Abstract

The mitotic spindle is a complex and dynamic structure. Genetic analysis in budding yeast has identified two sets of kinesin-like motors, Cin8p and Kip1p, and Kar3p and Kip3p, that have overlapping functions in mitosis. We have studied the role of three of these motors by video microscopy of motor mutants whose microtubules and centromeres were marked with green fluorescent protein. Despite their functional overlap, each motor mutant has a specific defect in mitosis: cin8Δ mutants lack the rapid phase of anaphase B, kip1Δ mutants show defects in the slow phase of anaphase B, and kip3Δ mutants prolong the duration of anaphase to the point at which the spindle becomes longer than the cell. The kip3Δ and kip1Δ mutants affect the duration of anaphase, but cin8Δ does not.

Keywords: mitosis, kinesin, microtubule, anaphase, yeast

The mitotic spindle segregates the chromosomes into the daughter cells during cell division. The dynamic behavior of the spindle is controlled by motor proteins that move along microtubules and by the polymerization and depolymerization of microtubules. Motor proteins are required to assemble and maintain a bipolar spindle, to regulate microtubule dynamics, and to orient the spindle in the cell. After the spindle has formed, motor proteins mediate spindle elongation and chromosome separation during anaphase (reviewed in McIntosh and Pfarr, 1991; Inoue and Salmon, 1995; Vernos and Karsenti, 1996).

In vertebrate cells, the roles of motor proteins have been dissected by inactivating motors in living cells and egg extracts (Rodionov et al., 1993; Vaisberg et al., 1993; Lombillo et al., 1995; Walczak et al., 1996; Heald et al., 1997). These approaches are powerful, but can produce complex results because many motors have overlapping functions and antibody inactivation or immunodepletion experiments can also affect proteins that interact with the target motor protein. Budding yeast is an attractive alternative for studying the roles of specific motors in mitosis: the genome sequence (Goffeau et al., 1996) provides a complete inventory of microtubule motors, yeast genetics allows inactivation of individual motors, and marking centromeres and microtubules with green fluorescent protein (GFP) makes it possible to study spindle and chromosome dynamics in living cells (Straight et al., 1997). Yeast contain six kinesin related proteins (Cin8p, Kar3p, Kip1p, Kip2p, Kip3p, and Smy1p) and a single dynein (Meluh and Rose, 1990; Hoyt et al., 1992; Lillie and Brown, 1992; Roof et al., 1992; Eshel et al., 1993; Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). This paper analyzes the mitotic roles of three of the six kinesin motors: Cin8p, Kip1p and Kip3p. We did not study Smy1p since it doesn't appear to be involved in mitosis (Lillie and Brown, 1992, 1994) or Kip2p because it primarily affects cytoplasmic microtubules rather than the intranuclear microtubules of the mitotic spindle (Huyett et al., 1998). We were unable to study kar3Δ mutants, because most cells arrest in mitosis under the conditions required for microscopy.

Cin8p and Kip1p kinesins belong to the bimC/Cut7 class of microtubule motors that have roles in spindle formation and spindle elongation in other organisms (reviewed in Kashina et al., 1997). Kip3p, is a novel kinesin that does not easily fit into the known kinesin subfamilies but has been shown to be important for spindle positioning (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). The minus end–directed motor Kar3p antagonizes the activity of Cin8p/Kip1p to ensure proper spindle assembly and elongation (Saunders and Hoyt, 1992; Saunders et al., 1997) and is also thought to participate in the positioning of the spindle (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). In addition to the kinesin family of proteins, dynein also has roles in spindle positioning, assembly and elongation (Li et al., 1993; Vaisberg et al., 1993; Saunders et al., 1995; Yeh et al., 1995; Carminati and Stearns, 1997; Heald et al., 1997; Shaw et al., 1997).

The Cin8p and Kip1p proteins are thought to be plus end directed motors that have overlapping roles in pushing the spindle pole bodies apart. cin8 was isolated as a mutant that exhibited elevated chromosome loss (Hoyt et al., 1990). At 37°C cin8Δ mutants arrest in mitosis with duplicated spindle poles but fail to form a bipolar spindle. The defect in cin8Δ mutants can be overcome by mild overexpression of Kip1p, suggesting that the two motors have redundant functions during mitosis (Hoyt et al., 1992). Furthermore, cin8Δ kip1Δ double mutants are inviable and fail to form a bipolar spindle (Hoyt et al., 1992; Roof et al., 1992). Cin8 and Kip1 are required for both assembly and maintenance of the bipolar spindle: bipolar spindles in kip1Δ cells that carry a temperature sensitive allele of cin8 collapse when cells are shifted to the nonpermissive temperature. This collapse is partially rescued in cells lacking Kar3p, suggesting that the length of the spindle is controlled by the balance between forces generated by Cin8p and Kip1p that push the spindle pole bodies apart and those generated by Kar3p that pull them together (Saunders and Hoyt, 1992).

Kip3p plays a role in the migration of the nucleus to the neck between the mother and daughter cells and the proper alignment of the mitotic spindle before anaphase (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). One explanation for these roles is that Kip3p, like certain other motors (Endow et al., 1994; Walczak et al., 1996), can destabilize microtubules.

Since the spindle is a dynamic structure, we investigated its behavior by time lapse microscopy of wild-type and mutant cells whose centromeres and microtubules were marked with GFP. Kip1p and Cin8p have distinct roles during anaphase chromosome separation and spindle elongation. Although both motors are required for normal elongation of the spindle, Cin8p is most important early in anaphase when rapid separation of the chromosomes occurs, and Kip1p is required late in anaphase for robust elongation of the spindle. Analysis of Kip3p mutants shows that Kip3p does not play a role in the absolute rates of anaphase spindle elongation but is involved in the proper timing of spindle disassembly. Thus, despite the functional overlap between them, each of the three kinesin motors contributes to a particular event during anaphase.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Media

Yeast were grown either in YPD (10 g/liter yeast extract, 20 g/liter Bacto-Peptone, 20 g/liter Dextrose) supplemented with 50 mg/liter adenine-HCl, and 50 mg/liter l-tryptophan or in complete synthetic medium lacking histidine (CSM-HIS; Sherman et al., 1974) supplemented with 50 mg/liter adenine-HCl, 50 mg/liter l-tryptophan, and 6.5 g/liter NaCitrate. Yeast strains are listed in Table I and are all isogenic to W303 (AFS34). Yeast transformations were performed using the lithium acetate method (Ito et al., 1983). Plasmids were propagated in Escherichia coli strain TG1 (Sambrook et al., 1989) in medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin except for Lac operator repeat plasmids which were propagated in E. coli STBL2 (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). GFP-Lac repressor and GFP-Tubulin fusions were induced as described (Straight et al., 1996, 1997).

Table I.

Yeast Strains

| Strain number | Relevant genotype | Plasmid | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFS34 (W303-1a) | MATa ade2-1 can1-100 ura3-1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 trp1-1 | |||

| AFS403 | MATa his3-11,15::GFP-LacI-HIS3 leu2-3,112::lacO-LEU2 ura3-1::GFP-TUB1-URA3 | pAFS78 | ||

| pAFS59 | ||||

| pAFS91 | ||||

| AFS426 | MATa cin8Δ::TRP1 his3-11,15::GFP-LacI-HIS3 leu2-3,112::lacO-LEU2 ura3-1::GFP-TUB1-URA3 | " | ||

| AFS404 | MATa kip1Δ::HIS3 his3-11,15::GFP-LacI-HIS3 leu2-3,112::lacO-LEU2 ura3-1::GFP-TUB1-URA3 | " | ||

| AFS417 | MATa kip3Δ::HIS3 his3-11,15::GFP-LacI-HIS3 leu2-3,112::lacO-LEU2 ura3-1::GFP-TUB1-URA3 | " | ||

| AFS501 | MATa his3-11,15::GFP13-LacI-I12-HIS3 leu2-3,112::lacO-LEU2 ura3-1::GFP-TUB1-URA3 | pAFS144 | ||

| pAFS59 | ||||

| pAFS91 |

All strains are isogenic to AFS34 (W303-1a from the laboratory of R. Rothstein). Only the genotype that differs from AFS34 is shown.

Plasmids and DNA Manipulation

Construction of Motor Protein Deletions.

The cin8Δ::LEU2 deletion plasmid was provided by Andrew Hoyt (Hoyt et al., 1992). CIN8 was deleted in strain AFS34, then the LEU2 marked CIN8 deletion was changed to TRP1 by integrating the marker switching plasmid pLT7 from F. Cross (Cross, 1997).

Kip1 was amplified from yeast genomic DNA by PCR using the following oligonucleotide pair: 5′-GCTTGGTCGACGTCAAATGCAGACGGATACGAG-3′; 5′-GCCAATTCGTATGGTGCTGCGGCCGTCAAC-3′. The PCR product was digested with SalI and EagI and cloned into SalI- and EagI-digested pBluescript (KS−; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to yield pAFS108. The complete open reading frame of KIP1 was replaced by inserting an EcoRI-SphI fragment of HIS3 into EcoRI-SphI–digested pAFS108. The resulting deletion construct pAFS111 was digested with NotI and AatII and transformed into yeast strain AFS34.

KIP3 was amplified from yeast genomic DNA by PCR using the following oligonucleotide pair: 5′-GCGCTCGAGAACTGAACGTCATAGTTATAG-3′; 5′-ACGTTATTCCTCCTCCTGTTCGCGGCCGCGCGC-3′. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and NotI and cloned into XhoI- and NotI-digested pBluescript (KS−; Stratagene) to yield pAFS119. The NheI-HincII fragment of pAFS119 was replaced with an XbaI-SmaI fragment of HIS3 to remove the open reading frame of KIP3. The deletion plasmid pAFS124 was then cut with EcoRV and NotI and transformed into yeast strain AFS34.

Mutagenesis of GFP-LacI Fusions.

GFP was fused to the Lac repressor as previously described (Straight et al., 1996). The Ser65→ Thr mutant of GFP (Heim and Tsien, 1996) was linked with XhoI and HindIII sites by PCR using the following oligonucleotide pair: 5′-CGCCTCGAGGAGATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT-3′; 5′-GGCATGGATGAACTATACAAATAAGCTTCGC-3′. The XhoI-HindIII–digested PCR product was cloned into SalI-HindIII–digested pQE9 (QIAGEN, Inc., Chatsworth, CA) to generate a 6-histidine fusion to GFP (pAFS97). Mutant GFP molecules were generated by PCR shuffling (Stemmer, 1994), expressed in E. coli at 37°C then sorted by Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting to isolate cells that fluoresced strongly at 37°C. These mutant GFP molecules were then screened for fluorescence intensity relative to the Ser65→ Thr mutant of GFP and the brightest molecule was sequenced. The brightest GFP (GFP12) was mutated at codon 163 from GTT to GCT changing Val163 to Ala163. This change resulted in the same amino acid change described by Siemering et al. (1996) for the GFP-B mutant but used a different codon. Based on the work of Siemering et. al we then combined our GFP12 mutant with the Ser175→ Gly mutation to give GFP13 (S65T, V163A, and S175G).

Certain mutations in the lac repressor cause increased affinity between the repressor and operator DNA (Miller and Reznikoff, 1980). We mutated the GFP-lac repressor fusion contained in pAFS78 from Pro3→ Tyr3 to give the lacI-I12 mutation (Schmitz et al., 1978). This Lac repressor mutant was then fused to the GFP12 and GFP13 sequences exactly as described for pAFS78 to give pAFS135 and pAFS144, respectively. Plasmids pAFS135 and pAFS144 were linearized with NheI and transformed into yeast strain AFS34 for expression of GFP-LacI fusions in yeast. Lac operators were introduced at the centromere of chromosome III as previously described using pAFS59 (Straight et al., 1996). GFP-Tubulin was expressed by integration of pAFS91 as previously described (Straight et al., 1997).

Time-Lapse Microscopy and Image Analysis

Images were acquired as described (Straight et al., 1997) except that the actual length of spindles in kip3Δ cells was calculated by tracing fluorescence intensities in three-dimensional image stacks using the program 3D Model that had been customized for length measurement (Chen et al., 1996). The data for wild-type spindle elongation is previously published (Straight et al., 1997) and used only for comparison to the motor mutant data.

Results

Positioning, assembly and elongation of the yeast spindle during mitosis requires microtubule motor proteins. Anaphase has two components: anaphase A, the movement of the chromosomes towards the spindle poles and anaphase B, the separation of the spindle poles. In budding yeast, anaphase B has two phases, a rapid initial elongation of the spindle that is followed by a period of slower elongation (Kahana et al., 1995; Yeh et al., 1995; Straight et al., 1997). To study the contributions of individual motor proteins to anaphase, we performed time lapse video microscopy on yeast cells individually deleted in three kinesin motors, Cin8p, Kip1p, or Kip3p. We visualized the mitotic spindle using a GFP fusion to the major α-tubulin (TUB1) and the centromere using a GFP-Lac repressor fusion bound to a tandem array of Lac operators integrated near the centromere of chromosome III (Straight et al., 1997). We measured the separation between the ends of the spindle and between the sister centromeres as cells went from metaphase to anaphase. These distances allow us to quantify chromosome to pole movement during anaphase A and the increase in the separation between the poles during anaphase B.

Cin8 Is Required for the Rapid Phase of Mitotic Spindle Elongation

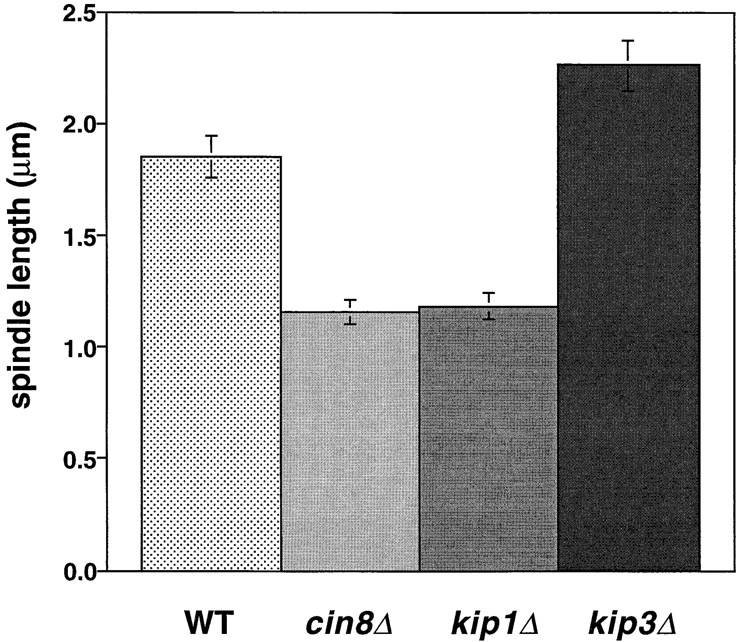

Fig. 1 shows records of mitosis in cin8Δ mutants. During metaphase, cin8Δ cells had shorter spindles (1–1.5 μm) than wild-type cells (1.5–2 μm; Figs. 1 A and 4). The suggestion that Cin8p is required for the full separation of the spindle pole bodies during metaphase is consistent with the role for Cin8p in spindle assembly described by Saunders and Hoyt (Saunders and Hoyt, 1992).

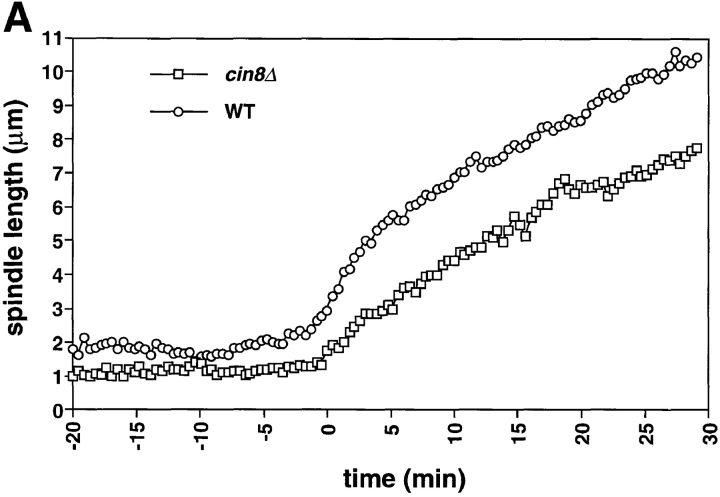

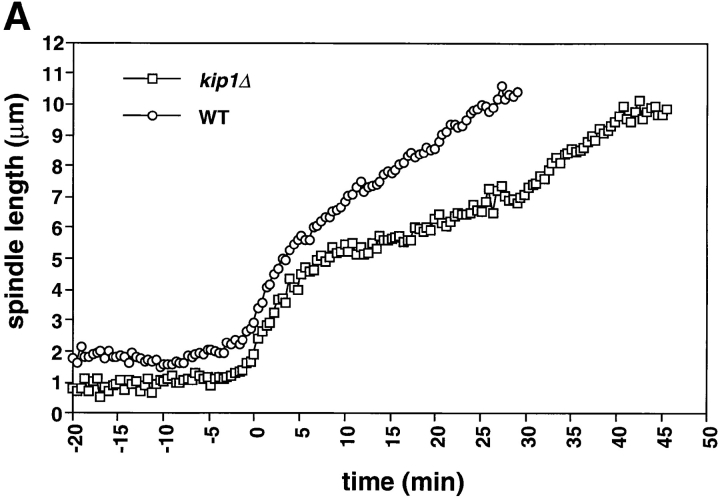

Figure 1.

cin8Δ cells are defective in the fast phase of anaphase B. A comparison of spindle elongation and centromere separation in wild-type and cin8Δ cells is shown. Cells of yeast strain AFS426 (cin8Δ) were arrested in G1 with α-factor then released from G1 and recorded as they progressed through mitosis. 12 optical sections at 0.5-μm intervals were acquired every 26 s. The distances between the spindle poles and the distances between the centromeres were measured in 3-dimensional space. (A) Distance between spindle pole bodies versus time. (B) Distance between centromeres versus time. The time of sister chromatid separation is indicated by t = 0.

Figure 4.

Motor mutations alter the length of the metaphase spindle. Metaphase spindle length in wild-type cells and motor mutants. The length of the bipolar spindle was measured in the 20–30-min interval before the initiation of anaphase in strains AFS403 (WT), AFS426 (cin8Δ), AFS404 (kip1Δ), and AFS417 (kip3Δ).

During anaphase, cin8Δ cells exhibited a defect in the rapid phase of spindle elongation. In wild-type cells the initial rapid separation of the spindle pole bodies (0.54 μm/min) was followed by a slower phase (0.21 μm/min; Table II; Straight et al., 1997). cin8Δ cells showed a uniformly slow spindle elongation whose rate (0.19 μm/min) was statistically indistinguishable from the slow phase of anaphase B in wild-type cells (Table II; Fig. 1 A). This defect suggests that Cin8p has a specific role in the initial rapid separation of the spindle poles but that other activities drive the slower phase of mitotic spindle elongation. The rapid initial separation of the centromeres in wild-type cells was not affected in the cin8Δ mutant (Fig. 1 B) suggesting that other factors are responsible for the initial separation. These could include the activity of other motors or the release of tension when the linkage between the sister chromatids dissolves.

Table II.

Spindle Dynamics in Wild-type and Kinesin Mutants

| Strain | Fast phase | Slow phase | Breakdown length | Anaphase duration | Anaphase A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm/min | μm/min | μm | min | |||||||

| WT | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 9.52 ± 0.49 | 26.6 ± 1.6 | 1.33 μm/min | |||||

| cin8Δ | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 6.95 ± 0.68 | 26.7 ± 2.4 | ND | |||||

| kip1Δ | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 9.79 ± 0.43 | 43.0 ± 3.1 | ND | |||||

| kip3Δ | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 12.31 ± 0.25 | 38.5 ± 3.1 | 1.30 μm/min |

Rates of spindle elongation were calculated using linear regression analysis in the same time intervals used to calculate the wild-type rates for the fast and slow phases of anaphase. Measurements shown in bold are significantly different from wild-type rates and all rates are displayed as the mean ± SE. The average breakdown length and the average duration of anaphase were calculated using the final timepoint before spindle disassembly. The total number of records analyzed for measurements of WT, cin8Δ, kip1Δ, and kip3Δ are n = 6, n = 5, n = 5, and n = 7, respectively.

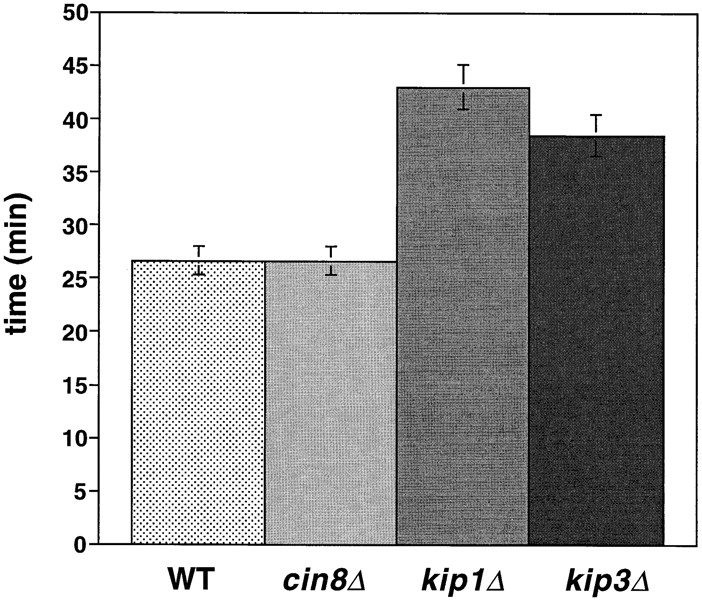

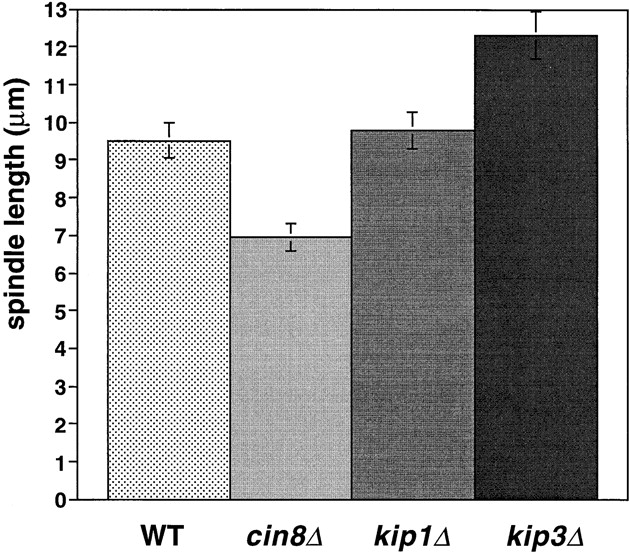

Although cin8Δ cells are defective for the rapid phase of anaphase B, the longer slow phase of anaphase B allows them to complete mitosis. cin8Δ spindles disassemble at the same time after anaphase initiation as do wild-type cells (Table II; Fig. 2) but with a shorter length (7.0 ± 0.7 μm) than that of wild-type cells (9.5 ± 0.5 μm). Much of this length difference can be accounted for by the slower elongation of cin8Δ spindles during the 5 min when wild-type cells are elongating their spindle rapidly ([0.55 μm/min {WT} − 0.2 μm/min {cin8Δ}] × 5 min = 1.8 μm).

Figure 2.

Motor mutants affect the duration of anaphase. Duration of anaphase in wild-type cells and motor mutants. The average time between the separation of sister chromatids and the breakdown of the spindle was calculated from video records of strains AFS403 (WT), AFS426 (cin8Δ), AFS404 (kip1Δ) and AFS417 (kip3Δ).

Kip1 Affects the Slow Phase of Mitotic Spindle Elongation

Cin8p and Kip1p have overlapping roles during spindle assembly and elongation (Roof et al., 1992; Saunders et al., 1997; Saunders and Hoyt, 1992). We examined kip1Δ cells during mitosis to determine whether differences exist between the two motors. Consistent with prior measurements in cells arrested in S phase (Saunders et al., 1997), and like cin8Δ cells (1.2 μm), kip1Δ cells (1.2 μm) had shorter metaphase spindles than wild-type cells (1.8 μm; see Fig. 4). This result supports the idea that Cin8p and Kip1p work together to maintain the mitotic spindle at its proper metaphase length (Saunders and Hoyt, 1992). The distances we have measured are slightly larger than the distances measured in hydroxyurea arrested cells for wild-type, cin8Δ and kip1Δ (Saunders et al., 1997). Our measurements of metaphase spindle length were made using video records of the 20–30 min preceding sister chromatid separation. The differences between hydroxyurea arrested and G2/M cells may reflect a difference between cells arrested by the DNA replication checkpoint and mitotic cells, a difference between cells with unreplicated centromeres and replicated centromeres, or differences between measurements made on live and fixed samples.

During anaphase, kip1Δ cells exhibited a normal rapid elongation phase (0.51 μm/min; Fig. 3 A; Table II) in contrast to cin8Δ cells, whose spindles elongate slowly. However, during the slow phase of spindle elongation in anaphase B, the spindles of kip1Δ cells (0.12 μm/min) elongated more slowly than wild-type spindles (0.2 μm/min; Fig. 3 A; Table II). This suggests that Kip1p and Cin8p have distinct roles in anaphase B: Cin8p is required for rapid elongation at the beginning of mitosis and Kip1p is more important during the slower phase of spindle elongation.

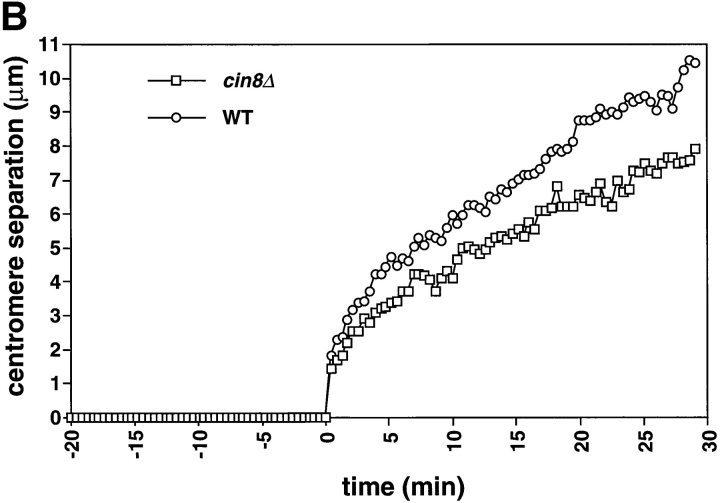

Figure 3.

kip1Δ cells are defective in the slow phase of anaphase B and prolong anaphase. kip1Δ cells (yeast strain AFS404) were recorded as described in Fig. 1. (A) Distance between spindle pole bodies versus time. (B) Distance between centromeres versus time. The time of sister chromatid separation is indicated by t = 0.

The period from the onset of anaphase to spindle breakdown was ∼15 min longer in kip1Δ cells than it was in wild-type or cin8Δ cells. The longer duration of anaphase compensated for the slower rate of spindle elongation with the result that kip1Δ cells elongated their spindles to the same final length as wild-type cells (9.5–10 μm; Figs. 3 A and 6; Table II). We could not tell whether the loss of Cin8p or Kip1p affected chromosome to pole movement (anaphase A) because the shorter metaphase spindle in cin8Δ and kip1Δ cells made it impossible to measure this movement.

Figure 6.

Motors regulate the final length of the anaphase spindle. Spindle breakdown length in wild-type and motor mutants. The final breakdown length of the anaphase spindle was calculated using the timepoint before spindle breakdown in strains AFS403 (WT), AFS426 (cin8Δ), AFS404 (kip1Δ), and AFS417 (kip3Δ).

Kip3 Affects Microtubule Length and Spindle Breakdown in Mitosis

Deletion of KIP3 increases the metaphase spindle length compared with wild-type cells. Metaphase spindles in kip3Δ cells were on average 0.4 μm longer than those in wild-type cells (Figs. 4 and 5 A). This increase is similar to that seen in the comparison between fixed kip3Δ and wild-type cells arrested in S phase (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997). Unlike Cin8p and Kip1p, Kip3p opposes extension of the metaphase spindle, either by exerting an inward directed force or by reducing the length of spindle microtubules. Because kip3Δ cells have longer astral microtubules and their spindles are resistant to depolymerization with the drug benomyl (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997), destabilization of the central spindle microtubules by Kip3p is the more likely mechanism for regulating spindle length.

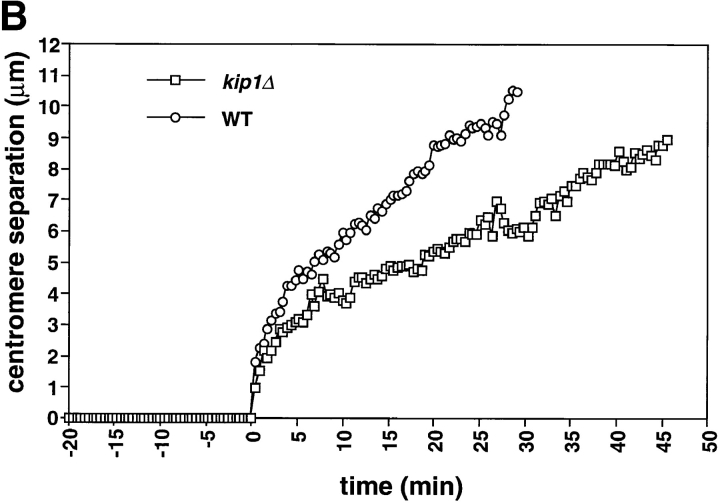

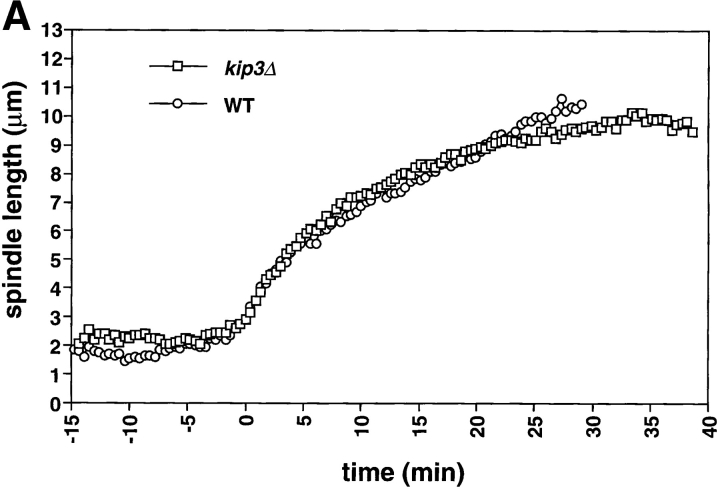

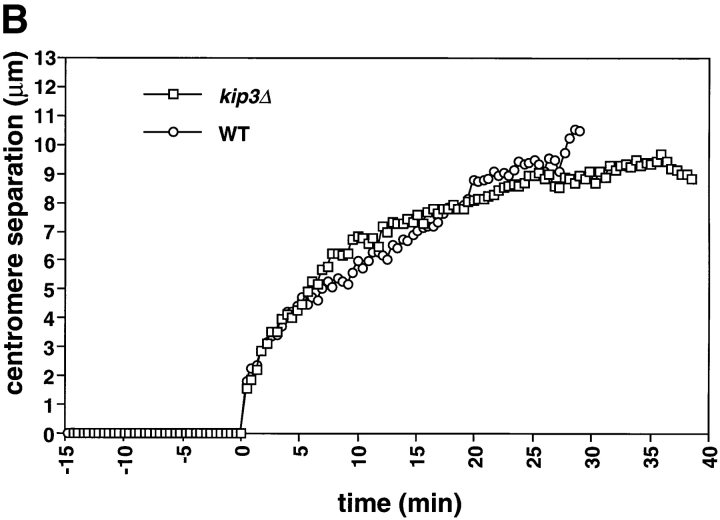

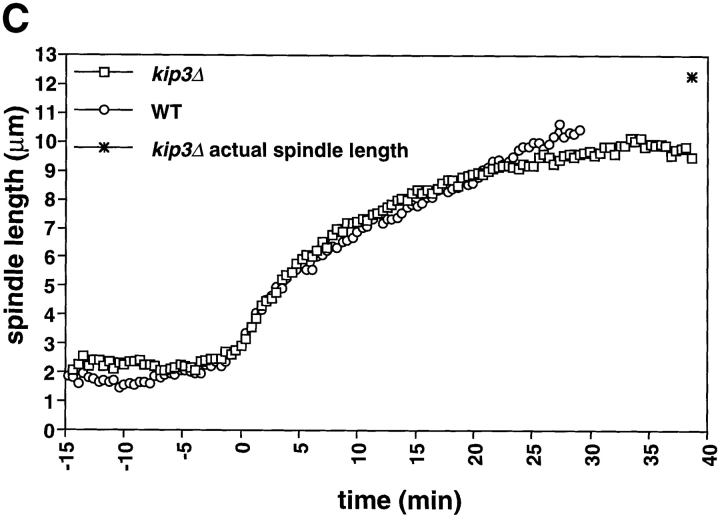

Figure 5.

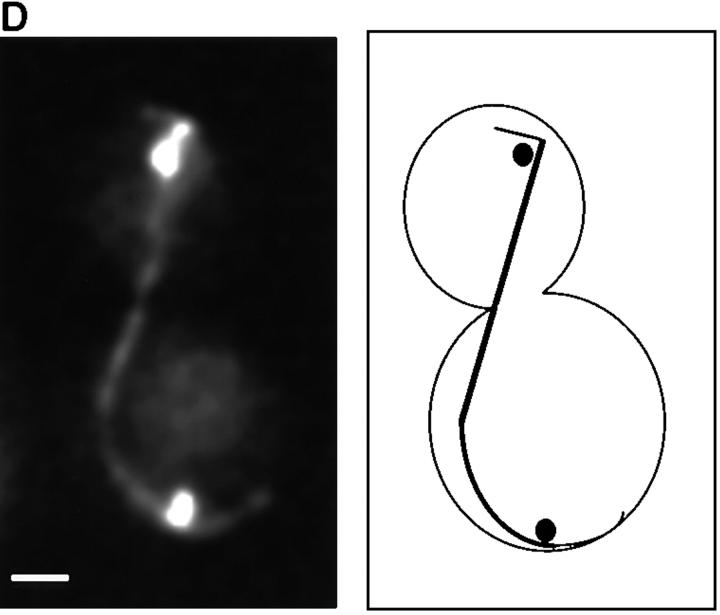

The length of the spindle and the duration of anaphase are regulated by Kip3. Cells deleted for Kip3 (AFS417) were recorded as described in Fig. 1. (A) Distance between spindle pole bodies versus time. (B) Centromere separation versus time. (C) Measurement of actual spindle length in three dimensions. Asterisk represents the total length of the spindle as compared with the distance between the spindle pole bodies. (D) Bent spindle at the end of anaphase in kip3Δ cell. Twelve 0.5-μm axial sections through a kip3Δ cell were projected onto two dimensions (left), a schematic of the cell is also shown (right). The bright dots of staining are the GFP-LacI staining of the centromeres. Bar, 2.0 μm.

Examining kip3Δ cells during anaphase revealed a specific role for Kip3 in regulating spindle breakdown. Initial anaphase spindle elongation occurred normally in kip3Δ cells, consistent with measurements of spindle pole separation in fixed samples (DeZwaan et al., 1997). The rates of the rapid (0.56 μm/min) and slow phases (0.17 μm/min) of spindle elongation in kip3Δ cells were statistically indistinguishable from those of wild-type cells (Fig. 5 A; Table II). Although the rates of spindle elongation in wild-type and kip3Δ are similar, kip3Δ cells broke down their spindles 12 min later than wild-type cells (Fig. 2; Table II). This observation contrasts with earlier measurements on populations of fixed kip3Δ cells, that showed that the distance between fluorescently labeled spindle pole bodies stopped increasing at the same time in wild-type and kip3Δ cells (DeZwaan et al., 1997). However, in all but one of our sequences (n = 7), spindles persisted in kip3Δ cells after the time at which the spindle in wild-type cells broke down. This difference is probably explained because previous work assumed that spindle breakdown occurred at the time when the distance between the spindle poles stopped increasing.

Cells lacking Kip3p elongate their spindles beyond the length of wild-type cells. Although the pole to pole distance in kip3Δ stops increasing at ∼10 μm (Fig. 5 A), the spindles keep elongating, making them bend before they break down (Fig. 5 D). To confirm this interpretation, we measured the length of the bent kip3Δ spindles in three- dimensional space. Although the spindle pole bodies were only separated by 10 μm, the actual spindle length increased to more than 12 μm (Figs. 5 C and 6; Table II). Kip3p may therefore be involved in destabilizing microtubules at the end of mitosis so that the spindle can disassemble at the proper time and at the proper length. Bowed spindles have also been observed in wild-type fission yeast, although in this organism the spindle poles do not have to reach the ends of the cell for bending to occur (Hagan and Hyams, 1996).

Motor Mutants Delay the Onset of Anaphase

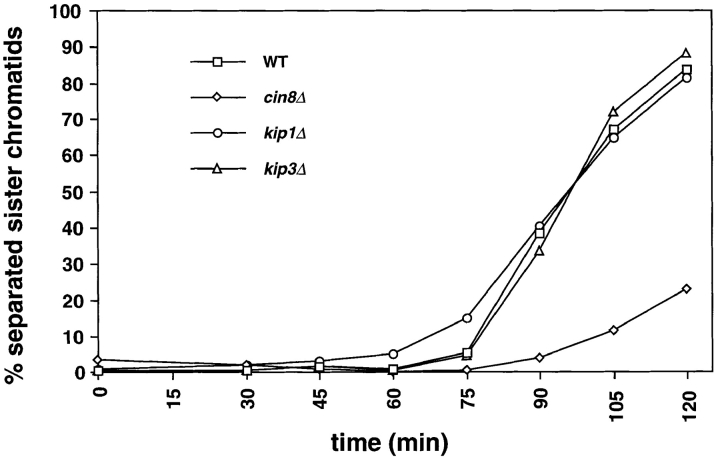

We investigated the effect of motor mutations on the interval between spindle assembly and the onset of anaphase. Wild-type, cin8Δ, kip1Δ, and kip3Δ mutants that contained GFP-marked tubulin and CENIII were arrested in G1 by treatment with the yeast mating pheromone α-factor. The cells were released from this arrest and population samples were removed at intervals and scored for spindle elongation and sister chromatid separation. Cells deleted for Kip1p or Kip3p initiated anaphase at the same time as wild-type cells and progressed through anaphase with similar kinetics (Fig. 7). Cells lacking Cin8p showed a dramatic delay in the initiation of anaphase. 90 min after release from α-factor, >30% of wild-type, kip1Δ, and kip3Δ cells had initiated anaphase compared with only 4% of cin8Δ cells. When >80% of wild-type, kip1Δ and kip3Δ cells had initiated anaphase (t = 120), <25% of cin8Δ cells had separated their sister chromatids (Fig. 7). We have also observed delays in the onset of anaphase in cells lacking Kar3p (data not shown). The prolonged metaphase of motor mutants is probably due to the action of the spindle checkpoint (reviewed in Nicklas, 1997; Rudner and Murray, 1996), which delays anaphase until all chromosomes are correctly aligned on a bipolar spindle. Inactivation of the checkpoint allows cells with spindle defects to exit from mitosis and kills kar3Δ and cin8Δ mutants, which have the most profound delays in mitosis (Roof et al., 1991; Geiser et al., 1997).

Figure 7.

Motor mutants delay anaphase onset. cin8Δ causes a delay in the entry into anaphase. Strains AFS501 (WT), AFS426 (cin8Δ), AFS404 (kip1Δ), and AFS417 (kip3Δ) were synchronized in G1 by treatment with 10 μg/ml α-factor. Cells were released from the block and were assayed for sister chromatid separation at 15 minute intervals as previously described (Straight et al., 1996). The percentage of cells with separated sister chromatids versus time is shown.

Discussion

We performed video microscopy on microtubule motor mutants whose microtubules and a centromere had been marked with GFP. Our analysis reveals that each motor mutant has distinct defects in anaphase spindle elongation.

Separate Roles for Motors during Anaphase

Our results show that Cin8p and Kip1p have distinct roles during anaphase. Previous studies on fixed cells showed that Cin8p and Kip1p have partially redundant roles in pushing the spindle poles apart (Hoyt et al., 1992, 1993; Roof et al., 1992; Saunders and Hoyt, 1992; Saunders et al., 1997) and analysis of living cells showed that Cin8p, Kip1p, and dynein cooperate to give robust DNA separation during mitosis (Saunders et al., 1995). These observations did not reveal that Cin8p and Kip1p are important for different phases of anaphase. We have shown that Cin8p functions early in the separation of the spindle pole bodies and is required for the rapid phase of anaphase spindle elongation. Unlike Cin8p, Kip1p plays no role in controlling the rapid phase of spindle elongation. Cells deleted for Kip1p perform the initial phase of anaphase normally but are then compromised in the slower phase of spindle elongation.

The difference between the rates of the two phases of anaphase B in wild-type cells could be explained in many ways. One explanation is that the rate of the rapid phase is set by the rate at which motors slide the microtubules from opposite poles of the spindle past each other and that the rate of the slow phase is set by the rate of the microtubule growth required to maintain an overlap zone as the spindle extends. In the rapid phase, Cin8p would move microtubules past each other more rapidly than Kip1p. During the slow phase, the deletion of KIP1 would affect the rate of microtubule growth, but the deletion of CIN8, would not. Cut7p, a fission yeast homologue of Cin8p and Kip1p, localizes to the midzone of the spindle during anaphase B (Hagan and Yanagida, 1992). Experiments in isolated diatom spindles suggest that the rate of spindle elongation is strongly influenced by factors that control the speed at which microtubules grow (Masuda and Cande, 1987). Another possibility is that both rates of anaphase B are set by the speed of microtubule sliding and that Cin8p is a faster motor that is only active during early anaphase B, whereas Kip1p is a slower motor active throughout anaphase B.

Cells lacking Kip3p delay spindle breakdown and their final spindles are so long that they become physically deformed when they run into the ends of the cell. Previous studies suggested that Kip3p may regulate the stability of microtubules (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997). In our experiments, metaphase kip3Δ spindles were longer than those of wild-type cells in agreement with spindle length measurements in hydroxyurea arrested cells (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997). Once anaphase began, kip3Δ cells behaved exactly like wild-type cells until the time of spindle breakdown: when wild-type spindles broke down, kip3Δ spindles remained intact and continued to elongate. The ability of the spindle to elongate beyond the cell length has implications for the mechanism of spindle elongation. The buckling of the spindle in kip3Δ indicates that some or all of the force elongating the spindle must be generated within the spindle, pushing the poles apart. If spindle elongation was driven by a pulling force generated by interactions of astral microtubules with the cortex at the ends of the cell, the length of the spindle could not exceed that of the cell. In the phytopathogenic fungus Nectria haematococca and in rat kangaroo kidney epithelial cells (PtK2 cells), severing the central spindle during anaphase increased the rate of spindle pole separation suggesting that interactions in the central spindle were limiting the rate of spindle elongation and that astral pulling forces can drive spindle elongation (Aist et al., 1991, 1993). We do not know if the apparent discrepancy between these observations and our own is due to different factors regulating the extent versus the speed of anaphase B, or differences between the mechanism of spindle elongation in different organisms.

Regulation of Spindle Breakdown

In most organisms, the position of the metaphase spindle dictates the plane of cell division (Rappaport, 1996), ensuring that each daughter cell receives one set of chromosomes. In budding yeast, cell division occurs at the neck that separates mother and bud and this site is defined before spindle formation. As a result, cells must ensure that the anaphase spindle passes through the neck so that the mother receives one set of chromosomes and the bud the other. Studies of dynein mutants reveal a mechanism to achieve this: the anaphase spindle does not break down until one of its poles and the associated set of chromosomes has entered the bud (Yeh et al., 1995).

Our analysis of kinesin mutants suggests that the regulation of spindle breakdown is complex. Compared with wild-type cells, the spindles of cin8Δ break down at the same time after the onset of anaphase and at shorter final lengths, those of kip1Δ break down later but at the same final length and those of kip3Δ cells break down later and at a greater final length.

One explanation of these differences is that compression of the spindle as it contacts the ends of the cell at the end of anaphase promotes spindle disassembly by promoting the action of microtubule-destabilizing factors. This idea is supported by the observation that microtubules assembled from pure tubulin can be extensively bent in vitro without causing them to break. In contrast, bent microtubules of lower radius of curvature are observed to break more frequently than straight microtubules in the cytoplasm of vertebrate cells. This higher susceptibility of bent microtubules to breakage in the cytoplasm is thought to reflect enhanced action of microtubule-destabilizing factors at sites weakened by bending (Odde, D., personal communication). The increased length of astral microtubules in kip3Δ cells and the resistance of kip3Δ cells to benomyl suggest that Kip3p acts directly or indirectly as a microtubule-destabilizing factor. Thus, the spindle in kip3Δ cells would be more resistant to compression-triggered disassembly at the end of anaphase and the spindle would bend as observed. In kip1Δ cells, spindle breakdown would still be triggered by the collision of the spindle poles with the ends of the cell, but, because spindle elongation is slower, spindle breakdown would occur later than in wild-type cells. In cin8Δ cells, the spindle may exhibit increased susceptibility to compression. Thus, the weaker compressive forces resulting from the deformation of the nuclear envelope as the spindle elongates would be sufficient to trigger spindle breakdown.

An alternative hypothesis to explain our results is that the timing of spindle breakdown in the different motor mutants is influenced by both the state of the cell cycle machinery and the effects of microtubule motors on microtubule dynamics. In this hypothesis, changes in the cell cycle machinery would destabilize nuclear microtubules leading to spindle breakdown. Possible changes include the inactivation of Cdc28 and the APC-mediated destruction of Ase1p. Ase1p has been shown to regulate spindle breakdown: Ase1p localizes to the spindle midzone, ase1Δ mutants have unstable spindles in late anaphase, and indestructible Ase1p results in a delay in spindle breakdown producing a phenotype similar to kip3Δ (Pellman et al., 1995; Juang et al., 1997). In cin8Δ mutants, the cell cycle– induced destabilization would occur normally so that spindles break down at the same time as they do in wild-type. In contrast, Kip1p and Kip3p may be required to induce the microtubule depolymerization that destroys the spindle. In the absence of either of these kinesins, although the change in the cell cycle machinery would occur normally, it would take longer for this change to induce spindle breakdown. The difference in the final lengths of the kip1Δ and kip3Δ spindles would simply reflect the different rates of spindle elongation in these mutants.

It is likely that the fidelity of anaphase results from the regulation of multiple independent properties including cell cycle timing of spindle elongation, absolute spindle length, spindle microtubule dynamics, and motor protein activity. Determining how these properties are built into the chemistry of motor proteins and how they are regulated by the cell should be informative in understanding the regulation of anaphase.

Genetic Redundancy and Functional Overlap

The distinct phenotypes of cin8Δ and kip1Δ cells have implications for the concepts of genetic redundancy and functional overlap between related genes. Groups of two or more genes are said to be redundant if deletion of a single member of the family produces little or no phenotype, but deletion of all members of the group is lethal. KIP1 and CIN8 are partially redundant since kip1Δ mutants have very mild phenotypes and mild overexpression of Kip1p suppresses the phenotype of cin8Δ (Hoyt et al., 1992; Roof et al., 1992). One interpretation of these observations is that the two motors perform essentially identical functions and differ only in their level of expression. If this were so, the phenotypes of kip1Δ and cin8Δ might differ quantitatively but not qualitatively. Our observation that two mutants have distinct effects on different aspects of anaphase argues that the motors have distinct functions, but that these functions have overlapping roles in producing spindle elongation. We believe that careful study of genes that appear to be redundant will reveal that in most cases their functions are qualitatively as well as quantitatively different.

The phenotypes of motor mutants highlight the distinction between minimal and full systems for performing complex cellular tasks like chromosome segregation. A minimal system suffices to perform a task at a level that allows cells to reproduce indefinitely under optimal conditions. Cells with two functional motors can function at this level (Hoyt, A., personal communication). A full system performs a task with high fidelity in the face of environmental, physiological, and genetic perturbations. For mitosis one criterion of the full system is a very low rate of errors in chromosome segregation. Lack of Cin8p disrupts the full system, since cin8 mutants were first found because they lead to errors in chromosome segregation (Hoyt et al., 1990). A more general criterion for including a function in the full system is that it makes cells more susceptible to genetic perturbations. Mutations in any one of the mitotic motors (Cin8p, Kip1p, Kip3p, Kar3p, and dynein) make at least one of the remaining mitoic motors essential for cell proliferation (Hoyt et al., 1992; Roof et al., 1992; Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). Different organisms may use different additional functions to convert a minimal system into a full one. Thus fission yeast appear to possess a single motor, Cut7, of the BimC class, whereas budding yeast possess two, Cin8 and Kip1. This difference may reflect the historical accidents of evolution, or the more critical role of spindle elongation in budding yeast, where one of the daughter nuclei must be transported through the bud neck to produce two viable and genetically identical progeny. Detailed analysis of the requirements for mitosis in budding yeast and other organisms should illuminate how minimal systems for chromosome segregation arose and were then evolved into the highly efficient and regulated machines found today.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Odde and Andy Hoyt for communicating their unpublished results; members of the Murray laboratory, A. Desai, T.J. Mitchison, and J.M. Scholey for critical review of the manuscript; and Diana Diggs for customization of image processing software during data analysis.

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health and the Packard Foundation.

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Dr. Aaron F. Straight at his present address Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, 240 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115. Tel.: (617) 432-3728. Fax: (617) 432-3702. E-mail: aaron_straight@hms.harvard.edu

References

- Aist JR, Bayles CJ, Tao W, Berns MW. Direct experimental evidence for the existence, structural basis and function of astral forces during anaphase B in vivo. J Cell Sci. 1991;100:279–288. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aist JR, Liang H, Berns MW. Astral and spindle forces in PtK2 cells during anaphase B: a laser microbeam study. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:1207–1216. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carminati JL, Stearns T. Microtubules orient the mitotic spindle in yeast through dynein-dependent interactions with the cell cortex. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Hughes DD, Chan TA, Sedat JW, Agard DA. IVE (image visualization environment): a software platform for all three-dimensional microscopy applications. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:56–60. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham FR, Hoyt MA. Mitotic spindle positioning in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis accomplished by antagonistically acting microtubule motor proteins. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1041–1053. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross FR. ‘Marker swap' plasmids: convenient tools for budding yeast molecular genetics. Yeast. 1997;13:647–653. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970615)13:7<647::AID-YEA115>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeZwaan TM, Ellingson E, Pellman D, Roof DM. Kinesin-related KIP3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis required for a distinct step in nuclear migration. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1023–1040. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endow SA, Kang SJ, Satterwhite LL, Rose MD, Skeen VP, Salmon ED. Yeast Kar3 is a minus-end microtubule motor protein that destabilizes microtubules preferentially at the minus ends. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1994;13:2708–2713. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshel D, Urrestarazu LA, Vissers S, Jauniaux JC, van Vliet-Reedijk JC, Planta RJ, Gibbons IR. Cytoplasmic dynein is required for normal nuclear segregation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11172–11176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser JR, Schott EJ, Kingsbury TJ, Cole NB, Totis LJ, Bhattacharyya G, He L, Hoyt MA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes required in the absence of the CIN8-encoded spindle motor act in functionally diverse mitotic pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1035–1050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, et al. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274:563–567. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan I, Yanagida M. Kinesin-related cut7 protein associates with mitotic and meiotic spindles in fission yeast. Nature. 1992;356:74–76. doi: 10.1038/356074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan IM, Hyams JS. Forces acting on the fission yeast anaphase spindle. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;34:69–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)34:1<69::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald R, Tournebize R, Habermann A, Karsenti E, Hyman A. Spindle assembly in Xenopusegg extracts: respective roles of centrosomes and microtubule self-organization. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:615–628. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim R, Tsien RY. Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr Biol. 1996;6:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MA, Stearns T, Botstein D. Chromosome instability mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that are defective in microtubule-mediated processes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:223–234. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MA, He L, Loo KK, Saunders WS. Two Saccharomyces cerevisiaekinesin-related gene products required for mitotic spindle assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:109–120. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt MA, He L, Totis L, Saunders WS. Loss of function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinesin-related CIN8 and KIP1 is suppressed by KAR3 motor domain mutations. Genetics. 1993;135:35–44. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyett A, Kahana J, Silver P, Zeng X, Saunders WS. The Kar3p and Kip2p motors function antagonistically at the spindle poles to influence cytoplasmic microtubule numbers. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:295–301. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Salmon ED. Force generation by microtubule assembly/ disassembly in mitosis and related movements. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1619–1640. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang YL, Huang J, Peters JM, McLaughlin ME, Tai CY, Pellman D. APC-mediated proteolysis of Ase1 and the morphogenesis of the mitotic spindle. Science. 1997;275:1311–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana JA, Schnapp BJ, Silver PA. Kinetics of spindle pole body separation in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9707–9711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashina AS, Rogers GC, Scholey JM. The bimC family of kinesins: essential bipolar mitotic motors driving centrosome separation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1357:257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Yeh E, Hays T, Bloom K. Disruption of mitotic spindle orientation in a yeast dynein mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10096–10100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Suppression of a myosin defect by a kinesin-related gene. Nature. 1992;356:358–361. doi: 10.1038/356358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Immunofluorescence localization of the unconventional myosin, Myo2p, and the putative kinesin-related protein, Smy1p, to the same regions of polarized growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:825–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombillo VA, Nislow C, Yen TJ, Gelfand VI, McIntosh JR. Antibodies to the kinesin motor domain and CENP-E inhibit microtubule depolymerization-dependent motion of chromosomes in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:107–115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H, Cande WZ. The role of tubulin polymerization during spindle elongation in vitro. Cell. 1987;49:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, J.R., and C.M. Pfarr. 1991. Mitotic Motors. 115:577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meluh PB, Rose MD. KAR3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell. 1990;60:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90351-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.H., and W.S. Reznikoff. 1980. The Operon. In Cold Spring Harbor Monograph Series. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 469.

- Nicklas RB. How cells get the right chromosomes. Science. 1997;275:632–637. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellman D, Bagget M, Tu YH, Fink GR, Tu H. Two microtubule-associated proteins required for anaphase spindle movement in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1373–1385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, R. 1996. Cytokinesis in animal cells. In Developmental and cell biology series 32. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. 386.

- Rodionov VI, Gyoeva FK, Tanaka E, Bershadsky AD, Vasiliev JM, Gelfand VI. Microtubule-dependent control of cell shape and pseudopodial activity is inhibited by the antibody to kinesin motor domain. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1811–1820. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof DM, Meluh PB, Rose MD. Multiple kinesin-related proteins in yeast mitosis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:693–703. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof DM, Meluh PB, Rose MD. Kinesin-related proteins required for assembly of the mitotic spindle. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:95–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner AD, Murray AW. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:773–780. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E.F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Saunders WS, Hoyt MA. Kinesin-related proteins required for structural integrity of the mitotic spindle. Cell. 1992;70:451–458. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90169-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders WS, Koshland D, Eshel D, Gibbons IR, Hoyt MA. Saccharomyces cerevisiaekinesin- and dynein-related proteins required for anaphase chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:617–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders W, Lengyel V, Hoyt MA. Mitotic spindle function in Saccharomyces cerevisiaerequires a balance between different types of kinesin-related motors. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1025–1033. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.6.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Coulondre C, Miller JH. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. V. Repressors which bind operator more tightly generated by suppression and reversion of nonsense mutations. J Mol Biol. 1978;123:431–454. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SL, Yeh E, Maddox P, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Astral microtubule dynamics in yeast: a microtubule-based searching mechanism for spindle orientation and nuclear migration into the bud. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:985–994. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., G. Fink, and C. Lawrence. 1974. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Siemering KR, Golbik R, Sever R, Haseloff J. Mutations that suppress the thermosensitivity of green fluorescent protein. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1653–1663. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70789-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer WP. Rapid evolution of a protein in vitro by DNA shuffling. Nature. 1994;370:389–391. doi: 10.1038/370389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Belmont AS, Robinett CC, Murray AW. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Marshall WF, Sedat JW, Murray AW. Mitosis in living budding yeast: anaphase A but no metaphase plate. Science. 1997;277:574–578. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisberg EA, Koonce MP, McIntosh JR. Cytoplasmic dynein plays a role in mammalian mitotic spindle formation. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:849–858. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernos I, Karsenti E. Motors involved in spindle assembly and chromosome segregation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:4–9. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak CE, Mitchison TJ, Desai A. XKCM1: a Xenopuskinesin-related protein that regulates microtubule dynamics during mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 1996;84:37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E, Skibbens RV, Cheng JW, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Spindle dynamics and cell cycle regulation of dynein in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . J Cell Biol. 1995;130:687–700. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]