Abstract

We recently reported two nonsteroidal androgen receptor (AR) ligands that demonstrate tissue-selective pharmacological activity, identifying these S-3-(phenoxy)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-propionamide analogs as the first members of a new class of drugs known as selective androgen receptor modulators. The purpose of these studies was to explore additional structure-activity relationships of selective androgen receptor modulators to enhance their AR binding affinity, AR-mediated transcriptional activation, and in vivo pharmacological activity. The AR binding affinity (Ki) of 29 novel synthetic AR ligands was determined by a radioligand competitive binding assay and ranged from 1.0–51 nm. Compounds with electron-withdrawing substituents at the para- and meta-positions of the B-ring demonstrated the highest AR binding affinity. The AR-mediated transcriptional activation was determined using a cotransfection assay in CV-1 cells. Most compounds with two substituents in the B-ring maintained or improved their functional activity in vitro. However, compounds with three halogen substituents exhibited significant regioselectivity. Fifteen compounds were selected to examine their pharmacological activity in castrated rats. In vivo pharmacological activity and selectivity were significantly changed by structural modification in the B-ring. Compounds with halogen groups at the para- and meta-positions of the B-ring displayed the highest pharmacological activity. Incorporating substituents at the ortho-position of the B-ring resulted in poor pharmacological activity. In vitro and in vivo agonist activities were partially correlated. In conclusion, novel selective androgen receptor modulators with improved in vivo pharmacological activity can be designed and synthesized based on the structure-activity relationship identified in these studies.

The Androgen Receptor (AR) belongs to a super-family of nuclear receptor proteins that are ligand-dependent transcriptional factors. Binding of androgens triggers the conformational change of the AR to its active DNA-binding state, which further interacts with target genes and regulates gene transcription in the presence of appropriate cofactors (1). Androgens act on a number of different target organs by interacting with the AR expressed in those tissues. As such, the AR is a key modulator of processes involved in differentiation, homeostasis, and development of male secondary characters (2). Androgen-related diseases include hypogonadism, male infertility, prostate cancer, delay of puberty, hirsutism, and male pattern baldness.

According to their functional activity or chemical structures, compounds generally are classified as androgens or antiandrogens and steroidal or nonsteroidal ligands, respectively. Androgens are widely used for androgen-deficient diseases, androgen replacement in aging men, and the development of hormonal male contraception. Two naturally occurring steroidal androgens are testosterone and its metabolite, 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). However, the unfavorable physiochemical properties and steroidal-related side effects of these androgens prevent their widespread use in the clinic. Antiandrogens are clinically used to treat androgen-sensitive diseases, including prostate cancer, hirsutism, and androgenic alopecia in women. One class of presently available antiandrogens are steroidal derivatives, such as cyproterone acetate (3) and megestrol acetate (4), which possess mixed agonist and antagonist androgenic activity and cross-react with progesterone receptor. The other class of antiandrogens is nonsteroidal derivatives, such as flutamide, bicalutamide, and nilutamide, which block the AR specifically by competitive binding with the receptor and are widely used for prostate cancer treatment. Considerable efforts are still being made to develop antiandrogens more potent than the first pure antiandrogen (i.e. flutamide), because it is superior to steroidal compounds in terms of AR specificity, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties (5).

Compared with nonsteroidal antiandrogens, the discovery and development of nonsteroidal androgens was delayed for decades. During attempts to affinity label the AR, our laboratory identified the first class of nonsteroidal androgens, which are structural derivatives of flutamide and bicalutamide (6,7). More recently, new nonsteroidal selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) were developed in an attempt to obtain derivatives with higher in vitro activity (8–10), in vivo selective pharmacological activity (11), and better pharmacokinetic properties (12–14). In previous studies, we outlined the key structure-activity relationship of bicalutamide-related androgen agonists to improve AR binding affinity and AR-mediated transcriptional activation (10). These include the importance of an electron-withdrawing group at the para-position of the A-ring, a methyl group linked to the chiral carbon (S-isomer for ether linked compounds and R-isomer for thio-ether linked compounds), an ether or thio-ether linkage, and an electronegative or acetamido group at the para-position of the B-ring. Although the size of the substituent on the B-ring was proved to be limited by both molecular modeling (15) and experiments (9), a novel SARM with a para-chloro group and a meta-fluoro group in the B-ring demonstrated more efficacious and potent pharmacological activity than S-1, one of our known SARMs (16). Furthermore, the addition of electronegative and/or hydrophobic substituents in the B-ring may provide a feasible approach to modulate the hepatic metabolism or endocrine effects of SARMs and identify new drug candidates for other therapeutic applications, including oral, male hormonal contraception. We therefore hypothesized that changing the type, position, and number of substituents in the B-ring would affect the binding affinity, functional activity, and in vivo pharmacological activity of SARMs. The studies reported herein are the first to examine the in vitro and in vivo pharmacological effects of AR ligands with multiple substituents in the B-ring.

We investigated the effects and SARs of such structural modifications on AR binding affinity, AR-mediated transcriptional activation in vitro, and in vivo pharmacological activity. This information reveals how important the B-ring structure is for AR binding and functional activity, information that is valuable for our understanding of the interaction between nonsteroidal androgen ligands and the subpocket within the AR binding site, and that information provides candidates with higher potency and efficacy for possible clinical applications, including treatments of muscle wasting with chronic infections and tumors, osteoporosis, androgen replacement, and hormonal male contraception.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and experimental animals

The S-isomer of synthetic AR ligands (Table 1) was synthesized in our laboratory with a purity greater than 99% using previously described methods (9, 13). [17α-methyl-³H]Mibolerone ([³H]MIB; 84 Ci/mmol) and unlabeled MIB were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Hydroxyapatite (HAP) was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). EcoLite (+) scintillation cocktail was purchased from ICN Research Products Division (Costa Mesa, CA). LipofectAMINE and Passive Lysis Buffer were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

TABLE 1.

AR binding affinity of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-NO2 in the A-ring and two substituents in the B-ring

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | Ki (nm) |

| S-1 | H | H | F | H | H | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| C-1 | F | H | F | H | H | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| C-2 | CH3 | H | F | H | H | 6.0 ± 0.7 |

| C-3 | H | F | F | H | H | 3.4 ± 0.6 |

| C-4 | H | Cl | F | H | H | 10.3 ± 2 |

| C-5 | Cl | H | F | H | H | 5.2 ± 0.9 |

| C-6 | H | F | Cl | H | H | 4.9 ± 0.3 |

| C-7 | H | F | NHC(O)CH3 | H | H | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| C-8 | F | H | Cl | H | H | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| C-9 | Cl | H | Cl | H | H | 9.7 ± 2 |

| C-10 | H | Cl | Cl | H | H | 1.0 ± 0.09 |

| C-11 | H | F | NO2 | H | H | 1.0 ± 0.02 |

| C-12 | F | H | NO2 | H | H | 11 ± 3 |

The Ki value of S-1 was previously reported in Ref. 11. The AR binding affinity (Ki) of each compound was determined using a competitive binding assay as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean ± sd of three experiments.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Bioproducts for Science (Indianapolis, IN). All animals were maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. The animal protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of The Ohio State University.

In vitro AR binding affinity

Rat prostate cytosolic AR was prepared from ventral prostates of castrated male Sprague-Dawley rats using established methods (7). The AR binding affinity of synthetic AR ligands was determined using an in vitro radioligand competitive binding assay as previously described (12). Briefly, an aliquot of AR cytosol was incubated with 1 nm [³H]MIB and 1 mm triamcinolone acetonide at 4 C for 18 h in the absence or presence of 10 increasing concentrations of the compound of interest (10−1 to 104 nm). Nonspecific binding of [³H]MIB was determined by adding excess unlabeled MIB (1000 nm) to the incubate in separate tubes. After incubation, the AR-bound radioactivity was isolated using the HAP method (17). The bound radioactivity was then extracted from HAP and counted. The specific binding of [³H]MIB at each concentration of the compound of interest was calculated by subtracting the nonspecific binding of [³H]MIB and expressed as the percentage of the specific binding in the absence of the compound of interest (B0). The concentration of compound that reduced B0 by 50% (i.e. IC50) was determined using WinNonlin (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA). The equilibrium binding constant (Ki) of the compound of interest was calculated by Ki = Kd × IC50/(Kd + L), where Kd is the dissociation constant of [³H]MIB (0.19 ± 0.01 nm), and L is the concentration of [³H]MIB used in the experiment (1 nm). The Ki value of each compound of interested was further compared.

In vitro AR-mediated transcriptional activation

The in vitro functional activities of nonsteroidal ligands were determined by the ability of each ligand to induce or suppress AR-mediated transcriptional activation, using a modification of the method of Yin et al. (12). On d 1, CV-1 cells at 90% confluence were transiently transfected in T-125 flasks. The transfection was carried out in serum-free DMEM using LipofectAMINE according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cells in each flask were transfected with 0.8 µg of a human AR expression construct (pCMVhAR; generously provided by Dr. Donald Tindall, Mayo Clinic), 4 µg of an androgen-dependent luciferase reporter construct (pMMTV-Luc; generously provided by Dr. Ron Evans, Salk Institute), and 4 µg of a β-galactosidase expression construct (pSV-β- galactosidase; Promega Corp.) for 10 h. Cells were allowed to recover for 12 h and were then seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 8 × 104 cells per well and allowed to recover for an additional 10 h before drug treatment.

The in vitro functional activity of each compound of interest (final concentrations ranging from 1–1000 nm) was determined by incubating cells in the absence (agonist assays) or presence (antagonist assays) of DHT (1 nm). In each experiment, vehicle control and positive control (activity induced by 1 nm DHT) were included. Previous experiments in our laboratories determined that the lowest concentration of DHT that produced maximal AR-mediated transcriptional activation was 1 nm (6). Therefore, in the present study, the transcriptional activation induced by this concentration of DHT was set as 100% and used as the reference for quantifying the agonist activity of each compound. After drug treatment (12 h), cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice and lysed with 110 µl/well of passive lysis buffer for 30 min at room temperature. An aliquot (50 µl) of cell lysate from each well was used for β-galactosidase assays, and the other 50 µl of cell lysate was used for luciferase assays using the method previously described (12). Transcriptional activity in each well was calculated as the ratio of luciferase activity to β-galactosidase activity to avoid variations caused by cell number and transfection efficiency. Transcriptional activity induced by each compound of interest was expressed as the percentage of transcriptional activity induced by 1 nm DHT.

In vivo pharmacological activity

The in vivo pharmacological activity of each synthetic AR ligand was examined in five male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing approximately 200 g. Animals were castrated via a scrotal incision under anesthesia 24 h before drug treatments and received daily sc injections of the compound of interest at a dose rate of 1 mg/d for 14 d. All compounds of interest were freshly dissolved in vehicle containing dimethylsulfoxide (5%, vol/vol) in polyethylene glycol 300 before dose administration. An additional two groups of animals with or without castration received vehicle only and served as castrated or intact control groups, respectively. Animals were killed at the end of the treatment. Plasma samples were collected and stored at −80 C for future use. The ventral prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle were removed, cleared of extraneous tissue, and weighed. All organ weights were normalized to body weight and compared. The weights of prostate and seminal vesicles were used to evaluate androgenic activity, whereas the levator ani muscle weight was used as a measure of anabolic activity.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using single-factor ANOVA with the α-value set a priori at P < 0.05.

Results

Nonsteroidal AR ligand binding affinity

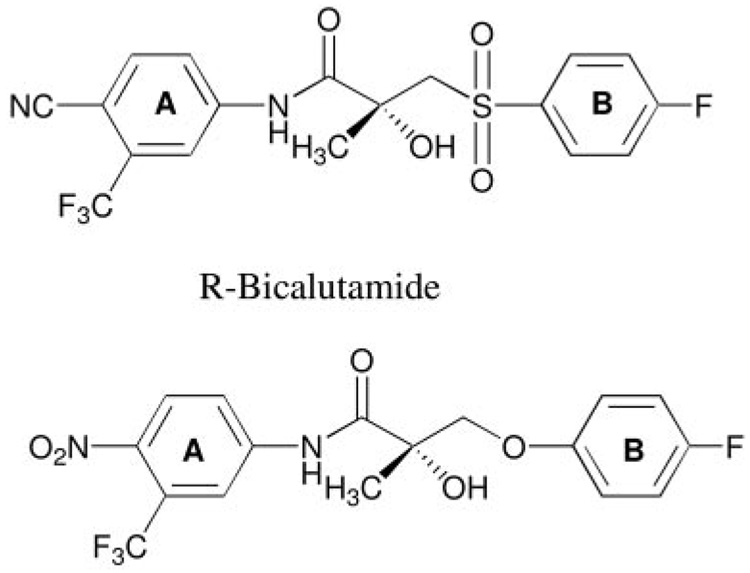

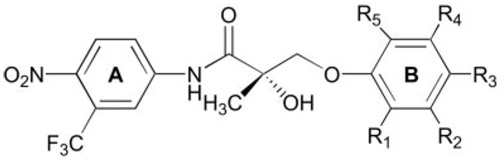

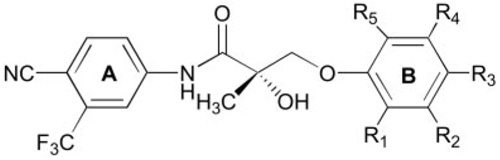

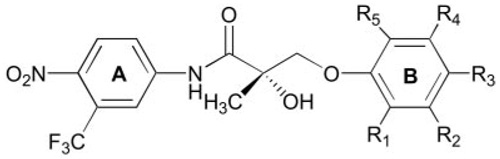

The structure-activity relationships that define the interaction of nonsteroidal compounds with the AR have been studied intensively in our laboratories (6–10, 13) and by several other investigators (18–23). In our search for novel SARMs, a para-fluoro-substituted S-3-(phenoxy)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-propionamides analog known as S-1 (11) was used as our starting point. S-1 was synthesized as a bicalutamide (N-[4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-(4-fluorophenyl)sulfonyl-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-propanamide) derivative and identified as a potent SARM with high in vitro and in vivo activities (24) and potential therapeutic application to benign prostatic hyperplasia (24). As shown in Fig. 1, the key structural elements of S-1 include an electron-deficient aromatic A-ring, a CH3 linked to the chiral carbon (S-isomer), an ether linkage, and electronegative substituents on the aromatic B-ring. Recent crystallographic evidence suggests that the main difference between the AR binding pockets of steroidal androgens (e.g. DHT) and bicalutamide-related SARMs may be the unique interactions of the B-ring with additional amino acids near tryptophan 741 (25). A series of nonsteroidal compounds with multiple substitutions on the B-ring were designed and synthesized to study the effects of structural modification on AR binding affinity and functional activity. The AR binding affinity of synthetic compounds was determined using an in vitro radioligand competitive binding assay and are reported here as the inhibition constant (Ki) in Table 1–Table 3. Synthetic compounds showed a wide range of binding affinity with Ki values ranging from 1.0–51 nm, which provide an index of the relative binding affinities of compounds of interest. The binding affinity (Ki value) for R-bicalutamide was previously determined as 11.0 nm using identical methods (26).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of R-bicalutamide and S-1.

TABLE 3.

AR binding affinity of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-CN in the A-ring and multiple substituents in the B-ring

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | Ki(nm) |

| S-1 | H | H | F | H | H | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| C-25 | F | H | F | H | H | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| C-26 | H | F | F | H | H | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| C-27 | Cl | H | Cl | H | H | 20 ± 0.2 |

| C-28 | H | Cl | Cl | H | H | 5.0 ± 0.2 |

| C-29 | F | F | F | F | F | 6.8 ± 0.4 |

The Ki value of S-1 was previously reported in Ref. 11. The AR binding affinity (Ki) of each compound of interested was determined using a competitive binding assay as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean ± sd of three experiments.

Table 1 shows the Ki values of compounds with a para-nitro group in the A-ring and two substituents in the B-ring. Previous studies from our laboratories confirmed that with a single substituent in the B-ring, para-substitution was superior to meta-substitution in terms of AR binding (8, 10). Compared with the lead compound, S-1, the incorporation of an additional fluoro, chloro, or methyl group at the ortho-position (i.e. R1 of the general structure shown in Table 1) of the B-ring increased or maintained AR-binding affinity, suggesting that an electron-deficient B-ring is more favorable. We also examined the influence of an additional meta-fluoro substituent (i.e. R2) on AR binding affinity of a series of compounds with varying para-substituents. The order of AR binding affinity was NO2 > F > Cl > NHC(O)CH3 (C-11 > C-3 > C-6 > C-7), corroborating crystallographic evidence with bicalutamide that hydrogen bonding with para-substituent of SARMs is likely important for high-affinity binding. AR binding affinity was optimal when there were two electron-withdrawing groups present in the meta- and para-positions of the aromatic B-ring. This is exemplified by the low Ki values (~1.0 nm) of C-10 and C-11. For these two compounds, moving the chloro group or fluoro group from the meta-position (C-10 and C-11) to the ortho-position (C-9 and C-12) resulted in a 10-fold decrease in AR binding affinity. However, this regioselectivity was not true for other pairs of compounds C-1/C-3, C-4/C-5, and C-6/C-8, indicating that this selectivity may be substituent dependent.

Having demonstrated that AR binding affinity improved by incorporation of additional electron-withdrawing groups in the aromatic B-ring, we applied more halogen groups to the B-ring to further explore the effects of substitution positions and types on AR binding affinity. Compounds with three or five substituents in the B-ring were designed and synthesized. As shown in Table 2, when three fluoro groups were incorporated in the different positions of the B-ring, high AR binding affinity was maintained in each case. In particular, C-18, which bears fluoro groups at the 2-, 4-, and 5-positions of the B-ring, had significantly improved AR binding affinity with a Ki value as low as 1.0 nm. These three positions of the B-ring were also the best combination for chloro-substituted compounds (C-19 to C-22) in terms of binding affinity. However, in general, changing a fluoro group to a chloro group (C-13/C-19, C-14/C-20, C-17/C-21, and C-18/C-22) significantly decreased AR binding affinity, indicating that the size of substituents is critical when the B-ring has more than two substituents. To protect the aromatic B-ring from possible oxidation in vivo, all positions of the B-ring were occupied by introducing five halogen groups (C-23 and C-24). The excellent AR binding affinity of C-23 suggested that as many as five fluoro groups are well tolerated in the B-ring. Again, replacing the fluoro group of C-23 with a chloro group increased the Ki value but still maintained a reasonable AR binding affinity in vitro.

TABLE 2.

AR binding affinity of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-NO2 in the A-ring and three or five substituents in the B-ring

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | Ki(nm) |

| S-1 | H | H | F | H | H | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| C-13 | F | F | F | H | H | 11 ± 1 |

| C-14 | F | F | H | F | H | 9.1 ± 0.6 |

| C-15 | F | F | H | H | F | 7.5 ± 1 |

| C-16 | H | F | F | F | H | 4.0 ± 0.9 |

| C-17 | F | H | F | H | F | 5.9 ± 0.6 |

| C-18 | F | H | F | F | H | 0.97 ± 0.1 |

| C-19 | Cl | Cl | Cl | H | H | 50 ± 5 |

| C-20 | Cl | Cl | H | Cl | H | 27 ± 2 |

| C-21 | Cl | H | Cl | H | Cl | 51 ± 5 |

| C-22 | Cl | H | Cl | Cl | H | 10 ± 2 |

| C-23 | F | F | F | F | F | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| C-24 | F | F | Cl | F | F | 11 ± 0.8 |

The Ki value of S-1 was previously reported in Ref. 11. The AR binding affinity (Ki) of each compound was determined using a competitive binding assay as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean ± sd of three experiments.

In previous studies, AR binding affinity was significantly improved by replacing the para-cyano group with a nitro group in the aromatic A-ring of hydroxyflutamide analogs (6), but it was not true in bicalutamide derivatives (9). To investigate the effects of such a change on the AR binding affinity of compounds with multiple substituents in the B-ring, some compounds listed in Table 1 and Table 2 were structurally modified as shown in Table 3. For compounds with two fluoro groups in the B-ring (C-25 and C-16), binding affinities were similar between analogs bearing a nitro group or a cyano group at the para-position of the A-ring (compare C-25 vs. C-1 and C-26 vs. C-3). In all other cases, the cyano-substituted compounds exhibited at least a 2-fold lower AR binding affinity than their corresponding nitro-substituted counterparts (pairs C-27/C-9, C-28/C-10, and C-29/C-23).

In vitro functional activity of nonsteroidal AR ligands

Transcriptional activation induced by DHT plateaued at a concentration of 1 nm, as reported previously (6), and was used as a positive control (i.e. 100%) in each experiment to facilitate comparison with previous studies (10). Agonist activity and antagonist activity were determined in the absence or presence of 1 nm DHT, respectively. Ligands were defined as full AR agonists if compounds induced a similar level of transcriptional activation as that of 1 nm DHT in the agonist assay; ligands were defined as partial agonists if compounds induced a certain level (≥10%) of transcriptional activation but still significantly lower than that of 1 nm DHT in the agonist assay; ligands were defined as antagonists if compounds induced a low level (<10%) of transcriptional activation in the agonist assay and a significantly decreased level of transcriptional activation induced by 1 nm DHT in the antagonist assay (10).

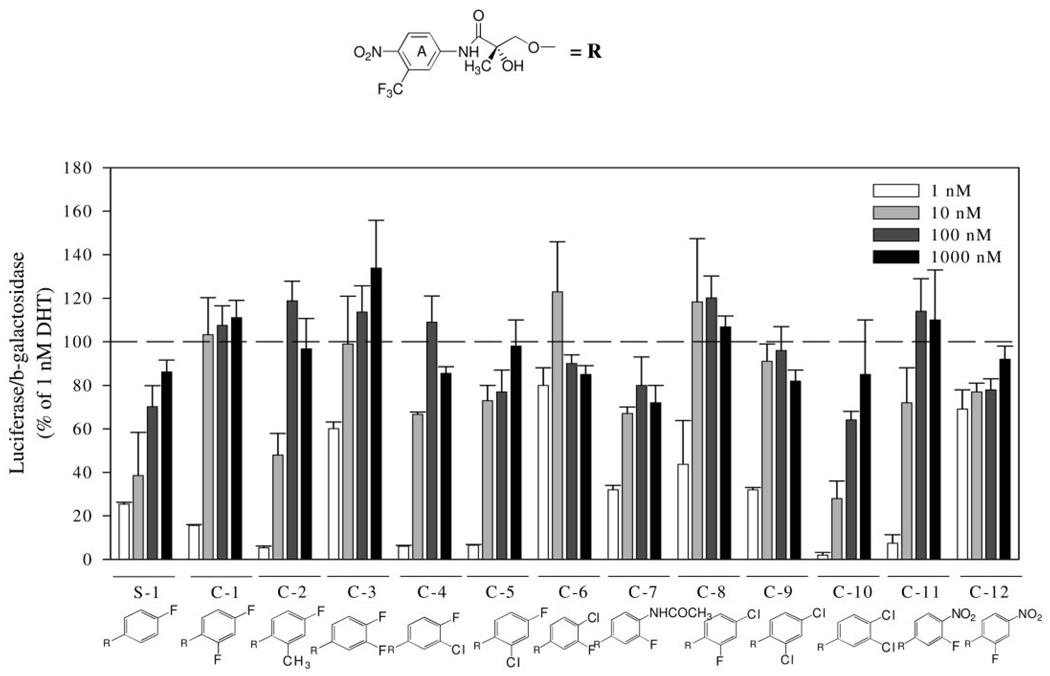

Figure 2 shows the AR agonist activity of ligands with a para-nitro group in the A-ring and two substituents in the B-ring. All compounds examined in this series induced transcriptional activation in a concentration-dependent manner. In the presence of 1 nm DHT, no significant antagonist activity (data not shown) was observed for this series of compounds at concentrations up to 1 µm, suggesting that the introduction of two substituents does not interfere with the formation of the transcriptional active ligand binding domain (LBD) conformation. Except for C-12, the incorporation of two substituents in the aromatic B-ring maintained or improved the AR-mediated transcriptional activation compared with previous studies (10). Compounds C-1 through C-11 therefore were identified as full agonists, whereas C-12 was identified as a partial agonist. Among this series of compounds, C-11 was one of the ligands with the highest AR binding affinity (Ki = 1.0 ± 0.02 nm) and exhibited the most potent agonist activity. It is noteworthy that at a concentration of 10 nm, compounds with high binding affinity (e.g. Ki < 5) are as efficient as 1 nm DHT. Additional consistency between AR binding affinity and transcriptional activation is that the meta- and para-positions of the B-ring are the optimal substituent positions for both binding and functional activities as exemplified by C-3, C-6, and C-11. However, inconsistency was also observed. For instance, C-10 (Ki ~1 nm) displayed less potent agonist activity than C-3 and C-6, which demonstrated 4- to 5-fold lower binding affinity than C-10. Also interestingly, moving the fluoro group of C-11 from its meta-position to the ortho-position (C-12) of the B-ring caused a 10-fold increase of the Ki value but a more than 1000-fold decrease of the AR-mediated transcriptional activation. Although the presence of a fluoro group at the ortho-position of the B-ring was well tolerated in terms of binding with the AR, it appears to prevent the formation of transcriptionally active AR.

FIG. 2.

AR-mediated transcriptional activation of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-NO2 in the A-ring and two substituents in the B-ring. CV-1 cells were transfected with a human AR plasmid, an androgen-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid, and a constitutively expressed β-galactosidase plasmid in a T-175 flask using LipofectAMINE. After transfection, cells were plated onto 24-well plates and allowed to recover for 12 h before drug treatment. Cells were then treated with vehicle, 1 nm DHT, or increasing concentrations of the AR ligand of interest for 24 h. Luciferase activity in each well was normalized with the β-galactosidase activity and then expressed as the percentage of that induced by 1 nm DHT. Each bar represents mean ± sd (n = 3).

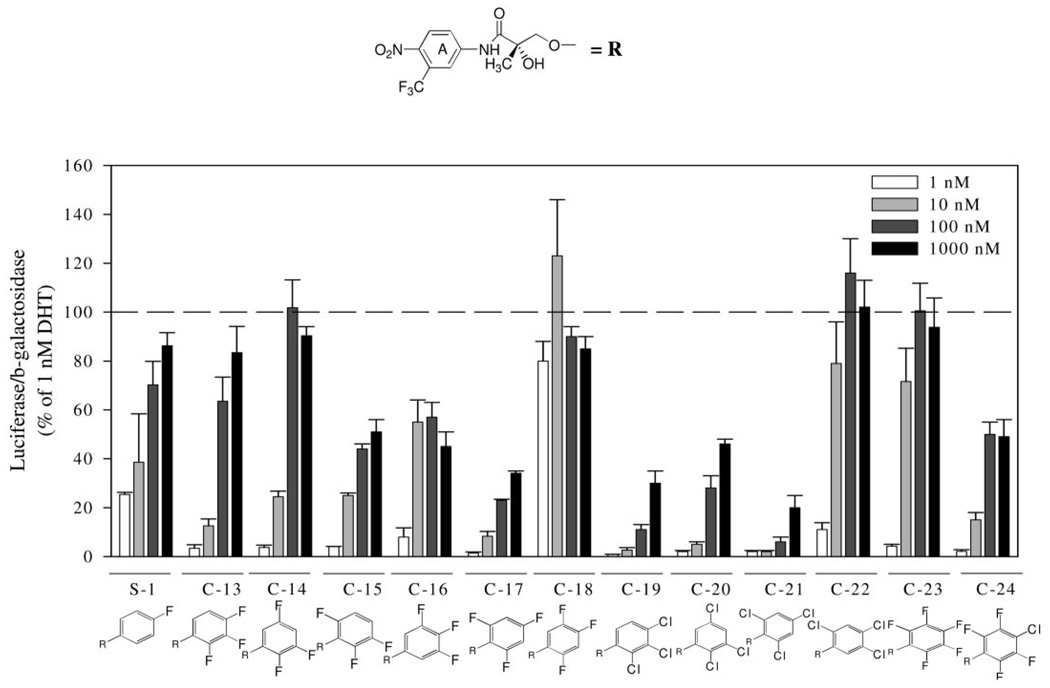

C-13 through C-24 are AR ligands with a para-nitro group in the A-ring and three or five substituents in the B-ring. AR-mediated transcriptional activity induced by these compounds is shown in Fig. 3. Five compounds were identified as full agonists (C-13, C-14, C-18, C-22, and C-23), whereas the other seven compounds were identified as partial agonists. In antagonist assays, full agonists exhibited no significant effect on transcriptional activation induced by 1 nm DHT, whereas partial agonists demonstrated a concentration-dependent inhibition with about a 60% decrease for the most potent ligand (i.e. C-17) (data not shown). Obviously, for compounds with three substituents in the B-ring, the substituent type, number, and/or positions are critical in terms of both binding affinity and functional activity. C-18 and C-22 not only showed the best binding affinity but also induced the most potent and efficacious transcriptional activation among trifluoro- and trichloro-substituted compounds, respectively. It is important to note that the transcriptional activation induced by 1 nm C-18 was comparable to that observed with 1 nm DHT, although C-18 (Ki ~1 nm) demonstrated a 2- to 3-fold lower binding affinity than DHT (Ki ~0.4 nm). As the B-ring became bulkier because of incorporation of more substituents, we observed significant regioselectivity. Pairs of compounds (C-14/C-15, C-18/C-17, and C-22/C-21) were designed so that only a single substituent position was different in the B-ring between these two ligands. Moving the fluoro/chloro group from position 5 to position 6 (i.e. from R4 to R5 in the structure of Table 2) of the B-ring significantly decreased the transcriptional activation, indicating that the presence of two electron-withdrawing groups at both ortho-positions of the B-ring deteriorated the functional activity. For compounds C-19 to C-21, the low transcriptional activation was most likely a result of their low binding affinity. However, despite the higher binding affinity of compounds C-15 to C-17, functional activity induced by these compounds was lower than that of C-13 and C-14. Again, both binding affinity and the potential to form a transcriptionally active AR of a ligand are important to determine its functional activity. The incorporation of five fluoro groups in the B-ring was well tolerated for both binding affinity and functional activity. Changing the para-fluoro group of C-23 to a chloro group (C-24) significantly decreased its agonist activity.

FIG. 3.

AR-mediated transcriptional activation of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-NO2 in the A-ring and three or five substituents in the B-ring. CV-1 cells were transfected with a human AR plasmid, an androgen-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid, and a constitutively expressed β-galactosidase plasmid in a T-175 flask using LipofectAMINE. After transfection, cells were plated onto 24-well plates and allowed to recover for 12 h before drug treatment. Cells were then treated with vehicle, 1 nm DHT, or increasing concentrations of the AR ligand of interest for 24 h. Luciferase activity in each well was normalized with the β-galactosidase activity and then expressed as the percentage of that induced by 1 nm DHT. Each bar represents mean ± sd (n = 3).

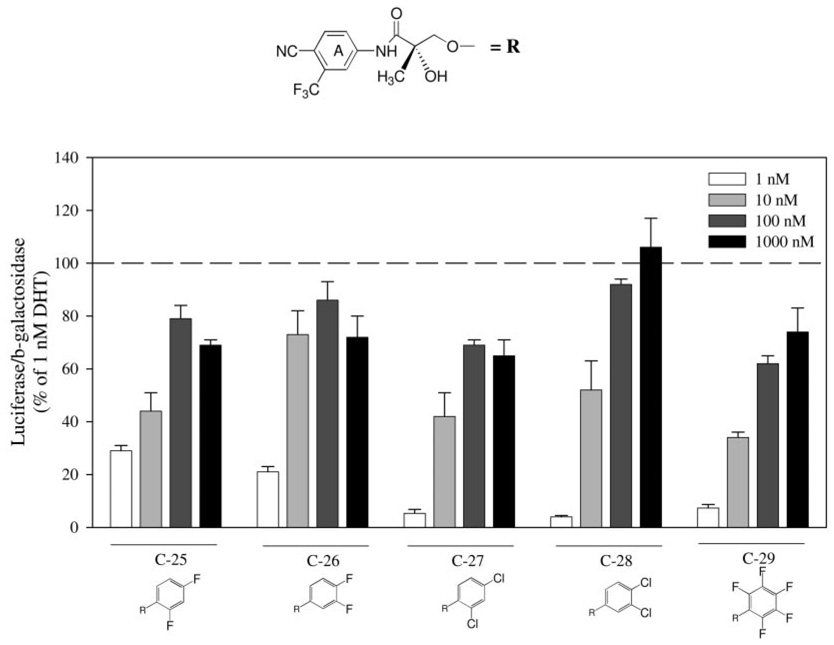

In binding studies, all five ligands with a para-CN group in the A-ring demonstrated similar or lower binding affinity than their counterparts with a para-NO2 group. In agonist assays (Fig. 4) all five cyano-substituted compounds exhibited reasonably high agonist activity and were identified as full agonists, because no significant inhibition of activity induced by DHT was observed (data not shown). Comparing compounds with nitro- and cyano-substituents in the A-ring, it was obvious that the presence of the A-ring cyano group led to a slightly decreased functional activity in all cases, which correlated well with the binding affinity.

FIG. 4.

AR-mediated transcriptional activation of nonsteroidal AR ligands with a para-CN in the A-ring and multiple substituents in the B-ring. CV-1 cells were transfected with a human AR plasmid, an androgen-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid, and a constitutively expressed β-galactosidase plasmid in a T-175 flask using LipofectAMINE. After transfection, cells were plated onto 24-well plates and allowed to recover for 12 h before drug treatment. Cells were then treated with vehicle, 1 nm DHT, or increasing concentrations of the AR ligand of interest for 24 h. Luciferase activity in each well was normalized with the β-galactosidase activity and then expressed as the percentage of that induced by 1 nm DHT. Each bar represents mean ± sd (n = 3).

In vivo pharmacological activity of nonsteroidal AR ligands

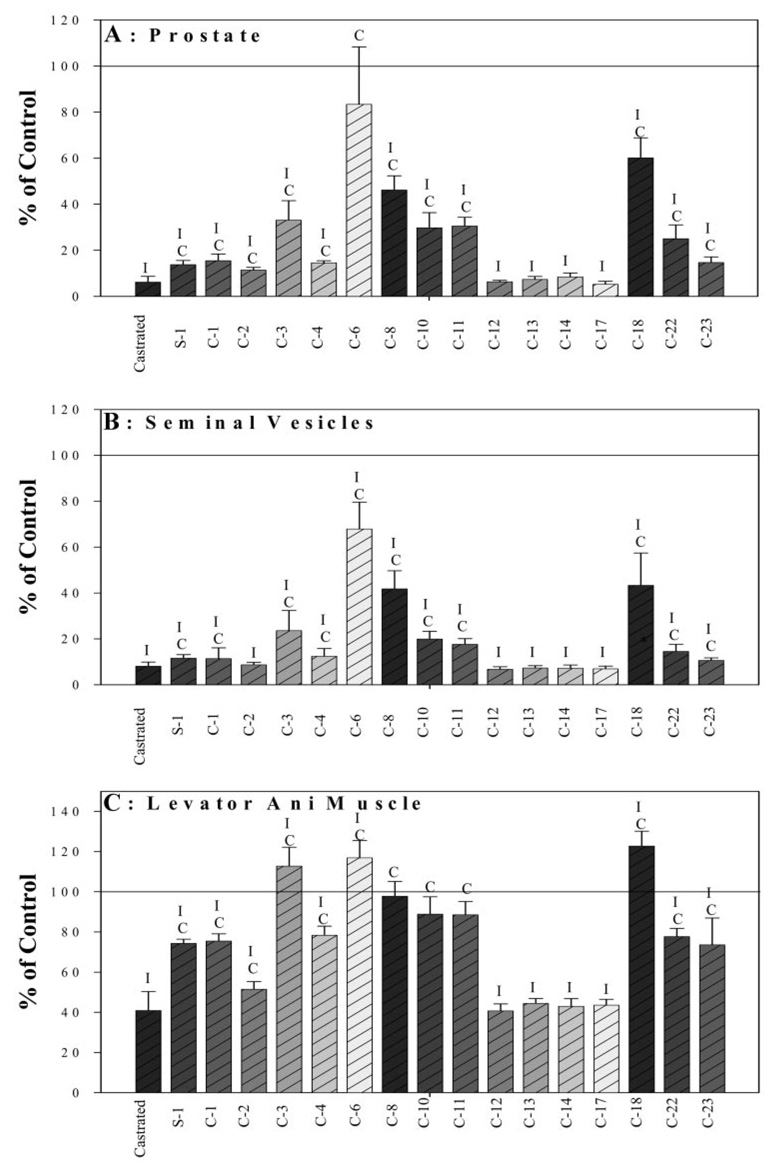

The studies above demonstrate that certain structural modifications in the B-ring of nonsteroidal AR ligands improve AR binding affinity and functional activity in vitro. However, high binding affinity and agonist activity do not always predict high pharmacological activity, as shown by Yin et al. (12). Previous studies in our laboratories showed that exogenous administration of testosterone to castrated male rats increased the weights of androgenic and anabolic organs in a dose-dependent manner and achieved maximal effects at a dose of 0.75 mg/d. The potency and efficacy of testosterone propionate (TP) on the prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle of castrated rats were approximately equal. For example, the weights of the prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle were maximally restored by TP to 121, 70, and 104% of intact control, respectively (11). A dose of 1 mg/d of TP could not be evaluated because of poor solubility. In contrast, S-1 maximally restored the weights of the prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle to 15, 13, and 74% of intact control, respectively, demonstrating the higher in vivo anabolic activity than androgenic activity of S-1 and identifying it as a SARM. In the present studies, a single high dose (1 mg/d for 14 d) was used to examine the pharmacological effects of selected ligands on the prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle in castrated male rats. Because replacing a para-nitro with a cyano group in the A-ring decreased the binding affinity and transcriptional activity of these compounds in most cases, compounds selected for in vivo studies all bear a para-nitro group in the A-ring. Figure 5 shows the androgenic activity (panel A, prostate; panel B, seminal vesicles) and anabolic activity (panel C, levator ani muscle) of AR ligands of interest. Because of the depletion of endogenous testosterone, castration led to a rapid reduction of the weight in prostate, seminal vesicles, and levator ani muscle to 6.2, 8.1, and 41% of intact levels, respectively. According to the potency and efficacy of AR agonists, the weights of androgen-dependent organs would remain low, partially, or fully maintained after drug treatment.

FIG. 5.

Pharmacological activity of novel AR ligands in castrated male rats. Castrated male rats received each AR ligand at a dose of 1 mg/d by daily sc injection for 14 d. Organ weights were normalized with body weight and expressed as the percentage of the weights in the intact control group. Each bar represents the mean ± sd (n = 5 per group). Letters I and C above each error bar represent a significant difference between the group and intact or castrated control group, respectively, as analyzed by single-factor ANOVA with P < 0.05.

For compounds with two substituents in the B-ring, the position and size of substituents clearly played an important role in the in vivo pharmacological activity. Introduction of an additional fluoro group at the ortho-position (C-1) resulted in equipotent pharmacological activity to S-1, suggesting that a small electron-withdrawing group at this position is well tolerated. However, changing this ortho-fluoro group to an ortho-methyl group (C-2) significantly decreased its anabolic activity (Fig. 5C), consistent with the structure-activity relationship from the AR binding studies. Interestingly, when the ortho-fluoro group was moved to the meta-position of the B-ring (C-3), the compound demonstrated much higher pharmacological activity than C-1, largely because of the improved transcriptional activation instead of AR binding affinity. The ortho/meta-regioselectivity was further illustrated by the potencies of C-6 and C-11 compared with those of C-8 and C-12. When the meta-fluoro group of C-3 was replaced by a chloro group (C-4), significantly decreased pharmacological activity was observed, indicating that the size of the meta-substituent is critical. Besides S-1, Yin et al. (11) identified another more potent SARM (S-4) that bears a relatively larger substituent (acetamido group) at the para-position of the B-ring. Therefore, larger substituents were also incorporated into that position to discover new structure-activity relationships in the current study. Replacing the para-fluoro group with a chloro group resulted in a 3-fold increase in androgenic activity (pairs C-1/C-8 and C-3/C-6) and 30% increase in anabolic activity (pair C-1/C-8). As we previously reported (11, 16), the maximum effect of our SARMs in levator ani muscle plateaued at about 120–140% of the intact control level. Therefore, the greatly improved pharmacological effects of C-6 over C-3 were observed only in the prostate and seminal vesicles but not in the muscle. Although at a dose rate of 1 mg/d, C-6 demonstrated both high androgenic and anabolic activity, a complete dose-response study showed that C-6 retains tissue selectivity over the physiological dose range (16). Surprisingly, replacing the para-fluoro group of C-3 with a nitro group (C-11) decreased the pharmacological effect, despite the fact that the AR binding affinity of C-11 was 3-fold higher than that of C-3 in vitro. The relatively low in vivo activity of C-11 was likely a result of its rapid in vivo metabolism because both nitro groups on the A-ring and B-ring are susceptible to reduction to an amine group (Chen, J., K. Chung, D. D. Miller, and J. T. Dalton, manuscript in preparation).

Compounds C-12, C-13, C-14, and C-17, which were identified as partial agonists in vitro, failed to show any activity in vivo. Besides the low functional activity identified in vitro, rapid metabolism could have also played a role in their inactivity in vivo. Consistent with results of in vitro studies, the 2-, 4-, and 5-position in the B-ring are the optimal locations to incorporate three electron-withdrawing substituents. Among compounds with three substituents in the B-ring, only C-18 and C-22 exhibited high activity in vivo. C-18 demonstrated significantly higher androgenic and anabolic activity than S-1, whereas C-22 showed similar pharmacological activity as S-1. Obviously, changing the type and position of substituents in the B-ring altered the androgenic activity/anabolic activity ratio in rats. Although the incorporation of five fluoro groups in the B-ring significantly improved the AR binding affinity and transcriptional activation in vitro, the in vivo pharmacological activity was similar as that of S-1. Results from pharmacokinetic and metabolism studies of C-23 showed that the ether linkage is vulnerable in vivo when it is coupled with a five fluoro-substituted B-ring. In conclusion, the incorporation of multiple electron-withdrawing substituents in the B-ring is a novel method to improve pharmacological activity.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that novel AR agonists with a wide range of in vitro and in vivo activities can be designed by structural modifications of the SARM pharmacophore. Early structure-activity relationship work on hydroxyflutamide analogs (27) confirmed the importance of an electron-deficient aromatic A-ring and the substituents attached to the carbon atom bearing a tertiary hydroxy group. Two years later, Tucker et al. (18) reported that the AR binding and antiandrogen activity of hydroxyflutamide and bicalutamide derivatives were optimum when the 4-substituent in the A-ring was either a cyano or nitro group and the 3-substituent was a chloro or trifluoromethyl group. Interestingly, partial androgen agonist activity was observed in some trifluoromethyl-substituted compounds, indicating that AR agonists can be designed and developed by subtle structural modification(s) of known AR antagonists. When this concept was applied to discover novel bicalutamide-related AR agonists in our laboratories, important in vitro SARs for the AR binding affinity and agonist activity were further gained (10), including a para-nitro group in the A-ring, a trifluoromethyl group linked to the chiral carbon (R-isomer), a sulfide linkage, and a para-N-alkylamido group in the B-ring. However, when these compounds were tested in vivo, no pharmacological activity was observed because of their unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties (12). Additional structural modification was made to overcome this problem by changing the sulfide linkage to an ether bridge, which resulted in the successful discovery of SARMs (11). As shown in Fig. 1, the lead compound of current studies (S-1) contains a para-nitro group and a meta-trifluoromethyl group in the A-ring, a methyl group linked to the chiral carbon (S-isomer), an ether linkage, and a para-fluoro substituent in the B-ring. Because of the difficult chemical synthesis and the small advantage of a trifluoromethyl group over a methyl group in terms of the AR binding affinity, a methyl group was linked to the chiral carbon. Results from our binding studies showed that the incorporation of multiple substituents in the B-ring was well tolerated. Four compounds with multiple electron-withdrawing substituents in the B-ring (C-10, C-11, C-18, and C-23) exhibited high AR binding affinity (Ki ~ 1.0 nm), which was even slightly higher than that of the endogenous androgen testosterone. The significantly improved AR binding affinity was most likely either a result of increased hydrophobic interactions (C-10, C-18, and C-23) between halogen groups with the B-ring subpocket or the formation of hydrogen bonds formed between the para-nitro group (C-11) and the AR binding site. Crystallographic studies are underway in our laboratory to define the precise mechanism(s). Several structural modifications increased AR binding affinity, indicating that there is a free space surrounding the B-ring within the AR binding pocket, which is flexible to accommodate ligands with a different B-ring. The interaction between the AR and bicalutamide-related compounds with multiple substituents in the B-ring is favorable if 1) two electron-withdrawing groups are at the para- and meta-positions of the B-ring, 2) a H-bond acceptor is present at the para-position of the B-ring, 3) three substituents are at the 2-, 4-, and 5-positions of the B-ring, and 4) fluoro groups instead of chloro groups are incorporated in the B-ring for compounds with more than two substituents in that ring.

Structural studies on the LBD of the AR revealed an α-helical sandwich fold consisting of 12 α-helices (H1–H12) and a short β-sheet (28, 29), which was consistent with the canonical structure of the other nuclear hormone receptor LBDs (28–32). Comparison of the LBD structures of nuclear receptor in complex with an agonist and an antagonist suggested that receptor ligands trigger different conformation changes, especially the position of helix H12 and the unwinding of helix H11 (30, 33). Upon binding with an agonist, helix H12 folds back, seals the ligand binding pocket (LBP) as a lid, and forms a surface to interact with coactivators. On the other hand, binding with an antagonist is thought to induce unwinding of helix H11 and allow helix H12 to disrupt the overall surface topography of AF-2 and/or the recruitment of coactivators (34). By incorporation of multiple substituents in the B-ring of our known SARM, novel AR agonists with higher binding affinity and pharmacological activity were discovered, suggesting that the LBP around the B-ring area is flexible and that substituents with smaller atomic sizes can be well tolerated to stabilize a transcriptionally active LBP conformation via creation of new hydrophobic interactions or hydrogen bond (6). It is noteworthy that significant regioselectivity was observed for compounds with three substituents in the B-ring. Functional activity changed between agonist and partial agonist by moving the fluoro/chloro groups along the aromatic ring and was optimized at the 2-, 4-, and 5-positions of the B-ring (C-18 and C-22). Because high AR binding affinity was maintained by incorporation of three fluoro groups in the B-ring (C-13 to C-18), functional results suggested that this regioselectivity may be related to the precise position of helix H12, strongly stabilized by pure agonist (C-18) or destabilized by partial agonist (C-15 to C-17). It is possible that an intermediate position of helix H12 exists for these partial agonists. Additional site-directed mutagenesis data with the AR suggests that the interaction between Thr (877) of the AR and non-steroidal ligands is important to determine the functional activity of this series of AR ligands. For example, the partial agonist, C-17, behaved as a potent and pure agonist in CV-1 cells cotransfected with mutant AR (T877A) and reporter plasmids (forthcoming report). To date, crystal structures are available only for the wild-type AR-LBD complex with steroidal AR ligands (28, 29) but not with any nonsteroidal AR ligands. Chemical structures reported herein make it possible to study the detailed interactions between the aromatic B-ring and AR-LBP, especially within the unique subpocket of nonsteroidal compounds. Ongoing studies focused on this subject include molecular modeling, site-directed mutagenesis, and x-ray crystallography to define the precise molecular mechanisms underlying SARM interactions with the AR and functional activity.

The in vivo pharmacological activity of SARMs is determined by several ligand characteristics, including AR binding affinity, ability to stimulate AR function (i.e. transcriptional activation), and metabolic stability. Previous studies in our laboratories demonstrated that the different pharmacological activity of some SARMs with a single para-halogen substituent was solely a result of differences in systemic exposure rather than intrinsic activity (35). Despite less in vivo drug exposure, C-3 demonstrated higher pharmacological activity than S-1 (forthcoming report), indicating a change in intrinsic pharmacological activity after structural modification. Among the SARMs with multiple substituents in the B-ring, their maximal effects on androgenic and anabolic tissues can be dramatically altered by incorporation of different halogens at the para-position of the B-ring (e.g. C-6) (16). In addition, the effects of these compounds on hormonal regulation, including LH, FSH, and testosterone may also be changed by structural modifications. Ongoing studies in our laboratories include those to examine the in vitro functional activity, pharmacokinetics and dose-response relationships of active compounds, and in vivo pharmacological effects on muscle, bone, spermatogenesis, and hormonal regulation.

In summary, the current studies revealed the in vitro and in vivo structure-activity relationships of AR ligands, proved that structural modification in the B-ring of our known SARMs is a feasible method to discover and develop novel SARMs with higher pharmacological activity and better selectivity, made it feasible to further design and discover new SARMs, and provided candidates for androgen-related therapy, including muscle-wasting diseases, osteoporosis, benign prostate hyperplasia, hormonal male contraception, and androgen replacement.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grants from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1 R01 DK59800-05) and GTx, Inc. (Memphis, TN). J.C. was partially supported by a Presidential Fellowship from the Ohio State University.

Abbreviations

- AR

Androgen receptor

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- HAP

hydroxyapatite

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- LBP

ligand binding pocket

- MIB

mibolerone

- SARM

selective androgen receptor modulator

References

- 1.Zhou ZX, Wong CI, Sar M, Wilson EM. The androgen receptor: an overview. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1994;49:249–274. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571149-4.50017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto AM. Hormonal therapy of male hypogonadism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23:857–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowszowicz I. Antiandrogens. Mechanisms and paradoxical effects. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1989;50:189–199. (French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLeod DG. Antiandrogenic drugs. Cancer. 1993;71:1046–1049. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1046::aid-cncr2820711424>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaillard-Moguilewsky M. Pharmacology of antiandrogens and value of combining androgen suppression with antiandrogen therapy. Urology. 1991;37:5–12. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(91)80095-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalton JT, Mukherjee A, Zhu Z, Kirkovsky L, Miller DD. Discovery of nonsteroidal androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:1–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukherjee A, Kirkovsky LI, Kimura Y, Marvel MM, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Affinity labeling of the androgen receptor with nonsteroidal chemoaffinity ligands. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkovsky L, Mukherjee A, Yin D, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Chiral nonsteroidal affinity ligands for the androgen receptor. 1. Bicalutamide analogues bearing electrophilic groups in the B aromatic ring. J Med Chem. 2000;43:581–590. doi: 10.1021/jm990027x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Yin D, Perera M, Kirkovsky L, Stourman N, Li W, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Novel nonsteroidal ligands with high binding affinity and potent functional activity for the androgen receptor. Eur J Med Chem. 2002;37:619–634. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(02)01335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin D, He Y, Perera MA, Hong SS, Marhefka C, Stourman N, Kirkovsky L, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Key structural features of nonsteroidal ligands for binding and activation of the androgen receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:211–223. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin D, Gao W, Kearbey JD, Xu H, Chung K, He Y, Marhefka CA, Veverka KA, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Pharmacodynamics of selective androgen receptor modulators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1334–1340. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin D, Xu H, He Y, Kirkovsky LI, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism of acetothiolutamide, a novel nonsteroidal agonist for the androgen receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1323–1333. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marhefka CA, Gao W, Chung K, Kim J, He Y, Yin D, Bohl C, Dalton JT, Miller DD. Design, synthesis, and biological characterization of metabolically stable selective androgen receptor modulators. J Med Chem. 2004;47:993–998. doi: 10.1021/jm030336u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kearbey JD, Wu D, Gao W, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Pharmacokinetics of S-3-(4-acetylamino-phenoxy)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-propionamide in rats, a non-steroidal selective androgen receptor modulator. Xenobiotica. 2004;34:273–280. doi: 10.1080/0049825041008962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohl CE, Chang C, Mohler ML, Chen J, Miller DD, Swaan PW, Dalton JT. A ligand-based approach to identify quantitative structure-activity relationships for the androgen receptor. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3765–3776. doi: 10.1021/JM0499007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Hwang DJ, Bohl CE, Miller DD, Dalton JT. A selective androgen receptor modulator for hormonal male contraception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:546–553. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hechter O, Mechaber D, Zwick A, Campfield LA, Eychenne B, Baulieu EE, Robel P. Optimal radioligand exchange conditions for measurement of occupied androgen receptor sites in rat ventral prostate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:49–68. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tucker H, Crook JW, Chesterson GJ. Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 3-substituted derivatives of 2-hydroxypropionanilides. J Med Chem. 1988;31:954–959. doi: 10.1021/jm00400a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JJ, Hughes LR, Glen AT, Taylor PJ. Non-steroidal antiandrogens: design of novel compounds based on an infrared study of the dominant conformation and hydrogen-bonding properties of a series of anilide antiandrogens. J Med Chem. 1991;34:447–455. doi: 10.1021/jm00105a067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teutsch G, Goubet F, Battmann T, Bonfils A, Bouchoux F, Cerede E, Gofflo D, Gaillard-Kelly M, Philibert D. Non-steroidal antiandrogens: synthesis and biological profile of high-affinity ligands for the androgen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;48:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakeling AE, Furr BJ, Glen AT, Hughes LR. Receptor binding and biological activity of steroidal and nonsteroidal antiandrogens. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;15:355–359. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishioka T, Kubo A, Koiso Y, Nagasawa K, Itai A, Hashimoto Y. Novel non-steroidal/non-anilide type androgen antagonists with an isoxazolone moiety. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamann LG, Higuchi RI, Zhi L, Edwards JP, Wang XN, Marschke KB, Kong JW, Farmer LJ, Jones TK. Synthesis and biological activity of a novel series of nonsteroidal, peripherally selective androgen receptor antagonists derived from 1,2-dihydropyridono[5,6-g]quinolines. J Med Chem. 1988;41:623–639. doi: 10.1021/jm970699s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao W, Kearbey JD, Nair VA, Chung K, Parlow AF, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Comparison of the pharmacological effects of a novel selective androgen receptor modulator, the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride, and the antiandrogen hydroxyflutamide in intact rats: new approach for benign prostate hyperplasia. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5420–5428. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohl CE, Gao W, Miller DD, Bell CE, Dalton JT. Structural basis for antagonism and resistance of bicalutamide in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6201–6206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500381102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee A, Kirkovsky L, Yao XT, Yates RC, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Enantioselective binding of Casodex to the androgen receptor. Xenobiotica. 1996;26:117–122. doi: 10.3109/00498259609046693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glen AT, Hughes LR, Morris JJ, Taylor PJ. Structure-activity relationships among nonsteroidal antiandrogens. In: Lambert RW, editor. Proceedings of the Third Sci-RSC Medicinal Chemistry Symposium. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 1986. pp. 345–361. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matias PM, Donner P, Coelho R, Thomaz M, Peixoto C, Macedo S, Otto N, Joschko S, Scholz P, Wegg A, Basler S, Schafer M, Egner U, Carrondo MA. Structural evidence for ligand specificity in the binding domain of the human androgen receptor: implications for pathogenic gene mutations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26164–26171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sack JS, Kish KF, Wang C, Attar RM, Kiefer SE, An Y, Wu GY, Scheffler JE, Salvati ME, Krystek SR, Jr, Weinmann R, Einspahr HM. Crystallographic structures of the ligand-binding domains of the androgen receptor and its T877A mutant complexed with the natural agonist dihydrotestosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4904–4909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081565498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourguet W, Ruff M, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding domain of the human nuclear receptor RXR-α. Nature. 1995;375:377–382. doi: 10.1038/375377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renaud JP, Rochel N, Ruff M, Vivat V, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. Crystal structure of the RAR-γ ligand-binding domain bound to all-trans retinoic acid. Nature. 1995;378:681–689. doi: 10.1038/378681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, McGrath ME, West BL, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ. A structural role for hormone in the thyroid hormone receptor. Nature. 1995;378:690–697. doi: 10.1038/378690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389:753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greschik H, Moras D. Structure-activity relationship of nuclear receptor-ligand interactions. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:1573–1599. doi: 10.2174/1568026033451736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Wu D, Hwang DJ, Miller DD, Dalton JT. The para substituent of S-3-(phenoxy)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-N-(4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-propionamides is a major structural determinant of in vivo disposition and activity of selective androgen receptor modulators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:230–239. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]