Abstract

The LIM homeodomain (LIM-HD) protein Apterous (Ap) and its cofactor DLDB/CHIP control dorso- ventral (D/V) patterning and growth of Drosophila wing. To investigate the molecular mechanisms of Ap/CHIP function we altered their relative levels of expression and generated mutants in the LIM1, LIM2 and HD domains of Ap, as well as in the LIM-interacting and self-association domains of CHIP. Using in vitro and in vivo assays we found that: (i) the levels of CHIP relative to Ap control D/V patterning; (ii) the LIM1 and LIM2 domains differ in their contributions to Ap function; (iii) Ap HD mutations cause weak dominant negative effects; (iv) overexpression of ChipΔSAD mutants mimics Ap lack-of-function, and this dominant negative phenotype is caused by titration of Ap because it can be rescued by adding extra Ap; and (v) overexpression of ChipΔLID mutants also causes an Ap lack-of-function phenotype, but it cannot be rescued by extra Ap. These results support the model that the Ap–CHIP active complex in vivo is a tetramer.

Keywords: apterous/Chip/Drosophila/Ldb/LIM domain

Introduction

Normal development in multicellular organisms requires regulation of the activity of proteins at many levels. The LIM homeodomain (LIM-HD) transcription factors contain in addition to a specific class of homeodomain, two LIM domains with the potential of modulating their activity through protein–protein interactions. The LIM domains of LIM-HD and nuclear LIM-only proteins interact with a conserved LIM domain-binding factor known as LDB, NLI or CLIM-2. This nuclear protein lacks known conserved motifs found in other proteins, but contains an N-terminal self-association domain (SAD) in addition to a C-terminal LIM-interacting domain (LID) (Breen et al., 1998; Jurata et al., 1998). Thus, LIM-HD and LDB/NLI/CLIM-2 proteins have the capacity to form homo- and heterodimers, as well as higher order complexes formed by two LDB/NLI/CLIM-2 molecules and one or two LIM-HD molecules (Jurata and Gill, 1997; Jurata et al., 1998; Milan and Cohen, 1999; van Meyel et al., 1999).

Although many LIM-HD proteins are involved in cell-fate decisions, they are not related by function. However, most if not all of the specific family members have been conserved from Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila to mammals, suggesting possible conservation of their functions (Hobert and Westphal, 2000). For example, the Drosophila gene apterous (ap) has well defined chicken, mouse and human counterparts (Rodriguez-Esteban et al., 1998; Rincón-Limas et al., 1999). The murine ap ortholog (mLhx2) shows a pattern of expression that is reminiscent of Drosophila ap, and the human counterpart (hLhx2) is functionally interchangeable with the fly gene (Rincón-Limas et al., 1999).

In the Drosophila wing, ap specifies dorsal identity, and its expression defines the dorsal compartment where it functions as a selector gene (Blair, 1993; Diaz-Benjumea and Cohen, 1993; Williams et al., 1993). Regulation of the ap target genes Serrate and fringe initiates a series of cell interactions across the dorso-ventral (D/V) compartment boundary mediated by the Notch/Delta signal transduction pathway. These interactions lead to the activation of the wingless (wg) and vestigial genes, which are required for growth and patterning of the wing (Irvine and Wieschaus, 1994; Kim et al., 1995).

ap function during wing development requires the activity of its cofactor dLdb/Chip, a gene encoding the fly ortholog of the vertebrate LDB/NLI/CLIM-2 proteins (Morcillo et al., 1997; Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998). During wing development, the lack or excess of dLdb/Chip function causes the same phenotype as ap lack-of-function, i.e. D/V transformations, generation of new wing margins and wing outgrowths. Interestingly, the phenotype produced by an excess of dLdb/Chip function can be suppressed by ap overexpression. This result indicates that the stoichiometry of ap and dLdb/Chip is critical, and suggests that in vivo the active complex is a tetramer (Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998). To test this model further, and to investigate the roles of the Apterous (Ap) LIM and HD, and DLDB LID and SAD domains in vivo, we generated ap and Chip constructs carrying mutations in all these protein domains. We tested these constructs in a transcriptional activation assay in cell culture and/or in overexpression and rescue assays in vivo. Our results support the idea that the active complex in vivo is a tetramer, and illustrate the differential contributions of the Ap LIM1 and LIM2 domains to D/V patterning functions. Our observations with mutant dLdb/Chip constructs are similar to results described in two recent papers (Milan and Cohen, 1999; van Meyel et al., 1999).

Results

Generation of Ap mutant constructs

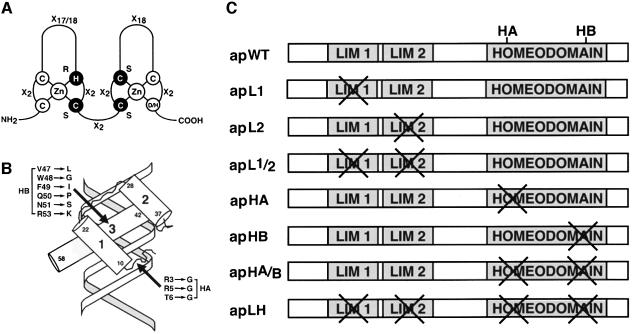

To investigate the function of the LIM domains and the homeodomain in the context of Ap protein function, we generated several Ap constructs in which these motifs were mutated independently or in different combinations. We used site-directed mutagenesis to disrupt the structure of the two zinc-fingers that form each Ap LIM domain (Figure 1A). Three constructs were created that encode Ap proteins containing point mutations within LIM1, LIM2 and both LIM domains; these are referred to as apL1, apL2 and apL1/2, respectively (Figure 1C). We also introduced two different mutations within the Ap homeodomain. The first was designed to change amino acid residues at positions 3, 5 and 6 in the N-terminal arm of the homeodomain (see Figure 1B, and construct apHA in Figure 1C). These residues make contacts in the minor groove of DNA (Kissinger et al., 1990; Gehring et al., 1994). The second homeodomain mutation was designed to change amino acid residues at positions 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 and 53 in the third helix of the homeodomain (see Figure 1B, and construct apHB in Figure 1C). These residues make contacts with the major groove of DNA (Kissinger et al., 1990; Gehring et al., 1994). In addition, we made other constructs combining the mutations described above. Construct apHA/B (Figure 1C) includes the mutations in the N-terminal arm and the third helix of the homeodomain, and construct apLH contains all the mutations described in the LIM domains and homeodomain (Figure 1C).

Fig. 1. Mutations made in the Ap LIM domains and homeodomain. (A) The LIM domain as a double zinc-finger structure (Jurata and Gill, 1998). The amino acids interacting with zinc are indicated by circles. Residues shown in reverse type were mutated (H into R, and C into S) to disrupt the zinc-finger structure. (B) The homeodomain interacting with DNA (Kissinger et al., 1990). Two different regions of the homeodomain were mutated and identified as HA and HB. HA corresponds to mutations made on the N-terminal arm and HB represents mutations made on the third helix. The amino acid substitutions and their corresponding positions are indicated. (C) Structural organization of the ap mutant constructs.

Transcriptional activity of Ap mutants in cultured cells

We used cotransfection assays in Drosophila Schneider-2 (S2) cells (Di Nocera and Dawid, 1983) to investigate the transcriptional activity of the wild-type and mutant Ap proteins described above. S2 cells express Chip, but do not express ap as determined by western and RT–PCR analyses (data not shown).

To drive expression in S2 cells, we generated several effector constructs by placing wild-type and mutant ap cDNAs under the control of the Drosophila actin 5C promoter in the pMK26 vector. The reporter construct was generated by cloning a multimerized 28 bp DNA element that functions as an Ap binding site (Roberson et al., 1994; our unpublished observations) into pAdhCAT, which expresses chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) from the Drosophila Adh distal minimal promoter. The resulting construct is referred to as pGSU-AdhCAT.

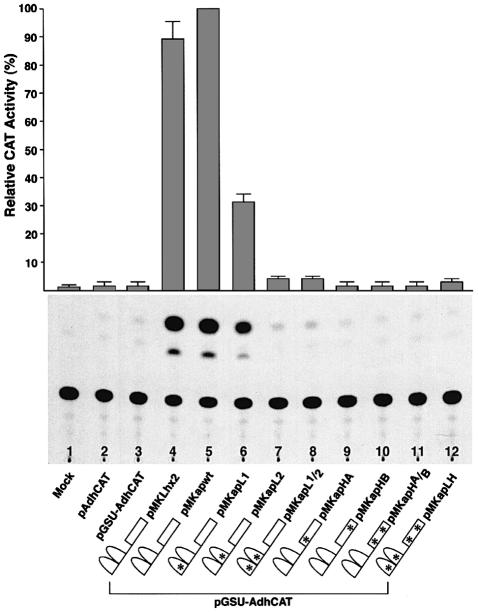

Figure 2 shows that transfection of the reporter construct (pGSU-AdhCAT) into S2 cells produces only background levels of CAT activity (lane 3). Cotransfection of the reporter construct pGSU-AdhCAT with the wild-type Ap effector construct (pMKapwt) results in a high level of CAT activity (lane 5). Interestingly, cotransfection with the Ap effector construct containing mutations in the LIM1 domain (pMKapL1) causes a level of CAT activity three times lower than with the wild-type Ap control (lane 6). Mutations in LIM2 (pMKapL2), or in both LIM domains (pMKapL1/2) reduced the level of CAT activity to background levels (lanes 7 and 8). Similarly, mutations in the Ap homeodomain also decreased CAT activity to background levels (lanes 9–11). As expected, pMKapLH, which served as negative control, produced background levels of CAT activity (lane 12).

Fig. 2. Transcriptional activity of Ap mutant constructs. Drosophila S2 cells were cotransfected with pGSU-AdhCAT and the indicated ap effector constructs. CAT activities relative to that given by the pMKapwt vector alone are shown at the top. Values are the mean (± SEM) of three independent experiments. Details of the assay are given in Materials and methods. Lhx2, which is the vertebrate ortholog of ap, recognizes the GSU regulatory element and was used as a positive control. Mock, cells without transfected DNA. A schematic representation of each effector construct is also shown.

Functional analysis of Ap mutants in ectopic expression assays

Expression of wg along the D/V compartment boundary of the wing imaginal disc provides an assay to investigate the function of Ap mutant proteins in vivo.

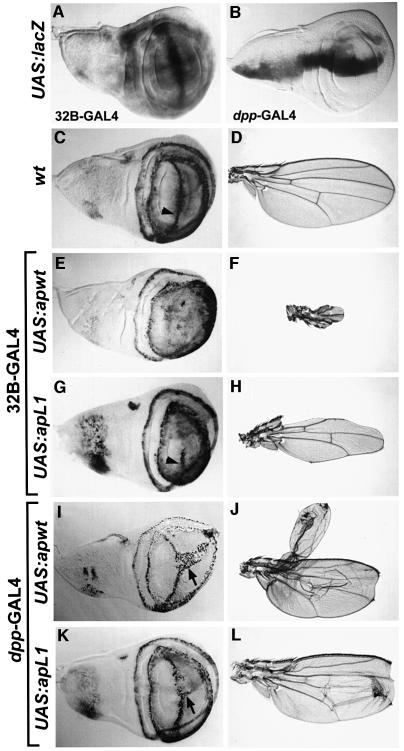

The 32B-GAL4 and dpp-GAL4 drivers (Figure 3A and B) were crossed to upstream activator sequence (UAS) responder lines driving expression of wild-type and mutant Ap proteins. Figure 3C and D shows the wg expression pattern in a wild-type wing disc and the normal morphology of a wild-type wing, respectively. Following ectopic activation of wild-type ap with the 32B-GAL4 driver, the stripe of wg expression along the D/V boundary is abolished (Figure 3E), and the corresponding wings show severe ablation of wing blade tissue (Figure 3F). Expression of the Ap LIM1 mutant from the same driver causes only an interruption of wg expression along the D/V boundary (compare Figure 3G with C and E), and the corresponding wings show considerably more proximo-distal growth (Figure 3H). In contrast to Ap LIM1, ectopic expression of Ap-carrying mutations in LIM2 causes no change in wg expression and does not affect wing morphology (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Functional analysis of wild-type and mutant ap constructs in ectopic assays. Panels show anti-β-gal immunostaining for the wg-lacZ marker following ectopic expression in wing imaginal discs, as well as the resulting phenotypes. (A and B) Wing discs showing UAS-lacZ expression driven by 32B-GAL4 and dpp-GAL4, respectively. (C) Wing disc showing the wg-lacZ wild-type expression. The arrowhead points to the expression domain along the D/V compartment boundary. (D) Wild-type wing. (E and G) Wing discs expressing UAS:apwt and UAS:apL1 from 32B-GAL4, respectively. Note that wild-type ap completely, whereas apL1 partially eliminates the wg-lacZ expression along the D/V boundary. (I and K) Wing discs expressing UAS:apwt and UAS:apL1 from dpp-GAL4, respectively. Note that wild-type ap induces a large stripe of wg-lacZ expression across the ventral compartment, whereas apL1 only induces a small stripe (arrows). (F and H) Wing phenotypes caused by ectopic expression of ap and apL1 using 32B-GAL4, respectively. (J and L) Wing phenotypes caused by ectopic expression of ap and apL1 using dpp-GAL4, respectively.

In a second set of experiments, we crossed all the UAS responder lines to the dpp-GAL4 driver. Expression of wild-type Ap from this driver causes ectopic activation of wg in the ventral compartment along the dpp expression domain (arrow in Figure 3I). The corresponding wings show venation defects, ectopic wing margins, outgrowths on the ventral compartment and a notch at the distal tip of the wing (Figure 3J). Similar ectopic expression of the Ap LIM1 mutant causes a relatively minor activation of wg along the ventral dpp expression domain (arrow in Figure 3K). In this case, the wings also have venation defects and a notch at the distal region, but the outgrowths and ectopic margins on the ventral surface are substantially smaller than those produced by the wild-type Ap protein (Figure 3L). Expression of wg and wing morphology were unaffected when the Ap LIM2 mutant was expressed from dpp-GAL4 (data not shown). See below for the effect of the HD mutation.

Functional analysis of Ap mutants in rescue assays

We took advantage of a GAL4 enhancer detector inserted in the ap locus (Calleja et al., 1996). This mutation, referred to as apGAL4, causes in hemizygosis the lack of wings, sterility and premature death phenotypes characteristic of strong ap mutations. One copy of wild-type ap expressed from a UAS:ap transgene is able to rescue the mutant ap phenotypes (O’Keefe et al., 1998; Rincón-Limas et al., 1999). Thus, the apGAL4 mutant allows us to compare the functions of Ap LIM mutants in a rescue assay.

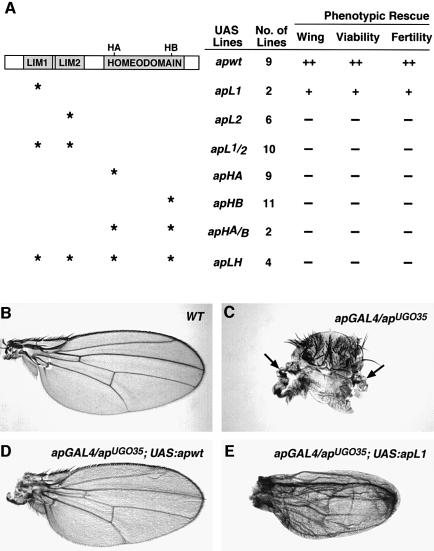

Several independent UAS lines expressing wild-type or mutant Ap proteins were crossed with the apGAL4 driver. The results of these rescue experiments are summarized in Figure 4A. We found that apGAL4/apUGO35 mutant flies expressing Ap LIM2, LIM1/2 or homeodomain mutant constructs do not rescue any of the ap phenotypes and are indistinguishable from apGAL4/apUGO35 control mutant flies. These flies have immature ovaries, are sterile, die within 24–72 h after eclosion and have no wings. In contrast, mutant flies carrying the wild-type control UAS:apwt transgene have wings of virtually normal size and shape (compare Figure 4B and D); these flies also exhibit normal fertility and live an average of 25 days (n = 50). The mutant flies expressing the Ap LIM1 mutant construct show partial rescue of the wing phenotype (Figure 4E). These wings show a clear but never complete rescue (compare with the mutant apGAL4/apUGO35 alone in Figure 4C, and with the mutant rescued with the UAS:apwt control construct in Figure 4D). In addition, these flies live an average of 8 days (n = 50) and, although they are fertile, they usually lay no more than five eggs (n = 30). These differences in rescue abilities by the different constructs could, in principle, be due to abnormal intracellular localization of the mutant proteins or to shortened half-lives. However, using an anti-Ap antibody we found that all mutant proteins accumulate in the nucleus at similar levels (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Functional analysis of Ap mutant proteins. (A) Summary of phenotypic rescues. The ability of each protein to rescue the indicated ap mutant phenotypes is displayed at the right. See the text and Materials and methods for details. Stars indicate the mutation site of the proteins. The number of lines tested per construct is also indicated. ++, complete rescue; +, partial rescue; –, no rescue. (B–E) The rescue results of the wing phenotype. (B) Wing of a wild-type fly. (C) Notum showing the wing phenotype of an apGAL4/apUGO35 mutant fly. Arrows point to wing rudiments. (D) Rescued wing of an apGAL4/apUGO35 fly carrying the UAS:apwt construct. (E) Partially rescued wing phenotype of an apGAL4/apUGO35 fly carrying the UAS:apL1 mutant construct.

In summary, the results of both the ectopic expression and rescue assays are consistent with the transfection experiment data described above. We conclude that the LIM2 domain, like the homeodomain, is absolutely required for Ap function, whereas the LIM1 domain is only required for full activity of the protein.

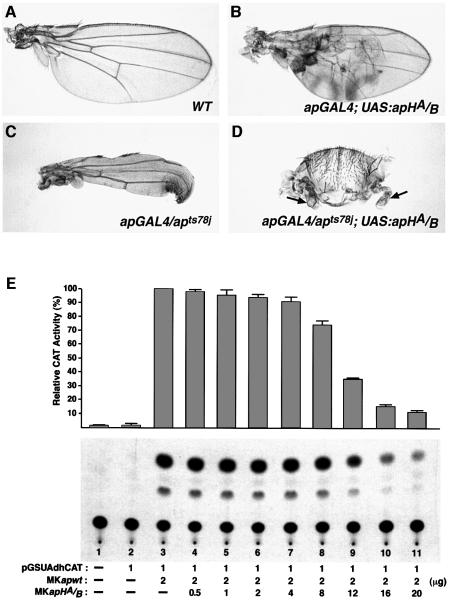

Mutations in the Ap homeodomain behave as weak dominant negatives

Overexpression of Ap HD mutants, as described above, causes somewhat abnormal wings in a small percentage of the flies (and only in the stronger expressing lines). The more obvious abnormalities are blisters and a characteristic pointed shape (Figure 5B, compare with a wild-type wing in Figure 5A). To investigate this phenotype further, an Ap HD mutant protein was expressed in the context of a weak ap mutant (apGAL4/apts78j). At 25°C this mutant lacks most of the wing margin, but shows good proximo-distal growth (Figure 5C). As shown in Figure 5D, the introduction of the Ap HD mutant transgene severely reduces proximo-distal growth and wing size.

Fig. 5. Ap homeodomain mutations behave as weak dominant negatives. (A) Wild-type wing. (B) Wing of an apGAL4; UAS:apHA/B fly. Note the blistering and the pointed shape of the wing. (C) Wing of an apGAL4/apts78j fly. (D) Wing of an apGAL4/apts78j; UAS:apHA/B fly. Note that the size of the wing (arrows) is greatly reduced. (E) ApHA/B impairs Ap transcriptional activity at high concentration. S2 cells were cotransfected with a fixed amount of an Ap expression vector (pMKapwt) and increasing amounts of a vector expressing an Ap homeodomain mutant protein (pMKapHA/B). Note the relatively high concentration of ApHA/B required to reduce Ap transcriptional activity to basal levels. CAT activities relative to that produced by transfecting with the pMKapwt vector alone are shown at the top. Values are the mean (± SEM) of three independent experiments. Various amounts of a carrier plasmid (pMK26) were added to equalize the amount of transfected DNA.

We also tested the effects of Ap HD mutant protein in the transcriptional activation assay described above by cotransfecting a fixed amount of an Ap effector vector (pMKapwt) with increasing amounts of a vector carrying mutations in the Ap homeodomain (pMKapHA/B). Figure 5E shows that, in this assay, the Ap HD mutant protein is able to impair wild-type Ap transcriptional activity, but only when present at a relatively high concentration. In parallel experiments, pMKapLH, which carries mutations in LIM domains and homeodomain, did not affect Ap transcriptional activity (data not shown).

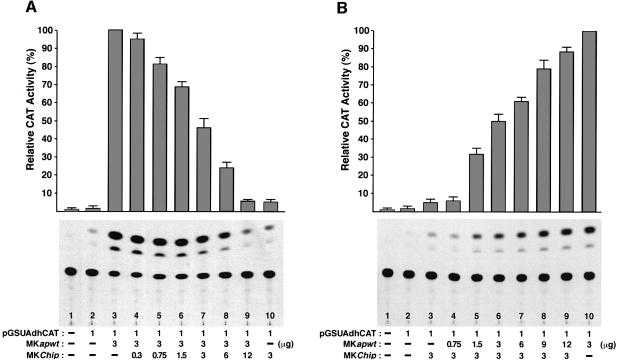

CHIP/DLDB modulates the levels of Ap transactivation in a dosage-dependent manner

Transfection studies in S2 cells were carried out to determine whether the activity of Ap as a transcriptional activator is modified by the level of its cofactor CHIP/DLDB.

First, we investigated whether the CAT activity produced by a fixed amount of a wild-type ap effector construct (pMKapwt) could be modified by adding increasing amounts of a second effector construct expressing Chip (pMKChip). Thus, S2 cells were cotransfected with the reporter vector (pGSUAdhCAT) and different relative amounts of the two effector constructs. Because there is a basal level of endogenous CHIP/DLDB protein in S2 cells, as shown by western analysis (data not shown), the CAT activity from each transfection was expressed relative to the activity obtained when the ap expression vector was transfected alone (100%). As shown in Figure 6A, increasing the concentration of the Chip effector construct gradually decreases CAT activity. When both expression vectors are cotransfected in a 1:1 molar ratio, CAT activity is reduced to half the level observed when transfecting with the ap expression vector alone (compare lanes 3 and 7, Figure 6A). However, when ap and Chip constructs are respectively transfected in a 1:4 molar ratio, CAT activity is reduced (16-fold) to a level similar to that produced by transfecting with the Chip effector construct alone (compare lanes 9 and 10, Figure 6A).

Fig. 6. CHIP/DLDB controls Ap transcriptional activity in a dosage-dependent manner. (A) An excess of CHIP diminishes Ap transcriptional activity. S2 cells were cotransfected with a fixed amount of an ap expression vector (MKapwt) and increasing amounts of a vector expressing Chip (MKChip). Note that an increase in the concentration of CHIP reduces Ap transcriptional activity. (B) The addition of Ap overcomes the inhibitory effect produced by excess CHIP. A fixed amount of pMKChip was cotransfected with increasing amounts of pMKapwt. Note that an augmentation in the concentration of Ap gradually restores CAT activity. CAT activities relative to that produced by transfecting with the pMKapwt vector alone are shown at the top. Values are the mean (± SEM) of three independent experiments. Various amounts of a carrier plasmid (pMK26) were added to equalize the amount of transfected DNA.

In a second set of experiments, we asked whether the lack of CAT activity caused by an excess of Chip expression could be overcome by increasing the amounts of ap effector construct. In this experiment, a fixed amount of CHIP was produced together with variable amounts of Ap. Figure 6B shows that when the ap and Chip expression vectors are cotransfected at a 1:4 molar ratio, the CAT activity is reduced 14-fold compared with the activity obtained by transfecting with the ap expression vector alone (compare lanes 4 and 10). Lanes 5–9 show that gradual increases in the concentration of Ap cause concomitant increases in CAT activity. If the molar ratio of effector construct is reverted and ap is cotransfected at 4-fold molar excess relative to Chip, the resulting CAT activity approximates the activity obtained by transfecting ap alone (compare lanes 9 and 10, Figure 6B). Thus, these results argue that CHIP/DLDB is a saturable factor that regulates the activity of Ap as a transcriptional activator in a dosage-dependent manner.

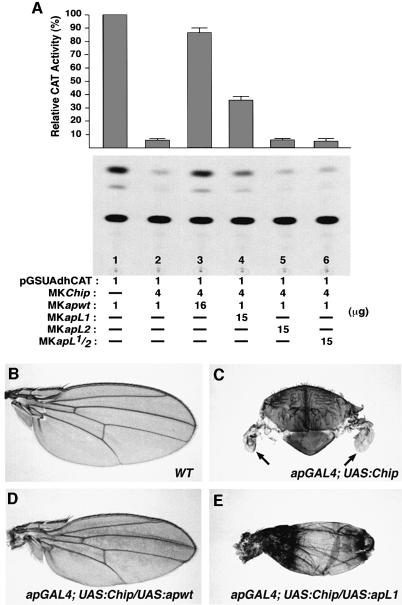

Functional analysis of the LIM domains in the context of Ap–CHIP interactions

We investigated the requirement of each Ap LIM domain for the dosage-dependent interactions between Ap and CHIP observed in the cotransfection experiments described above. The transcriptional activity of Ap is abolished by an excess of CHIP, and transcriptional activation is restored by adding extra wild-type Ap (see Figure 6, and lanes 1–3 in Figure 7A). This observation provided us with a transcriptional activity assay to investigate the function of the LIM domains on Ap–CHIP interactions. Lane 4 in Figure 7A shows that adding extra Ap carrying a mutated LIM1 and an intact LIM2 domain restores transcriptional activation, but only partially. In contrast, adding extra Ap-carrying mutations in the LIM2 domain alone (lane 5 in Figure 7A), or in both LIM1 and LIM2 domains (lane 6 in Figure 7A) does not restore activation.

Fig. 7. Different requirements for the LIM1 and LIM2 domains in Ap–CHIP interactions. (A) The LIM2 domain is most important for Ap transcriptional activity. S2 cells were cotransfected with MKapwt and MKChip at a 1:4 molar ratio, plus a similar excess of MKapL1, MKapL2 and MKapL1/2. An excess of MKapwt was also added as positive control. CAT activities relative to that produced by transfecting with the MKapwt vector alone are shown at the top. Values are the mean (± SEM) of three independent experiments. Various amounts of a carrier plasmid were added to equalize the amount of transfected DNA. (B–E) The LIM2 domain is absolutely required for Ap–CHIP interactions in vivo. (B) Wild-type wing. (C) Notum showing the wing rudiments (arrows) of an apGal4/+; UAS:Chip/+ fly. Note the severe reduction in the size of the wings caused by overexpression of Chip. (D) Wing of an apGal4/+; UAS:Chip/UAS:apwt fly. (E) Wing of an apGal4/UAS:apL1; UAS:Chip/+ fly. Note that the phenotype caused by Chip overexpression is completely and partially rescued by the UAS:apwt (D) and UAS:apL1 (E) constructs, respectively.

To investigate the relevance of these findings in vivo, we used GAL4/UAS constructs in transgenic animals. As shown in Figure 7C (see also Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998), an excess of Chip expression from the ap promoter (apGAL4/+; UAS:Chip/+) leads to a severe reduction of the wing blades. This phenotype can be rescued by adding one copy of a wild-type ap transgene (apGAL4/+; UAS:Chip/+; UAS:apwt/+) (Figure 7D, compare with a wild-type wing in Figure 7B). In accordance with the cotransfection experiments described above, the excess-of-Chip wing phenotype is partially rescued with one copy of an ap LIM1 mutant transgene (Figure 7E), but is not rescued by any ap transgene carrying mutations in LIM2, or LIM1 and LIM2 (data not shown).

To summarize, in the context of Ap–CHIP interactions, we found functional differences between the two Ap LIM domains. In both the transcriptional and rescue assays, LIM2 is absolutely required, whereas LIM1 is only partially required for Ap–CHIP interactions.

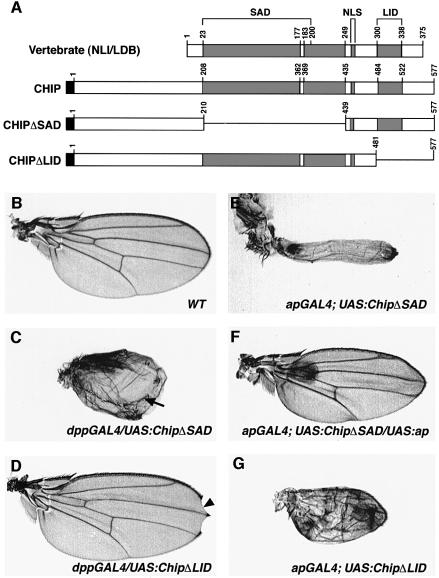

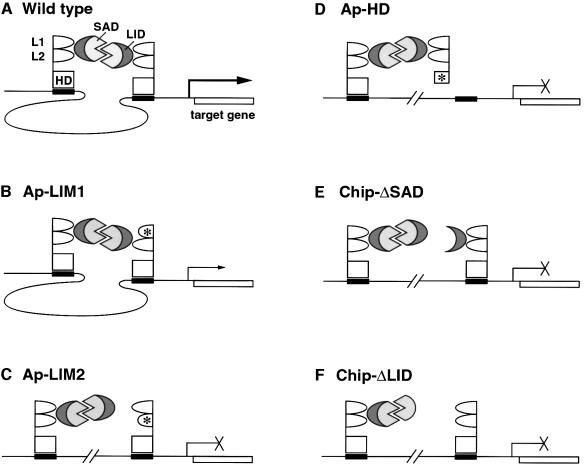

Functional analysis of the LID and SAD domains of CHIP

To investigate the roles of the LID and SAD domains of CHIP in the context of Ap/CHIP functions, we generated the constructs shown in Figure 8A. The activity of these mutant CHIP proteins was investigated in overexpression experiments using the dppGAL4 and apGAL4 drivers.

Fig. 8. Functional analysis of CHIP mutants. (A) The CHIP deletion constructs. For comparison, the location of the major blocks of homology between the vertebrate NLI/LDB and its Drosophila ortholog CHIP are shown in shaded boxes. The vertebrate SAD, NLS (nuclear localization signal) and LID motifs are indicated by brackets. The CHIP deletions are represented by continuous lines and the positions of the corresponding amino acids are indicated. Black boxes represent human Myc epitope tags introduced within the UAS vector for monitoring expression. (B–G) In vivo analysis of the LID and SAD domains of CHIP. (B) Wild-type wing. (C) Wing phenotype caused by overexpression of ChipΔSAD from the dppGAL4 driver; the arrow points to the ectopic margin. (D) Wing phenotype caused by dppGAL4 overexpression of ChipΔLID; the arrow points to the nicking of the wing. (E) Wing phenotype resulting from overexpression of ChipΔSAD with the apGAL4 driver. Note the severe reduction in the size of the wing. (F) Rescued wing phenotype of a fly overexpressing ChipΔSAD and ap from the apGAL4 driver. (G) Wing phenotype caused by overexpression of ChipΔLID from the apGAL4 driver.

Using dppGAL4, overexpression of ChipΔSAD causes the formation of a new margin along the dpp expression domain, and a lack of proximo-distal growth (Figure 8C). This is the same phenotype caused by overexpression of wild-type Chip. Overexpression of ChipΔLID causes a milder phenotype characterized by nicking of the distal wing margin (Figure 8D). For comparison, a wild-type wing is shown in Figure 8B.

Using apGAL4, overexpression of ChipΔSAD also causes phenotypes similar to those caused by overexpression of wild-type Chip. These phenotypes are characterized by severe reduction or elimination of the wing (Figure 8E), and in extreme cases by reduction of the notum and poor fusion of the two heminotums (data not shown). Because both the wild-type CHIP and CHIPΔSAD proteins have intact LID domains, one possibility is that their overexpression phenotype is caused by titration of Ap. This hypothesis is supported by the rescue of this phenotype by simultaneous overexpression of ap (Figure 8F). On the other hand, overexpression of ChipΔLID causes wings of a reduced size that show severe blistering (Figure 8G). However, unlike ChipΔSAD, the phenotype caused by ChipΔLID overexpression cannot be rescued by simultaneous overexpression of ap (data not shown).

Discussion

LDB proteins bind LIM domains of LIM-HD (and nuclear LIM-only) proteins. This raises the possibility that, in vivo, LDB proteins function as LIM-HD cofactors with the potential of modulating their activity. Analysis of the fly ortholog DLDB/CHIP during wing development supports this idea because of the following two observations: (i) dLdb/Chip lack-of-function causes the same phenotype as ap lack-of-function; (ii) the excess of dLdb/Chip causes the same ap lack-of-function phenotype, and it can be rescued by simultaneous overexpression of ap. Thus, it was proposed that the functional complex carrying out D/V patterning functions is a tetramer (Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998).

To investigate the roles of the LIM, HD, SAD and LID domains of Ap and CHIP in the context of D/V patterning functions, we generated constructs containing mutations in all these domains. The activity of these mutant proteins was investigated in vivo and in transcriptional activation assays to test the tetramer model and the idea that the stoichiometry of Ap and CHIP is critical for wing D/V patterning.

We found that mutations in the LIM domains reduce or abolish the activity of Ap. These results are in contrast with the overexpression of wild type and Xlim1 LIM mutants in Xenopus (Taira et al., 1994). In these experiments, the LIM mutants showed a much stronger organizing activity than the wild-type protein. Obviously, the two experimental systems are very different. However, one possibility is that the discrepancy may reflect differences between the mechanisms of action of the Ap and XLIM1 proteins. Thus, it would be interesting to carry out similar experiments with the Ap frog ortholog or with the fly XLIM1 ortholog. In support of the idea of intrinsic differences between different LIM-HD proteins are the observations that different LIM-HD proteins behave differently with respect to DNA binding in vitro. For example, it was reported that LIM domain mutants of ISL1, MEC3 and LHX3 bind DNA better than the corresponding wild-type proteins (Sánchez-García et al., 1993; Xue et al., 1993; Bach et al., 1995). However, this was not the case for ISL1, ISL2 and LMX1 (German et al., 1992; Gong and Hew, 1994; Wang and Drucker, 1995; Jurata and Gill, 1997).

Our observations with Ap LIM domain mutants are in accordance with the results of O’Keefe et al. (1998), in which a deleted Ap protein was produced that lacked amino acids 148–260, including both LIM domains. Because we generated point mutations in either one or both LIM domains, we were able to evaluate the requirements of each of them for Ap function. We found that whereas LIM2 is absolutely required, LIM1 is only required for full Ap activity (Figures 2–4). In the context of CHIP/Ap interactions, we found the same functional difference between LIM1 and LIM2 (Figure 7). This indicates that the LIM2 domain is the principal mediator of the interaction with CHIP. Our results in vivo are consistent with other observations in vitro identifying differences among LIM domains in their interactions with LDB/NLI/CLIM proteins. For instance, LDB/NLI/CLIM shows a strong binding preference for the LIM1 of ISL1 and LMO2, but the LIM2 of MEC3 and LMX1 (Jurata et al., 1996; Jurata and Gill, 1997). Differences between LIM1 and LIM2 domains have also been reported in the context of the interaction between the LIM-only protein MLP and the actin cytoskeleton (Arber and Caroni, 1996), and in the context of the interaction between LMX1 and the bHLH protein E47/Pan-1 (Johnson et al., 1997; see also the review by Jurata and Gill, 1998).

Mutations in homeodomain amino acids that make contacts with either the major or minor groove of DNA result in a complete lack of Ap activity in the tested assays. Thus, unlike the case of the fushi-tarazu homeodomain protein that carries out some of its functions by interacting with other proteins (Copeland et al., 1996), it seems likely that binding to DNA is essential for Ap activities.

The model that the functional Ap–CHIP complex is a tetramer formed by two Ap molecules bridged by two CHIP molecules makes certain predictions, which are discussed below (see also Figure 9). First, it predicts that the stoichiometry of Ap and CHIP is critical for complex formation. Too little Ap or CHIP, or an excess of CHIP will result in the formation of trimers or other inactive complexes. In contrast, excess Ap, at least within limits, should not preclude formation of the tetramer because it should not affect CHIP interacting with itself. The results of our previous in vivo experiments overexpressing Ap and CHIP were in accordance with the predictions of the model (Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998), but the assay was not quantitative. Here, by performing cotransfection experiments with various ratios of Ap and CHIP, we demonstrated that CHIP modulates Ap activity in a dosage-dependent manner (Figure 6).

Fig. 9. Ap and CHIP mutants in the context of the tetramer model (A). Two CHIP molecules interact with each other through their SAD domains and bridge two Ap molecules through interactions between the CHIP LID and Ap LIM domains. The CHIP homodimer may be required for bringing together distant Ap-binding sites and/or for facilitating contacts with target promoters to activate downstream genes. (B) Ap LIM1 is only required for full Ap activity. Thus, the LIM1 domain may stabilize the tetramer complex. In Ap LIM1 mutants, the complex would form, but it would be less efficient at regulating target genes. (C) Ap LIM2 is absolutely required for interactions with CHIP LID. Thus, Ap LIM2 mutations are likely to disrupt the complex. (D) Mutations in Ap HD behave as dominant negatives. As indicated in the figure, they are likely to result in the formation of non-functional complexes. Our experiments show that a higher concentration of wild-type Ap overcomes this dominant negative effect. (E) Deletion of the CHIP SAD motif should lead to the titration of Ap. In this context, we showed that the addition of Ap rescues the CHIPΔSAD overexpression phenotype, probably by transforming abnormal trimeric complexes into functional tetramers. (F) Deletion of the CHIP LID domain should also cause formation of non-functional trimers due to recruitment of CHIP molecules that cannot interact with Ap LIM domains. In this context, we showed that the addition of Ap does not rescue the CHIPΔLID overexpression phenotype.

Our observations on the behavior of Ap HD mutants also fulfill the prediction of the tetramer model that these mutants should behave as dominant negatives by generating non-functional complexes (Figure 9D). We found that HD mutants are weak dominant negatives (see Figure 5). This is in contrast to the strong dominant negative effects described by O’Keefe et al. (1998). The difference between these results may be a consequence of the nature of the mutations: we generated point mutants, whereas O’Keefe et al. (1998) generated a truncated protein lacking the HD and the C-terminal part of the protein.

The tetramer model also predicts that CHIPΔSAD mutants should behave as wild-type CHIP in overexpression experiments (Figure 9E). This is because these mutants, like wild-type CHIP, should interact normally with Ap, thus making it not available for the formation of functional tetramers. As in the case of wild-type Chip, the phenotype produced by extra CHIPΔSAD can be rescued by Ap overexpression (Figure 8F).

We find that overexpression of the CHIPΔLID mutant produces a dominant negative phenotype, presumably because this mutant interferes with the formation of a functional tetramer (Figure 9F). Also in agreement with the model, we find that this phenotype is not rescuable by extra Ap (data not shown).

The idea that LIM-HD proteins function as dimers bridged by dimers of LDB molecules is attractive because it opens many possibilities for regulation. As shown here, one possibility is to alter the amount of LDB. Additional factors may compete for the interaction between LIM-HD and LDB proteins, as in the case of LMO (Milan et al., 1998; Milan and Cohen, 1999) and R-LIM (Bach et al., 1999). Alternatively, as yet unknown factors may compete for the interaction between the two LDB proteins. The tetramer model also opens the possibility of combinations of different LIM-HD proteins forming a single tetramer, thus regulating new sets of target genes.

Materials and methods

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis

To prepare a DNA template for mutagenesis (pBSapwt), the full ap openreading frame (ORF) was isolated from pUAS:ap (Rincón-Limas et al., 1999) and subcloned into pBSKS(–) via NotI–XbaI sites. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the In Vitro Muta-Gene System Version 2 from Bio-Rad. Four plus-strand oligonucleotides were used to mutagenize Ap LIM domains and homeodomain. To disrupt the formation of the two zinc-finger structures of each Ap LIM domain, the consensus amino acid residues -H-X2-C-X2-C-X2-C-, which comprise only four out of the eight ligand residues for metal binding (see Figure 1A), were simultaneously changed to -R-X2-S-X2-S-X2-S-. To disrupt DNA contacts with the N-terminal arm of the homeodomain, amino acid residues R3, R5 and T6 were simultaneously changed to G3, G5 and N6 (Figure 1B). To disrupt DNA contacts with the third helix of the homeodomain, residues V47, W48, F49, Q50, N51 and R53 were simultaneously changed to L47, G48, I49, P50, S51 and K53 (Figure 1B). The sequences of the four oligonucleotides are:

LIM1: AAACGGTGGCGTGCAAGTTCCCTACAGTCCTACGCCTGTCGGCAGCCG;

LIM2: CTTGTTTTTCACGTCAACTCCTTCTGCTCCACTGTCTCCCACACGCCA;

HA: CGCACCAAAGGAATGGGAAACTCGTTT;

HB: GTCCTACAGCTCGGGATTCCAAGTGCAAAGGCCAAATGG.

All sequences are written 5′ to 3′ and the bases changed from wild type are underlined. Once generated, all mutations were confirmed by sequencing the whole coding region of the corresponding mutant clones (Figure 1C).

Plasmid constructions

For transfection experiments, the NotI–XbaI inserts from pBSapwt and its derivative mutants (Figure 1C) were subcloned into the EcoRV site of pMK26. The resulting plasmids were identified as pMKapwt, pMKapL1, pMKapL2, pMKapL1/2, pMKapHA, pMKapHB, pMKapHA/B and pMKapLH. Similarly, a 1.8 kb fragment containing the full dLdb/Chip ORF (Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998) was inserted into the same site of pMK26 to generate pMKChip. pMK26 (also known as pACTSV40BS, a gift from David Hogness, Stanford University, CA) is an expression vector that expresses cDNAs under the control of the 2.6 kb Drosophila actin 5C promoter.

To generate the parental reporter vector, the 4.8 kb EcoRI Ubx/lacZ/SV40 cassette was removed from pMK42 (also known as pAdh/Bgal, a gift from David Hogness, Stanford University, CA) and replaced with a 1.6 kb SmaI–SacI fragment from pC4CAT (Thummel et al., 1988). The resulting vector, referred to as pAdhCAT, has a polylinker (unique sites for HindIII, SphI, PstI, SalI and XbaI) followed by the Drosophila Adh distal promoter (–34 to +53) fused to the CAT gene. pGSU-AdhCAT was constructed by cloning nine tandem copies of the sequence 5′-ATATCAGGTACTTAGCTAATTAAATGTG-3′ into the polylinker of pAdhCAT. This sequence corresponds to the Lhx2 binding site present in the pituitary glycoprotein basal element (PGBE) of the mouse glycoprotein hormone α-subunit gene (Roberson et al., 1994).

The ap mutant cDNAs (Figure 1C) were also subcloned into the NotI–XbaI sites of pUAST (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). The resulting vectors were identified as pUAS:apL1, pUAS:apL2, pUAS:apL1/2, pUAS:apHA, pUAS:apHB, pUAS:apHA/B and pUAS:apLH (Figure 4A).

To generate UAS:Chip mutants, we first cloned the full-length dLdb/Chip cDNA into the pUASM vector, which is essentially pUAST carrying six human Myc tags at the BglII site. The resulting construct was used as PCR template to create a vector lacking sequences for amino acids 210–439. This construct was referred to as pUAS:ChipΔSAD. Similarly, a construct lacking sequences for amino acids 481–577 was also created and identified as pUAS:ChipΔLID. Both clones were confirmed by sequencing the whole coding region. DNA manipulations were carried out by standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989) and all plasmids were prepared using the Qiagen Maxi Kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA).

Cell culture and DNA transfections

Drosophila S2 cells were cultured as outlined (Di Nocera and Dawid, 1983; Krasnow et al., 1989) except that cells were maintained at 26°C in air. Transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate precipitation technique as described (Di Nocera and Dawid, 1983; Rio and Rubin, 1985; Krasnow et al., 1989), with minor modifications. Briefly, 200 µl of 0.25 M CaCl2 containing 20–22 µg of plasmids were added drop by drop into a 2 ml Eppendorf tube containing 200 µl of 2× HEPES-buffered saline (HeBS) solution pH 7.05. After 30 min at room temperature, coprecipitates were added to cultured cells. Following 20 h of incubation, the DNA–calcium phosphate was removed and cells were further incubated in fresh medium for a total of 40–44 h. For transfections shown in Figure 2, 1 µg of pGSU-AdhCAT was combined with 10 µg of the indicated effector plasmids and 9 µg of empty pMK26 to bring the total amount of DNA to 20 µg. For competition experiments, 1 µg of pGSU-AdhCAT was mixed with different amounts of pMK effector vectors as indicated in Figures 5–7. Various amounts of empty pMK26 were added to ensure that the total amount of transfected DNA was the same. In all cases, 500 ng of pcopβgal were used to normalize transfection efficiencies. All experiments were performed three times using two different plasmid preparations.

CAT assays

Cells were harvested and lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing. Equal amounts of protein, as determined with the Bio-Rad Bradford Kit, were used to normalize transfection efficiency by β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity. Following normalization of cell extracts, CAT assays were performed essentially as described (Gorman et al., 1982). All assays were performed within the linear range of activities with respect to incubation time and sample concentration. The labeled acetylated products were separated by thin-layer chromatography and spots were quantitated using the PhosphorImager SF from Molecular Dynamics. For each transfection, CAT activity was expressed relative to the activity produced by pMKapwt.

Drosophila stocks and crosses

pUAS vectors encoding Ap mutants were transformed into yw; apUGO35/CyOwglacZ mutant embryos by standard techniques (Rubin and Spradling, 1982). The UAS:ap and UAS:Chip lines have recently been described (Fernández-Fúnez et al., 1998; Rincón-Limas et al., 1999). The UAS:Chip mutant constructs were transformed into yw embryos (Rubin and Spradling, 1982). For ectopic analyses, UAS lines encoding wild-type and mutant Ap proteins were crossed to 32B-GAL4 (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) and dppGAL4 (Bloomington Stock Center, Bloomington, IN). For rescue of ap mutant phenotypes, the wild-type and mutant UAS:ap transgenes were crossed to apGAL4MD544/CyOwglacZ and mutant progenies were scored for phenotypic rescues. To rescue the wing phenotype caused by overexpression of Chip, flies carrying apGAL4MD544 and UAS transgenes encoding wild-type and mutant Ap proteins were crossed to UAS:Chip flies. The UAS:Chip mutant constructs were analyzed by inducing their overexpression with the dppGAL4 and apGAL4 drivers. Wings and notums were dissected from adult females, mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific) and photographed with the same magnification. β-gal immunodetection and X-gal staining were conducted as described (Rincón-Limas et al., 1999).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Scot Munroe and the D.Hogness laboratory for S2 cells and pMK expression vectors, and the Bloomington Stock Center for Drosophila strains. We are also grateful to Marty Shea, Kimberly Raney and members of the laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. D.E.R.-L., C.-H.L. and I.C. were supported by a PEW postdoctoral fellowship, the Baylor Graduate Program in Developmental Biology, and a short-term fellowship from the Comunidad Autonoma de Madrid, respectively. This work was supported by NIH grant GM55681 to J.B.

References

- Arber S. and Caroni,P. (1996) Specificity of single LIM motifs in targeting and LIM/LIM interactions in situ. Genes Dev., 10, 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I., Rhodes,S.J., Pearse,R.V.I., Heinzel,T., Gloss,B., Scully,K.M., Sawchenko,P.E. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (1995) P-Lim, a LIM homeodomain factor, is expressed during pituitary organ and cell commitment and synergizes with Pit-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 2720–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I. et al. (1999) RLIM inhibits functional activity of LIM homeodomain transcription factors via recruitment of the histone deacetylase complex. Nature Genet., 22, 394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S.S. (1993) Mechanisms of compartment formation: Evidence that non-proliferating cells do not play a role in defining the D/V lineage restriction in the developing wing of Drosophila. Development, 119, 339–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. and Perrimon,N. (1993) Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development, 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen J.J., Agulnick,A.A., Westphal,H. and Dawid,I.B. (1998) Interaction between LIM domains and the LIM domain binding protein Ldb1. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 4712–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja M., Moreno,E., Pelaz,S. and Morata,G. (1996) Visualization of gene expression in living adult Drosophila. Science, 274, 252–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J.W., Nasiadka,A., Dietrich,B.H. and Krause,H.M. (1996) Patterning of the Drosophila embryo by a homeodomain-deleted Ftz polypeptide. Nature, 379, 162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Benjumea F. and Cohen,S.M. (1993) Interaction between dorsal and ventral cells in the imaginal disc directs wing development in Drosophila. Cell, 75, 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nocera P.P. and Dawid,I.B. (1983) Transient expression of genes introduced into cultured cells of Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 80, 7095–7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fúnez P., Lu,C.-H., Rincón-Limas,D.E., García-Bellido,A. and Botas,J. (1998) The relative expression amounts of apterous and its co-factor dLdb/Chip are critical for dorso-ventral compartmentalization in the Drosophila wing. EMBO J., 17, 6846–6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring W.J., Qian,Y.Q., Billeter,M., Furukubo-Tokunaga,K., Schier,A.F., Resendez-Perez,D., Affolter,M., Otting,G. and Wüthrich,K. (1994) Homeodomain–DNA recognition. Cell, 78, 211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German M.S., Wang,J., Chadwick,R.B. and Rutter,W.J. (1992) Synergistic activation of the insulin gene by a LIM-homeo domain protein and a basic helix–loop–helix protein: building a functional insulin minienhancer complex. Genes Dev., 6, 2165–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z. and Hew,C.L. (1994) Zinc and DNA binding properties of a novel LIM homeodomain protein Isl-2. Biochemistry, 33, 15149–15158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman C.M., Moffat,L.F. and Howard,B.H. (1982) Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 2, 1044–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. and Westphal,H. (2000) Functions of LIM-homeobox genes. Trends Genet., 16, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine K.D. and Wieschaus,E. (1994) fringe, a boundary-specific signaling molecule, mediates interactions between dorsal and ventral cells during Drosophila wing development. Cell, 79, 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.D., Zhang,W., Rudnick,A., Rutter,W.J. and German,M.S. (1997) Transcriptional synergy between LIM-homeodomain proteins and basic helix–loop–helix protein: the LIM2 domain determines specificity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 3488–3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W. and Gill,G.N. (1997) Functional analysis of the LIM domain interactor NLI. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5688–5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W. and Gill,G.N. (1998) Structure and function of LIM domains. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., 228, 75–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W., Kenny,D.A. and Gill,G.N. (1996) Nuclear LIM interactor, a rhombotin and LIM homeodomain interacting protein, is expressed early in neuronal development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11693–11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W., Pfaff,S.M. and Gill,G.N. (1998) The nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI mediates homo- and heterodimerization of LIM domain transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3152–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Irvine,K.D. and Carroll,S.B. (1995) Cell recognition, signal induction, and symmetrical gene activation at the dorsal–ventral boundary of the developing Drosophila wing. Cell, 82, 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger C.R., Liu,B., Martin-Blanco,E., Kornberg,T.B. and Pabo,C.O. (1990) Crystal structure of an engrailed homeodomain–DNA complex at 2.8 Å resolution: A framework for understanding homeodomain–DNA interactions. Cell, 63, 579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnow M.A., Saffman,E.E., Kornfeld,K. and Hogness,D.S. (1989) Transcriptional activation and repression by Ultrabithorax proteins in cultured Drosophila cells. Cell, 57, 1031–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan M. and Cohen,S.M. (1999) Regulation of LIM homeodomain activity in vivo: a tetramer of dLDB and Apterous confers activity and capacity for regulation by dLMO. Mol. Cell, 4, 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan M., Diaz-Benjumea,F.J. and Cohen,S.M. (1998) Beadex encodes an LMO protein that regulates Apterous LIM-homeodomain activity in Drosophila wing development: a model for LMO oncogene function. Genes Dev., 12, 2912–2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo P., Rosen,C., Baylies,M.K. and Dorsett,D. (1997) Chip, a widely expressed chromosomal protein required for segmentation and activity of a remote wing margin enhancer in Drosophila. Genes Dev., 11, 2729–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe D.D., Thor,S. and Thomas,J.B. (1998) Function and specificity of LIM domains in Drosophila nervous system and wing development. Development, 125, 3915–3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincón-Limas D.E., Lu,C.H., Canal,I., Calleja,M., Rodriguez-Esteban,C., Izpisúa-Belmonte,J.C. and Botas,J. (1999) Conservation of the expression and function of apterous orthologs in Drosophila and mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 2165–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio D.C. and Rubin,G.M. (1985) Transformation of cultured Drosophila melanogaster cells with a dominant selectable marker. Mol. Cell. Biol., 5, 1833–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson M.S., Schoderbek,W.E., Tremml,G. and Maurer,R.A. (1994) Activation of the glycoprotein hormone α-subunit promoter by a LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 2985–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Esteban C., Schwabe,J.W.R., De La Peña,L., Rincón-Limas,D.E., Magallon,J., Botas,J. and Izpisúa-Belmonte,J.C. (1998) Lhx2, a vertebrate homologue of apterous, regulates vertebrate limb outgrowth. Development, 125, 3925–3934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin G.M. and Spradling,A.C. (1982) Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science, 218, 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García I., Osada,H., Forster,A. and Rabbitts,T.H. (1993) The cysteine-rich LIM domains inhibit DNA binding by the associated homeodomain in Isl-1. EMBO J., 12, 4243–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira M., Otanl,H., Saint-Jeannet,J. and Dawid,I.B. (1994) Role of the LIM class homeodomain protein Xlim-1 in neural and muscle induction by the Spemann organizer in Xenopus. Nature, 372, 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel C.S., Boulet,A.M. and Lipshitz,H.D. (1988) Vectors for Drosophila P-element-mediated transformation and tissue culture transfection. Gene, 74, 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meyel D.J., O’Keefe,D.D., Jurata,L.W., Thor,S., Gill,G.N. and Thomas,J.B. (1999) Chip and Apterous physically interact to form a functional complex during Drosophila development. Mol. Cell, 4, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. and Drucker,D.J. (1995) The LIM domain homeobox gene isl-1 is a positive regulator of islet cell-specific proglucagon gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 12646–12652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.A., Paddock,S.W. and Carroll,S.B. (1993) Pattern formation in a secondary field: a hierarchy of regulatory genes subdivides the developing Drosophila wing disc into discrete subregions. Development, 117, 571–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue D., Tu,Y. and Chalfie,M. (1993) Cooperative interactions between the Caenorhabditis elegans homeoproteins UNC-86 and MEC-3. Science, 261, 1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]