Abstract

The Escherichia coli RecBCD helicase–nuclease, a paradigm of complex protein machines, initiates homologous genetic recombination and the repair of broken DNA. Starting at a duplex end, RecBCD unwinds DNA with its fast RecD helicase and slower RecB helicase on complementary strands. Upon encountering a Chi hot spot (5′-GCTGGTGG-3′), the enzyme produces a new 3′ single-strand end and loads RecA protein onto it, but how Chi regulates RecBCD is unknown. We report a new class of mutant RecBCD enzymes that cut DNA at novel positions that depend on the DNA substrate length and that are strictly correlated with the RecB:RecD helicase rates. We conclude that in the mutant enzymes when RecD reaches the DNA end, it signals RecB’s nuclease domain to cut the DNA. As predicted by this interpretation, the mutant enzymes cut closer to the entry point on DNA when unwinding is blocked by another RecBCD molecule traveling in the opposite direction. Furthermore, when RecD is slowed by a mutation altering its ATPase site such that RecB reaches the DNA end before RecD does, the length-dependent cuts are abolished. These observations lead us to hypothesize that, in wild-type RecBCD enzyme, Chi is recognized by RecC, which then signals RecD to stop, which in turn signals RecB to cut the DNA and load RecA. We discuss support for this “signal cascade” hypothesis and tests of it. Intersubunit signaling may regulate other complex protein machines.

[Keywords: Homologous recombination, E. coli, RecBCD enzyme, Chi sites, complex protein machines]

Multistep processes in living cells, such as replication, transcription, and genetic recombination, are often carried out by complex protein “machines” (Alberts 1998). The multiple activities of each machine must be properly regulated for the process to be successful, but the basis of the regulation is in many cases unclear. We present here experimental results leading to a new hypothesis for how one such machine, the RecBCD enzyme of Escherichia coli, is regulated by Chi, a special nucleotide sequence in the DNA on which RecBCD acts during genetic recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs).

The faithful repair of DSBs is crucial for living cells. Failure to repair such breaks can result in the loss of genetic information, and incorrect repair can yield deleterious genome rearrangements. Repair using homologous but genetically different DNA as a template can produce genetic recombinants, thereby increasing genetic diversity and aiding evolution. Recombination thus provides both short-term and long-term benefits to living organisms.

Recombination is a complex process that requires multiple proteins and enzymatic activities. At the molecular level, one of the best understood paradigms is the major (RecBCD) pathway of DSB repair and recombination in E. coli. Essential for this pathway is the RecBCD enzyme, a protein machine with multiple activities on DNA that promote the initial stages of recombination (Smith 2001). These multiple activities are regulated by Chi sites, 5′-GCTGGTGG-3′, which are hot spots of recombination by the RecBCD pathway (Stahl and Stahl 1977). The physical basis of Chi’s regulation of RecBCD is, however, unknown. Beginning at a double-strand (ds) end in broken DNA, RecBCD rapidly unwinds DNA with its fast RecD helicase moving on the 5′-ended strand and slower RecB helicase moving on the 3′-ended strand (Taylor and Smith 2003). A single-stranded (ss) loop thus accumulates on the 3′-ended strand and grows as the reaction proceeds (Fig. 1A,B; see also Fig. 3A, below).

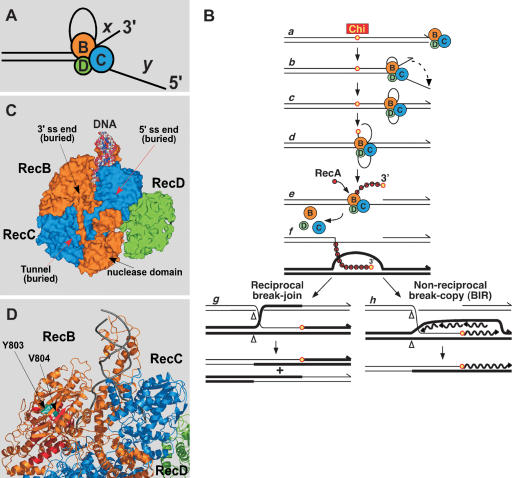

Figure 1.

DNA unwinding by RecBCD enzyme and structure of the enzyme bound to a dsDNA end. The RecB subunit is orange, RecC is blue, and RecD is green. (A) Loop–tail structure formed during DNA unwinding by RecBCD. The lengths of the short (x) and long (y) tails are proportional to the rates of the slower (RecB) and faster (RecD) helicases, respectively (Taylor and Smith 2003). See Figure 3 for examples of electron micrographs of such structures. (B) Model for Chi-stimulated recombination. RecBCD binds a duplex DNA end (a) and unwinds the DNA with the formation of a loop–tail structure (b). (c) The loop and tails enlarge as RecBCD unwinds; the tails can anneal to form a twin-loop structure. Upon encountering Chi, the enzyme cuts the top strand (d) and loads RecA onto the 3′-ended strand (e). (f) The RecA-ssDNA filament forms a D-loop with a homologous duplex. (g) The DNA loop can be cut, with the formation of a Holliday junction, which can be resolved into crossover-type recombinants. (h) Alternatively, the D-loop can prime DNA synthesis, with the formation of a replication fork and a break-induced recombinant (BIR). For discussion of alternative models see Amundsen and Smith (2007) (adapted with permission from the Annual Review of Genetics, Volume 35 © 2001 by Annual Reviews, http://www.annualreviews.org) and Smith (2001) (adapted with permission), from which this figure is adapted. (C) Surface representation of RecBCD-dsDNA complex. The four terminal base pairs of DNA are unwound, and the 3′ end lies within RecB. During unwinding, this strand is postulated to pass through a tunnel in RecB and RecC on its way to the nuclease domain of RecB. Chi is postulated to be recognized by parts of the tunnel in RecC (red arrow). The 5′ end of the DNA lies within RecC and extends toward an unordered part of RecD (amino acids 245–255) lying behind the surface shown. Data from Singleton et al. (2004). (D) Ribbon representation of part of the RecBCD-dsDNA complex. Helicase motifs are in red. The RecB α-helix composed of residues 785–807 contains the conserved motif VI common to helicases and the amino acid substitutions Y803H and V804E described here. Data from Singleton et al. (2004).

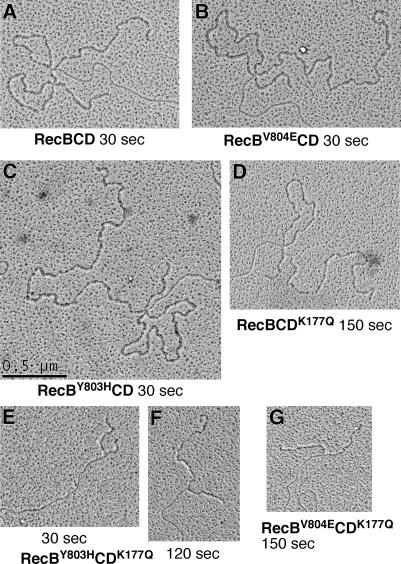

Figure 3.

Mutant RecBCD enzymes make ss loop–tail structures during unwinding similar to those of wild-type RecBCD enzyme. Phage λ DNA was reacted with the indicated enzymes for the stated time, fixed, and examined by EM. ssDNA is bound by SSB protein and appears thicker than dsDNA. Bar is 0.5 μm (∼1.4 kb of dsDNA; ∼4.8 kb of ssDNA) and applies to all panels. For G, the substrate was cut with a restriction enzyme to produce a blunt end.

When RecBCD encounters Chi from the right, as written here, the activities of the enzyme change dramatically. In reactions with excess ATP over Mg2+ ions, the enzyme’s exonuclease activity is low, but its endonuclease activity makes, at high frequency, a ss nick a few nucleotides to the 3′ side of the Chi sequence (Taylor et al. 1985); subsequently, the three subunits disassemble, perhaps at the end of the DNA, and the enzyme remains inactive (Taylor and Smith 1999). In reactions with excess Mg2+ ions over ATP, RecBCD’s exonuclease activity is high, and the enzyme degrades the 3′-ended strand up to Chi (Dixon and Kowalczykowski 1993), nicks the complementary strand (Taylor and Smith 1995b), and then degrades the 5′-ended strand during continued unwinding (Anderson and Kowalczykowski 1997a). At least under this condition, the enzyme begins to load RecA protein onto the 3′-ended strand to the left (“downstream”) of Chi (Anderson and Kowalczykowski 1997b), and the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-RecA filament undergoes strand exchange with a homologous duplex (Dixon and Kowalczykowski 1991). This joint molecule has been postulated to form recombinants by a break-copy scheme (break-induced replication) or by formation and resolution of a Holliday junction (Fig. 1B; Smith 1991).

Crucial to the production of recombinants is the alteration of RecBCD’s activities at and by Chi. The stimulation of recombination by Chi can be up to 30-fold (Stahl and Stahl 1977; Schultz et al. 1983), and recBCD mutants specifically lacking the ability to respond to Chi have reduced recombination proficiency (Schultz et al. 1983; Lundblad et al. 1984). Two classes of mutants lacking Chi hot spot activity have mutations in recC (see Discussion). The amino acids altered in these mutants (Arnold et al. 2000; S.K. Amundsen, unpubl.) line part of a tunnel in the structure of RecBCD cocrystallized with hairpin DNA (Fig. 1C,D). It has been postulated that RecC recognizes Chi as the 3′-ended strand moves from the RecB helicase domain through the tunnel in RecC on its way to the nuclease domain of RecB (Singleton et al. 2004). The steps between Chi recognition and alteration of the nuclease and RecA loading activities are unknown. We describe here a novel class of recB mutant enzymes whose properties indicate that the RecD subunit signals the RecB subunit to cut DNA. These observations lead us to propose a new hypothesis for the regulation of wild-type RecBCD by Chi: a cascade of intersubunit signals from Chi–RecC to RecD to RecB.

Results

Isolation of a novel class of Rec− Nuc+ recBCD mutants

Previous studies of recBCD mutants that lack some but not all RecBCD activities have helped to elucidate how Chi regulates RecBCD enzyme (e.g., Schultz et al. 1983; Lundblad et al. 1984; Amundsen et al. 1990, 2002; Yu et al. 1998b; Amundsen and Smith 2007). To find additional novel mutants, we targeted mutations in DNA encoding the C-terminal 381 amino acids, residues 800–1180, of RecB. This region contains the nuclease and RecA loading domains (Yu et al. 1998b; Spies and Kowalczykowski 2006), two activities altered by Chi. Using a mutagenic PCR and colony-screening procedure, we found 11 isolates that were recombination deficient (Rec−) in Hfr crosses but retained RecBCD exonuclease activity (Nuc+) as indicated by resistance to phage infections (see below; Schultz et al. 1983) or by assay of cell-free extracts (S.K. Amundsen, unpubl.). Each isolate contained two to 10 missense mutations, or 57 mutations in all. Twelve of these mutations were clustered in codons 800–810, of which five were in codon Y803 and two in codon V804. For further analysis, we made single codon mutations, each of which was among the initial 57 mutations, to create two new alleles: recB2732 (Y803H) and recB2734 (V804E). These altered amino acids are in the conserved helicase motif VI of RecB (Fig. 1D; see Discussion). The cellular phenotypes and enzymatic activities in extracts of these mutants were similar to those of the original isolates containing the corresponding mutations. The data presented here were obtained with the single codon mutations.

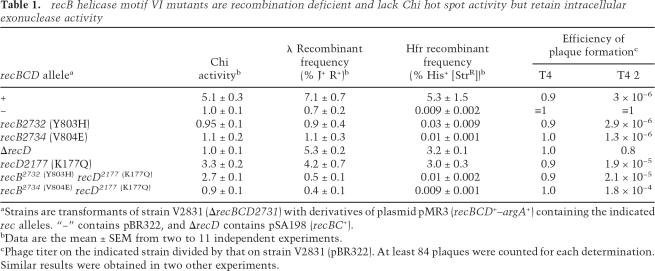

The two new mutants were nearly as Rec− as strains with a ΔrecBCD-null allele. In Hfr crosses, the recombination proficiency of V804E was reduced by a factor of ∼500, like ΔrecBCD, and that of Y803H by a factor of ∼200 (Table 1). In phage λ crosses, in which recombination is less dependent on RecBCD (Stahl and Stahl 1977), the proficiencies were reduced by a factor of ∼7, similar to that of the ΔrecBCD null. In these λ crosses, we measured Chi hot spot activity, the ratio of the recombinant frequency in an interval with Chi to that in the same interval without Chi (Stahl and Stahl 1977). recBCD+ cells gave a Chi activity of 5.3, whereas a recBCD-null mutant gave no Chi activity (ratio of 1), as reported previously (Stahl and Stahl 1977). Like recBCD-null mutants, the new mutants lacked detectable Chi activity (i.e., they were Rec− Chi−) (Table 1).

Table 1.

recB helicase motif VI mutants are recombination deficient and lack Chi hot spot activity but retain intracellular exonuclease activity

aStrains are transformants of strain V2831 (ΔrecBCD2731) with derivatives of plasmid pMR3 (recBCD+–argA+) containing the indicated rec alleles. “−” contains pBR322, and ΔrecD contains pSA198 (recBC+).

bData are the mean ± SEM from two to 11 independent experiments.

cPhage titer on the indicated strain divided by that on strain V2831 (pBR322). At least 84 plaques were counted for each determination. Similar results were obtained in two other experiments.

Two assays indicated that the mutants retained RecBCD exonuclease activity. This activity degrades the DNA of phage T4 lacking the gene 2 protein, which is thought to bind to the ends of the linear DNA in the virion and thereby protect the DNA from RecBCD exonuclease upon injection into an E. coli cell (Oliver and Goldberg 1977). T4 gene 2 mutant phage formed plaques with the same low efficiency (∼10−6) on the new mutants as on recBCD+ cells (Table 1) but formed plaques with near unit efficiency on previously isolated mutants lacking RecBCD exonuclease (ΔrecBCD or ΔrecD).

We next tested the exonuclease activity of RecBCD enzymes purified from the mutants. As expected from the resistance of the mutants to T4 gene 2 mutant phage (Table 1), the mutant enzymes had nearly wild-type levels of ATP-dependent ds exonuclease activity (Table 2), the hallmark of RecBCD enzyme (Smith 1990). We noted, however, that at very low ATP concentration (25 μM), the enzymes had little ds exonuclease activity (Supplementary Fig. S1). Half maximal ds exonuclease activity required ∼0.5–2 mM ATP (Supplementary Fig. S1), closer to the intracellular ATP concentration of ∼3 mM than the standard assay concentration of 25 μM (Eichler and Lehman 1977). The ATP-dependent ssDNA exonuclease activity of the mutant enzymes, compared with that of the wild-type enzyme, was indistinguishable at low ATP concentration (A.F. Taylor, unpubl.) and similar at high ATP concentration (Table 2). Thus, these mutants are Rec− Nuc+ Chi− and may have alterations in Chi’s regulation of RecBCD enzyme.

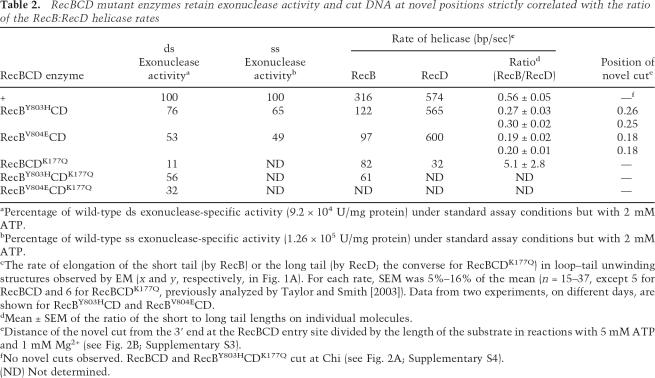

Table 2.

RecBCD mutant enzymes retain exonuclease activity and cut DNA at novel positions strictly correlated with the ratio of the RecB:RecD helicase rates

aPercentage of wild-type ds exonuclease-specific activity (9.2 × 104 U/mg protein) under standard assay conditions but with 2 mM ATP.

bPercentage of wild-type ss exonuclease-specific activity (1.26 × 105 U/mg protein) under standard assay conditions but with 2 mM ATP.

cThe rate of elongation of the short tail (by RecB) or the long tail (by RecD; the converse for RecBCDK177Q) in loop–tail unwinding structures observed by EM (x and y, respectively, in Fig. 1A). For each rate, SEM was 5%–16% of the mean (n = 15–37, except 5 for RecBCD and 6 for RecBCDK177Q, previously analyzed by Taylor and Smith [2003]). Data from two experiments, on different days, are shown for RecBY803HCD and RecBV804ECD.

dMean ± SEM of the ratio of the short to long tail lengths on individual molecules.

eDistance of the novel cut from the 3′ end at the RecBCD entry site divided by the length of the substrate in reactions with 5 mM ATP and 1 mM Mg2+ (see Fig. 2B; Supplementary S3).

fNo novel cuts observed. RecBCD and RecBY803HCDK177Q cut at Chi (see Fig. 2A; Supplementary S4).

(ND) Not determined.

Mutant RecBCD enzymes cut DNA at a position dependent on the DNA substrate length

Wild-type RecBCD enzyme cuts DNA a few nucleotides to the 3′ side of the Chi sequence 5′-GCTGGTGG-3′ (Taylor et al. 1985). When we tested the mutant enzymes for this activity, we observed that they failed to cut at Chi (Fig. 2A), as expected from the lack of Chi hot spot activity in the mutants (Table 1). Instead, each mutant enzyme cut at a novel position, different for each mutant enzyme (Fig. 2A). Remarkably, these novel positions depended on the length of the DNA substrate. Eight substrates, each with the same 5′-labeled end and ranging in length from 1.1 kb to 4.4 kb, were made and reacted with each enzyme. The lengths of the novel 5′-labeled products were determined by gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. S2).

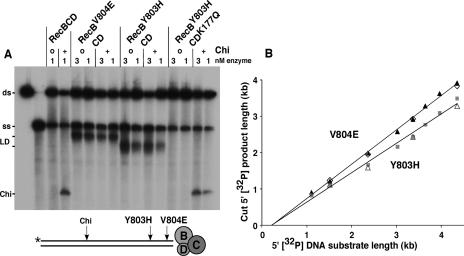

Figure 2.

Mutant RecBCD enzymes cut DNA at novel positions that depend on the length of the DNA substrate. (A) Autoradiograph of an agarose gel for analysis of RecBCD reaction products. DNA substrates (4 nM) with (+) or without (o) Chi and 5′-end-labeled with 32P as diagrammed below the gel were reacted with the indicated enzymes for 2 min and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Note that the RecDK177Q alteration, which slows the RecD helicase (Taylor and Smith 2003), blocks cutting by the Y803H enzyme at the novel length-dependent position but allows cutting at Chi (see also Supplementary Fig. S4). The two left-most lanes contain native and boiled substrate, respectively. (ds) Double-stranded substrate; (ss), single-stranded (boiled) DNA; (LD) length-dependent cut products; (Chi) products cut at Chi. (B) The length of the 5′ [32P] product (p) is a linear function of the length of the substrate (s). Data are from experiments with substrates having a common 5′-labeled end and different lengths (Supplementary Fig. S2). Experiment 1 (open symbols) used four substrates, and experiment 2 (closed symbols) used eight. The linear regression lines are p = 0.94s − 0.20 for V804E (r2 = 0.997) and p = 0.81s − 0.16 for Y803H (r2 = 0.992). Similar results were obtained (A.F. Taylor, unpubl.) when RecBCD entry was limited to the unlabeled end by 3′ ss resection of the other end (Taylor et al. 1985).

The results of these experiments showed that the length of the product fragment was a linear function of the length of the substrate for each mutant (Fig. 2B). Linear regression of the length of the product vs. the length of the substrate gave a straight line with a slope of 0.81 for the Y803H enzyme and 0.94 for the V804E enzyme. Similar results were obtained with substrates whose nucleotide sequence was a circular permutation of that in Figure 2B, confirming that the novel cuts are not sequence dependent (A.F. Taylor, unpubl.). Our interpretation of these results will be clear after the next section.

Ratio of RecB:RecD helicase rates strictly correlates with the position of DNA cutting

As it unwinds DNA, wild-type RecBCD forms two ssDNA tails and a ssDNA loop that moves along the DNA and grows as the reaction proceeds (Fig. 1A; Taylor and Smith 1980), a consequence of RecB moving more slowly on the 3′-ended strand than RecD moves on the 5′-ended strand (Taylor and Smith 2003). The ratio of the lengths of the short and long tails is the ratio of the rates of RecB and RecD movement on their respective strands (Fig. 1A, x/y). To determine if these rates were altered in the recB mutants, we examined by electron microscopy (EM) DNA molecules partially unwound by the wild-type or mutant enzymes (Fig. 3). The rate of elongation of the long tail was not significantly different in the mutants or wild type, indicating that the RecD helicase rate was not detectably altered in the mutants (Table 2). The rate of elongation of the short tail by the mutants was, however, markedly less than that by the wild type, indicating that the mutant RecB helicases moved at only 39% (Y803H) or 31% (V804E) of the rate of wild-type RecB. The ratio of the rates of elongation of the short and long tails (i.e., the RecB:RecD helicase rates, x/y), was 0.28 for Y803H and 0.19 for V804E, compared with 0.56 for wild-type RecBCD.

To compare directly the position of the novel cuts and the rates of unwinding, we had to alter the [Mg2+], since the somewhat higher [Mg2+] used to determine the positions of the cuts in Figure 2 allowed some DNA degradation by RecBCD and hence few intact DNA molecules for the EM analysis. The positions of the cuts changed with [Mg2+]: The cuts were slightly farther from the entry point at lower [Mg2+] (Supplementary Fig. S3), likely a reflection of the differential effects of Mg2+ on the RecB and RecD helicase rates (Spies et al. 2005). Under reaction conditions identical to those used in the EM analysis, with 1 mM Mg2+, the position of the cuts, as a fraction of the lengths of the DNA substrates, was 0.26 for Y803H and 0.18 for V804E (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S3). For each mutant enzyme, this position was indistinguishable from the independently determined ratio of the RecB:RecD helicase rates (x/y), 0.28 for Y803H and 0.19 for V804E (Table 2).

From the two sets of data above, we conclude that the mutant enzymes cut the DNA when RecD reaches the end of the substrate strand on which it travels. At that moment, RecB, with the nuclease domain, would be a fraction of the distance along the other strand, determined by the ratio x/y, and would cut at that position (Fig. 1A). With the observations below, we infer that in these mutants, when RecD stops unwinding, it signals RecB to cut the DNA.

Collision of RecBCD enzymes on DNA changes the position of the novel cuts

When two wild-type RecBCD enzyme molecules act on one DNA substrate, with one enzyme entering from each end, the enzymes collide near the middle of the molecule and cut the DNA there (Dixon and Kowalczykowski 1993). This situation occurs most often at high [RecBCD] relative to [DNA]. We used such collisions to stop the mutant RecBCD enzymes half-way along the DNA. As reported previously, we observed that wild-type RecBCD frequently cut near the middle of the DNA substrate at high concentration, when two enzyme molecules can come from each end, but infrequently at low concentration, when only one enzyme molecule is present on the DNA (Fig. 4). Instead, at low concentration, wild-type RecBCD cut at Chi, which was located beyond the mid-point as RecBCD approached Chi in the active orientation.

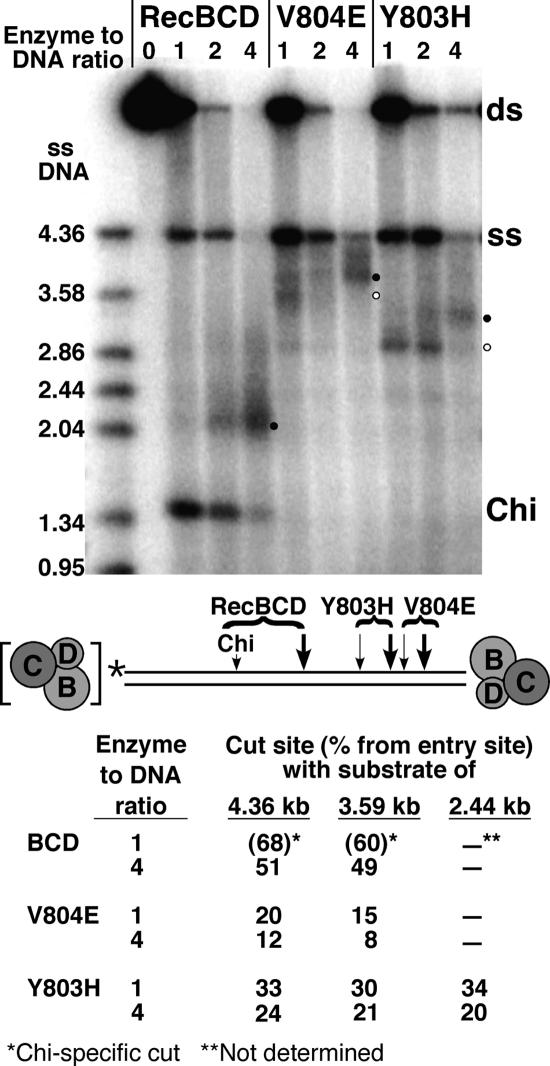

Figure 4.

The position of the novel length-dependent cut changes when two mutant RecBCD enzymes collide. Products of reactions with the DNA substrate (0.5 nM) diagrammed below the gel were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. At high mutant RecBCD concentration (four RecBCD molecules per DNA molecule), the novel cuts (bullets on gel and thick arrows on diagram) are closer to the RecBCD entry site than at low RecBCD concentration (one RecBCD molecule per DNA molecule; open circles on gel and thin arrows on diagram). Note that wild-type RecBCD cuts at Chi at low concentration but in the middle of the substrate at high concentration. Markers in the left-most lane are boiled (ss) samples of the [5′-32P] DNA substrate and subfragments of it. These reactions did not contain SSB. Data at the bottom are the lengths of the cut products as a fraction of the length of three different [5′-32P]-labeled substrates at low and high enzyme concentration; only data for the 4.36-kb substrate are shown here. In each case, cutting occurs closer to the entry site at high enzyme concentration.

As shown above (Fig. 2A), the mutant enzymes did not cut at Chi, but as predicted by our hypothesis, they cut closer to the entry point at high enzyme concentration than at low concentration (Fig. 4). On three different length substrates, the distance from the entry site to the cut site was about one-half of the distance at low enzyme concentration. Collision at the midpoint of the DNA is thus equivalent to using a half-length DNA substrate. These results show that the position of the novel cut is altered when the distance that the enzyme travels is altered. Since RecD is the faster helicase (Table 2; Taylor and Smith 2003), we infer that termination of RecD’s travel induces RecD to signal cutting by the RecB subunit. (It is not clear why wild-type RecBCD at high concentration cuts in the middle of the substrate rather than at one-half of its characteristic x/y ratio of RecB:RecD helicase rates. Failure to cut there may be related to its failure to cut at low concentration at any point in the absence of Chi [Fig. 2A].)

Slowing RecD helicase abolishes cutting at novel positions and can revive Chi cutting

To test more directly the hypothesis that the mutant enzymes cut DNA when RecD translocation terminates at the end of its substrate strand, we coupled the recD2177 (K177Q) mutation with the new recB2732 (Y803H) or recB2734 (V804E) mutation to make doubly mutant RecBCD enzymes. The recD2177 (K177Q) mutation, in the ATPase site, slows RecD to 32 nucleotides (nt) per second, ∼5% of the wild-type rate (Taylor and Smith 2003). For the Y803H and Y804E singly mutant enzymes, the rates of RecB-mediated unwinding are 122 and 97 base pairs (bp) per second, respectively (Table 2). Consequently, in the doubly mutant enzymes, RecB is expected to move more rapidly than RecD; RecB would reach the end of the substrate before RecD, and the signal to cut the DNA might not be generated. As predicted, the novel length-dependent cuts made by the single recB mutant enzymes were not detectably made by the doubly mutant enzymes (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S4). Less than 2% of the DNA was cut by the doubly mutant enzymes, whereas ∼35% of the DNA was cut by the singly mutant enzymes. These results indicate that the RecD subunit is involved in generating the novel length- dependent cuts on DNA.

Remarkably, altering the RecD subunit, in the RecBY803HCDK177Q enzyme, restored Chi-dependent cuts (Fig. 2A). This is consistent with cells bearing this doubly mutant enzyme showing Chi hot spot activity (Table 1) and with RecBY803H and likely RecC encountering Chi before the very slow RecDK177Q subunit gets to the end of the DNA (Table 2). The RecBV804ECDK177Q enzyme did not cut at Chi (Supplementary Fig. S4), consistent with the lack of Chi hot spot activity in cells with this doubly mutant enzyme (Table 1).

Mutant enzymes do not load RecA onto the novel cut products

After encountering Chi, wild-type RecBCD loads RecA protein onto the newly generated 3′ end (Anderson and Kowalczykowski 1997b). To determine if this Chi-dependent alteration occurs in the mutant enzymes after they generate their length-dependent cuts, we tested RecA loading onto DNA substrates with or without Chi. Each mutant RecBCD enzyme made the expected novel cut fragments, but in neither case was there detectable loading of RecA onto this product (Supplementary Fig. S5). RecA loading was measured by resistance of the cut product to digestion by exonuclease I, which is specific for 3′ ssDNA ends and is inhibited by RecA protein on the DNA. The failure to load RecA can account for the Rec− phenotype of these mutants (Table 1), the basis of their isolation.

Discussion

We describe here novel mutant RecBCD enzymes whose behavior, both in cells and when purified, suggests that the RecD subunit signals the RecB subunit to cut DNA. These results lead to a new hypothesis of how Chi sites regulate wild-type RecBCD enzyme, the complex protein machine that initiates the major pathway for DSB repair and homologous recombination in E. coli. Below, we discuss this hypothesis, support for it, and tests of the hypothesis.

Amino acid substitutions in helicase motif VI slow RecB and confer a novel DNA cutting activity dependent on the substrate length

The two mutants described here change two highly conserved amino acids in helicase motif VI, whose consensus sequence in 39 bacterial RecB proteins is RLLYVA-TR, where “-” is a not-well-conserved amino acid. In E. coli’s RecB, this sequence is RLLYVALTR; the mutants described here are altered in the amino acids underlined. In RecBCD this sequence is part of a 24-amino-acid-long α-helix that does not appear to contact DNA during unwinding but lies close and parallel to another short helix that likely does (Singleton et al. 2004). Studies of mutants with alterations in motif VI in several superfamily I helicases suggest that amino acids in this motif are required to couple ATP hydrolysis to DNA movement (e.g., Graves-Woodward et al. 1997). In one case, E. coli UvrD (helicase II), the T → A amino acid alteration in this motif changes the conformation of the protein, as indicated by increased sensitivity to limited proteolysis (Hall et al. 1998). Thus, this long α-helix may be important in transducing information, via a conformational change, between the ATPase and helicase active sites. This interpretation is consistent with the increased apparent KM for ATP and the decreased RecB helicase rates in the RecBCD mutants studied here (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S1). We suggest that in wild-type RecBCD, this helix is important also for the transduction of the Chi-dependent signal that alters the activities of the enzyme after acting at Chi (Taylor and Smith 1992).

The mutations studied here impart a novel phenotype to RecBCD—the ability to determine a fraction of the length of the DNA substrate and to cut the DNA at that point. The simplest interpretation is that this “calculation” reflects the ratio of the rates of movement of the RecB and RecD helicases (Fig. 1A, x/y; Table 2). In the mutants, the RecD helicase moved at the same rate as it does in wild-type RecBCD, but the RecB helicase was slower than that in wild type, 31% of the wild-type rate for V804E and 39% for Y803H. The near equality of the RecB:RecD ratio and the position of the cut for each enzyme (Table 2) supports this simple interpretation. Furthermore, since RecB has the nuclease domain (Yu et al. 1998b) and the position of the cut is indistinguishable from the point at which RecB’s nuclease domain would be when RecD reaches the end of the DNA, we conclude that cutting, by RecB, is induced when RecD reaches the end of the DNA and stops unwinding DNA.

We tested the interpretation that the mutant enzymes cut DNA when RecD stops unwinding in two ways. (1) Introduction of the recD2177 (K177Q) mutation in the RecD ATP site (Korangy and Julin 1992) slows the RecD helicase to ∼5% of the wild-type RecD rate (Taylor and Smith 2003). This rate is slower than that of the RecBY803H or RecBV804E mutant subunit (Table 2). Thus, in the doubly mutant enzymes RecB is expected to reach the DNA end before RecD does. As predicted, these doubly mutant enzymes did not cut at the novel length-dependent position (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S4). (2) When two wild-type RecBCD molecules simultaneously unwind a DNA molecule, one from each end of the DNA, the enzymes cut when they collide near the middle of the DNA (Dixon and Kowalczykowski 1993). When the new mutant enzymes were similarly tested, cutting occurred at approximately one-half the distance from the entry end to the position of the novel cut observed at low enzyme concentration, when only one enzyme molecule is present on the DNA (Fig. 4). Thus, whether RecD stops at the end of the DNA or upon collision with another RecBCD molecule, cutting is induced at the position where RecB is expected to be located.

Wild-type RecBCD generates a 3′ DNA end a few nucleotides 3′ of the Chi sequence. With excess ATP, this occurs by a simple nick (Taylor et al. 1985), whereas with excess Mg2+, degradation of the 3′-ended strand ceases at or near Chi (Dixon and Kowalczykowski 1993; Taylor and Smith 1995b). The mutants studied here appear to generate 3′ ends in a similar manner under these two reaction conditions (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S6; S.K. Amundsen and A.F. Taylor, unpubl.) but at novel length-dependent positions. We suppose that the basic mechanism that induces the cut is the same as that in wild-type RecBCD but that the signal for this induction is different, as discussed below. Although new 3′ ssDNA ends were produced by both the mutant and wild-type enzymes, the mutants were recombination deficient (Table 1). This deficiency is likely due to the mutants’ inability to load RecA protein onto the newly generated 3′ end (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, the mutants mimic only part of the change at Chi—they cut DNA but do not load RecA.

Our results indicate that in the mutant enzymes, RecD signals RecB to cut the DNA. Below, we extend this explanation into a new hypothesis for how, in wild-type enzyme, Chi signals RecB to cut the DNA and to load RecA protein to initiate strand exchange.

A ‘signal transduction cascade’ hypothesis for Chi’s regulation of wild-type RecBCD enzyme

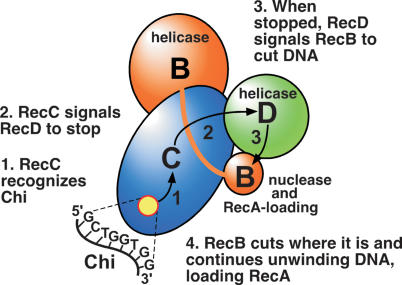

Based on these and other observations, especially the RecBCD crystal structure and its interpretation (Singleton et al. 2004), we propose the following hypothesis for Chi’s regulation of wild-type RecBCD enzyme (Fig. 5). The 3′-ended strand of DNA passes through the RecB helicase and into a tunnel in RecC (Fig. 1C). Critical amino acids in RecC engage Chi (5′-GCTGGTGG-3′) on that strand, which is necessary and sufficient for maximal Chi activity (Smith et al. 1981; Bianco and Kowalczykowski 1997), and RecC signals the RecD helicase to stop unwinding DNA. When RecD stops, it signals RecB to cut the DNA four to six nucleotides to the 3′ side of Chi (Taylor et al. 1985) and to begin loading RecA onto the newly generated 3′-ended ssDNA (Anderson and Kowalczykowski 1997b). Unwinding continues, with RecB now the leading helicase and loading RecA at intermittent points. RecA’s cooperative binding fills the gaps to form a continuous RecA-ssDNA filament, which undergoes strand exchange with a homologous duplex (Fig. 1B). At an as-yet-undetermined point, RecBCD dissociates from the DNA, and the three subunits disassemble, leaving RecBCD inactive (Taylor and Smith 1999).

Figure 5.

Model for regulation of RecBCD enzyme by Chi sites: an intersubunit signal transduction cascade. At step 1, RecC (blue ellipsoid) recognizes Chi when the DNA strand with the 3′ end passes from the RecB helicase domain (large orange sphere) through a tunnel in RecC toward the RecB nuclease domain (small orange sphere) (see Fig. 1). At step 2, RecC signals the RecD helicase (green sphere) to stop unwinding. At step 3, RecD signals the RecB nuclease domain to cut the DNA near Chi. At step 4, RecB loads RecA onto the newly generated 3′ end and continues to unwind DNA. RecD’s signal may pass directly to the RecB nuclease–RecA loading domain, as shown, or through the RecB helicase domain, which contains the amino acids altered in the mutants studied here.

Genetic and biochemical studies support this hypothesis. In the absence of ATP, RecBCD binds tightly to a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) end (KD ≈ 0.1 nM) and unwinds a few base pairs, with the 3′ end contacting RecB and the 5′ end contacting RecC and RecD (Fig. 1; Ganesan and Smith 1993; Taylor and Smith 1995a; Farah and Smith 1997). An open tunnel in RecB and RecC is plausibly the path of the 3′-ended strand toward the nuclease domain in RecB (Singleton et al. 2004). Alteration of five to eight amino acids in RecC in a class of compensating frameshift mutations, called recC* (Schultz et al. 1983; Arnold et al. 2000) or of a single amino acid in the recC343 (TexA) mutant (Lundblad et al. 1984; S.K. Amundsen, unpubl.) greatly reduces Chi activity. These amino acids line part of the tunnel in RecC. The distance from these amino acids to the nuclease active site would readily accommodate four to six nucleotides (Singleton et al. 2004), the distance between Chi and the cuts that depend on it (Taylor et al. 1985).

Consistent with our hypothesis, RecD plays a central role in the regulation of RecBCD. Although the nuclease active site is in RecB (Yu et al. 1998b; Zhang and Julin 1999), recD-null mutants are nuclease deficient (Amundsen et al. 1986). RecD must therefore regulate RecB’s nuclease activity. In addition, RecBC, but not RecBCD, loads RecA protein in the absence of Chi (Churchill et al. 1999); RecD must therefore inhibit the loading of RecA, which may be directed by part of RecB (Spies and Kowalczykowski 2006). recB mutants altered in the nuclease active site are Rec− and do not load RecA unless the RecD subunit is removed (Anderson et al. 1999; Amundsen et al. 2000). It is therefore plausible that the Chi signal, which alters the nuclease and RecA loading activities, is transmitted via RecD. In the crystal structure, the ordered part of RecD does not contact RecB (Fig. 1C; Singleton et al. 2004) but does come within ∼0.8 nm of the RecB nuclease domain, which may overlap the RecA loading domain (Spies and Kowalczykowski 2006). We propose that Chi alters the conformation of RecC, which does contact RecD, and moves RecD against the RecB nuclease domain, thereby altering its activity. Alternatively, RecD may contact RecB during unwinding and, after receiving the Chi signal from RecC, alter the RecB helicase domain, which in turn affects the RecB nuclease domain via the ∼30-amino-acid-long tether connecting these domains (Fig. 1C); this possibility is consistent with our interpretation of the recB helicase domain mutants described in this study.

Studies of single RecBCD molecules by fluorescence microscopy also support this hypothesis. Unwinding of the DNA duplex pauses at or near Chi, and the length of the pause is proportional to the distance of the Chi site from the DNA end at which RecBCD initiated unwinding (Spies et al. 2003). We interpret these results to mean that RecD, the leading helicase before Chi (Taylor and Smith 2003), stops unwinding at or near Chi, in accord with our hypothesis (Fig. 5). RecB continues, perhaps without any pause, to travel along the ss loop for a time proportional to the loop length (i.e., also proportional to the distance of Chi from the DNA end) (Fig. 1A). After traversing the loop, RecB becomes the leading (unwinding) helicase after Chi but at a rate slower than RecD was before Chi, as observed (Spies et al. 2003). We suppose that the slowing or elimination of the RecD helicase reflects a conformational change as part of the Chi signal transduction.

Our hypothesis is distinct from previous hypotheses of how Chi affects RecBCD enzyme. According to one hypothesis (Thaler et al. 1988), RecD is ejected at Chi. Early enzymatic studies argued against this possibility, however: After acting at Chi, the enzyme retains nuclease activity (Taylor and Smith 1992), whereas RecBC (i.e., without RecD) lacks nuclease activity (Amundsen et al. 1986). Furthermore, subsequent light microscopy studies of single RecBCD molecules showed that RecD remains with the enzyme after Chi (Dohoney and Gelles 2001; Handa et al. 2005). According to another hypothesis (Yu et al. 1998a), the RecB nuclease domain “swings” from one side of the enzyme, where it digests the 3′ → 5′ strand, to the other side, where it digests the 5′ → 3′ strand. Singelton et al. (2004) modified this view and hypothesized that at Chi the 3′ → 5′ strand, the one with Chi, moves from a channel in RecC aimed toward the nuclease site into another channel aimed away from the nuclease site. This change might be effected by a RecB α-helix swinging to block the first channel. This hypothesis is consistent with ours, which in addition specifies how Chi effects this and other changes in the enzyme.

Although aspects of our hypothesis (Fig. 5) are speculative and require further support, it is consistent with current observations, as noted above, and makes testable predictions. Specific mutations in each gene should disrupt the signal transduction cascade. In addition to the recC* mutations that appear to abolish the Chi–RecC interaction (see above), there should be mutant forms of RecC that cannot transmit the signal to RecD, mutant forms of RecD that cannot receive the signal from RecC or that cannot transmit the signal to RecB, and mutant forms of RecB that cannot receive the signal from RecD. Previously described recC and recB mutations may correspond to these classes: recC2145, recB2154, and recB2155 are Rec− Nuc+ Chi−, like the mutants described here, and may be unable to transmit or receive the Chi signal (Amundsen et al. 1990). Our model predicts a class of recD mutations that cannot receive or transmit the signal and would be Rec−. Such mutations have not been reported to date, but recD-null mutations are Rec+ Nuc− Chi−, as predicted if Chi annuls the regulatory roles of RecD (Amundsen et al. 2000). We suppose that the transduction of the Chi signal involves conformational changes in each of the RecBCD subunits; such changes might be detectable by limited proteolysis or spectroscopy of fluorescently labeled subunits.

Intersubunit signaling in other complex protein machines

The conceptual model of intersubunit signaling, such as that proposed here for RecBCD, may be applicable to a broad range of complex protein machines. Particularly relevant here are two examples of enzymes with three types of subunits and multiple activities on DNA, like RecBCD. (1) Mismatch correction in E. coli depends on the MutS, MutH, and MutL proteins. MutS binds to mismatched bases in DNA, the MutH latent endonuclease binds to a distant hemimethylated DNA site, and MutL appears to connect MutS and MutH (Iyer et al. 2006). The MutH nuclease is activated by MutS and MutL in the presence of ATP and a mismatch. The mechanism of the activation is unclear but likely involves transduction of a signal from MutS to MutH, perhaps via MutL. (2) Type I restriction enzymes bind to a specific DNA sequence, travel along the DNA, and cut at a distant site when travel stops, due to collision between two enzymes or a structural constraint in the DNA (Murray 2000). In these enzymes, the HsdS subunit binds a specific DNA sequence but is aided by the HsdM subunit, which contains the methyltransferase domain; the HsdR subunit contains the endonuclease domain. If the DNA sequence is hemimethylated, the HsdM subunit acts before travel is initiated, but if the sequence is unmethylated, travel commences and the HsdR subunit acts. Signaling between the subunits therefore must regulate modification versus restriction. Another related example is the type II DNA topoisomerases, in which there appears to be signaling between the ATPase site in one subunit and the DNA breaking–rejoining “gate” in another subunit (Bates and Maxwell 2007). Mutational alterations of these proteins may help elucidate the putative intersubunit signal transduction, as reported here for RecBCD enzyme.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, phage, and plasmids

Bacterial strains are listed in Supplementary Table S1 with their genotypes and sources. Plasmids are listed in Supplementary Table S2. For visual clarity, allele numbers and polypeptide designations are expressed as superscripts when more than one recBCD gene or RecBCD polypeptide are designated. Bacterial strains were constructed by phage P1 transduction, CaCl2-mediated transformation, electroporation, or “recombineering” (Ausubel et al. 2003; Thomason et al. 2005). Plasmids were constructed by standard procedures (Ausubel et al. 2003).

Culture media and genetic assays

Culture media have been described (Cheng and Smith 1989). Chi hot spot activity and recombination proficiency were measured in λ vegetative crosses (Stahl and Stahl 1977), and E. coli recombination proficiency in Hfr crosses (Schultz et al. 1983).

Mutant isolation

Mutations in the C-terminal part of recB were generated by mutagenic PCR (Ausubel et al. 2003). Two primer pairs were used—one amplifying codons 712–1181, and the other pair codons 794–1181 (Supplementary Table S3); recB has 1181 codons including that for termination. Each PCR contained, in 100 μL, 20 fmol of plasmid pDWS2 DNA, 30 pmol of each primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MnCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 1 mM dCTP and dTTP, 0.2 mM dATP and dGTP, and 5 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) and ran for 30 cycles (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C). The PCR products were digested with BglII, which cleaves between recB codons 797 and 798, and with BseRI, which cleaves four nucleotides after the recB termination codon. The largest fragment (1.1 kb) was “swapped” with the corresponding recB+ fragment of pMR3. Approximately 5000 ampicillin-resistant (AmpR) transformants of strain V2959 [ΔrecBCD2731∷kan Δ(lacIZYA–argF)U169] were screened for recombination deficiency (Rec−) by toothpick transfer of colonies to minimal lactose agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and kanamycin (25 μg/mL) and spread with ∼108 stationary-phase cells of strain KL226 (lac+ Hfr PO 12.2). Approximately 1000 Rec− colonies (those unable to generate Lac+ AmpR KanR recombinant colonies) were tested by cross-streaking colonies from an LB-ampicillin master plate onto LB agar with phage P2 (applied as lines of ∼20 μL of 108 phage per milliliter); growth of P2 appears to require RecBCD exonuclease (Nuc+) (Amundsen et al. 1990). (Many of the Rec− Nuc− isolates had plasmids without the BglII–BseRI fragment, reflecting inefficient swapping.) Lawns of ∼200 Rec− Nuc+ candidates were tested by spot tests for growth of λ Δ(red–gam) χ+ and χo phages, which do not make plaques on Rec− Nuc+ strains, and of phage P1, which does not make plaques on Rec− strains (Schultz et al. 1983; Amundsen et al. 1990, 2000). Plasmids from ∼50 stable Rec− Nuc+ candidates were isolated and introduced into strain V2831 (ΔrecBCD2731∷kan); these transformants were tested quantitatively as in Table 1. The recB nucleotide sequence was determined for 11 of the most Rec− candidates. The recB2732 (Y803H) and recB2734 (V804E) mutations were introduced into plasmid pSA124 using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and mutant oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S3). These mutations were transferred to plasmid pMR3 by fragment swapping as described above. Double recB recD mutants were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis of pMR3 to introduce the recD2177 mutation, followed by swapping of the BseRI–BglII fragment from pSA176 or pSA178 to introduce the recB2732 or recB2734 mutation.

Enzyme purification and assays

The purification of wild-type RecBCD enzyme has been described (Taylor and Smith 2003). Mutant RecBCD enzymes were purified from strain V2831 (ΔrecBCD2731) containing derivatives of pMR3 by similar methods. In brief, cells from a 12 L of culture in Terrific Broth (Fisher) were lysed, and enzymes were purified by column chromatography—HiTrap Q Sepharose, HiPrep Sephacryl S-300 HR, and HiTrap Heparin (all from GE Lifesciences), followed by CHTII hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) for the single mutants or ssDNA agarose (GE Lifesciences) for the double mutants. The final product (∼1 mg) was judged to be ∼80% pure by staining with SimplyBlue (Invitrogen) an SDS–polyacrylamide gel loaded with 0.5 μg of protein.

Assays for RecBCD ds and ss exonuclease used native and boiled [3H] T7 DNA, respectively (Eichler and Lehman 1977). Gel-electrophoretic assays for DNA unwinding, Chi cutting, and RecA loading were as described (Taylor et al. 1985; Amundsen et al. 2000; Taylor and Smith 2003) with 5 mM ATP, 3 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 1 μM SSB (Promega), except as noted in Figure 4 and Supplementary Figures S3 and S5. Agarose gels (0.7%; 22 cm long) in TBE buffer (Ausubel et al. 2003) were run at room temperature for 2.5 h at 100 V (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Figs. S4, S5) or for ∼16 h at ∼50 V (Figs. 2B, 4; Supplementary Figs. S2, S3). Analysis of Typhoon Trio PhosphorImage files (GE Lifesciences) used ImageQuant TL software (Amersham); size markers were fit to a log-linear straight line (r2 > 0.997). EM assays for DNA unwinding (Taylor and Smith 2003) contained 5 mM ATP, 1 mM Mg2+, and 1 μM SSB; rates were calculated from molecules whose complementary unwound strands differed in length by <33%.

For the experiments in Figures 2A and 4 and Supplementary Figures S4 and S5, DNA substrates were prepared from pBR322 χ+F or χo (4361 bp) by cutting with HindIII, treating with phosphatase, labeling the 5′ ends using polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P] ATP (Amundsen et al. 2000), and cutting with ClaI, which produces a 4355-bp fragment with one of the two 32P labels and two short fragments (five and seven nucleotides) not seen in our analyses. For the experiments in Figure 2B and Supplementary Figures S2 and S3, the DNA substrates were similarly prepared from pBR322 χo DNA by cutting with StyI, labeling the 5′ ends, cutting with BsmI, and separating the 4351-bp fragment from a short fragment using an S200 spin column. Subfragments for RecBCD reactions and for size markers were produced by subsequent digestion of the 4351-bp fragment with NruI, SalI, HindIII, PvuI, AlwNI, AflIII, NdeI, or Tth111I.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harvey Eisen, Martin Gellert, Paul Modrich, and Noreen Murray for helpful discussions of nucleic acid enzymes, and Gareth Cromie and Luther Davis for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by research grant GM031693 from the National Institutes of Health to G.R.S., and institutional support from the Division of Basic Sciences of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1605807

References

- Alberts B. The cell as a collection of protein machines: Preparing the next generation of molecular biologists. Cell. 1998;92:291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen S.K., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Chi hotspot activity in Escherichia coli without RecBCD exonuclease activity: Implications for the mechanism of recombination. Genetics. 2007;176:41–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen S.K., Taylor A.F., Chaudhury A.M., Smith G.R., Taylor A.F., Chaudhury A.M., Smith G.R., Chaudhury A.M., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. recD: The gene for an essential third subunit of exonuclease V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1986;83:5558–5562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen S.K., Neiman A.M., Thibodeaux S.M., Smith G.R., Neiman A.M., Thibodeaux S.M., Smith G.R., Thibodeaux S.M., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Genetic dissection of the biochemical activities of RecBCD enzyme. Genetics. 1990;126:25–40. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen S.K., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. The RecD subunit of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme inhibits RecA loading, homologous recombination and DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:7399–7404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen S.K., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. A domain of RecC required for assembly of the regulatory RecD subunit into the Escherichia coli RecBCD holoenzyme. Genetics. 2002;161:483–492. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.G., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The recombination hot spot χ is a regulatory element that switches the polarity of DNA degradation by the RecBCD enzyme. Genes & Dev. 1997a;11:571–581. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.G., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The translocating RecBCD enzyme stimulates recombination by directing RecA protein onto ssDNA in a χ regulated manner. Cell. 1997b;90:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D.G., Churchill J.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Churchill J.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. A single mutation, RecBD1080A, eliminates RecA protein loading but not Chi recognition by RecBCD enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27139–27144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D.A., Handa N., Kobayashi I., Kowalczykowski S.C., Handa N., Kobayashi I., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kobayashi I., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. A novel, 11 nucleotide variant of χ, χ*: One of a class of sequences defining the Escherichia coli recombination hotspot χ. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:469–479. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F.M., Brent R., Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Brent R., Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Smith J.A., Struhl K., eds , Struhl K., eds , eds , editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bates A.D., Maxwell A., Maxwell A. Energy coupling in Type II topoisomerases: Why do they hydrolyze ATP? Biochemistry. 2007;46:7929–7941. doi: 10.1021/bi700789g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P.R., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The recombination hotspot χ is recognized by the translocating RecBCD enzyme as the single strand of DNA containing the sequence 5′-GCTGGTGG-3′. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:6706–6711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K.C., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Distribution of Chi-stimulated recombinational exchanges and heteroduplex endpoints in phage λ. Genetics. 1989;123:5–17. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill J.J., Anderson D.G., Kowalczykowski S.C., Anderson D.G., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The RecBC enzyme loads RecA protein onto ssDNA asymmetrically and independently of χ resulting in constitutive recombination activation. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:901–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D.A., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. Homologous pairing in vitro stimulated by the recombination hotspot, Chi. Cell. 1991;66:361–371. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90625-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D.A., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The recombination hotspot χ is a regulatory sequence that acts by attenuating the nuclease activity of the E. coli RecBCD enzyme. Cell. 1993;73:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90162-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohoney K.M., Gelles J., Gelles J. χ-sequence recognition and DNA translocation by single RecBCD helicase/nuclease molecules. Nature. 2001;409:370–374. doi: 10.1038/35053124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler D.C., Lehman I.R., Lehman I.R. On the role of ATP in phosphodiester bond hydrolysis catalyzed by the RecBC deoxyribonuclease of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah J.A., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. The RecBCD enzyme initiation complex for DNA unwinding: Enzyme positioning and DNA opening. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:699–715. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Strand-specific binding to duplex DNA ends by the subunits of Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;229:67–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves-Woodward K.L., Gottlieb J., Challberg M.D., Weller S.K., Gottlieb J., Challberg M.D., Weller S.K., Challberg M.D., Weller S.K., Weller S.K. Biochemical analyses of mutations in the HSV-1 helicase–primase that alter ATP hydrolysis, DNA unwinding, and coupling between hydrolysis and unwinding. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4623–4630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M.C., Ozsoy A.Z., Matson S.W., Ozsoy A.Z., Matson S.W., Matson S.W. Site-directed mutations in motif VI of Escherichia coli DNA helicase II result in multiple biochemical defects: Evidence for the involvement of motif VI in the coupling of ATPase and DNA binding activities via conformational changes. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:257–271. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa N., Bianco P.R., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Bianco P.R., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. Direct visualization of RecBCD movement reveals cotranslocation of the RecD motor after Chi recognition. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:745–750. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer R.R., Pluciennik A., Burdett V., Modrich P.L., Pluciennik A., Burdett V., Modrich P.L., Burdett V., Modrich P.L., Modrich P.L. DNA mismatch repair: Functions and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:302–323. doi: 10.1021/cr0404794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korangy F., Julin D.A., Julin D.A. Alteration by site-directed mutagenesis of the conserved lysine residue in the ATP-binding consensus sequence of the RecD subunit of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:1727–1732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad V., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Kleckner N., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Kleckner N., Smith G.R., Kleckner N., Kleckner N. Unusual alleles of recB and recC stimulate excision of inverted repeat transposons Tn10 and Tn5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984;81:824–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray N.E. Type I restriction systems: Sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:412–434. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.412-434.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D.B., Goldberg E.B., Goldberg E.B. Protection of parental T4 DNA from a restriction exonuclease by the product of gene 2. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;116:877–881. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D.W., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Escherichia coli RecBC pseudorevertants lacking Chi recombinational hotspot activity. J. Bacteriol. 1983;155:664–680. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.664-680.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton M.R., Dillingham M.S., Gaudier M., Kowalczykowski S.C., Wigley D.B., Dillingham M.S., Gaudier M., Kowalczykowski S.C., Wigley D.B., Gaudier M., Kowalczykowski S.C., Wigley D.B., Kowalczykowski S.C., Wigley D.B., Wigley D.B. Crystal structure of RecBCD enzyme reveals a machine for processing DNA breaks. Nature. 2004;432:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.R. RecBCD enzyme. In: Eckstein F., Lilley D.M.J., Lilley D.M.J., editors. Nucleic acids and molecular biology. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1990. pp. 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.R. Conjugational recombination in E. coli: Myths and mechanisms. Cell. 1991;64:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90205-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.R. Homologous recombination near and far from DNA breaks: Alternative roles and contrasting views. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2001;35:243–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.R., Kunes S.M., Schultz D.W., Taylor A., Triman K.L., Kunes S.M., Schultz D.W., Taylor A., Triman K.L., Schultz D.W., Taylor A., Triman K.L., Taylor A., Triman K.L., Triman K.L. Structure of Chi hotspots of generalized recombination. Cell. 1981;24:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies M., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. The RecA binding locus of RecBCD is a general domain for recruitment of DNA strand exchange proteins. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies M., Bianco P.R., Dillingham M.S., Handa N., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Bianco P.R., Dillingham M.S., Handa N., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Dillingham M.S., Handa N., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Handa N., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Baskin R.J., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. A molecular throttle: The recombination hotspot Chi controls DNA translocation by the RecBCD helicase. Cell. 2003;114:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies M., Dillingham M.S., Kowalczykowski S.C., Dillingham M.S., Kowalczykowski S.C., Kowalczykowski S.C. Translocation by the RecB motor is an absolute requirement for χ-recognition and RecA protein loading by RecBCD enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37078–37087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl F.W., Stahl M.M., Stahl M.M. Recombination pathway specificity of Chi. Genetics. 1977;86:715–725. doi: 10.1093/genetics/86.4.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Unwinding and rewinding of DNA by the RecBC enzyme. Cell. 1980;22:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. RecBCD enzyme is altered upon cutting DNA at a Chi recombination hotspot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:5226–5230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Monomeric RecBCD enzyme binds and unwinds DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1995a;270:24451–24458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Strand specificity of nicking of DNA at Chi sites by RecBCD enzyme: Modulation by ATP and magnesium levels. J. Biol. Chem. 1995b;270:24459– 24467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. Regulation of homologous recombination: Chi inactivates RecBCD enzyme by disassembly of the three subunits. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:890–900. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. RecBCD enzyme is a DNA helicase with fast and slow motors of opposite polarity. Nature. 2003;423:889–893. doi: 10.1038/nature01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.F., Schultz D.W., Ponticelli A.S., Smith G.R., Schultz D.W., Ponticelli A.S., Smith G.R., Ponticelli A.S., Smith G.R., Smith G.R. RecBC enzyme nicking at Chi sites during DNA unwinding: Location and orientation dependence of the cutting. Cell. 1985;41:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler D.S., Sampson E., Siddiqi I., Rosenberg S.M., Stahl F.W., Stahl M., Sampson E., Siddiqi I., Rosenberg S.M., Stahl F.W., Stahl M., Siddiqi I., Rosenberg S.M., Stahl F.W., Stahl M., Rosenberg S.M., Stahl F.W., Stahl M., Stahl F.W., Stahl M., Stahl M. A hypothesis: Chi-activation of RecBCD enzyme involves removal of the RecD subunit. In: Friedberg E., Hanawalt P., Hanawalt P., editors. Mechanisms and Consequences of DNA Damage Processing. Alan R. Liss; New York: 1988. pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason L., Court D.L., Bubunenko M., Costantino N., Wilson H., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Court D.L., Bubunenko M., Costantino N., Wilson H., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Bubunenko M., Costantino N., Wilson H., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Costantino N., Wilson H., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Wilson H., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Datta S., Oppenheim A., Oppenheim A. Recombineering: Genetic engineering in bacteria using homologous recombination. In: Ausubel F.M., et al., editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley; New York: 2005. unit 1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Souaya J., Julin D.A., Souaya J., Julin D.A., Julin D.A. The 30-kDa C-terminal domain of the RecB protein is critical for the nuclease activity, but not the helicase activity, of the RecBCD enzyme from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998a;95:981–986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Souaya J., Julin D.A., Souaya J., Julin D.A., Julin D.A. Identification of the nuclease active site in the multifunctional RecBCD enzyme by creation of a chimeric enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1998b;283:797–808. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.J., Julin D.A., Julin D.A. Isolation and characterization of the C-terminal nuclease domain from the RecB protein of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4200–4207. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.21.4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]