Abstract

Pleckstrin homology (PH) domains are sequences of ∼100 amino acids that form “modules” that have been proposed to facilitate protein/protein or protein/lipid interactions. Pleckstrin, first described as a substrate for protein kinase C in platelets and leukocytes, is composed of two PH domains, one at each end of the molecule, flanking an intervening sequence of 147 residues. Evidence is accumulating to support the hypothesis that PH domains are structural motifs that target molecules to membranes, perhaps through interactions with Gβγ or phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), two putative PH domain ligands. In the present studies, we show that pleckstrin associates with membranes in human platelets. We further demonstrate that, in transfected Cos-1 cells, pleckstrin associates with peripheral membrane ruffles and dorsal membrane projections. This association depends on phosphorylation of pleckstrin and requires the presence of its NH2-terminal, but not its COOH-terminal, PH domain. Moreover, PH domains from other molecules cannot effectively substitute for pleckstrin's NH2terminal PH domain in directing membrane localization. Lastly, we show that wild-type pleckstrin actually promotes the formation of membrane projections from the dorsal surface of transfected cells, and that this morphologic change is similarly PH domain dependent. Since we have shown previously that pleckstrin-mediated inhibition of PIP2 metabolism by phospholipase C or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase also requires pleckstrin phosphorylation and an intact NH2-terminal PH domain, these results suggest that: (a) pleckstrin's NH2terminal PH domain may regulate pleckstrin's activity by targeting it to specific areas within the cell membrane; and (b) pleckstrin may affect membrane structure, perhaps via interactions with PIP2 and/or other membrane-bound ligands.

Signal transduction pathways frequently use proteins that contain discrete domains that can facilitate intermolecular interactions. Well-characterized examples of such protein “modules” include the Src homology 2 and phosphotyrosine binding domains, which target phosphorylated tyrosine residues (21, 40), and Src homology 3 domains, which bind polyproline sequences, (21, 36). Pleckstrin homology (PH)1 domains, first described as 100– amino acid sequences found at the amino and carboxyl termini of the hematopoietic protein, pleckstrin, have been proposed as a new class of functional domains. The structures of PH domains from dynamin, spectrin, phospholipase C δ1 (PLCδ1), and the NH2 terminus of pleckstrin have been determined and are virtually superimposable, giving credence to their inclusion as a genuine family of structural motifs, despite significant divergence in their primary sequences (6–8, 11, 27, 37, 46). The molecular targets with which PH domains interact have not yet been clearly elucidated. PH domains have been suggested to bind to inositol phosphates (13), and the structures of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate complexed to the PH domains from spectrin and PLCδ1 have been recently reported (8, 18). The βγ subunits from heterotrimeric G proteins (Gβγ) have also been proposed as binding partners for PH domains (28, 39, 42), and we, along with others, have shown that PH domains from a number of different proteins can interact with Gβγ (4, 22, 33, 34, 38).

Pleckstrin is a 40-kD protein found solely in cells of hematopoietic origin and was first described as a major substrate for protein kinase C in human platelets (15). When expressed in Cos-1 cells, pleckstrin can inhibit phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis initiated by both G protein–coupled and growth factor receptors (1). This effect is dependent on the presence of an intact PH domain at the amino terminus of pleckstrin and can be regulated by phosphorylation of the molecule (2). Recombinant phospho-pleckstrin can also inhibit Gβγ-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) activity in human platelets (3). These data suggest a role for pleckstrin in the inhibition of cellular pathways involving PIP2 and/or Gβγ.

More than 100 proteins have been reported to contain PH domains. Among these are signaling molecules such as Ras-GAP, Ras-GRF, Sos, β-adrenergic receptor kinase (βARK), phospholipase C, insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1 and 2), and structural molecules, including spectrin and dynamin (12, 16, 29, 30, 35). Common to many of these proteins is a functional requirement for membrane localization, but there is a lack of traditional membraneanchoring groups such as lipophilic helices or sites for posttranslational addition of lipid moieties. Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that PH domains serve as membrane-targeting motifs. First, βARK must be located near the cell membrane in order for it to become activated and phosphorylate its receptor substrate. Deletion of a region overlapping the PH domain of βARK diminishes its kinase activity, and replacing this sequence with an isoprenylation site restores function to the molecule (22, 33). Second, the transforming ability of the Lfc protein requires an intact PH domain, and an isoprenylation site can effectively substitute for the PH domain in this activity (45). Third, IRS-1 mutants truncated of their PH domains are less effective substrates of the transmembrane insulin receptor than is the wild-type IRS-1 molecule (31). Fourth, a point mutation found within the PH domain of Bruton's tyrosine kinase activates the enzyme and also causes increased membrane association (25). Fifth, the PH domain at the carboxy terminus of βG spectrin has been shown to interact with brain membranes and to target plasma membranes in vivo (41, 43), and, lastly, PLCδ1 was demonstrated to require a PH domain for association with the plasma membrane (32).

Expanding the hypothesis that PH domains direct membrane targeting, we show in this report that pleckstrin interacts with membranes in human platelets. We also demonstrate that pleckstrin associates with peripheral membrane ruffles and membrane projections at the dorsal surface of transfected Cos-1 cells. The localization appears to be regulated by pleckstrin's sites of phosphorylation and to require the presence of the native NH2-terminal PH domain, the same structural features that we have previously shown to be necessary for pleckstrin's inhibition of PIP2 metabolism. Moreover, pleckstrin also appears to promote the formation of membranous projections from the dorsal surface of transfected cells, thus suggesting a new role for pleckstrin in mediating morphologic changes at the cell membrane.

Materials and Methods

Platelet Fractionation

Human platelets from normal volunteers were isolated by differential centrifugation of whole blood anticoagulated with acidified citrate dextrose (85 mM sodium citrate, 11 mM dextrose, 71 mM citric acid). Platelets were washed in Hepes/Tyrode buffer (129 mM NaCl, 8.9 mM NaHCO3, 2.8 mM KCl, 0.8 mM KH2PO4, 56 mM dextrose, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.8 mM MgCl2) with 1 μM prostaglandin E1, resuspended in ice-cold 30 mM KCl, 5 mM Pipes, pH 6.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM vanadate, 0.2% aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and then lysed by nitrogen cavitation. The lysate was spun first at 500 g for 15 min to remove intact cells. The supernatant from this low speed spin was then spun at 100,000 g for 60 min, and the high speed membrane pellet was separated from the supernatant. The high speed pellet was then extracted with 1% Triton X-100 in 30 mM KCl, 5 mM Pipes, pH 6.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM PMSF, 2 mM vanadate, 0.2% aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and then spun again at 100,000 g for 30 min. The Triton-soluble supernatant was separated from the Triton-insoluble pellet. Protein concentrations in each sample were determined using a bicinchoninic microassay kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), and 50 μg of protein from each sample was run on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were then probed with either rabbit anti–pleckstrin antisera or an antibody to the well-described membrane-bound protein, Gqα (44).

Lactate dehydrogenase activity assays, used to demonstrate that cytoplasmic contents were not trapped in the membrane fraction, were performed as follows: 100 μg of protein, 0.17 mg of NADH, and 80 μg of pyruvate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) were simultaneously added to a cuvette containing 1 ml of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, and the absorbance at 342 Å was measured every 15 s.

Construction of Pleckstrin Expression Vectors

The generation of expression plasmids encoding full-length human pleckstrin, the NH2-terminal PH deletion variant (Δ6-99), and pleckstrin variants containing mutations at Ser113, Thr114, and Ser117 has been described previously (1, 2). A vector encoding a COOH-terminal PH domain deletion variant (Δ246-345) with the hemagglutinin antigen epitope tag fused to the carboxy terminus of the molecule was generated by PCR overlap extension according to the technique of Ho et al. (17). The hemagglutinin antigen epitope tag was fused to the carboxy terminus of wild-type pleckstrin and the other pleckstrin variants using PCR mutagenesis. A variant deleted of both PH domains was constructed using a unique Pst site found within the region between the two PH domains. Chimeric variants of pleckstrin with the NH2-terminal PH domain replaced by the PH domain from either βARK or dynamin were generated by PCR overlap extension (17). A variant of pleckstrin in which two lysine residues (K13 and K14) were mutated to asparagines was constructed by PCR mutagenesis, using the technique of Landt et al. (23). The DNA sequences of all clones were confirmed and inserted into pCMV5.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfections

Cos-1 cells (American Type Cell Culture, Rockville, MD) were grown in DME with 10% FBS (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO BRL) under 5.5% CO2. Plasmid DNA coprecipitated with calcium phosphate was layered on Cos-1 cells for 24 h before cells were shocked with 10% glycerol for 2 min. Cells were washed three times with DME, trypsinized (GIBCO BRL), and then replated onto two-well chamber slides (Nunc, Naperville, IL) in preparation for immunostaining.

Antibody Preparation

Rabbit polyclonal antiserum (No. 354) was raised against a recombinant protein corresponding to pleckstrin residues Glu104-Asp233. Murine ascites from hybridoma cells expressing the mAb 12CA5 against the hemagglutinin antigen were purified on a protein A column (Affi-Gel; Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), concentrated to 1.57 mg/ml, and stored at 4°C. The anti-Gqα antiserum was kindly supplied by Dr. David Manning (Department of Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia).

Indirect Immunofluorescence

48 h after transient transfection, slides were washed with PBS, and then fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde, 100 mM Pipes, pH 6.8, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 for 30 min. Three washes in 150 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, were performed to quench free aldehyde groups, followed by 10min permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Biosource Intl., Camarillo, CA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. 12CA5 antibody, prepared as above, was diluted 1:100 in 10% normal goat serum in PBS and applied to cells for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed in PBS, and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h in affinity-purified, FITC-labeled goat F(Ab)2 anti–mouse antisera (Biosource Intl.) diluted 1:200 in 10% normal goat serum in PBS. Slides were washed in PBS, and then mounted in Citifluor antifadant mounting material (University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom).

For fluorescent double labeling of the cell surface and intracellular pleckstrin, living transfected cells on chamber slides were washed with PBS at room temperature, cooled on ice for 3 min, and then externally labeled with TRITC-conjugated WGA (Sigma Chemical Co.). After washing in PBS, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained as before.

Two methods were used for image collection and analysis. Conventional fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Microphot-SA microscope and camera (Nikon Inc., Garden City, NJ). We also used the resources of the University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center Confocal Microscopy Core Facility. Confocal images were acquired from a 4D Upright microscope (TCS-Medical Products Co., Huntington Valley, PA) and processed on an IBM OS9 workstation (IBM Instruments, Inc., Danbury, CT), using Scanware software. Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed using a 3D software package provided to the Confocal Core on loan from Leica Inc. (Deerfield, IL). All light microscopic figures were shot with a ×40 objective.

In Vivo Phosphorylation Studies

48 h after transient transfection, cells were incubated for 4 h in phosphatefree DME, containing 0.25 mCi/ml of 32Pi. Cells were lysed in Frackleton buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF) with 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 0.1% aprotinin, and 25 μg/ml leupeptin. After cell lysis, pleckstrin and pleckstrin variants were immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 and run on a polyacrylamide gel. Counts on the dried gel were quantified using a phosphor imager (Molecular Diagnostics, Sunnyvale, CA) to determine the degree of phosphorylation of the different pleckstrin variants.

Results

Pleckstrin Associates with Membrane in Human Platelets

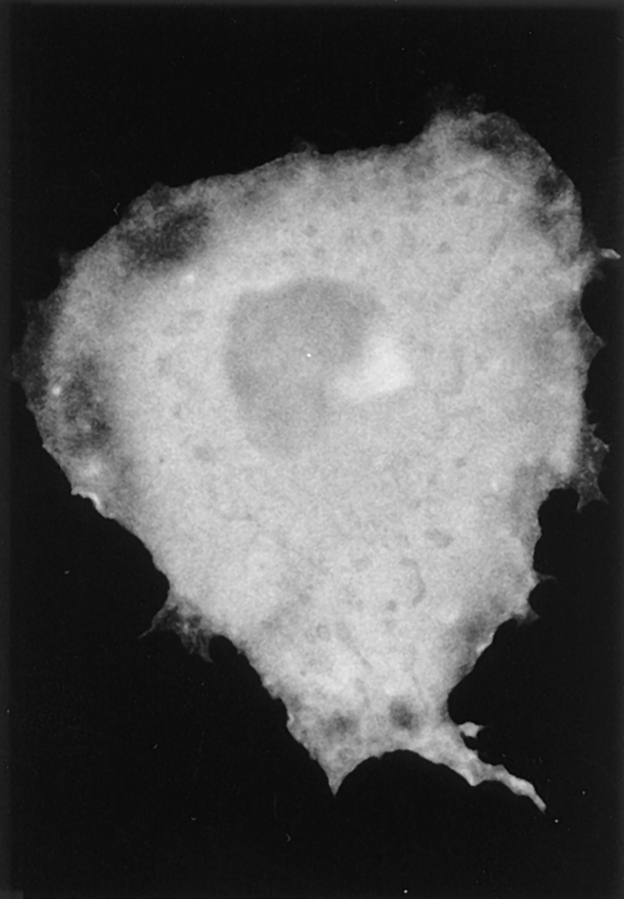

Pleckstrin is a major constituent of human platelets, comprising 0.65% of all platelet protein (26). To determine the subcellular localization of pleckstrin within human platelets, platelet lysates were spun at 100,000 g and separated into particulate and supernatant fractions. Equivalent amounts of protein were run on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with the anti-pleckstrin antisera. Though pleckstrin has previously been reported as a cytosolic platelet protein (19, 26), the anti-pleckstrin immunoblot shown in Fig. 1 A shows that pleckstrin can be detected in both the membrane pellet and the cytosolic supernatant of human platelets. When this pellet was extracted with 1% Triton X-100, the pleckstrin was found predominantly in the Triton-soluble fraction, consistent with membrane association (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1.

Localization of pleckstrin to membranes. (a) Antipleckstrin immunoblot of membrane pellet (lane 1) and cytosolic supernatant (lane 2) fractions from nitrogen-cavitated human platelets showing that a fraction of cellular pleckstrin is found in the membrane pellet. (b) As a control, an identical immunoblot probed with antisera against the α subunit if G protein, Gq, showing that Gq-α is found only in the membrane pellet (lane 1) and not in the supernatant fraction (lane 2). These blots are from an experiment representative of seven performed to date. (c) Antipleckstrin immunoblots of the Triton-soluble (lane 1) and -insoluble (lane 2) fractions of the high speed pellet from A are shown. Pleckstrin is found predominantly in the Triton-soluble fraction, consistent with membrane localization.

To demonstrate that the supernatant fraction did not contain membrane components, we performed immunoblotting with antisera to the membrane-associated protein, Gqα (44), and showed that this protein was not found in the supernatant fraction (Fig. 1 A). Similarly, the absence of lactate dehydrogenase activity in the pellet fraction argues that it was not contaminated with cytosolic components (data not shown).

Pleckstrin Associates with Peripheral Membrane Ruffles and Dorsal Membrane Projections in Transfected Cos-1 Cells

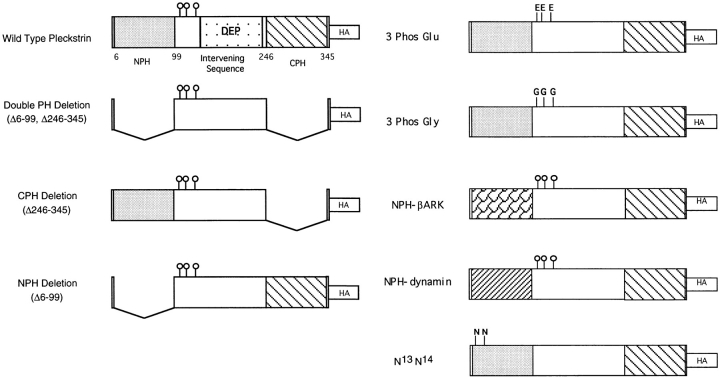

Having determined that pleckstrin associates with platelet membranes, we next sought to identify the regions of pleckstrin required for this interaction. To do this, we used indirect immunofluorescence to study the intracellular location of hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged wild-type and variant pleckstrins expressed in transfected Cos-1 cells. Fig. 2 shows schematic representations of the different pleckstrin variants used in this series of experiments. The attachment of the HA tag has been shown to have no effect on the ability of the pleckstrin variants to inhibit PLC activity (Abrams, C., unpublished observation).

Figure 2.

Pleckstrin variants. Wild-type pleckstrin and pleckstrin variants were tagged with the hemagglutinin epitope (HA) recognized by the mAb 12CA5 (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN).

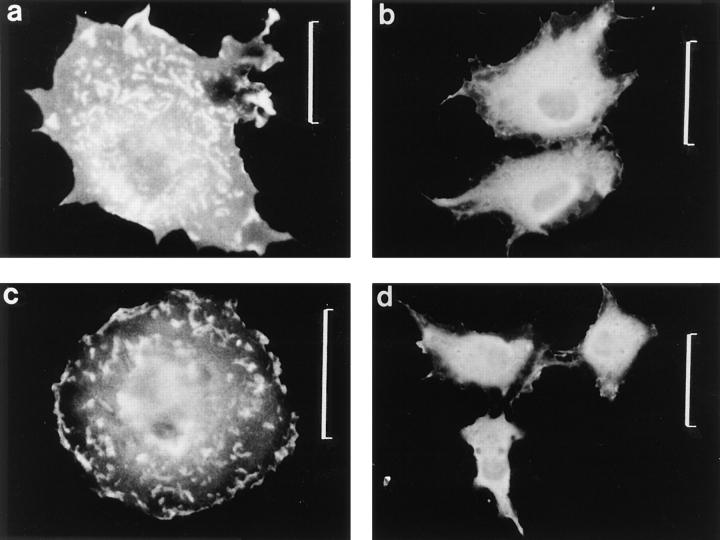

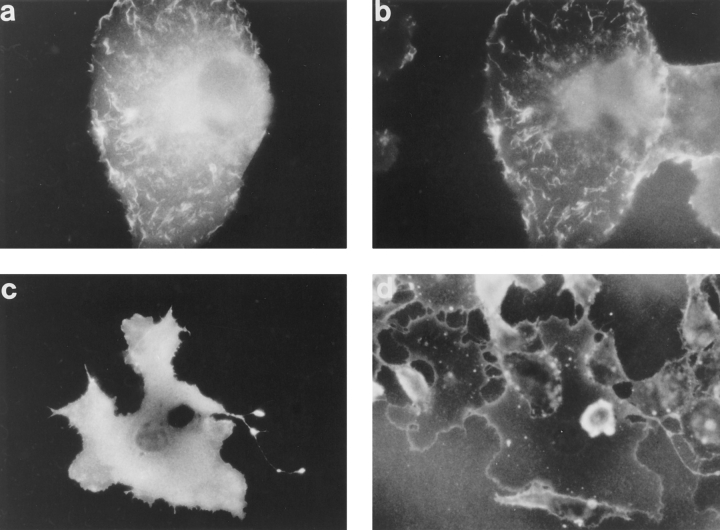

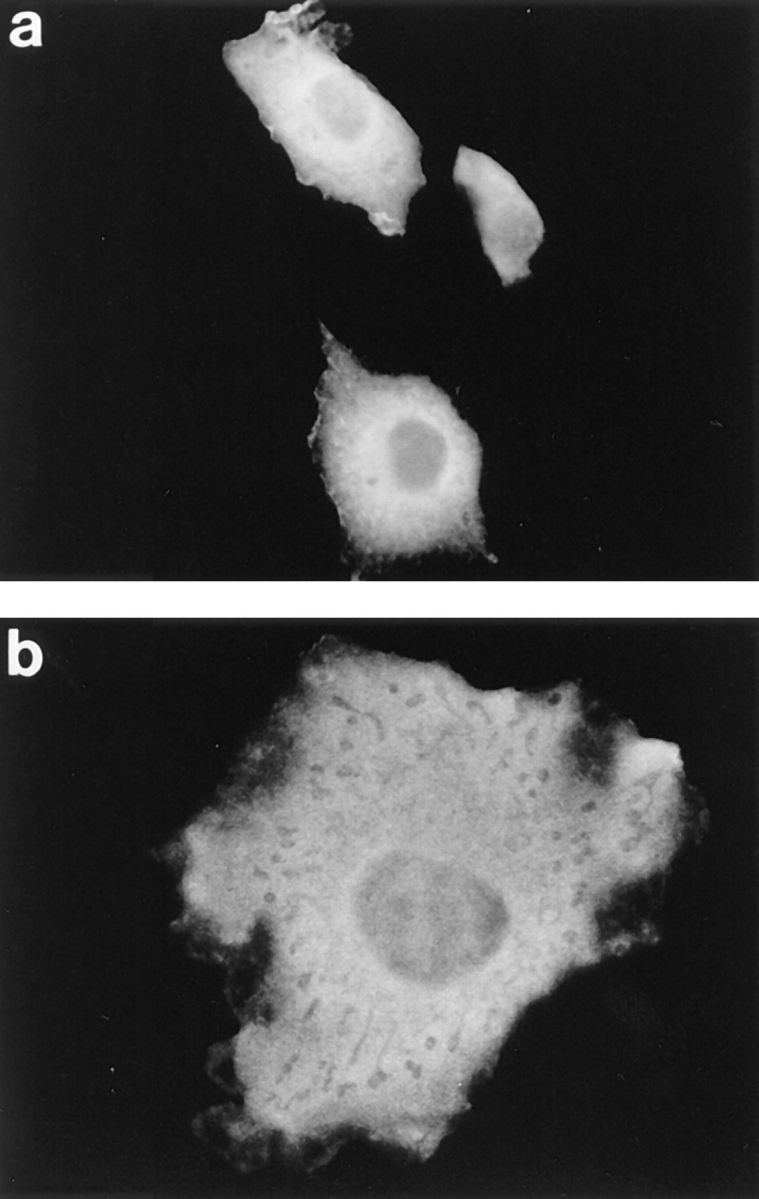

Expressed wild-type pleckstrin was found diffusely throughout the cytoplasm but concentrated most intensely around the plasma membrane, where it associated with areas of membrane folding or ruffles along the periphery of the cell (Fig. 3 a). In general, cells expressing wild-type pleckstrin were flatter and broader than mock-transfected cells or untransfected cells. Notably, cells transfected with wild-type pleckstrin also demonstrated membranous projections from their dorsal surface, and pleckstrin was also concentrated within these structures (Fig. 3 a). Confocal microscopy with three-dimensional reconstruction of images confirmed that these regions of intense pleckstrin staining were projections from the surface of the cell, rather than intracytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 4 a).

Figure 3.

Effect of PH domain deletions on localization of pleckstrin. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on Cos-1 cells transiently transfected with HAtagged pleckstrin variants, using the 12CA5 mAb against the HA epitope. Wild-type pleckstrin (a) and COOHterminal PH-deleted pleckstrin (Δ246-345) (c) localize to peripheral ruffles and projections from dorsal surface of the cell. Double PH-deleted pleckstrin (Δ6-99, Δ246-345) (b) and NH2-terminal PHdeleted pleckstrin (Δ6-99) (d) are diffusely localized. This suggests that the NH2terminal PH domain but not the COOH-terminal PH domain is critical for pleckstrin's localization to membrane structures. Bar, 50 μm.

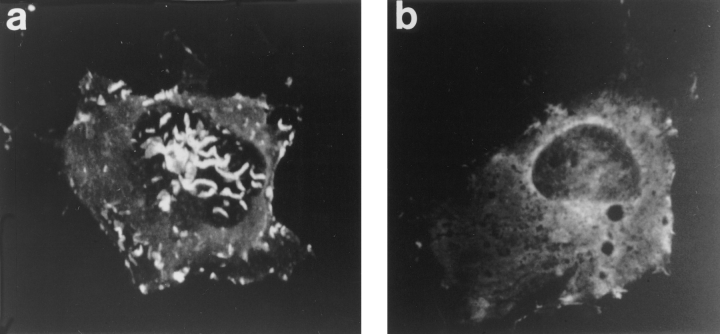

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy with three-dimensional image reconstruction was performed to better demonstrate membrane structures projecting from the dorsal surface of the cell. (a) Cells expressing wild-type pleckstrin exhibit bright staining within dorsal projections and peripheral ruffles. (b) Cells expressing double PH-deleted pleckstrin (Δ6-99, Δ246-345) exhibit diffuse staining. These images show that wild-type pleckstrin staining is not within intracytoplasmic structures, but rather within projections from the cell surface.

The NH2-terminal PH Domain Is Required for Membrane Localization

To determine whether pleckstrin was associating with membranes via its PH domains, Cos-1 cells were transfected with a variant of pleckstrin lacking both PH domains (Δ6-99, Δ246-345). Cells expressing this variant demonstrated a diffuse pattern of staining, consistent with loss of membrane interaction (Fig. 3 b). Unlike cells transfected with wild-type pleckstrin, cells expressing this variant were not broad and flattened, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles could be clearly seen. Moreover, no dorsal projections could be demonstrated by either light or confocal microscopy (Figs. 3 b and 4 b). To ascertain if these pleckstrininduced changes were related to the level of protein expression, we varied the concentration of plasmid used for transfections, and then analyzed cells expressing different levels of protein. The relative concentration of expressed protein was compared with anti-HA immunoblots of transfected cell lysates. Both the wild-type protein and the PH domain-truncation variant (Δ6-99, Δ246-345) migrated on an SDS polyacrylamide gel at their predicted molecular masses of 40 and 18 kD, respectively (data not shown). Though lower levels of expression of wild-type pleckstrin produced less peripheral staining and fewer dorsal projections, these structural features were still present, even when the expression of the wild-type protein was lower than that of the pleckstrin Δ6-99, Δ246-345 variant. Thus, the complete absence of peripheral staining and dorsal projections in cells expressing the pleckstrin variant missing its PH domains cannot be explained on the basis of levels of expression.

To examine the relative contribution from each of pleckstrin's two PH domains to its membrane localization, pleckstrin mutants individually deleted of either the NH2-terminal PH domain (Δ6-99) or the COOH-terminal PH domain (Δ246-345) were studied. Cells expressing the COOHterminal PH domain–deleted variant (Δ246-345) stained in a pattern indistinguishable from that of the wild-type molecule, (Fig. 3 c). As predicted by their amino acid sequences, these expressed proteins both migrated at 29 kD on SDS-PAGE as determined by immunoblotting with the anti-HA tag antibody, 12CA5. The cells were flat and showed peripheral staining and dorsal projections. In contrast, the NH2-terminal PH domain–deleted mutant (Δ699) was diffusely localized and had neither peripheral staining nor dorsal projections (Fig. 3 d). This suggests that the NH2-terminal PH domain, and not the COOHterminal PH domain, is critical in targeting pleckstrin to membranes and mediating morphologic changes.

Pleckstrin Must Be Phosphorylated to Associate with Membranes

Pretreating Cos-1 cells with 50 nM PMA affected neither the morphology of the cell nor the localization of expressed wild-type pleckstrin (data not shown). However, we have previously determined that, when overexpressed in Cos-1 cells, wild-type pleckstrin predominately exists in the phosphorylated state (2). Thus, it is still possible that phosphorylation regulates the ability of pleckstrin to associate with peripheral membranes and induce morphologic changes. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed two pleckstrin variants in which Ser113, Thr114, and Ser117, the residues normally phosphorylated by protein kinase C (2), were collectively mutated to either glutamates (3-phos glu) or to glycines (3-phos gly). We have previously shown that replacing the sites of phosphorylation with glutamate residues mimics the state of phosphorylation by introducing a cluster of negative charges in a region adjacent to the NH2-terminal PH domain. This variant was previously shown to be constitutively active in inhibiting PLC and PI3-K activity (2, 3). When this constitutively active pleckstrin variant was tested, it produced a phenotype and pattern of staining identical to that of the wild-type molecule (Figs. 3 a and 5 a).

The pleckstrin variant containing glycine substitutions at the sites of phosphorylation (3-phos gly) is relatively inactive biochemically when compared with the wild-type protein. For example, this mutant is much less efficient than wild-type pleckstrin at inhibiting PLC and PI3-K activity (2, 3). Cells expressing the 3-phos gly variant stained diffusely and were of the same size and shape as mocktransfected cells (Fig. 5 b). Immunolocalization of this variant in transfected Cos-1 cells produces a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern, similar to the variant truncated of its NH2-terminal PH domain (pleckstrin Δ6-99). This suggests that pleckstrin must be phosphorylated or contain charged residues in place of the sites of phosphorylation in order for it to bind to its target within the plasma membrane. This result may contrast with the finding that a fraction of cellular pleckstrin was associated with the cell membrane in unstimulated platelets. However, at this point we cannot exclude the possibility that these platelets were partially activated during our preparative process, thus resulting in pleckstrin phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

Effect of pleckstrin phosphorylation on intracellular localization. Cos-1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged variants of pleckstrin that had the residues normally phosphorylated by protein kinase C (Ser113, Thr114, Ser117) mutated to either glutamates (3-phos glu) or to glycines (3-phos gly). (a) The 3-phos glu variant produced the same pattern of staining as did the wild-type molecule, showing staining at the periphery and within dorsal projections. This variant has previously been shown to be constitutively active in mediating inhibition of PIP2 metabolism. (b) The 3-phos gly mutant, which cannot be phosphorylated, is diffusely localized and does not associate with membrane structures. This suggests that pleckstrin phosphorylation is critical for its effective recruitment to membranes.

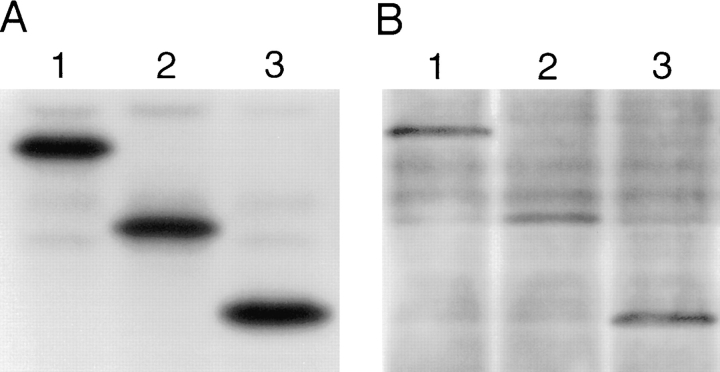

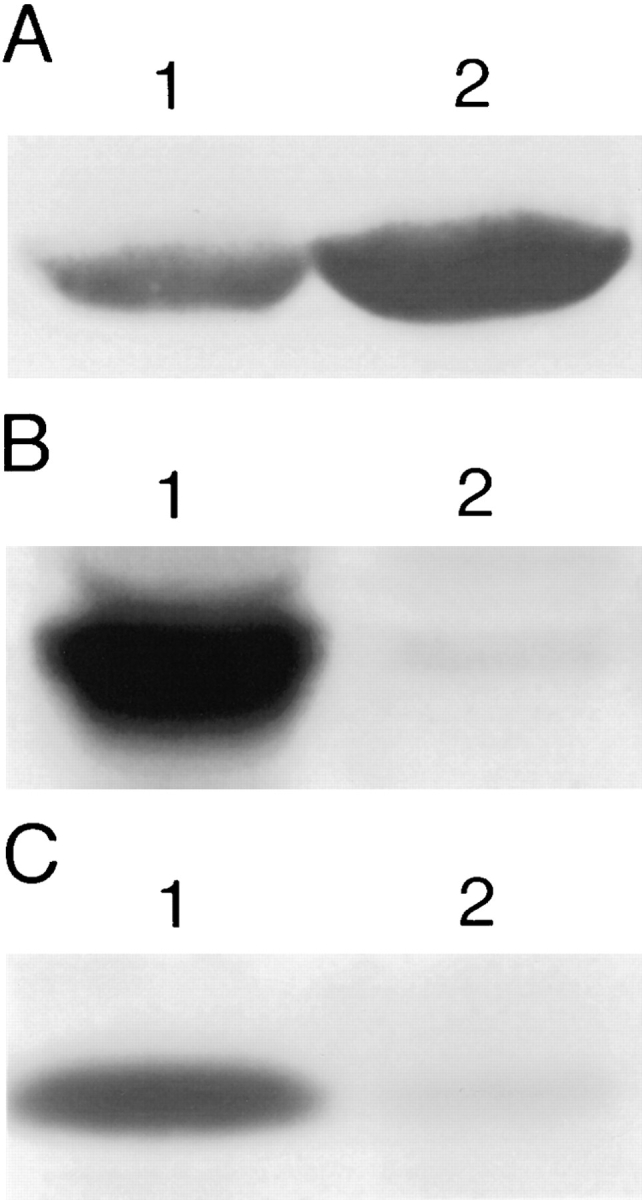

The requirement for pleckstrin to be phosphorylated to associate with Cos-1 cell membranes could be explained by two possible hypotheses: (a) the NH2-terminal PH domain, which is structurally regulated by pleckstrin phosphorylation, is critical for membrane association; or (b) pleckstrin phosphorylation, which is regulated by the NH2terminal PH domain, is required for membrane localization. To address this issue, we analyzed the state of phosphorylation of each of the expressed pleckstrin variants. Transfected Cos-1 cells were labeled with 32Pi, and the pleckstrin variants were immunoprecipitated and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. The relative radioactivity of each variant was compared by analysis on a phosphor imager. The wild-type pleckstrin and the pleckstrin variants missing either the NH2-terminal PH domain (Δ6-99) or the COOH-terminal PH domain (Δ246-345) were radiolabeled in vivo approximately equally (Fig. 6 A). Anti-pleckstrin immunoblots were performed in parallel to verify that each variant was expressed and immunoprecipitated equivalently (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

Effect of PH domain deletions on pleckstrin variant phosphorylation. Cos-1 cells were transfected with either wildtype pleckstrin or pleckstrin variants missing either the NH2-terminal PH domain (Δ6-99) (lane 2) or the COOH-terminal PH domain (Δ246-345) (lane 3). 48 h after transient transfection, cells were labeled with 32Pi, immunoprecipitated, and run on SDSPAGE gels. A shows that wild-type pleckstrin (lane 1) and the pleckstrin variants missing either the NH2-terminal PH domain (lane 2) or the COOH-terminal PH domain (lane 3) were phosphorylated equally. B shows an antipleckstrin immunoblot performed in parallel, demonstrating that these variants all expressed and immunoprecipitated equally well.

Thus, it is the NH2-terminal PH domain of pleckstrin that is critical for its association with the plasma membrane. The phosphorylation of pleckstrin appears to regulate this PH domain but does not, by itself, appear to be sufficient for membrane association.

Other PH Domains Cannot Substitute for Pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH Domain

Since the structures of PH domains from a number of different proteins are all remarkably similar, we determined if different PH domains could mediate membrane localization when substituted in place of pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain. Plasmids directing the expression of chimeric pleckstrin variants were constructed in which pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain was replaced by the PH domain from either βARK (NPH-βARK) or dynamin (NPH-dynamin). These two chimeras were expressed at their predicted molecular weight as judged by anti-HA immunoblots. Neither chimera behaved like wild-type pleckstrin. Cells expressing either of these molecules stained diffusely, had no dorsal projections, and were of normal size and shape (Fig. 7, a and b). This suggests that pleckstrin's native NH2-terminal PH domain makes specific interactions with ligands in the plasma membrane, and that, despite having similar structures, other PH domains cannot effectively substitute in these associations.

Figure 7.

Localization of pleckstrin NH2-terminal PH domain chimeras. Cos-1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged variants of pleckstrin in which the NH2-terminal PH domain had been replaced with either the PH domain of βARK (a) or dynamin (b). Neither chimera behaved like wild-type pleckstrin, suggesting that pleckstrin's native NH2-terminal PH domain is making specific interactions with membrane-bound ligands in which other PH domains, despite having striking structural similarities, cannot effectively substitute.

PIP2-binding Residues in the NH2-terminal PH Domain Are Necessary for Pleckstrin's Membrane Association

Fesik and co-workers mapped the sites of PIP2 interaction within the NH2-terminal PH domain of pleckstrin, based on 31P chemical shifts seen in PIP2 upon addition of the N2-terminal PH domain (14). A cluster of three lysine residues (K13, K14, and K22) was shown to be critical in mediating the association of pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain with PIP2. When any one of these residues was mutated to an asparagine, the affinity of the resultant molecule for PIP2 decreased 10-fold (14). Therefore, we generated a plasmid that directed the expression of a pleckstrin variant in which the first two of these lysines were mutated to asparagines (N13, N14) and tested this variant for its ability to associate with membranes. This pleckstrin variant also migrated at its predicted molecular weight on SDS polyacrylamide gels, and in vivo labeling studies demonstrated that its phosphorylation was approximately equal to that of the wild-type protein when overexpressed in Cos-1 cells (data not shown). Cells expressing this variant stained diffusely, had no dorsal projections, and were not broadened. This finding argues that interactions between pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain and PIP2 may be critical for its association with membranes (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of mutating PIP2-binding residues in NH2-terminal PH domain. Cos-1 cells were transiently transfected with a vector encoding the HA-tagged pleckstrin variant K13N, K14N, and then stained with 12CA5. This variant produced a diffuse pattern of staining, thus demonstrating that mutating two residues in pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain can disrupt the membrane association of the entire molecule. This suggests a critical role for interactions between PIP2 and pleckstrin's NH2-terminal PH domain in mediating recruitment of the molecule to the plasma membrane.

Pleckstrin Promotes the Formation of Membrane Projections from the Dorsal Surface of Transfected Cells

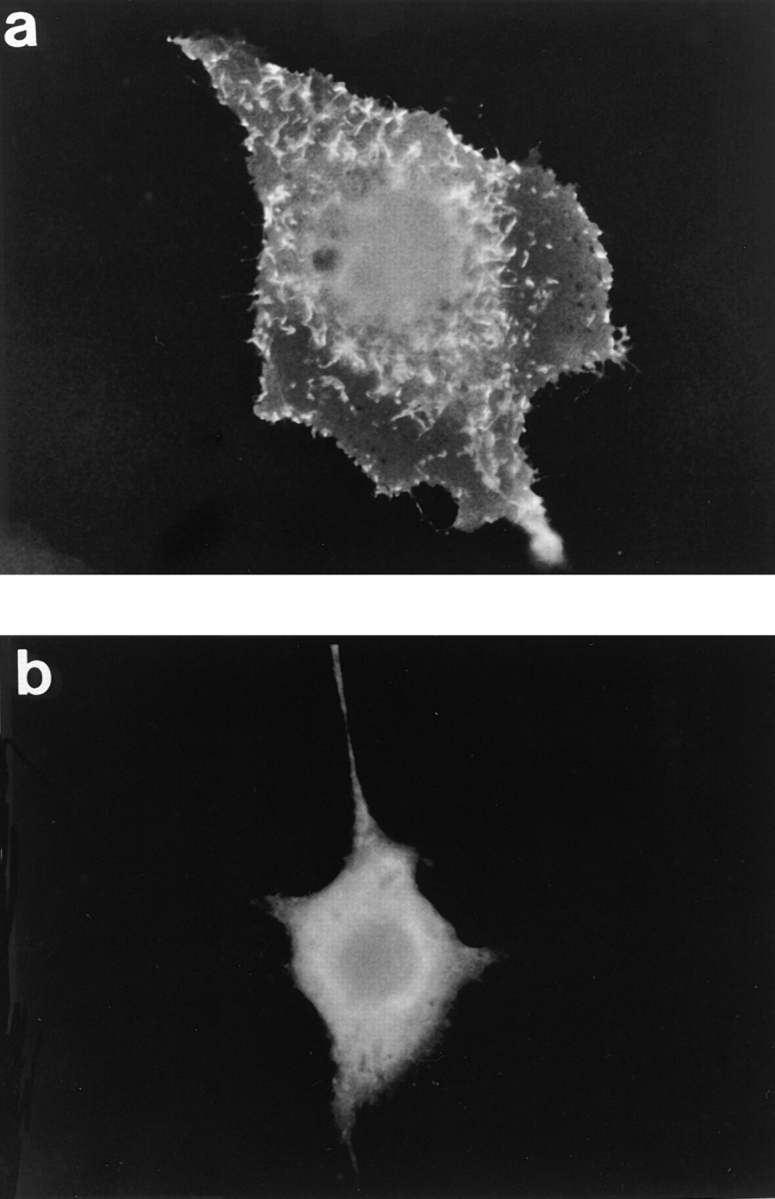

To determine if pleckstrin was inducing the formation of the dorsal villous projections or was merely being recruited to these membrane structures, we used fluorescently labeled WGA, which binds to cell surface glycoproteins and thus labels the surfaces of all cells, including cells not expressing pleckstrin. By fluorescently labeling the cell surface and then staining for expressed pleckstrin, we could study whether cells expressing pleckstrin differed in their surface morphology from those cells not expressing pleckstrin. Under these conditions, only cells expressing wild-type pleckstrin demonstrated surface projections (Fig. 9, a and b). This is in contrast to cells transfected with the pleckstrin variant missing its PH domains and nontransfected cells, which did not have dorsal projections (Fig. 9, c and d). This observation is consistent with pleckstrin actually inducing the formation of these membrane structures and changing cell surface architecture, in a fashion dependent on the presence of its PH domains.

Figure 9.

Effect of pleckstrin variants on cell surface morphology. Cells expressing either HA-tagged pleckstrin or the HA-tagged double PH-deleted pleckstrin (Δ6-99, Δ246-345) were surface labeled with TRITC-conjugated WGA, and then fixed and stained with 12CA5. Cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type pleckstrin are shown in a and b, and cells expressing the HA-tagged double PH-deleted pleckstrin variant are shown in c and d. a and c show 12CA5 staining for the HA epitope, and b and d show TRITC-conjugated WGA staining of the cell surface. Cells expressing wild-type pleckstrin exhibit projections from the dorsal surface of the cell (b), and pleckstrin is found within these projections (a). In contrast, cells expressing the double PH domain-deleted variant of pleckstrin exhibit diffuse pleckstrin staining (c) and fail to form dorsal projections (d). This suggests a new role for pleckstrin in mediating morphologic changes at the cell surface.

Discussion

Although the phosphorylation of pleckstrin has long been used as a marker for platelet activation, we are only now beginning to understand its intracellular role. Previous works have suggested that pleckstrin may: (a) inhibit the hydrolysis of PIP2 by multiple isoforms of PLC (1); (b) inhibit the phosphorylation of PIP2 by a Gβγ-activated isoform of PI3-K (3); and (c) activate an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate–specific 5′ inositol phosphatase (5). These activities are all regulated by phosphorylation of pleckstrin near its NH2-terminal PH domain (2, 3, 5). This present study builds on these findings and shows that pleckstrin associates with the plasma membrane and peripheral ruffles by a mechanism dependent on both pleckstrin phosphorylation and an intact NH2-terminal PH domain. In addition, we show that pleckstrin induces the formation and associates with dorsal membrane projections in transfected Cos-1 cells. These observations raise a number of questions, including the specificity of the PH domains in membrane targeting, the potential membranebound ligands for pleckstrin, and the significance of both the dorsal projections and pleckstrin's intracellular localization.

Since PH domains were first reported as components of signaling molecules other than pleckstrin itself, they have been proposed as structural motifs important in recruiting molecules to the plasma membrane. A preponderance of evidence now exists supporting this hypothesis (22, 25, 31– 33, 41, 45). However, even though the three-dimensional structures from different PH domains are strikingly similar in their backbone, there exist regions of marked primary and tertiary structural diversity (6–8, 11, 27, 37, 46). It stands to reason that these signaling modules may not be interchangeable between molecules. Consistent with this proposal, PH domains from different proteins have different binding affinities for inositol phosphates (13, 24), Gβγ (28), and brain membranes (41). Our results support the hypothesis that PH domains have different specificities for ligands within the membrane by demonstrating that pleckstrin can be recruited to membrane structures by its own NH2-terminal PH domain, but not by other PH domains.

The identity of the specific ligands targeted by PH domains remains unresolved. Several classes of molecules have now been proposed as potential PH domain ligands, including PIP2, Gβγ, and phosphotyrosine residues. The data showing that pleckstrin is able to inhibit PLCγ as well as PLCβ suggest a direct interaction between pleckstrin and PIP2. However, the observation that pleckstrin is able to inhibit only the Gβγ-activated isoform of PI3-K and not the isoforms of PI3-K activated by growth factor receptors suggests that Gβγ may as well be able to modulate pleckstrin's interaction with other ligands. The data presented here showing that targeted mutations of PIP2-binding residues within the NH2-terminal PH domain disrupt pleckstrin's membrane association support a role for PIP2 as a physiologic ligand for pleckstrin and its NH2-terminal PH domain. Additionally, our preliminary studies in Cos-1 cells reveal that overexpression of either wild-type or nonisoprenylated Gβγ heterodimers has no effect on pleckstrin's membrane localization.

The appearance of expressed pleckstrin within dorsal projections of transfected cells is intriguing, especially since pleckstrin variants lacking the NH2-terminal PH domain are not seen in these structures. Moreover, we have shown that pleckstrin, in a fashion dependent on its PH domains, is in fact inducing the formation of these projections. Interestingly, the appearance of these projections is reminiscent of the findings seen in CV-1 cells expressing the actin-binding protein, villin (9, 10). Since villin also binds PIP2 (20), it is tempting to speculate that pleckstrin may be causing the appearance of these villous projections in a PIP2-dependent manner. Determining whether pleckstrin is inducing the formation of these structures, and the other factors that may regulate this process, are areas of ongoing investigation in our laboratory.

It is striking that the structural regions within pleckstrin that regulate its ability to inhibit the accumulation of second messengers are the same regions that affect its intracellular localization. Both pleckstrin-mediated biochemical effects and the recruitment of pleckstrin to peripheral membranes require pleckstrin phosphorylation and an intact NH2-terminal PH domain. Control of the intracellular location of signaling molecules is a common method of regulating their function. An attractive hypothesis is that pleckstrin is recruited to the peripheral membrane upon cell activation by potential ligands such as PIP2 or Gβγ. We are actively investigating whether pleckstrin's activity is regulated by localization to the proximity of these biochemical targets.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health (HL07439-17, HL53545, and HL54500) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (95014910). C.S. Abrams is a recipient of an AHA-Sanofi Winthrop Award.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- βARK

β–adrenergic receptor kinase

- Gβγ

βγ

- subunit of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins; HA

hemagglutinin

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PI3-K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PLC

phospholipase C

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Dr. Charles S. Abrams, Hematology- Oncology Division, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 422 Curie Blvd., Stellar-Chance Labs #1005, Philadelphia, PA 19104. Tel.: (215) 898-1058. Fax: (215) 662-7617. e-mail: abramsc@mail.med.upenn.edu

References

- 1.Abrams CS, Wu H, Zhao W, Belmonte E, White D, Brass LF. Pleckstrin inhibits phosphoinositide hydrolysis initiated by G-protein coupled receptors and growth factor receptors: a role for pleckstrin's PH domains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14485–14492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams CS, Zhao W, Belmonte E, Brass LF. Protein kinase C regulates pleckstrin by phosphorylation of sites adjacent to the N-terminal pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22317–22321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams CS, Zhang J, Downes CP, Tang X-w, Zhao W, Rittenhouse S. Phospho-pleckstrin inhibits Gβγ-activatible platelet phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate-3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25192–25197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams CS, Zhao W, Brass LF. A site of interaction between pleckstrin's PH domains and Gβγ . Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1314:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(96)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auethavekiat V, Abrams CS, Majerus PW. Binding and activation of inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase I by platelet pleckstrin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1786–1790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downing AK, Driscoll PC, Gout I, Salim K, Zvelebil MJ, Waterfield MD. Three-dimensional solution structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from dynamin. Curr Biol. 1994;4:884–891. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson K, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Sigler PB. Crystal structure at 2.2 Å resolution of the pleckstrin homology domain from human dynamin. Cell. 1994;79:199–209. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson KM, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Sigler PB. Structure of the high affinity complex of inositol trisphosphate with a phospholipase C pleckstrin homology domain. Cell. 1995;83:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franck Z, Footer M, Bretscher A. Microinjection of villin into cultured cells induces rapid and long-lasting changes in cell morphology but does not inhibit cytokinesis, cell motility, or membrane ruffling. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2475–2485. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friederich E, Huet C, Arpin M, Louvard D. Villin induces microvilli growth and actin redistribution in transfected fibroblasts. Cell. 1989;59:461–475. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fushman D, Cahill S, Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J, Cowburn D. Solution structure of pleckstrin homology domain of dynamin by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:816–820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson TJ, Hyvönen M, Musacchio A, Saraste M, Birney E. PH domain: the first anniversary. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:349–353. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harlan JE, Hajduk PJ, Yoon HS, Fesik SW. Pleckstrin homology domains bind to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature (Lond) 1994;269:168–170. doi: 10.1038/371168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harlan JE, Yoon HS, Hajduk PJ, Fesik SW. Structural characterization of the interaction between a pleckstrin homology domain and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9859–9864. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haslam RJ, Lynham JA, Fox JEB. Biochem J. 1979;178:397–406. doi: 10.1042/bj1780397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haslam RJ, Koide HB, Hemmings BA. Pleckstrin domain homology. Nature (Lond) 1993;363:309–310. doi: 10.1038/363309b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Sitedirected mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene (Amst) 1989;7:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyvönen M, Macias MJ, Nilges M, Oschkinat H, Saraste M, Wilmanns M. Structure of the binding site for inositol phosphates in a PH domain. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1995;14:4676–4685. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imaoka T, Lynham JA, Haslam RJ. Purification and characterization of the 47,000-dalton protein phosphorylated during degranulation of human platelets. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11404–11414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janmey PA, Lamb J, Allen PG, Matsudaira PT. Phosphoinositide-binding peptides derived from the sequences of gelsolin and villin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11818–11823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch CA, Anderson D, Moran MF, Ellis C, Pawson T. SH2 and SH3 domains: elements that control interactions of cytoplasmic signaling proteins. Science (Wash DC) 1991;252:668–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1708916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch WJ, Inglese J, Stone WC, Lefkowitz RJ. The binding site for the βγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins on the β-adrenergic receptor kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8256–8260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landt O, Grunert H-P, Hahn U. A general method for rapid site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene (Amst) 1990;96:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90351-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemmon MA, Ferguson KM, O'Brien R, Sigler PB, Schlessinger J. Specific and high-affinity binding of inositol phosphates to an isolated pleckstrin homology domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10472–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li T, Tsukada S, Satterthwaite A, Havlik MH, Park H, Takatsu K, Witte OW. Activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) by a point mutation in its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Immunity. 1995;2:451–460. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons RM, Atherton RM. Characterization of a platelet protein phosphorylated during the thrombin-induced release reaction. Biochemistry. 1979;18:544–552. doi: 10.1021/bi00570a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macias M, Musacchio A, Ponstingl H, Nilges M, Saraste M, Oschkinat H. Structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from β spectrin. Nature (Lond) 1994;369:675–677. doi: 10.1038/369675a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahadevan D, Thanki N, Singh J, McPhie P, Zangrilli D, Wang L-M, Guerrero C, LeVine H, Humblet C, Saldanha J, et al. Structural studies on the PH domains of Dbl, Sos1, IRS-1, βARK1 and their differential binding to Gβγsubunits. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9111–9117. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayer BJ, Ren R, Clark KL, Baltimore D. A putative modular domain present in diverse signalling proteins. Cell. 1993;73:629–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90244-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musacchio A, Gibson T, Rice P, Thompson J, Saraste M. The PH domain: a common piece in the structural patchwork of signalling proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:343. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90071-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers MGJ, Grammer TC, Brooks J, Glasheen EM, Wang L-M, Sun XJ, Blenis J, Pierce JH, White MF. The pleckstrin homology domain in insulin receptor substrate-1 sensitizes insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11715–11718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paterson HF, Savapoulos JW, Perisic O, Cheung R, Ellis MV, Williams RL, Katan M. Phospholipase Cδ1requires a pleckstrin homology domain for interaction with the plasma membrane. Biochem J. 1995;312:661–666. doi: 10.1042/bj3120661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitcher JA, Inglese J, Higgins JB, Arriza JL, Casey PJ, Kim C, Benovic JL, Kwatra MM, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Role of βγ subunits of G proteins in targeting the β-adrenergic receptor kinase to membrane-bound receptors. Science (Wash DC) 1995;257:1264–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1325672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitcher JA, Touhara K, Payne ES, Lefkowitz RJ. Pleckstrin homology domain-mediated membrane association and activation of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase requires coordinate interaction with Gβγsubunits and lipid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11707–11710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rebecchi M, Peterson A, McLaughlin S. Phosphoinositidespecific phospholipase C-δ1 binds with high affinity to phospholipid vesicles containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12742–12747. doi: 10.1021/bi00166a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren R, Mayer BJ, Cichetti P, Baltimore D. Identification of a ten-amino acid proline-rich SH3 binding site. Science (Wash DC) 1993;259:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.8438166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timm D, Salim K, Gout I, Guruprasad L, Waterfield M, Blundell T. Crystal structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from dynamin. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:782–788. doi: 10.1038/nsb1194-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Touhara K, Inglese J, Pitcher JA, Shaw G, Lefkowitz R. Binding of G protein βγ-subunits to pleckstrin homology domains. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10217–10220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukada S, Simon MI, Witte ON, Katz A. Binding of βγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins to the PH domain of Bruton tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11256–11260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Geer P, Pawson T. The PTB domain: a new protein module implicated in signal transduction. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D-S, Shaw G. The association of the C-terminal region of βIΣII spectrin to brain membranes is mediated by a PH domain, does not require membrane proteins, and coincides with an inositol-1,4,5 trisphosphate binding site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;217:608–615. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D-S, Shaw R, Winkelmann JC, Shaw G. Binding of PH domains of β-adrenergic receptor kinase and β-spectrin to WD40/βtransducin repeat containing regions of the β-subunit of heterotrimeric G-proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:29–35. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang D-S, Miller R, Shaw R, Shaw G. The pleckstrin homology domain of human β1ΣII spectrin is targeted to the plasma membrane in vivo. . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225:420–426. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wedegaertner PB, Chu DH, Wilson PT, Levis MJ, Bourne HR. Palmitoylation is required for signaling functions and membrane attachment of Gq alpha and Gs alpha. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25001–25008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitehead I, Kirk H, Tognon C, Trigo-Gonzales G, Kay R. Expression cloning of lfc, a novel oncogene with structural similarities to guanine nucleotide exchange factors and to the regulatory region of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18388–18395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon HS, Hajduk P, Petros AM, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Fesik SW. Solution structure of a pleckstrin homology domain. Nature (Lond) 1994;369:672–677. doi: 10.1038/369672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]