Abstract

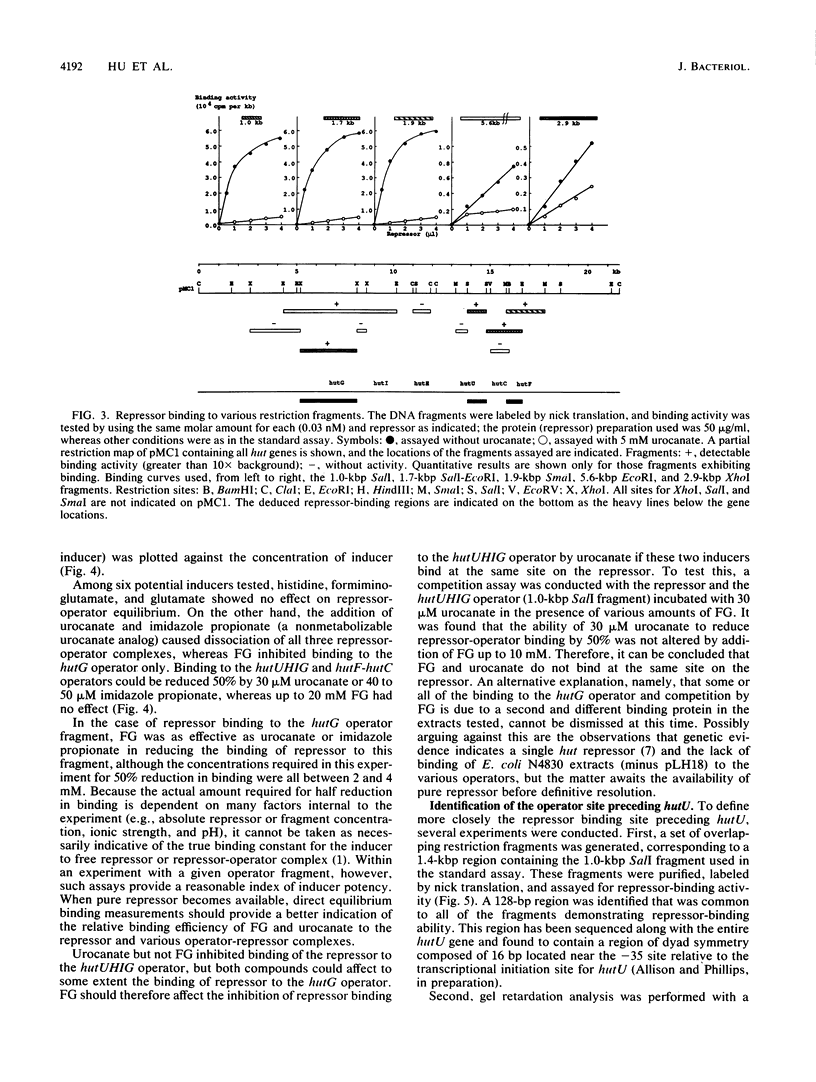

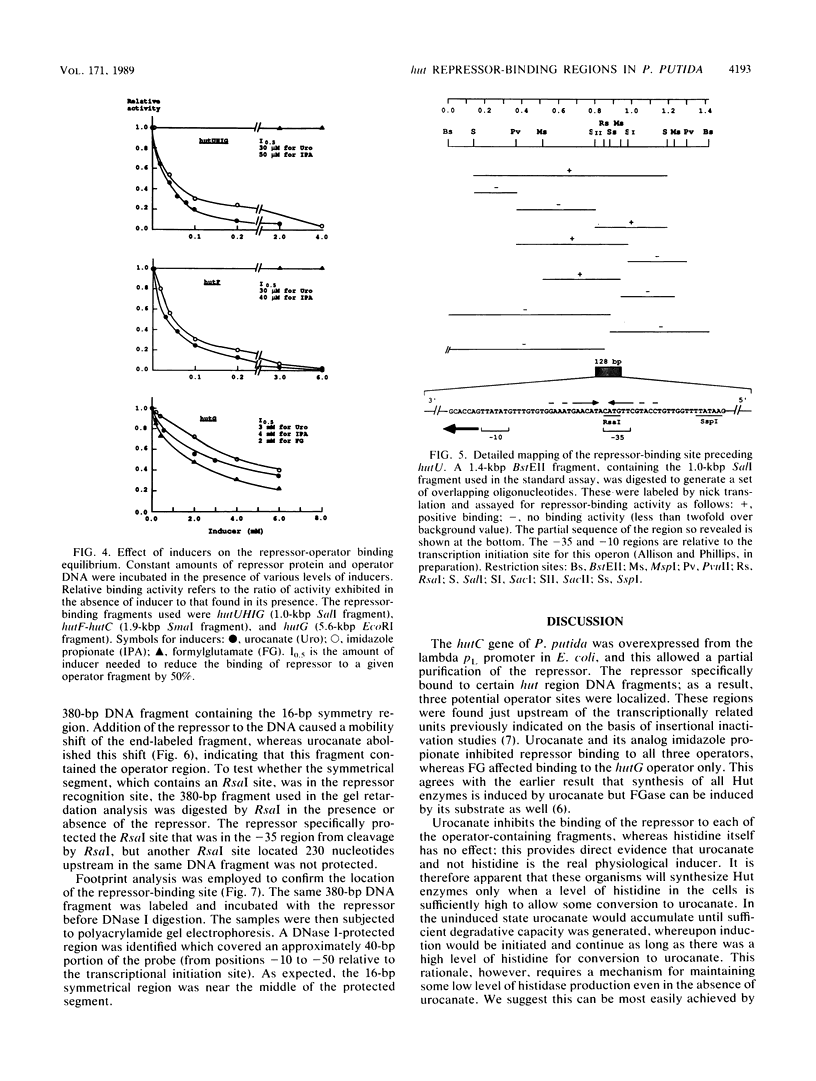

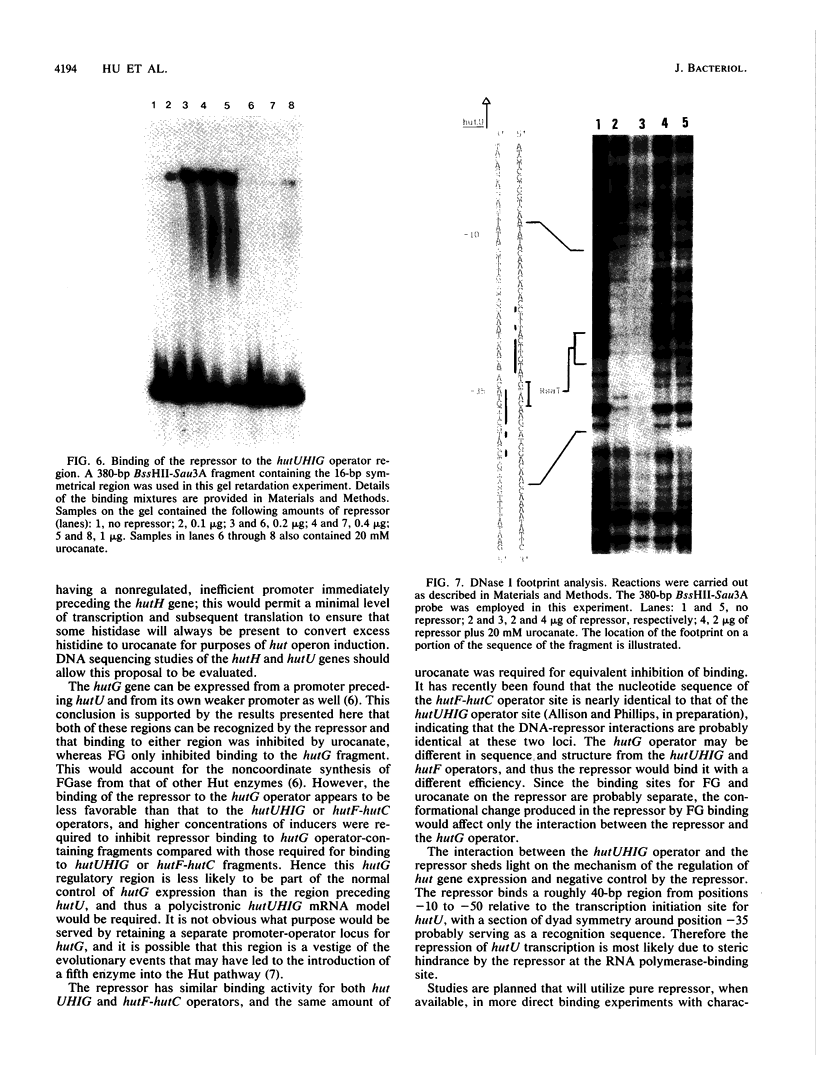

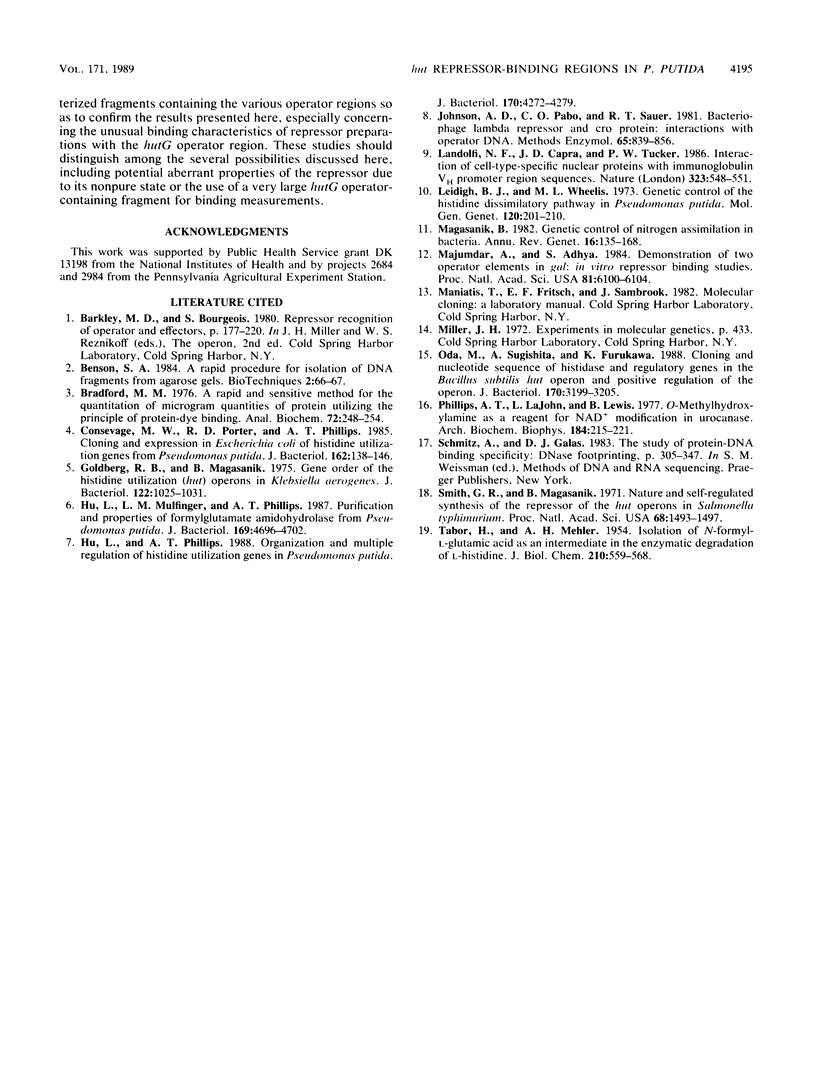

The hutC gene in Pseudomonas putida encodes a repressor protein that negatively regulates the expression of all hut genes. We have overexpressed this cloned hutC gene in Escherichia coli to identify P. putida hut regions that could specifically bind the repressor. Ten restriction fragments, some of which were partially overlapping and spanned the coding portions of the P. putida hut region, were labeled and tested for their ability to recognize repressor in a filter binding assay. This procedure identified three binding sites, thus supporting previous indications that there were multiple operons. A 1.0-kilobase-pair SalI restriction fragment contained the operator region for the hutUHIG operon, whereas a 1.9-kilobase-pair SmaI fragment contained the hutF operator. A 2.9-kilobase-pair XhoI segment appeared to contain the third operator, corresponding to a separate and perhaps little used control region for hutG expression only. The addition of urocanate, the normal inducer, caused dissociation of all operator-repressor complexes, whereas N-formylglutamate, capable of specifically inducing expression of the hutG gene, inhibited binding only of repressor to fragments containing that gene. Formylglutamate did not affect the action of urocanate on the repressor-hutUHIG operator complex, indicating that it binds to a site separate from urocanate on the repressor. DNA footprinting and gel retardation analyses were used to locate more precisely the operator for the hutUHIG operon. A roughly 40-base-pair portion was identified which contained a 16-base-pair region of dyad symmetry located near the transcription initiation site for this operon.

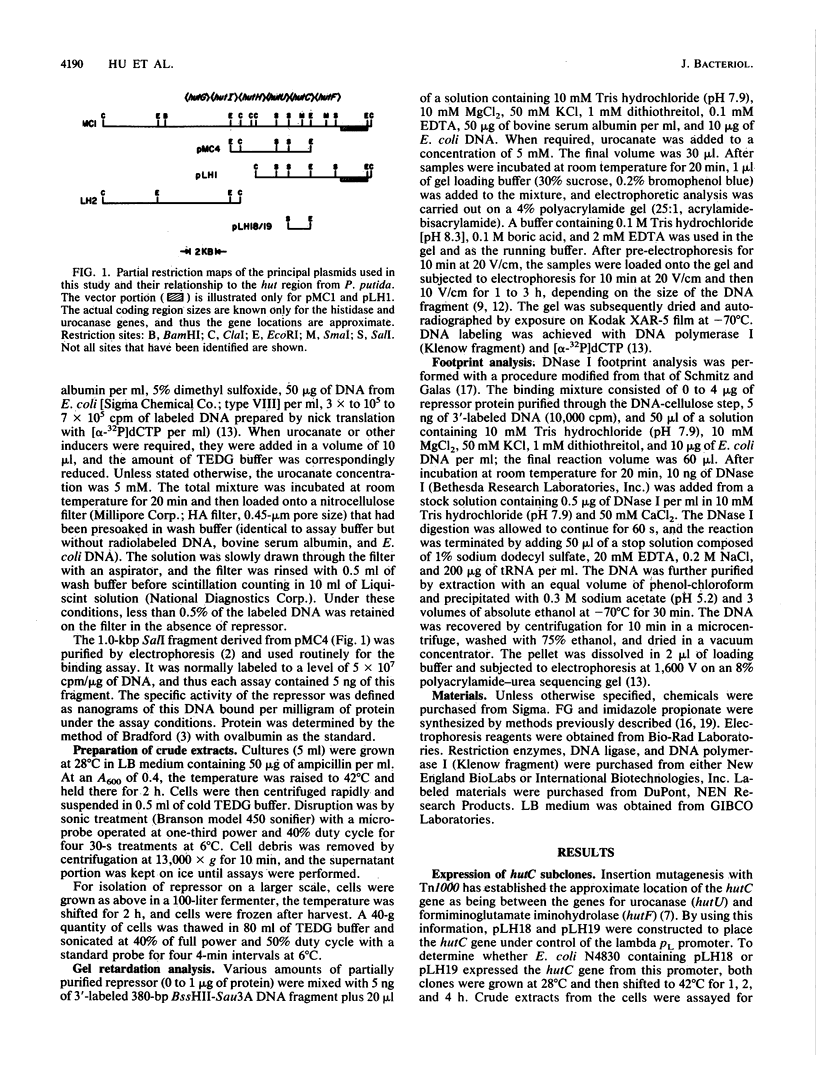

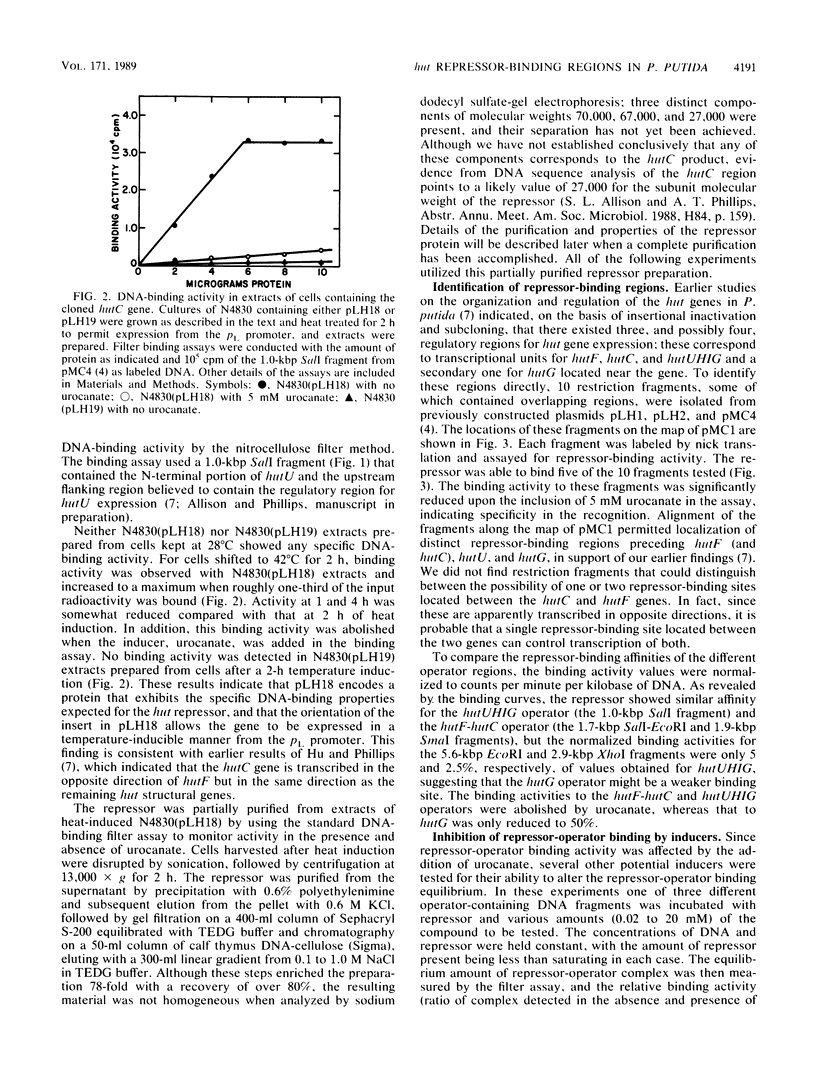

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consevage M. W., Porter R. D., Phillips A. T. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of histidine utilization genes from Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1985 Apr;162(1):138–146. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.138-146.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R. B., Magasanik B. Gene order of the histidine utilization (hut) operons in Klebsiella aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1975 Jun;122(3):1025–1031. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.3.1025-1031.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Mulfinger L. M., Phillips A. T. Purification and properties of formylglutamate amidohydrolase from Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1987 Oct;169(10):4696–4702. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4696-4702.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Phillips A. T. Organization and multiple regulation of histidine utilization genes in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1988 Sep;170(9):4272–4279. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4272-4279.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. D., Pabo C. O., Sauer R. T. Bacteriophage lambda repressor and cro protein: interactions with operator DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):839–856. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolfi N. F., Capra J. D., Tucker P. W. Interaction of cell-type-specific nuclear proteins with immunoglobulin VH promoter region sequences. Nature. 1986 Oct 9;323(6088):548–551. doi: 10.1038/323548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidigh B. J., Wheelis M. L. Genetic control of the histidine dissimilatory pathway in Pseudomonas putida. Mol Gen Genet. 1973 Feb 2;120(3):201–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00267152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magasanik B. Genetic control of nitrogen assimilation in bacteria. Annu Rev Genet. 1982;16:135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.16.120182.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A., Adhya S. Demonstration of two operator elements in gal: in vitro repressor binding studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Oct;81(19):6100–6104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda M., Sugishita A., Furukawa K. Cloning and nucleotide sequences of histidase and regulatory genes in the Bacillus subtilis hut operon and positive regulation of the operon. J Bacteriol. 1988 Jul;170(7):3199–3205. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3199-3205.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips A. T., LaJohn L., Lewis B. O-methylhydroxylamine as a reagent for NAD+ modification in urocanase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977 Nov;184(1):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. R., Magasanik B. Nature and self-regulated synthesis of the repressor of the hut operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Jul;68(7):1493–1497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.7.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TABOR H., MEHLER A. H. Isolation of N-formyl-L-glutamic acid as an intermediate in the enzymatic degradation of L-histidine. J Biol Chem. 1954 Oct;210(2):559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]