Abstract

When dendritic cells (DCs) encounter signals associated with infection or inflammation, they become activated and undergo maturation. Mature DCs are very efficient at presenting antigens captured in association with their activating signal but fail to present subsequently encountered antigens, at least in vitro. Such impairment of MHC class II (MHC II) antigen presentation has generally been thought to be a consequence of down-regulation of endocytosis, so it might be expected that antigens synthesized by the DCs themselves (for instance, viral antigens) would still be presented by mature DCs. Here, we show that DCs matured in vivo could still capture and process soluble antigens, but were unable to present peptides derived from these antigens. Furthermore, presentation of viral antigens synthesized by the DCs themselves was also severely impaired. Indeed, i.v. injection of pathogen mimics, which caused systemic DC activation in vivo, impaired the induction of CD4 T cell responses against subsequently encountered protein antigens. This immunosuppressed state could be reversed by adoptive transfer of DCs loaded exogenously with antigens, demonstrating that impairment of CD4 T cell responses was due to lack of antigen presentation rather than to overt suppression of T cell activation. The biochemical mechanism underlying this phenomenon was the down-regulation of MHC II–peptide complex formation that accompanied DC maturation. These observations have important implications for the design of prophylactic and therapeutic DC vaccines and contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms causing immunosuppression during systemic blood infections.

Keywords: adjuvants, antigen presentation, endocytosis, immunosuppression, immunotherapy

Dendritic cells (DCs) have a high capacity to endocytose antigens and present them on their MHC class II (MHC II) molecules (reviewed in ref. 1). Endocytosis and MHC II-restricted presentation are developmentally regulated during the process of DC maturation (reviewed in ref. 2). In their immature state, DCs are highly endocytic and express low amounts of MHC II molecules on their plasma membrane. Pathogen-associated compounds such as those recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) activate immature DCs, which then undergo dramatic phenotypic changes that culminate in the acquisition of a “mature” phenotype. Mature DCs down-regulate macropinocytosis and phagocytosis, although they retain their micropinocytic activity (3, 4). Mature DCs accumulate long-lived surface MHC II–peptide complexes, derived from antigens contained within the endosomal compartments at the time of activation (5–10, 55). Such antigens correspond to proteins captured from the extracellular medium (exogenous), or those synthesized by the DCs themselves (endogenous). The latter include components of the endocytic route, plasma membrane proteins, and even cytosolic proteins transferred to endosomal compartments by autophagocytosis (1). Down-regulation of MHC II–peptide complex turnover allows long-term presentation of antigens captured, or synthesized, at the time of activation (“antigenic memory”) (2).

Once DCs mature, they lose their capacity to present newly encountered antigens (2). This is usually attributed to down-regulation of endocytosis, but it is unclear whether other factors downstream of antigen uptake also contribute to poor presentation of new antigens. It is also important to note that DC maturation has been primarily characterized by using in vitro culture systems, and it is unclear whether DCs maturing in vivo also down-regulate MHC II presentation (11–13). This is an important question because the outcome of vaccination strategies based on antigen targeting to DCs (14–17), or on loading of DCs with tumor antigens ex vivo (18), might be affected by the maturational status of the DCs. Furthermore, bacterial infections of the blood (sepsis) or parasite infections (e.g., malaria) can cause systemic DC maturation (19–21) and, concomitantly, immunosuppression (21–23). Defining the role of systemic DC maturation on this immunosuppression, and the mechanisms controlling MHC II antigen presentation by DCs, might provide strategies for restoring immunocompetence.

Here, we demonstrate that activated DCs are no longer capable of presenting newly encountered antigens via MHC II either in vitro or in vivo. This is due primarily to impaired formation of new MHC II–peptide complexes in mature DCs, rather than to down-regulation of antigen uptake or processing. Indeed, presentation of an endogenous viral antigen was also impaired in mature DCs infected with influenza virus. Furthermore, mice injected intravenously with TLR ligands, which causes systemic DC maturation, could not induce CD4 T cell responses against subsequently inoculated soluble antigen. This immunosuppression could be reversed by adoptive transfer of DCs preloaded with peptide antigen, showing that lack of T cell proliferation in the TLR ligand-treated mice was due to impaired antigen presentation rather than to general suppression of T cell activation. Our results identify a likely mechanism responsible for the immunosuppression that accompanies systemic blood infections and provides important clues for the rational design of vaccination strategies and DC-based immunotherapeutic treatments.

Results

Systemic Activation of DCs Prevents MHC II-Restricted Presentation of Subsequently Encountered Soluble Antigens.

Virtually all of the “conventional” (CD11chigh) DCs contained in mouse spleens, and approximately one-half of those contained in the lymph nodes, are “resident” DC types that develop directly within the lymphoid organs from pre-DC precursors (refs. 24 and 25; reviewed in ref. 26). These DCs have a classical immature phenotype, characterized by high phagocytic activity, accumulation of MHC II molecules in endosomal compartments, and relatively low surface expression of MHC II, CD86, and CD40 (Fig. 1A and data not shown) (27). Intravenous injection of TLR ligands such as cytosine-phosphate-guanine-rich oligonucleotide 1668 (CpG), LPS, or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid, or infection with the malaria parasite, Plasmodium berghei, causes systemic activation of these resident DCs, which then up-regulate their expression of maturation markers (Fig. 1A and data not shown) (19, 21, 27).

Fig. 1.

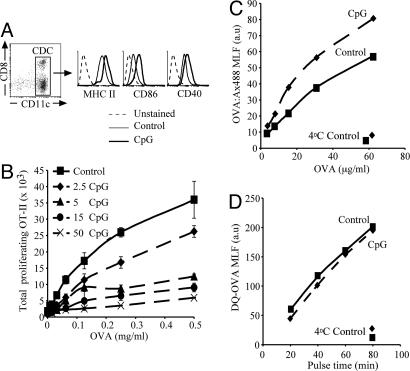

DC preactivation inhibits MHC II presentation of soluble antigen but not soluble antigen uptake or processing. (A) Surface expression of MHC II, CD86, and CD40 on purified DCs of control (thin line) or CpG-pretreated (bold line) mice. Histograms show the expression on DCs gated as shown in the dot plot (Left). The dashed line represents the background fluorescence of unstained cells. Flow cytometry profiles are representative of multiple experiments. (B) Purified DCs from control mice or mice injected i.v. 9 h earlier with the indicated amounts of CpG (2.5–50 nmol) were incubated for 45 min with the indicated concentrations of soluble OVA, washed, and cultured with CFSE-labeled OT-II cells. The number of proliferating (CFSE-low) OT-II cells was determined 60 h later. All determinations were performed in duplicate, and results represent the mean; error bars indicate SD. The results shown are representative of two experiments. (C and D) Control (continuous line) or preactivated (dashed line) DCs were incubated for 45 min with the indicated concentrations of OVA:Ax488 (C) or 1 mg/ml DQ-OVA (D) for up to 80 min at either 37 or 4°C. The MLF values for the channel corresponding to Ax488 (C) or fluorescent products of DQ-OVA degradation (D) were measured by flow cytometry. All determinations were performed in duplicate, and results represent the mean. The results shown are representative of two to three experiments.

To assess the effect of in vivo preactivation on the antigen-presenting function of DCs, we purified splenic DCs from control mice, or mice treated with CpG 9 h earlier, and tested their capacity to present soluble ovalbumin (OVA) to naive OT-II cells. DCs from normal mice presented the antigen and, as they spontaneously matured during the assay, stimulated OT-II proliferation (Fig. 1B). Injection of CpG had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on induction of OT-II proliferation (Fig. 1B). DCs from control or CpG-pretreated mice induced comparable OT-II responses if they were incubated with synthetic OVA323–339 peptide to bypass the requirement for intracellular antigen processing [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6A]. Furthermore, DCs from control or CpG-pretreated act-mOVA mice, which express a transgenic membrane-bound form of OVA, also induced OT-II proliferation similarly (SI Fig. 6B). Therefore, DCs from CpG-pretreated animals were impaired in their capacity to process and present newly encountered antigens, but not in their capacity to stimulate T cells (if peptide loaded or expressing the antigen).

One mechanism that might account for the poor presentation of OVA by mature DCs could be poor antigen capture. Indeed, we have previously demonstrated that mature DCs cannot cross-present cell-associated antigens via MHC I, nor present them via MHC II, because they down-regulate phagocytosis, the mechanism involved in uptake of cells (21). Soluble OVA, however, can be captured by pinocytosis, a form of endocytosis that persists in mature DCs (3, 4). Therefore we assessed uptake and degradation of soluble OVA by DCs from control or CpG-treated mice. Both groups of DCs endocytosed comparable amounts of a fluorescent form of soluble OVA coupled to the pH-insensitive fluorochrome Alexa 488 (Fig. 1C), and generated with comparable kinetics fluorescent degradation products on endocytosis of DQ-OVA, a self-quenched form of fluorescent OVA (Fig. 1D). Endocytosis and degradation of soluble antigen was thus unaffected in mature DCs.

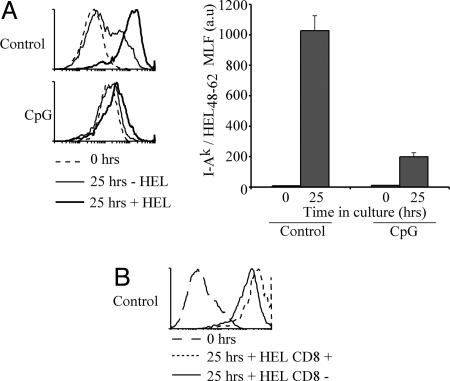

To more directly compare the ability of immature and mature DCs to load their MHC II molecules with newly encountered antigens, we used the mAb AW3.1, which recognizes the hen egg lysozyme (HEL)-derived peptide HEL48–62 bound to I-Ak (28, 29). We purified splenic DCs from control or CpG-pretreated CBA mice, incubated them with or without HEL for 25 h, and measured accumulation of I-Ak-HEL48–62 complexes on the cell surface by flow cytometry. AW3.1 showed some cross-reactivity with I-Ak molecules devoid of HEL48–62. This caused a shift in the FACS profile of the control DCs incubated without HEL at the end of the 25 h of incubation (Fig. 2A) because of the increase in total surface expression of MHC II during DC maturation (Fig. 1A). Accumulation of I-Ak-HEL48–62 complexes on the surface of control DCs incubated with HEL was clearly observed as a shift in the flow cytometry profile above this background (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the flow cytometry profile of AW3.1 reactivity hardly increased above the background staining in CpG-pretreated DCs incubated with or without HEL (Fig. 2A), indicating that mature DCs did not generate I-Ak-HEL48–62 complexes during the 25-h incubation with the antigen. This confirmed that mature DCs are inefficient at loading their MHC II molecules with peptides derived from antigens encountered after reaching the mature state.

Fig. 2.

Mature DCs are no longer able to present newly encountered antigens. (A) Purified DCs from control (Upper) or CpG-pretreated (Lower) CBA mice were incubated with or without 1 mg/ml HEL for 25 h and stained with the mAb AW3.1. The accumulation of I-Ak-HEL48–62 was assessed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry profiles from two experiments are shown. The dashed line shows the staining level before incubation. The bar graph (Right) displays the MLF values of samples incubated with HEL after subtraction of the values in the corresponding samples incubated without HEL. The result represents the mean of duplicate samples; error bars indicate SD. The results shown are representative of two experiments. (B) As in A, but using segregated CD8+ and CD8− DCs purified from control mice. The result is representative of two experiments with each sample performed in duplicate.

Splenic DCs can be subdivided into two major groups, CD8+ DCs and CD8− DCs (30, 31). It has been shown that the CD8+ DCs are less efficient at MHC II presentation of antigens captured by phagocytosis or by the surface receptor CD205 (17, 32). However, it is unclear whether this is caused by an overall deficiency in formation of MHC II–peptide complexes in the CD8+ DCs or because of poor delivery of antigen into the MHC II presentation pathway. To address this, we compared the formation of I-Ak-HEL48–62 complexes in the CD8+ and CD8− DCs. As shown previously (28, 33), both subsets presented comparable amounts of the I-Ak-HEL48–62 complexes (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, both subsets were equally impaired in formation of new complexes once they had reached the mature stage (data not shown).

Mature DCs Cannot Present Newly Encountered Endogenous Viral Antigens via MHC II.

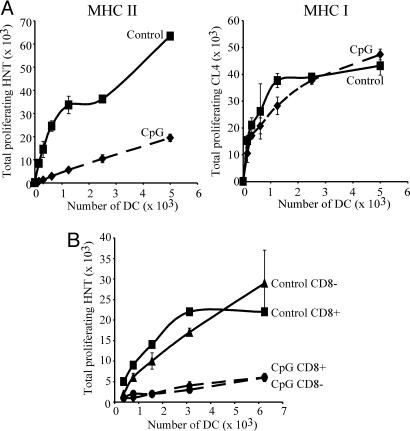

To further investigate whether the inability of mature DCs to present newly encountered antigens was attributable to lack of antigen capture, we measured the presentation of an endogenous viral antigen. We purified DCs from control and CpG-pretreated BALB/c mice and infected them in vitro with influenza virus. The cells were washed and then incubated with carboxylfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled HNT cells, which recognize the influenza hemagglutinin (HA)126–138 peptide bound to I-Ad molecules. As a membrane protein, HA is processed in endosomal compartments and is therefore readily presented via MHC II by influenza-infected cells. Thus, the infected immature DCs obtained from control animals presented the viral epitope and, as they matured in vitro, induced HNT proliferation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the already mature DCs from CpG-treated animals induced little HNT proliferation (Fig. 3A). The two sets of DCs presented an MHC I-restricted epitope derived from HA with similar efficiency, as measured by parallel assessments of proliferation of H2-Kd-restricted, HA512–520-specific CL4 T cells (Fig. 3A). This discarded the possibility that differences in viral infectivity, or in the level of expression of HA in the infected cells, were responsible for the contrast in presentation of the HNT epitope between the two DC groups. The CD8+ and CD8− DC subsets were comparable in their capacity to present HA via MHC II, and this presentation was equally impaired in both subsets on maturation (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Mature DCs are impaired in their ability to present MHC II-restricted endogenous viral antigens. (A) DC preparations from control (continuous line) or CpG-pretreated (dashed line) BALB/c mice were infected in vitro with influenza virus at 5 pfu per cell. The DCs were purified and incubated with CFSE-labeled HNT (Left) or CL4 (Right) T cells. T cell proliferation was determined 60 h later. (B) As in A, but the CD8+ and CD8− subsets from control mice were separated after infection, and then incubated with HNT cells. All determinations were performed in duplicate; results represent the mean; error bars indicate SD. The results shown are representative of two to six experiments.

Impaired Antigen Presentation Is Caused in Mature DCs by Down-Regulation of MHC II Synthesis.

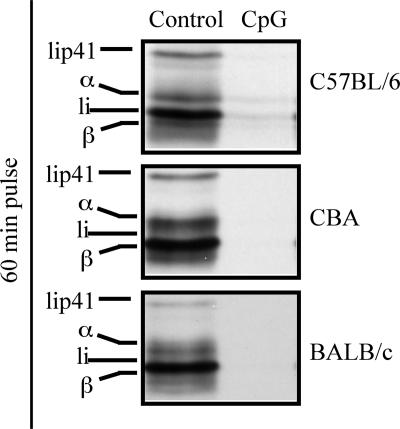

Our results demonstrate that mature DCs can no longer present newly encountered antigens on their MHC II molecules, and that the main checkpoint for the lack of presentation is not antigen availability. An alternative mechanism for this phenomenon might be down-regulation of MHC II synthesis (2, 5, 7, 8, 34, 35), which would impair formation of new MHC II–peptide complexes in mature DCs. Indeed, MHC II synthesis was drastically down-regulated in DCs matured in vivo by CpG injection, as measured by metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation of MHC II molecules, in the three mouse strains analyzed in this study (Fig. 4). Synthesis of MHC I molecules did not decrease on maturation (data not shown) (5, 7, 8, 34), consistent with maintenance of MHC I presentation in mature DCs (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

Mature DCs down-regulate MHC II synthesis. DCs were purified from the indicated strains of control or CpG-pretreated mice and metabolically labeled with [35S]met/cys for 60 min. MHC II molecules were then immunoprecipitated from equivalent amounts of radiolysate, as determined by TCA precipitation and quantitation of radioactive proteins. The immunoprecipitates were run in a 12.5% SDS/PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. The legend indicates the positions of the MHC II α and β chains, and the p31 (Ii) and p41 (Iip41) splice variants of the MHC II chaperone Ii. The results are representative of multiple experiments.

DC Preactivation Impairs MHC II Presentation in Vivo.

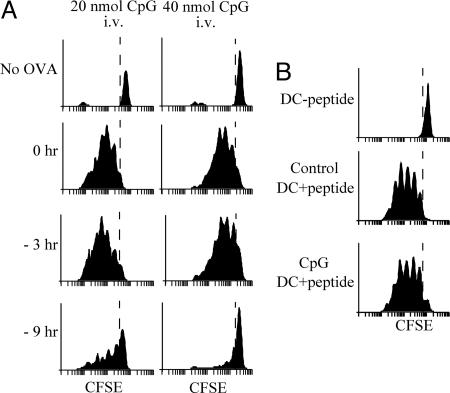

An implication of the effect of DC preactivation on subsequent antigen presentation is that conditions that promote systemic DC maturation may limit the efficacy of vaccination. To test this hypothesis, we compared the responses of OT-II cells in mice inoculated with OVA together with one of two different doses of CpG, with those in mice that first received CpG and were then injected with OVA, 3 or 9 h later. All mice were injected i.v. with CFSE-labeled OT-II cells immediately after the OVA injection, and the proliferation of these T cells in the spleen was determined 2.5 days later. The extent of OT-II proliferation decreased slightly in mice treated with CpG 3 h before the OVA challenge, and was severely impaired in mice that received CpG 9 h before OVA (Fig. 5A). These results show that induction of systemic DC maturation can prevent presentation of subsequently encountered vaccine antigens in vivo. To test whether this immunosuppressed state could be reversed by providing DCs presenting antigen, we purified mature DCs from CpG-pretreated mice and incubated them in vitro with synthetic OVA323–339 peptide. The DCs were washed and injected i.v. in control or CpG-pretreated mice. CFSE-labeled OT-II cells were then inoculated in separate injections. Measurement of OT-II proliferation by FACS 2.5 days later showed that the immunosuppression caused by systemic DC maturation could be reversed by adoptive transfer of DCs presenting the antigen (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, because the transferred DCs were from CpG-pretreated animals, this experiment confirmed that such DCs can activate T cells in vivo, provided they present the appropriate MHC II–peptide complexes.

Fig. 5.

Systemic preactivation of DCs impairs presentation of vaccine antigens in vivo. (A) Mice were treated with 20 or 40 nmol of CpG at the indicated times before receiving 100 μg per mouse of soluble OVA and CFSE-labeled OT-II T cells. Proliferation of OT-II T cells in the spleen was assessed 60 h later. The top profiles correspond to nonimmunized mice. (B) DCs purified from CpG-pretreated mice were incubated in vitro without (−peptide) or with OVA323–356 (+peptide), washed, and injected i.v. into control or CpG-pretreated mice. All mice then received CFSE-labeled OT-II T cells, and T cell proliferation in the spleen was analyzed 60 h later.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that DCs matured in vivo by CpG lose their ability to present newly encountered antigens via MHC II. Animals in which pathogen-associated compounds had caused systemic DC maturation were thus unable to present new antigens such as OVA to CD4 T cells and induce their proliferation. Efficient T cell proliferation in CpG-pretreated mice vaccinated with DCs loaded ex vivo with synthetic peptide antigens indicated that CpG injection had not caused overt suppression of CD4 T cell activation in these mice. Similar effects were induced by injection of other TLR ligands [e.g., LPS or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (data not shown)] and by blood infections with pathogens such as the malaria parasite (data not shown), which also cause systemic DC maturation (27).

We have previously shown that systemic DC preactivation impaired cross-presentation and the stimulation of CD8+ T cell responses against herpes simplex virus and influenza virus, which are probably induced by cross-priming (21). Impairment of cross-presentation of viral antigens was attributed chiefly to down-regulation of phagocytosis, which prevented mature DCs from capturing infected cells. Indeed, mature DCs could present endogenous viral antigens via MHC I if infected (21) (Fig. 3), indicating that their endogenous MHC I presentation pathway was operative. Down-regulation of phagocytosis is also the primary cause of impairment of MHC II presentation of cell-associated antigens by mature DCs (21). However, lack of antigen capture cannot be the main cause of impaired MHC II presentation of viral antigens seen here, because mature DCs efficiently presented these same antigens via the MHC I pathway, indicating synthesis of the antigen by the DCs.

Presentation of soluble antigens such as OVA and HEL was likewise impaired in mature DCs even though these cells still endocytosed and processed this form of antigen. Soluble proteins can be internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis or fluid-phase pinocytosis. One candidate endocytic receptor might be the mannose receptor, which efficiently captures OVA and, in bone marrow-derived DCs, delivers this antigen to specialized compartments for MHC I cross-presentation and away from the MHC II presentation pathway (36). However, this receptor is unlikely to play a major role in the uptake of the antigens assessed in our study. First, HEL is a nonglycosylated protein. Second, the mannose receptor is not expressed in splenic DCs (37), or is only expressed in a subgroup of the CD8+ DC population (36), yet all of the CD8+ DCs, and also the CD8− DCs, capture and present soluble OVA in vivo and in vitro (32, 38). Fluid-phase endocytosis is more likely to be involved in capture of soluble OVA and HEL, and because micropinocytosis remains largely unchanged in mature DCs (3, 4), uptake via this mechanism can explain why the rate of uptake and degradation of OVA was little affected by DC maturation.

Regardless of which specific mechanism is involved, it is clear that lack of endocytosis cannot by itself explain the inability of mature DCs to present newly encountered antigens via the MHC II pathway. The mechanism responsible for this impairment is more likely the down-regulation of MHC II synthesis that accompanies DC maturation, which prevented formation of new MHC II–peptide complexes in mature DCs (2, 5, 7, 8, 34, 35).

The experiments shown here were carried out by using the two major “lymphoid organ-resident” DC populations, namely the CD8+ and CD8− DCs (26). MHC II presentation of antigens captured by phagocytosis or by some C-type lectin receptors is carried out more efficiently by CD8− than by CD8+ DCs, whereas MHC I cross-presentation of these same antigens is carried out almost exclusively by CD8+ DCs (17, 32). This has led to the suggestion that the MHC II antigen presentation machinery is relatively inefficient in CD8+ DCs (17). Our analysis of presentation of soluble HEL, or of the endogenous viral antigen HA, does not support this hypothesis. In line with previous studies (2, 27, 28, 33, 39), our results confirm that overall formation of MHC II–peptide complexes is comparable in CD8− and CD8+ DCs. Therefore, it appears more likely that the difference in presentation of antigens internalized by phagocytosis or C-type lectin receptors between the two DC subsets is caused by differential delivery of antigens captured by these two mechanisms to compartments for MHC II presentation (36). Direct analysis of antigen trafficking will be required to confirm or discard this hypothesis (26). In any case, both lymphoid organ-resident DC types down-regulated MHC II presentation of antigens encountered after maturation.

Our results contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms of immunosuppression associated with blood infections such as sepsis (22) and malaria (23). In most scenarios of infection, down-regulation of antigen presentation in mature DCs should have no deleterious consequences because the number of DCs that respond to a given pathogen is probably small. Therefore, each pathogen encounter probably leaves enough immature DCs ready to respond to subsequent challenges. However, systemic DC maturation induced by sepsis or malaria infection depletes the immune system of DCs capable of responding to new infections and thus causes immunosuppression. Such an effect might contribute to poor vaccination outcomes, and to the prevalence of Burkitt's lymphoma, in malaria-endemic areas (40, 41), the latter thought to be a consequence of compromised control of Epstein–Barr virus infection. We could reverse this effect in our experimental system by injecting the immunocompromised mice with DCs presenting the antigen. Similar approaches, or restoration of antigen presentation by other means, might recover immunocompetence in individuals suffering sepsis or malaria infection. This applies to presentation via MHC II and also to MHC I cross-presentation (21). Importantly, however, approaches that might work to induce MHC I presentation in already mature DCs, such as induction of endogenous expression of the antigen in the DCs, may not work as a strategy to induce MHC II presentation.

Our results also have implications for the design of DC-based prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines. First, vaccination strategies consisting of antigen targeting to DC receptors (14–17) should target immature DCs for maximum efficacy. Second, our observations help to understand why vaccines that combine TLR ligands covalently associated with an antigen are more efficient than those in which the two components are separate, even when administered simultaneously (15, 42). In the latter case, the TLR ligand may reach DCs that have not yet encountered the antigen, inducing their maturation and thus preventing their participation in antigen presentation. Finally, it is important to note that immunotherapeutic approaches (18) consisting of inoculation of DCs that are first induced to mature in vitro, and then transfected with nucleic acids encoding tumor antigens (43), might result in DCs presenting the antigens via MHC I but not via MHC II (44), although evidence to the contrary has been reported as well (45, 46). Lack of induction of helper T cells might lead to poor induction of protective cytotoxic T lymphocyte immune responses (47) or even induce tolerance (48), so caution must be exerted when employing this strategy.

Methods

Mice.

The mice used were 6- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 (H-2b), BALB/c (H-2d), CBA (H-2k), and transgenic strains OT-II (49), act-mOVA (50), HNT (51), and CL4 (52). All mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions following institutional guidelines. Where indicated, mice were injected i.v. in the tail vein with 2.5–50 nmol of synthetic phosphorothioated CpG1668 (GeneWorks, Hindmarsh, Australia) dissolved in PBS.

DC Purification, Culture, and Flow Cytometric Analysis.

DCs were purified from spleens and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in ref. 53. DCs were cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech, Madison, WI) and 0.5 μM CpG1668 (GeneWorks) as described in ref. 27.

Preparation of CFSE-Labeled Transgenic T Cells.

OT-II (I-Ab-restricted anti-OVA323–339), HNT (I-Ad-restricted anti-influenza HA126–138), and CL4 (H-2Kd-restricted anti-influenza HA512–520) T cells were purified from pooled lymph node preparations (subcutaneous and mesenteric) of transgenic mice by depletion of non-CD4 T cells (non-CD8 for CL4 T cells) and were labeled with CFSE as described in refs. 21 and 27. All T cell preparations were determined by flow cytometry as 85–97% pure.

Endocytosis of Soluble OVA:FITC and Processing of DQ-OVA.

Purified DCs were incubated with either the indicated concentrations of OVA conjugated to Alexa 488 (OVA:Ax488) for 45 min or with 1 mg/ml DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at 37 or 4°C for the indicated times, stained with anti-CD11c, washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. To determine the mean linear fluorescence (MLF) values of the samples, it was necessary to discard rare events (<2% of the population) that gave extreme values, so the MLF values were calculated by gating on the area of the plot that contained 98% of the events.

Antigen Presentation to OT-II Cells.

For in vitro assays, purified DCs from control or CpG-pretreated C57BL/6 mice were plated at 5 × 103 cells per well or at the indicated concentrations in V-bottom 96-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) and pulsed for 45 min at 37°C with the indicated concentrations of OVA. Cells were washed and resuspended with 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled OT-II cells. Alternatively, cells were cultured continuously in the presence of 0.5 μg/ml synthetic OVA323–356 peptide (Mimetopes, Melbourne, Australia) and incubated with 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled OT-II cells. DCs from control or CpG-pretreated act-mOVA mice were purified and immediately incubated with 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled OT-II cells. Proliferation of OT-II cells was determined after 60 h of culture as described in refs. 21 and 27. Each determination was performed in duplicate. For the experiments of antigen presentation in vivo, mice were injected i.v. with CpG1668 at varying times before i.v. injection of 100 μg of OVA and 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-II T cells separately in opposite tail veins. Proliferation of OT-II cells in the spleen was determined 60 h later as described in ref. 21.

Formation of I-Ak-HEL48–62 Complexes.

DCs were isolated from control or CpG-pretreated CBA mice and incubated in U-bottom 96-well plates (Falcon, Bedford, MA) with or without 1 mg/ml HEL (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 25 h. Cells were then stained with mAb AW3.18 [anti-I-Ak-HEL48–62 (29)], washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. To determine the MLF values of the samples, it was necessary to discard rare events (<2% of the population) that gave extreme values, so the MLF values were calculated by gating on the area of the plot that contained 98% of the events.

Metabolic Labeling.

Metabolic labeling, immunoprecipitations, and SDS/PAGE analysis were carried out as described in ref. 8. MHC II was immunoprecipitated with a rabbit serum raised against the cytoplasmic portion of I-Aα (54).

Influenza Virus Infection and Proliferation of Virus-Specific T Cells.

DC preparations from control or CpG-pretreated BALB/c mice were washed three times in serum-free RPMI 1640, infected with 5 pfu per cell A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) (Mount Sinai strain; a gift from L. Brown, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia), and purified as described in ref. 21. The indicated numbers of infected DCs were then plated in V-bottom 96-well plates (Costar) with 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled HNT or CL4 transgenic T cells. Proliferation was determined 60 h later. Each determination was performed in duplicate.

Injection of DCs Loaded with OVA Peptide into CpG-Pretreated Mice.

DCs were purified from CpG-pretreated C57BL/6 mice, incubated without or with 1 μg/ml synthetic OVA323–339 for 45 min at 37°C, and washed. A total of 2 × 106 unloaded or peptide-loaded DCs, and 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-II cells, were injected i.v. into opposite tail veins of control mice or mice pretreated with CpG 0, 3, or 9 h earlier. In vivo T cell proliferation was determined 60 h later as described in ref. 21.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Emil Unanue (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) and Raffi Gugasyan (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) for providing the mAb AW3.1; Dr. Lorena Brown (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) for providing influenza virus; and John F. Kupresanin and all of the members of the flow cytometry and animal services facilities at The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (G.T.B., B.S.C., W.R.H., and J.A.V.), the Anti-Cancer Council of Australia (J.A.V.), The Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz Foundation (P.S.), The Wellcome Trust (G.T.B.), The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (G.T.B., B.S.C., and W.R.H.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (J.A.V.), and the University of Melbourne (L.J.Y., N.S.W., A.M., and R.J.L.).

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- MHC II

MHC class II

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- CpG

cytosine-phosphate-guanine-rich oligonucleotide 1668

- OVA

ovalbumin

- HEL

hen egg lysozyme

- CFSE

carboxylfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- HA

hemagglutinin

- MLF

mean linear fluorescence.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0708622104/DC1.

References

- 1.Wilson NS, Villadangos JA. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:241–305. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P, Wilson NS. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrett WS, Chen LM, Kroschewski R, Ebersold M, Turley S, Trombetta S, Galan JE, Mellman I. Cell. 2000;102:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West MA, Prescott AR, Eskelinen EL, Ridley AJ, Watts C. Curr Biol. 2000;10:839–848. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Nature. 1997;388:782–787. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askew D, Chu RS, Krieg AM, Harding CV. J Immunol. 2000;165:6889–6895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villadangos JA, Cardoso M, Steptoe RJ, van Berkel D, Pooley J, Carbone FR, Shortman K. Immunity. 2001;14:739–749. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson NS, El-Sukkari D, Villadangos JA. Blood. 2004;103:2187–2195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin JS, Ebersold M, Pypaert M, Delamarre L, Hartley A, Mellman I. Nature. 2006;444:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature05261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Niel G, Wubbolts R, Ten Broeke T, Buschow SI, Ossendorp FA, Melief CJ, Raposo G, van Balkom BW, Stoorvogel W. Immunity. 2006;25:885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruedl C, Koebel P, Karjalainen K. J Immunol. 2001;166:7178–7182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itano AA, McSorley SJ, Reinhardt RL, Ehst BD, Inguili E, Rudensky AY, Jenkins MK. Immunity. 2003;19:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henri S, Siret C, Machy P, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Leserman L. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1184–1193. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbett AJ, Caminschi I, McKenzie BS, Brady JL, Wright MD, Mottram PL, Hogarth PM, Hodder AN, Zhan Y, Tarlinton DM, et al. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2815–2825. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wille-Reece U, Flynn BJ, Lore K, Koup RA, Kedl RM, Mattapallil JJ, Weiss WR, Roederer M, Seder RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15190–15194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507484102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter RW, Thompson C, Reid DM, Wong SY, Tough DF. J Immunol. 2006;177:2276–2284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, et al. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neill DW, Adams S, Bhardwaj N. Blood. 2004;104:2235–2246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Smedt T, Pajak B, Muraille E, Lespagnard L, Heinen E, De Baetselier P, Urbain J, Leo O, Moser M. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1413–1424. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIlroy D, Troadec C, Grassi F, Samri A, Barrou B, Autran B, Debre P, Feuillard J, Hosmalin A. Blood. 2001;97:3470–3477. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson NS, Behrens GM, Lundie RJ, Smith CM, Waithman J, Young L, Forehan SP, Mount A, Steptoe RJ, Shortman KD, et al. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:165–172. doi: 10.1038/ni1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wykes M, Keighley C, Pinzon-Charry A, Good MF. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabashima K, Banks TA, Ansel KM, Lu TT, Ware CF, Cyster JG. Immunity. 2005;22:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Wicks I, Wu L, O'Keeffe M, Shortman K. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:543–555. doi: 10.1038/nri2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson NS, El-Sukkari D, Belz GT, Smith CM, Steptoe RJ, Heath WR, Shortman K, Villadangos JA. Blood. 2003;102:2187–2194. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veeraswamy RK, Cella M, Colonna M, Unanue ER. J Immunol. 2003;170:5367–5372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dadaglio G, Nelson CA, Deck MB, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Immunity. 1997;6:727–738. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shortman K, Naik SH. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villadangos JA, Heath WR. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnorrer P, Behrens GM, Wilson NS, Pooley JL, Smith CM, El-Sukkari D, Davey G, Kupresanin F, Li M, Maraskovsky E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10729–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manickasingham S, Reis e Sousa C. J Immunol. 2000;165:5027–5034. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rescigno M, Citterio S, Thery C, Rittig M, Medaglini D, Pozzi G, Amigorena S, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5229–5234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeibundGut-Landmann S, Waldburger JM, Reis e Sousa C, Acha-Orbea H, Reith W. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:899–908. doi: 10.1038/ni1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgdorf S, Kautz A, Bohnert V, Knolle PA, Kurts C. Science. 2007;316:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1137971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKenzie EJ, Taylor PR, Stillion RJ, Lucas AD, Harris J, Gordon S, Martinez-Pomares L. J Immunol. 2007;178:4975–4983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pooley JL, Heath WR, Shortman K. J Immunol. 2001;166:5327–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Sukkari D, Wilson NS, Hakansson K, Steptoe RJ, Grubb A, Shortman K, Villadangos JA. J Immunol. 2003;171:5003–5011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson WA, Greenwood BM. Lancet. 1978;1:1328–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittle HC, Brown J, Marsh K, Greenwood BM, Seidelin P, Tighe H, Wedderburn L. Nature. 1984;312:449–450. doi: 10.1038/312449a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yarovinsky F, Kanzler H, Hieny S, Coffman RL, Sher A. Immunity. 2006;25:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilboa E. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1195–1203. doi: 10.1172/JCI31205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morse MA, Lyerly HK, Gilboa E, Thomas E, Nair SK. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2965–2968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonehill A, Heirman C, Tuyaerts S, Michiels A, Breckpot K, Brasseur F, Zhang Y, Van Der Bruggen P, Thielemans K. J Immunol. 2004;172:6649–6657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaft N, Dorrie J, Thumann P, Beck VE, Muller I, Schultz ES, Kampgen E, Dieckmann D, Schuler G. J Immunol. 2005;174:3087–3097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bevan MJ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nri1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janssen EM, Droin NM, Lemmens EE, Pinkoski MJ, Bensinger SJ, Ehst BD, Griffith TS, Green DR, Schoenberger SP. Nature. 2005;434:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature03337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ehst BD, Ingulli E, Jenkins MK. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1355–1362. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6135.2003.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott B, Liblau R, Degermann S, Marconi LA, Ogata L, Caton AJ, McDevitt HO, Lo D. Immunity. 1994;1:73–83. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan DJ, Liblau R, Scott B, Fleck S, McDevitt HO, Sarvetnick N, Lo D, Sherman LA. J Immunol. 1996;157:978–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vremec D, Pooley J, Hochrein H, Wu L, Shortman K. J Immunol. 2000;164:2978–2986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villadangos JA, Riese RJ, Peters C, Chapman HA, Ploegh HL. J Exp Med. 1997;186:549–560. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohmura-Hoshino M, Matsuki Y, Aoki M, Goto E, Mito M, Uematsu M, Kakiuchi T, Hotta H, Ishido S. J Immunol. 2006;177:341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.