Abstract

A phylogeny and timescale derived from analyses of multilocus nuclear DNA sequences for Holarctic genera of plethodontid salamanders reveal them to be an old radiation whose common ancestor diverged from sister taxa in the late Jurassic and underwent rapid diversification during the late Cretaceous. A North American origin of plethodontids was followed by a continental-wide diversification, not necessarily centered only in the Appalachian region. The colonization of Eurasia by plethodontids most likely occurred once, by dispersal during the late Cretaceous. Subsequent diversification in Asia led to the origin of Hydromantes and Karsenia, with the former then dispersing both to Europe and back to North America. Salamanders underwent rapid episodes of diversification and dispersal that coincided with major global warming events during the late Cretaceous and again during the Paleocene–Eocene thermal optimum. The major clades of plethodontids were established during these episodes, contemporaneously with similar phenomena in angiosperms, arthropods, birds, and mammals. Periods of global warming may have promoted diversification and both inter- and transcontinental dispersal in northern hemisphere salamanders by making available terrain that shortened dispersal routes and offered new opportunities for adaptive and vicariant evolution.

Keywords: historical biogeography, paleogeography, Plethodontidae dispersal, salamander phylogeny, phylogeny

Plethodontidae, the most speciose family of salamanders, is also the most differentiated in morphology, ecology, and behavior. The family includes ≈68% of the extant described species of caudate amphibians (1). New analyses of mtDNA, nuclear DNA, and morphology (2–6) have achieved consensus on many aspects of phylogenetic relationships, but unresolved conflicts remain. The disjunct and highly asymmetric Holarctic distribution of the family, with ≈98% of the species in the Americas and a few in the Mediterranean region, has long been a biogeographic puzzle (7–9), with the debate centered on the timing and route of colonization of Eurasia (reinvigorated with the recent discovery of Karsenia, the first East Asian plethodontid; ref. 10). The distribution of the supergenus (Sg) Hydromantes, with representatives in western North America and in the Mediterranean, has been considered enigmatic, even paradoxical, given the high degree of philopatry, small ranges, and low dispersal capacity of plethodontids (11). Two hypotheses have been proposed: a dispersal event from eastern North America to Europe across the Paleocene–Eocene North Atlantic land bridge (NALB) (12, 13), or via later Cenozoic movement across the Bering land bridge, from western North America to Europe (8). Plethodontidae are thought to have originated in the Appalachian region, because of ideas of the origin of lunglessness (universal in the family), the presence of many early branched lineages in the region, and the great age of the mountain system (14, 15), but these ideas have been questioned (2, 16). New phylogenetic analyses identify long-established lineages in western North America, and some clades are spread across the continent. Here we test hypotheses on the origin, dispersal, and pattern of diversification of the main lineages in the family by generating a large nuclear sequence dataset (≈2.7 kb per species from 3 single-copy protein-coding nuclear genes for 43 salamander taxa, and several outgroups), which we analyze to produce a robust phylogenetic hypothesis, as well as hypotheses on the origin and times of divergence of the main lineages. Our focus is the evolutionary history, phylogenetic relationships, and historic biogeography of Holarctic plethodontids. Although some bolitoglossines, which account for 60% of plethodontids, are included here, this deeply nested clade centered in the American tropics is treated elsewhere (17).

Results and Discussion

Phylogenetic Relationships Among Plethodontids.

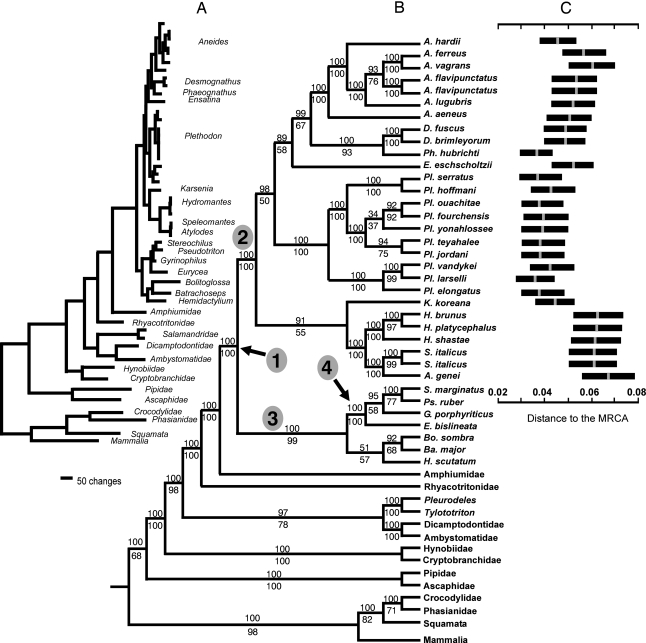

Our results require taxonomic changes, explained in supporting information (SI) Text. Two major clades are recovered with strong statistical support (Fig. 1); the Plethodontinae (including Plethodon, Karsenia, Sg Hydromantes, Ensatina, Sg Desmognathus, and Aneides) and the Hemidactyliinae. Two subclades of Hemidactyliinae are recovered, one of which (Spelerpini: Eurycea, Gyrinophilus, Pseudotriton, Stereochilus) is well supported, and the other (including Hemidactylium, Batrachoseps, and Sg Bolitoglossa) with less statistical support. Shimodaira-Hasegawa nonparametric likelihood ratio test (SHT) results, congruent with the maximum likelihood (ML) support values, were unable to reject different placements on the tree (SI Table 1), but the strong Bayesian support for the exclusively North American lineages (Plethodon and relatives) leaves Karsenia and Sg Hydromantes, recovered as sister taxa, outside that clade. Sg Hydromantes is monophyletic, with two major clades corresponding to European and North American species. A monophyletic Plethodon is sister to a clade of the remaining taxa, for which support is not strong. Ensatina is sister to Sg Desmognathus (itself a well supported clade) + Aneides. Aneides is monophyletic, with the eastern species (A. aeneus) sister to a clade constituted of the central (A. hardii) + western species. Plethodon contains two well supported subclades corresponding to the eastern and western species. Eastern small and eastern large species of Plethodon also constitute two reciprocally monophyletic clades. Data are significantly less supportive of paraphyly of Plethodon, with Aneides nested within it (SHT; SI Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of Holarctic plethodontids. (A) ML phylogram. (B) The 50% majority consensus rule cladogram of trees resulting from Bayesian analyses. Upper values on nodes represent Bayesian posterior probability, and lower ones represent ML bootstrap proportion. (C) Bayesian relative rate tests showing the relative branch length for every species using spelerpines as most recent common ancestor; note that most rapid rates of evolution occurred in Sg Hydromantes. In the cladogram, numbers encircled in gray refer to family Plethodontidae (1), subfamilies Plethodontinae (2) and Hemidactylinae (3), and tribe Spelerpini (4), respectively.

Timescale for Plethodontid Origin and Diversification.

Major issues in dating cladogenetic events by using fossil and biogeographic data and molecularly based phylogenetic hypotheses are the frequent differences in evolutionary rates among genes and taxa (18) as well as the accuracy of the age constraints available (19). We used a partitioning scheme and relaxed molecular clock method (20). We investigated the effects of constraining some nodes with well supported dating based on paleontological criteria (21). Preliminary tests suggested that these parameters often have strong effects on time estimates, especially on 95% confidence intervals (SI Text). Multiple age constraints give more accurate estimates for young nodes, but inclusion of ancient, well constrained nodes (21) is critical to estimate old splits. Although this suggests that but a few such calibrations would be sufficient to estimate ancient splits, younger constraints are necessary to adequately estimate divergences for recent splits.

Our analyses (Fig. 2 and SI Table 2) agree with other studies in dating the split between frogs and salamanders in the Carboniferous (19, 22–25). This age and that recently estimated for the split between amphibians and amniotes (late Devonian; ref. 26) seem too old according to the fossil record (27). A Mesozoic origin for salamanders has been proposed based on the fossil record (28, 29), and by most of the molecular studies available so far (19, 24, 25), although a late Paleozoic diversification of salamanders has also been suggested (23). Our data are in agreement with other studies (19, 25) that date the initial split within modern salamanders almost immediately after the Permo-Triassic mass extinction. A younger origin, in the Jurassic, has been proposed (24); although that study used methods similar to ours, only a single fossil age constraint was used, as well as a combination of parameter values (old bigtime value, rttmsd constrained to 10 million years) that we show (SI Text) consistently underestimate divergence times.

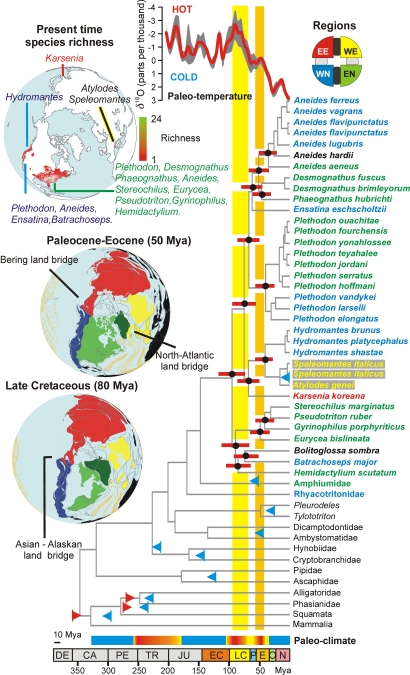

Fig. 2.

Chronogram for the taxa analyzed. Data were calculated with MULTIDIVTIME using a prior of 20 mya for rttmsd, a bigtime of 420 mya, and lower fossil constraints. Branch lengths are proportional to time units. Red bars represent 95% confidence intervals; blue and red triangles represent minimum and maximum fossil time constraints, respectively. At the top right, a color-coded wheel represents the four main regions considered: EE (red), eastern Eurasia; WE (yellow), western Eurasia; EN (green), eastern North America; WN (blue), western North America. The same color-coding scheme was applied to species names and paleogeographic reconstructions for the Paleocene–Eocene and Late Cretaceous (shown at left). Tectonic plates and ocean isochrones are overlapped in gray and orange, respectively (29). Actual species richness for the Holarctic plethodontid genera is represented at top left. All geographic reconstructions are orthographically projected, with −60° set as the central meridian and 85° set as the reference latitude. At the top of the chronogram is a chart representing the evolution of the deep-sea oxygen δ18 isotope across time, with the smoothed mean highlighted in red and the 75% interval in gray. Paleoclimate is indicated by a bar at the bottom coded from blue to red, representing glaciations and cold-to-hot periods, respectively. Time scale is shown at the bottom, with letters representing geologic periods (DE, Devonian; CA, Carboniferous; PE, Permian; TR, Triassic; JU, Jurassic; EC, Early Cretaceous; LC, Late Cretaceous; P, Paleocene; E, Eocene; O, Oligocene; N, Neogene).

The warm temperate climate in proto-Laurasia during the early Jurassic (Fig. 2; ref. 30) favored the diversification of many salamander lineages, which, according to our estimates, diverged in a relatively short period, predating the split of Pangea. Amphiumids and the ancestor of plethodontids diverged in the mid-Jurassic, but the initial split within plethodontids did not occur until the Late Cretaceous, just after the early Cretaceous glaciation (Fig. 2). Paleoclimatic reconstructions (Fig. 2) show two global warming periods: late Cretaceous and at the Paleocene–Eocene boundary. These periods coincide with episodes of rapid lineage diversification of plethodontids, as evidenced by the short internodes shown in the ML phylogram (Fig. 1). Low extinction rates might account for short internodes, but we would not expect to see the pattern of clustering at particular time intervals that we find.

Historical Biogeography of Plethodontids.

Plethodontids long were thought to have originated from stream-dwelling forms living in Appalachia that had lost lungs as a rheotropic adaptation (31). Appalachia was indicated by the high number of extant species and adaptive diversity in an old and stable mountain system (Fig. 2). A large molecular dataset was interpreted as either challenging (2) or supporting (3) this idea. The origin of lunglessness also has been debated (16, 31–34), and an analysis in the context of geologic history favored an Appalachian origin but did not reject a western North American or eastern Asian origin (16). We combined a robust phylogenetic hypothesis for all Holarctic genera, divergence time estimates, paleographic reconstructions, and a biodiversity analysis to examine the “Out of Appalachia” hypothesis. We propose an alternative scenario that agrees with all data available.

The major clades, Plethodontinae and Hemidactyliinae, both have representatives in eastern and western North America. The split between them is dated in the mid-Cretaceous ≈94 mya (SI Table 2). During the early Cretaceous, eastern and western North America were physically connected, but from ≈110 to 70 mya, increasing sea levels generated a marine midcontinental seaway separating these regions (Fig. 2; ref. 35). The Appalachian Mountains originated in the late Precambrian. By the end of the Mesozoic, they were mostly eroded, uplifting again during the Cenozoic. By the time the two main clades split, other mountain systems existed on the continent. A major vicariant event associated with the epicontinental seaway is the most parsimonious scenario for the early diversification of plethodontids, but our divergence time estimates suggest more recent transcontinental movements for Aneides and Plethodon (Fig. 2 and SI Table 2). Plethodon and Aneides occur in both eastern and western North America, with a large midcontinental gap and isolated species in New Mexico. Other taxa with low dispersal capacities (e.g., spiders; ref. 36) display a similar pattern. During the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) and Eocene thermal optimum (Fig. 2), diversification was higher, with splits of Aneides from the ancestor of Desmognathus and Phaeognathus, Eurycea from Gyrinophilus, Desmognathus from Phaeognathus, and Hydromantes from Speleomantes and Atylodes. Current diversity estimates (Fig. 2 Top) can be misleading if the ages of the clades are not considered. Plethodon and Desmognathus are the most speciose genera among the Plethodontinae, with centers of diversity in the Appalachian Mountains. However, these are relatively recent and rapid radiations, with high lineage accumulation in recent geologic times (6, 37), probably favored by the uplift of Appalachia in the Cenozoic and the reacquisition of aquatic larvae by desmognathines (2). The high species diversity in Appalachia corresponds mainly to recent radiations, but the ancestor of the family could have been distributed anywhere in North America. This hypothesis is supported by ancestral range reconstructions using Lagrange(ref. 38; SI Text). The biogeographic scenario with highest likelihood (L) suggests a widespread distribution for the common ancestor of the family in eastern and western North America, an eastern North American origin having lower statistical support. Of the four hemidactyline clades, only Spelerpini fits the original model of Appalachian origin.

Colonization of Eurasia by Plethodontids and Holarctic History.

Northern hemisphere biogeography has been characterized by major dispersal events between Eurasia and North America, but the routes and timing of such events are debated (39, 40). Allozymic studies favored a divergence time of ≈50 mya between North American and European members of Sg Hydromantes, the NALB being suggested as the dispersal route (9, 13). The recent discovery of Karsenia koreana (10) in northeastern Asia raised new hypotheses including two independent origins: dispersal via Beringia to account for Karsenia, and via the NALB to account for Speleomantes + Atylodes (41). Our data and analyses suggest a different scenario. During the late Cretaceous, diversification of plethodontid lineages occurred rapidly, culminating in ancestors, or the common ancestor, of Karsenia and Sg Hydromantes, which probably diverged from other lineages in western North America. Ancestral range reconstruction (38) gives highest support to this scenario (L = −238.98), but a western North American–eastern Eurasian ancestral range is also statistically significant (L = −239.74). During the late Cretaceous, warm temperate conditions in the northern hemisphere would have facilitated colonization of new habitats and dispersal to far northern latitudes. These environmental changes coupled with geological connections between Eurasia and North America would have shortened transcontinental migration routes. The epicontinental seaway separated eastern and western North America, and the Turgai Sea separated eastern from western Eurasia, making the land bridge that connected western North America and eastern Eurasia (Fig. 2) the most parsimonious scenario for dispersal to Eurasia. We hypothesize a single colonization event followed by rapid diversification in the Holarctic, the split between Karsenia and Sg Hydromantes lineages taking place in Asia just after the K/T boundary (≈65 mya). During the PETM, Eurasia was connected to North America through the Bering land bridge and the NALB (Fig. 2), although by ≈55 mya, the land connection was submerged (42). Our estimate of divergence time between North American Hydromantes and European Speleomantes + Atylodes is ≈41 mya (SI Table 2). The most parsimonious biogeographic scenario from perspectives of paleogeography, divergence time estimates, and the biology of the species (i.e., low dispersal capacity and high degree of philopatry; ref. 11) is that Hydromantes dispersed from northeast Asia both back to western North America and to western Eurasia. Ancestral range reconstruction analyses suggest that the ancestor of Sg Hydromantes was distributed both in western North America and eastern Eurasia (L = −238.76). A distribution only in eastern Eurasia is also statistically significant (L = −240.44). Given the likelihood that the common ancestor of Sg Hydromantes was distributed both in western North America and eastern Eurasia, a final alternative to consider is the origin of Sg Hydromantes in western North America; the ancestor of the European clade might have crossed the Bering land bridge to Asia and western Europe at a later date than the ancestor of Karsenia. This hypothesis is unlikely considering the biological features mentioned above, because it would have required much more dispersal (double the distance of the most likely scenario).

Episodes of Global Change Correspond with Rapid Lineage Diversification.

The diversification of plethodontid lineages occurred during short time spans, no matter what time estimation method is used, as reflected by the short internodes recovered (Fig. 1). Two major episodes of lineage diversification are detected, one in the late Cretaceous and one during the PETM continuing into the Eocene thermal optimum. A similar pattern has been recognized in both birds and mammals (43, 44), with a radiation of major clades in the late Cretaceous followed by a slowing of diversification rate until the PETM, although this was recently challenged for mammals (45) and debate on this issue is still open. Other taxa, including ants and angiosperms, underwent similar diversification episodes (46). The concordance of these events well before and after the end-of-Cretaceous extinctions suggests that they could have been driven by similar factors. Late Cretaceous and PETM experienced global warming events, with significantly higher temperatures in northern latitudes (30, 47). Although global warming may have driven many taxa to extinction, it also may have been a major factor stimulating the diversification of others, generating some uncertainty about what will happen to modern biodiversity under future global warming scenarios. The diversification of angiosperms during Cretaceous warming would have provided new ecological niches suitable for several groups, both vertebrates and invertebrates (26, 44, 46), stimulating their diversification. The spectacular diversification and dispersal of modern groups of mammals and birds also has been linked to rapid global warming during the same periods (48, 49). Global warming periods could have been particularly favorable for dispersal of even the unlikely dispersing salamanders, as well as other tetrapods, and clades of invertebrates and plants, but the causes (i.e., climatic, ecological because of the availability of new resources and niches, or physical by shortening distances) are unknown. Plethodontid salamanders today have a restricted distribution in Eurasia, but they must have been more widespread in the past, leaving open the possibility of new discoveries.

Materials and Methods

Taxon and Gene Sampling.

We sampled all Holarctic plethodontid genera, including Batrachoseps, which is primarily Californian in distribution. Bolitoglossa, representing the neotropical lineage, seven additional salamanders, and six other tetrapods provide a backbone phylogeny and age constraints for divergence dating analyses. Protopterus sp. was used as a general outgroup. Voucher and sequence information are included in SI Table 3. By using standard PCR and sequencing techniques, we obtained sequence data from three nuclear protein-coding genes: 1,459 aligned bp from recombination activating gene 1 (RAG1), 713 aligned bp from brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and 535 aligned bp from proopiomelanocortin (POMC). These markers were selected because (i) they are protein-coding single-copy genes, located in different regions of the nuclear genome, (ii) they vary in degree of conservation, being suitable for deep and shallow phylogenetic inference, and (iii) they are suitable for reconstruction of ancient relationships (50) and for time estimations (51). For primers (52) and sequence parameters see SI Table 4.

Phylogenetic Inference.

We inferred phylogenies using ML and Bayesian inference methods. One thousand nonparametric bootstrap ML repetitions were conducted by using Garli v0.94 (53) under the GTR model, and analyses were repeated three times to test for congruence. We performed analyses using different partition strategies, applying the Akaike Information Criterion to determine the evolutionary models and parameters that best fit each partition (SI Table 4). We performed two independent Bayesian analyses, using a ML starting tree and running four Markov chains sampled every 1,000 generations for 40 million generations with Mr Bayes v3.1 (54). Remaining trees after burnin of 20 million generations were combined, and the 50% majority consensus tree was calculated by using PAUP* 4b10 (55). Alternative placements of some genera were tested with SHT (56). Details on implementing phylogenetic methods are included as (SI Text).

Divergence Dating.

We used Bayesian relative rate tests (57) to test for constancy of evolutionary rates among plethodontids, and to test whether the differences are associated with any major cladogenetic or biogeographic events. To estimate divergence times among clades, we used a relaxed molecular clock Bayesian approach implemented in the package MULTIDIVTIME (20). The potential effects of priors, fossil constraints, and our partitioning strategy were tested by performing multiple analyses with different combinations of parameters. Because the salamander fossil record is uneven, we included several well constrained splits outside amphibians for our divergence time estimation, and used seven calibration events based on amphibian fossils. Because constraining nodes based on the tetrapod fossil record has generated controversy (21, 58), we performed analyses with and without those constraints. Comprehensive information on the divergence dating analyses, fossils, and age constraints used is found in SI Text.

Diversity Estimates and Paleoreconstructions.

Distribution maps (59) were projected to an equal area grid of 0.25 arcmin per cell in ArcInfo, and the species richness (number of species per grid cell) was calculated for all plethodontid genera in the Holarctic. Paleoreconstructions were made of Earth in the Late Cretaceous and the Paleocene/Eocene (Fig. 2; ref. 35), the latter slightly modified to incorporate the NALB (60). In both, sea levels during these periods were estimated (35, 60). Paleotemperature reconstruction is based on a compilation of oxygen isotope measurements of benthic foraminifera, which reflect local temperature changes in their environment (30, 61); paleoclimate (Fig. 2) follows Frakes et al. (62). The mean and 75% confidence intervals were calculated for each 5-million-year period and smoothed in a 2-million-year sliding window. The evolution of geographic ranges using a phylogenetic hypothesis, divergence times, dispersal and extinction rates, and a paleogeographic scenario were modeled in a likelihood framework by using Lagrange 1.0 (38). The method provides likelihood values for the different biogeographic scenarios, enabling reconstruction of ancestral ranges and inference of directionality of dispersal events. A range of extinction and dispersal parameters were explored; see SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Nieto Román, H. B. Shaffer, M. H. Wake, R. Bonett, J. Wiens, P. Chippindale, W. Clemens, J. Patton, two anonymous reviewers, and the D.B.W. laboratory group for discussion and comments, as well as T. Papenfuss for computer support. J. Thorne provided valuable help with Multidivitime, and R. A. Duncan, R. C. Blakey, and C. Scotese helped with Holarctic paleogeography. Tissues were provided by the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Louisiana Museum of Natural History, and G. Nascetti for European species. Laboratory work and fieldwork were supported by National Science Foundation Grant EF-0334939.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. EU275780–EU275901).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705056104/DC1.

References

- 1.AmphibiaWeb: Information on Amphibian Biology and Conservation. [Accessed April 10, 2007]; Available at http://amphibiaweb.org/

- 2.Mueller RL, Macey JR, Jaekel M, Wake DB, Boore JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13820–13825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405785101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macey JR. Cladistics. 2005;21:194–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2005.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chippindale PT, Bonett RM, Baldwin AS, Wiens JJ. Evolution. 2004;58:2809–2822. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiens JJ, Bonett RM, Chippindale PT. Syst Biol. 2005;54:91–110. doi: 10.1080/10635150590906037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiens JJ, Engstrom TN, Chippindale PT. Evolution. 2007;60:2585–2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darlington PJ. Zoogeography: The Geographical Distribution of Animals. New York: Wiley; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wake DB, Maxson LR, Wurst GZ. Evolution. 1978;32:529–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1978.tb04595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanza B, Caputo V, Nascetti G, Bullini L. Mus Reg Sci Nat Monog (Torino) 1995;16:1–366. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min MS, Yang SY, Bonett RM, Vieites DR, Brandon RA, Wake DB. Nature. 2005;435:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature03474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith MA, Green DM. Ecography. 2005;28:110–128. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanza B, Vanni S. Monit Zool Ital. 1981;15:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delfino M, Razzetti E, Salvidio S. Atti Mus Civ Stor Nat “G Doria” Genova. 2005;97:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilder IW, Dunn ER. Copeia. 1920;1920:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wake DB. Mem So Calif Acad Sci. 1966;4:1–111. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruben JA, Boicot AJ. Am Nat. 1989;134:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiens JJ, Parra-Olea G, García-París M, Wake D. Proc R Soc B. 2007;274:919–928. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromham L, Penny D. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:216–224. doi: 10.1038/nrg1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graur D, Martin W. Trends Genet. 2004;20:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorne JL. Raleigh: Department of Genetics and Statistics, North Carolina State University; 2003. MULTIDIVTIME v9/25/03. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller J, Reisz RR. BioEssays. 2005;27:1069–1075. doi: 10.1002/bies.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vences M, Vieites DR, Glaw F, Brinkmann H, Kosuch J, Veith M, Meyer A. Proc R Soc B. 2003;270:2435–2442. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.San Mauro D, Vences M, Alcobendas M, Zardoya R, Meyer A. Am Nat. 2005;165:590–599. doi: 10.1086/429523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang P, Chen YQ, Zhou H, Liu YF, Wang XL, Papenfuss TJ, Wake DB, Qu LH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7360–7365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602325103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar S, Hedges SB. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roelants K, Coger DJ, Wilkinson M, Loador SP, Biju SD, Guillaume K, Moriau L, Bossuyt F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:887–892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608378104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marjanovic D, Laurin M. Syst Biol. 2007;56:369–388. doi: 10.1080/10635150701397635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milner AR. In: The Fossil Record 2. Benton MJ, editor. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 665–679. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao K, Shubin NS. Nature. 2003;422:424–429. doi: 10.1038/nature01491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K. Science. 2001;292:686–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1059412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reagan NL, Verrell PA. Am Nat. 1991;138:1307–1313. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beachy CK, Bruce RC. Am Nat. 1992;139:839–847. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruben JA, Reagan NL, Verrell PA, Boucot AJ. Am Nat. 1993;142:1038–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruce RC. Herpetol Rev. 2005;36:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scotese CR. Arlington, Texas: PALEOMAP Project; 2001. Earth System History Geographic Information System. Version 02b. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrixson BE, Bond JE. Mol Phyl Evol. 2007;42:738–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozak KH, Weisrock DW, Larson A. Proc R Soc B. 2005;273:539–546. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ree RH, Moore BR, Webb CO, Donoghue MJ. Evolution. 2005;59(11):2299–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donoghue MJ, Smith SA. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2004;359:1633–1644. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanmartin I, Enghoff H, Ronquist F. Biol J Linn Soc. 2001;73:345–390. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanza B, Pastorelli C, Laghi P, Cimmaruta R. Atti Mus Civ Stor Nat Trieste. 2006;52:5–135. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storey M, Duncan RA, Swisher CC., III Science. 2007;316:587–589. doi: 10.1126/science.1135274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ericson PGP, Anderson CL, Britton T, Eizanowski A, Johansson US, Källersjo M, Ohlson JI, Parsons TJ, Zuccon D, Mayr G. Biol Lett. 2006;2:543–547. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bininda-Edmonds ORP, Cardillo M, Jones KE, MacPhee RDE, Beck RMD, Grenyer R, Price SA, Vos RA, Gittleman JL, Purvis A. Nature. 2007;446:507–512. doi: 10.1038/nature05634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wible JR, Rougier GW, Novacek MJ, Asher RJ. Nature. 2007;447:1003–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature05854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreau CS, Bell CD, Vila R, Archibald SB, Pierce NE. Science. 2006;312:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1124891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkyns HC, Forster A, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damste JS. Nature. 2004;432:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nature03143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gingerich PD. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith T, Rose KD, Gingerich PD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11223–11227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511296103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Springer MS, DeBry RW, Douady C, Amrine HM, Madsen O, de Jong WW, Stanhope MJ. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:132–143. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glazko GV, Nei M. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:424–434. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiari Y, Vences M, Vieites DR, Rabemananjara F, Bora P, Ramilijaona O, Meyer A. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:3763–3774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwickl DJ. PhD dissertation. Austin: Univ of Texas; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2002. Version 4.b10. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimodaira H, Hasegawa M. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1114. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilcox TP, García de Leon FJ, Hendrickson DA, Hillis DM. Mol Phyl Evol. 2004;31:1101–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hedges SB, Kumar S, Tuinen MV. BioEssays. 2006;28:770–771. doi: 10.1002/bies.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Conservation Union (IUCN), Conservation International, and NatureServe. Global Amphibian Assessment [World Conservation Union (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland; Conservation International, Arlington, VA; and NatureServe, Arlington, VA] 2006 www.globalamphibians.org. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ziegler PA. Am Assoc Pet Geol Mem. 1988;43:164–196. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Veizer J, Ala D, Azmy K, Bruckschen P, Buhl D, Bruhn F, Carden GAF, Diener A, Ebneth S, Godderis Y, et al. Chem Geol. 1999;161:59–88. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frakes LA, Francis JE, Syktus JL. Climate Modes of the Phanerozoic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.