Abstract

Organ homeostasis and organismal survival are related to the ability of stem cells to sustain tissue regeneration. As a consequence of accelerated telomerase shortening, telomerase-deficient mice show defective tissue regeneration and premature death. This suggests a direct impact of telomere length and telomerase activity on stem cell biology. We recently found that short telomeres impair the ability of epidermal stem cells to mobilize out of the hair follicle (HF) niche, resulting in impaired skin and hair growth and in the suppression of epidermal stem cell proliferative capacity in vitro. Here, we demonstrate that telomerase reintroduction in mice with critically short telomeres is sufficient to correct epidermal HF stem cell defects. Additionally, telomerase reintroduction into these mice results in a normal life span by preventing degenerative pathologies in the absence of increased tumorigenesis.

Introduction

Telomeres, which are composed of tandem repeats of the TTAGGG sequence and associated proteins, are nucleoprotein structures that cap the ends of chromosomes (for reviews see Blackburn, 2001; Chan and Blackburn, 2002; de Lange, 2005). Telomere length is maintained by telomerase, a reverse transcriptase that counteracts telomere shortening associated with cell division by de novo addition of telomere repeats onto chromosome ends (for review see Chan and Blackburn, 2002). Telomerase is expressed in the stem cell compartment of several adult tissues, where it is thought to compensate for telomere shortening associated with cell proliferation and tissue regeneration (for reviews see Collins and Mitchell, 2002; Harrington, 2004; Flores et al., 2005, 2006; Sarin et al., 2005). Interestingly, telomerase activity levels are not sufficient to maintain telomere length during human aging, and telomeres progressively shorten with increasing age in the context of the organism (Harley et al., 1990; Canela et al., 2007; for review see Blasco, 2005) and are also associated with different disease states (Samani et al., 2001; Wiemann et al., 2002; Cawthon et al., 2003; Epel et al., 2004; Valdes et al., 2005). Indeed, telomerase levels in humans and mice are thought to be rate limiting for organismal life span. In particular, reduced telomerase activity caused by mutations in telomerase components in the human diseases dyskeratosis congenita (Mitchell et al., 1999; Vulliamy et al., 2001, 2004; Mason et al., 2005), aplastic anemia (Marrone et al., 2004; Yamaguchi et al., 2005), and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Armanios et al., 2007; Tsakiri et al., 2007) leads to accelerated telomere shortening, premature loss of tissue regeneration, and premature death. Some of these phenotypes are shared by telomerase-deficient mice (Terc −/− mice; Blasco et al., 1997), which show a reduction in both the median and the maximum life span already within the first mouse generation (García-Cao et al., 2006). Furthermore, these defects are anticipated with subsequent Terc −/− mouse generations with progressively shorter telomeres concomitant with premature loss of tissue regeneration and organismal survival (Lee et al., 1998; Herrera et al., 1999; Leri et al., 2003; Flores et al., 2005; García-Cao et al., 2006). Similarly, disease anticipation has also been reported with increasing generations of human dyskeratosis congenita patients (Vulliamy et al., 2004).

The telomerase-deficient mouse model has been instrumental in understanding the effects of telomere shortening on stem cell biology (for review see Blasco, 2005). In particular, we recently showed that telomere shortening results in an impaired capacity of hair follicle (HF) stem cells to regenerate the hair and the skin because of a defective mobilization of the HF stem cells out of their niche (Flores et al., 2005). This defective stem cell behavior anticipates the fact that telomerase-deficient mice show premature skin-aging phenotypes such as decreased wound healing, hair loss, and hair graying (Lee et al., 1998; Herrera et al., 1999; Rudolph et al., 1999), as well as decreased skin cancer, as indicated by the fact that they are resistant to skin carcinogenesis protocols (Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2000). These findings suggested that the progressive telomere shortening that occurs in human tissues with increasing age might directly impact the ability of different adult stem cell populations to maintain tissue homeostasis. Furthermore, these results opened the possibility that restoration of telomerase activity may be sufficient to correct stem cell defects associated with short telomeres and to extend the organismal life span.

Here, we demonstrate that restoration of a copy of the Terc gene into late generation G3/G4 telomerase-deficient mice is sufficient to elongate critically short telomeres in skin keratinocytes from these mice, prevent end-to-end chromosome fusions, and rescue both HF stem cell defects in vivo and the impaired proliferative capacity of epidermal stem cells ex vivo. Finally, telomerase reintroduction was able to extend the normal life span of G4 telomerase-deficient mice by preventing degenerative pathologies in the absence of increased cancer. These findings support the notion that telomerase activators would be sufficient to correct stem cell defects in tissues with critically short telomeres in the absence of undesired effects.

Results

Reintroduction of the telomerase Terc gene in late generation Terc-deficient mice is sufficient to elongate critically short telomeres and prevent chromosomal instability in skin keratinocytes

To test whether telomerase reintroduction was able to elongate short telomeres in skin keratinocytes from late generation G3/G4 Terc-deficient mice, we first generated large colonies of littermate mice from Terc +/− × G2/G3 Terc −/− intercrosses (Materials and methods). The progeny of these crosses was divided into two mouse cohorts according to their telomerase status: G3/G4 Terc −/− telomerase-deficient mice and G3/G4 Terc +/− telomerase-reconstituted mice (referred to here as G3/G4 Terc +/−* mice). Importantly, both mouse cohorts inherited the same telomere length from the parents; however, G3/G4 Terc −/− mice lack telomerase activity and G3/G4 Terc +/−* mice are telomerase proficient (Fig. 1). To address whether telomerase activity in G3 Terc +/−* mice was able to rescue short telomeres compared with G3 Terc −/− cohorts, we measured telomere length using quantitative FISH (Q-FISH) on primary keratinocytes obtained from newborn mice (Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2000; Muñoz et al., 2005; Materials and methods). G3 Terc +/−* skin keratinocytes showed, on average, longer telomeres than those from the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P < 0.001; Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, this telomere elongation coincided with a significant reduction of the percentage of short telomeres (<100 arbitrary units of fluorescence [a.u.f.]) in G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P < 0.001; Fig. 2, A and B), which is in agreement with previous findings showing that telomerase preferentially elongates short telomeres both in yeast and mammals (Hemann et al., 2001; Samper et al., 2001; Teixeira et al., 2004). The percentage of longest telomeres (>1,000 a.u.f.) was also significantly increased in telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P = 0.015; Fig. 2, A and B), in agreement with the increase in mean telomere length.

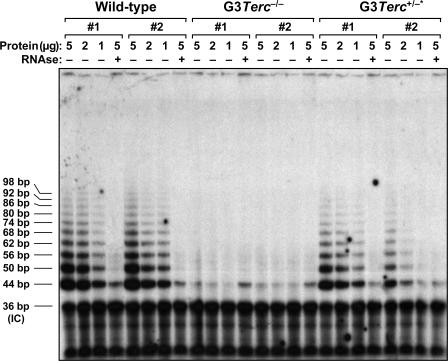

Figure 1.

Reconstitution of telomerase activity in G3 Terc+/−* mice compared with their G3 Terc−/− siblings. Telomerase is successfully reconstituted in two independent MEF cultures from G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with their telomerase-deficient G3 Terc −/− littermates. Two wild-type MEFs are also included as a positive control for telomerase activity. The protein concentration used is indicated on top of each lane. Extracts were treated (+) or not treated (−) with RNase as a negative control. An internal control (IC) for PCR efficiency was also included.

Figure 2.

Rescue of mean telomere length and percentage of short telomeres in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* keratinocytes. (A) Telomere length histogram obtained by Q-FISH in primary murine skin keratinocytes. The histogram shown is representative of three independent pairs of G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* littermates (see B). Note a greater abundance of short telomeres in the G3 Terc −/− mouse compared with the G3 Terc +/−* littermate. Red lines facilitate visualization of short (<100 a.u.f.) and long (>1,000 a.u.f.) telomeres. The total number of telomere dots used for the quantification and the percentage of short and long telomeres are indicated. (B) Mean telomere length is significantly increased (P < 0.001) in G3 Terc +/−* compared with G3 Terc −/− mice. Concomitantly, these mice show a significant (P < 0.001) decrease in the percentage of short telomeres and a significant (P = 0.015) increase in the percentage of long telomeres. Data are mean values ± SEM for three independent pairs of G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* littermates.

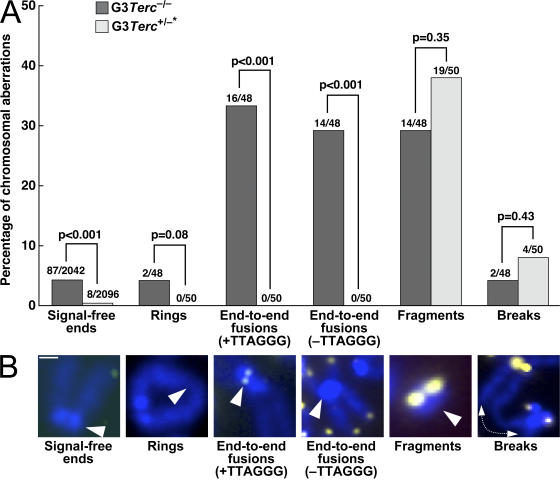

Finally, we determined whether the elongated telomeres in G3 Terc +/−* keratinocytes correlated with a significant rescue of chromosomal aberrations associated with critically short telomeres. For this, we performed a full karyotypic analysis using telomere Q-FISH on metaphases (Materials and methods). As shown in Fig. 3 (A and B), telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* keratinocytes showed a significant rescue of chromosomal abnormalities associated with critically short telomeres, such as signal-free ends and end-to-end fusions, compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− controls (P < 0.001 for all comparisons), suggesting that these types of aberrations are the direct consequence of critical telomere shortening and that when short telomeres are reelongated by telomerase they are completely prevented. In contrast, breaks and fragments are not rescued by telomerase reintroduction, indicating that they are not the direct consequence of critical telomere shortening.

Figure 3.

Significant rescue of signal-free ends and end-to-end chromosomal fusions in G3 Terc+/−* keratinocytes. (A) Quantification of the frequency of the indicated chromosomal aberrations in primary keratinocytes from G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* mice. The total number of chromosomes scored for the analysis is indicated on top of each bar. Statistical comparisons using the χ2 test are shown. (B) Representative examples of the indicated chromosomal aberrations are shown below the graph. Note that signal-free ends and end-to-end fusions are significantly rescued in Terc-reconstituted G3 mice compared with the G3 Terc-deficient littermates, which is in agreement with the fact that telomerase elongates short telomeres, thus preventing telomere dysfunction. Bar, 0.4 μm.

Reintroduction of the telomerase Terc gene into G3/G4 Terc-deficient mice is sufficient to rescue mobilization defects of epidermal HF stem cells

To investigate whether elongation of short telomeres by telomerase in skin keratinocytes was sufficient to rescue epidermal stem cell defects in late generation telomerase-deficient mice (Flores et al., 2005), we compared the number and mobilization ability of epidermal stem cells in the HF stem cell niche before and after mitogenic activation in G3 Terc +/−* mice with that of the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (Fig. 4, A–C). To visualize HF stem cells, we used a labeling technique previously shown to mark self-renewing and multipotent epidermal cells, the so-called label retaining cells (LRCs; for review see Fuchs et al., 2004; Flores et al., 2005; Moore and Lemischka, 2006). Of notice, these experiments were performed in young mice (0–2 mo old) from both genotypes before any skin phenotypes associated with short telomeres were detectable. Confocal microscopy revealed that LRCs are enriched at the bulge area of the HF in the two genotypes, which is in agreement with the known location of the HF stem cell niche (Fig. 4 C; Cotsarelis et al., 1990; Oshima et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2004; Tumbar et al., 2004).

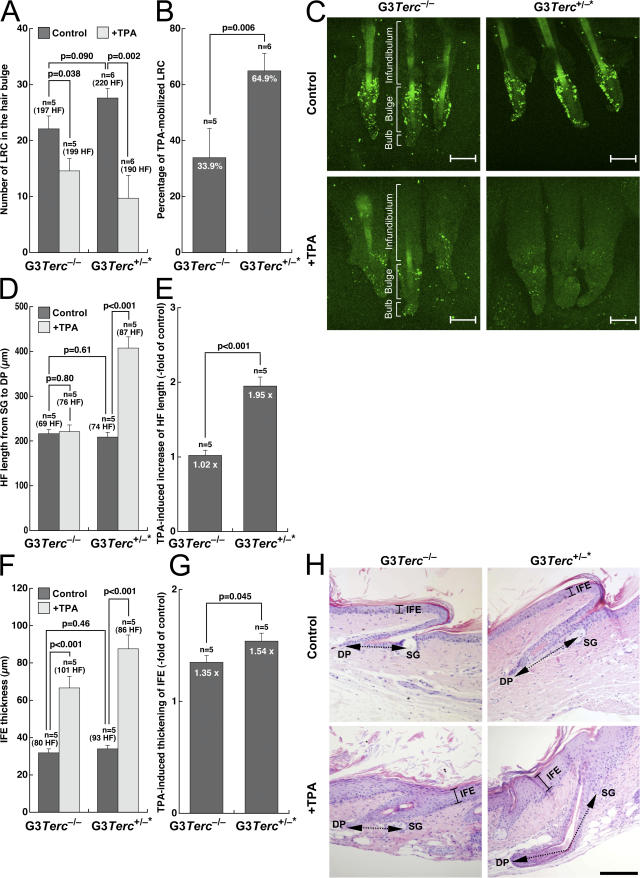

Figure 4.

Rescue of HF stem cell mobilization defects, as well as of skin and hair growth defects in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* mice upon TPA treatment. (A and B) To assay mobilization of LRCs, mice of the indicated genotype were injected with BrdU and after 69 d, whole mounts of tail epidermis were collected from untreated and TPA-treated mice and stained with a BrdU antibody. The number of LRCs at the hair bulge in resting conditions or after stimulation with TPA in littermate G3 Terc +/−* and G3 Terc −/− mice are indicated (A). LRC numbers were calculated in at least five mice of each genotype (n), quantifying at least 197 follicles in the control group and at least 190 follicles in the TPA-treated group (A). Note a higher percentage of mobilization of LRCs in TPA-treated G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 Terc −/− mice (B). (C) Representative confocal micrographs of tail follicles from G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* mice were stained for BrdU (green) before (controls) and after (+TPA) TPA treatment. LRCs of all genotypes accumulate in the bulge (Bu) region of the HF. Bar, 80 μm. Note a greater disappearance of LRCs in Terc +/−* TPA-treated HFs compared with the G3 Terc −/− littermates. The different compartments (infundibulum, hair bulge, and hair bulb) of the HF are indicated. (D–G) Quantification of HF length from sebaceous glands (SG) to dermal papilla (DP; D and E) and of IFE thickness (F and G) in tail skin from mice of the indicated genotype. Histomorphometry was performed in five mice of each genotype (n), quantifying at least 69 follicles in the control group and at least 76 follicles in the TPA-treated group. Note the increased HF length and IFE thickness in TPA-treated G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 Terc −/− littermates (P < 0.05 for both; E and G). (H) Representative tail skin sections from mice of the indicated genotypes before (control) and after (+TPA) TPA treatment. Bracketed continuous black lines mark IFE. Black dashed double-pointed arrows mark HF length from sebaceous glands to dermal papilla. Bar, 150 μm. Error bars in A, B, and D–G represent SEM.

In control resting skin conditions, we did not detect significant differences in the numbers of LRCs at the hair bulge of G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P = 0.090; Fig. 4, A and C). To test whether the hair bulge stem cells were able to mobilize (exit their quiescence state and migrate) out of the niche, we studied the response of G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* LRCs to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) treatment, a potent tumor promoter that activates LRCs to give numerous progeny (Flores et al., 2005). TPA treatment results in rapid disappearance of LRCs (Braun et al., 2003), skin hyperplasia (Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2000), and entry of HFs into their anagen (growing) phase (Wilson et al., 1994). After TPA treatment, only 34% of the LRCs mobilized out of the HF niche in G3 Terc −/− mice (Fig. 4, B and C) compared with the previously reported 70% mobilization in wild-type mice of different genetic backgrounds (Flores et al., 2005), thus confirming the defective stem cell mobilization associated with short telomeres. In contrast, 65% of LRCs mobilized in TPA-treated G3 Terc +/−* mice (P = 0.006; Fig. 4 B). A similar rescue in HF stem cell mobilization defects was obtained when comparing G4 Terc +/−* mice to the corresponding G4 Terc −/− littermates (Fig. S1, A–C, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704141/DC1). Collectively, these results demonstrate that telomerase reintroduction in late generation G3 and G4 Terc +/−* mice significantly rescues epidermal HF stem cell mobilization defects compared with the G3 and G4 Terc −/− littermates.

In agreement with the defects in HF stem cell mobilization associated with short telomeres, HF length was not significantly increased in G3 Terc −/− mice after TPA treatment (P = 0.80; Fig. 4, D, E, and H), reflecting a defective HF anagen response in these mice after TPA treatment (Flores et al., 2005). Again, telomerase reintroduction rescued this defect in G3 Terc +/−* littermates, where HF length was significantly increased in response to TPA treatment compared with resting nontreated skin (P < 0.001; Fig. 4, D, E, and H), suggesting that telomerase is sufficient to restitute skin homeostasis in these mice. Similar results were obtained for increased interfollicular epidermis (IFE) thickness in response to TPA treatment. Again, telomerase reintroduction in G3 Terc +/−* littermates resulted in increased IFE hyperplasia compared with littermate G3 Terc −/− mice in response to TPA treatment (P < 0.05; Fig. 4, F–H). To study whether the increased IFE hyperplasia in G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with the G3 Terc −/− controls was associated with significant differences in cell proliferation or apoptosis, we performed immunohistochemistry of skin sections with antibodies against Ki67 and caspase 3 to detect proliferating and apoptotic cells, respectively (Materials and methods). As shown in Fig. S2 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704141/DC1), we did not detect considerable differences in the percentage of Ki67-positive cells between G3 Terc +/−* and G3 Terc −/− either in resting skin conditions or upon TPA treatment. Similarly, we were unable to detect caspase 3–positive cells in the skin of G3 Terc +/−* and G3 Terc −/− mice, suggesting that apoptosis is not a major cellular response to critically short telomeres in the skin (Fig. S3). Finally, we studied whether there were differences in skin differentiation markers between G3 Terc +/−* and G3 Terc −/− mice by performing immunohistochemistry with antibodies against K14 and p63, two skin basal-layer markers whose expression is normally reduced at the suprabasal skin layers (Materials and methods). We could not detect significant differences in the percentage of cells or in the number of keratinocyte layers positive for these markers (Figs. S4 and S5).

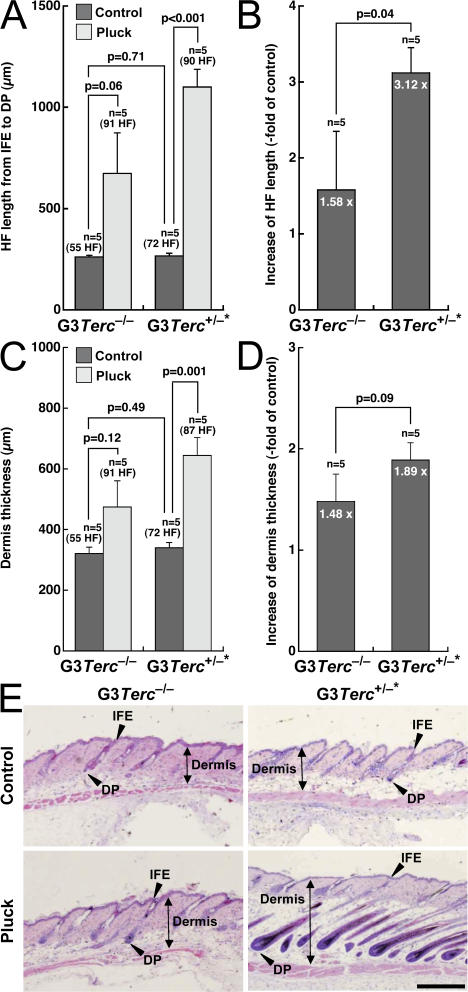

Next, we used hair-plucking experiments as an independent way to induce entry of HFs into their anagen phase (Flores et al., 2005; Materials and methods). In control resting skin conditions, we did not detect differences in back skin HF length and dermis thickness between G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* littermates (P = 0.71 and P = 0.49, respectively; Fig. 5, A, C, and E). Upon hair plucking, however, G3 Terc +/−* mice showed a significantly increased back skin HF length and dermis thickness compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P = 0.04 and P = 0.09, respectively; Fig. 5, A–E), again demonstrating that telomerase reintroduction in mice with short telomeres is able to improve the ability of epidermal HF stem cells to mobilize and regenerate the hair and skin.

Figure 5.

Rescue of skin and hair growth defects in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* mice upon hair plucking of back skin. (A–D) Quantification of HF length from IFE to dermal papilla (A and B) and of dermis thickness (C and D) in back skin from mice of the indicated genotype. Histomorphometry was performed in five mice of each genotype, quantifying at least 55 follicles in the control groups and at least 87 follicles in the TPA-treated groups. Note the increased HF length and dermis thickness in G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 Terc −/− littermates after plucking (B and D). Error bars represent SEM. (E) Representative back skin sections from mice of the indicated genotypes before (control) and after (pluck) plucking. Black double-pointed arrows mark dermis thickness. Arrowheads mark HF length from IFE to dermal papilla. Bar, 480 μm.

Rescue of proliferative potential of epidermal stem cells ex vivo in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* mice

It has been previously described that the epidermal stem cell defects observed in late generation telomerase-deficient mice are cell autonomous, as indicated by a defective clonogenic potential of these cells ex vivo (Flores et al., 2006). Individual colonies in clonogenic assays have been proposed to derive from single stem cells (Barrandon and Green, 1987; Materials and methods). Here, we performed clonogenic assays to compare the proliferation potential of telomerase-deficient G3 Terc −/− and telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* epidermal stem cells (Materials and methods). In agreement with the in vivo results shown in Fig. 4, primary keratinocytes from newborn G3 Terc −/− mice formed fewer and smaller colonies than those from wild-type controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 6, A and B), reflecting the previously described defective capacity of late generation Terc-null epidermal stem cells to proliferate ex vivo (Flores et al., 2005). Interestingly, the defective clonogenic potential of these cells was significantly corrected in telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* keratinocytes compared with the corresponding G3 Terc −/− controls (P = 0.006; Fig. 6, A and B), demonstrating that telomerase reintroduction ameliorates the ex vivo proliferative capacity of epidermal stem cells from late generation telomerase-deficient mice.

Figure 6.

Rescue of proliferative potential of epidermal stem cells ex vivo and of small body-size phenotype in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* mice. (A) Representative images of number and size of macroscopic colonies obtained from isolated keratinocytes of the indicated genotypes. Note more abundant and larger colonies in G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 Terc −/− littermates. (B) Quantification of size and number of macroscopic colonies obtained from isolated keratinocytes of the indicated genotype purified from 2-d-old mice and cultured for 10 d on J2-3T3 mitomycin C–treated feeder fibroblasts. (C) Representative images of newborn (left) and 2-mo-old (right) mice of the indicated genotype. Note a small body size in G3 Terc −/− mice compared with wild-type controls and that this small body-size phenotype is largely rescued in telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice. (D) Quantification of body weight in newborn (left) and 2-mo-old (right) mice of the indicated genotypes. Note significantly reduced body size in newborn G3 Terc −/− mice compared with both wild-type controls and telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice (P < 0.001 for both) and the significantly reduced body size in adult G3 Terc −/− mice compared with telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice (P < 0.001). Error bars in B and D represent SEM.

Reintroduction of the telomerase Terc gene in G3 Terc-deficient mice is sufficient to rescue their small body-size phenotype

We have previously described that late generation telomerase-deficient mice show a small body-size phenotype at the time of birth, which is associated with shorter telomeres in these mice as well as with a decreased clonogenic potential of epidermal stem cells in vitro (Flores et al., 2005). These observations opened the intriguing possibility that body size and stem cell proliferative potential may be mechanistically related. Here, we first confirmed that newborn G3 Terc −/− mice showed a significantly lower body weight at the time of birth compared with the wild-type controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 6, C and D, left), which again was concomitant with a lower clonogenic potential of keratinocytes derived from G3 Terc −/− mice compared with the wild types (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, the small body-size phenotype of newborn G3 Terc −/− mice was significantly corrected by telomerase reintroduction into G3 Terc +/−* newborns, paralleling the rescue of stem cell phenotypes in these mice (Figs. 4–6 ). This significant rescue of the small body-size phenotype observed in newborns was maintained when comparing age-matched adult (2 mo old) G3 Terc +/−* mice to the corresponding G3 Terc −/− littermates (P < 0.001; Fig. 6, C and D, right). These results support that the small body size of telomerase-deficient mice may be linked to decreased stem cell functionality.

Reintroduction of the telomerase Terc gene in G3 Terc-deficient mice is sufficient to rescue a normal life span in the absence of increased cancer

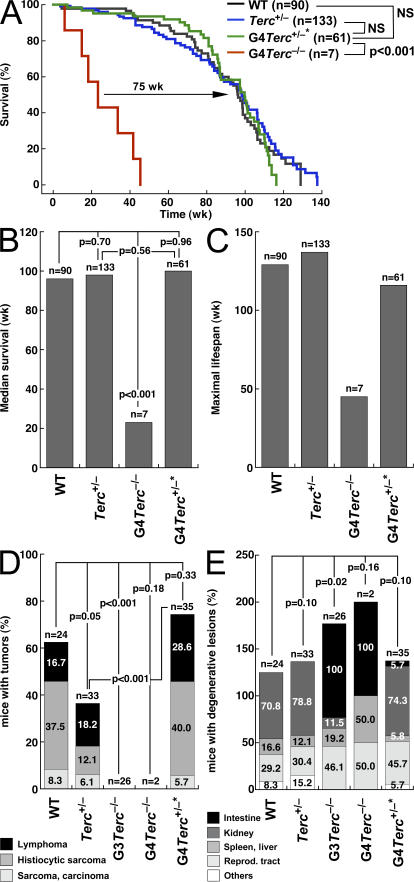

The results presented here for epidermal HF stem cells open the possibility that telomerase reintroduction into mice with critically short telomeres may be sufficient to restore stem cell functionality in different tissues, thus rescuing life span and long-term survival. To address this, we studied the long-term survival and maximum life span of both telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* and telomerase-deficient G4 Terc −/− littermates, compared with that of control wild-type mice as well as control nonreconstituted heterozygous Terc +/− mice (Fig. 7, A–C). First, we confirmed a dramatic decrease in the maximum life span of G4 Terc −/− mice compared with wild-type and Terc +/− controls, which went from ∼130 and 140 wk, respectively, to <50 wk in the case of G4 Terc −/− mice (P < 0.001; Fig. 7 A). G4 Terc −/− mice also showed a significantly decreased median survival compared with the wild-type and Terc +/− controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 7 B). Importantly, telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice showed a survival curve and a median survival that is indistinguishable from that of wild-type and Terc +/− controls (Fig. 7, A and B, NS; P = . 0.56), indicating that telomerase reintroduction into mice with critically short telomeres is sufficient to restore a normal long- term survival in these mice.

Figure 7.

Rescue of organismal life span in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc+/−* mice. (A) Kaplan-Meyer survival curve of mice of the indicated genotype. n is the number of mice of each genotype. Statistical comparisons using the log rank test are also shown. Note the significant rescue in survival of telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 Terc −/− mice (P < 0.001). (B) Median survival obtained from Kaplan-Meyer plots of mice of the indicated genotypes. Statistical comparisons using the log rank test are also shown. Note the significantly reduced median survival of G3 Terc −/− mice compared with the other genotypes (P < 0.001). (C) Maximal lifespan of mice of the indicated genotypes. Note the decreased maximal life span of G3 Terc −/− mice and how this is corrected in telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice. (D) Percentage of mice of the indicated genotype showing malignant tumors (lymphoma, histiocytic sarcoma, or sarcoma/carcinoma) at the time of death. Statistical comparisons using the χ2 test are also shown. Note the decreased incidence of malignant tumors in G3 and G4 Terc −/− mice in agreement with a tumor-suppressor role associated with telomerase deficiency and short telomeres. Telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice show a similar tumor incidence to that of wild-type controls. (E) Percentage of mice of the indicated genotype showing degenerative pathologies (atrophies) in the indicated tissues at the time of death. Statistical comparisons using the χ2 test are also shown. Note the decreased incidence of intestinal atrophies in telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice compared with G3 and G4 Terc −/− mice.

Next, we studied whether telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice had a different spectrum of cancer and aging pathologies compared with control wild-type and Terc +/− heterozygous mice. Telomerase-deficient G3 and G4 Terc −/− mice have a dramatic reduction in the incidence of malignant tumors compared with wild-type and normal Terc +/− heterozygous mice (Fig. 7 D), which is in agreement with a potent tumor suppressor role for short telomeres in the context of telomerase deficiency (Greenberg et al., 1999; Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2000; Blasco and Hahn, 2003). In contrast, G4 Terc +/−* mice showed a similar or higher incidence of malignant tumors at time of death (lymphomas, sarcomas, and carcinomas) compared with that of wild-type and Terc +/− heterozygous controls, respectively (Fig. 7 D), suggesting that telomerase reintroduction is sufficient to sustain normal tumorigenesis in G4 Terc +/−* mice. Of notice, the increased tumorigenesis in G4 Terc +/−* mice compared with nonreconstituted Terc +/− heterozygous controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 7 D) may be related to the fact that not all chromosomal defects associated with short telomeres are rescued by telomerase reintroduction (i.e., fragments and breaks; Fig. 3).

Finally, telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice also showed a significant rescue of degenerative pathologies compared with G3 and G4 Terc −/− mice. In particular, atrophies of the small intestine appeared in only 6% of G4 Terc +/−* mice at time of death compared with 100% of the G3 and G4 Terc −/− mice (Fig. 7 E). Importantly, degenerative pathologies in G4 Terc +/−* mice showed a similar incidence to those of aged-matched normal Terc +/− controls with a similar dose of the Terc allele, illustrating a complete rescue of degenerative pathologies associated with late generation Terc −/− mice. Collectively, these results suggest that telomerase reconstitution into mice with critically short telomeres is sufficient to confer a normal life span and normal aging in the absence of abnormally increased tumorigenesis.

Finally, in agreement with the similar incidence of degenerative pathologies and cancer, mean telomere length, as well as the percentages of short and long telomeres, was indistinguishable between telomerase-reconstituted G3/G4 Terc +/−* mice and the Terc +/− controls in both age-matched adult skin keratinocytes (10 mo old; Fig. 8, A and B) and primary splenocytes (12–24 mo old; Fig. 8, C and D), suggesting that telomerase activity with a normal telomere length is able to provide homeostasis during the life span of these mice.

Figure 8.

Pronounced rescue of short telomeres in Terc-reconstituted and Terc-deficient keratinocytes and splenocytes. (A) Telomere length histograms obtained by Q-FISH on tail skin sections. The histogram shown is representative of three independent age-matched (10 mo old) pairs of Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice (see B). Red lines facilitate visualization of short (<60 a.u.f.) and long (>600 a.u.f.) telomeres. The total number of telomere dots used for the quantification and the percentage of short and long telomeres are indicated. Note very similar telomere length distributions in age-matched Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice. (B) Mean telomere length is indistinguishable between age-matched Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G3 Terc +/−* mice (P = 0.98). Concomitantly, these mice show similar percentages of short telomeres (P = 0.22) and long telomeres (P = 0.70). Data are mean values ± SEM for three independent pairs of G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* mice. (C) Telomere length histograms obtained by Q-FISH directly on metaphases of freshly isolated splenocytes. The histogram shown is representative of three age-matched (1–2 yr old) pairs of Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice. In this case, arbitrary units of fluorescence were converted into kilobases as described in Materials and methods. Red lines facilitate visualization of short (<10 Kb) and long (>50 Kb) telomeres. The total number of individual telomeres used for the quantification and the percentage of short and long telomeres are indicated. Note very similar telomere length distributions in age-matched Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice. (D) Mean telomere length is indistinguishable between age-matched Terc +/− and telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice (P = 0.31). Concomitantly, these mice show similar percentages of signal-free ends (P = 0.22), short telomeres (<10 Kb; P = 0.59), and long telomeres (>50 Kb; P = 0.75). Data are mean values ± SEM for three independent Terc +/− and three independent G4 Terc +/−* mice.

Discussion

The mechanisms by which short telomeres negatively impact on organismal aging and life span are still far from being understood. One of the proposed mechanisms, which has gained increasing experimental support, is the progressive loss of stem cell functionality associated with critically short telomeres. Evidence for this comes from the study of the telomerase-deficient mouse model, which shows impaired stem cell functionality in several tissues including the bone marrow, the brain, and the skin (Lee et al., 1998; Samper et al., 2002; Ferron et al., 2004; Flores et al., 2005). In particular, we have recently shown that late generation telomerase-deficient mice show an impaired ability of epidermal stem cells to mobilize out of their niches and to regenerate the skin and the hair. This defective stem cell behavior anticipates the fact that telomerase-deficient mice show premature aging of the hair and the skin as well as an increased resistance to developing skin cancer (Lee et al., 1998; Herrera et al., 1999; Rudolph et al., 1999; Gonzalez-Suarez et al., 2000), supporting the notion that short telomeres provoke aging by impairing the functionality of stem cells.

Here, we provide further support for a stem cell theory of telomere-mediated aging by showing that telomerase reintroduction in late generation telomerase-deficient mice is sufficient to restore a normal behavior of epidermal HF stem cells and a normal skin functionality in these mice, therefore supporting the notion that stem cells are important players in the known role of telomeres and telomerase in aging. In this regard, we show that epidermal HF stem cell defects of late-generation Terc-deficient mice are independent of proliferation rates, apoptosis, or expression of the K14 and p63 differentiation markers in the skin, similar to Terc −/− and Terc +/−* mice. Indeed, the defective mobilization ability of epidermal HF stem cells anticipates the premature skin aging phenotypes of these Terc-deficient mice. Furthermore, we demonstrate that telomerase reconstitution in the context of very short telomeres not only corrects epidermal HF stem cell defects in newborn mice but is also sufficient to sustain a long-term normal organismal life span in these mice by preventing organismal aging in the absence of increased cancer. It is important to highlight that telomerase-reconstituted mice show a telomere length that is indistinguishable from that of normal, nonreconstituted, Terc heterozygous mice, indicating that telomerase activity not only elongates short telomeres but is able to restitute a normal telomere-length homeostasis during the life span of these mice.

Finally, these observations support the idea that therapies based on telomerase activation may be effective in correcting the proaging effects of short telomeres in the absence of increased risk of carcinogenesis. This is of particular relevance in the case of premature aging diseases characterized by decreased levels of telomerase activity and shorter telomeres, such as some cases of dyskeratosis congenita and aplastic anemia, which result in premature death associated with a defective tissue renewal capacity (bone marrow and skin) and increased cancer (Mason et al., 2005).

Materials and methods

Generation and genotyping of mice

To generate littermate G3/G4 Terc +/−* and G3/G4 Terc −/− mice, G2/G3 Terc −/− males were crossed with Terc +/− females (Blasco et al., 1997). Genotyping was performed as described in Blasco et al. (1997). Note that littermate G3/G4 Terc +/−* and G3/G4 Terc −/− mice are of an exact genetic background (C57BL6) as if they were derived from the same parents.

Mouse handling

Mouse colonies were generated in a pure C57BL6 background and maintained at the Spanish National Cancer Center under specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the recommendations of the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations.

Telomeric repeat amplification protocol

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were trypsinized and washed in PBS, and S-100 extracts were prepared as described in Blasco et al. (1997). Three protein concentrations were used for each sample (5, 2, and 1 μg). Extension and amplification reactions and electrophoresis were performed as described in Blasco et al. (1997). A negative control was included by preincubating each MEF extract with RNase for 10 min at 30°C before the extension reaction. An internal control for PCR efficiency was included (TRAPeze kit; Oncor).

Treatment regimens

To induce LRC mobilization, IFE hyperplasia, and anagen entry, tail skin from 71-d-old mice in the telogen (resting) phase of the hair cycle was topically treated every 48 h with TPA (20 nM in acetone) for a total of four doses. The control mice were treated with acetone only. 24 h after the last TPA treatment, mice were killed and the tail skin was analyzed. To induce anagen by physical stimulation, dorsal HFs in the telogen phase of the hair cycle were plucked from the back skin of 60-d-old G3 Terc +/−* mice and the corresponding G3 Terc −/− controls. 10 d after plucking, dorsal skins were harvested and prepared for histology.

Labeling of LRCs

LRCs were obtained as described in Bickenbach et al. (1986), Cotsarelis et al. (1990), and Braun et al. (2003), with some modifications. In brief, litters of neonatal mice were injected with 50 mg/kg of bodyweight BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in PBS. Each animal received a daily injection beginning at day 4 of life for a total of 5 d. After the labeling period, mice were allowed to grow for 60 d before the initiation of any treatment. Cells retaining the label at the end of the treatment were identified as LRCs.

Preparation of whole mounts

Whole mounts of mouse tail epidermis were prepared as previously described in Braun et al. (2003). In brief, after mice were killed with CO2 and their tails were amputated, skin was peeled from the tails and incubated in 5 mM EDTA in PBS at 37°C for 4 h. Using forceps, intact sheets of epidermis were separated from the dermis and fixed in neutral-buffered formalin for 2 h at room temperature. Fixed epidermal sheets were maintained in PBS containing 0.2% sodium azide at 4°C before labeling.

Immunofluorescence of epidermal sheets

To detect LRCs in whole mounts of the tail skin, fixed epidermal sheets were blocked and permeabilized by incubation for 30 min in a modified phosphate buffer (Braun et al., 2003) containing 0.5% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 in TBS. Subsequently, epidermal sheets were immersed for 30 min in 2 M HCl at 37°C, incubated overnight with a mouse anti-BrdU antibody conjugated with fluorescein (Roche) at 1:50 in modified PB buffer, washed four times in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20, and mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories).

Confocal microscopy

A laser scanning confocal microscope (TCS-SP2-AOBS; Leica) was used to obtain fluorescence images. Image stacks of 60–80 μm were obtained through the z dimension at steps 1.0 μm apart, using a PL APO 20×/0.70 PH2 (Leica) as lens. Maximum intensity projections of the image stacks were then generated using LCS Software (Leica).

Pathology analyses

Mice were killed when they showed signs of poor health, such as reduced activity or weight loss, and subjected to exhaustive histopathological analysis. The organs we analyzed for age-related degenerative pathologies were the intestine (atrophy of the small and large intestine), kidney (glomerulonephritis and tubular degeneration), spleen (atrophy, hemosiderosis, and myeloid and lymphoid hyperplasia), liver (congestion, vacuolar degeneration, microgranuloma, and steatosis), testis (atrophy and ectasis of seminal vesicles), ovary (atrophy), uterus (cystic endometrial hyperplasia), skin (benign hyperplasia), lung (congestion), heart (congestion and cardiomyopathy), and brain (calcification).

Histology and immunohistochemistry of skin

Tail or back skin samples were harvested from mice and fixed overnight in neutral-buffered formalin at 4°C, dehydrated through graded alcohols and xylene, and embedded in paraffin. For determination of IFE thickness, dermis thickness, and HF length, dissected skin was cut parallel to the spine and sections were cut perpendicular to the skin surface to obtain longitudinal HF sections. 5-μM sections were used for hematoxylin-eosin staining.

For immunohistochemistry, tail skin samples were sectioned at 2–3 μm and processed with 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.5, cooked under pressure for 2 min. Slides were washed in water, and then in TBS Tween 20 0.5%, blocked with peroxidase, washed with TBS Tween 20 0.5% again, and blocked with FBS followed by another wash. The slides were incubated with the primary antibodies: rabbit monoclonal to Ki-67 antibody (prediluted; SP6; Master Diagnostica), rabbit polyclonal active caspase 3 at 1:200 (R&D Systems), mouse monoclonal p63 at 1:100 (clone A48, Neomarker), or rabbit polyclonal K14 at 1:100 (Neomarker). Slides were then incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with peroxidase (DakoCytomation), goat anti-rabbit (1:50) in the case of Ki-67, active caspase 3, K14, and mouse on mouse (Vector Laboratories) in the case of p63. For signal development, DAB (DakoCytomation) was used as a substrate. Sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin and analyzed by light microscopy.

Isolation of newborn keratinocytes

2-d-old mice were killed and soaked in betadine (5 min), in a PBS antibiotic solution (5 min), in 70% ethanol (5 min), and again in a PBS antibiotic solution (5 min). Limbs and tail were amputated and the skin was peeled off using forceps. Skins were then soaked in PBS (2 min), PBS antibiotic solution (2 min), 70% ethanol (1 min), and again in PBS antibiotic solution (2 min). Using forceps, each skin was floated on the surface of 1× trypsin solution (4 ml on a 60-mm cell culture plate; Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h at 4°C. Skins were transferred to a sterile surface. The epidermis was separated from the dermis using forceps, minced, and stirred at 37°C for 30 min in serum-free Cnt-02 medium (CELLnTEC Advanced Cell Systems AG). The cell suspension was filtered through a sterile Teflon mesh (Cell Strainer 0.7 m; BD Biosciences) to remove cornified sheets. Keratinocytes were then collected by centrifugation (160 g) for 10 min and seeded on collagen I–precoated cell culture plates (BD Biosciences).

Colony-forming assay and culture conditions

1,000 mouse keratinocytes per genotype were seeded onto 10 μg/ml mitomycin C (2 h), treated with J2-3T3 fibroblasts (105 per well, 6-well dishes), and grown at 37°C/5% CO2 in Cnt-02 medium. After 10 d of cultivation, dishes were rinsed twice with PBS, fixed in 10% formaldehyde, and then stained with 1% Rhodamine B to visualize colony formation. Colony size and number were measured using three dishes per experiment.

Telomere length analysis by Q-FISH

Freshly isolated splenocytes were obtained by squeezing the spleen through a cell strainer (70 μm; Nylon; BD Biosciences). Red cells were lysed by osmotic shock, and the splenocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 0.55 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a concentration of 5 μg/ml and splenocytes were grown for 48 h. The cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/ml colcemide (Invitrogen) for 2 h and fixed in methanol/acetic acid (3:1). Q-FISH was performed as described in Herrera et al. (1999) and Samper et al. (2000). To correct for lamp intensity and alignment, images from FluoroSpheres (fluorescent beads; Invitrogen) were analyzed using the TFL-Telo software (provided by P. Lansdorp, Terry Fox Laboratory, Vancouver, Canada). Telomere fluorescence values were extrapolated from the telomere fluorescence of lymphoma cell lines LY-R (R cells) and LY-S (S cells) with known telomere lengths of 80 and 10 kb, respectively. There was a linear correlation (r2 = 0.999) between the fluorescence intensity of the R and S telomeres. We recorded the images using a camera (CCK; COHU) on a fluorescence microscope (DMRb; Leica). A mercury vapor lamp (CS 100 W-2; Philips) was used as a source. We captured the images using the Q-FISH software (Leica) in a linear acquisition mode to prevent oversaturation of fluorescence intensity. We used the TFL-Telo software (Zijlmans et al., 1997) to quantify the fluorescence intensity of telomeres from at least 10 metaphases for each data point.

Exponentially growing primary keratinocytes were fixed in methanol/acetic acid, and Q-FISH of interphase nucleus was performed. For Q- FISH in tail skin, paraffin-embedded tail sections were deparaffinated. Both keratinocytes and deparaffinated sections of tail skin were hybridized with a PNA-telomeric probe and telomere fluorescence was determined as described in Gonzalez-Suarez et al. (2000) and Muñoz et al. (2005). More than 60 nuclei from each mouse and condition were captured at 100 magnification using a microscope (CTR MIC; Leica) and a camera (High Performance CCD; COHU). Telomere fluorescence was integrated using spot IOD analysis in the TFL-TELO program (Zijlmans et al., 1997).

Cytogenetic analysis using telomere Q-FISH on metaphases

Metaphases from keratinocytes of the indicated genotypes were obtained by adding 1 μg/ml colcemide (Invitrogen) to primary keratinocytes during 5 h and then fixing in methanol/acetic acid (3:1). Q-FISH was performed as described in Herrera et al. (1999) and Samper et al. (2000). For analysis of chromosomal aberrations, 50 metaphases per genotype were analyzed by superimposing the telomere image on the DAPI image using the TFL-telo software.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, data are given as mean values ± SEM of n and have been analyzed for statistically significant differences using t test.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows rescue of HF stem cell mobilization defects in late generation telomerase-reconstituted G4 Terc +/−* mice. Fig. S2 shows similar proliferation rates in G3 Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* tail skin. Fig. S3 shows no detectable apoptosis in the skin of G3 Terc +/−* mice and G3 Terc −/− siblings. Fig. S4 shows no differences in p63 expression between Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* tail skin. Fig. S5 shows no differences in keratin 14 expression between Terc −/− and G3 Terc +/−* tail skin. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200704141/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to E. Santos and R. Serrano for mouse care and genotyping.

I. Siegel-Cachedenier is a predoctoral fellow funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture. I. Flores is a Ramon y Cajal senior scientist. M.A. Blasco's laboratory is funded by the Ministry of Education and Science (SAF2001-1869, GEN2001-4856-C13-08), Comunidad Autonoma de Madrid (08.1/0054/01), European Union (TELOSENS FIGH-CT-2002-00217, INTACT LSHC-CT-2003-506803, ZINCAGE FOOD-CT-2003-506850, RISC-RAD FI6R-CT-2003-508842, MOL CANCER MED LSHC-CT-2004-502943), and Josef Steiner Award (2003).

Abbreviations used in this paper: a.u.f., arbitrary units of fluorescence; HF, hair follicle; IFE, interfollicular epidermis; LRC, label retaining cell; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; Q-FISH, quantitative FISH; TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol- 13-acetate.

References

- Armanios, M.Y., J.J. Chen, J.D. Cogan, J.K. Alder, R.G. Ingersoll, C. Markin, W.E. Lawson, M. Xie, I. Vulto, J.A. Phillips III, et al. 2007. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:1317–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrandon, Y., and H. Green. 1987. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:2302–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickenbach, J.R., J. McCutecheon, and I.C. Mackenzie. 1986. Rate of loss of tritiated thymidine label in basal cells in mouse epithelial tissues. Cell Tissue Kinet. 19:325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, E.H. 2001. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell. 106:661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, M.A. 2005. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, M.A., and W.C. Hahn. 2003. Evolving views of telomerase and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 13:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, M.A., H.W. Lee, M.P. Hande, E. Samper, P.M. Lansdorp, R.A. DePinho, C.W. Greider. 1997. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell. 91:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, K.M., C. Niemann, U.B. Jensen, J.P. Sundberg, V. Silva-Vargas, and F.M. Watt. 2003. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 130:5241–5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canela, A., E. Vera, P. Klatt, and M.A. Blasco. 2007. High-throughput telomere length quantification by FISH and its application to human population studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:5300–5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon, R.M., K.R. Smith, E. O'Brien, A. Sivatchenko, and R.A. Kerber. 2003. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 361:393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.W., and E.H. Blackburn. 2002. New ways not to make ends meet: telomerase, DNA damage proteins and heterochromatin. Oncogene. 21:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K., and J.R. Mitchell. 2002. Telomerase in the human organism. Oncogene. 21:564–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis, G., T.T. Sun, and R.M. Lavker. 1990. Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 61:1329–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, T. 2005. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 19:2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel, E.S., E.H. Blackburn, J. Lin, F.S. Dhabhar, N.E. Adler, J.D. Morrow, and R.M. Cawthorn. 2004. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:17312–17315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron, S., H. Mira, S. Franco, M. Cano-Jaimez, E. Bellmunt, C. Ramirez, I. Farinas, and M.A. Blasco. 2004. Telomere shortening and chromosomal instability abrogates proliferation of adult but not embryonic neural stem cells. Development. 131:4059–4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, I., M.L. Cayuela, and M.A. Blasco. 2005. Effects of telomerase and telomere length on epidermal stem cell behavior. Science. 309:1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, I., R. Benetti, and M.A. Blasco. 2006. Telomerase regulation and stem cell behaviour. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, E., T. Tumbar, and G. Guasch. 2004. Socializing with the neighbours: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 116:769–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cao, I., M. García-Cao, A. Tomás-Loba, J. Martín-Caballero, J.M. Flores, P. Klatt, M.A. Blasco, and M. Serrano. 2006. Increased p53 activity does not accelerate telomere-driven aging. EMBO Rep. 7:546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Suarez, E., E. Samper, J.M. Flores, and M.A. Blasco. 2000. Telomerase-deficient mice with short telomeres are resistant to skin tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 26:114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, R.A., L. Chin, A. Femino, K.H. Lee, G.J. Gottlieb, R.H. Singer, C.W. Greider, and R.A. DePinho. 1999. Short dysfunctional telomeres impair tumorigenesis in the INK4a(delta2/3) cancer-prone mouse. Cell. 97:515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley, C.B., A.B. Futcher, and C.W. Greider. 1990. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 345:458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L. 2004. Does the reservoir for self-renewal stem from the ends? Oncogene. 23:7283–7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann, M.T., M.A. Strong, L.Y. Hao, and C.W. Greider. 2001. The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell. 107:67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, E., E. Samper, J. Martin-Caballero, J.M. Flores, H.W. Lee, and M.A. Blasco. 1999. Disease states associated to telomerase deficiency appear earlier in mice with short telomeres. EMBO J. 18:2950–2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-W., M.A. Blasco, G.J. Gottlieb, C.W. Greider, and R.A. DePinho. 1998. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 392:569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri, A., S. Franco, A. Zacheo, L. Barlucchi, S. Chimenti, F. Limana, B. Nadal-Ginard, J. Kajstura, P. Anversa, and M.A. Blasco. 2003. Ablation of telomerase and telomere loss leads to cardiac dilatation and heart failure associated with p53 upregulation. EMBO J. 22:131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, A., D. Stevens, T. Vulliamy, I. Dokal, and P.J. Mason. 2004. Heterozygous telomerase RNA mutations found in dyskeratosis congenita and aplastic anemia reduce telomerase activity via haploinsufficiency. Blood. 104:3936–3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P.J., D.B. Wilson, and M. Bessler. 2005. Dyskeratosis congenita—a disease of dysfunctional telomere maintenance. Curr. Mol. Med. 5:159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.R., E. Wood, and K. Collins. 1999. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 402:551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A., and I.R. Lemischka. 2006. Stem cells and their niches. Science. 311:1880–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R.J., Y. Liu, L. Marles, Z. Yang, C. Trempus, S. Li, J.S. Lin, J.A. Sawicki, and G. Cotsarelis. 2004. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P., R. Blanco, J.M. Flores, and M.A. Blasco. 2005. XPF nuclease-dependent telomere loss and increased DNA damage in mice overexpressing TRF2 result in premature aging and cancer. Nat. Genet. 37:1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, H., A. Rochat, C. Kedzia, K. Kobayashi, and Y. Barrandon. 2001. Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent item cells. Cell. 104:233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K.L., S. Chang, H.-W. Lee, M.A. Blasco, G. Gottlieb, C.W. Greider, and R.A. DePinho. 1999. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell. 96:701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani, N.J., R. Boultby, R. Butler, J.R. Thompson, and A.H. Goodall. 2001. Telomere shortening in atherosclerosis. Lancet. 358:472–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper, E., F.A. Goytisolo, P. Slijepcevic, P.P. van Buul, and M.A. Blasco. 2000. Mammalian Ku86 protein prevents telomeric fusions independently of the length of TTAGGG repeats and the G-strand overhang. EMBO Rep. 1:244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper, E., J.M. Flores, and M.A. Blasco. 2001. Restoration of telomerase activity rescues chromosomal instability and premature aging in Terc−/− mice with short telomeres. EMBO Rep. 2:800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samper, E., P. Fernandez, R. Equia, L. Martin-Rivera, A. Bernad, M.A. Blasco, and M. Aracil. 2002. Long-term repopulating ability of telomerase-deficient murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 99:2767–2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, K.Y., P. Cheung, D. Gilison, E. Lee, R.I. Tennen, E. Wang, M.K. Artandi, A.E. Oro, and S.E. Artandi. 2005. Conditional telomerase induction causes proliferation of hair follicle stem cells. Nature. 436:1048–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, M.T., M. Arneric, P. Sperisen, and J. Lingner. 2004. Telomere length homeostasis is achieved via a switch between telomerase-extendible and -nonextendible states. Cell. 117:323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiri, K.D., J.T. Cronkhite, P.J. Kuan, C. Xing, G. Raghu, J.C. Weissler, R.L. Rosenblatt, J.W. Shay, and C.K. Garcia. 2007. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:7552–7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar, T., G. Guasch, V. Greco, C. Blanpain, W.E. Lowry, M. Rendl, and E. Fuchs. 2004. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 303:359–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, A.M., T. Andrew, J.P. Gardner, M. Kimura, E. Oelsner, L.F. Cherkas, A. Aviv, and T.D. Spector. 2005. Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet. 366:662–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy, T., A. Marrone, F. Goldman, A. Dearlove, M. Bessler, P.J. Mason, and I. Dokal. 2001. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 413:432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy, T., A. Marrone, R. Szydlo, A. Walne, P.J. Mason, and I. Dokal. 2004. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nat. Genet. 36:447–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann, S.U., A. Satyanarayana, M. Tsahurida, H.L. Tillman, L. Zender, J. Klempnauer, P. Flemming, S. Franco, M.A. Blasco, M.P. Manns, K.L. Rudolph. 2002. Hepatocyte telomere shortening and senescence are general markers of human liver cirrhosis. FASEB J. 16:935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C., G. Cotsarelis, Z.G. Wei, E. Fryer, J. Margolis-Fryer, M. Ostead, R. Tokarek, T.T. Sun, and R.M. Lavker. 1994. Cells within the bulge region of mouse hair follicle transiently proliferate during early anagen: heterogeneity and functional differences of various hair cycles. Differentiation. 55:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, H., R.T. Calado, H. Ly, S. Kaijigaya, G.M. Baerlocher, S.J. Chanock, P.M. Lansdorp, and N.S. Young. 2005. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1413–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlmans, J.M., U.M. Martens, S.S. Poon, A.K. Raap, H.J. Tanke, R.K. Ward, and P.M. Lansdorp. 1997. Telomeres in the mouse have large inter-chromosomal variations in the number of T2AG3 repeats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:7423–7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.