Abstract

Little is known regarding the basis for selection of the semi-invariant αβ T cell receptor (TCR) expressed by natural killer T (NKT) cells or how this mediates recognition of CD1d–glycolipid complexes. We have determined the structures of two human NKT TCRs that differ in their CDR3β composition and length. Both TCRs contain a conserved, positively charged pocket at the ligand interface that is lined by residues from the invariant TCR α- and semi-invariant β-chains. The cavity is centrally located and ideally suited to interact with the exposed glycosyl head group of glycolipid antigens. Sequences common to mouse and human invariant NKT TCRs reveal a contiguous conserved “hot spot” that provides a basis for the reactivity of NKT cells across species. Structural and functional data suggest that the CDR3β loop provides a plasticity mechanism that accommodates recognition of a variety of glycolipid antigens presented by CD1d. We propose a model of NKT TCR–CD1d–glycolipid interaction in which the invariant CDR3α loop is predicted to play a major role in determining the inherent bias toward CD1d. The findings define a structural basis for the selection of the semi-invariant αβ TCR and the unique antigen specificity of NKT cells.

The CD1 molecules are a cluster of nonpolymorphic, MHC class I–like glycoproteins that present lipid-based antigens to αβ T cells (1, 2). They comprise group I, CD1a, CD1b, CD1c, and CD1e molecules found in humans and the group II CD1d molecule that is expressed in humans, mice, and rats (1, 2). CD1d binds both self and foreign glycolipids (3–11), including the glycosphingolipid α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) (3), an archetypal CD1d ligand that binds well to both human (hCD1d) and mouse CD1d (mCD1d) molecules and is a potent agonist for NKT cells (6, 12, 13). Recently, the structure of α-GalCer complexed with hCD1d and mCD1d was determined (14, 15), revealing that the acyl and sphingosine lipid chains of α-GalCer are buried in the antigen (Ag)-binding cavity, whereas the polar glycosyl head group protrudes from the CD1d cleft, where it is available for TCR interaction.

In contrast with polyclonal T cell recognition of the group I CD1 molecules (16), T cell recognition of CD1d–glycolipid complexes preferentially selects a semi-invariant TCR with a fixed α-chain and restricted β-chain, exclusively expressed by a subset of T cells known as NKT cells (17–19). The human invariant NKT cell TCR α-chain uses a Vα24-Jα18 (TRAV10-TRAJ18) (20) rearrangement that encodes a germline-encoded junctional sequence with a single codon deletion at the Vα−Jα junction, preserving amino acid sequence identity among human NKT TCR α-chains (12, 17–19). NKT cells are also present in other mammalian species, including mice that express a homologous invariant Vα14-Jα18 (TRAV11-J15) TCR α-chain rearrangement (20). Most human NKT cells express Vβ11 (TRBV25-1) (20) rearranged to form variable Dβ−Jβ combinations (17–19), whereas mouse NKT cells typically use either Vβ8.2, Vβ2, or Vβ7 (TRBV13-2, BV1, or BV29, respectively) (13, 20–22). The crucial role played by the NKT TCR α-chain is highlighted by the lack of NKT cells in TCR Jα18 gene-targeted mice (23). Alternatively, the role of Vβ in NKT cell selection and Ag recognition appears to be more subtle. For example, mouse NKT cells expressing Vβ8.2 display higher affinity binding toward IgG1-CD1d/αGalCer dimers than NKT cells expressing Vβ7 (24). These data have been interpreted to mean that complementarity-determining region (CDR)1β and CDR2β may be more important than CDR3β in NKT specificity (24), perhaps by mediating contacts with CD1d. This view is consistent with the high degree of natural variability in CDR3β sequences in NKT cells (25–27) and the comparable affinity of hybrid NKT TCRs substituted with noncognate mouse Vβ8.2 chains derived from conventional αβ T cells (28). However, the role of CDR3β in NKT cell specificity is controversial (25) in that some studies of mouse NKT hybridomas and CD1d mutants implicate CDR3β in the fine specificity of NKT Ag recognition (24, 29–31), including the suggestion of a novel CDR3β motif in human NKT cells expanded with α-GalCer (12). Remarkably, human NKT cells can also recognize mouse CD1d–α-GalCer complexes (32) and vice versa, indicating the evolutionary importance of NKT cells in immunity (33).

The structural explanation for selection of the semi-invariant NKT TCR, the role of the CDR3β loops in NKT specificity, and the basis for the reciprocal cross-species reactivity in Ag recognition by human and mouse NKT cells remain unresolved. Here, we describe the structure of two different semi-invariant TCRs, NKT12 and NKT15, from human NKT cells. The findings define a structural basis for the extreme αβ selection of NKT cell TCRs and indicate a mechanism for how the conformation and plasticity of the CDR3β loops could modulate binding of different CD1d-glycolipid antigens. A proposed model of the NKT TCR–α-GalCer complex provides new insights into Ag recognition and cross-species reactivity by NKT TCRs.

RESULTS

The semi-invariant T cell receptors

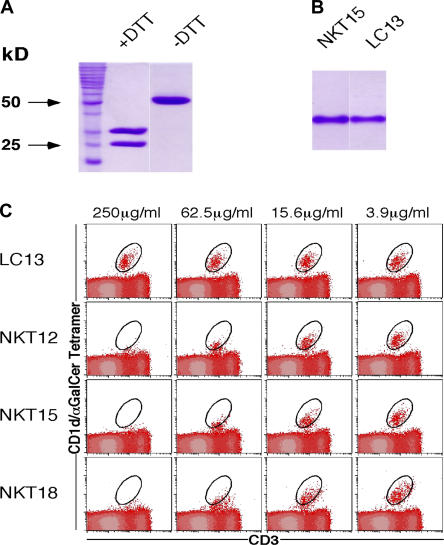

NKT cells were expanded from PBMCs by stimulation with α-GalCer, and cDNA corresponding to the TCRα and β gene transcripts was isolated. Three NKT receptors (NKT12, NKT15, and NKT18) were characterized as containing the invariant Vα24-Jα18 (TRAV10-TRAJ18) (20). NKT12 and NKT15 had Vβ11 (TRBV25-1) (20) rearranged to Dβ segment TRBD1 and Jβ segment TRBJ2-7 (20), whereas NKT18 Vβ11 was rearranged to Dβ TRBD1 and Jβ TRBJ2-1 (20). All three receptors differed in the length and composition of their CDR3β loops (Table I). Thus, the CDR3β of NKT15 is two residues longer than NKT12 and one residue longer than NKT18. The extracellular domains of the NKT12, NKT15, and NKT18 TCRs were expressed in Escherichia coli, then folded into a native conformation and purified by multiple rounds of chromatography as described in Materials and methods. The quality and function of the recovered protein was assessed by gel filtration size exclusion chromatography, ELISA reactivity with the conformation-dependent mAb 12H8 (anti-Cα/Cβ) (34) (not depicted), SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1 A), and native gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1 B). To further confirm that the complexes were in a natural conformation, they were tested for their ability to block binding of mouse CD1d/α-GalCer tetramers to mouse NKT cells. The assay confirmed that the soluble receptors retained their original antigen reactivity over a comparable dose range (Fig. 1 C). The NKT18 TCR was used for binding studies only, whereas the structures of the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs were determined. The NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs were crystallized in an orthorhombic space group and their structures were determined to 2.4Å and 2.2Å resolution, respectively. In addition, the NKT15 TCR also crystallized in a trigonal space group, and this crystal form was determined to 2.6 Å resolution. The collection statistics and refinement data are shown in Table II.

Table I.

Amino acid sequences of CDR3β residues in NKT TCRs

| TCR | Gene segment

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vβ | Dβ + N | Jβ | |

| NKT12 | 92CAS94 | 95TSRRG99 | 100SY105EQYFGPGTRLTVT117 |

| NKT15 | 92CASS95 | 96GLRDRGL102 | 103Y105EQYFGPGTRLTVT117 |

| NKT18 | 92CASS95 | 96APGTGD101 | 102N105EQFFGPGTRLTVL117 |

| LC13 | 92CASS95 | 96LGQA99 | 100Y105EQYFGPGTRLTVT117 |

Figure 1.

Structural and functional integrity of recombinant soluble NKT TCRs. (A) Purified bacterial NKT15 TCR was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing (+DTT, dithiothreitol) and nonreducing (−DTT) conditions demonstrating αβ heterodimers. (B) Native gel electrophoresis of folded αβ heterodimeric NKT15 and control LC13 TCRs. (C) Recombinant soluble NKT12, NKT15, NKT18, and control LC13 TCRs were tested for their ability to block binding of mouse CD1d/α-GalCer tetramers to murine thymocytes. Phycoerythrin-conjugated mCD1d/α-GalCer tetramers were preincubated with the indicated soluble TCRs over a range of TCR concentrations before staining mouse thymocytes. Cells were analyzed by two-color flow cytometry showing mCD1d/α-GalCer tetramer staining on the vertical axis and FITC-CD3 (mAb 145-2C11) staining on the horizontal axis. Cells staining positively with mCD1d/α-GalCer tetramer and FITC-CD3 are indicated with a circle.

Table II.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| NKT12 Orthorhombic |

NKT15 Orthorhombic |

NKT15 Trigonal |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Temperature | 100 K | 100 K | 100 K |

| Space group | C2221 | C2221 | P32 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) (a,b,c) | 58.92, 131.39, 117.80 | 59.84, 131.03, 116.85 | 66.67, 66.67, 182.41 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Total no. observations | 65,216 | 79,368 | 77,333 |

| No. unique observations | 18,076 | 22,974 | 27619 |

| Multiplicity | 3.60 | 3.45 | 2.80 |

| Data completeness (%) | 98.7 (96.8) | 97.5 (98.4) | 97.5 (98.4) |

| No. data >2σI (%) | 83.2 (58.5) | 82.5 (60.8) | 76.6 (42.2) |

| I/σI | 19.3 (3.8) | 15.8 (3.9) | 10.7 (2.3) |

| Rmerge/sym a (%) | 7.3 (41.2) | 8.9 (42.0) | 9.8 (54.0) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Nonhydrogen atoms | |||

| Protein | 3,528 | 3,542 | 7,084 |

| Water | 55 | 123 | 32 |

| Resolution (Å) | 65.65-2.4 | 65.51-2.2 | 60.86-2.6 |

| Rcryst b (%) | 23.0 | 21.0 | 20.7 |

| Rfree c (%) | 27.1 | 27.8 | 25.6 |

| RMS deviations from ideality | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.05 | 1.28 | 1.20 |

| Dihedrals (°) | 28.57 | 28.82 | 28.69 |

| Impropers (°) | 1.25 | 1.33 | 1.27 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| Most favored | 90.7 | 89.9 | 87.9 |

| And allowed region (%) | 9.1 | 9.3 | 10.8 |

| And disallowed region (%) | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Average main chain | 33.8 | 28.4 | 41.3 |

| Average side chain | 34.3 | 30.5 | 42.8 |

| Average water molecule | 28.2 | 30.8 | 43.5 |

| RMS deviation bonded Bs | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

.

.

for all data except as indicated in footnote “c.”

for all data except as indicated in footnote “c.”

7.3, 5.2, and 5% were used for the Rfree calculation for NKT12 (orthorhombic), NKT15 (orthorhombic), and NKT15 (trigonal), respectively.

RMS, root mean square.

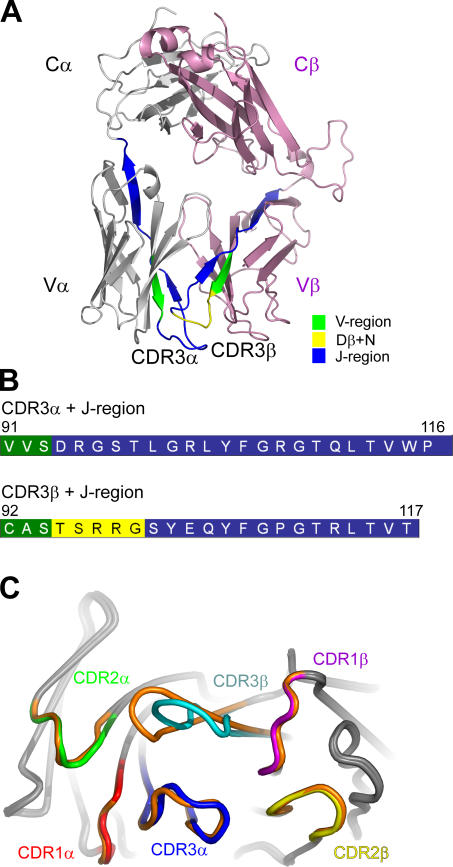

The overall structure of the NKT12 TCR comprises four immunoglobulin-like domains with a constant (C) and variable (V) domain per chain (Fig. 2 A). The V domain is composed of three CDRs; together, these six hypervariable loops form a potential ligand-binding site for the NKT12 TCR. Accordingly, the structure of the NKT12 TCR generally resembles that of other αβ TCRs. The interface between the α- and β-chains of the NKT12 TCR is extensive (buried surface area [BSA] of ≈4,100 Å2), with the V and C domains packing against each other. The BSA at the Vα-Vβ and Cα-Cβ interfaces, ≈1,400 Å2 and ≈2,700 Å2, respectively, falls within the range observed previously in other TCR structures (35, 36). Comparative structural analyses will be mainly restricted to two intact heterodimeric TCR crystal structures, namely a human nonliganded immunodominant TCR, LC13 (36, 37), and the nonliganded murine TCR, 2C (38, 39). The root mean square (RMS) for the pairwise superpositions between the NKT12 TCR and the LC13 and 2C TCRs were 1.20 Å (383 residues) and 1.43 Å (345 residues), respectively. As expected, the constant domains of the NKT12 TCR superpose very closely with that of another nonliganded human TCR, LC13 (RMS deviations 0.50 Å and 0.47 Å over the Cα and Cβ domains, respectively). However significant differences in juxtaposition between the Vα and Vβ domains were observed, which reflects the unique interchain pairing of the semi-invariant NKT TCR. For example the Vβ domain of NKT12 is rotated 16.4° and 13.1° relative to the 2C TCR (38, 39) and the LC13 TCR, respectively (36, 37). Moreover, comparative analyses revealed structural divergence within the respective Vα and Vβ domains. For example, pairwise superpositions between NKT12 Vα and the LC13 and 2C Vα domains were 1.40 Å (94 residues) and 1.34 Å (92 residues), respectively; whereas the pairwise superpositions between the Vβ domains (LC13, 1.08 Å [98 residues]; 2C, 1.02 Å [103 residues]) revealed that, in comparison, the Vα domain was more divergent than the Vβ domain. The major structural differences within the V domains reside in the hypervariable loops and the loop (69α-74α), which impacts not only upon the Ag binding site, but also the Vα-Vβ pairing.

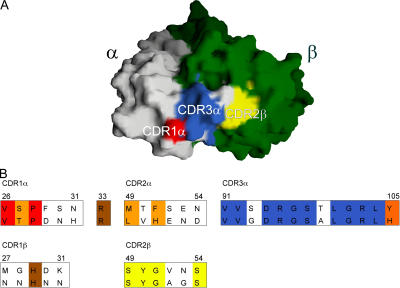

Figure 2.

Overview of NKT cell TCR structure showing the conformation of the CDR loops at the Ag-binding interface. (A) Overview of the structure of NKT12 with the α-chain and β-chain shown in gray and pink, respectively. (B) The CDR3 loops of NKT12 are color coded according to their genetic origin. (C) Superimposition of the CDR loops of the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs depicting the difference in the conformation of CDR3β (NKT12, CDR loops colors are indicated; NKT15, orange).

The NKT12 Vα–Vβ interface is composed of the f-g and the c-c′ strands, and their interconnecting loops from each domain crossing over each other, and accordingly utilizes both the Vα24 and Jα18 gene segment of the invariant chain (Supplemental Materials and methods, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1). The CDR3α and CDR3β loops sit centrally at this interface, abutting each other (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Materials and methods). At the Vα–Vβ interface, there are six polar interactions, five water-mediated polar interactions, two salt bridges, and a multitude of van der Waals interactions that include a cluster of aromatic residues (Tyr35α, Phe106α, Tyr33β, Tyr35β, Tyr107β) (Table S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1). This cluster is largely conserved, although less extensive in the LC13 and 2C TCR structures.

The sequences encoded by the invariant Jα and hypervariable Dβ-N-Jβ region create the CDR3 loops (Fig. 2, A and B). Accordingly, the interface differs slightly between the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs as a result of the conformation of the different CDR3β loops (Fig. 2 C). Notably, the CDR1α and CDR2α loops adopt a conformation that is different from previously determined canonical CDR conformations (40), whereas CDR1β and CDR2β adopt canonical conformations β1-1 and β2-1, respectively (Table S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1). The conformation of the CDR3α loop is well ordered and stabilized by interloop interactions as shown for other highly selected TCRs (34).

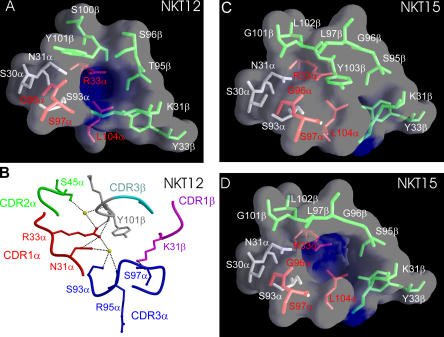

The ligand binding surface contains a preformed cavity suited to Ag binding

The ligand-binding surface of NKT12 contains a central water-filled cavity that is markedly electropositive and ∼120 Å3 in volume (Fig. 3, A and B). The cavity is lined by residues from CDR1α and CDR3α of the invariant NKT α-chain, as well as CDR1β and CDR3β of the semi-invariant β-chain that collectively make several direct and water-mediated interactions with each other (Fig. 3 B). The residues from the invariant Vα24-N-Jα18 include the following: Ser30α and Asn31α from CDR1α; Arg33α from the Vα-framework close to CDR1α; Ser93α from the CDR3α V-J junctional region; and Gly96α, Ser97α, and Leu104α, all from the CDR3α Jα segment. Remarkably, Arg33α that forms the electropositive base of the cavity is unique to Vα24 among all the human Vα genes and is also conserved in mouse Vα14 and in only one other Vα family (TRAV7). Similarly, the Jα residues Gly96α, Ser97α, and Leu104α are only found in Jα18. The Vβ framework residue Tyr33β, adjacent to the CDR1β, also lines the cavity and is conserved in mouse and human NKT Vβ regions. The NKT15 TCR is virtually identical in structure to NKT12, apart from the amino acid sequence and conformation of its CDR3β regions. These differences include two extra residues encoded by the Dβ-N region, thereby introducing a charged, surface-exposed “RDR” motif that forms the tip of CDR3β in the NKT15 TCR. Thus, the hypervariable CDR3β residues that line the cavity of NKT12 include Thr95β, Ser96β, Ser100β, and Tyr101β; whereas, in NKT15, the corresponding residues lining the cavity are Ser95β, Gly96β, Leu97β, and Gly101β (Fig. 3, C and D; Table I). Although the positively charged cavity at the Ag-binding interface is conserved between NKT12 and NKT15, in the trigonal crystal form, the entrance to the cavity is occluded by the bulky Tyr103β (Jβ) from the CDR3β loop of NKT15 (Fig. 3 C). Notably, however, this region of the CDRβ loop is relatively mobile, such that Tyr103β was unresolved in the orthorhombic crystal form. This suggests that Tyr103β could be easily displaced, allowing access of potential ligands to this conserved region (Fig. 3 D). The cavity at the ligand interface could potentially accommodate small polar moieties such as the galactose ring of α-GalCer that projects out of the antigen-binding cleft of CD1d (14, 15) (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1). This would be consistent with a direct interaction between NKT TCRs and the glycosyl head group of α-GalCer bound to CD1d, as predicted from many studies and analogous to what has been proposed for CD1b/glycolipid recognition (41). The volume of the cavity would be predicted to vary according to the structure and flexibility of the CDR3β sequences; this might facilitate interaction with other glycolipid head groups.

Figure 3.

The Ag-binding interface of NTK12 and NKT15 TCRs contains a preformed cavity created by invariant residues of the α-chain, a species-conserved residue from the β-chain and CDR3β. (A) NKT12 TCR α-chain residues that are conserved between human and mouse are red; α-chain residues that differ between these species are gray. The TCR β-chain residue Tyr33β is conserved across species, whereas the CDR3β residues are divergent between species. β-chain side chains are green. (B) Close-up of residues forming the putative ligand-binding cavity of the NKT12 binding surface. Residues are labeled according to the single amino acid code. (C) The putative ligand-binding cavity of NKT15 is obstructed by the bulky side chain of residue Tyr 103β from CDR3β in the trigonal form of the crystal structure. (D) Tyr103β could not be visualized in the NKT15 TCR crystal comprising the orthorhombic space group. The high mobility of Tyr103β could easily allow displacement of this side chain, exposing the putative Ag-binding cavity. Accordingly, the Tyr103β side chain has been omitted, revealing the cavity.

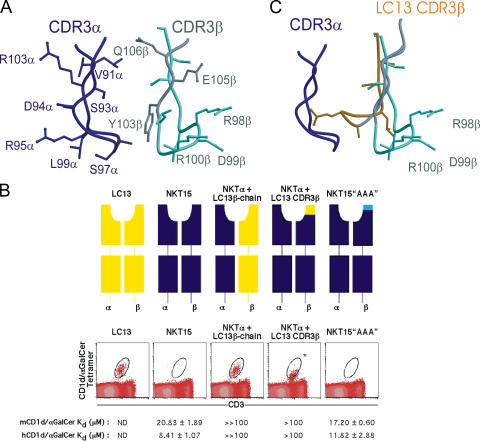

The CDR3β hypervariable loop modulates antigen specificity

Previous studies have shown that mouse Vβ8.2+ NKT TCRs can be substituted with Vβ8+ chains from non–NKT cells without loss of binding affinity to mCD1d/α-GalCer (28), suggesting that the CDR3β region plays little or no role in NKT cell specificity, at least to this antigen complex. However, the structure of the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs showed that some CDR3β residues line parts of the cavity at the ligand interface, where they could modulate Ag specificity. We examined the role of CDR3β by assessing how variation in this region affects cross-species reactivity with CD1d/α-GalCer. We first measured the affinity of NKT12, NKT15, and NKT18 TCRs for α-GalCer complexed to mCD1d and hCD1d using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Table S3 and Fig. S2, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1, and NKT18 not depicted). This allows a direct examination of the impact of the variable CDR3β region on the TCR interaction. The affinity of the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs was approximately twofold higher for hCD1d/α-GalCer (Kd (eq) ∼10 μM) versus mCD1d/α-GalCer (Kd (eq) ∼20 μM), whereas the affinity of the NKT18 TCR was similar for human and mouse CD1d/α-GalCer (Kd (eq) ∼20 μm). Although these affinity differences with mCD1d/α-GalCer were small, they were reproducible, indicating a subtle but measurable influence of CDR3β on NKT TCR specificity.

We next studied the binding of several hybrid TCRs with switched or mutated CDR3β regions (Fig. 4 and Table S4, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1). The native integrity of these chimeric receptors was intact based on their binding with a conformation-dependent mAb 12H8 (34) and their behavior by gel filtration and SDS-PAGE (unpublished data). First, we examined the relative roles of the CDR1β and CDR2β, versus the hypervariable CDR3β residues (encoded by Dβ-N-Jβ gene segments) of NKT15, by swapping the entire NKT15 TCR β-chain for that of the classical MHC I–restricted TCR LC13 (36, 37) (Fig. 4 B). This TCR contains a different Vβ chain (Vβ6.2 or TRBV7-8*03) to NKT15, but uses the same Jβ segment to create the CDR3β loop (TRBD1/D2; TRBJ2-7*01). The hybrid NKT15α/LC13β TCR lost virtually all CD1d/α-GalCer binding as measured by both SPR and by failure to inhibit NKT cell staining by CD1d/α-GalCer tetramer (Fig. 4 B). Although this finding suggests that either CDR1β and/or CDR2β may be crucial for CD1d/α-GalCer binding, it could also be explained by an incompatibility in the LC13 CDR3β region. Therefore, a chimeric TCR was generated where just the CDR3β loop of NKT15 was replaced with the corresponding loop of LC13 (also encoded by Jβ TRBJ2-7) (Fig. 4 B). This swap shortens the CDR3β loop of NKT15 by three residues and alters the sequence of buried amino acids involved in stabilizing the TCR α-chain as well as changing the solvent-exposed residues at the tip of the loop (Table S4). The hybrid TCR had an ∼5–10-fold lower affinity by SPR measurements than NKT15 bound to both human and mouse CD1d/α-GalCer. In addition, the hybrid TCR required ∼60-fold higher concentrations than NKT15 to achieve comparable inhibition of staining of mouse NKT cells with mCD1d/α-GalCer tetramers (Fig. 4 B). However, the structures of the LC13 (36, 37) and NKT15 TCRs suggested that the orientation of the LC13 CDR3β was likely to sterically impact on the conformation of the NKT15 CDR3α loop, thereby indirectly affecting the putative binding cavity and disrupting ligand recognition by the hybrid TCR (Fig. 4 C). Notwithstanding these findings, the CDR3β loops of other NKT TCRs show substantial variation (26, 27, 42), suggesting that sequence variation at the solvent-exposed tips of the CDR3β loops might be well tolerated. To this end, we made a triple alanine mutant in the 98RDR100 sequence (encoded by Dβ-N), which is highly solvent accessible and, as such, their mutation is not predicted to affect the conformation of the CDR3α loop (Fig. 4 A). SPR-binding studies of this “AAA” mutant NKT15 TCR revealed its affinity for both human and mouse CD1d/α-GalCer was comparable to the wild-type NKT15 (Fig. 4 B), indicating these three exposed residues are not critical to the affinity of the interaction. In addition, this hybrid TCR inhibited staining of mouse NKT cells by mCD1d/α-GalCer tetramers at the same concentration as NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

NKT cell receptor CDR3β regions impact on the recognition of CD1d/α-GalCer. (A) Conformation of the CDR3 loops of the NKT15 TCR revealing the highly exposed “RDR” motif at the tip of the CDR3β loop. (B) Inhibition of NKT cell staining by recombinant wild-type and chimeric NKT TCRs. TCRs comprised LC13αβ; NKT15αβ; NKT15α-chain/LC13 β-chain; NKT15α-chain/NKT15 β-chain engrafted with the LC13 CDR3β-loop; and NKT15α-chain/NKT15β-chain with “RDR” to “AAA” substitution within the CDR3β loop. Graded concentrations of soluble recombinant TCRs were preincubated with phycoerythrin-labeled tetramers of mCD1dα-GalCer. These were used to costain mouse thymocyte cells with anti-CD3 mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are flow cytometry plots with tetramer-staining after preincubation with 500 μg/ml TCRs. *, the inhibition observed with maximal concentrations of the NKTα+LC13(CDR3β) (500 μg/ml) was only partial, and equivalent to the inhibition observed with 8 μg/ml (not depicted) of NKT15. The indicated KD values are calculated from SPR studies of TCR binding to immobilized human and mouse CD1dα-GalCer (Table S3 and Fig. S2 for NKT12 and NKT15). LC13 is a control TCR from an HLA-B8–restricted, virus-specific CTL; ND, KD not measurable. (C) Superposition of the CDR3β loop of LC13 in the context of the NKT CDR3α based on the known structure of LC13 (references 36, 37). The LC13 CDR3β loop is predicted to impact on the conformation of CDR3α and to disrupt access to the putative Ag-binding cavity.

Collectively, our data suggest that the function of the CDR3β region is to modulate NKT cell recognition of different glycolipids. Although this modulation of specificity sometimes results in sterically abolishing recognition altogether, as in the substitution of the LC13 CDR3β region in NKT15, the concept is consistent with a high degree of structural variation being tolerated in this region without loss of affinity.

Cross-species reactivity of NKT cells with CD1d/α-GalCer

Unlike the highly restricted recognition of MHC I molecules by conventional αβ TCRs, NKT cell TCRs (including NKT12, 15, and 18) show a remarkable cross-species reactivity, implying evolutionary conservation of an important immune specificity and function (33). The invariant TCR α-chain from human NKT cells has 54% sequence identity with its mouse counterpart, whereas the human Vβ11 and mouse Vβ8.2 share 65% sequence identity. This cross-species identity is particularly marked in the CDR3α and CDR1α loops in which 10/13 and 2/6 residues, respectively, are identical between human and mouse sequences (Fig. 5). Moreover, the two identical residues in the CDR1α are surface exposed. The CDR3α and CDR1α residues that are conserved across species form part of an extensive, contiguous surface at the ligand-binding interface of the NKT TCRs (Fig. 5 A). Based on the mode of recognition of MHC–peptide complexes (35), this region of the TCR would be expected to make interactions with the CD1d–glycolipid complex. In addition, the CDR3α and CDR1α loops make numerous interloop interactions involving residues that are largely conserved between the human and mouse semi-invariant NKT TCRs. These interactions are important in stabilizing the conformation of the CDR loops.

Figure 5.

Conserved residues from human and mouse NKT TCR CDR1α, CDR3α, and CDR2β loops form a contiguous conserved surface that is adjacent to the putative Ag-binding cavity. The different conserved CDR regions are colored to correspond to the sequence alignment of mouse and human CDR loops. All other conserved and semi-conserved residues are brown and orange, respectively, in the alignment and are not shown in the structure. The TcR α-chain is white and the TCR β-chain is green.

Notably, 0/6 of the amino acids in the human and mouse CDR2α loop are identical, although the Phe51 (human) versus His51 (mouse) residues are relatively conserved (Fig. 5 B). This observation is consistent with the natural allelic polymorphism in the mouse Vα14 gene (TRAV11*01 vs. TRAV11*02) in which 3/7 CDR2α residues contain nonconservative substitutions that have minimal impact on TCR affinity for CD1d/α-GalCer (43). These findings suggest a minor role for CDR2α residues in mediating cross-species CD1d reactivity.

In the TCR β-chain, only the CDR2β shows significant sequence identity between mouse and human TCRs that share 4/6 residues at the tip of this loop, and 4 amino-terminal residues (45LIHY48) and 5 carboxy-terminal residues (55TEKGD59) either side of the tip of the loop. Notably, the surface exposed CDR2β loop, and the highly conserved “hot spot” formed by the CDR3α and CDR1α loops merge to create an even more extensive species-conserved region at the ligand interface (Fig. 5). Accordingly, this region of the TCR is likely to play a crucial role in CD1d–glycolipid interactions by mediating restricted recognition and cross-species reactivity. In contrast with the CDR2β loop, the CDR1β loop is only moderately conserved across human and mouse sequences. However, as outlined earlier, there are five further cross-species conserved residues that line the cavity at the ligand interface of the NKT TCR: Tyr33β, Arg33α, Gly96α, Ser97α, and Leu104α.

Collectively, the structures of NKT12 and NKT15 suggest that the species conservation of CDR3α, CDR1α, and CDR2β loops creates a contiguous conserved hot spot. It is highly likely that this hot spot and the collection of conserved residues forming the cavity at the ligand-interface are crucial in mediating the reciprocal cross-species reactivity between human and mouse NKT TCRs.

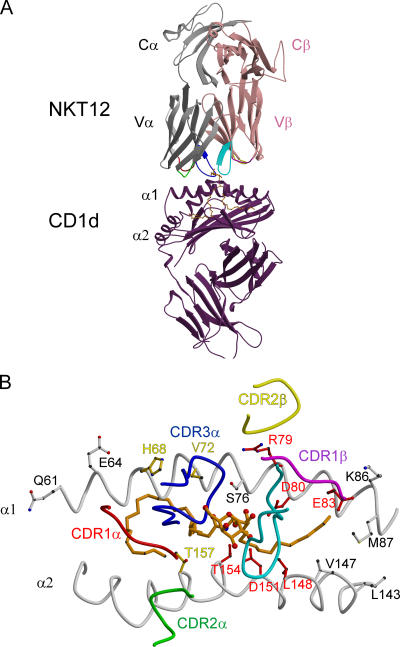

Proposed docking of NKT TCR onto CD1d/α-GalCer

The NKT TCR structure, together with the recently published CD1d/α-GalCer structures and previous mutagenesis experiments, has allowed us to propose a model for the interactions between the NKT TCR and CD1d/α-GalCer. For several reasons, the model was based on the LC13–HLA–B8–FLR complex. First, we examined all the TCR–MHC-I-p complexes solved to date and the LC13 complex provided the best approximation for docking of the central TCR pocket over the α-GalCer head group. Second, like α-GalCer, the peptide determinant recognized by LC13 is a minimally protruding Ag and is similarly located to the glycosyl head group of α-GalCer. Moreover, LC13 also has a central pocket that accommodates the main side chain of the ligand as proposed for NKT TCRs. Despite the known caveats of any structural estimation, the model provides plausible insight into NKT TCR recognition of hCD1d/α-GalCer and is consistent with several published observations. Thus, in both the mouse and human CD1d molecules, the conserved residues Arg79, Asp80, Glu83, and Asp153 (Asp 151 in hCD1d) are critical for presentation of α-GalCer by CD1d (44). Of these amino acids, Arg79 and Asp153, but not Glu83, make interactions with α-GalCer (14, 15). However, mutagenesis studies suggest that all three can influence recognition by the NKT TCRs (17, 44, 45), perhaps directly or by affecting the orientation of the α-GalCer glycosyl head group. Taking these issues into consideration, the model is consistent with diagonal docking of the NKT TCR over the ligand-binding domain of CD1d (Fig. 6). Because α-GalCer protrudes only minimally from the CD1d cleft, the NKT TCR forms considerable contacts with CD1d. Thus, the CDR1α and CDR2α loops are primarily positioned over the α2 helix, interacting with hCD1d residues spanning Trp153–Trp160. The aromatic residue Phe51α (His51 in mouse), located within the CDR2α loop, could potentially stack neatly between the two bulky aromatic rings of Trp153 and Trp160 of hCD1d. The CDR1β and CDR2β loops docks over the α1 helix of CD1d, interacting with a localized stretch of CD1d residues (75–83). Although CDR2β is located on the periphery, our model suggests that the prominent Tyr48β packs against Ser75 and the aliphatic moiety of Arg79 in CD1d. Moreover, our model suggests a potential salt bridge between Arg79 and Asp30β of the CDR1β loop. This is consistent with a role for Arg79 independent of its interactions with α-GalCer, as an important residue for recognition of CD1d/α-GalCer by many NKT TCRs. Notably, however, substitution of this residue can be tolerated by certain NKT cells indicating a variable contribution of Arg79 contingent upon the nature of the glycolipid Ag (44). The conserved TCR residues Asp94α, Arg95α, and Arg103α are solvent exposed and proximal to the binding interface cavity, where their charged nature provides the potential for complementary electrostatic interactions with one or more of these CD1d residues.

Figure 6.

Proposed docking of NKT TCR onto CD1d/α-GalCer. (A) In the model, the NKT12 α and β chain are shown in gray and pink, respectively, and the CDR loops are red (CDR1α), green (CDR2α), blue (CDR3α), magenta (CDR1β), yellow (CDR2β), and cyan (CDR3β). α-galactosylceramide is shown in orange within the antigen-binding domain of hCD1d (purple). (B) View of the antigen-binding cleft of human CD1d–presenting α-GalCer (orange). The CDR footprint of the proposed docking model of NKT12 is shown for reference and the CDR loops are colored as in A. Surface-exposed residues on the α1 and α2 helices of hCD1d are shown. Residues in red had an impact on NKT activation by mCD1d in the published literature. Residues in white either had no impact or were not investigated. Residues in yellow are those residues likely to be important in the docking of NKT12 onto CD1d/α-galactosylceramide according to our proposed model.

Both the CDR3α and CDR3β loops make contact with the galactose moiety of α-GalCer in the model; however, the CDR3α loop is also predicted to interact extensively with the α1 helix (spanning residues 65–72) of CD1d. Thus, the conserved residues within the CDR3α loop are proposed to mediate interactions with conserved residues on CD1d accounting for the inherent bias of this TCR in ligating CD1d. The prominent role of CDR3α in interacting with CD1d may explain NKT cross-reactivity between mouse and human CD1d, analogous to the way that the CDR3α loop of the LC13 TCR is suggested to dictate its known alloreactivity (34).

Upon ligation, the surface-exposed galactose of α-GalCer is “walled” by the CDR3α and CDR3β loops such that the galactose is positioned within the electropositive preformed cavity. The galactose head group of α-GalCer is likely to interact with residues lining the pocket, including Asn31α, Arg33α, Gly96α, Ser97α, and Lys31β. The role of Arg33α may involve specificity interactions analogous to those observed in the LC13 TCR binding pocket, where His33α at the base of the pocket makes a water-mediated bond to a critical peptide side-chain from the ligand (37).

Larger Ag headgroups, such as the tri-hexosyl moiety of the glycosphingolipid iGb3 (7, 8), are likely to be partially accommodated via movement in the CDR3 loops. This is consistent with the observed plasticity of αβTCRs in engaging with pMHC molecules. We predict that the flexible CDR3β loop will allow modulation of NKT cell recognition of different glycolipids. Therefore, the extent of the preformed cavity volume is likely to change, depending on the position of the CDR3β loop. This is consistent with a high degree of structural variation being tolerated in this region without loss of affinity to ligands such as α-GalCer.

DISCUSSION

NKT cells straddle the roles of both innate and adaptive cellular immune responses (46). They respond rapidly upon antigen recognition by their semi-invariant TCR, producing a variety of cytokines that can regulate tumor immunity, autoimmunity, and allergy and can orchestrate protective responses to infectious agents (2, 47–49). Despite expressing a semi-invariant TCR, NKT cells are reported to be selected or activated by different glycolipid molecules such as the marine sponge-derived α-GalCer (6), a phosphoethanolamine (50), PIM4 (11), α-glycuronosyl-ceramides (8–10, 51, 52), sulfated variants thereof (10), a tumor-derived ganglioside GD3 (31), self-antigens including some forms of β-galactosylceramide (53, 54), and isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) (7). This capacity to recognize a variety of foreign and self-derived glycolipid Ags reflects the increasingly diverse functional roles ascribed to NKT cells (47–49) and highlights the need for a structural explanation as to how the semi-invariant NKT TCR can achieve such a diversity of recognition. Abundant evidence suggests that the glycosyl head group of the glycolipid sugar moiety is a critical determinant recognized by the NKT TCR (14–16, 29, 44, 45, 55, 56). Thus, the NKT TCR binds efficiently to CD1d complexed with α-GalCer but not with β-GalCer containing similar sphingosine and acyl chains (56), consistent with the lipid chains being buried in the Ag-binding cavity, whereas the glycosyl head group protrudes out of the cleft (14, 15). It is notable that the small target created by the polar head of α-GalCer induces a highly selected “immunodominant” αβ TCR repertoire. This bias is reminiscent of the highly restricted CTL repertoires toward minimally exposed (36, 57, 58) or highly unusual viral determinants (59–61).

These observations would be consistent with the cavity at the ligand interface of the NKT12 and NKT15 TCRs acting as a preformed Ag pocket. The structures of CD1d/αGalCer have led to speculation that the CDR3α of the NKT TCR would be placed over the galactose ring (14). This mode of interaction fits the idea that the cavity might envelope the polar glycosyl head group of α-GalCer and some related antigens. Supporting this interpretation, the walls of the cavity are formed from unique amino acids present in the Vα-domain (CDR1α and Arg33α) and CDR3α regions of the invariant TCR α-chain. Moreover, these regions are highly conserved between mouse and human NKT TCRs that are functionally cross-reactive (62). In addition, CDR1β and CDR3β residues also contribute to the cavity wall, providing a mechanism by which the CDR3β could modulate Ag specificity. Many studies have reported heterogeneous CDR3β usage by NKT cells, suggesting that these loops do not play a key role in NKT cell recognition (25–28). However, our data indicate that not all CDR3β sequences support recognition of CD1d–glycolipid complexes and this is probably the result of steric hindrance by some CDR3β loops that obstruct the cavity interface and/or interfere with the conformation of the highly conserved CDR3α loops.

The binding kinetics and affinities of the human NKT12, NKT15, and NKT18 TCRs for hCD1d/α-GalCer are typical of conventional αβTCR–MHCp interactions with KD values of ∼8–20 μM. This contrasts with the high affinity binding of recombinant mouse NKT TCRs, where the KD values are reported to be ∼0.1–0.3 μM (28, 45). These differences presumably reflect species variability despite the remarkable reciprocal cross-reactivity of human and mouse NKT cells. This cross-reactivity correlates with a conserved hot spot at the NKT TCR interface that comprises a contiguous surface suitable for interacting with CD1d–glycolipid complexes. Additional conserved residues forming the cavity at the ligand interface are also likely to contribute to the reciprocal cross-species reactivity. Despite the cross-species interactions, the glycosyl head group of α-GalCer is shifted by up to 3 Å between the mouse and human structures, which is likely to impact on the recognition of the galactose moiety itself (63). Human CD1d has a tryptophan residue at position 153 that pushes the galactose head group away, whereas, in mouse, the equivalent amino acid (position 155) is a much smaller glycine residue (14, 15). The previously reported lack of temperature dependence in the binding affinity of mouse NKT TCRs with CD1d-αGalCer suggests a rigid “lock and key” mode of binding (28, 56). However, the cross-reactivity of human and mouse NKT TCR for CD1d–α-GalCer implies that NKT TCR recognition has considerable structural plasticity more typical of αβTCR–MHC-I interactions and potentially important in the recognition of different glycolipid antigens.

How can NKT cells, with a semi-invariant TCR, recognize a diversity of glycolipid antigens with structurally distinct carbohydrate head groups? Although this can only be definitively answered with direct structural studies, the recently defined α-glucuronosylceramides (8–10, 51, 52) are structurally very similar to α-GalCer and α-glucosylceramide and thus conceivably would fit into the same TCR cavity. It is also possible, or even likely, that only a minor subset of fresh human NKT cells recognize some of these more recently defined antigens. For example, <10% of NKT cells were labeled by PIM4-loaded CD1d tetramers (11) and the labeling was 10–100-fold weaker than for α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramers. Similarly, although in mice most NKT cells depend on iGb3 for thymic selection (7), it is not proven that iGb3 is a key selecting ligand for human NKT cells (64). Moreover, given that mouse NKT cells do not stain with CD1d/iGb3 tetramers (7), their affinity for NKT TCRs is likely to be very low, suggesting that the tri-hexosyl head group of this Ag might be poorly recognized in comparison to the galactosyl head group of α-GalCer. Furthermore, the extent to which fresh human NKT cells recognize other glycolipid ligands such as GD3 (31) and phosphoethanolamine (50) is unknown. Notwithstanding these concerns, it is not inconceivable that different sugar groups could be accommodated within the pocket by a degree of plasticity in the CDR3 loops and in particular the CDR3β loop, which was shown to exhibit a degree of flexibility in our study.

Collectively, our findings suggest a basis for the semi-invariant nature of NKT TCRs in which highly conserved residues in the α- and β-chains of the TCR contribute to binding of glycolipid head groups through a discrete cavity at the ligand interface. Other conserved features of the NKT TCR appear to play a role in CD1d binding, whereas plasticity of antigen recognition is preserved through variation in CDR3β loops and the intrinsic adaptability of other CDR loops at the ligand interface. Furthermore, our proposed model of the complex suggests that the CDR3α loop plays a prominent role in determining Ag specificity as well as dictating the observed cross-species reactivity via interactions with CD1d. It will be intriguing to visualize this plasticity in complexes of NKT TCRs with a variety of CD1d/glycolipid antigens and to correlate the modes of interaction with functional diversity in NKT cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression, refolding, and purification.

cDNAs encoding NKT cell receptors and CD1d were derived as described in the Supplemental Materials and methods. Inclusion body protein of the NKT TCRα and NKT TCRβ chains were prepared essentially as described previously (36, 37, 65). 64 mg TCRα and 32 mg TCRβ inclusion body proteins were thawed, pulsed with 1 mM DTT, combined, and injected into 800 ml of stirring refolding buffer containing 100 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 5 M urea, 0.4 M arginine, 0.5 mM oxidized glutathione, 5 mM reduced glutathione, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 1 μg/ml Pepstatin A at 4°C. Equal amounts of the NKT TCRα and NKT TCRβ chain inclusion body proteins were added 16 h later. After 24 h, refolded protein was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 M urea, pH 8, and subsequently against 10 mM Tris-HCl. Dialyzed protein was captured on a column containing DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare), and eluted with 10 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl. Eluted NKT TCR was concentrated and loaded unto a HiLoad Superdex 75 pg gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) in the presence of 10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl. Fractions containing the TCR were pooled and purified further on a Mono-Q column (GE Healthcare). Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated before one more purification by gel filtration as described earlier in this paragraph. Peak fractions were concentrated to 10–20 mg/ml and were used subsequently in crystal trials.

Crystallization.

Rod-shaped crystals of the NKT TCRs were grown at 12 mg/ml by the hanging drop vapor diffusion technique and at room temperature. NKT12 crystals grew in 18% PEG 3350, 0.1 M cacodylate, pH 6.3, 0.2 M lithium chloride, and NKT15 crystals grew in 9% PEG 3350, 0.1 M cacodylate, pH 6.4, 0.2 M ammonium acetate. The crystals belong to space group C2221 and the unit cell dimensions were consistent with one molecule per asymmetric unit (Table II). NKT15 crystals were also grown in 0.2 M sodium sulfate. 20% PEG 3350, pH 6.6. These crystals belong to space group P32, with unit cell dimensions consistent with two molecules per asymmetric unit (Table II).

Structure determination and refinement.

The crystals were flash frozen before data collection using up to 15% glycerol as the cryoprotectant. The data were processed and scaled using the HKL package. Datasets of 2.2, 2.4, and 2.6 Å resolution were collected at the BioCars beamline using a Quantum 4 CCD detector (Table II). The crystal structures were solved using the molecular replacement method, as implemented in MOLREP (66), using the unliganded LC13 (37) structure as the search model, where the LC13 CDR loops were initially removed and all other nonidentical residues were mutated to alanine. Unbiased features in the initial electron density map confirmed the correctness of the molecular replacement solution. The progress of refinement was monitored by the Rfree value with neither a sigma, nor a low resolution cut off being applied to the data. Initially, the structures were refined using rigid-body fitting of the individual domains followed by the simulated-annealing protocol implemented in CNS (version 1.0) (67). Later, translation, libration, and screw-rotation displacement (TLS) refinement was performed using REFMAC (68). Refinement was interspersed with rounds of model building using the program “O” (69). Tightly restrained individual B-factor refinement was used, and bulk solvent corrections were applied to the data set. Water molecules were included in the model if they were within hydrogen-bonding distance to chemically reasonable groups, appeared in F o − F c maps contoured at 3.5σ, and had a B-factor of <60 Å2. The structures have been deposited in the PDB (accession nos. 2EYR, 2EYS, 2EYT).

Biotinylation of CD1d and loading with α-GalCer.

Biotinylated CD1d was mixed with α-GalCer at a molar ratio of 1:3 (protein:lipid) at room temperature overnight. Loaded CD1d protein was then purified from free α-GalCer and buffer exchanged into 10 mM Hepes-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.005% surfactant P20 using a HiLoad Superdex 200 pg gel filtration column (GE Healthcare). Protein quality was monitored by its gel filtration profile and mobility on SDS-PAGE.

SPR binding studies.

All SPR experiments were conducted at 25°C on a Biacore 3000 instrument using HBS buffer (10 mM Hepes-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.005% surfactant P20 supplied by the manufacturer) supplemented with 1% BSA. Approximately 2,000–3,000 RU of α-GalCer–loaded human and mouse CD1d was immobilized onto streptavidin-coupled sensor chip (BiaCore). Corresponding levels of “unloaded” CD1d were also immobilized to act as controls. Equilibrium affinity was determined by injecting increasing concentrations of NKT TCR over all flow cells at 5 μl/min for 3 min. The final response was calculated by subtracting the response of the “unloaded” CD1d surface from the α-GalCer CD1d surface. BIAevaluation version 3.1 (Biacore AB) was used to fit the equilibrium data.

CD1d/α-GalCer tetramer inhibition assay and flow cytometry.

Anti-CD3–FITC (clone 145-2C11) was purchased from BD Biosciences. Fc-receptor block (anti-CD16/CD32, clone 2.4G2) was added to all staining cocktails. Mouse CD1d tetramer loaded with α-GalCer was produced as described previously (70). CD1d/α-GalCer tetramer was incubated with serially diluted (twofold dilutions from 500 μg/ml to 4 μg/ml) soluble human NKT cell TCR or an irrelevant TCR (LC13) control. Thymic cell suspensions were made by gently grinding the organ between the frosted ends of glass microscope slides in ice-cold PBS containing 2% FCS (FACS buffer). Cell suspensions were passed through 100 μm mesh before antibody staining. Equivalent inhibition of staining of thymocytes with CD1d/α-GalCer tetramers was observed with NKT12, NKT15, NKT18, and NKT15‘AAA’ TCRs, and inhibition with these NKT TCRs was diminished equally upon dilution. Thymocytes were stained with anti-CD3 mAb, washed with FACS buffer, and stained with the CD1d/α-GalCer tetramer–TCR mixtures. Cells were washed with FACS buffer to remove any unbound CD1d/α-GalCer tetramer and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Modelling of the NKT TCR–CD1d–α-GalCer complex.

The docking of NKT12 onto hCD1d was approximated in the following way. The MHC of each of the MHC–peptide–TCR complex structures available in the PDB was aligned onto the CD1d antigen-binding domain (residues 61–86 and 139–171). The TCRs from each of the complexes were examined for clashes with the helices of hCD1d and the α-GalCer. The TCR with the best fit over CD1d/α-GalCer was LC13 (PDB code: 1MI5) and so the Cα domain of LC13 was used to superpose NKT12 in the final CD1d–α-GalCer–NKT12 model. NKT12 was adjusted manually using the program “O” to promote a better fit for our proposed model.

Online supplemental material.

Supplemental Materials and methods for cDNA cloning of NKT TCRs and CD1d are provided. Table S1 provides contacts at the Vα–Vβ interface of NKT12 and the genetic origin of TCR residues. Table S2 describes the Phi psi torsion angles of CDR1 and CDR2 in NKT12. Table S3 describes the dissociation constants of natural and mutated NKT TCRs with CD1d/α-GalCer. Table S4 gives the amino acid sequences of CDR3β residues in natural and mutated NKT TCRs. Fig. S1 models the Ag-binding cavity of the NKT TCR to demonstrate how this can accommodate the galactose head group of α-GalCer. Fig. S2 shows the SPR sensorgrams and affinity estimations of NKT12 binding to immobilized hCD1d-GalCer and mCD1d-GalCer. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20051777/DC1.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Berzins for help in generating the NKT cell lines. We thank the staff at BioCARS and the Australian Synchrotron Research Program for assistance.

J. Rossjohn is supported by an Australian Research Council Professorial Fellowship and N.A. Borg, T. Beddoe, D.I. Godfrey, and M.J. Smyth are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Research Fellowships. G.S. Besra, a Lister-Institute-Jenner Research Fellow, acknowledges support from The Medical Research Council (grant nos. G9901077 and G0400421) and The Wellcome Trust (grant no. 072021/Z/03/Z). This work was also supported in part by the NHMRC Australia, the Australian Research Council, the Cancer Council Victoria, and the Roche Organ Transplantation Research Foundation.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: α-GalCer, α-galactosylceramide; Ag, antigen; BSA, buried surface area; C, constant; CDR, complementarity-determining region; hCD1d, human CD1d; mCD1d, mouse CD1d; RMS, root mean square; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; V, variable.

L. Kjer-Nielsen and N.A. Borg contributed equally to this work.

J. McCluskey and J. Rossjohn contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ulrichs, T., and S.A. Porcelli. 2000. CD1 proteins: targets of T cell recognition in innate and adaptive immunity. Rev. Immunogenet. 2:416–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigl, M., and M.B. Brenner. 2004. CD1: antigen presentation and T cell function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:817–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi, E., K. Motoki, T. Uchida, H. Fukushima, and Y. Koezuka. 1995. Krn7000, a novel immunomodulator, and its antitumor activities. Oncol. Res. 7:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen, D.S., M.A. Siomos, L. Buckingham, A.A. Scalzo, and L. Schofield. 2003. Regulation of murine cerebral malaria pathogenesis by CD1d-restricted NKT cells and the natural killer complex. Immunity. 18:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schofield, L., M.J. McConville, D. Hansen, A.S. Campbell, B. Fraser-Reid, M.J. Grusby, and S.D. Tachado. 1999. CD1d-restricted immunoglobulin G formation to GPI-anchored antigens mediated by NKT cells. Science. 283:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano, T., J.Q. Cui, Y. Koezuka, I. Toura, Y. Kaneko, K. Motoki, H. Ueno, R. Nakagawa, H. Sato, E. Kondo, et al. 1997. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Vα14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 278:1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou, D., J. Mattner, C. Cantu III, N. Schrantz, N. Yin, Y. Gao, Y. Sagiv, K. Hudspeth, Y.P. Wu, T. Yamashita, et al. 2004. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 306:1786–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattner, J., K.L. Debord, N. Ismail, R.D. Goff, C. Cantu III, D. Zhou, P. Saint-Mezard, V. Wang, Y. Gao, N. Yin, et al. 2005. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 434:525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinjo, Y., D. Wu, G. Kim, G.W. Xing, M.A. Poles, D.D. Ho, M. Tsuji, K. Kawahara, C.H. Wong, and M. Kronenberg. 2005. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 434:520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu, D., G.W. Xing, M.A. Poles, A. Horowitz, Y. Kinjo, B. Sullivan, V. Bodmer-Narkevitch, O. Plettenburg, M. Kronenberg, M. Tsuji, et al. 2005. Bacterial glycolipids and analogs as antigens for CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, K., E. Scotet, M. Niemeyer, H. Koebernick, J. Zerrahn, S. Maillet, R. Hurwitz, M. Kursar, M. Bonneville, S.H. Kaufmann, and U.E. Schaible. 2004. Mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol mannoside is a natural antigen for CD1d-restricted T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:10685–10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano, T., Y. Tanaka, E. Shimizu, Y. Kaneko, N. Kamata, H. Sato, H. Osada, S. Sekiya, T. Nakayama, and M. Taniguchi. 1999. A novel recognition motif of human NKT antigen receptor for a glycolipid ligand. Int. Immunol. 11:881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burdin, N., L. Brossay, Y. Koezuka, S.T. Smiley, M.J. Grusby, M. Gui, M. Taniguchi, K. Hayakawa, and M. Kronenberg. 1998. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: α-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates Vα14+ NK T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 161:3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zajonc, D.M., C. Cantu, J. Mattner, D. Zhou, P.B. Savage, A. Bendelac, I.A. Wilson, and L.D. Teyton. 2005. Structure and function of a potent agonist for the semi-invariant natural killer T cell receptor. Nat. Immunol. 6:810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch, M., V.S. Stronge, D. Shepherd, S.D. Gadola, B. Mathew, G. Ritter, A.R. Fersht, G.S. Besra, R.R. Schmidt, E.Y. Jones, and V. Cerundolo. 2005. The crystal structure of human CD1d with and without α-galactosylceramide. Nat. Immunol. 6:819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant, E.P., M. Degano, J.P. Rosat, S. Stenger, R.L. Modlin, I.A. Wilson, S.A. Porcelli, and M.B. Brenner. 1999. Molecular recognition of lipid antigens by T cell receptors. J. Exp. Med. 189:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porcelli, S., C.E. Yockey, M.B. Brenner, and S.P. Balk. 1993. Analysis of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) expression by human peripheral blood CD4-8-α/β T cells demonstrates preferential use of several V β genes and an invariant TCR α chain. J. Exp. Med. 178:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lantz, O., and A. Bendelac. 1994. An invariant T cell receptor α chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I–specific CD4+ and CD4−8− T cells in mice and humans. J. Exp. Med. 180:1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellabona, P., E. Padovan, G. Casorati, M. Brockhaus, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1994. An invariant Vα 24-JαQ/Vβ11 T cell receptor is expressed in all individuals by clonally expanded CD4−8− T cells. J. Exp. Med. 180:1171–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefranc, M.P. 2001. IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics database. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:207–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emoto, M., Y. Emoto, and S.H. Kaufmann. 1995. IL-4 producing CD4+ TCR αβ int liver lymphocytes: influence of thymus, β2-microglobulin and NK 1.1 expression. Int. Immunol. 7:1729–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bendelac, A., M.N. Rivera, S.H. Park, and J.H. Roark. 1997. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:535–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui, J., T. Shin, T. Kawano, H. Sato, E. Kondo, I. Toura, Y. Kaneko, H. Koseki, M. Kanno, and M. Taniguchi. 1997. Requirement for Vα14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 278:1623–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumann, J., R.B. Voyle, B.Y. Wei, and H.R. MacDonald. 2003. Cutting edge: influence of the TCR Vβ domain on the avidity of CD1d:α-galactosylceramide binding by invariant Vα14 NKT cells. J. Immunol. 170:5815–5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda, J.L., L. Gapin, N. Fazilleau, K. Warren, O.V. Naidenko, and M. Kronenberg. 2001. Natural killer T cells reactive to a single glycolipid exhibit a highly diverse T cell receptor β repertoire and small clone size. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12636–12641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronet, C., M. Mempel, N. Thieblemont, A. Lehuen, P. Kourilsky, and G. Gachelin. 2001. Role of the complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) of the TCR-β chains associated with the Vα14 semi-invariant TCR α-chain in the selection of CD4(+) NK T cells. J. Immunol. 166:1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porcelli, S., D. Gerdes, A.M. Fertig, and S.P. Balk. 1996. Human T cells expressing an invariant Vα 24-JαQ TCRα are CD4− and heterogeneous with respect to TCR β expression. Hum. Immunol. 48:63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantu, C., III, K. Benlagha, P.B. Savage, A. Bendelac, and L. Teyton. 2003. The paradox of immune molecular recognition of α-galactosylceramide: low affinity, low specificity for CD1d, high affinity for αβ TCRs. J. Immunol. 170:4673–4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burdin, N., L. Brossay, M. Degano, H. Iijima, M. Gui, I.A. Wilson, and M. Kronenberg. 2000. Structural requirements for antigen presentation by mouse CD 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:10156–10161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gui, M., J. Li, L.J. Wen, R.R. Hardy, and K. Hayakawa. 2001. TCR β chain influences but does not solely control autoreactivity of Vα14J281 T cells. J. Immunol. 167:6239–6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu, D.Y., N.H. Segal, S. Sidobre, M. Kronenberg, and P.B. Chapman. 2003. Cross-presentation of disialoganglioside GD3 to natural killer T cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benlagha, K., A. Weiss, A. Beavis, L. Teyton, and A. Bendelac. 2000. In vivo identification of glycolipid antigen-specific T cells using fluorescent CD1d tetramers. J. Exp. Med. 191:1895–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brossay, L., M. Chioda, N. Burdin, Y. Koezuka, G. Casorati, P. Dellabona, and M. Kronenberg. 1998. CD1d-mediated recognition of an α-galactosylceramide by natural killer T cells is highly conserved through mammalian evolution. J. Exp. Med. 188:1521–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borg, N.A., L.K. Ely, T. Beddoe, W.A. Macdonald, H.H. Reid, C.S. Clements, A.W. Purcell, L. Kjer-Nielsen, J.J. Miles, S.R. Burrows, et al. 2005. The CDR3 regions of an immunodominant T cell receptor dictate the ‘energetic landscape’ of peptide-MHC recognition. Nat. Immunol. 6:171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudolph, M.G., and I.A. Wilson. 2002. The specificity of TCR/pMHC interaction. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kjer-Nielsen, L., C.S. Clements, A.W. Purcell, A.G. Brooks, J.C. Whisstock, S.R. Burrows, J. McCluskey, and J. Rossjohn. 2003. A structural basis for the selection of dominant αβ T cell receptors in antiviral immunity. Immunity. 18:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kjer-Nielsen, L., C.S. Clements, A.G. Brooks, A.W. Purcell, J. McCluskey, and J. Rossjohn. 2002. The 1.5 Å crystal structure of a highly selected antiviral T cell receptor provides evidence for a structural basis of immunodominance. Structure. 10:1521–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia, K.C., M. Degano, L.R. Pease, M. Huang, P.A. Peterson, L. Teyton, and I.A. Wilson. 1998. Structural basis of plasticity in T cell receptor recognition of a self peptide-MHC antigen. Science. 279:1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia, K.C., M. Degano, R.L. Stanfield, A. Brunmark, M.R. Jackson, P.A. Peterson, L. Teyton, and I.A. Wilson. 1996. An αβ T cell receptor structure at 2.5 Å and its orientation in the TCR-MHC complex. Science. 274:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Lazikani, B., A.M. Lesk, and C. Chothia. 2000. Canonical structures for the hypervariable regions of T cell αβ receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 295:979–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant, E.P., E.M. Beckman, S.M. Behar, M. Degano, D. Frederique, G.S. Besra, I.A. Wilson, S.A. Porcelli, S.T. Furlong, and M.B. Brenner. 2002. Fine specificity of TCR complementarity-determining region residues and lipid antigen hydrophilic moieties in the recognition of a CD1-lipid complex. J. Immunol. 168:3933–3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Exley, M., J. Garcia, S.P. Balk, and S. Porcelli. 1997. Requirements for CD1d recognition by human invariant Vα24+ CD4−CD8− T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sim, B.C., K. Holmberg, S. Sidobre, O. Naidenko, N. Niederberger, S.D. Marine, M. Kronenberg, and N.R. Gascoigne. 2003. Surprisingly minor influence of TRAV11 (Vα14) polymorphism on NK T-receptor mCD1/α-galactosylceramide binding kinetics. Immunogenetics. 54:874–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamada, N., H. Iijima, K. Kimura, M. Harada, E. Shimizu, S. Motohashi, T. Kawano, H. Shinkai, T. Nakayama, T. Sakai, et al. 2001. Crucial amino acid residues of mouse CD1d for glycolipid ligand presentation to Vα14NKT cells. Int. Immunol. 13:853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sidobre, S., O.V. Naidenko, B.C. Sim, N.R.J. Gascoigne, K.C. Garcia, and M. Kronenberg. 2002. The Vα14 NKT cell TCR exhibits high-affinity binding to a glycolipid/CD1d complex. J. Immunol. 169:1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taniguchi, M., K. Seino, and T. Nakayama. 2003. The NKT cell system: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 4:1164–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benlagha, K., and A. Bendelac. 2000. CD1d-restricted mouse Vα14 and human Vα24 T cells: lymphocytes of innate immunity. Semin. Immunol. 12:537–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Godfrey, D.I., and M. Kronenberg. 2004. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J. Clin. Invest. 114:1379–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kronenberg, M. 2005. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:877–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rauch, J., J. Gumperz, C. Robinson, M. Skold, C. Roy, D.C. Young, M. Lafleur, D.B. Moody, M.B. Brenner, C.E. Costello, and S.M. Behar. 2003. Structural features of the acyl chain determine self-phospholipid antigen recognition by a CD1d-restricted invariant NKT (iNKT) cell. J. Biol. Chem. 278:47508–47515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kronenberg, M., and Y. Kinjo. 2005. Infection, autoimmunity, and glycolipids: T cells detect microbes through self-recognition. Immunity. 22:657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sriram, V., W. Du, J. Gervay-Hague, and R.R. Brutkiewicz. 2005. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:1692–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ortaldo, J.R., H.A. Young, R.T. Winkler-Pickett, E.W. Bere Jr., W.J. Murphy, and R.H. Wiltrout. 2004. Dissociation of NKT stimulation, cytokine induction, and NK activation in vivo by the use of distinct TCR-binding ceramides. J. Immunol. 172:943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parekh, V.V., A.K. Singh, M.T. Wilson, D. Olivares-Villagomez, J.S. Bezbradica, H. Inazawa, H. Ehara, T. Sakai, I. Serizawa, L. Wu, et al. 2004. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the in vivo response of NKT cells to distinct α- and β-anomeric glycolipids. J. Immunol. 173:3693–3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brossay, L., O. Naidenko, N. Burdin, J. Matsuda, T. Sakai, and M. Kronenberg. 1998. Structural requirements for galactosylceramide recognition by CD1-restricted NK T cells. J. Immunol. 161:5124–5128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidobre, S., K.J. Hammond, L. Benazet-Sidobre, S.D. Maltsev, S.K. Richardson, R.M. Ndonye, A.R. Howell, T. Sakai, G.S. Besra, S.A. Porcelli, and M. Kronenberg. 2004. The T cell antigen receptor expressed by Vα14i NKT cells has a unique mode of glycosphingolipid antigen recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:12254–12259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stewart-Jones, G.B., A.J. McMichael, J.I. Bell, D.I. Stuart, and E.Y. Jones. 2003. A structural basis for immunodominant human T cell receptor recognition. Nat. Immunol. 4:657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turner, S.J., K. Kedzierska, H. Komodromou, N.L. La Gruta, M.A. Dunstone, A.I. Webb, R. Webby, H. Walden, W. Xie, J. McCluskey, et al. 2005. Lack of prominent peptide-major histocompatibility complex features limits repertoire diversity in virus-specific CD8+ T cell populations. Nat. Immunol. 6:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tynan, F.E., S.R. Burrows, A.M. Buckle, C.S. Clements, N.A. Borg, J.J. Miles, T. Beddoe, J.C. Whisstock, M.C. Wilce, S.L. Silins, et al. 2005. T cell receptor recognition of a ‘super-bulged’ major histocompatibility complex class I-bound peptide. Nat. Immunol. 6:1114–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miles, J.J., D. Elhassen, N.A. Borg, S.L. Silins, F.E. Tynan, J.M. Burrows, A.W. Purcell, L. Kjer-Nielsen, J. Rossjohn, S.R. Burrows, and J. McCluskey. 2005. CTL recognition of a bulged viral peptide involves biased TCR selection. J. Immunol. 175:3826–3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tynan, F.E., N.A. Borg, J.J. Miles, T. Beddoe, D. El-Hassen, S.L. Silins, W.J. van Zuylen, A.W. Purcell, L. Kjer-Nielsen, J. McCluskey, et al. 2005. High resolution structures of highly bulged viral epitopes bound to major histocompatibility complex class I. Implications for T-cell receptor engagement and T-cell immunodominance. J. Biol. Chem. 280:23900–23909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Capone, M., D. Cantarella, J. Schumann, O.V. Naidenko, C. Garavaglia, F. Beermann, M. Kronenberg, P. Dellabona, H.R. MacDonald, and G. Casorati. 2003. Human invariant Vα24-JαQ TCR supports the development of CD1d-dependent NK 1.1+ and NK 1.1− T cells in transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 170:2390–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Godfrey, D.I., J. McCluskey, and J. Rossjohn. 2005. CD1d antigen presentation: treats for NKT cells. Nat. Immunol. 6:754–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Godfrey, D.I., D.G. Pellicci, and M.J. Smyth. 2004. Immunology. The elusive NKT cell antigen–is the search over? Science. 306:1687–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clements, C.S., L. Kjer-Nielsen, W.A. MacDonald, A.G. Brooks, A.W. Purcell, J. McCluskey, and J. Rossjohn. 2002. The production, purification and crystallization of a soluble heterodimeric form of a highly selected T-cell receptor in its unliganded and liganded state. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58:2131–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vagin, A., and A. Teplyakov. 2000. An approach to multi-copy search in molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56:1622–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunger, A.T., P.D. Adams, G.M. Clore, W.L. DeLano, P. Gros, R.W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J.S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N.S. Pannu, et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murshudov, G.N., and M.Z. Papiz. 2003. Macromolecular TLS refinement in REFMAC at moderate resolutions. Methods Enzymol. 374:300–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones, T.A., J.Y. Zou, S.W. Cowan, and M. Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for building models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta. Crystallogr. A. 47:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matsuda, J.L., O.V. Naidenko, L. Gapin, T. Nakayama, M. Taniguchi, C.R. Wang, Y. Koezuka, and M. Kronenberg. 2000. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J. Exp. Med. 192:741–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.