Abstract

The ε subunit of the human endplate ACh receptor (AChR) is a key determinant of the large fraction of the ACh-evoked current carried by Ca2+ ions (Pf). Consequently, missense mutations in the ε subunit are potential targets for altering the Pf of human AChR. In this paper we investigate the effects of two pathogenic point mutations in the M2 transmembrane segment AChR ε subunit, εT264P and εV259F, that cause slow-channel syndromes (SCS). When expressed in GH4C1 cells, the mutant receptors subunits raise Ca2+ permeability of the receptors ∼1.5 and ∼2-fold above that of wild-type, to attain Pf values of 11.8% (εT264P) and 15.4% (εV259F). The latter value exceeds most Pf values reported to date for ligand-gated ion channels. Consistent with these findings, the biionic Ca2+ permeability ratio (PCa/PCs) of the mutant AChRs is also increased. Upon repetitive stimulation with ACh, the mutant receptors show an enhanced current run-down compared with wild-type, leading to a strong reduction of their function. We propose that the enhanced Ca2+ permeability of the mutant receptors overrides the protective effect of desensitization and, together with the prolonged opening events of the AChR channel, is an important determinant of the excitotoxic endplate damage in the SCS.

Slow-channel syndromes (SCS) are caused by point mutations in the human endplate acetylcholine receptor (AChR) that greatly prolong the openings of the AChR channel. In a peculiar form of the SCS, tubulofilamentous inclusions, similar to those found in inclusion body myositis (IBM), accumulate in junctional regions of the muscle fibres (Fidzianska et al. 2005). This SCS is caused by a valine-to-phenylalanine substitution at position 259 in the M2 transmembrane segment of the AChR ε subunit (εV259F) that lines the channel pore.

Hyperphosphorylation of tau protein leads to formation of tubulofilamentous structures in neuronal diseases as well as in IBM, and is associated with, and possibly caused by, a disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis (LaFerla, 2002; Pierrot et al. 2004). We recently showed that the fractional Ca2+ current (Pf) of human endplate AChR, defined as the percentage of the total ACh-evoked current carried by Ca2+ ions, is twice as large than that of the homologous mouse AChR (Fucile et al. 2006). The high Ca2+ permeability of human AChR by itself enhances vulnerability of the human endplate to excitotoxic damage (endplate myopathy) in the SCS. An increased fractional Ca2+ current would further contribute to Ca2+ overloading of the postsynaptic region and to the Ca2+-dependent pathological effects. Since the human ε subunit turned out to be a key determinant of the high Pf at the human endplate (Fucile et al. 2006), we postulated that strategically positioned amino acid substitutions in the ε subunit can alter the Ca2+ permeability of the AChR channel.

To test this notion, we measured the Pf of the εV259F-AChR and found it almost twice as high as that of wild-type (WT) AChR. To determine whether this effect is mutation specific, we also examined the Pf for another well-characterized SCS mutation in the M2 segment of the ε subunit, εT264P (Ohno et al. 1995). We found that the Pf of the εT264P-AChR is also markedly increased compared with that of the WT receptor. Our results provide the first direct evidence that mutations associated with SCS alter Ca2+ permeability as well as channel kinetics of the human endplate AChR.

Methods

Cell cultures and transfection

Rat pituitary GH4C1 cells were grown (5% CO2, 37°C) in HAM F10 medium plus 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were plated onto 35 mm Petri dishes (3 × 105 cells per dish) 24 h prior to transfection. The cDNAs encoding human wild-type α, β, δ, ε subunits, or ε subunits harbouring the εT264P or εV259F mutations were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000, using 1 μg of cDNA for each subunit per Petri dish. Medium was changed after overnight incubation with cDNAs, and experiments carried out after a further 24–48 h. All media were purchased from Invitrogen.

Solutions and chemicals

Cells were superfused with a standard external medium containing (mm): 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes-NaOH, 10 glucose, pH 7.3. For cell-attached experiments, patch pipettes were filled with the same solution plus ACh (200 nm).

For whole-cell recordings, patch pipettes were filled with a solution containing (mm): 120 KCl, 5 BAPTA, 10 Hepes-KOH, 2 Mg-ATP, 2 MgCl2, pH 7.3.

For Pf determinations, intracellular solution contained (mm): 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG), 10 Hepes-HCl, 0.25 Fura-2 pentapotassium salt, 0.001 thapsigargin, pH 7.3. Calibration measurements were performed using an extracellular solution made of (mm): 153 NMDG, 10 CaCl2, 10 Hepes-HCl, pH 7.3.

The shift of the reversal potential of ACh-evoked current was measured using an intracellular solution containing (mm): 140 CsCl, 10 Hepes-CsOH, 20 BAPTA, pH 7.3. The external solution contained (mm): 150 CsCl, 10 Hepes-CsOH, 10 glucose, pH 7.3 plus 1 or 10 CaCl2.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (USA), except for Fura-2 pentapotassium salt (Molecular Probes).

Electrophysiology

Currents were recorded using borosilicate glass patch pipettes (2–5 MΩ tip resistance, Sylgard-coated for single-channel recordings) and an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). Data were recorded and analysed using pCLAMP 9 (Molecular Devices). All recordings were performed at 25–27°C.

For whole-cell recordings, series resistance was compensated by 80–90%. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of −60 mV and continuously superfused using a gravity-driven fast exchanger perfusion system (RSC-200, BioLogique, France). Current decay and run-down were fitted with single exponential curves [i(t) =i∞+i0e−t/τ], using Origin 7 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

The relative Ca2+ permeability in biionic conditions (PCa/PCs) was estimated from the shift of the reversal potential (Vrev) of whole-cell ACh-induced current using two different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Cao1 of 1 mm, Cao10 of 10 mm). In each cell, Vrev was calculated at both Ca2+ concentrations (Vr1 and Vr10, respectively), by linear interpolation of the ACh-evoked currents peak amplitude plotted versus the test potential. The use of voltage ramp yielded inaccurate results because of the rapid desensitization of εV259F-AChR. PCa/PCs ratios were obtained from the extended Lewis equation adapted to the chosen ion concentrations (Lewis, 1979; Castro & Albuquerque, 1995):

| (1) |

where F, R, T are the usual thermodynamic constants and Vr= Vr10− Vr1, Ion activity as given by Castro & Albuquerque (1995), was used in calculations. Membrane potential was stepped to the test potential 1 s before ACh application.

ACh dose–current curves were constructed applying to each cell different doses of transmitter (0.1–300 μm, applied at 30–60 s interval) and normalizing the current response to the plateau value. The data were best-fitted using Hill equation by Origin 7 software (Origin Laboratory).

Single-channel data were filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 25 kHz. Analysis was performed with a 50% threshold criterion, omitting events shorter than 0.12 ms. Slope conductance was calculated by linear fitting of the unitary amplitudes recorded at different pipette potentials (at least three for each cell). The fit was extrapolated to estimate cell resting potential, which was summed to the pipette potential to obtain membrane potential. The critical time used to identify a burst, determined for each cell from the closed time distribution (Colquhoun & Sakmann, 1985), ranged between 1 and 4 ms.

All results are given as mean ±s.e.m. Two data sets were considered statistically different when P < 0.05 (ANOVA test).

Pf determination

The methods to measure Pf have been fully reported previously (Fucile et al. 2000, 2006). Fluorescence determinations were made using a fluorescence upright microscope (Axioskop 2, Zeiss, Germany), a digital 12-bit cooled camera (SensiCam, PCO, Germany) and a monochromator (Cairn, UK). The system was driven by Axon Imaging Workbench 2 software (Molecular Devices), which also triggered the start of electrophysiological recording. All optical parameters and the setting of the digital camera (50 ms exposure time, 4 × 4 binning) were maintained throughout all measurements. The changes in intracellular calcium were monitored at a single excitation wavelength (380 nm), to achieve a higher time resolution, and expressed as the ratio of time-resolved fluorescence variation over the basal fluorescence (ΔF/F0).

Only isolated cells with low basal intracellular Ca2+ (F340/F380 ratio values < 2) were considered for recordings. Cells were filled with Fura-2 pentapotassium salt through the patch pipette and measurements performed after obtaining a stable value of basal fluorescence, with F380 > 200 arbitrary units (a.u), indicating satisfactory loading. The ratio F/Q (expressed in nC−1) was defined as:

where INic is the nicotine-evoked whole-cell current. The charge entered into the cell was calculated at each fluorescence acquisition time. The F/Q ratio was estimated for each cell as the slope of the linear fit of the F versus Q plot. Pf was determined normalizing the F/Q ratio to the calibration value, obtained in a calibration medium containing only Ca2+ as permeant ions:

The F/Qcalibration value obtained in this work was 6.6 ± 1.9 nC−1 (mean ±s.e.m., n = 4 cells).

Results

Characterization of the εV259F and εT264P AChRs in GH4C1 cells

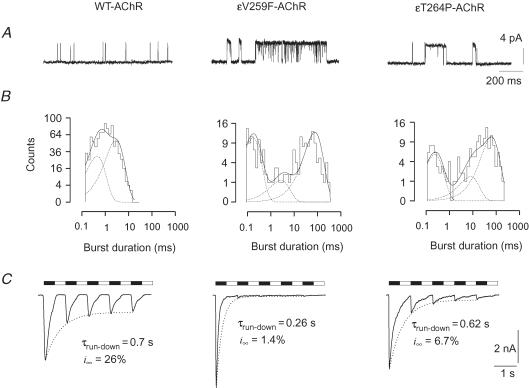

We first determined the main functional characteristics of wild-type (WT) and mutant AChRs expressed in GH4C1 cells. We confirmed the slow-channel properties of both εV259F- and εT264P-AChR at the single-channel level by cell-attached recordings (Fig. 1A). For the WT-AChR, the mean single channel slope conductance was about 50 pS and the mean burst duration was 1.9 ms (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1B (left), the distribution of burst duration was fitted by two exponential components, with the mean time constants (τb1 and τb2) and weights given in Table 1. The duration of the bursts was greatly enhanced by the εV259F as well as the εT264P mutation, while the conductance of unitary events was not significantly affected (Table 1). The distribution of burst durations presented a third exponential component (time constant, τb3) for both mutant AChRs. Typical examples are shown in Fig. 1B (middle and right panels) and mean values of the τbs reported in Table 1. These data confirm that both mutant receptors retain their main functional properties when expressed in GH4C1 cells.

Figure 1.

Functional characterization of WT and mutant AChRs in GH4C1 cells A, typical cell-attached recordings of channel openings evoked by ACh (200 nm) in cells transfected with WT or mutant AChRs, as indicated, revealing prolonged burst duration in εV259F and εT264P mutant AChRs. Traces were filtered at 1 kHz for display (5 kHz for analysis). Unitary conductance was: 49.8 pS (WT), 46.0 pS (εV259F) and 46.6 pS (εT264P). B, distribution of burst durations for the same recordings as in A, best fitted with the sum of two or three exponential components (dotted lines). Time constants (weight) of the fitting distributions in these three cells (at −100 mV membrane potential) were: for WT-AChR, τb1= 0.46 ms (42%), τb2= 2.9 ms (58%), critical τ= 4 ms; for εV259F, τb1= 0.17 ms (41%), τb2= 2.7 ms (14%), τb3= 78 ms (45%), critical τ= 4 ms; for εT264P, τb1= 0.24 ms (34%), τb2= 7.9 ms (18%), τb3= 63 ms (48%), critical τ= 1 ms. C, typical whole-cell responses to repetitive ACh (100 μm for 0.5 s) applications (black bars) in cells transfected as indicated. Dotted lines represent the exponential fit of the current peaks with the parameters given on each panel, showing the enhanced run-down of mutant AChRs. Holding potential, −60 mV. Open bars indicate superfusion with standard solution.

Table 1.

Single channel properties of WT and mutant AChRs

| WT-AChR | εV259F-AChR | εT264P-AChR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductance (pS) | 48.6 ± 2.4 (7) | 49.7 ± 1.7 (7) | 51.1 ± 2.6 (4) |

| Burst duration (ms) | 1.88 ± 0.19 (5) | 47 ± 11 (4) | 42.4 ± 7.6 (4) |

| Critical time (ms) | 3.4 ± 0.6 (5) | 5 ± 1 (4) | 1.8 ± 0.7 (4) |

| τb1 (ms)/weight (%) | 3.2 ± 0.3/49 ± 5 (5) | 3.2 ± 0.3/32 ± 3 (4) | 3.2 ± 0.3/33 ± 4 (4) |

| τb2 (ms)/weight (%) | 3.2 ± 0.3/51 ± 5 (5) | 3.7 ± 2/18 ± 8 (4) | 3.2 ± 0.3/17 ± 9 (4) |

| τb3 (ms)/weight (%) | not present | 73 ± 10/50 ± 6 (4) | 74 ± 14/50 ± 6 (4) |

Data are given as mean ±s.e.m. (number of cells). Burst analysis was performed on cell-attached recordings obtained with bandwidth of 5 kHz; T = 25–27°C, with an estimated membrane potential of −90 to −105 mV (as determined a posteriori by the i–V relation). τb1, τb2, τb3: time constants of the exponential components best fitting the distribution of burst durations.

At the macroscopic level, the amplitude of the ACh-evoked currents showed large cell-to-cell variation, ranging from −0.2 nA to over −10 nA at −60 mV (ACh, 100 μm) for each type of AChR, suggesting that expression of the mutant AChRs was not appreciably impaired compared with that of WT-AChR. Both mutant receptors had a higher apparent affinity for ACh, as dose–response curves showed a decrease of the EC50 from 33.5 ± 1.4 μm (n = 4) in the WT-AChR, to 1.2 ± 0.2 μm (n = 4) and 0.9 ± 0.2 μm (n = 5) for εV259F-AChR and εT264P-AChR, respectively (data not shown).

During sustained ACh application, whole-cell currents decayed exponentially, reflecting receptor desensitization. At the plateau concentration of 100 μm, the rate of decay was similar for the WT-AChR (τdecay= 207 ± 28 ms, n = 14) and the εT264P-AChR (246 ± 37 ms, n = 7; P = 0.4), whereas the εV259F-AChR showed a faster decay (128 ± 16 ms, n = 10; P = 0.04). Repetitive ACh applications produced currents with decreasing peak amplitude (current run-down) for all three AChRs examined (Fig. 1C). An exponential fit of the consecutive current peaks showed that WT-AChR (Fig. 1C, left) had a relatively slow and limited run-down (τrun-down= 0.78 ± 0.08 s, n = 14), with an asymptotic amplitude (i∞) of 31 ± 4% of the first response. For the εV259F mutant (Fig. 1C, middle), the decay was both faster (τrun-down= 0.38 ± 0.06 s, n = 9, P = 0.002) and more pronounced (i∞= 4.5 ± 0.9%) than for WT-AChR. The εT264P mutant AChR (Fig. 1C, right) showed an intermediate behaviour, with a τrun-down= 0.68 ± 0.05 s (n = 7) and an asymptote at i∞= 9 ± 2%, significantly less than that of WT-AChR (P = 0.001). Current run-down was not accompanied by an increased rate of desensitization, as, in each cell, the τdecay of the third current response was not significantly different from that of the first response (P > 0.5). Together, these data indicate that the mutant receptors become less responsive than WT, or unresponsive, to ACh at physiological rates of stimulation.

Pf and PCa/PCs measurements

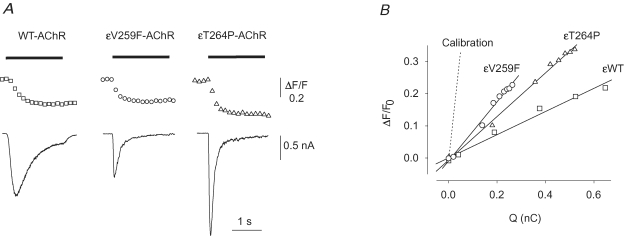

For Pf determinations we used nicotine because ACh might activate muscarinic receptors, leading to Ca2+ release from internal stores. Currents evoked by nicotine (100 μm) were comparable to those elicited by ACh, except for a slower current decay observed for the WT-AChR (τdecay= 649 ± 87 ms, n = 14) (e.g. Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Calcium fractional current of WT and mutant AchRs A, typical fluorescence (top trace) and current (bottom) responses to nicotine (100 μm, horizontal bar) simultaneously recorded in cells expressing the indicated AChR. Notice the large Ca2+ response recorded in the εV259 cell in spite of a relatively small current. B, linear fit of the ΔF/F0versus Q in the same three cells as in A. The dotted line represents the averaged slope of the calibration experiments. ^, εV259F-AChR; ▵, εT264P-AChR; □, WT-AChR, as indicated.

Nicotine-evoked Ca2+ and current (INic) responses were simultaneously recorded (Fig. 2A), and the F/Q ratios calculated (Fig. 2B). In cells expressing WT-AChR (e.g. Fig. 2A, left), normalization to calibration values yielded Pf values of 7.83 ± 0.69% (n = 11), in excellent agreement with previously published values (Fucile et al. 2006). The Pf value measured for εV259F-AChR (Fig. 2A, middle) was 15.4 ± 1.7% (n = 12, P = 0.0007), showing that this mutation doubles the Ca2+ permeability of the AChR-channel. For comparison, we measured the Pf of the εT264P-AChR (Fig. 2A, right) and again found a significantly enhanced Ca2+ permeability (Pf= 11.76 ± 0.91%, n = 13, P = 0.003). Thus, both slow-channel mutations in the M2 segment of the ε subunit enhance the Ca2+ permeability of human AChR.

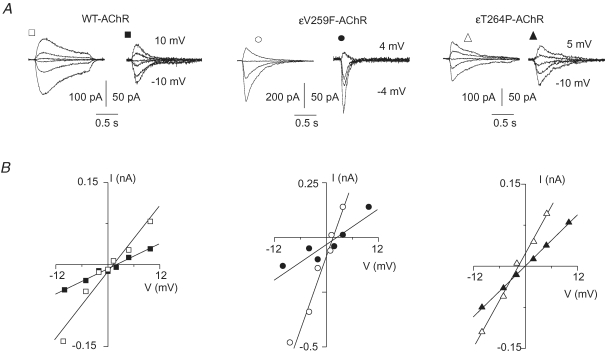

To test by a different approach that the Ca2+ permeability of the mutant AChRs was enhanced compared with that of WT-AChR, we also assessed the relative Ca2+ permeability of each isoform by measuring its biionic permeability ratio PCa/PCs. The currents evoked by ACh (10 μm) were measured at five or more test potentials between −10 and +10 mV, bracketing the current reversal potential, at two different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (1 mm and 10 mm) (Fig. 3A). With 1 mm extracellular Ca2+, the average values of the reversal potentials were not statistically different for the εV259F-AChR (0.2 ± 0.6 mV, n = 7) or the εT264P-AChR (−0.5 ± 0.3 mV, n = 10) versus the WT-AChR (0.1 ± 0.3 mV, n = 8; P > 0.2). The higher extracellular Ca2+ concentration induced a right-shift of the reversal potential of each isoform (Fig. 3B). Using eqn (1) (see Methods), we obtained PCa/PCs= 0.73 ± 0.07 (n = 7) for the WT-AChR. The value of PCa/PCs obtained for the εV259F-AChR (1.20 ± 0.20, n = 5) was significantly larger than that of WT-AChR (P = 0.038). A further increase over the WT-AChR value was observed in the PCa/PCs ratio determined for the εT264P-AChR (1.35 ± 0.10, n = 7, P = 0.0007).

Figure 3.

Relative Ca2+ permeability (PCa/PCs) of WT and mutant AchRs A, ensemble whole-cell currents recorded in response to ACh (10 μm) applied at various test potentials with low extracellular Ca2+ (1 mm, open symbols) or high extracellular Ca2+ (10 mm, filled symbols), in transfected cells expressing the indicated AChRs. In each panel, numbers refer to the most positive and negative test potentials shown. Note the reduction of current amplitude in high Ca2+ for all the AChR isoforms. B, current peak amplitude plotted versus membrane test potential in the same cells as in A. Lines represent the linear fit of each data group. Note positive shifts of current reversal potentials (0.7 mV for WT-AChR; 1.5 mV for εV259F-AChR; 1.6 mV for εT264P-AChR) at 10 mm Ca2+ (filled symbols).

Discussion

This paper provides the first quantitative evidence that the Ca2+ permeability of the human endplate AChR can be modified by point mutations in the membrane-spanning M2 segment of the ε subunit. The mutations examined, εV259F and εT264P, gave rise to a fractional Ca2+ current of ∼15% and ∼12%, respectively. These Pf values are among the highest known, being equivalent to, or higher than, those reported for the NMDA receptor (up to 11%, Burnashev et al. 1995; 13.5%, Jatzke et al. 2002), or the homomeric α7-AChR (11.4%, Fucile et al. 2003).

The enhanced Ca2+ permeability of the ε SCS mutants additionally increases the Ca2+ ingress into the junctional sarcoplasm that stems from the prolonged duration of the synaptic current and the intrinsically high Ca2+ permeability of human AChR and is thus directly relevant to the pathogenesis of the endplate myopathy associated with the observed mutations. An increased permeability to Ca2+ may also occur with SCS mutations in other AChR subunits, as an increase of PCa/PCs was observed in HEK 293 cells expressing mouse βV299F-AChR, a mutant receptor designed after a recently identified mutation in a SCS patient (Navedo et al. 2006). Both εV259F and εT264P mutations yield a complex effect on receptor function. The affinity of the mutant receptors for ACh is increased by about one order of magnitude, but this increase is accompanied by (or possibly results in) a loss of receptor function upon repetitive stimulation at high ACh concentration, as well as an enhanced rate of desensitization in the case of the εV259F-AChR. That both mutant AChRs show an increased run-down during repetitive exposure to ACh probably contributes to the abnormal fatigability on exertion observed in vivo. Interestingly, the propensity of the mutant receptors to become unresponsive could partially mitigate the adverse effects of the prolonged open time and increased Ca2+ permeability of the mutant channels, but not enough to protect the endplate from excitotoxic injury.

In the only patient carrying the εV259F mutation identified to date (Fidzianska et al. 2005), the endplate myopathy was accompanied by the presence of tubulofilamentous inclusion bodies. The formation of these structures might be precipitated by the severe disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis caused by the concurrent prolongation of synaptic events and doubled Pf, consistent with the notion that an altered Ca2+ homeostasis enhances phosphorylation of tau protein and formation of fibrillary structures (LaFerla, 2002).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the ε subunit is a key determinant of the Ca2+ permeability of adult muscle AChR. The Pf is almost 2-fold higher in AChRs containing the ε rather than the γ subunit (Villarroel & Sakmann, 1996; Ragozzino et al. 1998). Moreover, the ε subunit is the only determinant of the high Ca2+ permeability of the human adult AChR (Fucile et al. 2006). That a valine-to-phenylalanine mutation in the pore-forming M2 segment of the ε subunit (εV259F) markedly enhances Pf whereas mutation of the corresponding residue in the α subunit (αV249F) has no effect on Pf (Fucile et al. 2006), is also consistent with the important role of the ε subunit in governing the Ca2+ permeability of the human receptor. Another mutation in the ε M2 segment, εT264P, also increases the Pf of the mutant receptor. Thus, the data presented here confirm that the ε subunit has a strong effect on the Ca2+ permeability of human endplate AChR.

In our experiments, the alterations in PCa/PCs values only partially mirrored those in the Pf. The rapid run-down of current generated by εV259F-AChR during multiple applications of ACh limits the accuracy of the PCa/PCs measurements. Furthermore, constant field assumptions leading to eqn (1) may not hold under the actual experimental conditions, as previously reported (Vernino et al. 1994; Burnashev et al. 1995). For instance, studies that compare muscle and neuronal AChRs reveal a 7-fold difference in the PCa/PCs ration (Vernino et al. 1994), but only a 2-fold difference for the Pf values (Vernino et al. 1993). Thus, biionic permeability ratios often provide qualitative rather than quantitative estimates of the relative Ca2+ permeability of a given channel whereas Pf determinations require no a priori assumptions (Zhou & Neher, 1994) and thus yield a more reliable measure of the Ca2+ permeability of the AChR channel (Burnashev et al. 1995).

In conclusion, our studies provide further insight into the pathogenic mechanisms whereby single amino acid substitutions in AChR subunits cause disease, which results from the delicate balance between the deleterious effects of the increased Ca2+ permeability and the dampening of the synaptic response by run-down of the investigated SCS mutant receptors at physiological rates of stimulation, by loss of AChR from the degenerating folds, and by the altered endplate geometry.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Ministero Istruzione Universita' e Ricerca to F.E. and F.G.; by a grant from Ministero della Salute (Doping 2005) to F.E. and F.G. and by NIH Grant NS6277 and a Muscular Dystrophy Association Grant to A.G.E. A.DiC. is supported by the PhD programme in Neurophysiology of Universita' La Sapienza.

References

- Burnashev N, Zhou Z, Neher E, Sakmann B. Fractional calcium currents through recombinant GluR channels of the NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J Physiol. 1995;485:403–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro NG, Albuquerque EX. α-Bungarotoxin-sensitive hippocampal nicotinic receptor channel has a high calcium permeability. Biophys J. 1995;68:516–524. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80213-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sakmann B. Fast events in single-channel current activated by acetylcholine and its analogues at the frog muscle end-plate. J Physiol. 1985;369:501–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidzianska A, Ryniewicz B, Shen X-M, Engel AG. IBM-type inclusions in a patient with slow-channel syndrome caused by a mutation in the AChR epsilon subunit. Neuromuscular Dis. 2005;15:753–759. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S, Palma E, Mileo AM, Miledi R, Eusebi F. Human neuronal threonine-for-leucine-248 α7 mutant nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are highly Ca2+ permeable. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3643–3648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050582497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S, Renzi M, Lax P, Eusebi F. Fractional Ca2+ current through human neuronal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S, Sucapane A, Grassi F, Eusebi F, Engel AG. The human adult subtype ACh receptor has high Ca2+ permeability and predisposes to endplate Ca2+ overloading. J Physiol. 2006;573:35–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatzke C, Watanabe J, Wollmuth LP. Voltage and concentration dependence of Ca2+ permeability in recombinant glutamate receptor subunits. J Physiol. 2002;538:25–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM. Calcium dyshomeostasis and intracellular signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:862–872. doi: 10.1038/nrn960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CA. Ion-concentration dependence of the reversal potential and the single channel conductance of ion channels at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1979;286:417–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navedo MF, Lasalde-Dominicci JA, Baez-Pagan CA, Diaz-Perez L, Rojas LV, Maselli RA, Staub J, Schott K, Zayas R, Gomez CM. Novel β subunit mutation causes a slow-channel syndrome by enhancing activation and decreasing the rate of agonist dissociation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Hutchinson DO, Milone M, Brengman JM, Bouzat C, Sine SM, Engel AG. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by prolonged acetylcholine channel openings due to a mutation in the M2 domain of the epsilon subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:758–762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot N, Ghisdal P, Caumont AS, Octave JN. Intraneuronal amyloid-β 1-42 production triggered by sustained increase of cytosolic calcium concentration induces neuronal death. J Neurochem. 2004;88:1140–1150. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino D, Barabino B, Fucile S, Eusebi F. Ca2+ permeability of mouse and chick nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in transiently transfected human cells. J Physiol. 1998;507:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.749bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Amador M, Luetje CW, Patrick J, Dani JA. Calcium modulation and high calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90114-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Rogers M, Radcliffe KA, Dani JA. Quantitative measurements of calcium flux through muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5514–5524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05514.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroel A, Sakmann B. Calcium permeability increase of endplate channels in rat muscle during postnatal development. J Physiol. 1996;496:331–338. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Neher E. Calcium permeability of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Pflugers Arch. 1993;425:511–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00374879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]