Abstract

The relationships between key features of the cardiac electrical activity, such as electrical restitution, discordant alternans, wave break and reentry, and the onset of ventricular tachyarrhythmias have been characterized extensively under the condition of constant, rapid pacing. However, it is unlikely that this scenario applies directly to the clinical situation, where the induction of ventricular tachycardia typically is associated with the interruption of normal cardiac rhythm by several premature beats. To address this issue, we have developed a general theory to explain why specific patterns of premature stimuli increase dynamic heterogeneity of repolarization and precipitate conduction block. The theory predicts that conduction block is caused by: (1) creation of a spatial gradient in diastolic interval (DI) by waves traveling at slightly different velocities (i.e., conduction velocity dispersion), and (2) amplification of the spatial gradient in DI over subsequent action potentials, secondary to a strong dependence of action potential duration (APD) on the preceding DI (i.e., a steep APD restitution function). Tests of this theory have been conducted in computer models of homogeneous tissue, where increased spatial dispersion of repolarization during premature stimulation can be assigned solely to the development of dynamical heterogeneity, and a canine model of spontaneously occurring ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Our results thus far indicate that the probability of inducing VF in the animal model is highest for those sequences predicted to cause conduction block in the computer model. An understanding of the mechanisms underlying these observations will help to identify key electrical phenomena in the onset of ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. Drug and electrical therapies can then be improved by targeting these specific phenomena.

Electrical restitution and spatial dispersion of repolarization

Given that sudden cardiac death remains the leading cause of death in the US, the mechanisms underlying the development of VF continue to be an area of intense scientific interest. Although several theories regarding the cellular electrophysiologic mechanism for VF currently are being evaluated1–3, substantial evidence has accumulated over the last few years to suggest that fibrillation is a state of spatiotemporal chaos consisting of the perpetual nucleation and disintegration of spiral waves1,3, in association with a period doubling bifurcation of local electrical properties4–6. Nucleation of the initiating spiral wave pair is caused by local conduction block (wave break) secondary to spatial heterogeneity of refractoriness in the ventricle7–9. Until recently, spatial heterogeneity was thought to result solely from regional variations of intrinsic cellular electrical properties9,10 or from stimulation at more than one spatial location11,12. However, it is now appreciated that purely dynamical heterogeneity can be sufficient to cause conduction block during single site stimulation in both homogeneous one-dimensional models of canine heart tissue and in rapidly paced canine Purkinje fibers. A similar mechanism has been shown to precipitate conduction block and spiral break up in models of homogeneous two- and three-dimensional tissue11,14–17.

The period doubling bifurcation implicated in the transition to conduction block is manifest as alternans, a beat-to-beat long-short alternation in the duration of the cardiac action potential4–6,18,19. Previous investigators have hypothesized that alternans can be accounted for by a simple unidimensional return map called the action potential duration restitution function19. This hypothesis assumes the duration of an action potential (APD) depends only on its preceding diastolic interval (DI) through some function a(DI) that is measured experimentally. If the APD restitution function has a slope ≥ 1, then a period doubling bifurcation occurs for some value of the pacing cycle (BCL), where BCL = APD + DI. The velocity at which an action potential propagates (CV) also can be described by a restitution function, where CV = v(DI). More recently, other potential modulators of restitution, such as memory and calcium cycling, have been incorporated into formulations for restitution14,20–22.

Dynamically-induced spatial dispersion of repolarization

It has been shown previously that the combination of a steeply sloped APD restitution function and a monotonically increasing CV restitution function is sufficient to produce dynamical conduction block during sustained pacing at a short cycle length11,13. This observation may provide a generic mechanism for wave break and the onset of ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. However, it is unlikely that the conditions used to demonstrate this phenomenon experimentally apply to the clinical situation, where the induction of ventricular tachyarrhythmias typically is associated with the interruption of normal cardiac rhythm by only a few premature beats.

Recently, we determined whether dynamic heterogeneity and conduction block occur in a computer model of canine heart fibers in which pacing at a slow rate is interrupted by 1–4 premature stimuli23. This protocol simulates the interruption of sinus rhythm by 1–4 premature ventricular complexes, a situation that can lead to the onset of ventricular fibrillation clinically. Furthermore, we determined whether the conduction block induced in this way can be accounted for by the same dynamical mechanism that underlies the development of conduction block during rapid pacing. A coupled maps model of heart tissue was used for the study, which allowed us to identify the roles that CV and APD restitution play in the development of dynamic heterogeneity. We also considered the additional contribution of cardiac memory to the development of dynamical heterogeneity and conduction block.

These studies indicated that a short-long-short-short coupling interval pattern of premature stimuli induced marked spatial dispersion of repolarization and conduction block. The dynamical mechanism for the development of block was the same as for the development of discordant alternans during sustained rapid pacing. This type of conduction block could lead to wave break and spiral wave initiation if it occurred in two- and three-dimensional tissue, provided the block was local. The development of local block would be facilitated in intact myocardium by twist anisotropy and intrinsic heterogeneity.

Other researchers also have examined certain aspects of this problem. Watanabe et al.12 demonstrated that a single premature beat is sufficient to cause spatial heterogeneity in the form of discordant alternans, whereas Comtois et al.24 have demonstrated that two properly timed stimuli following the passage of a propagating wave can produce unidirectional block and spiral wave reentry with a large window of vulnerability. Qu et al.25,26 have conducted more extensive studies to determine how preexisting gradients in refractoriness interact with one or more premature stimuli to produce conduction block. However, general extension of these block mechanisms to two and three dimensions, their interaction with intrinsic and anatomical heterogeneity, their relationship to the development of wavebreak, in either simulation or experiment, have yet to be extensively explored.

A theory for the development of conduction block following premature stimulation

Recently, Otani developed a method that uses the APD and CV restitution relations to generate predictions regarding which sequences of premature stimuli are most likely to induce conduction block and reentry27. This method relies on the fact that when 1/vprevback > 1/v(DImin) at the stimulus site, block will occur for some finite range of the interval between the preceding and current stimuli. Here, vprevback is the velocity of the waveback of the preceding wave and v(DImin) is the conduction velocity when the preceding DI is the smallest value that allows propagation. Thus, block occurs when the trailing edge of the preceding wave travels slower than the leading edge of the current wave, allowing the latter to encroach and terminate on the former.

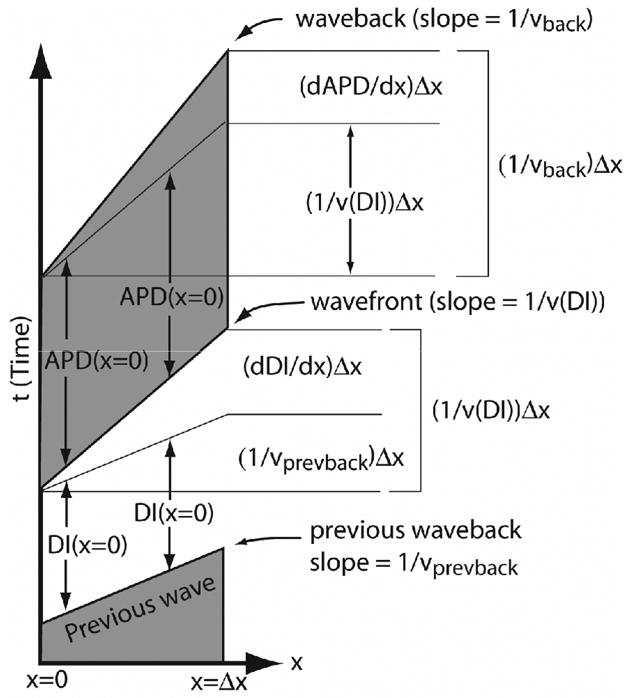

To determine when this blocking condition will be satisfied at the stimulus site, relationships are developed between the velocities of the wavefronts and wavebacks of all preceding waves. These relationships are most easily obtained by considering space-time plots of action potentials propagating in one spatial dimension. Wavefronts and wavebacks may be represented as diagonally oriented trajectories in this type of plot, as shown in Figure 1. The intervening grey and white regions then represent the action potentials and DIs, respectively. The slope of the wavefront trajectory in this representation is of the form, dt/dx and is therefore the inverse of the conduction velocity 1/v(DI). In general, the wavefront does not move with the same velocity as the waveback of the wave it is following; thus the intervening DI has a spatial gradient that, from the lower portion of Figure 1, is the difference between the wavefront and previous waveback inverse slopes:

Figure 1.

Graphical derivation of Eqs. (1) and (2) in x-t space for a short segment of tissue of length Δx. Stimuli are launched from x = 0. The lower portion of the figure shows dDI/dx as the difference in slopes between the inverse wavefront velocity, 1/v(DI)) and the inverse of the previous waveback velocity, 1/vprevback. The upper part of the figure shows dAPD/dx as the difference between the waveback and wavefront velocities, 1/vback and 1/v(DI).

| (1) |

where vprevback is the waveback velocity of the previous wave. Similarly, the waveback and wavefront of the same wave also do not typically travel with the same velocity. In this case, it is the spatial gradient in APD that creates the difference. Thus, as suggested by upper portion of Fig. 1, this gradient is given by,

| (2) |

where v(DI) and vback are the wavefront and waveback velocities of the same wave. Finally, the gradient in APD is related to the gradient in the previous DI through the chain rule:

| (3) |

where a′(DI) is the slope of the APD restitution function. We can now evaluate the blocking condition,

| (4) |

by repeatedly substituting equations (1–3) into Eq. (4).

Consider, for example, the case in which a series of action potential waves (S1) has settled down to constant CV, APD and DI following a period of slow, constant pacing, and then four premature stimuli (S2 through S5) are applied with diastolic intervals DIS2 through DIS5. By evaluating the condition (4) for this case, the S5 wave will block on the trailing edge of the S4 wave when

| (5) |

is greater than 0.

The form of this equation provides valuable information about the factors that produce block. The first term on the right-hand side tends to be negative, since the CV at the critical diastolic interval, DImin, tends to be smaller than velocities at large DIs. (This is always the case if the CV is not supernormal.) This term can be very negative if conduction is very slow at DImin. Thus, block is less likely if the conduction slows substantially when a wavefront approaches the waveback of the wave ahead of it. In addition, for block to occur, the remaining terms on the right-hand side must be positive enough to offset this first term. These remaining terms all have the same form—they are all sign-sensitive differences in inverse velocities of pairs of consecutive waves multiplied by slopes of the APD restitution function.

This relationship between CV and APD restitution allows us to make additional observations. First, differences in the launch velocities of consecutive waves tend to promote or inhibit, depending on the sign, the block of subsequently launched action potentials. Second, these tendencies are either amplified or suppressed, when the slope of the APD restitution function, a′(DI), is, respectively, greater or less than 1 for the DI of each premature wave launched. The slope need not necessarily be greater than 1 for block to occur; however, the factors that create block do tend to be enhanced or diminished, depending on the value of the slope relative to 1.

Canine model of sudden cardiac death

An attractive experimental model for testing the hypothesis that maximizing dynamically-induced spatial heterogeneity of repolarization is conducive to the development of VF is the inherited sudden death model developed by Moïse and co-workers28. This model consists of a colony of German shepherd dogs that are afflicted with an inherited propensity for sudden death. Affected dogs have frequent ventricular arrhythmias (VA), with those exhibiting ventricular tachycardia (VT) having the highest incidence of sudden death28. As determined by ambulatory Holter analysis, affected dogs can have up to 50,000 ventricular premature beats and runs of rapid VT during a 24 hr recording period.

Two types of VT have been identified; (1) a rapid (heart rate > 300 bpm), nonsustained, polymorphic form, and (2) a less rapid (heart rates < 250 bpm), sustained, monomorphic form28,29. The first type (85% of VT identified) is associated with sudden death and is frequently preceded by a pause. Moreover, this type of VT is most frequent during slow wave sleep, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and between 4 and 7 am. The average incidence of sudden death in affected dogs is approximately 33%. The reason why the remainder of these dogs do not develop VF, despite the presence of many episodes of rapid, polymorphic VT is unknown.

Important alterations in the ionic currents responsible for repolarization are present in these dogs29–31, including a decreased transient outward potassium current (Ito) and circumstantial evidence for decreased repolarization reserve. A reduction in outward repolarizing current presumably is responsible for the prolongation of action potential duration and development of prominent early afterdepolarizations (EADs) in left ventricular Purkinje fibers of affected dogs32. The EADs are the likely cause for the initiation of the pause dependent rapid polymorphic VT, the suspected initiator of VF. Abnormal T waves are seen on the surface ECG and are a reflection of the afterdepolarizations or the spatial inhomogeneity of repolarization among different regions of the left ventricle of affected dogs33. The latter could provide a permissive substrate for reentry arrhythmias as well.

Thus, the German shepherd model provides an opportunity to determine whether certain patterns of multiple premature beats (secondary to EAD-induced triggered activity) are sufficient to induce VF in the setting of significant intrinsic heterogeneity of repolarization. We have begun to investigate whether patterns of premature stimuli designed to maximize spatial dispersion of repolarization via augmentation of dynamic heterogeneity initiate VF in these animals. Moreover, we also are testing whether the spontaneously occurring VT cycle lengths in these animals typically do not induce VF because they do not augment dynamically-induced spatial dispersion of repolarization sufficiently.

As an initial test of this idea, five affected German shepherd dogs were studied in the closed chest anesthetized state. Dynamics restitution relations were determined from MAP recordings in the right and left ventricles and these data were fed into the mathematical condition described above to establish a relative risk for the induction of conduction block using various sequences of four premature stimuli. The preliminary results indicate that those sequences of premature cycle lengths that were predicted to induce conduction block by the mathematical algorithm were also the most likely to induce VF in the intact heart, whereas those sequences that were not predicted to precipitate conduction block did not cause VF. Further studies currently are in progress based on these encouraging results.

Future Directions

The results of these studies need to be interpreted in light of the realization that cellular electrical dynamics is unlikely to be predicted with absolute fidelity by simple models and that provocative tests that yield useful information in one setting may not necessarily be useful in a different setting. Programmed stimulation to identify patients at risk for sudden death and to evaluate the efficacy of therapy to prevent sudden death has, of course, been tried previously, with very disappointing outcomes34. The mode of programmed stimulation used in CAST was designed primarily to probe intrinsic heterogeneity of refractoriness. In contrast, our approach is designed to provoke and to evaluate dynamical heterogeneity, alone or superimposed on intrinsic heterogeneity. It seems likely that although our preliminary experiments indicate that patterns of stimulation based solely on dynamical heterogeneity reliably induce VF, intrinsic heterogeneity may need to be considered more fully in order for useful predictions to be generated for diseased myocardium.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported in part by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association, Northeast Affiliate (ARG) and by NIH grants HL075515, HL077938 and HL073644 (RFG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gray RA, Pertsov AM, Jalife J. Spatial and temporal organization during cardiac fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:75–8. doi: 10.1038/32164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss JN, Chen PS, Qu Z, Karagueuzian HS, Lin SF, Garfinkel A. Electrical restitution and cardiac fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:292–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witkowski FX, Leon LJ, Penkoske PA, Giles WR, Spano ML, Ditto WL, Winfree AT. Spatiotemporal evolution of ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:78–82. doi: 10.1038/32170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfinkel A, Kim YH, Voroshilovsky O, Qu Z, Kil JR, Lee MH, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN, Chen PS. Preventing ventricular fibrillation by flattening cardiac restitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6061–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090492697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmour RF, Jr, Chialvo DR. Electrical restitution, critical mass, and the riddle of fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1087–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karma A. Electrical alternans and spiral wave breakup in cardiac tissue. Chaos. 1994;4:461–472. doi: 10.1063/1.166024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arce H, Xu AX, Gonzalez H, Guevara MR. Alternans and higher-order rhythms in an ionic model of a sheet of ischemic ventricular muscle. Chaos. 2000;10:411–426. doi: 10.1063/1.166508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen PS, Wolf PD, Dixon EG, Danieley ND, Frazier DW, Smith WM, Ideker RE. Mechanism of ventricular vulnerability to single premature stimuli in open-chest dogs. Circ Res. 1988;62:1191–209. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.6.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson KJ, Henriquez C. Simulation and prediction of functional block in the presence of structural and ionic heterogeneity. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H2597–H2603. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan GX, Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Characteristics and distribution of M cells in arterially perfused canine left ventricular wedge preparations. Circulation. 1998;98:1921–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Chen PS, Weiss JN. Mechanisms of discordant alternans and induction of reentry in simulated cardiac tissue. Circulation. 2000;102:1664–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.14.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe MA, Fenton FH, Evans SJ, Hastings HM, Karma A. Mechanisms for discordant alternans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:196–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox JJ, Riccio ML, Hua F, Bodenschatz E, Gilmour RF., Jr Spatiotemporal transition to conduction block in canine ventricle. Circ Res. 2002;90:289–96. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenton FH, Cherry EM, Hastings HM, Evans SJ. Multiple mechanisms of spiral wave breakup in a model of cardiac electrical activity. Chaos. 2002;12:852–892. doi: 10.1063/1.1504242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrild D, Henriquez C. A computer model of normal conduction in the human atria. Circ Res. 2000;87:E25–36. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rappel WJ. Filament instability and rotational tissue anisotropy: a numerical study using detailed cardiac models. Chaos. 2001;11:71–80. doi: 10.1063/1.1338128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panfilov AV. Three-dimensional organization of electrical turbulence in the heart. Phys Rev E. 1999;59:R6251–R6254. doi: 10.1103/physreve.59.r6251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guevara MR. Electrical alternans and period doubling bifurcations. IEEE Comp Cardiol. 1984;562:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolasco JB, Dahlen RW. A graphic method for the study of alternation in cardiac action potentials. J Appl Physiol. 1968;25:191–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox JJ, Bodenschatz E, Gilmour RF., Jr Period-doubling instability and memory in cardiac tissue. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:138101–4. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolkacheva EG, Schaeffer DG, Gauthier DJ, Krassowska W. Condition for alternans and stability of the 1:1 response pattern in a “memory” model of paced cardiac dynamics. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;67:031904. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.031904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldhaber JI, Motter C, Duong TK, Weiss JN. Cellular basis of action potential duration alternans: Role of the L-type calcium current and intracellular calcium cycling. Circulation. 2002;106:228–228. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox JJ, Riccio ML, Drury P, Werthman A, Gilmour RF., Jr Dynamic mechanism for conduction block in heart tissue. New J Phys. 2003;5:101.1–101.14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comtois P, Vinet A, Nattel S. Wave block formation in homogeneous excitable media following premature excitations: Dependence on restitution relations. Phys Rev E. 2005;72:031919. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.031919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. Vulnerable window for conduction block in a one-dimensional cable of cardiac cells, 1: Single extrasystoles. Biophys J. 2006;91:793–804. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. Vulnerable window for conduction block in a one-dimensional cable of cardiac cells, 2: Multiple extrasystoles. Biophys J. 2006;91:805–815. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otani NF. Theory of action potential wave block at-a-distance in the heart. Phys Rev E. 2007;75:021910. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.021910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moise NS, Meyers-Wallen V, Flahive WJ, Valentine BA, Scarlett JM, Brown CA, Chavkin MJ, Dugger DA, Renaud-Farrell S, Kornreich B, et al. Inherited ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in German shepherd dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:233–43. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sosunov EA, Anyukhovsky EP, Hara M, Steinberg SF, Danilo R, Jr, Rosen MR, Moise NS, Merot J, Probst V, Charpentier F, Legeay Y, LeMarec H. Abnormal cardiac repolarization and impulse initiation in German shepherd dogs with inherited ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freeman LC, Pacioretty LM, Moise NS, Kass RS, Gilmour RF., Jr Decreased density of Ito in left ventricular myocytes from German shepherd dogs with inherited arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1997;8:872–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merot J, Probst V, Debailleul M, Gerlacin U, Moïse NS, LaMarec H, Charpentier F. Electropharmacological characterization of cardiac repolarization in German shepherd dogs with an inherited syndrome of sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:939–947. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilmour RF, Jr, Moise NS. Triggered activity as a mechanism for inherited ventricular arrhythmias in German shepherd Dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1526–33. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riccio ML, Moise NS, Otani NF, Belina JC, Gelzer ARM, Gilmour RF. Vector quantization of T wave abnormalities associated with a predisposition to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Ann Noninvas Electrocardiol. 1998;3:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, Peters RW, Obias-Manno D, Barker AH, Arensberg D, Baker A, Friedman L, Greene HL, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:781–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]