Abstract

The function of telomeres is twofold: to facilitate complete chromosome replication and to protect chromosome ends against fusions and illegitimate recombination. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, interactions among Cdc13p, Stn1p, and Ten1p are thought to be critical for promoting these processes. We have identified distinct Stn1p domains that mediate interaction with either Ten1p or Cdc13p, allowing analysis of whether the interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p is indeed essential for telomere capping or length regulation. Consistent with the model that the Stn1p essential function is to promote telomere end protection through Cdc13p, stn1 alleles that truncate the C-terminal 123 residues fail to interact with Cdc13p and do not support viability when expressed at endogenous levels. Remarkably, more extensive deletions that remove an additional 185 C-terminal residues from Stn1p now allow cell growth at endogenous expression levels. The viability of these stn1-t alleles improves with increasing expression level, indicating that increased stn1-t dosage can compensate for the loss of Cdc13p–Stn1p interaction. However, telomere length is misregulated at all expression levels. Thus, an amino-terminal region of Stn1p is sufficient for its essential function, while a central region of Stn1p either negatively regulates the STN1 essential function or destabilizes the mutant Stn1 protein.

TELOMERES are nucleoprotein complexes at the termini of linear eukaryotic chromosomes that perform a critical role in maintaining genome stability. At the DNA level, telomeres typically comprise long double-stranded tracts of a repetitive GT/CA-rich sequence, terminating in a short single-stranded 3′ overhang that corresponds to the strand bearing the G-rich repeats. A large number of proteins associate with the telomere repeats to form a structure that allows telomeres to act as “caps” that protect chromosome ends from degradation and illegitimate end-to-end fusions. Chromosomes are considered capped if they preserve the physical integrity of the telomere while allowing cell division to proceed (Blackburn 2000). Proteins that bind to the duplex portion of telomeres, such as TRF1 and TRF2 in mammalian cells and Rap1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as well as proteins that bind the single-strand overhang, such as POT1 in mammalian cells and Cdc13p in S. cerevisiae, are essential for proper telomere structure and function (Smogorzewska and De Lange 2004; De Lange 2005; Songyang and Liu 2006). In addition to their protective function, telomeres facilitate complete replication of chromosome ends, by promoting extension of the telomere repeats through telomerase activity (Smogorzewska and De Lange 2004). The conventional DNA replication machinery is responsible for subsequently filling in the extended single-stranded repeats added by telomerase (Chakhparonian and Wellinger 2003).

The two primary functions of telomeres as chromosome caps and facilitators of chromosome end replication are complementary. First, the length of the telomeres has to be sufficient to allow capping to function properly. As evidence of this, cells lacking telomerase gradually shorten the length of their telomeres as they proliferate, leading to the eventual detection of their compromised chromosome ends as “damaged DNA” with concomitant cell cycle arrest (As and Greider 2003; Gire 2004). Second, telomeres must function as caps throughout the cell cycle, even during S phase when the DNA replication machinery accesses the ends of each chromosome. Thus, the chromosome end protection requirements are expected to be distinct during S phase, and it may be expected that different nucleoprotein complexes or structures exist at telomeres to promote capping at different points in the cell cycle (Blackburn 2001).

In S. cerevisiae, telomere function is critically dependent upon three essential genes, CDC13, STN1, and TEN1. Cdc13p, Stn1p, and Ten1p have been proposed to form a complex that associates with the G-rich telomere strand that both prevents chromosome degradation and facilitates complete telomere replication (Garvik et al. 1995; Nugent et al. 1996; Grandin et al. 1997, 2001). Pair-wise interactions have been demonstrated among the Cdc13, Stn1, and Ten1 proteins (Grandin et al. 1997, 2001; Petreaca et al. 2006). The functional significance of the contacts among these proteins is not well understood, although it has been proposed that the roles of Stn1p in telomere capping and in regulating telomere length is mediated through its interaction with Cdc13p (Grandin et al. 1997; Pennock et al. 2001). This hypothesis has not been directly tested.

Of these three proteins, the function of Cdc13p is the most clear. Cdc13p has been shown to bind to the single-stranded G-rich telomeric DNA in vitro (Lin and Zakian 1996; Nugent et al. 1996). Current models propose that telomere-bound Cdc13p both acts as a physical cap to prevent degradation of the chromosome end and acts as a platform to coordinate telomere elongation by telomerase with subsequent telomere fill-in synthesis through recruitment or regulation of both telomerase and the DNA replication machinery during S-phase (Lustig 2001; Chakhparonian and Wellinger 2003). Analysis of the temperature sensitive cdc13-1 allele has been key for probing the function of CDC13 in telomere capping. At high temperature, there is extensive loss of DNA corresponding to the G-rich strand at telomeric and subtelomeric regions and activation of the RAD9 dependent checkpoint (Weinert and Hartwell 1993; Garvik et al. 1995; Lydall and Weinert 1995). Evidence that the loss of the C strand is generated at least in part from nucleolytic degradation comes from analysis of resection of a DNA double-strand break created adjacent to a tract of telomere sequence; cells arrested in G2/M were found to require Cdc13p to prevent resection from this break (Diede and Gottschling 1999). The essential role of Cdc13p in telomere capping may be cell-cycle specific, since telomeres in G1-arrested cells maintain integrity in the absence of functional Cdc13p (Lydall and Weinert 1995; Polotnianka et al. 1998; Vodenicharov and Wellinger 2006). Consistent with a cell-cycle-dependent function, Cdc13p shows maximal association with telomere chromatin during S phase (Taggart et al. 2002).

The discovery of the role of CDC13 in the telomerase recruitment pathway came through identification of the cdc13-2est allele, which displays progressive telomere shortening and senescence similar to the null alleles of the telomerase holoenzyme genes (Lendvay et al. 1996; Nugent et al. 1996). Data showing both genetic and physical links between Cdc13p and Est1p, a telomerase-associated protein, has led to the hypothesis that during S phase Cdc13p recruits Est1p to telomeres, activating telomerase (Evans and Lundblad 1999; Qi and Zakian 2000; Pennock et al. 2001; Taggart et al. 2002). In addition to its role as a positive regulator of telomere length, CDC13 can function as a negative regulator of telomere length, since compromised cdc13 function can lead to increased telomere length (Nugent et al. 1996; Grandin et al. 2000; Chandra et al. 2001). The role of Cdc13p as a negative regulator may be related to its physical interaction with Stn1p and Ten1p, or with Pol1p, the catalytic subunit of polymerase-α that synthesizes the DNA portion of the short RNA/DNA primer that initiates DNA synthesis during semiconservative DNA replication (Qi and Zakian 2000). Reduced function of several genes associated with semiconservative DNA replication, including POL1, lead to elongated telomeres (Adams and Holm 1996; Grossi et al. 2004).

Unlike the role of Cdc13p, the role of Stn1p in telomere function is less clear. Similar to CDC13, the loss of STN1 function was shown through analysis of the stn1-13 allele to display extensive single-stranded telomere G strands when strains were grown at semipermissive temperature (Grandin et al. 1997). Experiments in which transcription of STN1 from a GAL promoter was repressed showed that the DNA damage checkpoint is activated in a RAD9- dependent fashion when Stn1p levels become limited (Grandin et al. 1997). The Cdc13 and Stn1 proteins have been proposed to function as part of a complex that promotes telomere integrity (Grandin et al. 1997; Pennock et al. 2001). However, a STN1- and TEN1-dependent pathway also exists that can mediate telomere end protection in the complete absence of CDC13. Thus either Cdc13p and Stn1p share redundant functions that promote telomere capping or Stn1p can facilitate a separate capping mechanism (Petreaca et al. 2006).

In addition to its role in chromosome end protection, and similarly to CDC13, STN1 plays a role in negatively regulating telomere extension by telomerase (Grandin et al. 1997; Chandra et al. 2001; Pennock et al. 2001), although the molecular mechanism by which Stn1p accomplishes this function is not well understood. The loss of STN1 function results in substantial telomere extension (Grandin et al. 1997; Grossi et al. 2004), whereas increasing the levels of STN1 mRNA through interference with the nonsense-mediated RNA degradation pathway leads to a marked decrease in telomere length (Dahlseid et al. 2003). It is possible that the negative regulation of telomerase by Stn1p is mediated through its interaction with Cdc13p. It has been proposed that such an interaction could compete or interfere with the Cdc13p–Est1p interaction, and thus attenuate telomerase activity (Chandra et al. 2001; Pennock et al. 2001). The mechanism may not be so simple, however, as Stn1p also associates with Pol12p, the B subunit of polymerase-α (Grossi et al. 2004). This Stn1p–Pol12p interaction has been proposed to facilitate synthesis of the telomere C strand following telomerase-mediated TG1–3 extension (Grossi et al. 2004), and the act of filling in the telomere C strand has been suggested to lead to telomerase inhibition (Fan and Price 1997). These observations suggest that interactions of Stn1p with Cdc13p and/or with Pol12p may be critical for STN1 to function as a negative regulator of telomere elongation.

In this study, we analyze the contribution of domains of Stn1p to interaction with Cdc13p and to its functions in telomere maintenance. Through this approach, we assess the phenotypic consequences of abrogating the interaction between Stn1p and Cdc13p, allowing us to address the significance of this association. We report here that the amino terminus of Stn1p contributes to both the essential telomere-capping and length-regulation functions of STN1, while the carboxyl terminus of Stn1p, which interacts with Cdc13p, contributes to telomere-length regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains:

All strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1. All strains used for phenotypic analysis are derivatives of YPH499 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). Strains were created by matings and tetrad dissections, using standard yeast genetic methods. Unless indicated otherwise, strains were grown at 30°. To generate strains expressing the STN1 plasmid constructs in a stn1-null background, the plasmids encoding the stn1 alleles were first transformed into the appropriate haploid stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 strain carrying pVL1046 (STN1 on a CEN-URA3 plasmid). The pVL1046 was then shuffled out of the strain by plating on media containing 0.005744 mol/liter 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA). The stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles were created by integration of a PCR product into a diploid such that the portion of STN1 encoding amino acids 187–494 or 282–494 is replaced by a stop codon, followed by a kanamycin resistance cassette. The template for the PCR was the pFA6MX2 plasmid, which encodes the kanamycin resistance cassette (Wach et al. 1994). The oligonucleotides used for this PCR are: CO161 (stn1-281t forward primer) cggtttgtatcgtcgctaaaggattttcctgaaactcactttttgaatgacagctgaagcttcgtacgc, CO162 (stn1-186t forward primer) gaaaatcacaatgaacatgcgtgagcaacttgacacgccttggtcctttgacagctgaagcttcgtacgc, and CO163 (reverse primer) caggcctagagagatgcgccgttattgacgatgcgagttttctaacaaagcataggccactagtggatctg. The PCR products are targeted to the appropriate sites for integration through sequence homology at the termini of the amplified fragments. Correct integrants were identified by PCR verification of the integration junctions.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pJ694A | MATatrp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2∷ GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE met2∷GAL7-lacZ | James et al. (1996) |

| dCN157 | MATa/α cdc13-1stn1-Δ∷KanMX2CFa CDC13 STN1 | This study |

| dCN187 | MATa/α est2-Δ∷URA3CDC13myc(18)∷HIS3stn1-186t∷KanMX2CFa EST2 CDC13 STN1 | This study |

| dCN188 | MATa/α est2-Δ∷URA3CDC13myc(18)∷HIS3stn1-281t∷KanMX2CFa EST2 CDC13 STN1 | This study |

| dCN325 | MATa/α est2-Δ∷URA3stn1-186t∷KanMX2/CFa EST2 STN1 | This study (mating) |

| hC18 | MATayku80-Δ∷kanMX2 CDC13myc18x∷HIS3 | This study |

| hC35 | MATastn1-Δ∷kanMX2 CFa + pVL1046 | This study |

| hC160 | MATα ura3-52 ade2-101 lys2-801 leu2-Δ1 his3-Δ200 | This study |

| hC276.1 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN1 | This study |

| hC276.234 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN234 | This study |

| hC276.235 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN235 | This study |

| hC276.249 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN249 | This study |

| hC276.F12 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN186 | This study |

| hC276.M17 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN185 | This study |

| hC276.pACT | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pACT2.2 | This study |

| hC276.R1 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN181 | This study |

| hC276.R7 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1046, pCN183 | This study |

| hC567 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN234 | This study |

| hC568 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN235 | This study |

| hC569 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN249 | This study |

| hC572 | MATα CDC13MYC(18X)∷HIS3 stn1-Δ∷KanMX2 + pCN1 | This study |

| hC619 | MATastn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pVL1066 | This study |

| hC622 | MATastn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN318 | This study |

| hC626 | MATastn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN319 | This study |

| hC630 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 + pCN320 | This study |

| hC671 | MATastn1-281t∷kanMX2 CFa | This study |

| hC672 | MATastn1-186t∷kanMX2 CFa | This study |

| hC1110 | MATastn1-186t∷kanMX2 rad52-Δ∷LYS2 CFa | This study |

| hC1545 | MATastn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad52-Δ∷LYS2 + pVL1046 | This study |

| hC1577 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046 | This study |

| hC1612 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pCN181 | This study |

| hC1613 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pCN234 | This study |

| hC1614 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pCN235 | This study |

| hC1615 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pCN249 | This study |

| hC1670 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046, YCplac181 | This study |

| hC1671 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046, pVL1066 | This study |

| hC1672 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046, pCN318 | This study |

| hC1673 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046, pCN319 | This study |

| hC1674 | MATα stn1-Δ∷kanMX2 rad9-Δ∷TRP1 + pVL1046, pCN320 | This study |

CF: [ura3∷TRP1 SUP11 CEN4 D8B].

Plasmids:

The plasmids used in these experiments are listed in Table 2. The plasmids for the two-hybrid assay were created as follows: pCN249 (pADHSTN11–186) was created by ligating the STN1 NcoI–AflII fragment from pVL1046 with NcoI–SmaI sites of pACT2.2. (The AflII site was filled in.) pCN235 (pADHSTN11–281) was created by subcloning a STN1 NcoI–EcoRI fragment into pACT2.2 (NcoI–EcoRI). For pCN234 (pADHSTN11–371), the STN1 NcoI–XmnI fragment was ligated with NcoI–SmaI sites of pACT2.2. The plasmids encoding the C-terminus region of Stn1p and full-length Stn1p (pACT2.2-STN1, pACT-STN1173–494, pACT-STN1187–494, and pACT2-STN1288–494) were isolated from a screen for Cdc13p interacting proteins; both pACT and pACT2 S. cerevisiae libraries were used (a gift from S. Elledge). To create pAS1-TEN1, the full-length TEN1 ORF was amplified by PCR, ligated with the pYES2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subcloned into NcoI–BamHI sites of pAS1. To create plasmids expressing the stn1 alleles from the STN1 native promoter on high-copy 2μ plasmids, the NcoI–PstI STN1 fragments from pCN234, pCN235, and pCN249 were subcloned into NcoI–PstI digested pVL1066 to generate pCN318 (pnativeSTN11–371), pCN319 (pnativeSTN11–281), and pCN320 (pnativeSTN11–186), respectively.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pCN181 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN11–494 (pACT2.2 vector) | Petreaca et al. (2006) |

| pCN234 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN11–371 (pACT2.2 vector) | This study |

| pCN235 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN11–281 (pACT2.2 vector) | This study |

| pCN249 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN11–186 (pACT2.2 vector) | Petreaca et al. (2006) |

| pCN183 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN15–494 (pACT vector) | This study |

| pCN184 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN1173–494 (pACT vector) | This study |

| pCN185 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN1187–494 (pACT vector) | This study |

| pCN186 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 AD-fused STN1288–494 (pACT2 vector) | Petreaca et al. (2006) |

| pCN124 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 DBD-fused TEN1 (pAS1 vector) | Petreaca et al. (2006) |

| pVL705 | 2μ LEU2 ADH promoter GAL4 DBD-fused CDC13Δ585–677 (pAS1 vector) | Chandra et al. (2001) |

| pVL1046 | CEN URA3 native promoter STN11–494 (YCplac33 vector) | This study |

| pVL1066 | 2μ LEU2 native promoter STN11–494 (YEplac181 vector) | Pennock et al. (2001) |

| pCN318 | 2μ LEU2 native promoter STN11–371 (YEplac181 vector) | This study |

| pCN319 | 2μ LEU2 native promoter STN11–281 (YEplac181 vector) | This study |

| pCN320 | 2μ LEU2 native promoter STN11–186 (YEplac181 vector) | Petreaca et al. (2006) |

| pCN1 | CEN LEU2 native promoter STN11–494 (YCplac111 vector) | This study |

Serial dilution assays:

For assays using serial dilutions of strains, a single colony was inoculated in 5 ml YPD or selective media and grown for 3–4 days at 23° or 30°. Tenfold serial dilutions were prepared in microtiter dishes, and then equivalent amounts of each dilution were stamped on appropriate media. The plates were incubated 4–5 days at 23°, 3–4 days at 30°, and 2.5 days at 36°, unless otherwise noted.

Two-hybrid assay:

Yeast two-hybrid assays were done using the pJ694A strain (MATa trp1 leu2 ura3 his3 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2∷GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2∷GAL7-lacZ), which uses three reporter genes to test protein interaction (James et al. 1996). Transformed strains containing the test plasmids were propagated on minimal media lacking leucine and tryptophan. Cultures were grown in 5 ml Leu−Trp− media for 4 days, and then 10-fold serial dilutions were stamped onto Leu−Trp−, Leu−Trp−Ade−, and Leu−Trp−His− plates supplemented with 1.5 mm 3-aminotriazole (3-AT, ARCOS), to analyze reporters. Plates were incubated at 30° for 3 days. On the third day, an X-gal overlay was performed to assay for β-gal activity (Chandra et al. 2001).

Western blots:

Strains were grown at 30° in 50 ml of YPD or selective media to OD600 ∼ 0.8, and then cells were spun down and lysed by bead beating in SUMEB buffer (1% SDS, 8 m urea, 10 mm MOPS, pH 6.8, 10 mm EDTA, 0.01% bromophenol blue) or buffer A (25 mm HEPES at pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, 10% glycerol and 1% Triton-X). For SDS–PAGE, each lane contains either 50 μl of lysates made in SUMEB buffer or 400 μg of lysates made in buffer A. The gels were 10% polyacrylamide, and the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The blots were probed with an anti-HA mouse monoclonal primary antibody (12CA5), followed by a goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary. A Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, CT) Renaissance chemiluminescence reagent was used to visualize the antibodies following exposure on Fuji film. To detect Rad53p phosphorylation, strains were either grown in YPD or treated with 0.1% MMS for 2.5 hr at 30°. Cells were lysed in 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and 50 μl of each lysate was run on a 10% 30:0.39 acrylamide:bisacrylamide gel (Sanchez et al. 1996). The protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with an anti-Rad53p (Sc6749) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Southern blots:

Cell cultures were grown to saturation at 30°, and genomic DNA was prepared as previously described (Lundblad and Szostak 1989). To assess telomere length, genomic DNA was either digested with XhoI and run on a 0.8% agarose gel, or digested with a combination of enzymes that each have four base pair recognition sites (HaeIII, AluI, HinfI, and MspI) and run on a 1.3% agarose gel (Teng and Zakian 1999). Following transfer to Hybond-XL membranes (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), [32P]dGT/CA was used to detect telomere repeats. To monitor a single telomere, DNA was digested with XhoI, run on a 1% gel and probed with a 32P-labeled probe that hybridizes uniquely to the right arm of chromosome VI, as described in Zubko and Lydall (2006). All blots were exposed on Fuji film.

Single-stranded DNA analysis:

Cells were grown in liquid YPD to an OD600 ∼ 1 then DNA was isolated as previously described (Dionne and Wellinger 1996). Fifty micrograms of DNA were digested with ExoI for 2 hr and an equal amount of DNA was mock treated. For mung bean treatment, 100 μg of DNA were treated with 30 units of enzyme for 2.5 hr; an equal amount of DNA was mock treated. The mock, ExoI and mung bean digested DNA samples were then digested overnight with XhoI, and the DNA was analyzed by in-gel hybridization, as described by Bertuch and Lundblad (2003). The probe used was an oligonucleotide that hybridizes to the telomere G strand (5′ ccaccacacacacccacaccc 3′) (Dionne and Wellinger 1996), kinased using radiolabeled [32P]ATP. Gels were exposed to a Phosphoimager screen (Amersham). The exposed native gels were then denatured and reprobed to analyze total DNA, as described by Dionne and Wellinger (1996).

Cell-cycle analysis:

To analyze the cell-cycle dynamics of the stn1 mutants, the protocol described in Bachant et al. (2002) was used. Five milliliters of each strain was grown to an OD of 1.5. Strains were synchronized in G1 by arresting with 5μg/ml α-factor in YPD pH 3.9. The cells were washed twice with 5 ml TBS to remove the α-factor, and released into YPD at an OD of 1.0. One-half-milliliter aliquots of cells were fixed in 95% ethanol every 15 min. Ten micrograms per milliliter α-factor were re-added at 75 min postrelease to allow resynchronization in G1. Cells were then rehydrated in TBS, treated with 1 mg/ml RNase A overnight, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by FACS on a FACS SCAN machine.

RESULTS

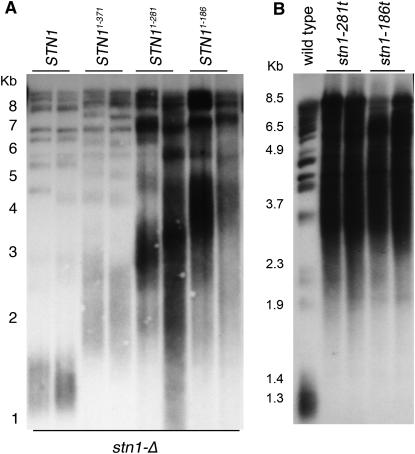

Nonoverlapping regions of Stn1p interact with Ten1p and Cdc13p:

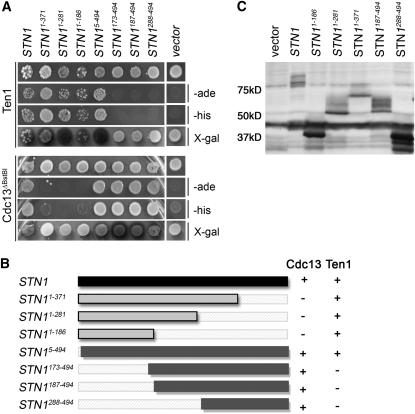

In a previous publication, we reported that the Stn1p domains required for interaction with Cdc13p and Ten1p appear to be separable (Petreaca et al. 2006). As assayed in the yeast two-hybrid system, Stn1p288–494 is sufficient for interaction with Cdc13p whereas Stn1p1–186 is sufficient for interaction with Ten1p. Thus, it may be possible to determine the functional significance of the Cdc13p–Stn1p interaction without disrupting the Stn1p–Ten1p interaction. Here we report a more complete analysis of the associations of Stn1p truncations with either Cdc13p or Ten1p (Figure 1A). Five clones encoding full-length or truncated Stn1p were isolated from a cDNA library in a two-hybrid screen with the pAS1–Cdc13Δ585–677 construct (Figure 1A); the truncations remove up to the first 287 amino acids of Stn1p. These Stn1p constructs also interact with full-length Cdc13p in the two-hybrid assay (data not shown), indicating that the portion of the Cdc13p DNA binding domain encoded between the BstBI restriction sites does not affect its two-hybrid interaction with Stn1p. When tested for interaction with Ten1p, the full-length Stn1p constructs, but not the truncations lacking the amino terminus, were competent for Ten1p interaction. To test whether the Stn1p amino terminus was sufficient for Ten1p interaction, three constructs that truncate the Stn1p carboxyl terminus were created by subcloning. The Stn1p constructs lacking the C terminus do interact with Ten1p, although none activate any of the two-hybrid reporters when tested with either Cdc13p or Cdc13pΔ585–677 (Figure 1A and data not shown). Together, these data indicate that the carboxyl-terminal 207 amino acids (Stn1p288–494) are sufficient for interaction with Cdc13p in the two-hybrid system, and Stn1p truncations lacking residues 372–494 cannot interact with Cdc13p in this assay. Conversely, the first 186 amino acids of Stn1p are sufficient for Ten1p interaction, whereas those that lack amino acids 6–173 fail to interact with Ten1p. As summarized in Figure 1B, the Stn1p regions that interact with Ten1p and Cdc13p are indeed nonoverlapping, requiring either the amino terminus or carboxyl terminus, respectively.

Figure 1.—

Separable domains of Stn1p interact with Ten1p and Cdc13p. (A) Two-hybrid assay with pACT2.2-STN1 full-length and truncation constructs vs. pAS1-TEN1 (pCN124) or pAS1-CDC13Δ585–677 (pVL705). The “empty” pACT2.2 plasmid was used as a vector control. Three reporters for the interaction were tested by assessing growth on Ade−Leu−Trp− plates, growth on His−Leu−Trp− + 1.5 mm 3AT plates, and β-Gal production in X-GAL overlays on Leu−Trp− plates. The top row in each set shows growth on Leu−Trp− plates. (B) Diagram of STN1 constructs used in the two-hybrid assay and summary of interactions. The Stn1p amino acids translated from each STN1 construct are indicated in superscript. A + or − indicates whether the construct is competent for interaction with pCN124 (Ten1p) or pVL705 (Cdc13Δ585–677). (C) Western blot showing relative levels of Stn1p produced from the two-hybrid plasmids in a wild-type strain (hc160). The vector control plasmid is pACT2.2. Strains were grown at 30°, protein was extracted in SUMEB buffer, and 50 μl of each protein lysate was run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. The Western blot was probed with α-HA antibody (12CA5).

To ascertain if the protein-expression level could affect the results of the two-hybrid assay, leading to a “false negative” in the assay, a Western blot was performed on strains expressing the various Stn1p two-hybrid constructs. As shown in Figure 1C, while the expression level of the truncations did vary, the differences are not likely to account for the observed interaction patterns since the two smallest Stn1p fragments reproducibly showed the highest expression level. Combined with the finding that each Stn1p truncation interacts with at least one of its binding partners, it is likely that the truncation proteins are not misfolded and that the two-hybrid results report the regions that are required for in vivo interaction with Cdc13p and Ten1p. Our efforts to show the Stn1p–Cdc13p interaction through co-immunoprecipitation from soluble protein extracts have not been successful. It is possible that this interaction is transient, unstable, or in a subcellular fraction that is difficult to sample biochemically.

The amino terminus of Stn1p is necessary and sufficient for viability:

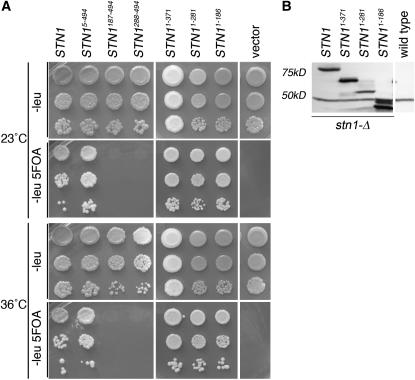

Since the regions of Stn1p that interact with Cdc13p and Ten1p are separable, the hypothesis that Cdc13p interaction with Stn1p is essential for telomere capping can be directly tested. First, the STN1 constructs used in the two-hybrid assay were tested for complementation of a stn1-Δ null mutation. The protein levels of the STN1 truncations when overexpressed in a wild-type strain were at least as abundant as that of the full-length Stn1 protein (Figure 1C). To test for viability, a plasmid shuffle assay was used, plating stn1-Δ strains containing both a full-length STN1 plasmid (CEN-URA3) and the STN1 two-hybrid plasmid (2μ-LEU2, ADH promoter) on media containing 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA), which allows only ura3 strains to survive. Constructs encoding amino-terminal portions of Stn1p can complement the stn1 null allele, even at high temperature (36°) (Figure 2A), suggesting that this region encodes the essential STN1 activities. This data is consistent with a recent report that overexpressing the Stn1p amino terminus can complement the stn1-Δ allele (Gao et al. 2007). Conversely, constructs encoding only carboxyl-terminal portions of Stn1p cannot complement the stn1-Δ null (Figure 2A), indicating that the region of Stn1p necessary and sufficient for its essential function maps to its amino-terminal 186 amino acids. The expression level of the mutant Stn1 proteins in the stn1-Δ cells was at least as high as that of the full length Stn1p, with the exception of Stn1p1–281, which tends to be present at somewhat reduced levels (Figure 2B). Analysis of the growth phenotype of the viable stn1 strains by single-colony streakouts did not reveal any obvious growth defects such as greatly reduced plating efficiency, or altered colony size, or morphology as compared with wild-type strains (data not shown). Since Cdc13p associates with the carboxyl-terminal portion of Stn1p, these data indicate that interaction with Cdc13p is dispensable for viability.

Figure 2.—

The interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p is not required for viability. (A) Assay of ability of stn1 truncation alleles to complement the stn1 null. Single colonies of hC276 strains [stn1-Δ/pVL1046 (STN1 on a CEN-URA3 plasmid)] that had been transformed with the STN1 two-hybrid plasmids (pADH, 2μ, and LEU2) were inoculated into liquid media and grown for 4 days at 23°. Serial 10-fold dilutions of these cultures were plated on Leu− or Leu− 5-FOA plates and incubated at 23°, 30°, and 36°. (30° plates not shown). Cells that grow on 5-FOA have lost the pVL1046 plasmid encoding full-length STN1. Complementation of stn1-Δ is determined by the ability of the cells to grow on Leu− 5-FOA. (B) Western blot comparing protein expression from the STN1 two-hybrid plasmids in the hc276 stn1-Δ strain. Protein extracts were prepared in buffer A from strains that grew on Leu− 5-FOA in (A) and 400 μg of each protein lysate was run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. “Wild-type” strains are hC572, which express untagged STN1 (pCN1).

Expression level and Stn1p central domain affect stn1-Δ complementation by stn1-t alleles:

The STN1 two-hybrid constructs overproduce proteins fused at their amino terminus with the GAL4 activation domain and an HA epitope tag; both the expression level and N-terminal fusion are factors that have the potential to affect the interpretation of the normal function of Stn1p domains. Therefore, high-copy plasmid (2μ) constructs that eliminated the fusion and used the STN1 promoter to drive expression of the STN1 truncations were created. Expressing the stn11–186, stn11–281, and stn11–371 alleles from the high-copy 2μ plasmid allowed viability in the absence of STN1 (Figure 3, A and B). Similar to the data from the two-hybrid constructs, the stn11–186 and stn11–281 truncation alleles could complement stn1-Δ at any temperature (Figure 3, A and C). However, cells expressing stn11–371, which encodes amino acids 1–371 and thus is the least truncated form of Stn1p, showed variability in whether the plasmid could effectively complement the stn1-Δ. As shown in Figure 3B, some colonies could complement viability well while other colonies showed greatly reduced plating efficiency. Streak-outs of multiple independent colonies from three independent transformations showed similar colony-to-colony variability in the viability on 5-FOA plates at 30° (data not shown). Given that this truncation allele fully complements the null when expressed from the ADH promoter, it is possible that when the native STN1 promoter drives expression, fluctuation in the number of 2μ plasmids in the cell affects the viability of the stn1-Δ/pstn11–371 cells. Thus, to our surprise, more extensive deletions of residues from the Stn1p C terminus actually improve stn1-Δ cell viability.

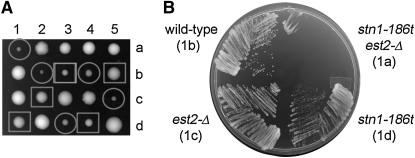

Figure 3.—

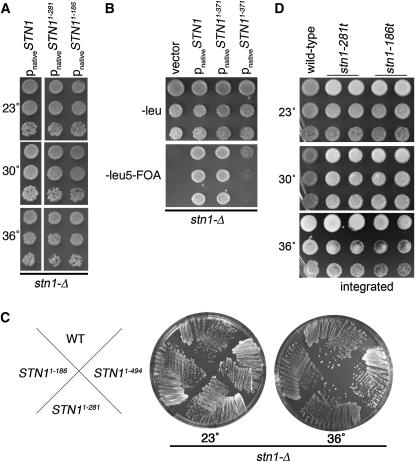

Strains expressing stn1 residues 1–186 or 1–281 are more viable than strains expressing stn1 residues 1–371. (A) Test for complementation of stn1-Δ by pstn11–281 and pstn11–186 when expressed from the STN1 promoter on 2μ plasmids. Shown are stn1-Δ haploids covered by the indicated plasmids, obtained by dissection of the dCN157 diploid strain (stn1-Δ/STN1) that was transformed with the pVL1066, pCN319, or pCN320 plasmids. Cells were grown to similar densities at 23° in Leu− liquid media. Serial 10-fold dilutions were stamped on Leu− plates and incubated at 23°, 30°, and 36°. (B) pstn11–371 shows variability in its extent of stn1-Δ complementation when expressed from the STN1 promoter on a 2μ plasmid. The stn1-Δ/pVL1046 (pSTN1 on a URA3 plasmid) strain (hc35) that had been transformed with either the pCN318 or pCN1066 plasmids was grown in liquid culture at 30° for 3 days. Serial 10-fold dilutions of these cultures were plated on Leu− or Leu− 5-FOA and incubated at 30°. Cells that grow on 5-FOA have lost the pVL1046 plasmid encoding STN1. Two independent pstn11–371 transformants are shown. (C) Single-colony streakouts of strains in A, grown 5 days at 23° and 3 days at 36°. WT, wild-type strain (hC160). No significant deviation from wild-type growth was observed. (D) Growth phenotype of integrated stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles on YPD. Shown are serial 10-fold dilutions of cultures of stn1-186t and stn1-281t colonies (two each) that were obtained from dissection of dCN187 and dCN188, compared with a wild-type haploid. The alleles are integrated at the chromosomal STN1 locus, truncating the wild-type STN1 gene.

We next tested whether the stn1-t alleles remain viable when expressed at endogenous levels from the normal STN1 locus. The truncation alleles of STN1 were created in diploids by integrating a stop codon followed by the KanMX2 drug-resistance cassette in place of the sequences that encode the carboxyl-terminal portion of Stn1p. Following dissection of the resulting heterozygous diploids, both the stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles, encoding amino acids 1–186 and 1–281, respectively, were found to be viable as haploids (Figure 3D). (Note that we are naming the integrated truncation alleles stn1-186t, stn1-281t, and stn1-371t, whereas the alleles expressed from plasmids are denoted with the expressed residues in superscript, e.g., stn11–186.) The stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains are not temperature sensitive but do grow more slowly than wild-type strains (Figure 5B). The essential function of STN1 is proposed to be in telomere capping, and we would thus expect mutants with end-protection defects to be lethal. Therefore, the viability of these stn1 truncation alleles reveals that the carboxyl terminus of Stn1p is not absolutely required for chromosome end protection. On the other hand, no viable stn1-371t haploids were recovered from heterozygous diploids (data not shown). However, as shown in Figure 3B, this truncation can support viability when overexpressed, and to a lesser extent, when expressed in high copy. Thus, the stn11–371 truncation is less functional than the other truncation alleles, indicating that a central domain of Stn1p is inhibitory to the function of the amino-terminal Stn1p fragments.

Figure 5.—

Loss of RAD52 impairs growth, but not telomere length in the stn1-186t strain. (A) Southern blot of stn1-281t, stn1-186t, and stn1-186t rad52-Δ strains (hC671, hC672, hC1110). Genomic DNA was prepared from strains grown in liquid media to saturation, and digested overnight with AluI, HaeIII, HinfI, and MspI. The membrane was probed with [32P]d(GT/CA). (B) Slower growth phenotype of stn1-186t, stn1-281t and stn1-186t rad52-Δ. Strains of the indicated genotypes were streaked out on YPD. The plate was photographed after 2 and 3 days of growth at 30°.

The Stn1p carboxyl terminus is required for negative regulation of telomere length:

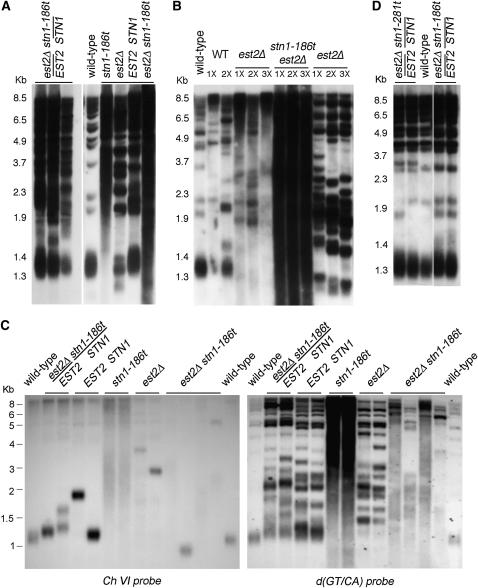

Earlier work has shown that STN1 loss-of-function alleles can display greatly elongated telomere lengths (Grandin et al. 1997), indicating a role in negative regulation of telomerase. It has been proposed that the interaction between Cdc13p and Est1p is responsible for recruitment or activation of Est2p at telomeres while the interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p acts to inhibit telomere lengthening (Grandin et al. 1997; Chandra et al. 2001; Pennock et al. 2001; Taggart et al. 2002; Grossi et al. 2004). On the basis of this model, cells deficient for the Cdc13p–Stn1p interaction would be predicted to have elongated telomeres. Southern blot analysis of telomere length in the stn1-Δ strains overexpressing the Stn1p truncations revealed that telomeres are elongated to varying degrees in each of the strains (Figure 4A). The stn1-Δ/pstn11–371 strains show moderate telomere elongation and the stn1-Δ/pstn11–186 and stn1-Δ/pstn11–281 strains show a more extreme telomere length phenotype, with heterogeneous and significantly elongated telomeres (Figure 4A). While these three stn1 alleles are deficient for Cdc13p association, they display differing extents of telomere elongation. Expressing the stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles from their endogenous locus shows a more extreme telomere length defect. These strains show the most heterogeneous and elongated telomeres, migrating as a broad smear with a lower range of fragments that are at least 1 kb larger than wild-type telomere fragments (Figure 4B). To refine the analysis of the telomere repeat length, the genomic DNA was digested with a combination of four restriction enzymes that each have 4-bp recognition sequences that are not present in the telomere repeats (Teng and Zakian 1999). Southern blotting shows that the TG1–3 repeat restriction fragments in the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains migrate as a heterogeneous smear between ∼1–4 kb in length, as compared to the ∼0.4- and 1-kb terminal fragments observed in wild-type cells (Figure 5A).

Figure 4.—

The interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p contributes to telomere length regulation. For both Southern blots, the genomic DNA was digested with XhoI and the membrane was probed with [32P]d(GT/CA). (A) Southern blot of strains overexpressing the stn1-t alleles (ADH promoter, 2μ) in a stn1-Δ strain (hC567, hC568, hC569). Duplicates are shown for each strain. (B) Southern blot of the integrated stn1-281t and stn1-186t strains, derived from dissection of dCN187 and dCN188.

stn1–281t, but not stn1-186t, requires homologous recombination for viability:

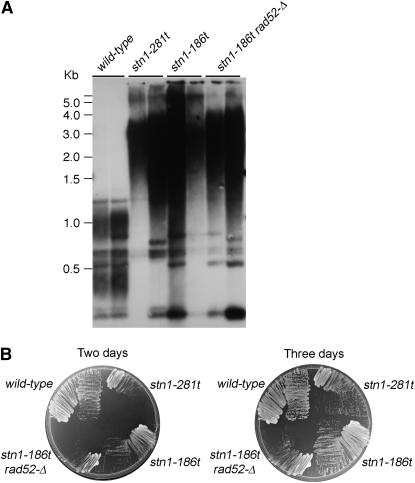

Elongated telomere tracts are typically generated through the activity of telomerase, although homologous recombination can in some cases amplify telomere sequences. Since it has been demonstrated that a mutant allele of the STN1 homolog in Kluyveromyces lactis requires homologous recombination for viability (Iyer et al. 2005), we first used tetrad analysis to test whether RAD52 is essential for growth in either stn1-186t or stn1-281t strains. Interestingly, stn1-281t rad52-Δ haploids were never recovered from heterozygous diploids (23 tetrads dissected), indicating that RAD52 is essential for viability of the stn1-281t strain. In contrast, stn1-186t rad52-Δ haploid cells are viable, but grow more slowly than stn1-186t cells (Figure 5B). Moreover, both stn11–186 and stn11–281 alleles are viable in rad52-Δ strains if they are overexpressed (data not shown). As shown in Figure 5A, the absence of RAD52 does not alter telomere length in stn1-186t rad52-Δ strains, indicating that telomerase is most likely responsible for the extended, heterogeneous telomere lengths.

Telomerase and telomere length are critical for stn1-186t and stn1-281t viability:

To determine whether the telomere elongation in the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains is mediated by telomerase, these strains were crossed with cells deficient for telomerase activity (est2-Δ). However, the analysis of telomere length was precluded because dissection of the resulting diploids produced no viable stn1-281t est2-Δ segregants (of 17 tetrads). Thus, both telomerase and homologous recombination activities are essential for viability of stn1-281t strains. In comparison, the stn1-186t strain shows a severe synthetic phenotype in the absence of EST2; of 21 tetrads dissected from stn1-186t/+ est2-Δ/+ diploids, 22 stn1-186t single mutants, and 10 stn1-186t est2-Δ double mutants were isolated. The stn1-186t est2-Δ colonies on the dissection plate were notably smaller than either the stn1-186t or est2-Δ single mutant (Figure 6A). Further propagation of the stn1-186t est2-Δ cells revealed a synthetic growth defect, with only rare colonies arising on plates (Figure 6B). The telomeres in these few surviving stn1-186t est2-Δ double mutants showed an aberrant structure, with their terminal-restriction fragments migrating as a heterogeneous smear of very short to very long terminal-restriction fragments (Figure 7, A–C). Consistent with these rearranged telomeres being produced by homologous recombination, triple mutant stn1-186t est2-Δ rad52-Δ cells were not recovered in tetrad analysis.

Figure 6.—

Synthetic interaction of stn1-186t with est2-Δ. (A) A dissection plate showing five tetrads that were dissected from a diploid created by mating stn1-186t with est2-Δ (dCN325). The segregation pattern for stn1-186t and stn1-186t est2-Δ is indicated; a square surrounds stn1-186t spores and a circle surrounds the double-mutant spores. (B) Each spore from tetrad 1 shown in (A) was streaked out for single colonies and grown at 30° for 3 days.

Figure 7.—

Diploids inherit elongated telomeres through mating with stn1-186t strains. (A) Southern blot showing telomere lengths in diploids created by mating stn1-186t with est2-Δ (three dCN325 diploid strains shown on the left). The telomere lengths in haploids derived from one of these diploids are shown on the right. The “wild-type” strain is hC160, and was not a progeny of these diploids. Genomic DNA was isolated from cells grown for ∼25 generations and digested with XhoI and probed with [32P]d(GT/CA). (B) Southern blot analysis of telomere length through progressive generations of growth. Haploid est2-Δ, stn1-186t est2-Δ, and wild-type strains that were isolated from the diploids in A were grown for ∼25, 35, and 45 generations prior to genomic DNA isolation. DNA was digested with XhoI and the blot was probed with [32P]d(GT/CA). (C) Analysis of the terminal-telomere fragment from chromosome VI-R in dCN325 diploids (mated) and in haploid progeny from this diploid. The wild-type strains on each end of the blot are hC160. dCN325 has been propagated for ∼30 additional generations in this figure, as compared with the diploids in A. The haploids were propagated for ∼65 generations prior to isolation of DNA. The genomic DNA was digested with XhoI, and the blot was probed with a labeled PCR fragment that hybridizes to a unique telomere proximal sequence on chromosome VI-R (Zubko and Lydall 2006) (left) or with [32P]d(GT/CA) (right). (D) Telomere length in diploids that were created by directly integrating the stn1-186t or stn1-281t allele in an est2-Δ/EST2 diploid (dCN187 and dCN188). Two independent diploids are shown for each strain. DNA was digested with XhoI and probed with [32P]d(GT/CA).

We considered whether the stn1-186t parent contributed elongated telomeres to the stn1-186t/+ est2-Δ/+ diploid, and that this could be a factor affecting the severity of the synthetic phenotype of the stn1-186t est2-Δ haploid strain. This possibility was suggested by the finding that elongated telomere tracts may promote viability in strains deficient for the Ku complex at high temperatures (Gravel and Wellinger 2002). We found that the parent stn1-186t strain did in fact contribute elongated telomeres to the diploid, which were inherited in the haploid progeny, shortening with successive generations in the est2-Δ strains (Figure 7, A and B). Analysis of a single chromosome end confirmed that both the starting diploid and the haploid progeny can show abnormally long telomeres, even in wild-type cells (Figure 7C). Thus, it is possible that the inheritance of some elongated telomeres promotes viability of the stn1-186t est2-Δ haploid strain for several generations. As a test of this hypothesis, the stn1-186t/+ est2-Δ/+ diploid was created by replacing one STN1 allele with the stn1-186t∷kanMX2 cassette in an est2-Δ∷URA3/+ strain. Telomere length in this diploid strain remained similar to wild-type length, indicating that the stn1-186t allele is recessive (Figure 7D). Analysis of 34 tetrads dissected from such diploids showed that while single mutant stn1-186t and est2-Δ spores were easily obtained, only one double mutant stn1-186t est2-Δ spore could be propagated for sufficient generations to confirm its genotype. Thus, the stn1-186t est2-Δ double mutant combination is synthetic lethal when derived from diploid strains with wild-type telomere lengths. However, when the double mutant is derived from diploid strains in which some chromosomes show an elongated telomere structure, it is viable for ∼15–20 generations. These data suggest that the essential function of STN1 is partially compromised in the stn1-281t and stn1-186t strains and the activity of telomerase and, in the case of stn1-281t, homologous recombination, is required to compensate for this defect.

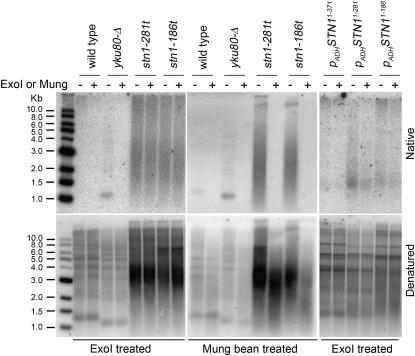

The Stn1p carboxyl terminus has a role maintaining telomere integrity:

Mutant strains such as cdc13-1 and yku80 that have defects in telomere end-protection pathways have been shown to have synthetic growth phenotypes with telomerase-deficient strains (Gravel et al. 1998; Nugent et al. 1998). If either the stn1-186t or the stn1-281t allele is compromised for chromosome capping, then severe growth defects without telomerase would be an expected outcome. To determine whether the carboxyl-terminal domain of Stn1p contributes to its role protecting chromosome ends, the integrity of the telomeres was assessed by an in-gel hybridization procedure (Dionne and Wellinger 1996; Bertuch and Lundblad 2003), probing for the presence of excessive levels of single-stranded TG1–3 sequences. Asynchronous cultures of stn1-186t and stn1-281t displayed a significant amount of single-stranded (ss)TG1–3 in the native gel, as compared to a wild-type strain (data not shown). Because the telomeres in these strains are greatly elongated (Figures 4B and 5A) and single-stranded G overhangs are normally detectable during S phase (Wellinger et al. 1993a,b), it is possible that the signal observed in asynchronous cultures reflects the transient ssTG1–3 present during S phase. Therefore we tested whether the ssTG1–3 was present in G1, when the G overhang is too short to be detected in wild-type cells but is detectable in yku80-Δ cells (Gravel et al. 1998; Polotnianka et al. 1998). We found that the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains both show significant levels of ssTG1–3 in G1 arrested cells, indicating that the integrity of the telomeres is indeed disrupted in these strains (Figure 8). To determine if the G-rich single-stranded signal is a 3′ overhang at the telomere terminus, the DNA was digested with ExoI, a nuclease that initiates its nucleolytic digestion from 3′ DNA ends, prior to digestion with XhoI and analysis of the telomere restriction fragments. While the ssTG1–3 signal in yku80-Δ strains is sensitive to ExoI activity (Gravel et al. 1998; Polotnianka et al. 1998), the ssTG1–3 signal in the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains was not reduced by the ExoI treatment, even after extended incubation times (Figure 8). In contrast, we found that the ssTG1–3 present in these strains is sensitive to a single-strand DNA endonuclease; incubation with mung bean nuclease completely digests the ssTG1–3 in these strains (Figure 8). This indicates that the single-stranded regions in these stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains are likely to be single-strand gaps rather than terminal extensions, and thus are structurally distinct from the ssTG1–3 detected in cdc13-5, yku80-Δ, or pol1-17 cells (Gravel et al. 1998; Adams Martin et al. 2000; Chandra et al. 2001). Such internal single-strand telomere sequences have been detected in both “type II” telomerase-deficient strains that survive senescence by employing a RAD52- and RAD50-dependent recombination pathway to maintain telomere function (Larrivee and Wellinger 2006). They have also been detected to some extent in the K. lactis stn1-M1 mutant strain (Iyer et al. 2005). The type II survivor cells amplify their TG1–3 telomere repeat sequences such that their terminal restriction fragments typically migrate on a Southern blot as a mix of distinct fragments. In contrast, in the stn1-186t, stn1-281t, and in the K. lactis stn1-M1 strains (Iyer et al. 2005), telomerase is active and, in the case of the stn1-186t cells, sufficient for telomeres to appear as a heterogeneous smear. Thus, the loss of telomere integrity observed in the stn1-t strains has characteristics that distinguish it in comparison with other mutant strains that show end-protection defects.

Figure 8.—

stn1-t alleles show unusual telomere integrity defect when expressed from the endogenous locus. In-gel hybridization assay to test for presence of ssTG1–3 DNA in stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains, or in stn1-Δ strains overexpressing STN1 residues 1–186, 1–281, or 1–371 (hC567, hC568, and hC569). Wild-type and yku80-Δ strains are shown as controls. Genomic DNA was prepared from cells that were grown at 30° to an OD600 ∼ 1 and arrested in G1 by α-factor. Samples were split and mock treated or digested with either ExoI or mung bean nuclease. All samples were then digested with XhoI and analyzed by in-gel hybridization as previously described (Bertuch and Lundblad 2003). The top gel (native) shows the detection of single-stranded TG1–3 by the labeled telomere CA probe. The total TG1–3 signal is detected in the bottom gel (denatured), following denaturation and reprobing of the native gel.

Overexpressing the stn1-t alleles largely restores more typical telomere structure. As shown in Figure 8, the integrity of telomeres in G1 arrested stn1-Δ strains overexpressing the stn11–186 or stn11–371 allele is not significantly disrupted. However, in the stn11–281 strain, telomeres do show increased levels of single-stranded TG1–3 that now appear to be predominantly terminal overhangs, as the signal is largely sensitive to digestion by ExoI.

Checkpoint responses remain proficient in stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains:

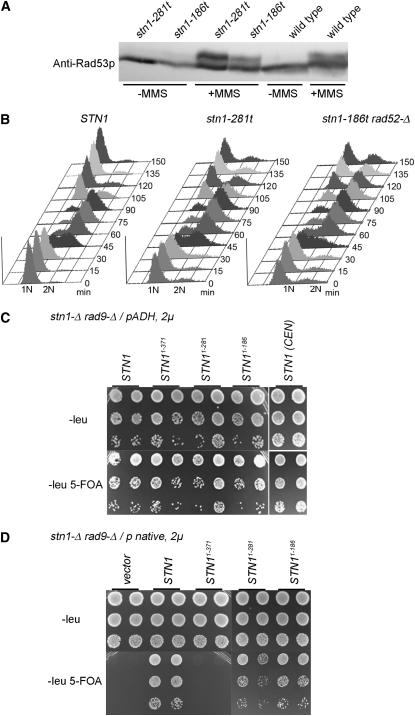

The DNA damage checkpoint is quite sensitive to the single-stranded TG1–3 lesions exposed in cdc13-1 cells at restrictive temperature, being activated by sublethal levels of DNA damage in these cells (Weinert and Hartwell 1993; Garvik et al. 1995). On the other hand, the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains are viable, despite observable defects in telomere integrity. This suggests either that their telomere damage is not detected by the DNA damage checkpoint or that the cells are initially arrested by the checkpoint but adapt to or recover from the checkpoint to continue proliferation. To investigate the checkpoint response, the phosphorylation status of Rad53, a central kinase in the DNA damage checkpoint, was determined. As previously shown, inactivation of cdc13-1 results in a robust shift of Rad53p to a slower-migrating, phosphorylated isoform (Grandin et al. 2005; Petreaca et al. 2006). However, in both the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains, the Rad53 protein does not show a shift in mobility (Figure 9A), consistent with the proliferation of the strains. These strains do remain proficient for checkpoint signaling through Rad53p, as shown by the significant shift of Rad53p to a slower migrating isoform upon exposure to MMS (Figure 9A). Therefore, these cells have not shut off the DNA damage checkpoint to continue proliferation. We analyzed the ability of single cells isolated from a logarithmically growing culture to form colonies. The overall plating efficiency for both strains was reduced compared with wild-type cells, such that ∼87% of stn1-281t and 92% of stn1-186t cells form colonies. In both strains, most of the cells that do not form colonies arrest growth as microcolonies containing fewer than 10 cell bodies. These microcolonies did not form viable colonies following several days of incubation at 30°, potentially indicating the presence of lethal levels of DNA damage. To determine if the mutant strains activate the DNA damage checkpoint each cell cycle, the DNA content of a population of cells was measured by FACS as the cells move through one cell cycle, initially synchronized in G1. Both the stn1-186t rad52-Δ and stn1-281t strains show a transient cell-cycle delay between the apparent completion of S phase and their subsequent reentry to G1 (Figure 9B). The cell-cycle delay observed in the stn1-186t rad52-Δ and stn1-281t strains could potentially reflect transient checkpoint activation.

Figure 9.—

The DNA damage checkpoint is required for stn1-t viability. (A) Rad53p phosphorylation in stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains. Asynchronously growing strains were split in half, with one portion treated with 0.1% MMS for 2.5 hr. All samples were lysed in 20% TCA, and equal amounts of each lysate were loaded and separated on a 10% 30:0.39 acrylamide:bisacrylamide gel. The Western blot was probed with an anti-Rad53p antibody. (B) FACS analysis of a synchronized cell cycle in wild-type, stn1-186t rad52-Δ, and stn1-281t strains. Cell-cycle progression was measured for 150 min following release from a G1 arrest, with the cells rearresting in G1 due to addition of α-factor during the release period. (C) Viability of the overexpressed stn1-t alleles (ADH, 2μ) in the stn1-Δ rad9-Δ background. A stn1-Δ rad9-Δ/pVL1046 (pSTN1 on a CEN-URA3 plasmid) strain (hC1577) was transformed with the pCN181, pCN234, pCN235, pCN249, pACT2.2, or pCN1 plasmids; liquid cultures of these transformants were grown at 30°. Serial 10-fold dilutions of the cultures were plated on −Leu or −Leu 5-FOA, and incubated at 30° for 3 days. (D) Viability of the stn1 truncations expressed from the STN1 promoter on 2μ plasmids in the stn1-Δ rad9-Δ background (plasmids pCN318, pCN319, pCN320, pVL1066, and YEplac181, transformed into hC1577). Strains were manipulated as in C.

DNA damage checkpoint is essential in stn1-t strains expressed at lowest viable levels:

To determine whether the DNA damage checkpoint is indeed required for this cell-cycle delay, we first attempted to construct stn1-186t strains that were deficient for the DNA damage checkpoint. However, the stn1-186t allele was not recovered as a double mutant in combination with either rad9 or rad24 checkpoint deficient alleles, following dissection of 31 tetrads and 22 tetrads, respectively. Thus, the DNA damage checkpoint is essential for stn1-t viability. This is distinct from cdc13-1 strains, where the DNA damage checkpoint arrests the cell cycle in the presence of sublethal levels of DNA damage (Weinert and Hartwell 1993; Garvik et al. 1995). Since the dosage of the stn1-t alleles is a variable that alters their phenotype, we next determined whether the DNA damage checkpoint is required for the viability of stn1-Δ strains that express the stn1-t alleles at higher levels. Specifically, we tested the viability of the alleles in rad9-Δ cells when produced from either overexpression or high-copy plasmids. All three stn1-t alleles were viable in the absence of rad9-Δ when overproduced as the two-hybrid constructs (Figure 9C). The stn11–186 and stn11–281 strains were also viable without the DNA damage checkpoint when expressed from its native promoter on a high-copy plasmid (Figure 9D). Therefore, RAD9 is an essential requirement for the stn11–186 and stn11–281 strains only when the alleles are expressed at levels presumably nearing endogenous STN1. The checkpoint requirement correlates with the presence of increased levels of ssTG1–3 present in the integrated stn1-t strains (Figure 8), indicating that the dosage of the stn1-t alleles influences the cells' ability to maintain telomere capping.

DISCUSSION

We undertook this study to determine whether the role of Stn1p promoting telomere integrity and proper telomere length could be attributed to physical interaction with either the single-strand telomere binding protein Cdc13p or with Ten1p. A summary of the results obtained is presented in Table 3. Our analysis of the interactions of Stn1p with Cdc13p and Ten1p indicate that the Stn1p amino terminus is necessary and sufficient for interaction with Ten1p and the Stn1p carboxyl terminus is necessary and sufficient for interaction with Cdc13p. Although we were unable to confirm our two-hybrid analysis of the Stn1p–Cdc13p interaction by an independent biochemical method, the observation that each construct remains proficient for interaction with at least one partner greatly strengthens the conclusion that the lack of interaction with the other partner reflects a disrupted-protein association. Further analysis of the Stn1p–Cdc13p complex to determine whether these proteins form a stable or transient association during the cell cycle would be of great interest.

TABLE 3.

Summary of stn1 truncation allele phenotypes

| Growth | Telomere lengthb (kb) | ssTG telomere | Rad53p shift | With rad9-Δ | With rad52-Δ | With est2-Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stn1-186t | Viable, slow growth | +0.5–4.0 | Increased, ExoI resistant | Not detected | Dead | Viable, slow growth | Severe synthetic |

| STN11–186a | Viable | +0.3–3.0 | Small increase, ExoI sensitive | Not detectedc | Viable | Viabledc | NT |

| stn1-281t | Viable, slow growth | +0.5–4.0 | Increased, ExoI resistant | Not detected | Dead | Synthetic lethal | Synthetic lethal |

| STN11–281a | Viable | +0.3–3.0 | Increased, ExoI sensitive | Barely detectedc | Viable | Viabledc | NT |

| stn1-371t | Dead | NA | NA | NA | NT | NT | NT |

| STN11–371a | Viable | +0.3–1.2 kb | Not increased | Barely detectedc | Viable | Viabledc | NT |

NT, not tested; NA, not applicable (due to strain inviability).

These alleles are fused with the Gal4 DNA activation domain and HA-epitope and are expressed under the ADH promoter on 2μ plasmids in stn1-Δ strains.

Approximate increase in the range of telomere length as compared with wild-type telomeres.

Data not shown.

Tested by plating rad52-Δ stn1-Δ + pVL1046, pADHstn1 (pCN249, pCN234, or pCN235) on 5-FOA.

One important conclusion arising from our analysis of stn1 alleles that fail to interact with Cdc13p is that they are able to complement the stn1 null and can be viable at endogenous levels. On the other hand, the stn1 alleles that lack the amino-terminal region of Stn1p and fail to interact with Ten1p are not able to complement the stn1 null. These observations allow us to conclude that (1) the Stn1p amino-terminal 186 residues are critical for the essential function of Stn1p, and (2) the carboxyl terminus, and thus presumably, the interaction between Stn1p and Cdc13p, are less important for viability.

Interestingly, while Stn1p residues 1–186 are necessary and sufficient for viability at all expression levels, adding residues up to 371 significantly reduces its ability to complement the stn1-Δ, particularly at low dosage. The inclusion of this region may alter the folding or levels of the mutant Stn1-t protein, although our data comparing steady-state protein levels of the overexpressed constructs do not show a relative reduction in protein levels for the stn11–371 construct (Figure 2B). Alternatively, forms of Stn1p that include residues 281–371 may actually interfere with essential aspects of Stn1p function by being able to participate in a wider range of nonessential interactions or activities or by preventing its appropriate function within complexes. For example, this region may encode a regulatory domain, such as a site of negative regulatory post-translational modification.

In budding yeast, Cdc13p is considered a key factor protecting chromosome ends from degradation (Garvik et al. 1995; Diede and Gottschling 1999; Vodenicharov and Wellinger 2006) or illegitimate recombination (Dubois et al. 2002). The pair-wise two-hybrid interactions between Cdc13p, Stn1p, and Ten1p have led to the expectation that Cdc13p would mediate its role in end protection by forming a complex with Stn1p and Ten1p and that destabilization of any component of this complex would cause a loss of telomere integrity. It has been assumed that Stn1p function in telomere protection would be mediated through a direct physical interaction with Cdc13p. However, the data presented here are not consistent with this model, indicating the interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p is neither essential for chromosome capping nor the only means through which Stn1p exerts regulation of telomere length. This is not to suggest that the interaction between Cdc13p and Stn1p is not important, but rather that the interactions of Stn1p with additional proteins that perform critical functions at telomeres may provide partial compensation for the defect in the Cdc13p–Stn1p interaction. For example, Stn1p interacts with Ten1p, and Ten1p can interact with Cdc13p. If interaction between Cdc13p and Ten1p is direct, then it is possible that a heterotrimeric complex can form that includes the truncated Stn1p, with Ten1p bridging the interaction between Cdc13p and Stn11–186p. Furthermore, the function or stability of such a putative complex may be affected by which region of the Stn1p carboxyl terminus is present (as when the 281–371 domain is present, for example). Therefore, from our data it is still possible that Cdc13, Stn1, and Ten1 proteins function as one complex to promote both telomere capping and length regulation. To address this point, further experiments are necessary to determine if the Cdc13p–Ten1p interaction is essential in the absence of the Cdc13p–Stn1p interaction and whether these interactions are essential for telomere localization of Stn1p and Ten1p.

stn1-t alleles show defects in chromosome capping when expressed from the endogenous locus:

Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that the interaction between Stn1p and Cdc13p contributes to chromosome end protection. Specifically, the findings that the stn11–371 allele is not viable unless it is overexpressed, and the integrated stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles show deficiencies indicating compromised telomere integrity. In parallel with the capping deficient cdc13-1 and yku80-Δ strains (Nugent et al. 1998), the stn1-186t and stn1-281t alleles show severe synthetic growth defects in the absence of telomerase (est2-Δ). However, it should be noted that the deficiencies in these stn1-t strains are distinct in several ways from those observed in cdc13-1 strains. First, the single-stranded telomere DNA in the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains is present as internal gaps within the telomere sequence, rather than as a terminal overhang. Second, in cdc13-1 cells, the DNA damage checkpoint is activated by sublethal levels of DNA damage, as evidenced by the increase in the maximum permissive temperature of cdc13-1 strains when the cells are also deficient for checkpoint function (from ∼25°–26° up to ∼28° in rad9Δ strains) (Weinert and Hartwell 1993). In contrast, a functional DNA damage checkpoint is essential for viability of the stn1-186t and stn1-281t strains. This difference may indicate that the stn1-t strains require only a transient checkpoint delay to complete telomere replication or to repair telomeric damage such that it is below a threshold recognized by the checkpoint, prior to entering mitosis. Finally, the stn1-281t strain requires RAD52 for viability, suggesting homologous recombination is essential to maintain functional telomeres in this strain. One way to interpret these observations is that Stn1p and Cdc13p make independent contributions to telomere capping. Thus, in stn1-t strains, Cdc13p is still present and capable of binding telomere DNA. This binding may provide an essential, albeit weakened, level of capping activity that allows stn1-t strains to remain viable and proceed through the cell cycle. In support of this contention, we have observed that stn1-t cdc13-1 strains exhibit synthetic lethality, indicating a critical role for Cdc13p in stn1-t cell survival (C. Nugent, unpublished observation). If correct, this model predicts Cdc13p must remain capable of providing some end-protection functions despite impaired interaction with the truncated Stn1 protein, reinforcing the conclusion that the role of Cdc13p in end protection is not simply mediated through an Stn1p–Cdc13p interaction.

The mechanism by which the single-stranded gaps are created in the stn1-t strains remains to be determined. One possibility is that the replication of the lagging telomere strand may be compromised such that single-strand gaps are produced. Alternatively, long terminal single-strand regions could have initially been created by nuclease resection, with subsequent partial repair or fill-in synthesis that produces single-strand gaps. We found that these deficiencies are observed only when the stn1 truncation alleles are expressed from the endogenous STN1 locus. Higher stn1-t dosage can support telomere capping, although strains overexpressing stn11–281 show some detectable single-stranded TG1–3. The level of protein produced from the integrated stn1-t alleles may not be equivalent to the normal Stn1 protein levels; in this case the stn1-t integrity defects could be related to insufficient levels of the Stn1p essential region.

The Stn1 C terminus has an important role negatively regulating telomere length:

Consistent with the hypothesis that interaction between Stn1p and Cdc13p is required for normal telomere length regulation, we observed elongated telomeres in all stn1-t alleles that we examined. However, the extent of telomere lengthening differed among these alleles, with the stn11–186 and stn11–281 alleles showing a more severe phenotype than the stn11–371 allele, even though all fail to interact with Cdc13p in the two-hybrid assay. Reducing the level of stn11–186 or stn11–281 expression exacerbated the elongation of telomeres. Therefore, interaction with Cdc13p is not the only determinant of telomere lengthening for stn1-t alleles. Stn1p must contribute to telomere regulation independent of, or in addition to, its interaction with Cdc13p.

The elongated telomere length in these stn1-t mutants is consistent with previous data that indicated Stn1p acts as a negative regulator of telomere extension (Grandin et al. 1997). Two models have been proposed for how Stn1p mediates this function. First, its interaction with Cdc13p could lead to inhibition of telomerase activity, possibly through an effect upon the Cdc13p–Est1p interaction (Grandin et al. 2000; Pennock et al. 2001). Cdc13p has been proposed to activate telomerase activity through Est1p, potentially by recruiting Est1p to telomeres (Pennock et al. 2001; Taggart et al. 2002). Second, Stn1p could influence telomere length through its contacts with Pol12p, a regulatory subunit of the polymerase-α primase complex (Foiani et al. 1994; Grossi et al. 2004). Thus, Stn1p could facilitate the activity of the polymerase-α primase complex at telomeres, particularly following telomere extension by telomerase (Grossi et al. 2004). Since synthesis of the telomere C strand by the DNA replication machinery appears to negatively regulate telomere length, it has been postulated that the extension of telomere repeats by telomerase is coordinated with the fill-in synthesis by the replication machinery (Price 1997; Chakhparonian and Wellinger 2003). We have shown that Stn11–186p retains the ability to interact with Pol12p in pull-down assays done both in vivo and in vitro (Petreaca et al. 2006), indicating that this interaction is likely retained in stn1-t strains. At the same time, additional regions within the carboxyl terminus of Stn1p can contribute to interaction with Pol12p (Grossi et al. 2004; Petreaca et al. 2006). Thus, it is possible that the interaction between Stn1p and Pol12p is differentially affected in the various stn1-t strains, potentially providing a rationale for their varying phenotypic severity.

In summary, the carboxy terminus of Stn1p is not essential for cell viability but nonetheless makes important contributions to telomere-length regulation and to telomere integrity, potentially through interaction with Cdc13p. Our data establish that the essential function of STN1 resides in the amino terminus of the protein, a region that is competent for interaction with Ten1p and Pol12p, but not with Cdc13p. The dosage of the stn1-t alleles differentially affects the telomere integrity as well as telomere length in the mutant strains. To explain these observations, we propose that multiple interactions among telomere binding proteins allow redundancy in telomere end protection and replication mechanisms, providing robust pathways for maintenance of telomere function.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Elledge and V. Lundblad for strains and plasmids. Critical comments from J. Bachant and discussion with lab members are greatly appreciated. This project was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA96972).

References

- Adams, A. K., and C. Holm, 1996. Specific DNA replication mutations affect telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 4614–4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams Martin, A., I. Dionne, R. J. Wellinger and C. Holm, 2000. The function of DNA polymerase alpha at telomeric G tails is important for telomere homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 786–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- As, I. J., and C. W. Greider, 2003. Short telomeres induce a DNA damage response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 987–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachant, J., A. Alcasabas, Y. Blat, N. Kleckner and S. J. Elledge, 2002. The SUMO-1 isopeptidase Smt4 is linked to centromeric cohesion through SUMO-1 modification of DNA topoisomerase II. Mol. Cell 9: 1169–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuch, A. A., and V. Lundblad, 2003. The Ku heterodimer performs separable activities at double-strand breaks and chromosome termini. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 8202–8215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, E. H., 2000. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature 408: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, E. H., 2001. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106: 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakhparonian, M., and R. J. Wellinger, 2003. Telomere maintenance and DNA replication: How closely are these two connected? Trends Genet. 19: 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A., T. R. Hughes, C. I. Nugent and V. Lundblad, 2001. Cdc13 both positively and negatively regulates telomere replication. Genes Dev. 15: 404–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlseid, J. N., J. Lew-Smith, M. J. Lelivelt, S. Enomoto, A. Ford et al., 2003. mRNAs encoding telomerase components and regulators are controlled by UPF genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2: 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, T., 2005. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 19: 2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diede, S. J., and D. E. Gottschling, 1999. Telomerase-mediated telomere addition in vivo requires DNA primase and DNA polymerases alpha and delta. Cell 99: 723–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne, I., and R. J. Wellinger, 1996. Cell cycle-regulated generation of single-stranded G-rich DNA in the absence of telomerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 13902–13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, M. L., Z. W. Haimberger, M. W. McIntosh and D. E. Gottschling, 2002. A quantitative assay for telomere protection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 161: 995–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S. K., and V. Lundblad, 1999. Est1 and Cdc13 as comediators of telomerase access. Science 286: 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X., and C. M. Price, 1997. Coordinate regulation of G- and C-strand length during new telomere synthesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 8: 2145–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foiani, M., F. Marini, D. Gamba, G. Lucchini and P. Plevani, 1994. The B subunit of the DNA polymerase alpha-primase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae executes an essential function at the initial stage of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 923–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H., R. B. Cervantes, E. L. Mandell, J. H. Otero and V. Lundblad, 2007. RPA-like proteins mediate yeast telomere fuction. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14: 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik, B., M. Carson and L. Hartwell, 1995. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 6128–6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gire, V., 2004. Dysfunctional telomeres at senescence signal cell cycle arrest via Chk2. Cell Cycle 3: 1217–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, N., A. Bailly and M. Charbonneau, 2005. Activation of Mrc1, a mediator of the replication checkpoint, by telomere erosion. Biol. Cell 97: 799–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, N., C. Damon and M. Charbonneau, 2000. Cdc13 cooperates with the yeast Ku proteins and Stn1 to regulate telomerase recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 8397–8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, N., C. Damon and M. Charbonneau, 2001. Ten1 functions in telomere end protection and length regulation in association with Stn1 and Cdc13. EMBO J. 20: 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, N., S. I. Reed and M. Charbonneau, 1997. Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13. Genes Dev. 11: 512–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel, S., M. Larrivee, P. Labrecque and R. J. Wellinger, 1998. Yeast Ku as a regulator of chromosomal DNA end structure. Science 280: 741–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel, S., and R. J. Wellinger, 2002. Maintenance of double-stranded telomeric repeats as the critical determinant for cell viability in yeast cells lacking Ku. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 2182–2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, S., A. Puglisi, P. V. Dmitriev, M. Lopes and D. Shore, 2004. Pol12, the B subunit of DNA polymerase alpha, functions in both telomere capping and length regulation. Genes Dev. 18: 992–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S., A. D. Chadha and M. J. McEachern, 2005. A mutation in the STN1 gene triggers an alternative lengthening of telomere-like runaway recombinational telomere elongation and rapid deletion in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 8064–8073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, P., J. Halladay and E. A. Craig, 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144: 1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrivee, M., and R. J. Wellinger, 2006. Telomerase- and capping-independent yeast survivors with alternate telomere states. Nat. Cell Biol. 8: 741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendvay, T. S., D. K. Morris, J. Sah, B. Balasubramanian and V. Lundblad, 1996. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics 144: 1399–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. J., and V. A. Zakian, 1996. The Saccharomyces CDC13 protein is a single-strand TG1–3 telomeric DNA-binding protein in vitro that affects telomere behavior in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 13760–13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad, V., and J. W. Szostak, 1989. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell 57: 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig, A. J., 2001. Cdc13 subcomplexes regulate multiple telomere functions. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8: 297–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall, D., and T. Weinert, 1995. Yeast checkpoint genes in DNA damage processing: implications for repair and arrest. Science 270: 1488–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, C. I., G. Bosco, L. O. Ross, S. K. Evans, A. P. Salinger et al., 1998. Telomere maintenance is dependent on activities required for end repair of double-strand breaks. Curr. Biol. 8: 657–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, C. I., T. R. Hughes, N. F. Lue and V. Lundblad, 1996. Cdc13p: a single-strand telomeric DNA-binding protein with a dual role in yeast telomere maintenance. Science 274: 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock, E., K. Buckley and V. Lundblad, 2001. Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell 104: 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petreaca, R. C., H. C. Chiu, H. A. Eckelhoefer, C. Chuang, L. Xu et al., 2006. Chromosome end protection plasticity revealed by Stn1p and Ten1p bypass of Cdc13p. Nat. Cell Biol. 8: 748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polotnianka, R. M., J. Li and A. J. Lustig, 1998. The yeast Ku heterodimer is essential for protection of the telomere against nucleolytic and recombinational activities. Curr. Biol. 8: 831–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, C. M., 1997. Synthesis of the telomeric C-strand. A review. Biochemistry Mosc. 62: 1216–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H., and V. A. Zakian, 2000. The Saccharomyces telomere-binding protein Cdc13p interacts with both the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase alpha and the telomerase-associated Est1 protein. Genes Dev. 14: 1777–1788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, Y., B. A. Desany, W. J. Jones, Q. Liu, B. Wang et al., 1996. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science 271: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]