Abstract

Oxygenases form an interesting class of biocatalysts, as they typically perform oxygenations with exquisite chemo-, regio-, and/or enantioselectivity. It has been observed that, once heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli, some oxygenases are able to form the blue pigment indigo. We have exploited this characteristic to screen a metagenomic library derived from loam soil and identified a novel oxygenase. This oxygenase shows 50% sequence identity with styrene monooxygenases from pseudomonads (StyA). Only a limited number of homologs can be found in the genome sequence database, indicating that this biocatalyst is a member of a relatively small family of bacterial monooxygenases. The newly identified monooxygenase catalyzes the epoxidation of styrene and styrene derivatives and forms the corresponding (S)-epoxides with excellent enantiomeric excess [e.g., (S)-styrene oxide is formed with >99% enantiomeric excess, ee] and therefore is named styrene monooxgenase subunit A (SmoA). SmoA shows high enantioselectivity towards aromatic sulfides [e.g., (R)-ethyl phenyl sulfoxide is formed with 92% ee]. This excellent enantioselectivity in combination with the moderate sequence identity forms a clear indication that SmoA from a metagenomic origin represents a new enzyme within the small family of styrene monooxygenases.

Oxygenases are of growing interest for biotechnological applications (5, 38). These oxidative biocatalysts are able to insert one or two oxygen atoms into a substrate molecule. In order to do so, they usually need NAD(P)H as an electron donating coenzyme, while a metal or organic cofactor is required for oxygen functionalization. A feature that makes these biocatalysts of special interest is their ability to perform oxygenations in a chemo-, regio-, and/or enantioselective manner (13, 38). Often, selectivities are observed that cannot be rivaled by chemical approaches. Due to their selectivity and ability to use oxygen as a cheap and environmentally friendly oxidant, oxygenases form an important class of enzymes which can be applied for the biocatalytic oxidation of several compounds. The need for expensive coenzymes is no longer considered a hurdle for such industrial applications, since biocatalytic systems employing whole cells can be used which circumvent expensive coenzyme regeneration procedures (36).

Oxygenases are found in all kingdoms of life but especially in bacteria. Their physiological role is often related to degradation of toxic compounds or the synthesis of secondary metabolites (40). The classical approach to finding novel oxygenases with biocatalytic potential is therefore to screen for organisms which are able to grow on toxic compounds, like aromatics, or to use cultures which are enriched with these kinds of compounds. However, this method only focuses on the culturable portion of organisms which contain putative oxygenases, and it is estimated that more than 99% of all microbes are not cultivable (1) and therefore not accessible as a source for finding novel biocatalysts. With the development of methods for the construction of environmental DNA libraries, this has changed, and now several examples exist of novel biocatalytically relevant enzymes originating from the metagenome (16, 22, 24, 44). Among these newly discovered enzymes, oxygenases are relatively rare. Lorenz and coworkers described finding some oxygenase-encoding genes without exploring their activities (25). A putative monooxygenase involved in the biosynthesis of (deoxy)violacein has been identified from an environmental DNA cosmid library (4), and recently a putative indole oxygenase from a forest soil metagenome has been reported (23).

It is known that several types of oxygenases, once expressed in Escherichia coli, are able to produce the blue pigment indigo (6, 9, 10, 28, 30). The formation of indigo occurs via the oxidation of indole, which is formed from tryptophan by the endogenous E. coli enzyme tryptophanase (10). So, the ability to produce indigo is related to oxygenase activity and therefore enables screening for novel oxygenases from metagenomic libraries using E. coli as a host organism.

In this paper we describe the discovery of a novel styrene monooxygenase from the metagenome by its ability to form indigo in E. coli and show that it is able to perform highly enantioselective epoxidation and sulfoxidation reactions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Alkenes were from Acros and Lancaster. Styrene oxide (racemic), (S)-styrene oxide, (R)-m-chlorostyrene oxide, methyl phenyl sulfide, methyl p-tolyl sulfide, methyl phenyl sulfoxide (racemic), methyl p-tolyl sulfoxide (racemic), (R)-methyl p-tolyl sulfoxide, and ethyl phenyl sulfide were from Aldrich. Ethyl phenyl sulfide was from Fluka. o-chloro-, m-chloro, and p-chlorostyrene oxide were synthesized in our laboratory as described previously (27). Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) was obtained from Acros, and NADH was from Sigma. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and dithiothreitol (DTT) were from Roche. Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. Formate dehydrogenase from Candida boidinii and catalase were from Fluka. Flavin reductase (phenol hydroxylase component 2 [PheA2]) was a gift from W. J. H. van Berkel, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. Phenylacetone monooxygenase was obtained as described before (14). All other chemicals were of a commercially available grade. Oligonucleotides were from Sigma-Aldrich. One-Shot electrocompetent E. coli TOP10 cells and the TOPO TA cloning kit were purchased from Invitrogen. Plasmids were isolated using the QIAGEN DNA purification kit. Constructs were sequenced at GATC Biotech (Germany).

Construction and screening of the metagenomic library.

The metagenomic library was constructed from environmental DNA isolated from loam soil using a direct isolation protocol as described before (15). The library (DirL) consisted of 80,000 clones with an average insert size of 5.5 kb and had been constructed in the pZerO-2 vector. It was freshly transformed to electrocompetent E. coli TOP 10 cells (Invitrogen) and plated on LB agar plates containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. IPTG (0.4 mM) was added to induce expression of genes which are dependent on the lac promoter (17). A total of approximately 65,000 colonies were plated this way. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 2 days and were subsequently screened for colonies which were able to produce the blue pigment indigo by visual inspection. From clones producing indigo, the plasmid was isolated and freshly transformed to E. coli cells to confirm that indigo formation was coupled to the particular plasmid. Subsequently, these plasmids were subjected to restriction analysis with EcoRI to identify the uniqueness of the clone. Unique clones were sequenced to identify the inserted fragment of metagenomic DNA.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis.

Open reading frames (ORFs) were identified using the ORF Finder tool of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). BLAST searches were performed using the BLAST function at the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), using the available DNA databases (including those from environmental samples). All identified homologs were aligned using the ClustalW program and were represented as an unrooted phylogenetic tree using TreeView.

Cloning of the styrene monooxygenase gene.

The gene encoding SmoA was amplified from the plasmid carrying the fragment of environmental DNA (pZerO-2-DirL1) using primers based on the gene sequences of homologs from Pseudomonas species and to introduce NdeI and HindIII restriction sites for cloning in the pBAD vector. Therefore, the following primers were used: smoA_fw (5′-TCTCTCATATGAGACGGCGCATCGGGAT; the NdeI site is shown in italics) and smoA_rv (5′-CGAAGCTTTCACGCCGTGGCCCGCACCGG; the HindIII site is shown in italics). The amplified gene was isolated from the gel, purified, and ligated in the pCR4-TOPO vector using the TOPO TA cloning kit. Subsequently, the TOPO vector carrying the smoA gene (pCR4-TOPOsmoA) was restricted with NdeI and HindIII, and the smoA gene was ligated in the NdeI/HindIII-digested pBAD vector behind the araBAD promoter. The pBAD vector carrying the smoA gene (psmoA) was transformed to E. coli TOP10 and E. coli MC1061 in order to obtain overexpression of the SmoA protein. Expression of SmoA was tested in both strains at 17, 30, and 37°C at concentrations of l-arabinose ranging from 0.00002 to 0.2% (wt/vol), but overexpression of SmoA failed, as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (data not shown). However, since formation of indigo was observed during these experiments, active SmoA was expressed to a limited level.

Preparation of cell extract.

In order to obtain cell extract of cells producing SmoA, E. coli TOP10 cells containing the plasmid psmoA were grown at 30°C in 500 ml of Luria-Bertani medium containing 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin and 0.02% (wt/vol) arabinose. The cells were harvested at an A600 of 1.6, centrifuged, and resuspended in 20 ml 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 containing 1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol. The cells were disrupted by sonication, and the extract was centrifuged. The supernatant was distributed in aliquots of 1 ml and immediately stored at −20°C until further usage.

Reaction conditions for SmoA-catalyzed conversions.

In order to identify substrates for SmoA, an in vitro assay based on a previously described procedure (20) was used, employing FAD reductase and formate dehydrogenase, ensuring regeneration of NADH and reduced FAD. All reactions were carried out in pyrex tubes in a total volume of 2 ml of a 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5 containing 1 mM DTT and 5% (vol/vol) glycerol. The reaction mixture contained 2 mM substrate, 50 μM FAD, 50 μM NADH, 1,500 U catalase (to prevent enzyme inactivation caused by H2O2, formed in uncoupling reactions), 0.5 U formate dehydrogenase, 150 mM sodium formate, 1.3 μM PheA2, and 0.29 mg/ml of the SmoA-containing cell extract (E. coli pBADSmoA). Controls were performed without the cell extract. The reaction was started by the addition of NADH, and the tubes were incubated at 30°C at 200 rpm. After 7 or 16 h, the reaction mixture was extracted with an equal volume of diethyl ether containing mesitylene as an internal standard. The organic phase was subsequently dried over MgSO4 for gas chromatograph (GC) analysis.

Product analysis.

In order to quantify the degree of conversion, product formation was measured using mesitylene as an internal standard on a nonchiral HP1 capillary GC column (30 m by 0.25 mm) using the following temperature program: 35°C to 200°C with 15°C/min and then 5 min at 200°C. For epoxidation and sulfoxidation reactions, samples were analyzed on a Chiraldex GTA capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm). The following programs were used: for analysis of styrene conversion, 100°C for 20 min [retention times were 3.5, 9.6, and 12.2 min for the remaining substrate and the (S)- and (R)-epoxides, respectively]; for analysis of o-chlorostyrene conversion, 120°C for 20 min [retention times were 4.7, 8.8, and 11.5 min for the remaining substrate and (R)- and (S)-epoxides, respectively]; for analysis of m-chlorostyrene conversion, 140°C for 20 min [retention times were 3.5, 6.3, and 7.6 min for the remaining substrate and (S)- and (R)-epoxides, respectively]; for analysis of p-chlorostyrene conversion, 100°C for 35 min [retention times were 6.7, 23.5, and 25.0 min for the remaining substrate and (S)- and (R)-epoxides, respectively]. For styrene oxide and m-chlorostyrene oxide, the absolute configuration was determined by comparison with enantiomerically pure (S)-styrene oxide and (R)-m-chlorostyrene oxide. For o-chlorostyrene oxide and p-chlorostyrene oxide, the absolute configurations were determined by comparison with previously determined values in our lab (27) by applying identical GC methods using the same column.

For analysis of the SmoA-catalyzed sulfoxidation reactions, the following temperature program was used: 150°C to 170°C with 10°C min−1, 17 min at 170°C, and from 170°C to 150°C with 10°C min−1. For methyl phenyl sulfide conversion, the retention times were 3.2, 7.8, and 10.6 min for the remaining substrate and the (R)- and (S)-sulfoxides, respectively. The absolute configuration of these sulfoxides was determined by a parallel experiment with phenylacetone monooxygenase, which catalyzes the enantioselective sulfoxidation of methyl phenyl sulfide and yields an excess of the (R)-sulfoxide (7, 8). For ethyl phenyl sulfide conversion, the retention times were 3.3, 8.7, and 11.1 min for the remaining substrate and the (R)- and (S)-sulfoxides, respectively. The absolute configuration of the ethyl phenyl sulfoxide was determined by a comparison with a parallel experiment which involved the enantioselective sulfoxidation reaction catalyzed by phenylacetone monooxygenase in the presence of 30% methanol. This reaction is known to selectively produce the (R)-sulfoxide (8). For methyl p-tolyl sulfide conversion, the retention times were 3.5, 9.6, and 10.3 min for the remaining substrate and the (R)- and (S)-sulfoxides, respectively. The absolute configuration was determined by comparison with commercially available (R)-methyl p-tolyl sulfoxide.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The environmental sequence reported in this study has been deposited in GenBank under accession number EF660561.

RESULTS

Enzyme discovery.

For this study a metagenomic library was used that was constructed previously using loam soil (15). Out of approximately 65,000 colonies, two clones were identified by their bright blue color. From these clones, the plasmids were isolated and subjected to restriction analysis by digestion with EcoRI. The two plasmids showed an identical restriction pattern, indicating that they were identical clones, which is possible since the metagenomic library was amplified prior to screening. When the isolated plasmid DNA was transformed to fresh E. coli TOP10 cells, all colonies turned blue again, indicating that the color formation was coupled to the isolated plasmid. Cultivation in liquid medium also resulted in a blue medium.

Sequencing the plasmid of clone 1 revealed an inserted fragment of metagenomic DNA of 3,874 bp. Five open reading frames (ORF1 to ORF5) could be identified on the fragment, from which one was truncated (ORF5) (Table 1). The protein sequences of the identified open reading frames were used for a BLAST search in order to find homologs. The products of ORF1 and ORF2 showed highest sequence identities with a putative FAD-dependent oxidoreductase and a putative flavin-reducing protein, respectively, from Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2. When we looked for homologs with known functions, it was found that the products of ORF1 and ORF2 share around 50% sequence identity with the two components of styrene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas fluorescens ST. These two components mediate epoxidation of styrene into styrene oxide and are also known for their ability to form indigo (3). They represent a two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenase consisting of a monooxygenase component (StyA), which catalyzes the actual monooxygenation reaction, and a flavin reductase (StyB), which reduces FAD to FADH2 (33). All other identified ORFs showed no homology to any known oxygenase and, therefore, it was concluded that the indigo-forming capacity must be coupled to the enzyme activity of the styrene monooxygenase homologs. To distinguish the newly discovered enzyme from the known one, we named the monooxygenase component SmoA (styrene monooxygenase subunit A) and the flavin reductase SmoB (styrene monooxygenase subunit B).

TABLE 1.

Sequence similarities of the identified ORFs from the 3,874-bp fragment of metagenomic DNA with uncharacterized and characterized homologs

| ORF (position [bp]) | Uncharacterized homologs

|

Characterized homologs

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closest homolog, NCBI accession no. | Organism | % Identitya | Closest homolog with known activity, NCBI accession no. (reference) | Organism | % Identitya | |

| ORF1 (220-1470) | FAD dependent oxidoreductase, YP_488103 | Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2 | 74 | StyA protein, CAB06823 (3) | Pseudomonas fluorescens ST | 50 |

| ORF2 (1481-1963) | Flavin reductase-like, FMN binding, YP_488101 | Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2 | 62 | StyB protein, CAB06824 (3) | Pseudomonas fluorescens ST | 48 |

| ORF3 (2650-1991) | Hypothetical protein bll7091, BAC52356 | Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | 64 | |||

| ORF4 (3300-2650) | 3-Oxoadipate succinyl-CoAb transferase B subunit, CAE29596 | Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | 95 | 3-Oxoadipate succinyl-CoA transferase B subunit, CAA51373 (2) | Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 | 72 |

| ORF5 (3385-3874) | 3-Oxoadipate succinyl-CoA transferase A subunit, BAC52358 | Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA 110 | 95 | 3-Oxoadipate succinyl-CoA transferase A subunit, CAA51372 (2) | Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 | 71 |

Based on amino acid level.

CoA, coenzyme A.

The gene encoding SmoA was cloned in the pBAD expression vector. Several growth conditions were tested to overexpress the protein. However, as judged by SDS-PAGE analysis, no condition was found under which overexpression could be achieved. Nevertheless, active protein was expressed using this construct when cells were grown at 30°C in the presence of 0.02% (wt/vol) arabinose in LB medium. Under this condition, formation of indigo was observed during cultivation. This indicates that SmoA is also active without the presence of SmoB. Probably, the FAD reductases present in E. coli can supply SmoA with reduced FAD necessary for activity and thus for the synthesis of indigo.

Sequence analysis of SmoA and SmoB.

The protein sequence of SmoA was used to perform a BLAST search in the available sequence databases (including those from sequenced genomes and environmental samples) of NCBI. SmoA shows ∼50% sequence identity with five styrene monooxygenase sequences previously identified from Pseudomonas species (3, 18, 31, 35, 43). These styrene monooxygenases are of equal size (415 residues), displaying highly similar sequence identities among each other of 94 to 99%, and can be regarded as isoforms. From the currently completely sequenced bacterial genomes (720), only a minority (28) contains one or more SmoA homologs. In particular, the genome of Nocardia farcinica is rich in these monooxygenases, as it contains six representatives. No homologs were found in sequenced genomes from archaea and eukaryotes, while only one homolog (25% sequence identity) was found in the sequenced metagenome from the Sargasso Sea. This suggests that SmoA is a member of a relatively small family of bacterial monooxygenases. While at present hundreds of bacterial cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases have been identified in all sequenced bacterial genomes, we could only find 44 sequences belonging to this newly recognized family of monooxygenases. SmoA is most related to two putative monooxygenases from R. palustris HaA2 and Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1.

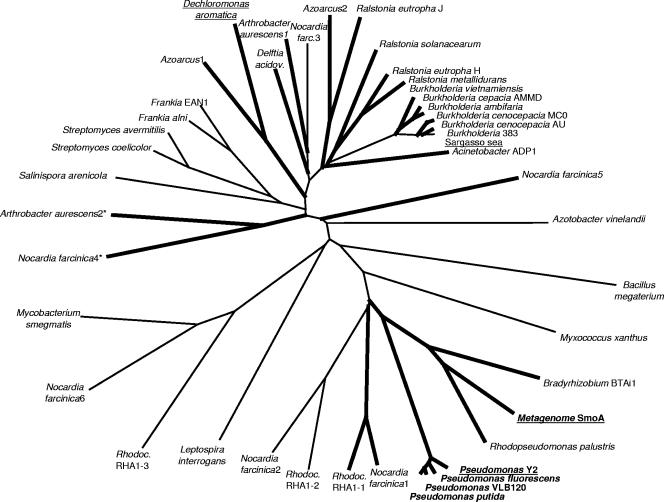

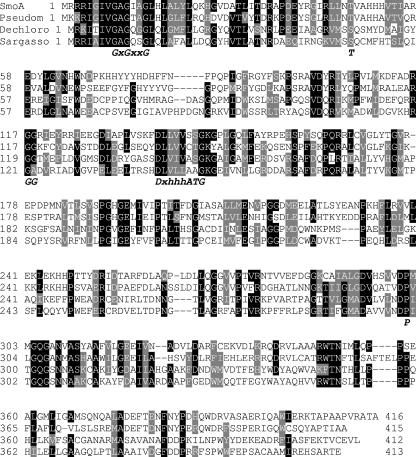

All identified homologs were aligned using ClustalW, which resulted in an unrooted phylogenetic tree of (putative) monooxygenases (Fig. 1). An alignment of a selected number of homologs shows the presence of several common sequence motifs, indicating that the N-terminal part of these monooxygenases forms a dinucleotide-binding domain (Fig. 2) (39). This is in line with the fact that StyA from Pseudomonas putida VLB120 has been shown to be FAD dependent. All homologs are similar in length and display sequence similarity throughout their sequence, suggesting that these monooxygenases share a common fold. A weak sequence similarity with FAD-containing aromatic hydroxylases suggests that styrene monooxygenases and their homologs will resemble to a limited extent the structure of, for example, 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (41), which has been confirmed by the recently published model structure of StyA (11). Of all homologs, only StyAB from P. putida VLB120 and Pseudomonas putida S12 has recently been heterologously expressed and characterized (21, 34). Of the other homologs, the corresponding activity has not yet been determined. However, it is interesting that P302 and T47, which have been suggested as catalytically important residues (11), are highly conserved. This could be an indication that in fact all of the identified homologs can catalyze epoxidation reactions.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree representation of putative epoxide-forming monooxygenases. The sequence identifiers of all used sequences are as follows, based on GI number: 2598026, Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2; 2655265, Pseudomonas sp. strain VLB120; 13897838, Pseudomonas putida; 2154927, Pseudomonas fluorescens; 2370373, Pseudomonas putida; 28894878, Bacillus megaterium; 86751607, Rhodopseudomonas palustris HaA2; 78695129, Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1; 54025215, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 111025839, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1; 111025841, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1; 54025213, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 108758031, Myxococcus xanthus DK 1622; 21223658, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2); 111221252, Frankia alni ACN14a; 29829500, Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680; 119961264, Arthrobacter aurescens TC1; 68232853, Frankia sp. strain EAN1; 17546556, Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000; 54023215, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 113869433, Ralstonia eutropha H16; 119898254, Azoarcus sp. strain BH72; 50085742, Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1; 94312250, Ralstonia metallidurans CH34; 119898229, Azoarcus sp. strain BH72; 119881494, Salinispora arenicola CNS205; 67548107, Burkholderia vietnamiensis G4; 71906976, Dechloromonas aromatica RCB; 54023216, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 119964329, Arthrobacter aurescens TC1; 73537304, Ralstonia eutropha JMP134; 115361048, Burkholderia cepacia AMMD; 107028237, Burkholderia cenocepacia AU 1054; 67155248, Azotobacter vinelandii AvOP; 78060292, Burkholderia sp. strain 383; 118708111, Burkholderia cenocepacia MC0-3; 118698162, Burkholderia ambifaria MC40-6; 24216923, Leptospira interrogans serovar Lai strain 56601; 54023186, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 118730224, Delftia acidovorans SPH-1; 111019872, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1; 54027408, Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152; 118469620, Mycobacterium smegmatis strain MC2 155; 44419368, environmental sequence from Sargasso Sea. SmoA shows 50% sequence identity with the group of closely related (≥94% identity) styrene monooxygenases from Pseudomonas species for which activity has been experimentally confirmed. The branches in thick lines contain those sequences for which a putative reductase component has been identified in close proximity to the oxygenase-encoding gene in the respective genome. Two monooxygenases contain a fused reductase domain, indicated by an asterisk. The sequences that are underlined were used for the multiple sequence alignment shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of styrene monooxygenases and putative monooxygenases. Sequence motifs indicative of a dinucleotide-binding domain binding the FAD coenzyme are indicated in italics (39). SmoA, the styrene monooxygenase described in this study; Pseudom, styrene monooxygenase subunit from Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2; Dechloro, a putative monooxygenase from Dechloromonas aromatica RCB; Sargasso, a putative monooxygenase identified in the sequence metagenome from the Sargasso Sea (see Fig. 1 for sequence identifiers). The conserved proline (P) and threonine/serine (T/S) which have recently been identified as catalytically important residues in a model structure of StyA (11) are also indicated.

The protein sequence of SmoB shows homology with other flavin reductases. The highest sequence identities (62 to 47%) are found with the flavin reductases from Pseudomonas species, R. palustris HaA2, and Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1. The genes which encode these reductases are all in close proximity on the respective genomes to the genes encoding the (putative) monooxygenases, which indicates that these (putative) monooxygenases are indeed two-component flavin-dependent monooxygenases (class E flavoprotein monooxygenases) (41). SmoB also shows 38% sequence identity with PheA2 from Bacillus thermoglucosidasius, for which a crystal structure has been determined (42). This enabled us to construct a structural model of the SmoB using the CHPmodels 2.0 server (data not shown). This model nicely shows that the model structure of SmoB is highly identical with that of PheA2, as both the FAD cofactor-binding site and the NADH coenzyme/FAD substrate-binding groove are conserved. Besides FAD, PheA2 can also reduce FMN and riboflavin. Experiments with the cell extract of the original clone from the metagenomic library, encoding both SmoA and SmoB, showed only conversion of styrene into styrene oxide when we added FAD. Without FAD or with addition of FMN or riboflavin, no styrene conversion was observed. This indicates that, while SmoB may form reduced riboflavin or FMN, SmoA, like StyA from Pseudomonas, is strictly dependent on reduced FAD.

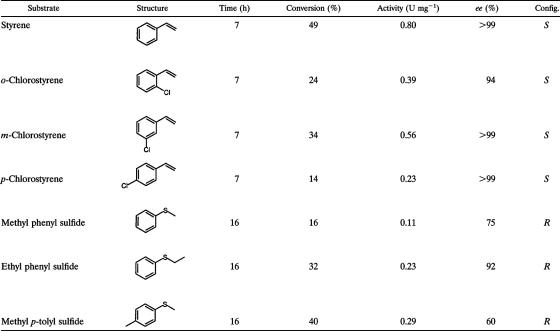

Epoxidations catalyzed by SmoA.

To investigate if SmoA can catalyze epoxidation reactions, like StyA from P. putida isolates, styrene and styrene derivatives were tested as substrates using cell extract. It was found that SmoA was active with styrene and several other substituted aromatic alkenes (Table 2). As the enzyme readily accepts styrene as a substrate, it indeed can be called a styrene monooxygenase. The linear alkene, 1-octene, and the cyclic alkenes, cyclohexene and vinylcyclohexane, were not converted by SmoA. Since the styrene monooxygenases from pseudomonads are known to be enantioselective enzymes (29), we also tested the enantioselectivity of SmoA for several compounds. This revealed that SmoA is also highly enantioselective, since it is able to convert aromatic alkenes into the (S)-epoxides with an excellent enantiomeric excess (Table 2). The enantioselectivity of SmoA is similar to that of StyA from P. putida VLB120. The latter selectively produces the (S)-epoxides of styrene, m-chlorostyrene, and p-chlorostyrene with enantiomeric excess (ee) values of ≥98% (20, 37). However, the enantioselective formation of (S)-o-chlorostyrene oxide has not been described for StyA.

TABLE 2.

Conversion of aromatic alkenes and sulfides by SmoAa

The activity was calculated as a specific activity in U mg−1 SmoA (1 U = 1 μmol min−1). The amount of SmoA present in the cell extract was estimated to be 1% of the total amount of protein, based on SDS-PAGE. For each substrate, multiple (two to five) conversions have been analyzed at different time intervals, yielding similar activities and ee values (deviation < 10%). Config., configuration.

Sulfoxidations catalyzed by SmoA.

For StyA from P. putida VLB120, it has been reported that it can catalyze sulfoxidation reactions, but with poor enantioselectivity (20). To probe whether SmoA is also able to catalyze sulfoxidation reactions, we tested several aromatic sulfides. All of them were found to be substrates for SmoA and were enantioselectively oxidized to the (R)-sulfoxides with good to excellent ee (Table 2). The best enantioselectivity was observed with ethyl phenyl sulfide, which yielded the (R)-ethyl phenyl sulfoxide with 92% ee. For StyA, only very low enantioselectivity for sulfoxidation of aromatic sulfides has been reported (e.g., StyA-mediated conversion of ethyl phenyl sulfide resulted in only 13% ee for the corresponding sulfoxide) (20).

DISCUSSION

By screening a metagenomic library from loam soil (65,000 clones), we have identified a clone expressing monooxygenase activity by its ability to form indigo. This confirms the general trend that the discovery of novel oxygenases from the metagenome is not straightforward. Some examples exist of metagenome-derived oxygenases; however, the success rate (the number of positives divided by the library size) is relatively low. For instance, Lorenz et al. found five oxygenases out of a library of 3,600,000 clones with an average insert size of 7 kb (25). This low yield of novel oxygenases can be explained by a number of different factors. Oxygenases typically occur in organisms which are involved in the aerobic degradation of toxic or complex compounds, limiting the number of oxygenase-rich microbes. Furthermore, oxygenases are complex enzymes: they are often unstable, are coenzyme dependent, can consist of several components, and are often membrane bound (40). The success rate of finding oxygenases is also dependent on the screening strategy used. This includes the library construction (source of DNA, number of clones, and average insert size of metagenomic DNA) and the choice of host organism. Genes encoding oxygenases have to be expressed in sufficient quantities, and the expressed enzyme should be stable and active enough to detect the particular clone by its enzyme activity. Also, the product should be nontoxic for the expression host.

SmoA displays only moderate sequence identity with the styrene monooxygenase from pseudomonads (StyA). Like StyA, it catalyzes the enantioselective epoxidation of styrene and styrene-like compounds, resulting in the formation of the (S)-epoxides with excellent enantiomeric excess. For StyA, it has been reported that it can also catalyze sulfoxidation reactions, but with low enantioselectivity (20). In contrast to StyA, SmoA is highly enantioselective in the formation of aromatic sulfoxides, which are important synthons for enantiopure pharmaceuticals (12). For SmoA-catalyzed conversion of styrene, an average specific activity of 0.8 U mg−1 protein was estimated (Table 2). This activity is in the same range as what has been described for purified recombinant StyA (2.1 U mg−1) (34). Therefore SmoA can be regarded as a possible alternative biocatalyst for asymmetric synthesis of both epoxides and sulfoxides.

The organism from which we have isolated the SmoA-encoding DNA fragment appears to be closely related to R. palustris HaA2 and Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1, two bacteria for which the genome has been sequenced. Both organisms contain genes encoding putative 3-oxoadipate transferase subunits as well as genes encoding putative two-component styrene monooxygenases which show high sequence identity with the uncovered metagenomic genes. So far, all described two-component styrene monooxygenases originated from pseudomonads and have been shown to be part of an operon (styABCD) which encodes aerobic styrene degradation by side chain oxidation (32). The smoAB genes and homologs in R. palustris HaA2 and Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1 are not part of such an operon. Also, no clear homologs of the styC and styD genes can be found in either microbe. Unfortunately, of all presently known SmoA homologs (Fig. 1), no three-dimensional structure is known. Only for the representatives from Pseudomonas species has it been confirmed that they are primarily active with styrene. Therefore, the physiological substrate of SmoA is unknown. The absence of the styABCD-type operon in the metagenome DNA fragment and the observed activity and good enantioselectivity for aromatic sulfides suggest that SmoA could also have a different metabolic function than the enzymes from pseudomonads.

The interaction between the monooxygenase component and the flavin reductase component of StyAB and other two-component monooxygenases has been a subject of discussion for quite some time now (26, 33). Kantz et al. have recently suggested a model in which the flavin cosubstrate is able to shuttle between StyA and StyB, during which the adenine part of the FAD coenzyme stays bound to the monooxygenase component (21). However, it has also been shown that StyA does not need StyB in order to be active (19). Using cell extracts, we have also observed that SmoA is able to convert styrene in the absence of SmoB. Apparently, no specific interaction between SmoA and SmoB is required for activity. As E. coli also contains enzymes able to form reduced flavins, expression of only SmoA is sufficient to obtain styrene epoxidation activity. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that for most of the putative epoxide-forming monooxygenase genes that we have identified (Fig. 1), a reductase gene is found next or close to the monooxygenase gene on the respective genome. Also, the phylogenetic tree representation of the putative reductase components is similar to that of the corresponding monooxygenase components (data not shown). This indicates that the genes encoding these two components have evolved together and suggests that the combined expression of such a monooxygenase and a reductase is beneficial for enzyme functioning. Interestingly, the most intimate interaction between a SmoA-like monooxygenase and a reductase component has been observed for two newly sequenced genes from Arthrobacter aurescens and Nocardia farcinia: in both genomes a gene was found in which the two components are fused at the genetic level (Fig. 1).

Acknowledgments

We thank E. M. Gabor for providing the metagenomic library and W. J. H. van Berkel for the gift of PheA2.

This research was financially supported by the Integrated Biosynthesis Organic Synthesis (IBOS) program of The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armengaud, J., K. N. Timmis, and R. M. Wittich. 1999. A functional 4-hydroxysalicylate/hydroxyquinol degradative pathway gene cluster is linked to the initial dibenzo-p-dioxin pathway genes in Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 181:3452-3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltrametti, F., A. M. Marconi, G. Bestetti, C. Colombo, E. Galli, M. Ruzzi, and E. Zennaro. 1997. Sequencing and functional analysis of styrene catabolism genes from Pseudomonas fluorescens ST. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady, S. F., C. J. Chao, J. Handelsman, and J. Clardy. 2001. Cloning and heterologous expression of a natural product biosynthetic gene cluster from eDNA. Org. Lett. 3:1981-1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bühler, B., and A. Schmid. 2004. Process implementation aspects for biocatalytic hydrocarbon oxyfunctionalization. J. Biotechnol. 113:183-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, H. S., J. K. Kim, E. H. Cho, Y. C. Kim, J. I. Kim, and S. W. Kim. 2003. A novel flavin-containing monooxygenase from Methylophaga sp. strain SK1 and its indigo synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306:930-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Gonzalo, G., D. E. Torres Pazmiño, G. Ottolina, M. W. Fraaije, and G. Carrea. 2005. Oxidations catalyzed by phenylacetone monooxygenase from Thermobifida fusca. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 16:3077-3083. [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Gonzalo, G., G. Ottolina, F. Zambianchi, M. W. Fraaije, and G. Carrea. 2006. Biocatalytic properties of Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases in aqueous-organic media. J. Mol. Catal. B 39:91-97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doukyu, N., K. Toyoda, and R. Aono. 2003. Indigo production by Escherichia coli carrying the phenol hydroxylase gene from Acinetobacter sp. strain ST-550 in a water-organic solvent two-phase system. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:720-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ensley, B. D., B. J. Ratzkin, T. D. Osslund, M. J. Simon, L. P. Wackett, and D. T. Gibson. 1983. Expression of naphthalene oxidation genes in Escherichia coli results in the biosynthesis of indigo. Science 222:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feenstra, K. A., K. Hofstetter, R. Bosch, A. Schmid, J. N. Commandeur, and N. P. Vermeulen. 2006. Enantioselective substrate binding in a monooxygenase protein model by molecular dynamics and docking. Biophys. J. 91:3206-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez, I., and N. Khiar. 2003. Recent developments in the synthesis and utilization of chiral sulfoxides. Chem. Rev. 103:3651-3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fishman, A., Y. Tao, L. Rui, and T. K. Wood. 2005. Controlling the regiospecific oxidation of aromatics via active site engineering of toluene para-monooxygenase of Ralstonia pickettii PKO1. J. Biol. Chem. 280:506-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraaije, M. W., J. Wu, D. P. H. M. Heuts, E. W. van Hellemond, J. H. Lutje Spelberg, and D. B. Janssen. 2005. Discovery of a thermostable Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase by genome mining. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 66:393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabor, E. M., E. J. de Vries, and D. B. Janssen. 2003. Efficient recovery of environmental DNA for expression cloning by indirect extraction methods. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabor, E. M., E. J. de Vries, and D. B. Janssen. 2004. Construction, characterization, and use of small-insert gene banks of DNA isolated from soil and enrichment cultures for the recovery of novel amidases. Environ. Microbiol. 6:948-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabor, E. M., W. B. L. Alkema, and D. B. Janssen. 2004. Quantifying the accessibility of the metagenome by random expression cloning techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 6:879-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmans, S., M. J. van der Werf, and J. A. de Bont. 1990. Bacterial degradation of styrene involving a novel flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent styrene monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1347-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollmann, F., K. Hofstetter, T. Habicher, B. Hauer, and A. Schmid. 2005. Direct electrochemical regeneration of monooxygenase subunits for biocatalytic asymmetric epoxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:6540-6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollmann, F., P. C. Lin, B. Witholt, and A. Schmid. 2003. Stereospecific biocatalytic epoxidation: the first example of direct regeneration of a FAD-dependent monooxygenase for catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:8209-8217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kantz, A., F. Chin, N. Nallamothu, T. Nguyen, and G. T. Gassner. 2005. Mechanism of flavin transfer and oxygen activation by the two-component flavoenzyme styrene monooxygenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 442:102-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knietsch, A., T. Waschkowitz, S. Bowien, A. Henne, and R. Daniel. 2003. Metagenomes of complex microbial consortia derived from different soils as sources for novel genes conferring formation of carbonyls from short-chain polyols on Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5:46-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, H. K., E. J. Chung, J. C. Kim, G. J. Choi, K. S. Jang, Y. R. Chung, K. Y. Cho, and S. W. Lee. 2005. Characterization of a forest soil metagenome clone that confers indirubin and indigo production on Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7768-7777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenz, P., K. Liebeton, F. Niehaus, and J. Eck. 2002. Screening for novel enzymes for biocatalytic processes: accessing the metagenome as a resource of novel functional sequence space. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 13:572-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz, P., K. Liebeton, F. Niehaus, J. Eck, and H. Zinke. 2001. Novel enzymes from unknown microbes direct cloning of the metagenome, p. 379. Proc. 5th Int. Symp. Biocatalysis Biotransform., 2-7 Sept. 2001, Darmstadt, Germany.

- 26.Louie, T. M., X. S. Xie, and L. Y. Xun. 2003. Coordinated production and utilization of FADH2 by NAD(P)H-flavin oxidoreductase and 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase. Biochemistry 42:7509-7517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutje Spelberg, J. H., R. Rink, R. M. Kellogg, and D. B. Janssen. 1998. Enantioselectivity of a recombinant epoxide hydrolase from Agrobacterium radiobacter. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 9:459-466. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mermod, N., S. Harayama, and K. N. Timmis. 1986. New route to bacterial production of indigo. Biotechnology (New York) 4:321-324. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mooney, A., P. G. Ward, and K. E. O'Connor. 2006. Microbial degradation of styrene: biochemistry, molecular genetics, and perspectives for biotechnological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Connor, K. E., A. D. W. Dobson, and S. Hartmans. 1997. Indigo formation by microorganisms expressing styrene monooxygenase activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4287-4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Leary, N. D., K. E. O'Connor, W. Duetz, and A. D. W. Dobson. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of styrene degradation in Pseudomonas putida CA-3. Microbiology 147:973-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Leary, N. D., K. E. O'Connor, and A. D. W. Dobson. 2002. Biochemistry, genetics and physiology of microbial styrene degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:403-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otto, K., K. Hofstetter, B. Witholt, and A. Schmid. 2002. Purification and characterization of SMO: a novel NADH dependent two-component flavoprotein, p. 1027. Flavins and Flavoproteins 2002, Proc. 14th Int. Symp. 14-18 July 2002, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 34.Otto, K., K. Hofstetter, M. Rothlisberger, B. Witholt, and A. Schmid. 2004. Biochemical characterization of StyAB from Pseudomonas sp. strain VLB120 as a two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 186:5292-5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panke, S., B. Witholt, A. Schmid, and M. G. Wubbolts. 1998. Towards a biocatalyst for (S)-styrene oxide production: characterization of the styrene degradation pathway of Pseudomonas sp. strain VLB120. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2032-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmid, A., J. S. Dordick, B. Hauer, A. Kiener, M. Wubbolts, and B. Witholt. 2001. Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow. Nature 409:258-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmid, A., K. Hofstetter, H. J. Feiten, F. Hollmann, and B. Witholt. 2001. Integrated biocatalytic synthesis on gram scale: the highly enantioselective preparation of chiral oxiranes with styrene monooxygenase. Adv. Synth. Catal. 343:732-737. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urlacher, V. B., and R. D. Schmid. 2006. Recent advances in oxygenase-catalyzed biotransformations. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 10:156-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallon, O. 2000. New sequence motifs in flavoproteins: evidence for common ancestry and tools to predict structure. Proteins 38:95-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Beilen, J. B., W. A. Duetz, A. Schmid, and B. Witholt. 2003. Practical issues in the application of oxygenases. Trends Biotechnol. 21:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Berkel, W. J. H., N. M. Kamerbeek, and M. W. Fraaije. 2006. Flavoprotein monooxygenases, a diverse class of oxidative biocatalysts. J. Biotechnol. 124:670-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Heuvel, R. H. H., A. H. Westphal, A. J. Heck, M. A. Walsh, S. Rovida, W. J. H. van Berkel, and A. Mattevi. 2004. Structural studies on flavin reductase PheA2 reveal binding of NAD in an unusual folded conformation and support novel mechanism of action. J. Biol. Chem. 279:12860-12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velasco, A., S. Alonso, J. L. Garcia, J. Perera, and E. Diaz. 1998. Genetic and functional analysis of the styrene catabolic cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain Y2. J. Bacteriol. 180:1063-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voget, S., C. Leggewie, A. Uesbeck, C. Raasch, K. E. Jaeger, and W. R. Streit. 2003. Prospecting for novel biocatalysts in a soil metagenome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6235-6242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]