Abstract

Attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle has been proposed to require dynamic microtubules that randomly search three-dimensional space and become stabilized upon capture by kinetochores. In this study, we test this model by examining chromosome capture in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants with attenuated microtubule dynamics. Although viable, these cells are slow to progress through mitosis. Preanaphase cells contain a high proportion of chromosomes that are attached to only one spindle pole and missegregate in the absence of the spindle assembly checkpoint. Measurement of the rates of chromosome capture and biorientation demonstrate that both are severely decreased in the mutants. These results provide direct evidence that dynamic microtubules are critical for efficient chromosome capture and biorientation and support the hypothesis that microtubule search and capture plays a central role in assembly of the mitotic spindle.

Introduction

Since its discovery >20 yr ago, microtubule dynamics has been thought to be critical for the function of microtubules in their many roles in the cell. In particular, the attachment of chromosomes to the mitotic spindle has been proposed to require dynamic microtubules that randomly search three-dimensional space and become stabilized upon capture by kinetochores (Kirschner and Mitchison, 1986). This idea has been conceptually verified by quantitative modeling (Holy and Leibler, 1994), and imaging experiments have observed the capture of elongating microtubules by chromosomes (Hayden et al., 1990; Tanaka et al., 2005). More recent evidence suggests that the process of chromosome capture may not be entirely random (Wollman et al., 2005). Chromosomes can influence microtubule assembly by establishing a local gradient of Ran-GTP (Gruss and Vernos, 2004; Zheng, 2004), and the biorientation of chromosomes may be aided by the directed movement of monooriented chromosomes to the metaphase plate (Kapoor et al., 2006). Nonetheless, the central role of microtubule dynamics is stressed in nearly every model of spindle assembly. However, there is almost no experimental evidence assessing the requirement for dynamic microtubules in this process. In this study, we demonstrate that dynamic microtubules are essential for the efficient capture and bipolar attachment of chromosomes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Results and discussion

tub2-V169A, a mutation in yeast β-tubulin, attenuates microtubule dynamics

Microtubule dynamics rely on the ability of β-tubulin to bind and hydrolyze GTP (Desai and Mitchison, 1997). In an effort to obtain strains that have altered microtubule dynamics, we changed to alanine each of 12 amino acids in yeast β-tubulin (Tub2) that interact directly with GTP (Fig. 1; Nogales et al., 1998). Each of these alleles was used to replace one of the copies of TUB2 in a diploid yeast strain (Reijo et al., 1994). The diploids were then sporulated to obtain haploid segregants. Seven of the haploid strains containing only the mutated allele of TUB2 were viable (Table I). Four of these displayed altered sensitivity to the microtubule-destabilizing drug benomyl, but only one, tub2-V169A, showed a substantial change in microtubule dynamics.

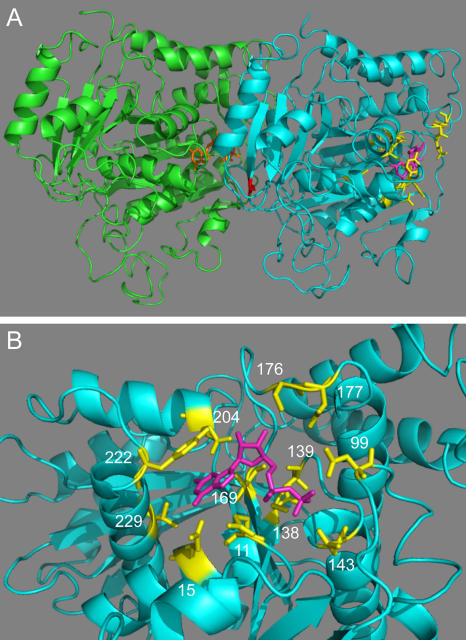

Figure 1.

Location of altered residues. (A) The structures of yeast Tub1 and Tub2 are homology models based on the structure of the αβ-tubulin heterodimer from bovine brain obtained by electron crystallography (Nogales et al., 1998; Richards et al., 2000). The C termini of Tub1 (residues 442–447) and Tub2 (residues 428–457) were not included in the model because they are not resolved in the bovine structure. Tub1, green; Tub2, cyan; GTP bound to Tub1, orange; GDP bound to Tub2, magenta; Tub2 residues changed to alanine in this study, yellow; Tub2-C354, red. (B) The GTP-binding pocket of Tub2. Coloring as in A. Numbers indicate positions of the mutated residues.

Table I.

Summary of tub2 mutants

| Amino acid substitution |

GTP contact | Viability | Benomyl sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | NA | + | WT (20) |

| Q11A | Phosphate | + | SS (10) |

| Q15A | Base | + | SS (10) |

| N99A | Phosphate | + | WT (30) |

| S138A | Phosphate | + | R (60) |

| L139A | Phosphate | − | NA |

| T143A | Phosphate | − | NA |

| V169A | Ribose | + | R (50) |

| S176A | Ribose | − | NA |

| D177A | Ribose | + | ND |

| N204A | Base | − | NA |

| Y222A | Base | + | WT (20) |

| V229A | Base | − | NA |

WT (wild type), similar to TUB2 cells; SS, supersensitive; R, resistant; ND, not determined because of the poor growth of the strain; NA, not applicable. Numbers in parentheses indicate the highest concentrations of benomyl (micrograms/milliliter) that allow growth as determined in 10-μg/ml steps.

The dynamics of individual cytoplasmic microtubules were measured in live yeast cells expressing GFP-tagged Tub1, the major α-tubulin in yeast (Fig. 2 A and Table II). Microtubules in tub2-V169A cells spent the majority of their time in the paused state neither growing nor shrinking to any detectable degree (83% in G1 cells and 65% in preanaphase cells). In contrast, microtubules in TUB2 cells paused <10% of the time. In addition, rates of microtubule growth and shrinkage were two- to threefold lower in tub2-V169A cells. Overall, the tub2-V169A mutation reduced cytoplasmic microtubule dynamicity by 18- and 7-fold in G1 and preanaphase cells, respectively.

Figure 2.

tub2-V169A and -C354A mutations decrease cytoplasmic and kinetochore microtubule dynamics. Microtubules were observed in live cells expressing GFP-Tub1 (CUY1302, CUY1844, and CUY1845). (A) Plots were constructed from measurements of cytoplasmic microtubule length versus time. (B) Quantitation of fluorescence redistribution of photobleached half spindles. Each point represents a mean value ± SEM (error bars). Curves were modeled from data as described previously (Wolyniak et al., 2006). (C) Values for the number of FRAP experiments (n) and for t1/2 and the extent of redistribution.

Table II.

Cytoplasmic microtubule dynamics

| Cells | Growth rate | Shrinkage rate | Rescue frequency |

Catastrophe frequency |

Pause time | Dynamicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm/min | μm/min | events/s | events/s | % | dimers/s | |

| G1 | ||||||

| TUB2 | 1.41 ± 0.42 | 2.55 ± 0.76 | 0.0051 | 0.0074 | 8 | 40.9 |

| tub2-V169A | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.36 | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | 83 | 2.3 |

| tub2-C354A | 0.63 ± 0.55 | 0.59 ± 0.26 | 0.0010 | 0.0015 | 79 | 2.8 |

| Preanaphase | ||||||

| TUB2 | 1.43 ± 0.68 | 1.78 ± 0.69 | 0.0063 | 0.0069 | 5 | 33.8 |

| tub2-V169A | 0.57 ± 0.24 | 0.75 ± 0.25 | 0.0017 | 0.0015 | 65 | 4.6 |

| tub2-C354A | 0.75 ± 0.74 | 0.98 ± 0.76 | 0.0010 | 0.0012 | 74 | 3.7 |

TUB2 (CUY1302): G1, n = 17 and t = 4,330 s; preanaphase, n = 10 and t = 4,070 s. tub2-V169A (CUY1844): G1, n = 8 and t = 4,500 s; preanaphase, n = 11 and t = 6,480 s. tub2-C354A (CUY1845): G1, n = 6 and t = 4,040 s; preanaphase, n = 7 and t = 4,200 s. n, number of time-lapse sequences; t, total length of time-lapse sequences obtained. Event rates are mean values ± SD.

Because individual kinetochore microtubules cannot be visualized in yeast by fluorescence microscopy, we used FRAP to assess their dynamics (Maddox et al., 2000). Half of a preanaphase spindle labeled with GFP-Tub1 was selectively photobleached. Then, the fluorescence intensities of both the bleached and unbleached half spindles were measured over time. From these values, we calculated the extent of redistribution and a time to half-maximal redistribution (t1/2), assuming that redistribution was caused by a first-order kinetic exchange of fluorescent molecules between the two half spindles. In TUB2 cells, ∼90% of the fluorescence redistributes with a t1/2 of 48 s (Fig. 2, B and C). In tub2-V169A cells, only ∼40% of the fluorescence redistributes with a t1/2 of 109 s. Thus, the tub2-V169A mutation severely decreases the dynamics of kinetochore microtubules.

The structure of yeast tubulin has been derived as a homology model from the solved structure of bovine brain tubulin (Richards et al., 2000). V169 of yeast β-tubulin is predicted to contact the ribose moiety of bound GDP (Fig. 1). We hypothesize that the V169A mutation lowers microtubule dynamics by altering the binding and/or hydrolysis of GTP. Another mutation in TUB2, tub2-C354A, has also been reported to severely decrease microtubule dynamics (Gupta et al., 2002). C354 is located at the intradimer contacts (Nogales et al., 1999) and may affect interactions within or between protofilaments (Fig. 1 A). We measured the effect of the tub2-C354A mutation on microtubule dynamics in our strain background. The results confirmed that this mutation leads to dramatic decreases in cytoplasmic and kinetochore microtubule dynamics that are similar to the effects of tub2-V169A (Table II and Fig. 2). Any differences between our results and those previously reported for tub2-C354A (Gupta et al., 2002) are likely the result of variations in strain background and methods of measurement. We decided to use both tub2-V169A and -C354A to characterize the roles of microtubule dynamics in mitosis. Given that these mutations likely work through different mechanisms, we should be able to attribute any common phenotypes to their similar effects on microtubule dynamics.

tub2-V169A and -C354A cells contain monopolar chromosomes

Both tub2-V169A and -C354A strains grow slowly: generation times are 280 and 220 min, respectively, versus 90 min for TUB2 cells. Cultures of tub2-V169A and -C354A cells contain ∼60% large-budded cells, and ∼60% of these contain an ∼1.5-μm preanaphase spindle. This high percentage of preanaphase cells is indicative of spindle assembly checkpoint activity that responds to defects in chromosome attachment to the mitotic spindle.

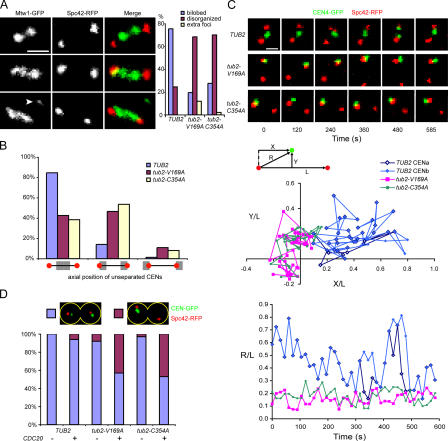

To examine chromosome attachment in tub2-V169A and -C354A cells, we visualized kinetochores using Mtw1-3GFP and spindle pole bodies (SPBs) using Spc42-RFP. In TUB2 preanaphase cells, sister chromatids are attached to microtubules originating from opposite poles, which is a configuration referred to as bipolar (amphitelic) attachment. Tension exerted by the microtubules pulls sister kinetochores and their associated centromeric DNA (centromere [CEN]) toward the two spindle poles (He et al., 2000). Thus, in >75% of preanaphase cells, Mtw1-GFP has a bilobed appearance with a region of staining adjacent to each spindle pole (Fig. 3 A, top). However, in tub2-V169A and -C354A mutants, only 20–30% of preanaphase cells show this bilobed Mtw1-GFP configuration. In ∼70% of these cells, Mtw1-GFP is distributed in a disorganized fashion along the spindle (Fig. 3 A, middle and bottom). In addition, a small percentage of the mutant cells have extra Mtw1-GFP foci located off the spindle and presumably denoting unattached kinetochores (Fig. 3 A, bottom). These results indicate that the mutants have difficulty establishing proper kinetochore attachments to the spindle.

Figure 3.

tub2-V169A and -C354A cells contain monopolar chromosomes. (A) Kinetochore localization in live cells expressing Mtw1-3GFP and Spc42-RFP (CUY1846, CUY1847, and CUY1848). Top, middle, and bottom panels show examples of Mtw1 localization as bilobed, disorganized, and disorganized with extra foci (arrowhead), respectively. Graph shows quantification of each category. (B and C) CEN4 localization in cells expressing CEN4-GFP and Spc42-RFP (CUY1849, CUY1850, and CUY1851). (B) Localization of unseparated CENs relative to SPBs in live cells. Categories are as follows: CENs closer to the middle of the spindle, CENs closer to SPBs, and CENs on the far side of SPBs. (C) Movement of CENs in live cells determined by time-lapse images taken at 15-s intervals for 10 min. Top panel shows images of z-series cells at the indicated time intervals. Videos 1–3 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb. 200606021/DC1) show the entire time course. Middle panel shows scatter plots of the position of CENs relative to the spindle over the 10-min time interval. CENa and CENb refer to the separated CEN4s in TUB2 cells. Bottom panel shows relative distance from CENs to the nearest SPB over the 10-min time interval. X, Y, L, and R are defined in the diagram. (D) CEN segregation at anaphase in the absence of the spindle assembly checkpoint. Cells expressing CEN4-GFP, Spc42-RFP, and Cdc20 from the GAL1 promoter (CUY1852, CUY1854, and CUY1856) and control cells expressing CEN4-GFP and Spc42-RFP but lacking PGAL1-CDC20 were grown in raffinose medium and transferred to galactose medium to induce Cdc20 for 3 h before imaging. Images show examples of correct (blue box) and incorrect (purple box) chromosome segregation. Bars, 1 μm.

To gain a more precise measure of kinetochore localization, we visualized a single CEN by integrating a LacO array 1.2 kb from CEN4 in cells expressing LacI-GFP. SPBs were visualized by expressing Spc42-RFP. 81% of TUB2 preanaphase cells contained two GFP dots representing the separation of sister CENs as a result of tension on the bioriented chromosomes. In contrast, 60% of the tub2-V169A cells and 56% of the tub2-C354A cells contained unseparated CENs, indicating monopolar attachment or bipolar attachment with a lack of tension. To distinguish between these possibilities, we examined the positions of unseparated CENs relative to the spindle. Monopolar CENs will remain close to the spindle pole to which they are attached, whereas bipolar CENs are more likely to reside in the middle of the spindle (Skibbens et al., 1993; He et al., 2001). In TUB2 cells, only 14% of unseparated CENs are located closer to one SPB than they are to the middle of the spindle (Fig. 3 B). In contrast, in 58% of tub2-V169A and 62% of tub2-C354A cells, unseparated CENs are located closer to one SPB. In each mutant, these numbers include ∼10% of unseparated CENs that reside on the far side of one SPB relative to the spindle, which is a position inconsistent with biorientation. Overall, using SPB proximal localization of unseparated CENs as a criterion for monopolar attachment, CEN4 has a monopolar attachment in 35% of preanaphase tub2-V169A and -C354A cells versus 3% of TUB2 cells.

Next, we examined the movement of unseparated CENs by time-lapse microscopy. In wild-type cells, CENs transiently separate as they oscillate along the spindle. However, ipl1 mutants, which form primarily monopolar (syntelic) attachments, contain unseparated CENs that remain close to one SPB (He et al., 2001). In contrast, in stu2 mutants, which form bipolar attachments lacking tension, unseparated CENs are found near the spindle midregion (He et al., 2001). As expected, we found that unseparated CENs in TUB2 cells moved back and forth along the spindle (Fig. 3 C). In 12/14 of the cases, CENs that were unseparated at the beginning of the recording separated, at least transiently, during the 10-min period of observation. Both the midspindle location and transient separation indicate bipolar attachment. In contrast, CEN separation was observed in only 4/15 tub2-V169A cells and 3/15 tub2-C354A cells during the 10-min periods of observation. In 6/11 tub2-V169A cells and 8/12 tub2-C354A cells that did not separate CENs, the unseparated CENs remained close to one SPB. Thus, time-lapse imaging indicates that 40 and 53% of the unseparated CENs in preanaphase tub2-C354A and -C354A cells, respectively, have a monopolar attachment.

An additional assay for monopolar attachment of chromosomes is to measure CEN segregation in the absence of the spindle assembly checkpoint. Normally, the presence of this checkpoint keeps cells with monopolar chromosomes from entering anaphase. In its absence, monopolar chromosomes will missegregate at anaphase. If both sister CENs are attached to one SPB (syntelic attachment), both will segregate with this SPB into one of the daughter cells. If only one of the sister CENs is attached to the SPB (monotelic attachment), random segregation of the unattached CEN will cause both CENs to segregate into one of the daughter cells about half of the time, although the unattached CEN would not likely reside near the SPB. On the other hand, bipolar attachment of CENs (amphitelic attachment), even the absence of tension, would not result in missegregation. We eliminated the spindle assembly checkpoint by the overexpression of Cdc20 from the GAL1 promoter (Schott and Hoyt, 1998). After 3 h of induction with galactose, sister CEN segregation was examined in anaphase cells. In 94% of TUB2 anaphase cells, sister CENs segregated correctly into the two daughter cells (Fig. 3 D). In tub2-V169A and -C354A cells, sister CENs segregated correctly in only 57 and 53% of cells, respectively. In all cases of missegregation, both CENs were located close to the SPB, suggesting syntelic attachment.

In summary, the examination of CEN4 position and movement indicates that at least 25% of the tub2-V169A and -C354A preanaphase cells contain monopolar attachments. Assuming that each of the 16 yeast CENs behaves similarly to CEN4, each preanaphase cell contains on average four monopolar attached chromosomes. Although the tub2 mutants biorient chromosomes much less efficiently than TUB2 cells, these cells are viable because the spindle assembly checkpoint holds them in mitosis until the biorientation of all chromosomes has been achieved. Thus, preanaphase cells in asynchronously growing tub2 cultures represent a mixed population; those that have been arrested in mitosis the longest will likely contain the fewest monopolar chromosomes. As expected, in the absence of the checkpoint, these cells missegregate chromosomes at a high rate. Assuming that chromosome IV is representative, about half of the 16 yeast chromosomes missegregate in each mitosis.

Rates of chromosome capture and biorientation are decreased in tub2-V169A and -C354A cells

To assess the rate of biorientation, we arrested cells at the start of the cell cycle with α factor and then allowed them to proceed synchronously into mitosis. The cells were held in metaphase by blocking the transcription of CDC20 at the time of release from α factor. The CDC20 gene was under the control of the MET3 promoter, allowing it to be shut off by the addition of methionine. These strains also contained GFP-labeled CEN3 (in this case, a TetO array was integrated near CEN3 in cells expressing TetR-GFP) and YFP-Tub1. The cells formed preanaphase spindles ∼50 min after release from α factor. At this time, >75% of the TUB2 preanaphase spindles contained bioriented chromosomes, as indicated by the separation of CEN dots (Fig. 4 A). This value remained relatively constant over the next 90 min. In tub2-V169A and -C354A cells, only 21 and 15% of the preanaphase cells, respectively, contained separated CENs at the 50-min time point. This value increased steadily over the next 50 min but leveled off at ∼55% after 100 min.

Figure 4.

Chromosome capture and biorientation are inhibited in tub2-V169A and -C354A cells. (A–C) Cells contain YFP-Tub1, PGAL1-CEN3-GFP, and PMET3-CDC20 (T3531, CUY1858, and CUY1859). (A) Cells were treated with α factor for 3 h in medium containing glucose and lacking methionine and were shifted to medium lacking α factor and containing glucose and 2 mM methionine. Aliquots of cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde at 10-min time intervals for imaging. Images show cells with unseparated and separated CENs associated with preanaphase spindles. (B) Cells were treated with α factor for 3 h in medium containing raffinose and lacking methionine and were shifted to medium containing galactose and 2 mM methionine. After 3 h, cells were transferred to medium containing glucose and 2 mM methionine (defined as t = 0). Aliquots of cells were fixed at the indicated times. The percentage of cells with free CEN3, CEN3 on a captured microtubule, CEN3 on the spindle but not separated, and CEN3 on the spindle and separated was determined. The ratio of separated to unseparated CENs on the spindle versus time is shown in the bottom graph. (C) Images of live cells subjected to the procedure described in B were captured at 30-s intervals. The zero time point is defined as the time when the captured CEN reaches the spindle. Top panel shows a TUB2 cell in which the CENs separated 210 s after reaching the SPB. Middle panel shows a tub2-V169A cell in which CENs separated 540 s after reaching the SPB. Bottom panel shows a tub2-C354A cell in which the CENs did not separate within 900 s after reaching the SPB. (A and C) Arrowheads indicate CEN-GFP dots. Videos 4–6 (available at http://www.jcb.org/ cgi/content/full/jcb.200606021/DC1) show the entire time course for these cells. Bars, 1 μm.

To examine chromosome capture and biorientation directly, we used a system developed by Tanaka et al. (2005). In this system, the GAL1 promoter is placed adjacent to CEN3. Transcription through the CEN interferes with kinetochore assembly; thus, CEN3 can be conditionally activated or inactivated by switching between media containing glucose and galactose. This CEN3 is also marked by TetO/TetR-GFP. The cells again have the CDC20 gene under the control of the MET3 promoter and express Tub1-YFP. To visualize the capture of CEN3 by an individual microtubule, cells were synchronized with α factor and released into medium containing methionine and galactose for 3 h. This caused cells to arrest in metaphase with inactivated CEN3 generally located away from the spindle. The cells were then switched to glucose medium to reactivate CEN3. The kinetics of CEN3 capture and biorientation were determined by fixing aliquots of cells at different time points and determining the fraction of cells with free CEN3, CEN3 on a captured microtubule, CEN3 on the spindle but not separated, and CEN3 on the spindle and separated. In TUB2 cells, CEN3 was captured in ∼90% of the cells within 10 min of its reactivation (Fig. 4 B). In contrast, CEN3 was captured in <50% of tub2-V169A and -C354A cells in 10 min. Even after 60 min, 24 and 18% of the tub2-V169A and -C354A cells, respectively, contained free CEN3. In addition, captured CENs became bioriented much more slowly in the tub2 mutants. For TUB2 cells, the ratio of separated to unseparated spindle-associated CENs increased steadily to ∼4.5 in 40 min (Fig. 4 B, bottom). At the same time, this value was 1.1 for tub2-V169A cells and 1.2 for tub2-C354 cells.

Finally, we used live cell imaging to measure the time between the arrival of CEN3 on the spindle and biorientation as indicated by its separation into two dots along the spindle (Fig. 4 C). In TUB2 cells, this time interval was 163 ± 98 s (n = 14). For 9/12 tub2-V169A cells observed, the time interval for CEN separation was 533 ± 275 s. In the other three cells, CENs failed to separate within periods of observation averaging 1,030 s. For 6/10 tub2-C354A cells observed, the time interval for CEN separation was 725 ± 302 s. In the other four cells, CENs failed to separate during a mean period of observation of 900 s.

The slow rates of initial CEN capture in this experiment might appear to be at odds with our aforementioned results indicating that most CENs in the tub2 mutants are attached to at least one SPB. However, S. cerevisiae kinetochores likely maintain microtubule attachments throughout the cell cycle, eliminating the need for their initial capture early in mitosis (Winey and O'Toole, 2001; Tanaka et al., 2002). On the other hand, the slow rates of CEN separation agree with the low percentage of bioriented chromosomes in growing cultures of these mutant strains.

In summary, two mutations in the yeast β-tubulin gene that attenuate kinetochore microtubule dynamics greatly decrease the probability of chromosome capture and biorientation. These results demonstrate that microtubule search and capture plays a central role in the assembly of the yeast mitotic spindle.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table III. tub2 alleles were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using overlapping PCR (Eichinger et al., 1996) and were integrated into yeast as described previously (Reijo et al., 1994). All other constructs were made by plasmid integration or the one-step PCR method for gene modification (Longtine et al., 1998). Mtw1-GFP was a gift from S. Biggins (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA).

Table III.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CUY25 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 | Huffaker laboratory |

| CUY1842 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 | This study |

| CUY1843 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 | This study |

| CUY1302 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 ura3-52∷PTUB1-GFP-TUB1∷URA3 | Huffaker laboratory |

| CUY1844 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 TUB1∷HIS3∷PTUB1-GFP-TUB1 | This study |

| CUY1845 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 TUB1∷HIS3∷PTUB1-GFP-TUB1 | This study |

| CUY1846 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 MTW1-3GFP∷HIS3 SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1847 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 MTW1-3GFP∷HIS3 SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1848 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 MTW1-3GFP∷HIS3 SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1849 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 CEN4∷lacO256∷NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1850 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1851 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 | This study |

| CUY1852 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 CEN4∷lacO256∷NAT SPC42-RFP∷ KanMX6 (pBH38: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-3xHA) | This study |

| CUY1853 | MATa ade2 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 CEN4∷lacO256∷NAT SPC42-RFP∷ KanMX6 (pBH39: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-CDC20-3xHA) | This study |

| CUY1854 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 (pBH38: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-3xHA) | This study |

| CUY1855 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-V169A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 (pBH39: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-CDC20-3xHA) | This study |

| CUY1856 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT SPC42-RFP∷KanMX6 (pBH38: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-3xHA) | This study |

| CUY1857 | MATa ade2-101 his3-Δ200∷lacI-GFP∷HIS3 leu2-Δ1 ura3-52 tub2-C354A∷URA3 CEN4∷lacO256∷ NAT Spc42-RFP∷KanMX6 (pBH39: YEp ampR LEU2 PGAL1-CDC20-3xHA) | This study |

| T3531 | MATa ade2 his3-11,15 PGAL1-CEN3-tetO112∷URA leu2∷TetR-GFP∷LEU2 trp1∷YFP-TUB1∷TRP PMET3-CDC20∷TRP1 | T. Tanakaa |

| CUY1858 | MATa ade2 his3-11,15 PGAL1-CEN3-tetO112∷URA leu2∷TetR-GFP∷LEU2 trp1∷YFP-TUB1∷TRP PMET3-CDC20∷ TRP1 tub2-V169A∷HIS3 | This study |

| CUY1859 | MATa ade2 his3-11,15 PGAL1-CEN3-tetO112∷URA leu2∷TetR-GFP∷LEU2 trp1∷YFP-TUB1∷TRP PMET3-CDC20∷ TRP1 tub2-C354A∷HIS3 | This study |

University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Microscopy and image analysis

Images that did not involve time-lapse microscopy were obtained with a microscope (Axioplan 2; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) equipped with a 100× plan-Apo NA 1.4 objective, camera (CoolSNAP fx; Photometrics), and Openlab software (Improvision). All images were captured using 2 × 2 binning except those in Fig. 3 A, which were not binned. Time-lapse studies in Figs. 2 A and 3 C were obtained with a spinning disk confocal imaging system (PerkinElmer) equipped with a microscope (TE2000; Nikon), a 100× plan-Apo NA 1.4 objective, camera (Orca ER; Hamamatsu), and UltraVIEW software (PerkinElmer) using 2 × 2 binning. Time-lapse images in Fig. 4 C were obtained using a confocal microscope system (TCS SP2; Leica) with a 100× plan-Apo NA 1.4 objective. The excitation wavelength was 488 nm; the GFP signal was collected at 493–518 nm, and the YFP signal was collected at 527–607 nm. All images were obtained at room temperature and are maximum intensity projections of z-series stacks (Δz = 0.5 μm). Linear contrast enhancement was performed using Photoshop CS (Adobe). Analysis of cytoplasmic microtubule dynamics (Kosco et al., 2001) and FRAP of spindle microtubules (Wolyniak et al., 2006) were performed as described previously. In the latter experiments, the extent of redistribution is defined as 1 − f.

Online supplemental material

Videos 1–3 show the movement of CENs in TUB2, tub2-V169A, and tub2-C354A yeast, respectively. Videos 4–6 show CEN capture and biorientation in TUB2, tub2-V169A, and tub2-C354A yeast cells, respectively. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200606021/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Carol Bayles for help with the confocal microscope, Sue Biggins for the Mtw1-GFP construct, Tomoyuki Tanaka for the yeast strain T3531, and Lynne Cassimeris and Beth Lalonde for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to T.C. Huffaker.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CEN, centromere; SPB, spindle pole body.

References

- Desai, A., and T.J. Mitchison. 1997. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:83–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger, L., L. Bomblies, J. Vandekerckhove, M. Schleicher, and J. Gettemans. 1996. A novel type of protein kinase phosphorylates actin in the actin-fragmin complex. EMBO J. 15:5547–5556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss, O.J., and I. Vernos. 2004. The mechanism of spindle assembly: functions of Ran and its target TPX2. J. Cell Biol. 166:949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.L., Jr., C.J. Bode, D.A. Thrower, C.G. Pearson, K.A. Suprenant, K.S. Bloom, and R.H. Himes. 2002. beta-Tubulin C354 mutations that severely decrease microtubule dynamics do not prevent nuclear migration in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:2919–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, J.H., S.S. Bowser, and C.L. Rieder. 1990. Kinetochores capture astral microtubules during chromosome attachment to the mitotic spindle direct visualization in live newt lung cells. J. Cell Biol. 111:1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., S. Asthana, and P.K. Sorger. 2000. Transient sister chromatid separation and elastic deformation of chromosomes during mitosis in budding yeast. Cell. 101:763–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., D.R. Rines, C.W. Espelin, and P.K. Sorger. 2001. Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. Cell. 106:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holy, T.E., and S. Leibler. 1994. Dynamic instability of microtubules as an efficient way to search in space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:5682–5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, T.M., M.A. Lampson, P. Hergert, L. Cameron, D. Cimini, E.D. Salmon, B.F. McEwen, and A. Khodjakov. 2006. Chromosomes can congress to the metaphase plate before biorientation. Science. 311:388–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, M., and T. Mitchison. 1986. Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis. Cell. 45:329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosco, K.A., C.G. Pearson, P.S. Maddox, P.J. Wang, I.R. Adams, E.D. Salmon, K. Bloom, and T.C. Huffaker. 2001. Control of microtubule dynamics by Stu2p is essential for spindle orientation and metaphase chromosome alignment in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:2870–2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., A. McKenzie III, D.J. Demarini, N.G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J.R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, P.S., K.S. Bloom, and E.D. Salmon. 2000. The polarity and dynamics of microtubule assembly in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, E., S.G. Wolf, and K.H. Downing. 1998. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature. 391:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, E., M. Whittaker, R.A. Milligan, and K.H. Downing. 1999. High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell. 96:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijo, R.A., E.M. Cooper, G.J. Beagle, and T.C. Huffaker. 1994. Systematic mutational analysis of the yeast b-tubulin gene. Mol. Biol. Cell. 5:29–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, K.L., K.R. Anders, E. Nogales, K. Schwartz, K.H. Downing, and D. Botstein. 2000. Structure-function relationships in yeast tubulins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:1887–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott, E.J., and M.A. Hoyt. 1998. Dominant alleles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC20 reveal its role in promoting anaphase. Genetics. 148:599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbens, R.V., V.P. Skeen, and E.D. Salmon. 1993. Directional instability of kinetochore motility during chromosome congression and segregation in mitotic newt lung cells: a push-pull mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 122:859–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.U., N. Rachidi, C. Janke, G. Pereira, M. Galova, E. Schiebel, M.J. Stark, and K. Nasmyth. 2002. Evidence that the Ipl1-Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell. 108:317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K., N. Mukae, H. Dewar, M. van Breugel, E.K. James, A.R. Prescott, C. Antony, and T.U. Tanaka. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of kinetochore capture by spindle microtubules. Nature. 434:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey, M., and E.T. O'Toole. 2001. The spindle cycle in budding yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:E23–E27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollman, R., E.N. Cytrynbaum, J.T. Jones, T. Meyer, J.M. Scholey, and A. Mogilner. 2005. Efficient chromosome capture requires a bias in the ‘search-and-capture’ process during mitotic-spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 15:828–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolyniak, M.J., K. Blake-Hodek, K. Kosco, E. Hwang, L. You, and T.C. Huffaker. 2006. The regulation of microtubule dynamics in S. cerevisiae by three interacting plus-end tracking proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:2789–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. 2004. G protein control of microtubule assembly. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:867–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.