-GST bound to glutathione agarose for 60 min at 4°C. Lysates activated or inactivated with GTP-γs or GDP-βs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Beads were washed once in lysis buffer and, together with total lysates (10 μg for Rac1 and Cdc42 and 20 μg for RhoA), heated for 5 min at 100°C in reducing sample buffer and processed for Western blotting by standard methods. For quantification, films were digitalized and analyzed using ImageQuant v1.2 for Mac software (Molecular Dynamics). Images for comparison were always on the same gel.

Adenovirus injection

1.5 μl adenovirus-Rac1CA (1012 virions/ml; a gift from M. Resh [Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY]; Liang et al., 2004), saline, or adenoviruses expressing GFP of LacZ were injected in the endoneurium of P10 sciatic nerve of anesthetized mice (seven animals total). Nerves were collected after 12 d. To quantify the rescue, the mean area of all bundles of unsorted axons present in transverse semithin section of the complete −1 levels from seven different experiments were measured using ImageJ. Promyelinating and myelinating axons were counted as a proportion of total nerve fibers in 10 random electron microscopic fields from the −1 levels in seven CA-Rac1–injected and seven control nerves.

Morphological analysis

Morphological analyses of nerves were conducted as described previously (Wrabetz et al., 2000).

Image acquisition and analysis

Images were acquired using confocals (UltraView ERS spinning disk confocal microscope [PerkinElmer] equipped with a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil-immersion objective and using the UltraView acquisition software; TCS-SP5 [Leica] equipped with a Plan Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil-immersion objective and using the LCS confocal acquisition software [Leica]; or Confocal-MRC 1024 laser-scanning confocal microscope [Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.] equipped with a Plan Neofluar 40×/1.3 oil-immersion objective and using the Laser Sharp 2000 acquisition software) or a camera (DFC480 R2; Leica) mounted on a fluorescence microscope (DM 5000 B; Leica) equipped with N Plan 10×/0.25, HC PL Fluotar 20×/0.50, and HCX PL Fluotar 40×/0.75 objectives, using Firecam software (Leica). Videos were acquired using a camera (Orca II; Hamamatsu) mounted on a microscope (Axiovert S100 TV2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) equipped with a Plan Neofluar 40×/1.3 oil-immersion objective at 37°C in Eagle's minimum essential medium with 10% FCS and 25 mM Hepes, without phenol red, with or without ascorbic acid, and using the Image Pro-Plus 4.5 acquisition software. Electron microscopy sections were visualized and photographed using a transmission electron microscope (EM900; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Films were digitalized using a scanner (Arcus II; Agfa-Gevaert). Image processing and quantification was performed using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe) or ImageJ (v1.33u). Adjustment of brightness or contrast was used in some cases but without obscuring, eliminating, or misrepresenting information. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Office X; Microsoft), Stat View (v5.0), and SPSS v11.

Online supplemental material

Videos 1 and 2 show a wt and a β1 integrin–null SC, respectively, migrating on a DRG axon in a qualitatively similar manner. Videos 3 and 4 show a wt and a β1 integrin–null SC, respectively, interacting with axons in a similar fashion. Fig. S1 shows that the cells in Videos 2 and 4 were negative for β1 integrin. Fig. S2 shows still frames from Videos 1–4. Fig. S3 shows that stress fibers and focal adhesions appear normal in β1 integrin–null SCs. Fig. S4 shows the method used to quantify PAK PBD-GST enrichment in the cell membrane. Fig. S5 shows that basal laminae are normal in Rac1-null nerves and in CA-Rac rescued β1 integrin–null nerves. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200610014/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Ferri for excellent technical assistance; Alembic for image acquisition; U. Mueller for β1 integrin floxed mice; M. Resh for active Rac1; V. Lee, K. Rubin, L. Sorokin, and J. Miner for antibodies; C. Laudanna and G. Bokoch for GTPase effector plasmids; and J. Relvas (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zurich) for sharing data before publication.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS045630 and NS055256), Telethon, Italy (GGP04019 and GGP030074), and the Medical Research Council, UK.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CA, constitutively active; DRG, dorsal root ganglia; E, embryonic day; MBP, myelin basic protein; P, postnatal day; PAK, p21-activated kinase; PBD, PAK binding domain; PLL, poly-l-lysine; SC, Schwann cell; wt, wild-type.

References

- Benard, V., B.P. Bohl, and G.M. Bokoch. 1999. Characterization of rac and cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13198–13204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninger, Y., T. Thurnerr, J. Pereira, S. Krause, X. Wu, A. Chrostek-Grashoff, D. Herzog, K.-A. Nave, R.J.M. Franklin, D. Meijer, et al. 2007. Essential and distinct codes for cdc42 and rac1 in the regulation of Schwann cell biology during peripheral nervous system development. J. Cell. Biol. 177:1051–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolis, A., S. Coviello, S. Bussini, G. Dina, C. Pardini, S.C. Previtali, M. Malaguti, P. Morana, U. Del Carro, M.L. Feltri, et al. 2005. Loss of Mtmr2 phosphatase in Schwann cells but not in motor neurons causes Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4B1 neuropathy with myelin outfoldings. J. Neurosci. 25:8567–8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, W.G., and M. Jenkison. 1973. Abnormalities of peripheral nerves in murine muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 18:227–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge, R.P., M.B. Bunge, and C.F. Eldridge. 1986. Linkage between axonal ensheathment and basal lamina production by Schwann cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 9:305–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato, H., C. ffrench-Constant, and M.L. Feltri. 2005. Human diseases reveal novel roles for neural laminins. Trends Neurosci. 28:480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgaya, J.M., J.R. Chan, and E.M. Shooter. 2002. The neurotrophin receptor p75NTR as a positive modulator of myelination. Science. 298:1245–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, E.A., S.K. Sastry, and A. Huttenlocher. 2001. Integrin-mediated adhesion regulates cell polarity and membrane protrusion through the Rho family of GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, M.A., L.S. Price, N.B. Alderson, X.D. Ren, and M.A. Schwartz. 2000. Adhesion to the extracellular matrix regulates the coupling of the small GTPase Rac to its effector PAK. EMBO J. 19:2008–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, M.A., W.B. Kiosses, N.B. Alderson, N. Meller, K.M. Hahn, and M.A. Schwartz. 2002. Integrins regulate GTP-Rac localized effector interactions through dissociation of Rho-GDI. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo, M.A., N.B. Alderson, W.B. Kiosses, H.H. Chiang, R.G. Anderson, and M.A. Schwartz. 2004. Integrins regulate Rac targeting by internalization of membrane domains. Science. 303:839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einheber, S., T. Milner, F. Giancotti, and J. Salzer. 1993. Axonal regulation of Schwann cell integrin expression suggests a role for α6β4 in myelination. J. Cell Biol. 123:1223–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri, M.L., and L. Wrabetz. 2005. Laminins and their receptors in Schwann cells and hereditary neuropathies. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 10:128–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri, M.L., S.S. Scherer, R. Nemni, J. Kamholz, H. Vogelbacker, M.O. Scott, N. Canal, V. Quaranta, and L. Wrabetz. 1994. β4 integrin expression in myelinating Schwann cells is polarized, developmentally regulated and axonally dependent. Development. 120:1287–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri, M.L., M. D'Antonio, S. Previtali, M. Fasolini, A. Messing, and L. Wrabetz. 1999. P0-Cre transgenic mice for inactivation of adhesion molecules in Schwann cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 883:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri, M.L., D. Graus Porta, S.C. Previtali, A. Nodari, B. Migliavacca, A. Cassetti, A. Littlewood-Evans, L.F. Reichardt, A. Messing, A. Quattrini, et al. 2002. Conditional disruption of β1 integrin in Schwann cells impedes interactions with axons. J. Cell Biol. 156:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle, C., L. Gwynn, P.M. Wood, S. Carbonetto, and M.B. Bunge. 1994. Anti-beta 1 integrin antibody inhibits Schwann cell myelination. J. Neurobiol. 25:1207–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle, C., Y. Tang, J. Ricard, A. Rodenas-Ruano, A. Taylor, E. Hackler, J. Biggerstaff, and J. Iacovelli. 2002. Paxillin binds schwannomin and regulates its density-dependent localization and effect on cell morphology. Nat. Genet. 31:354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y., J.B. Dickerson, F. Guo, J. Zheng, and Y. Zengh. 2004. Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:7618–7623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto, C.L., B.J. Walker, and S. Lambert. 2003. Local ERM activation and dynamic growth cones at Schwann cell tips implicated in efficient formation of nodes of Ranvier. J. Cell Biol. 162:489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giagulli, C., E. Scarpini, L. Ottoboni, S. Narumiya, E.C. Butcher, G. Constantin, and C. Laudanna. 2004. RhoA and zeta PKC control distinct modalities of LFA-1 activation by chemokines: critical role of LFA-1 affinity triggering in lymphocyte in vivo homing. Immunity. 20:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove, M., N.H. Komiyama, K.A. Nave, S.G. Grant, D.L. Sherman, and P.J. Brophy. 2007. FAK is required for axonal sorting by Schwann cells. J. Cell Biol. 176:277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja, L., J. Groffen, and N. Heisterkamp. 1997. Characterization of RAC3, a novel member of the Rho family. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20384–20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. 2005. Rho GTPases and the control of cell behaviour. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A., H.F. Paterson, P. Adamson, and A.J. Ridley. 1993. Cellular responses regulated by rho-related small GTP-binding proteins. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 340:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, E., L. Barberis, M. Brancaccio, O. Azzolino, D. Xu, J.M. Kyriakis, L. Silengo, F.G. Giancotti, G. Tarone, R. Fassler, and F. Altruda. 2002. Defective Rac-mediated proliferation and survival after targeted mutation of the β1 integrin cytodomain. J. Cell Biol. 157:481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen, K.R., and R. Mirsky. 2005. The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6:671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirsova, K., P. Sodaar, V. Mandys, and P.R. Bar. 1997. Cold jet: a method to obtain pure Schwann cell cultures without the need for cytotoxic, apoptosis-inducing drug treatment. J. Neurosci. Methods. 78:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaempchen, K., K. Mielke, T. Utermark, S. Langmesser, and C.O. Hanemann. 2003. Upregulation of the Rac1/JNK signaling pathway in primary human schwannoma cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12:1211–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissil, J.L., E.W. Wilker, K.C. Johnson, M.S. Eckman, M.B. Yaffe, and T. Jacks. 2003. Merlin, the product of the Nf2 tumor suppressor gene, is an inhibitor of the p21-activated kinase, Pak1. Mol. Cell. 12:841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleitman, N., P.M. Wood, and R.P. Bunge. 1991. Tissue culture methods for the study of myelination. In Culturing Nerve Cells. Bradford, Cambridge, MA. 337–377.

- Laforest, S., J. Milanini, F. Parat, J. Thimonier, and M. Lehmann. 2005. Evidences that beta1 integrin and Rac1 are involved in the overriding effect of laminin on myelin-associated glycoprotein inhibitory activity on neuronal cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 30:418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X., N.A. Draghi, and M.D. Resh. 2004. Signaling from integrins to Fyn to Rho family GTPases regulates morphologic differentiation of oligodendrocytes. J. Neurosci. 24:7140–7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Vasquez, C.V., S. Einheber, and J.L. Salzer. 2004. Rho kinase regulates Schwann cell myelination and formation of associated axonal domains. J. Neurosci. 24:3953–3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, H., S. Li, Y.L. Hu, S. Yuan, Y. Zhao, B.P. Chen, W. Puzon-McLaughlin, T. Tarui, J.Y. Shyy, Y. Takada, et al. 2002. Differential regulation of Rho GTPases by β1 and β3 integrins: the role of an extracellular domain of integrin in intracellular signaling. J. Cell Sci. 115:2199–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailov, G.V., M.W. Sereda, B.G. Brinkmann, T.M. Fischer, B. Haug, C. Birchmeier, L. Role, C. Lai, M.H. Schwab, and K.A. Nave. 2004. Axonal neuregulin-1 regulates myelin sheath thickness. Science. 304:700–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, Y., Y. Zheng, M. MacCollin, and N. Ratner. 2006. Temporal control of Rac in Schwann cell-axon interaction is disrupted in NF2-mutant schwannoma cells. J. Neurosci. 26:3390–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, F. 2001. Biochemical, electron microscopic and immunohistological observations of cationic detergent-extracted cells: detection and improved preservation of microextensions and ultramicroextensions. BMC Cell Biol. 2:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobes, C.D., and A. Hall. 1995. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 81:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occhi, S., D. Zambroni, U. Del Carro, S. Amadio, K. Campbell, F. Saito, Z. Chen, S. Strickland, E. Sirkowski, S. Scherer, et al. 2005. Both laminin and Schwann cell dystroglycan are necessary for proper clustering of sodium channels at nodes of Ranvier. J. Neurosci. 25:9418–9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojakian, G.K., and R. Schwimmer. 1994. Regulation of epithelial cell surface polarity reversal by beta 1 integrins. J. Cell Sci. 107:561–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov, R., Y. Endo, S. Even-Ram, M. Araki, K. Clark, E. Cukierman, K. Matsumoto, and K.M. Yamada. 2005. A Rac switch regulates random versus directionally persistent cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 170:793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, D., Z. Dong, H. Bunting, J. Whitfield, C. Meier, H. Marie, R. Mirsky, and K.R. Jessen. 2001. Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) mediates Schwann cell death in vitro and in vivo: examination of c-Jun activation, interactions with survival signals, and the relationship of TGFβ-mediated death to Schwann cell differentiation. J. Neurosci. 21:8572–8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, F., S.A. Moore, R. Barresi, M.D. Henry, A. Messing, S.E. Ross-Barta, R.D. Cohn, R.A. Williamson, K.A. Sluka, D.L. Sherman, et al. 2003. Unique role of dystroglycan in peripheral nerve myelination, nodal structure, and sodium channel stabilization. Neuron. 38:747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepp, K.J., and V.J. Auld. 2003. RhoA and Rac1 GTPases mediate the dynamic rearrangement of actin in peripheral glia. Development. 130:1825–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.J., J.G. Paez, M. Curto, A. Yaktine, W.M. Pruitt, I. Saotome, J.P. O'Bryan, V. Gupta, N. Ratner, C.J. Der, et al. 2001. The Nf2 tumor suppressor, merlin, functions in Rac-dependent signaling. Dev. Cell. 1:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, D.L., and P.J. Brophy. 2005. Mechanisms of axon ensheathment and myelin growth. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6:683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, L.E., J.E. Sonne, M.L. Fitzgerald, and C.H. Damsky. 1993. Targeted deletion of β1 integrins in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells affects morphological differentiation but not tissue-specific gene expression. J. Cell Biol. 123:1607–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, C.A. 1975. Abnormalities in Schwann cell sheaths in spinal nerve roots of dystrophic mice. J. Anat. 119:169–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki-Inoue, K., Y. Yatomi, N. Asazuma, M. Kainoh, T. Tanaka, K. Satoh, and Y. Ozaki. 2001. Rac, a small guanosine triphosphate-binding protein, and p21-activated kinase are activated during platelet spreading on collagen-coated surfaces: roles of integrin α2β1. Blood. 98:3708–3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveggia, C., G. Zanazzi, A. Petrylak, H. Yano, J. Rosenbluth, S. Einheber, X. Xu, R.M. Esper, J.A. Loeb, P. Shrager, et al. 2005. Neuregulin-1 type III determines the ensheathment fate of axons. Neuron. 47:681–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima, T., H. Yasuda, M. Terada, S. Kogawa, K. Maeda, M. Haneda, A. Kashiwagi, and R. Kikkawa. 2001. Expression of Rho-family GTPases (Rac, cdc42, RhoA) and their association with p-21 activated kinase in adult rat peripheral nerve. J. Neurochem. 77:986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiper, M.V., and P.D. Yurchenco. 2002. Laminin assembles into separate basement membrane and fibrillar matrices in Schwann cells. J. Cell Sci. 115:1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, M.J., S.K. Ooi, L.F. Reynolds, S.H. Smith, S. Ruf, A. Mathiot, L. Vanes, D.A. Williams, M.P. Cancro, and V.L. Tybulewicz. 2003. Critical roles for Rac1 and Rac2 GTPases in B cell development and signaling. Science. 302:459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster, H.D., R. Martin, and M.F. O'Connell. 1973. The relationships between interphase Schwann cells and axons before myelination: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Dev. Biol. 32:401–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrabetz, L., M. Feltri, A. Quattrini, D. Inperiale, S. Previtali, M. D'Antonio, R. Martini, X. Yin, B. Trapp, L. Zhou, et al. 2000. P0 overexpression causes congenital hypomyelination of peripheral nerve. J. Cell Biol. 148:1021–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, J., Y. Miyamoto, A. Tanoue, E.M. Shooter, and J.R. Chan. 2005. Ras activation of a Rac1 exchange factor, Tiam1, mediates neurotrophin-3-induced Schwann cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:14889–14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., J. Bierman, Y.S. Tarumi, Y.P. Zhong, R. Rangwala, T.M. Proctor, Y. Miyagoe-Suzuki, S. Takeda, J.H. Miner, L.S. Sherman, et al. 2005. Coordinate control of axon defasciculation and myelination by laminin-2 and -8. J. Cell Biol. 168:655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W., A. Datta, P. Leroy, L.E. O'Brien, G. Mak, T.S. Jou, K.S. Matlin, K.E. Mostov, and M.M. Zegers. 2005. a. Beta1-integrin orients epithelial polarity via Rac1 and laminin. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:433–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.M., M.L. Feltri, L. Wrabetz, S. Strickland, and Z.L. Chen. 2005. b. Schwann cell-specific ablation of laminin gamma1 causes apoptosis and prevents proliferation. J. Neurosci. 25:4463–4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.