Although many cases of vaginal discharge are not caused by sexually transmitted infections and do not need to be treated, common curable sexually transmitted infections can present with this symptom. Controlling the spread of sexually transmitted infections and HIV are key public health priorities worldwide.1 Recent advances are changing investigation techniques and the management of vaginal discharge. Clinicians need to be aware of emerging epidemiological data, the different presentations of vaginal discharge, and how to approach their management so that the symptom can be treated according to its aetiology (box 1).

Box 1 Causes of vaginal discharge

Non-infective

Physiological

Cervical ectopy

Foreign bodies, such as retained tampon

Vulval dermatitis

Non-sexually transmitted infection

Bacterial vaginosis

Candida infections

Sexually transmitted infection

Chlamydia trachomatis

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Trichomonas vaginalis

What is a physiological (normal) vaginal discharge?

Many women have what they perceive as an abnormal vaginal discharge at some point in their lives, but usually it is just a normal physiological discharge. This is a white or clear, non-offensive discharge that varies with the menstrual cycle. Cervical ectopy can be associated with a mucoid discharge and if symptomatic is widely treated with cryotherapy or diathermy, although evidence to support the effectiveness of these treatments is poor.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched various sources to identify evidence on the aetiology, diagnosis, and treatment of vaginal discharge. Searches of the Cochrane databases, Clinical Evidence, Bandolier, and Medline were undertaken using the keywords “vaginal discharge” and “bacterial vaginosis”, “candidiasis”, “Chlamydia trachomatis”, “gonorrhoea”, “Trichomonas vaginalis”, “nucleic acid amplification techniques”, “polymerase chain reaction”, and “ligase chain reaction”. We consulted generalist and specialist colleagues regarding clinical areas of uncertainty or those lacking evidence.

What non-sexually transmitted infections cause discharge?

Bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis are common; these conditions are thought to by caused by a disturbance of the normal vaginal flora. They are not sexually transmitted and the male partner does not need to be treated. A retrospective study of patients with vaginal discharge in general practice found that most were managed as candidiasis even though bacterial vaginosis is more common.2 Group B Streptococcus is often reported on vaginal swabs, but this organism is not usually thought to cause discharge and only needs treatment in pregnancy.3

Summary points

Vaginal discharge is caused by non-sexually and sexually transmitted infections

Non-sexually transmitted infections may not need treatment, but sexually transmitted ones must be treated and partners notified

Recent research suggests that fewer women with untreated chlamydial infection may develop pelvic inflammatory disease than previously thought—only 1-5.6%

Concurrent infection depends on the population studied

Molecular techniques are more sensitive than culture but are expensive, do not provide antibiotic sensitivities, and results can remain positive after treatment

Self taken vaginal swabs, urine samples, and clinical tampons show comparable results to traditional vaginal specimens

Bacterial vaginosis

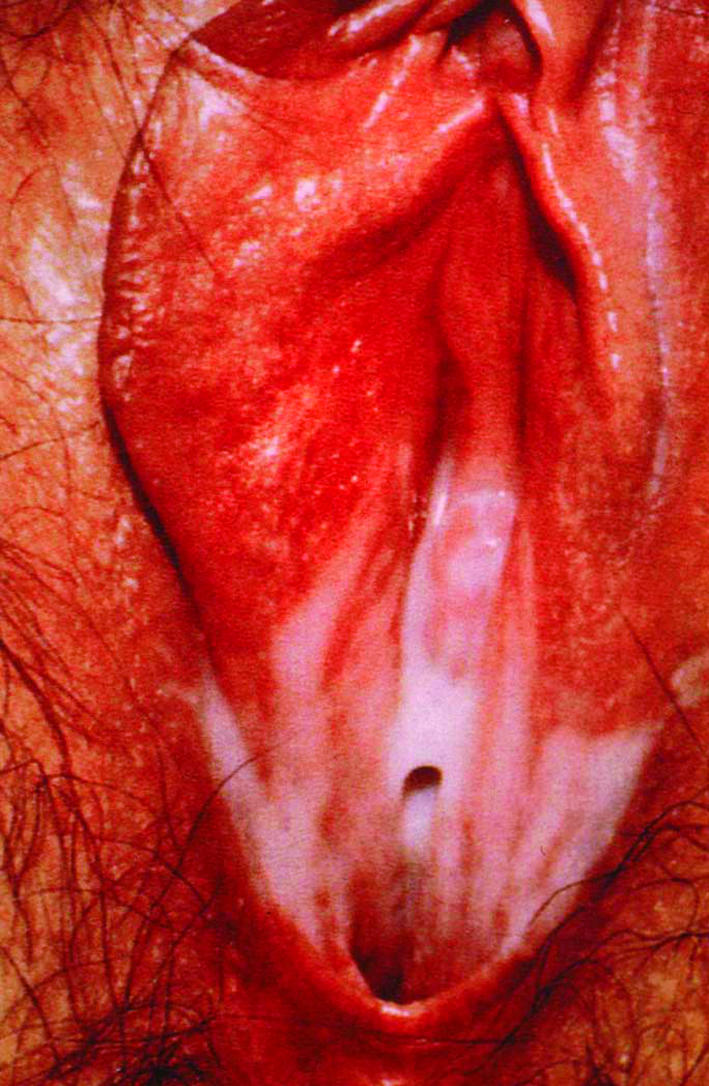

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of infective vaginal discharge,4 5 with a prevalence of 9% in UK general practice.6 It causes profuse and fishy smelling discharge (fig 1) without itch or soreness. This condition is characterised by an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria and occurs and remits spontaneously.7 Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women does not require treatment.4 The condition is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, endometritis after miscarriage, and pelvic inflammatory disease.4

Fig1 Vulval appearance of bacterial vaginosis. Published with permission from McGraw-Hill

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

The prevalence of asymptomatic carriage of Candida in women is 10%.8 Symptoms are vulval itch and soreness and thick white non-offensive discharge (fig 2). There is no evidence that combined oral contraceptives cause candidiasis. Asymptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis does not need treatment.9

Fig2 Appearance of typical vaginal discharge associated with candidiasis on examination with a speculum, courtesy of Herman L Gardner, Houston, Texas, USA

What sexually transmitted infections present with vaginal discharge?

Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis can present with vaginal discharge but may also be asymptomatic. These infections are associated with an increased risk of HIV transmission, especially in the developing world.10 Rates of sexually transmitted infections are rising in the United Kingdom11 and elsewhere, but this observation may be confounded by increased awareness, increased testing, and, importantly, new laboratory techniques.12 Basic epidemiological data about these infections—such as point prevalence, lifetime incidence rate, complication rate, and natural clearance—are scarce for the general population.

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted infection caused by a bacterium in the UK. Around 5-10% of sexually active women under 24 years are infected. Chlamydia can cause a purulent vaginal discharge, but it is asymptomatic in 80% of women.13 It was thought that 10-40% of untreated chlamydial infections will result in pelvic inflammatory disease.13 This has recently been challenged by a large observational study, which reported that only 5.6% of women developed this disease,14 and by a small prospective study that reported an even lower rate of 1%.15 Clearly this has implications for information given to patients and screening programmes.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae may present with a purulent vaginal discharge but is asymptomatic in up to 50% of women. The true prevalence and epidemiology in the general community is not known.16 Gonorrhoea may be complicated by pelvic inflammatory disease.

Trichomonas vaginalis can cause an offensive yellow vaginal discharge, which is often profuse and frothy, along with associated symptoms of vulval itch and soreness, dysuria, and superficial dyspareunia, but many patients are asymptomatic.17 This infection is associated with preterm delivery.5 The true prevalence and epidemiology in the general community is not known.

What about concurrent sexually transmitted infections?

The presence of one sexually transmitted infection makes the presence of other infections more likely, but this depends on the population studied. For example, in a recent large community screened population in the Netherlands, only 0.2% of woman diagnosed with Chlamydia had concurrent gonorrhoea.18 In contrast, up to 40% of women diagnosed with gonorrhoea have a coexisting chlamydial infection.16 Women who have one sexually transmitted infection are likely to have another, including HIV and syphilis, but the role of routine screening for these infections is not established in the literature.

What are the key features from the history?

Features of the discharge such as its timing, colour, consistency, smell, and presence of itch are important in distinguishing between infections. Pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness, and fever should be considered as red flags for pelvic inflammatory disease. Taking a sexual history will help identify patients at high risk of a sexually transmitted infection (young women, those with a recent change of partner, those who have unprotected intercourse, and those who have multiple partners). The need for examination and investigations is usually determined on the basis of such a history. It is important to elicit the patient's “agenda” and explore health beliefs because much social stigma and many lay misconceptions surround sexual health.

What examination is needed, and when?

A vaginal examination using a speculum is often done routinely when a patient presents with vaginal discharge. However, in many situations this is not possible, it is also invasive, and it often does not inform initial management. New sampling techniques may negate the need for vaginal examination in low risk and uncomplicated presentations. Recent General Medical Council guidance on intimate examinations suggests a “chaperone” be offered, even when the examiner is the same sex as the patient. In the management of vaginal discharge, routine bimanual vaginal examination lacks supporting evidence.19 20 and this examination is only indicated if there is concern about pelvic inflammatory disease.

What tests should be done?

Guidance from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV indicates that patients who present with symptoms suggestive of bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis can be treated without sampling.5 Whether or not samples are taken, when they are taken, and what type of samples are taken depends on the resources, the patient, and the clinical setting.

“Triple swabs” (box 2) should be taken—a randomised controlled study of 200 women presenting with vaginal discharge showed that the addition of a high vaginal swab for culture provided a more accurate final diagnosis than the use of microscopy alone.21 If transport of samples is delayed they should be refrigerated.

Box 2 Triple swabs

High vaginal swab to identify bacterial vaginosis, Candida infections, and Trichomonas vaginalis

Endocervical swab in transport medium (charcoal or non-charcoal) to diagnose gonorrhoea

Endocervical swab for a chlamydial DNA amplification test to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis

Vaginal pH testing (using narrow range pH paper) is a quick, cheap, and simple test that can help discriminate between the two most common causes of vaginal discharge—bacterial vaginosis (pH ≥4.5) and vulvovaginal candidiasis (pH <4.5). In one study, pH testing alone had a sensitivity of 73% for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis, but in combination with clinical symptoms this rose to 81%.22

Which new tests are becoming available?

Nucleic acid amplification tests, such as polymerase chain reaction and ligase chain reaction, are molecular biological techniques that amplify DNA and other genetic material. These tests can detect tiny amounts of cells or viruses and are highly sensitive and specific.

A recent systematic review of these tests on urine specimens found high specificity (>95%) and sensitivity (80-93%) for detecting Chlamydia and gonorrhoea (sensitivity was lower for gonococcal infections in women using polymerase chain reaction).23 This increased sensitivity was also demonstrated in a large observational cohort study of women attending a genitourinary medical service, where use of molecular techniques was associated with an increased detection rate of Chlamydia compared with traditional culture (9.9% v 6.1%).12 Commercial assays are available for C trachomatis, T vaginalis, N gonorrhoeae, C albicans, GBS, and herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, and some of these assays give real time rapid results. Molecular based sampling has cost implications and tests remain positive for several weeks after treatment.12 Furthermore, no antibiotic sensitivities are available and a confirmatory culture is needed after a positive molecular test for gonorrhoea.

What is the role of self taken swabs and urine testing?

Molecular tests can use non-traditional samples. Self taken vaginal swabs, urine samples, and clinical tampons have shown comparable results to traditional vaginal specimens.24 25 These methods are more acceptable to patients, and in a large questionnaire study 76% of respondents preferred self taken swabs and 94% stated they would be willing to be tested more often if self taken swabs could be used.26 Such specimens also negate the problems associated with chaperones. The potential for testing using non-clinic based environments is enormous (for example, postal kits), and these techniques are in the process of being validated in clinical practice.

What are the recommended treatments?

Box 3 summarises some of the recommended treatments for individual infections.

Box 3 Management of vaginal infections

Bacterial vaginosis

Metronidazole 2 g as a single oral dose, metronidazole 400-500 mg twice daily for five to seven days, intravaginal clindamycin cream (2%) once daily for seven days, or intravaginal metronidazole gel (0.75%) once daily for five days4

The infection often recurs and acidic vaginal jelly (such as Relact from Kora Healthcare) may reduce relapse rates27

Partner notification not needed

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Vaginal imidazole preparations (such as clotrimazole, econazole, miconazole—various preparations are available including single dose ones), or fluconazole 150 mg orally8

The role of alternative treatments like tea tree oil and yoghurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus have not been evaluated9

Oral versus vaginal treatment depends on preference

Treatment for candidiasis is available over the counter in the UK

Partner notification not needed

Chlamydia trachomatis

Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for seven days (contraindicated in pregnancy), azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose (WHO recommends azithromycin in pregnancy but the British National Formulary advises against its use unless no alternatives are available)13

A test of cure is not indicated13

Partner notification required

Gonorrhoea

Cefixime 400 mg as a single oral dose or ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly as a single dose16

Referral to a genitourinary medical unit is encouraged because of the existence of resistant strains of the organism16

A test of cure is not routinely indicated if an appropriately sensitive antibiotic has been given, symptoms have resolved, and there is no risk of reinfection16

Partner notification required

Trichomonas vaginalis

Metronidazole 2 g orally in a single dose or metronidazole 400-500 mg twice daily for five to seven days17

Partner notification required

Readers should refer to BASHH guidelines, the British National Formulary, and local policies for full treatment options, including treatment in pregnancy

What about resource poor countries?

In countries that lack laboratory services, the World Health Organization promotes the use of “syndromic management” of vaginal discharge.10 Algorithms are used to assess the probability of infections on the basis of history and examination, and patients are treated empirically on this basis. This pragmatic approach has helped reduce the spread of HIV.10

Hygiene advice

Patients should be advised to avoid using local irritants, like perfumed soaps and shower gels, and to be wary of feminine hygiene products such as wipes, powders, and sprays, which may upset the vaginal flora or cause allergic reactions.4 Vaginal douching should be avoided as it is associated with bacterial vaginosis and pelvic inflammatory disease.

What about partner notification?

Partner notification of recent sexual contacts is considered essential both nationally and internationally to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections including HIV. A recent systematic review, however, commented on the poor quality of the available data, but highlighted the need to involve the patient in sharing responsibility. Consider using patients to deliver partner therapy, allowing home sampling for partners, and providing additional information for partners.28 A large randomised controlled trial of nurse led, primary care based partner notification proved this to be feasible, effective, and no more expensive than specialist services.29

When should I refer patients?

Most patients presenting with vaginal discharge will have either a physiological or a non-sexually transmitted infective cause, and these can be managed within primary care. Uncomplicated sexually transmitted infections can be managed in primary care with the support of specialist services, particularly with regard to providing partner notification. Specialist referral should be considered for women with recurrent discharge, pregnant women, or women whose discharge is complicated by pelvic pain. Near patient microscopy, available in many specialist services, is a useful diagnostic tool. Access to sexual and reproductive health services is important, and this is reflected by the location of services within the community and the self referral or drop-in approaches offered by many clinics in the UK.

Additional educational resources

Resources for healthcare professionals

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (www.bashh.org/guidelines.asp)—Series of guidelines on sexual health

Clinical Evidence (www.clinicalevidence.com)—A medical resource for informing treatment decisions and improving patient care

Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care (www.ffprhc.org.uk )—This organisation provides information and a clinical advisory service on sexual health

Medical Foundation for AIDS and Sexual Health (www.medfash.org.uk )—This organisation works with policy makers and health professionals to promote excellence in the prevention and management of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections

Resources for patients

FPA (www.fpa.org.uk/)—Information for professionals and patients. The leaflet “Bodyworks” is particularly useful

Clinical Knowledge Summaries (www.cks.library.nhs.uk/patient_information/browse_all_leaflets)—Evidence based clinical knowledge on common conditions managed in primary and first contact care. The site provides useful information leaflets for patients

Best Treatments (www.besttreatments.co.uk)—Website that rates thousands of health and medical treatments on the basis of how well they work

Contributors: Both authors researched and drafted the sections with which they were most familiar. DS combined the separate sections. Both authors contributed to, approved, and submitted the final version of the manuscript. DS is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Glasier A, Metin Gulmezoglu A, Schmid GP, Garcia Moreno C, Van Look PFA. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. Lancet 2006;368:1595-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Dowd TC, Parker S, Kelly A. Women's experiences of general practitioners' management of their vaginal symptoms. Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:415-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw C, Mason M, Scoular A. Group B streptococcus carriage and vulvovaginal symptoms: causal or casual? A case-control study in a GUM clinic population. Sex Transm Infect 2003;79:246-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay P. National guideline for the management of bacterial vaginosis. Clinical Effectiveness Group. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2006. www.bashh.org/guidelines/2006/bv_final_0706.pdf

- 5.FFPRHC and BASHH Guidance. The management of women of reproductive age attending non-genitourinary medicine settings complaining of vaginal discharge. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2006;32:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson J. Vaginal discharge. In: Walker J, ed. Sexual health in obstetrics and gynaecology 1st ed. London: Remedica, 2003:33-51.

- 7.Wilson J. Managing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels D. Forster national guideline on the management of vulvovaginal candidiasis. G. Clinical Effectiveness group (British Association for Sexual Health and HIV). 2002

- 9.Spence D. Candidiasis (vulvovaginal). Clin Evid 2006;15:2403-18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Sexually transmitted and other reproductive tract infections. 1 Sexually transmitted diseases. 2 HIV infections. 3 Genital diseases, female. 4 Genital diseases, male. 5 Infection. 6 Pregnancy complications, infectious. 7 Rape. 8 Practice guidelines. 9 Developing countries. Geneva: WHO, 2005

- 11.Brown AE, Sadler KE, Tomkins SE, McGarrigle CA, LaMontagne DS, Goldberg D, et al. Recent trends in HIV and other STIs in the United Kingdom: data to the end of 2002. Sex Transm Infect 2004;80:159-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burckhardt F, Warner P, Young H. What is the impact of change in diagnostic test method on surveillance data trends in Chlamydia trachomatis infection? Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:24-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horner PJ, Boag F. National guideline for the management of genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Clinical Effectiveness group. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2006. www.bashh.org/guidelines/2006/chlamydia_0706.pdf

- 14.Low N, Egger M, Sterne JA, Harbord R, Ibrahim F, Lindblom B, et al. Incidence of severe reproductive tract complications associated with diagnosed genital chlamydial infection: the Uppsala women's cohort study. Sex Transm Infect 2006;82:212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morré SA, van den Brule AJC, Rozendaal L, Boeke AJ, Voorhorst FJ, de Blok S, et al. The natural course of asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infections: 45% clearance and no development of clinical PID after one-year follow up. Int J STD AIDS 2002;13(suppl 2):12-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bignell C. National guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Clinical Effectiveness group. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2005. www.bashh.org/guidelines/2005/gc_final_0805.pdf

- 17.Sherrard J. National guideline on the management of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clinical Effectiveness group. British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. 2007. www.bashh.org/guidelines/2007/tv0607.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Van Bergen JE, Spaargaren J, Gotz HM, Veldhuijzen IK, Bindels PJ, Coenen TJ, et al. Should asymptomatic persons be tested during population-based Chlamydia screening also for gonorrhoea or only if chlamydial infection is found? BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blake DR, Fletcher K, Joshi N, Emans SJ. Identification of symptoms that indicate a pelvic examination is necessary to exclude PID in adolescent women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2003;16:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padilla LA, Radosevich DM, Milad MP. Limitations of the pelvic examination for evaluation of the female pelvic organs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2005;88:84-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melville C, Nandwani R, Bigrigg A, McMahon AD. A comparative study of clinical management strategies for vaginal discharge in family planning and genitourinary medicine settings. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2005;31:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thinkhamrop J, Lumbiganon P, Thongkrajai P, Chongsomchai C, Pakarasang M. Vaginal fluid pH as a screening test for vaginitis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1999;66:143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook RL, Hutchison S, Ostergaard L, Braithwaite S, Ness RB. Systematic review: noninvasive testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:914-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrow SC, Smith DW, Harnett GB. The diagnosis of Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, and trichomonas infections by self obtained low vaginal swabs, in remote northern Australian clinical practice Sex Transm Infect 2002;78:278-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaydos CA, Crotchfelt KA, Shah N, Tennant M, Quinn TC, Gaydos JC, et al. Evaluation of dry and wet transported intravaginal swabs in detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in female soldiers by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:758-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernesky MA, Hook EW 3rd, Martin DH, Lane J, Johnson R, Jordan JA, et al. Women find it easy and prefer to collect their own vaginal swabs to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:729-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson JD, Shann SM, Brady SK, Mammen-Tobin AG, Evans AL, Lee RA. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis: the use of maintenance acidic vaginal gel following treatment. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trelle S, Shang A, Nartey L, Cassell JA, Low N. Improved effectiveness of partner notification for patients with sexually transmitted infections: systematic review. BMJ 2007;334:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Low N, McCarthy A, Roberts TE, Huengsberg M, Sanford E, Sterne JAC, et al. Partner notification of chlamydia infection in primary care: randomised controlled trial and analysis of resource use. BMJ 2006;332:14-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]