Abstract

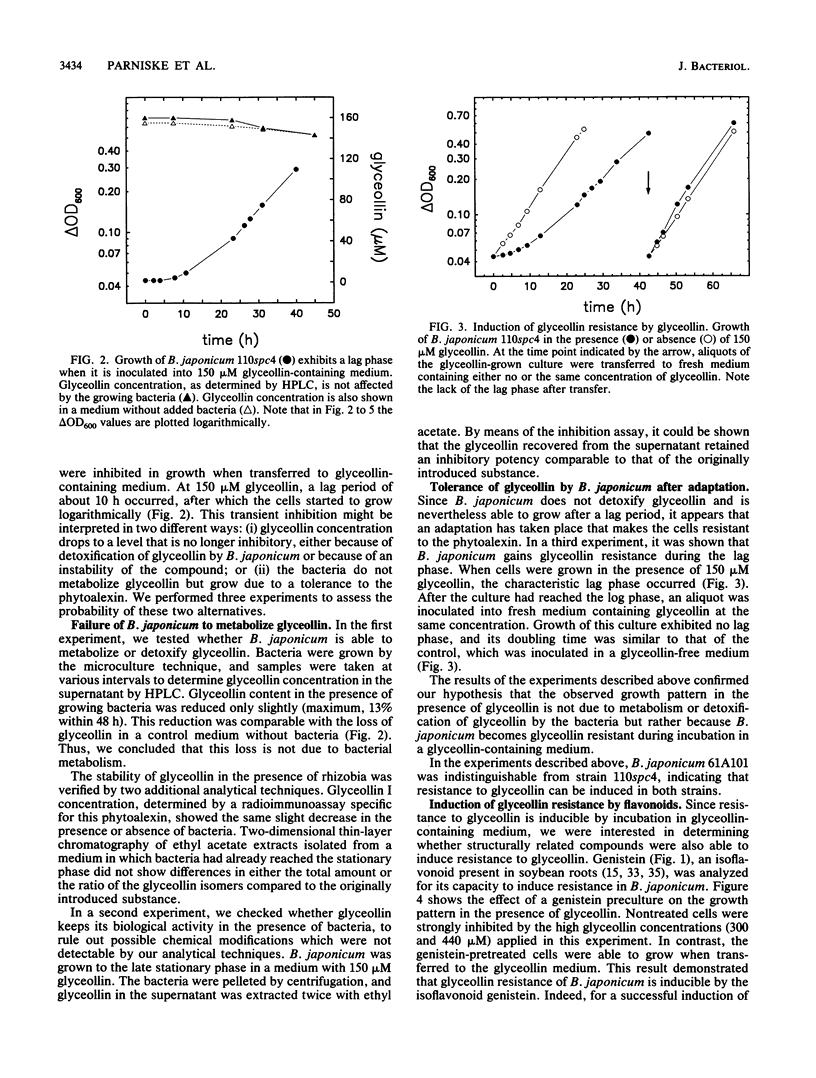

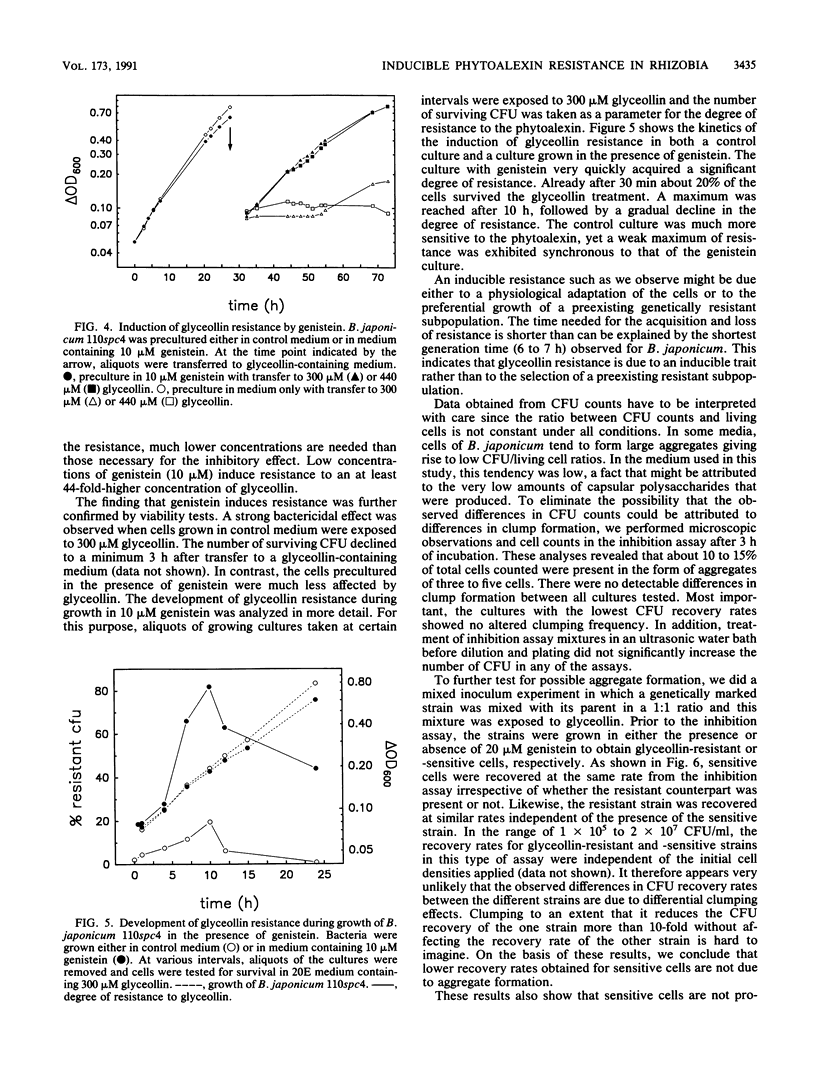

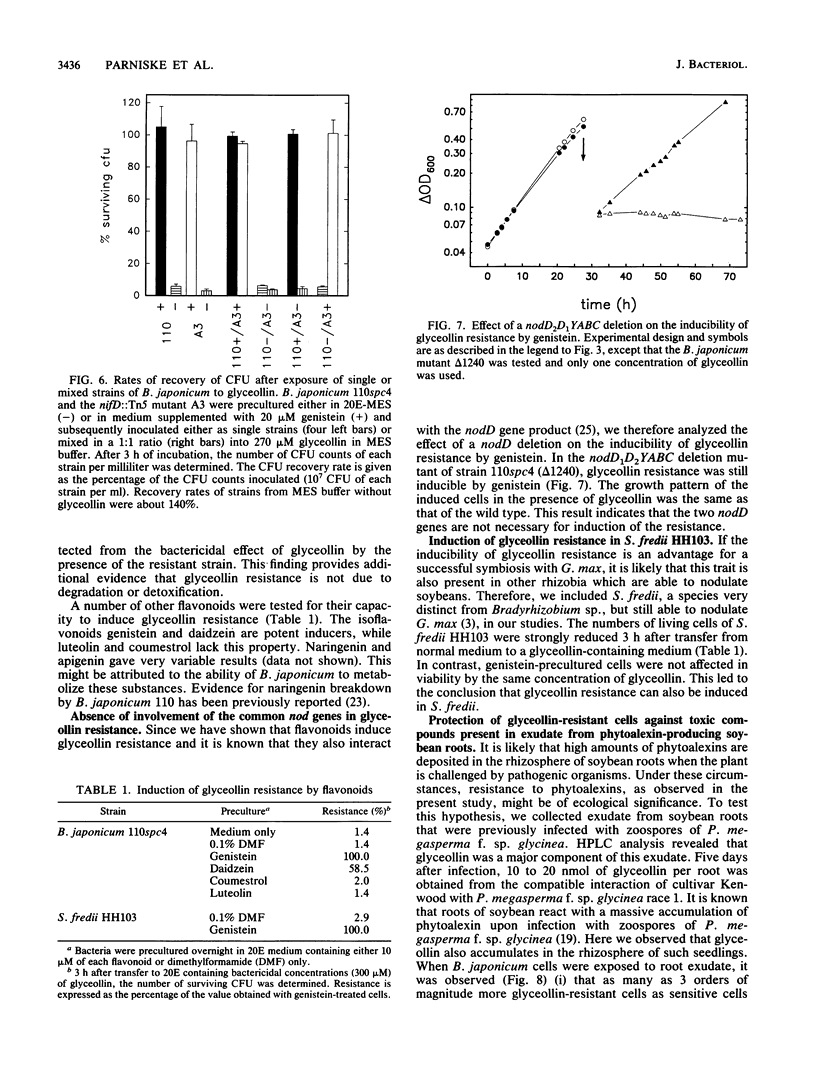

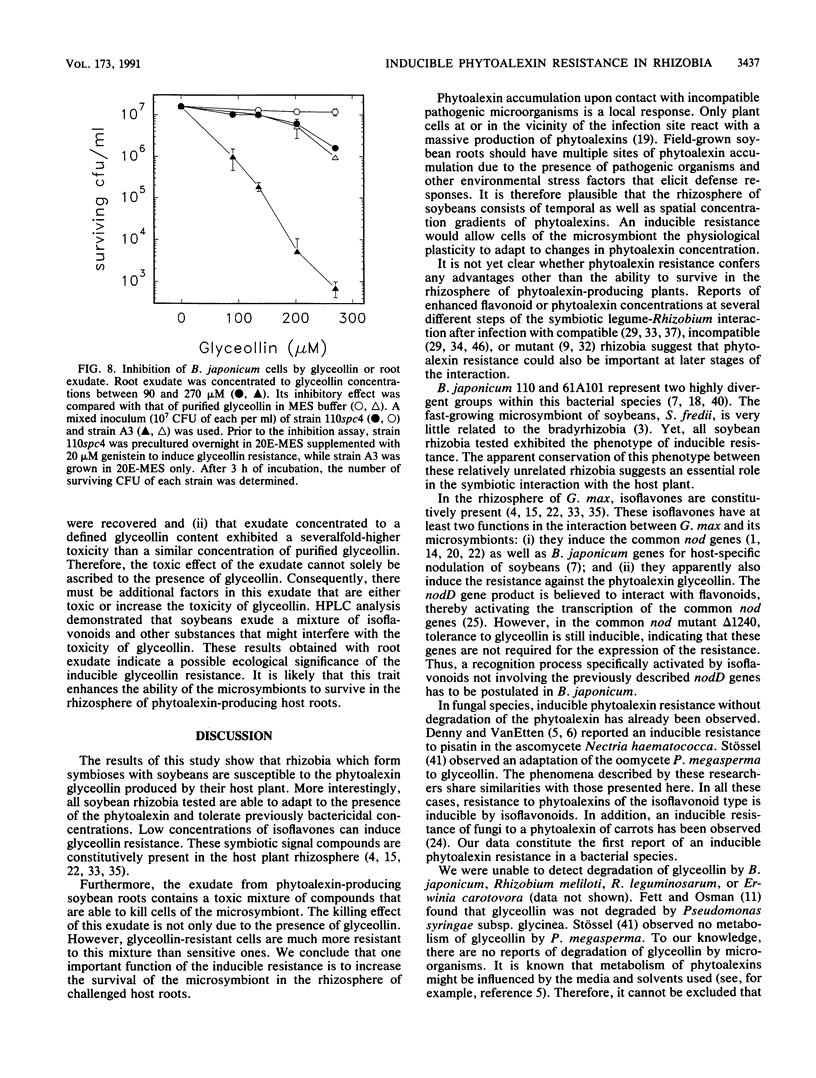

The antibacterial effect of the soybean phytoalexin glyceollin was assayed using a liquid microculture technique. Log-phase cells of Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Sinorhizobium fredii were sensitive to glyceollin. As revealed by growth rates and survival tests, these species were able to tolerate glyceollin after adaptation. Incubation in low concentrations of the isoflavones genistein and daidzein induced resistance to potentially bactericidal concentrations of glyceollin. This inducible resistance is not due to degradation or detoxification of the phytoalexin. The inducible resistance could be detected in B. japonicum 110spc4 and 61A101, representing the two taxonomically divergent groups of this species, as well as in S. fredii HH103, suggesting that this trait is a feature of all soybean-nodulating rhizobia. Glyceollin resistance was also inducible in a nodD1D2YABC deletion mutant of B. japonicum 110spc4, suggesting that there exists another recognition site for flavonoids besides the nodD genes identified so far. Exudate preparations from roots infected with Phytophthora megasperma f. sp. glycinea exhibited a strong bactericidal effect toward glyceollin-sensitive cells of B. japonicum. This killing effect was not solely due to glyceollin since purified glyceollin at concentrations similar to those present in exudate preparations had a much lower toxicity. However, glyceollin-resistant cells were also more resistant to exudate preparations than glyceollin-sensitive cells. Isoflavonoid-inducible resistance must therefore be ascribed an important role for survival of rhizobia in the rhizosphere of soybean roots.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Banfalvi Z., Nieuwkoop A., Schell M., Besl L., Stacey G. Regulation of nod gene expression in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol Gen Genet. 1988 Nov;214(3):420–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00330475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydston R., Paxton J. D., Koeppe D. E. Glyceollin: a site-specific inhibitor of electron transport in isolated soybean mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 1983 May;72(1):151–155. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmane N., Stacey G. Identification of Bradyrhizobium nod genes involved in host-specific nodulation. J Bacteriol. 1989 Jun;171(6):3324–3330. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.6.3324-3330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic S. P., Ridge R. W., Chen H. C., Redmond J. W., Batley M., Rolfe B. G. Induction of pathogenic-like responses in the legume Macroptilium atropurpureum by a transposon-induced mutant of the fast-growing, broad-host-range Rhizobium strain NGR234. J Bacteriol. 1988 Apr;170(4):1848–1857. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1848-1857.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebel J., Grisebach H. Defense strategies of soybean against the fungus Phytophthora megasperma f.sp. glycinea: a molecular analysis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988 Jan;13(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham T. L. Flavonoid and isoflavonoid distribution in developing soybean seedling tissues and in seed and root exudates. Plant Physiol. 1991 Feb;95(2):594–603. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.2.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M. G., Bonhoff A., Grisebach H. Quantitative Localization of the Phytoalexin Glyceollin I in Relation to Fungal Hyphae in Soybean Roots Infected with Phytophthora megasperma f. sp. glycinea. Plant Physiol. 1985 Mar;77(3):591–601. doi: 10.1104/pp.77.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn M., Hennecke H. Conservation of a symbiotic DNA region in soybean root nodule bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Sep;53(9):2253–2255. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2253-2255.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kape R., Parniske M., Werner D. Chemotaxis and nod Gene Activity of Bradyrhizobium japonicum in Response to Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Isoflavonoids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991 Jan;57(1):316–319. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.316-319.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslak R. M., Bookland R., Barkei J., Paaren H. E., Appelbaum E. R. Induction of Bradyrhizobium japonicum common nod genes by isoflavones isolated from Glycine max. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Nov;84(21):7428–7432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosslak R. M., Joshi R. S., Bowen B. A., Paaren H. E., Appelbaum E. R. Strain-Specific Inhibition of nod Gene Induction in Bradyrhizobium japonicum by Flavonoid Compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990 May;56(5):1333–1341. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1333-1341.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S. R. Rhizobium-legume nodulation: life together in the underground. Cell. 1989 Jan 27;56(2):203–214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90893-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985 Mar;49(1):1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst C. E., Biggs D. R. Sensitivity of Rhizobium to selected isoflavonoids. Can J Microbiol. 1980 Apr;26(4):542–545. doi: 10.1139/m80-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recourt K., van Brussel A. A., Driessen A. J., Lugtenberg B. J. Accumulation of a nod gene inducer, the flavonoid naringenin, in the cytoplasmic membrane of Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae is caused by the pH-dependent hydrophobicity of naringenin. J Bacteriol. 1989 Aug;171(8):4370–4377. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4370-4377.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaman H. R., Spaink H. P., Okker R. J., Lugtenberg B. J. Subcellular localization of the nodD gene product in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Bacteriol. 1989 Sep;171(9):4686–4693. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4686-4693.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley J., Brown G. G., Verma D. P. Slow-growing Rhizobium japonicum comprises two highly divergent symbiotic types. J Bacteriol. 1985 Jul;163(1):148–154. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.148-154.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C. P. Rhizobium infection and nodulation: a beneficial plant disease? Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:399–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L. I., Albersheim P. Host-Pathogen Interactions : XXIII. The Mechanism of the Antibacterial Action of Glycinol, a Pterocarpan Phytoalexin Synthesized by Soybeans. Plant Physiol. 1983 Jun;72(2):557–563. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L. I., Hahn M. G., Albersheim P. Host-Pathogen Interactions : XVIII. ISOLATION AND BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF GLYCINOL, A PTEROCARPAN PHYTOALEXIN SYNTHESIZED BY SOYBEANS. Plant Physiol. 1981 Aug;68(2):358–363. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner D., Wilcockson J., Zimmermann E. Adsorption and selection of rhizobia with ion-exchange papers. Arch Microbiol. 1975 Sep 30;105(1):27–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00447108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]