Abstract

The photosensitization of reactive oxygen species and, in particular, singlet oxygen by proteins from the green fluorescent protein (GFP) family influences important processes such as photobleaching and genetically targeted chromophore-assisted light inactivation. In this article, we report an investigation of singlet oxygen photoproduction by GFPs using time-resolved detection of the NIR phosphorescence of singlet oxygen at 1275 nm. We have detected singlet oxygen generated by enhanced (E)GFP, and measured a lifetime of 4 μs in deuterated solution. By comparison with the model compound of the EGFP fluorophore 4-hydroxybenzylidene-1,2-dimethylimidazoline (HBDI), our results confirm that the β-can of EGFP provides shielding of the fluorophore and reduces the production of this reactive oxygen species. In addition, our results yield new information about the triplet state of these proteins. The quantum yield for singlet oxygen photosensitization by the model chromophore HBDI is 0.004.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins from the family of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) have become popular as genetically encoded reporters for intracellular dynamics, protein expression, and protein-protein interaction studies based on fluorescence microscopy (1,2). However, extended observation of GFPs is limited by photobleaching/photoconversion of the chromophore or light-induced damage of the surrounding biological medium. Photoproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can play a role in this limitation (3). Photosensitized singlet oxygen (1O2) has indeed been detected in GFP-expressing Escherichia coli bacteria and kidney cells by means of electron spin resonance (4). 1O2 is a highly reactive ROS that is potentially damaging to biological systems. In proteins, damage is mainly directed to cysteine, histidine, methionine, and tryptophan residues (5). The photoinduced formation of 1O2 mainly involves energy transfer from a photosensitizer with a suitable triplet energy level. Although photooxidation by 1O2 is not the main photobleaching pathway in GFPs, its influence in the process has been evidenced (6).

Photosensitization of 1O2 by GFP-like proteins is not only regarded as a negative factor affecting its performance in fluorescence microscopy, but it can also be of great use in genetically targeted chromophore-assisted light inactivation (CALI) (7). CALI consists in the illumination of a photosensitizer-tagged molecule to specifically inactivate a target. It has been shown that it is possible to use GFP derivatives for this purpose (8–11). Moreover, GFPs have been mutated with the particular goal of generating ROS for photodestruction of cells. Very recently, Lukyanov et al. have developed KillerRed, a fully genetically encoded photosensitizer derived from the GFP-like hydrozoan chromoprotein anm2CP (12). Killer Red inactivates efficiently E. coli and eukaryotic cells, and it has been shown that 1O2 is the main responsible for its phototoxicity.

Despite the interest generated by the capability of GFPs to behave like photosensitizers (1,2), very few studies have addressed this topic. In this article, we report the investigation of 1O2 photosensitization by GFP-like proteins by means of time-resolved detection of the NIR phosphorescence of 1O2 at 1275 nm (13). We have chosen EGFP as model protein for this study, and we have compared the results with those on the model compound of the EGFP fluorophore 4-hydroxybenzylidene-1,2-dimethylimidazoline (HBDI) (14). This comparison may assist in the estimation of the effect of the protein scaffold on the photosensitization properties.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

HBDI was synthesized as described previously (purity >95%) (14). The EGFP vector was purchased from Clontech Laboratories (Mountain View, CA). The measurements were performed in D2O (SdS, Solvents Documentation Synthesis, Peypin, France) buffered solutions, since deuterium greatly enhances the 1O2 lifetime and thus makes its detection easier. Thus, all the HBDI experiments were carried out in D2O buffered solutions, while all the EGFP experiments were performed in a 1:3 mixture of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and deuterated PBS (D-PBS).

Ground-state absorption spectra were recorded using a 4E spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). For time-resolved phosphorescence detection, irradiation at 355 nm or 532 nm was achieved with a Q-switched diode-pumped Nd:YAG laser (10 kHz repetition rate, FTSS 355-Q; Crystal Laser Systems, Berlin, Germany), which produces ∼1 ns pulse-width laser pulses at 355 nm (5 mW, 0.5 μJ per pulse) or at 532 nm (12 mW, 1.2 μJ per pulse). NIR phosphorescence was detected using a customized time-correlated single-photon counting instrument (Fluotime 200, PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany) equipped with a NIR-sensitive photomultiplier (model No. H9179-45, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) and a multichannel scalar (model No. MSA300, Becker & Hickl, Berlin, Germany). The amount of laser pulses received by each sample (ranging from 20 to 40 millions) as well as the channel width (20–200 ns/channel) was changed from experiment to experiment.

HBDI samples were contained in squared 1-cm optical path fused silica cuvettes (model No. 101-QS, Hellma, Muellheim/Baden, Germany), whereas EGFP solutions were contained in rectangular 1 × 0.4 × 3.5 cm fused silica cuvettes (model No. QS-117.104F, Hellma), and were centrifuged before use. The concentration of the samples was adjusted to produce an absorbance at the excitation wavelength close to 0.1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

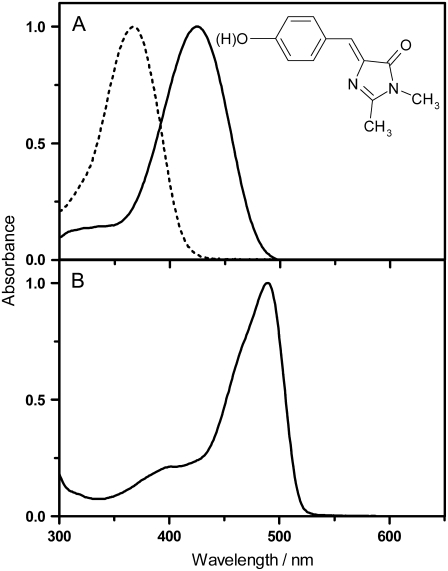

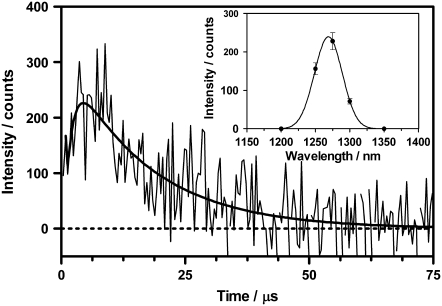

The absorption spectra of EGFP in PBS 50 mM buffer pH 7.4 and of HBDI in NaOH 1 M (anionic form) and phosphate-citrate buffer 50 mM pH 5.0 (neutral form) are shown in Fig. 1. Upon irradiation at 355 nm of the model compound HBDI in anionic form, which is the major ionization state in EGFP at pH 7.4, we were able to detect a signal at 1275 nm, which grows with a lifetime of ∼3 μs and decays in 20 μs (Fig. 2). The spectrum of the 20-μs component matches that of 1O2 phosphorescence (Fig. 2, inset), which strongly suggests that this component represents the 1O2 lifetime. Upon addition of the 1O2 quencher sodium azide (6 mM), the lifetime decreased from 20 to ∼5 μs, consistent with a quenching constant, kq, of 5–9 × 107 M−1 × s−1 in basic pH (15), which further supports its assignment to the decay of 1O2 phosphorescence. The 20 μs lifetime is shorter than the natural lifetime of 1O2 in D2O (67 μs (16)), suggesting partial quenching by HBDI. We attribute the 3-μs rise to the formation of 1O2 with the lifetime of the triplet state of anionic HBDI. Irradiation of the neat solvent in the same conditions did not produce any signal at 1275 nm, which further supports that singlet oxygen is produced by the HBDI sample. We cannot rigorously exclude the possibility of an impurity in the sample being the actual photosensitizer; however, that impurity should compete effectively with HBDI for the incoming photons and have the same pH behavior as HBDI. As the purity of the HBDI sample was >95%, we judge this combination of factors unlikely. It is worth noting that basic HBDI solutions are very unstable and experiments were performed on freshly prepared samples. Furthermore, we verified that the degradation product(s) did not contribute to the signal at 1270 nm by carrying out the following two experiments: in the first one, we monitored the intensity of the signal with time and upon extended irradiation of the solution. After light doses 10-fold larger than those used in the previous experiments, the variations of intensity were <20%. In the second series of experiments, we repeated the measurements in acetonitrile/methanol 4:1 with 10 mM NaOH added. This produced better singlet oxygen signals, owing to the larger radiative rate constant in this medium, and allowed us to decrease the number of laser pulses by a factor of 5. The stability of HBDI was also higher in this less-polar and less-protic solvent. The extent of sample degradation was now <10% and under these conditions we measured a quantum yield of singlet oxygen ΦΔ = 0.003 ± 0.001, close to the value in D2O (ΦΔ = 0.004, see below). Thus, we can safely rule out a degradation product as the actual singlet oxygen photosensitizer.

FIGURE 1.

Normalized absorption spectra of the studied compounds: (A) anionic form of HBDI in NaOH 1M (continuous line) and neutral form in phosphate-citrate buffer pH 5.0 (dotted line); (B) EGFP in PBS buffer pH 7.4.

FIGURE 2.

1O2 signal photosensitized by HBDI in the anionic form. A solution of HBDI in NaOH 1M was irradiated with 20,000,000 laser pulses at 355 nm and the concomitant phosphorescence of 1O2 was detected at 1275 nm (100 ns per channel). The signal was fitted by Eq. 1 with lifetimes of 2 μs and 17 μs for the rise and decay, respectively. (Inset) 1O2 phosphorescence spectra obtained from the intensity of the signal at different wavelengths.

For neutral HBDI, we found biexponential decaying signals (3 and 0.6 μs) in the range 950–1350 nm. However, the spectra of none of the components resembled that of 1O2 phosphorescence, and neither their lifetime nor their intensity was affected by saturation with Ar or O2. Thus, no 1O2 was detected in this case.

To quantify the quantum yield of 1O2 photosensitization (ΦΔ), defined as the number of photosensitized 1O2 molecules per absorbed photon, the phosphorescence intensity at time zero, S(0), was compared to that produced by an optically matched reference in the same solvent and at the same excitation wavelength and intensity. S(0), a quantity proportional to ΦΔ, was determined by fitting Eq. 1 to the time-resolved phosphorescence intensity at 1270 nm:

|

(1) |

For the isolated anionic chromophore HBDI (in NaOH 1 M in D2O), ΦΔ = 0.004 ± 0.001 (versus sulfonated phenalenone in the same solvent, ΦΔ = 1 (17)). The value of ΦΔ not only provides information about the efficiency of 1O2 photosensitization, but also represents a lower limit for the intersystem crossing quantum yield in HBDI. We found the same ΦΔ value in acetonitrile/methanol 4:1 with 10 mM NaOH added. The triplet state of GFPs and model chromophores has not been studied in detail, presumably because the low yield of triplet formation (in the 0.001 range judging from singlet oxygen data) challenges the use of transient absorption spectroscopy. Most of the information on this state has been provided by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) and single-molecule experiments (18–20), but no information on the triplet quantum yield has been reported to our knowledge.

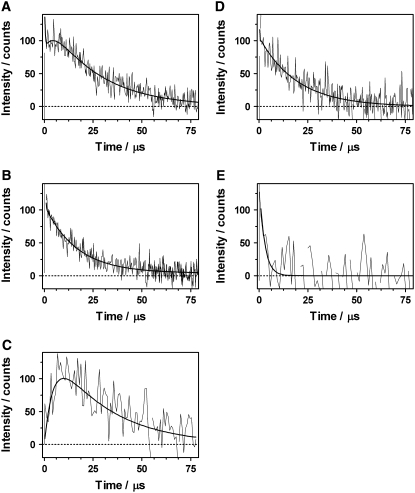

In the case of EGFP in a mixture of PBS and deuterated (D)-PBS (1:3), signals were rather small so a high protein concentration (∼0.2 mM) was needed, which might induce some aggregation. The signal at 1275 nm shows, as in the case of anionic HBDI, a rise followed by a decay, with components of τ1 ≈ 4 μs and τ2 = 25 μs, respectively (Fig. 3 A). It is tempting to directly assign these lifetimes to the formation and decay of 1O2, as above. However, it is worth noting that the preexponential factors of both components were different, i.e., the signal could not be fitted by Eq. 1, and that the spectrum of the long component does not match that of the phosphorescence of 1O2. On the other hand, the 4-μs component only appeared at 1275 nm, suggesting that it is indeed related to 1O2. Experiments performed in 1100–1300 nm region revealed the presence of the kinetic component of 25 μs, which also contributes to the detected signal at 1275 nm. In an attempt to isolate the 1O2 signal, our approach was to normalize the signals at 1275 and 1100 nm (Fig. 3, A and B) and subtract the latter from the former (see Supplementary Material). The resulting signal (Fig. 3 C) could then be fitted by Eq. 1, and rises in 4 μs and decays in 25 μs. Note that, according to Eq. 1, the signal rises with the lifetime τΔ when τT > τΔ, as the preexponential factor is positive in this case.

FIGURE 3.

Normalized emission signals of EGFP in D-PBS irradiated at 532 nm and detected at (A) 1275 nm, 40,000,000 laser pulses, 20 ns per channel, fitted parameters: τ1 = 4.4 μs, τ2 = 26 μs. (B) 1100 nm, 40,000,000 laser pulses, 20 ns per channel, fitted parameter: τ = 20 μs. (C) Signal resulting from panels A and B, fitted parameters: τΔ = 4.5 μs, τT = 28 μs. (D) 1275 nm, [NaN3] = 7 mM, 40,000,000 laser pulses, 20 ns per channel, fitted parameters: τ1 = 0.2 μs, τ2 = 23 μs. (E) 1275 nm, oxygen-saturated D-PBS, 30,000,000 laser pulses, 200 ns per channel, fitted parameter: τ = 3–6 μs.

The addition of azide (7 mM), which should affect the singlet oxygen lifetime and amplitude but not the EGFP triplet lifetime neither its amplitude (see Supplementary Material), eliminated the rise component of the signal at 1275 nm, confirming its attribution to 1O2 phosphorescence. The presumably smaller amplitude of the rise and its faster kinetics precluded a reliable determination of its time constant (Fig. 3 D and Supplementary Material). As to the nature of the 25-μs component observed in the range 1100–1300 nm, we tentatively attribute it to the protein phosphorescence, since saturation with oxygen resulted in a decrease of this component to a few μs (Fig. 3 E). Our triplet-state lifetime value of 25 μs for EGFP would confirm a previous proposed value of ∼30 μs, extracted from FCS measurements on this protein (21). The exceptionally long triplet lifetime of EGFP in air-saturated solution may be explained by the low accessibility of O2 to the chromophore due to its screening by the β-can (22). As for the 1O2 lifetime, which we would expect as ∼11 μs given the proportion of H2O/D2O used (23), the shorter value probably reflects its reaction with the amino acids near the chromophore and/or quenching by the chromophore itself, as found for anionic HBDI.

We have attempted to record the steady-state emission spectrum of EGFP up to 1000 nm at room temperature and also at 77 K (the latter to reduce radiationless deactivation) using a Fluorolog 1500 fluorimeter (Spex Industries, Metuchen, NJ). Unfortunately, this spectrometer lacks the sensitivity to detect the EGFP phosphorescence. Also, we have attempted to extend our time-resolved emission measurements down to 1000 nm (the lower limit of our apparatus) but no maximum could be located in that range either. We must conclude that the phosphorescence maximum must be <1000 nm, i.e., the triplet energy of EGFP is >120 kJ × mol−1.

Due to the presence of an additional signal at 1275 nm, we are not able to quantify the photosensitization ability of EGFP in terms of ΦΔ. In any case, our above results show that the β-can indeed provides shielding of the chromophore and reduces its ability to sensitize 1O2, as judged from the different triplet lifetimes in HBDI and EGFP.

Attempts were also made to detect 1O2 in the red GFP-like protein DsRed. However, we could only find luminescence signals that did not show the spectral signature of 1O2 and that were insensitive to azide. We thus assign them tentatively to phosphorescence from the chromophore.

It is unclear at this point which are the features governing the ability to photosensitize 1O2 by the different GFPs. Some of the factors might be the accessibility of molecular oxygen to the chromophore due, for example, to a looser β-can, or a more suitable triplet energy of the chromophore. The accessibility of oxygen to the chromophore can be related to the maturation time of the GFPs (24), so further work comparing maturation times and 1O2 photosensitization properties might be helpful to elucidate whether this is an important factor. In the comparison of the photosensitizing KillerRed with other mutants of its precursor anm2CP, it was found that the combination of the two mutations Asn-145 and Ala-161 (corresponding to positions 148 and 165 in Aequorea victoria GFP) played a key role in the increase of photosensitizing ability (12). In addition to these two mutations, which are close to the chromophore, other folding mutations were also included in KillerRed and their impact in the phototoxicity was also shown to be considerable (12). The availability of the crystal structures of these proteins might shed light onto this issue, and help to understand the origin of the different phototoxicity in GFP-like proteins.

CONCLUSION

The low efficiency for triplet state formation and 1O2 photosensitization by GFPs is possibly the reason why little was known to date about the kinetic parameters involved in these processes. However, it has been possible to show before (4,6) and also in this work that irradiation of EGFP indeed results in the formation of 1O2. Our results confirm this by providing, for the first time, unequivocal evidence for singlet oxygen production derived from its specific phosphorescence at 1270 nm. Our work goes one step further and also provides kinetic information on the EGFP- (and HBDI) photosensitized formation and decay of 1O2. We find that 1O2 is formed with a lifetime of ∼25 μs, in agreement with the triplet lifetime measured by FCS (21). The extremely long triplet lifetime in aerobic conditions seems to be a direct consequence of the low oxygen accessibility to the chromophore in the β-can. Likewise, the lifetime of 1O2 photosensitized by EGFP (4 μs) is substantially shorter than that of 1O2 produced by the model chromophore HBDI, which suggests that it is being partially quenched by the amino acids surrounding the chromophore in EGFP.

We were unable to estimate a value for ΦΔ in EGFP, but we have shown that this value is 0.004 for HBDI, providing the first estimation on lower limit for the triplet yield of this model compound.

The study of 1O2 photosensitization and its correlation with the protein environment of the chromophore can be helpful in designing more efficient genetically encoded CALI agents. In a similar way, more photostable GFPs with less ROS production can be envisaged for their use in fluorescence microscopy and, in particular, in single molecule spectroscopy where the irradiation conditions are more demanding.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Procedure for recovering the singlet oxygen decay from data at 1270 and 1100 nm. To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Baruah for the synthesis of HBDI, and Mr. C. Heusdens for the expression and purification of EGFP and DsRed.

This work was supported by grants from Institute for Nanoscale Physics and Chemistry (Leuven) and Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia (Barcelona, No. SAF2002-04034-C02-02 and No. CTQ2007-67763-C03-01/BQU). A. J.-B. thanks Generalitat de Catalunya (Departament d'Universitats, Recerca i Societat de la Informacio) and Fons Social Europeu for a predoctoral fellowship.

Editor: Helmut Grubmuller.

References

- 1.Giepmans, B. N. G., S. R. Adams, M. H. Ellisman, and R. Y. Tsien. 2006. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 312:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remington, S. J. 2006. Fluorescent proteins: maturation, photochemistry and photophysics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16:714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixit, R., and R. Cyr. 2003. Cell damage and reactive oxygen species production induced by fluorescence microscopy: effect on mitosis and guidelines for non-invasive fluorescence microscopy. Plant J. 36:280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenbaum, L., C. Rothmann, R. Lavie, and Z. Malik. 2000. Green fluorescent protein photobleaching: a model for protein damage by endogenous and exogenous singlet oxygen. Biol. Chem. 381:1251–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halliwell, B., and J. M. C. Gutteridge. 1999. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- 6.Bell, A. F., D. Stoner-Ma, R. M. Wachter, and P. J. Tonge. 2003. Light-driven decarboxylation of wild-type green fluorescent protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:6919–6926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tour, O., R. M. Meijer, D. A. Zacharias, S. R. Adams, and R. Y. Tsien. 2003. Genetically targeted chromophore-assisted light inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1505–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surrey, T., M. B. Elowitz, P.-E. Wolf, F. Yang, F. Nédélec, K. Shokat, and S. Leibler. 1998. Chromophore-assisted light inactivation and self-organization of microtubules and motors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:4293–4298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raijfur, Z., P. Roy, C. Otey, L. Romer, and K. Jacobson. 2002. Dissecting the link between stress fibers and focal adhesions by CALI with EGFP fusion proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanabe, T., M. Oyamada, K. Fujita, P. Dai, H. Tanaka, and T. Takamatsu. 2005. Multiphoton excitation-evoked chromophore-assisted laser inactivation using green fluorescent protein. Nat. Methods. 2:503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitriol, E. A., A. C. Uetrecht, F. M. Shen, K. Jacobson, and J. E. Bear. 2007. Enhanced EGFP-chromophore-assisted laser inactivation using deficient cells rescued with functional EGFP-fusion proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:6702–6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulina, M. E., D. M. Chudakov, O. V. Britanova, Y. G. Yanushevich, D. B. Staroverov, T. V. Chepurnykh, E. M. Merzlyak, M. A. Shkrob, S. Lukyanov, and K. A. Lukyanov. 2006. A genetically encoded photosensitizer. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonell, S., and S. E. Braslavsky. 2000. Time-resolved singlet oxygen detection. Methods Enzymol. 319:37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima, S., H. Ohkawa, T. Hirano, S. Maki, H. Niwa, M. Ohashi, S. Inouye, and F. I. Tsuji. 1998. Fluorescent properties of model chromophores of tyrosine-66 substituted mutants of Aequorea green fluorescent protein (GFP). Tetrahedron Lett. 39:5239–5242. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson, F., W. P. Helman, and A. B. Ross. 1995. Rate constants for O2(1Δg) decay and quenching. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 24:663–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scaiano, J. C. 1989. CRC Handbook of Organic Photochemistry. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 17.Nonell, S., M. Gonzalez, and F. R. Trull. 1993. 1H-Phenalen-1-one-2-sulfonic acid—an extremely efficient singlet molecular oxygen sensitizer for aqueous media. Afinidad. 50:445–450. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widengren, J., Ü. Mets, and R. Rigler. 1999. Photodynamic properties of green fluorescent proteins investigated by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. 250:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotlet, M., J. Hofkens, F. Köhn, J. Michiels, G. Dirix, M. Van Guyse, J. Vanderleyden, and F. C. De Schryver. 2001. Collective effects in individual oligomers of the red fluorescent coral protein DsRed. Chem. Phys. Lett. 336:415–423. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung, G., S. Mais, A. Zumbusch, and C. Bräuchle. 2000. The role of dark states in the photodynamics of the green fluorescent protein examined with two-color fluorescence excitation spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 104:873–877. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haupts, U., S. Maiti, P. Schwille, and W. W. Webb. 1998. Dynamics of fluorescence fluctuations in green fluorescent protein observed by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:13573–13578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsien, R. Y. 1998. The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:509–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweitzer, C., and R. Schmidt. 2003. Physical mechanisms of generation and deactivation of singlet oxygen. Chem. Rev. 103:1685–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evdokimov, A. G., M. E. Pokross, N. S. Egorov, A. G. Zaraisky, I. V. Yampolsky, E. M. Merzlyak, A. N. Shkoporov, I. Sander, K. A. Lukyanov, and D. M. Chudakov. 2006. Structural basis for the fast maturation of Arthropoda green fluorescent protein. EMBO Rep. 7:1006–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]