Abstract

Large conductance, Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+ (BK) channels are exquisitely regulated to suit their diverse roles in a large variety of physiological processes. BK channels are composed of pore-forming α subunits and a family of tissue-specific accessory β subunits. The smooth muscle–specific β1 subunit has an essential role in regulating smooth muscle contraction and modulates BK channel steady-state open probability and gating kinetics. Effects of β1 on channel's gating energetics are not completely understood. One of the difficulties is that it has not yet been possible to measure the effects of β1 on channel's intrinsic closed-to-open transition (in the absence of voltage sensor activation and Ca2+ binding) due to the very low open probability in the presence of β1. In this study, we used a mutation of the α subunit (F315Y) that increases channel openings by greater than four orders of magnitude to directly compare channels' intrinsic open probabilities in the presence and absence of the β1 subunit. Effects of β1 on steady-state open probabilities of both wild-type α and the F315Y mutation were analyzed using the dual allosteric HA model. We found that mouse β1 has two major effects on channel's gating energetics. β1 reduces the intrinsic closed-to-open equilibrium that underlies the inhibition of BK channel opening seen in submicromolar Ca2+. Further, PO measurements at limiting slope allow us to infer that β1 shifts open channel voltage sensor activation to negative membrane potentials, which contributes to enhanced channel opening seen at micromolar Ca2+ concentrations. Using the F315Y α subunit with deletion mutants of β1, we also demonstrate that the small N- and C-terminal intracellular domains of β1 play important roles in altering channel's intrinsic opening and voltage sensor activation. In summary, these results demonstrate that β1 has distinct effects on BK channel intrinsic gating and voltage sensor activation that can be functionally uncoupled by mutations in the intracellular domains.

INTRODUCTION

Large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BK-type potassium channel) are activated by intracellular Ca2+ and depolarizing voltages. When open, BK channels have a very large outward potassium conductance (∼250 pS) and are therefore very effective in hyperpolarizing the membrane. The coincident activation of BK channels by Ca2+ and voltage makes these channels uniquely tailored to regulate voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in a number of cell types (Kaczorowski et al., 1996; Gribkoff et al., 1997; Calderone, 2002). BK channels in smooth muscle use the accessory β1 subunit to promote channel opening (Knaus et al., 1994; Tanaka et al., 1997). Previously the important role of the β subunit has been demonstrated by targeted gene knockout of the β1 locus in mice. Knockout mice have BK channels with reduced openings, increased vascular tone, and hypertension (Brenner et al., 2000b; Pluger et al., 2000).

BK channel open probability is dependent on its intrinsic closed to open equilibrium that is described by the equilibrium constant L (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). This is the inherent PO of the channel without influence of other gating mechanisms. BK channel gating is also allosterically coupled to voltage sensor activation and Ca2+ binding (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). A prominent effect of β1 subunits is an increase in BK channel openings. However it is not well established how, and to what degree β1 subunit effects on L, voltage sensor activation, or Ca2+ binding contribute to enhanced PO.

Historically, because β1 causes a negative voltage shift of the conductance–voltage (G-V) relationship, in a manner similar to increased Ca2+, the effects of the β1 subunit was first described as an “increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity” (McManus et al., 1995; Dworetzky et al., 1996; Meera et al., 1996). Later, it was found that this effect may not be due exclusively to changes in Ca2+ binding equilibrium (Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Nimigean and Magleby, 2000; Bao and Cox, 2005; Orio and Latorre, 2005). Using gating current measurements, Bao and Cox clearly demonstrated that the bovine β1 subunit shifts voltage sensor activation to more negative membrane potentials, and this may account for β1 enhanced openings (Bao and Cox, 2005). Orio and Latorre (2005) also suggested that human β1 shifts open channel voltage sensor activation to more negative membrane potentials. Effects of β1 on channel's intrinsic gating are less clear. Whereas Orio and Latorre proposed that human β1 reduces channel's intrinsic equilibrium (L) for opening, Bao and Cox suggested otherwise for the bovine β1.

Based on HA model for BK channel gating (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002), it is advantageous to directly compare α and α+β1 under conditions that isolate the influence of intrinsic gating. This is accomplished by measuring ionic current at 0 Ca2+ (to exclude effects on Ca2+ binding) and very negative membrane potentials (the limiting slope, to exclude effects on voltage sensor activation). Measurement at higher voltages can then indicate the contribution of voltage sensor activation. This approach has proven useful for evaluating BK channel α subunits alone (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Ma et al., 2006). However, under such conditions, β1 channel openings fall below detection levels and this approach has not been feasible (Bao and Cox, 2005; Orio and Latorre, 2005).

Here, we have used a previously described α subunit mutation (F380Y in human cDNA) (Lippiat et al., 2000) that increases channel openings to investigate β1 subunit effects on channel gating. This allows, for the first time, measurement of α+β1 PO in the absence of Ca2+ and voltage sensor activation. Analysis of PO-V relationships using the dual allosteric HA gating model revealed that the β1 subunit confers two opposing effects on channel openings; both a negative voltage shift for voltage sensor activation (VhO) that contributes to increased channel openings seen in micromolar Ca2+, and a reduced closed to open equilibrium (L0) that contributes to reduced channel openings seen in submicromolar Ca2+. Further, deletion analysis demonstrates that interactions at the small intracellular domains mediate intrinsic and voltage-dependent gating effects of β1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patch Clamp Recording β1 Subunit Mutants

To study channel functional properties, mouse β1 cDNAs (Brenner et al., 2000a) and mouse α cDNAs (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no. MMU09383) were cotransfected into HEK293 cells. The F380Y mutation, originally described in the human cDNA (Lippiat et al., 2000), was introduced in the mouse α subunit cDNA (site is F315Y in mouse) using the Stratagene Quick-Change Mutagenesis kit.

Mouse β1 mutants were generated by PCR amplification of the β1 cDNAs with amplification primers that delete the N-terminal residues KKLVMAQKRGE (residues 3–13) and C-terminal residues NRSLSILAAQK (residues 181–191) for β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11, respectively. The double mutant, β1ΔN10ΔC11 differs in that the E13 residue was not deleted. Using a C-terminal epitope-tagged β1ΔN11ΔC11, immunostaining showed expression. However, electrophysiology recordings showed no evidence of functional interactions with BK α subunits using stimulus protocols and a broad range of calcium as in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The mβ1 subunit promotes BK channel activation in high Ca2+ and reduces channel activation in low Ca2+. (A) Left, families of BK/α currents evoked by 40-ms depolarizations (20-mV steps over the indicated range) in 7 μM Ca2+. Right, normalized G-V relationships (mean ± SEM) of BK/α at indicated Ca2+ (n = 12–44). (B) Left, families of BK/α+β1 currents evoked by 40-ms depolarizations (20-mV steps over the indicated range) in 7 μM Ca2+. Right, normalized G-V relationships (mean ± SEM) of BK/α+β1 at indicated Ca2+ (n = 7–39). (C) V1/2-Ca2+ relationships (mean ± SEM) for BK/α (open symbols) and BK/α+β1 channels (closed symbols). (D) Q-Ca2+ relationships (mean ± SEM) for BK/α (open symbols) and BK/α+β1 channels (closed symbols).

Mutant and wild-type mouse β1 subunits were subcloned in the mammalian expression vector pIRES2-EGFP (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.), which fluorescently labels cells with channel expression. The mouse α subunit was cotransfected at a ratio of 1:10 α to β1 to ensure saturation of BK channels with β1 subunits.

Macropatch recordings were made using the excised inside-out patch clamp configuration. To limit series resistance errors, currents 5 nA or less were used for steady-state G-V and analysis of channel kinetics. Experiments were performed at 22°C. Data were sampled at 10–30-μs intervals and low-pass filtered at 8.4 kHz using the HEKA EPC8 four-pole bessel filter. Data were analyzed without further filtering. Leak currents were subtracted after the test pulse using P/5 negative pulses from a holding potential of −120 mV. For BK/α+β1, leak subtraction was not performed at 18.5 and 100 μM Ca2+. Patch pipettes (borosilicate glass VWR micropipettes) were coated with Sticky Wax (Kerr Corp.) and fire polished to ∼1.5–3 MΩ resistance.

The external recording solution (electrode solution) was composed of 20 mM HEPES, 140 mM KMeSO3, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2. Internal solutions were composed of a pH 7.2 solution of 20 mM HEPES, 140 mM KMeSO3, 2 mM KCl, and buffered with 5 mM HEDTA and CaCl2 to the appropriate concentrations to give 1.7, 7, and 18.5 μM buffered Ca2+ solutions. Higher Ca2+ solutions were buffered with 5 mM NTA. Low Ca2+ solutions (0.3 μM and 0 Ca2+) were buffered with 5 mM EGTA, and Ba2+ was chelated with 40 μM (+)-18-crown-6-tetracarboxylic acid (Cox et al., 1997b). Free [Ca2+] of buffered solutions were measured using an Orion calcium-sensitive electrode (Orion Research, Inc.).

Analysis of Macroscopic Currents

Conductance–voltage (G-V) relationships were obtained using a test pulse to positive potentials followed by a step to a negative voltage (−80 at low Ca2+, −120 at high Ca2+), and then measuring instantaneous tail current 200 μs after the test pulse. In experiments where Gmax were not reached, including BK/α+β1 and BK/α+β1ΔN11 at 0.005 and 0.3 μM [Ca2+], BK/α+β1ΔC11 and BK/α+β1ΔN10ΔC11 at 0.005 μM [Ca2+], Gmax values at higher [Ca2+] from the same patch were used. G/Gmax-V data were fitted with the Boltzmann function: G = Gmax{1/[1 + e−(V − V1/2)ZF/RT]}, where V is the test potential, V1/2 is the membrane potential at half-maximal conductance, z is the effective gating charge, and F, R, and T are constants.

Single Channel Analysis

Single channel opening events were obtained from patches containing one to hundreds of channels. Recordings are of 20 s to hundreds of seconds duration. Analysis was performed using TAC and TACFIT programs (Bruxton Corporations). NPO was determined using either all-point amplitude histogram or by event detection using a 50% amplitude criteria. The probability (Pk) of occupying each open level (k) give rise to NPO:

|

PO was then determined by normalizing NPO values by channel number (N). N was obtained from the instantaneous tail current amplitude during maximal opening at saturating [Ca2+], divided by the unitary conductance for each channel at the tail voltage. Combined single channel and macroscopic steady-state data in 0 Ca2+ in the presence of F315Y mutation were fit with the dual allosteric model assuming voltage-dependent transitions only (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). Details for fitting parameters are included in figure legends.

RESULTS

Effects of mβ1 on BK Channel Steady-State G-V Relationships

Fig. 1 demonstrates effects of mβ1 on BK channel steady-state gating between 0 and 100 μM Ca2+. BK channels composed of α subunit alone (BK/α) or α with saturating mβ1 expression (BK/α+β1) were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, and macroscopic BK currents were recorded in the inside-out patch clamp configuration. BK currents were evoked by step depolarization at controlled intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 1, A and B, left panels) to obtain normalized steady-state tail conductance versus voltage (G-V) relationships (Fig. 1, A and B, right panels). Averaged V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relationships obtained from Boltzmann fits of the G-V relationship (Fig. 1, C and D) show that mβ1 subunit alters V1/2 and Q in a Ca2+-dependent fashion. In the presence of mβ1, there is a steeper V1/2-Ca2+ relationship (Fig. 1 C) that indicates an increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. Below 1.7 μM Ca2+, mβ1 subunit shifts the G-V relationships to positive potentials. This is most dramatic at nominal 0 Ca2+, where G/Gmax for BK/α+β1 channels only reaches ∼0.23 at 300 mV. Extrapolation of the V1/2 from the Boltzmann fit predicts that mβ1 confers an ∼150-mV positive shift in V1/2. Above 1.7 μM Ca2+, however, mβ1 causes a negative shift in the V1/2 (−50 mV shift at 100 μM Ca2+). In addition, the mβ1 subunit reduces the apparent equivalent gating charge (Q) at low Ca2+ (Fig. 1 D).

Understanding Effects of mβ1 on Channel Gating Energetics in the Context of the HA Gating Model

What are the mechanisms underlying mβ1 modulation of BK channel gating? The current view of BK channel gating is described by a dual allosteric (HA) model (Rothberg and Magleby, 1999; Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002). In this model, channel opening is governed by three equilibrium constants, L (closed-to-open transition), J (voltage sensor activation), K (Ca2+ binding), and D, C, and E, the allosteric couplings between L and J, L and K, and J and K, respectively. Open probability is described by Eq. 1, referring to the HA model (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002):

|

(1) |

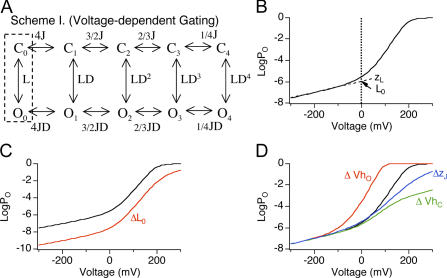

In the absence of Ca2+, the occupied states are reduced to 10 (Fig. 2 A, left),

|

(2) |

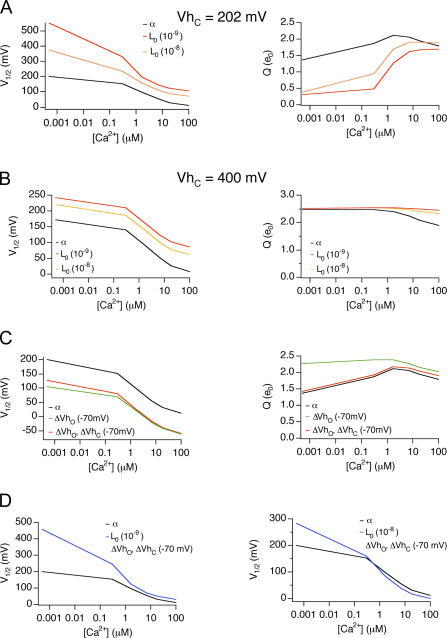

Figure 2.

Effects on 0 Ca2+ logPO-V relation by changes in L0, VhO, VhC, and zJ. (A) BK channel gating scheme at 0 Ca2+ according to the HA model. Channel resides in either open (O) or closed (C) conformation, with zero to four (subscripts) activated (A) voltage sensors. L is the C-O equilibrium constant with all four voltage sensors in the resting (R) state (dashed box). J is the R-A equilibrium constant when channels are closed. D is the allosteric interaction factor between C-O transition and voltage sensor activation. Equilibrium between C-O transitions is allosterically regulated by the states of four independent and identical voltage sensors. (B) Simulated 0 Ca2+ logPO-V relation according to the HA model (L0 = 1 e−6, zL = 0.30 e0, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +200 mV, VhO = +50 mV). Dashed line represents linear fit of the logPO-V relation at the limiting slope. L0 (point where dashed line and zero line cross) and zL (slope of dashed line) are the zero voltage value of L and its partial charge, respectively. (C) Effects on logPO-V relation of changing L0 from 1 e−6 (black) to 1 e−8 (red). Notice the shift of the limiting slope along the Y axis. (D) Effects on logPO-V relation of changing VhO (−50 mV, red), VhC (+100 mV, green), or zJ (0.4 e0, blue) and leaving other parameters the same as in B (black). Notice reducing VhO, but not VhC or zJ shifts the steep phase of the logPO-V relation to more hyperpolarized potentials.

In the absence of Ca2+ and at extremely negative membrane potentials (limiting slope), virtually all voltage sensors reside in the resting state and the occupied states are further reduced to 2 (C0 and O0) (Fig. 2 A, dashed box). Because J is small (J ≪ 1/D), Eq. 2 reduces to

|

(3) |

When PO is small (PO ≪ 0.01), L ≪ 1,

|

(4) |

In this equation, zL is the voltage dependence of the closed-to-open transition and L0 is channel's closed-to-open equilibrium in the absence of Ca2+ and voltage sensor activation at 0 mV (Fig. 2 B). Therefore a direct approach to evaluate effects of β1 on channel's intrinsic closed to open equilibrium is to compare logPO-V at 0 Ca2+ and limiting slope. As predicted by Eq. 4, the position of the limiting slope of logPO along the Y axis is determined entirely by L and zL (Fig. 2 C).

Another advantage of PO measurement near the limiting slope is that it allows one to infer effects on open-channel voltage sensor activation (VhO, see Table I for definitions). As shown in Fig. 2 D, the HA model predicts that membrane potentials where PO transitions from weakly voltage dependent to “steep” voltage dependence is critically dependent on VhO and relatively unaffected by other voltage-dependent parameters, including closed channel voltage sensor activation (VhC) or the charge associated with voltage sensor activation (zJ).

TABLE I.

Definitions of Gating Parameters (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002)

| L | C-O equilibrium constant (unliganded channel, resting voltage sensors). |

| L = L0exp(zLV/kT) | |

| L0 and zL are the zero voltage value of L and its partial charge, respectively. |

|

| J | R-A equilibrium constant (closed, unliganded channel) |

| J = J0 exp(−zJV/kT) | |

| J0 and zJ are the zero voltage value of J and its partial charge, respectively. |

|

| D | Allosteric factor describing interaction between channel opening and voltage sensor activation |

| D = exp [−zJ(VhO − VhC)/kT] | |

| VhC and VhO are half-activating voltage of QC and QO, respectively. | |

| QC and QO are steady-state gating charge distribution for closed or open channels. |

mβ1 Increases Channel's Intrinsic Energetic Barrier for Opening and Shifts Voltage Sensor Activation to Negative Membrane Potentials

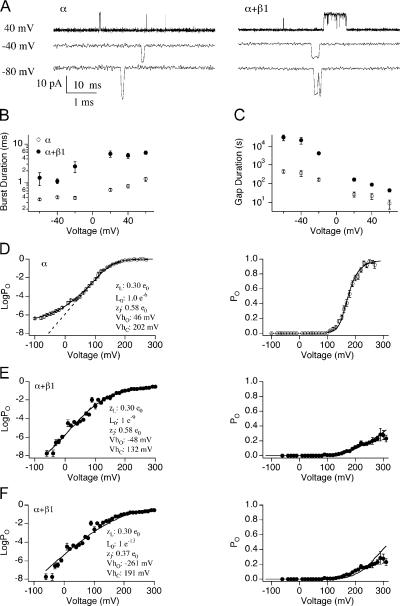

To determine effects of mβ1 on intrinsic and voltage dependent gating, 0 Ca2+ PO was measured over a wide range of voltages in the presence and absence of mβ1. Examples of single channel recordings are displayed in Fig. 3 A. Previously, others have measured bovine β1 effects on dwell time and PO at positive voltages (0 Ca2+ and +30 mV) and found that bovine β1 increased both burst duration (∼20-fold) and gap duration (2–3-fold) for a net sevenfold increase in PO (Nimigean and Magleby, 2000). At a similar voltage (+40 mV), we also found that mβ1 increases both mean burst duration (sixfold) and mean gap duration (fourfold) (Fig. 3, B and C). This resulted in a PO that is similar for α/mβ1 vs. α channels (6.3 e−5 ± 2 e−5 α/mβ1 vs. 6.3 e−5 ± 0.8 e−5 α; Fig. 3, D and E). However, at negative voltages, although the fold change in mean burst duration is somewhat reduced (3.6-fold at −60 mV), mβ1 causes much longer gaps between open events (3 e4 ± 0.9 e4 s BK/α+β1 vs. 4.4 e2 ± 9 e1 s BK/α, −60 mV; see Fig. 3 C). The larger increase in gap duration (∼70-fold) at negative voltages likely underlies a 15-fold reduction in PO of BK/α+β1 channels over BK/α channels (7.4 e−8 ± 5 e−8 vs. 1.1 e−6 ± 2.7 e−7, respectively).

Figure 3.

Evaluating effects of mβ1 on L0 and VhO in the presence of wild type α. (A) Representative single channel currents of BK/α (left) and BK/α+β1 (right) in 0 Ca2+. Time scales are 10 ms for +40 mV and 1 ms for −40 and −80 mV, respectively. (B) Burst duration (mean ± SEM) versus voltage for BK/α (n = 5–10) and for BK/α+β1 (n = 3–13). (C) Gap duration (mean ± SEM) versus voltage for BK/α (n = 5–10) and for BK/α+β1 (n = 3–13). (D) LogPO-V (mean ± SEM, left) and PO-V relations (mean ± SEM, right panel) of BK/α. PO between −120 and +100 mV were measured using single channel recordings (n = 2–13). PO between +110 and +290 mV were measured using macroscopic recordings (n = 12). Linear fit of logPO–V relation at the “steep phase” (dashed line, left) indicates that the measurement either has reached or is approaching the limiting slope. The solid line represents best fits to the HA model (held zL = 0.3 e0, zJ = 0.58 e0, fitting yielded L0 = 1 e−6, VhC = +202 mV, and VhO = 46 mV). (E) LogPO-V (mean ± SEM, left) and PO-V relations (mean ± SEM, right) of BK/α+β1. PO between −60 and +80 mV were measured using single channel recordings (n = 4–22). PO between +90 and +310 mV were measured using macroscopic recordings (n = 7). Linear fit of logPO–V relation at the “steep phase” (dashed line, left panel overlaps with the solid line) indicates that the measurement has not reached the limiting slope. Fits to the HA model were not well constrained, reasonable fits were obtained when L0 ranged between 1 e−10 and 1 e−8. The solid line represents one of the fits (held L0 = 1 e−9, zL = 0.3 e0, zJ = 0–0.58 e0, fitting yielded VhC = +132 mV and VhO = −48 mV). (F) Reducing zJ did not improve the fits. Best fits (solid lines) to the HA model (held zJ = 0.37 e0, zL = 0.3 e0, L0 > 1 e−13, yielded L0 = 1e−13, VhC = +192 mV, and VhO = −261 mV).

Comparison of logPO-V curves for BK/α (Fig. 3 D) and BK/α+β1 (Fig. 3 E) indicates that there are two differences between these channels' steady-state properties. First, whereas the logPO-V curve of BK/α displays a clear transition in voltage dependence (approached limiting slope at approximately +40 mV), logPO-V curve of BK/α+β1 does not. Based on the HA model, this result suggests that mβ1 shifts VhO to more hyperpolarized membrane potentials (Fig. 2 D). In addition, logPO at negative voltages for BK/α is substantially greater than BK/α+β1, indicating a decreased closed to open equilibrium (L0) in the presence of mβ1. To quantify mβ1-mediated changes in L0, VhO, and VhC, data in Fig. 3 (D and E) were fitted using Eq. 2, where zL and zJ were held at 0.30 e0 and 0.58 e0, respectively, based on previous estimates (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Bao and Cox, 2005; Wang et al., 2006). For BK/α, estimated L0, VhO, and VhC were 1 e−6, +46 mV, and +202 mV, respectively (Table II). These values are reasonably close to previous estimates (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Bao and Cox, 2005; Wang et al., 2006). For BK/α+β1, because PO drops so dramatically (PO < 10−8), it was not technically feasible to obtain PO at the limiting slope. Therefore, existing data only provides estimates for the upper and lower limits for L0 (between 1 e−10 and 1 e−8) and VhO (between −70 and −20 mV), whereas VhC is estimated to be ∼+130 mV. We also attempted to improve the fitting for BK/α+β1 by setting equivalent gating charge for voltage sensor activation (zJ) to a lower value. Previously, others had found that some β1 effects on BK channels could be explained by reducing zJ to 0.37 e0, (Orio and Latorre, 2005). However, we found that holding zJ to 0.37 e0 produces a poor fit of BK/α+β1 data (Fig. 3 F), which suggests that mβ1 does not lower zJ.

TABLE II.

Gating Parameters

| zL (e0) | L0 | zJ (e0) | VhC (mV) | VhO (mV) | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 0.30 | 1 e−6 | 0.58 | 202 | 46 | 35.2 |

| F315Y | 0.26 | 9 e−2 | 0.58 | 92 | 35 | 3.7 |

| F315Y+β1 | 0.29 | 1.8 e−3 | 0.58 | 72 | −26 | 9.3 |

| F315Y+β1ΔN11 | 0.24 | 5.5 e−3 | 0.58 | 69 | 15 | 3.4 |

| F315Y+β1ΔC11 | 0.24 | 8 e−3 | 0.58 | 103 | 43 | 3.9 |

| F315Y+β1ΔC5 | 0.26 | 2.8 e−3 | 0.58 | 81 | 15 | 4.8 |

| F315Y+β1ΔN10C11 | 0.13 | 1.3 e−2 | 0.58 | 98 | 29 | 4.8 |

Effects of mβ1 on VhC and VhO that are estimated by fitting PO data using the HA model are similar to those of bβ1 obtained by gating current measurements (Bao and Cox, 2005; Fig. 3 E and Table II). In both cases, β1 shifts VhC to hyperpolarized membrane potentials by ∼70 mV. Gating current measurements found that bβ1 shifts VhO by ∼−60 mV (Bao and Cox, 2005) and our fits estimate that mβ1 causes a VhO shift between −20 and −70 mV. Effects of mβ1 on L0, however, differ from that proposed for bβ1. Whereas a >100-fold decrease in L0 was estimated for mβ1, it was proposed that bβ1 slightly increases L0. Because PO measurement also did not reach the limiting slope in the study performed by Bao and Cox (2005), it is not clear whether bβ1 indeed increases L0. Effects of hβ1 on channel gating was also investigated using ionic currents in the context of the HA model (Orio and Latorre, 2005). The authors proposed that hβ1 significantly decreases L0, VhO, and zJ, with little effects on VhC.

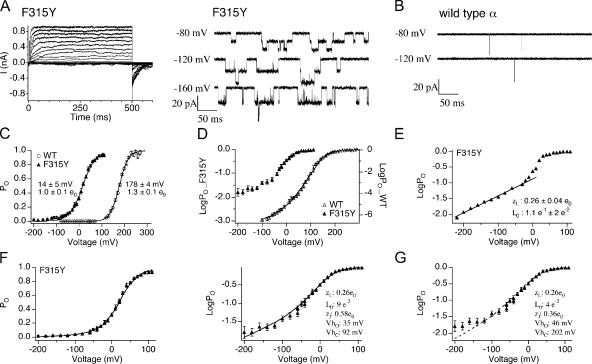

F315Y Mutation Dramatically Increases Channel's Closed-to-Open Transition

The above analysis indicates that mβ1 subunits have effects on BK channels that should be apparent at limiting slope. However, the greatly reduced PO combined with the negative voltage shift of VhO make PO measurements at limiting slope not feasible. Previously it had been shown that F380Y, a point mutation in the S6 transmembrane domain of hslo, significantly increases PO even at 0 Ca2+ (Lippiat et al., 2000). The F380 residue lies in a position within the C-terminal domain of S6 that may serve as the gate for Kv channels (Swartz, 2005). An mslo equivalent of the F380Y mutation was generated (F315Y in mouse) and characterized at 0 Ca2+ using macroscopic and single channel recordings (Fig. 4 A). Similar to previous findings, F315Y shows extremely long open dwell times, (Fig. 4 A, left panel vs. Fig. 4 B). For example, open burst durations are 11 ± 2 ms for F315Y vs. 0.36 ± 0.02 ms for WT α at −60 mV. Similar to previous results, F315Y produces a dramatic leftward shift in the G-V relationship and a decrease in the apparent voltage dependence (Fig. 4 C) (Lippiat et al., 2000). Fitting individual logPO data at limiting slope using Eq. 4 estimated a slight reduction in zL (0.30 wild type α, 0.26 ± 0.04 e0 for F315Y, n = 6). Fitting both logPO and PO data using Eq. 2, gating parameters L0, zJ, VhC, and VhO are estimated to be 9 e−2, 0.58 e0, +92 mV, and +35 mV, respectively (Fig. 4 F and Table II). The large decrease in VhC and little change in VhO decreases D from 35.2 to 3.7, which explains the shallower G-V slope (apparent voltage dependence) for F315Y. To rule out the possibility that the reduced G-V slope can be explained by a reduction in zJ alone, we also fit the F315Y data by holding VhC and VhO at wild-type values, and zL at 0.26 e0 (estimates from limiting slope measurements) (Fig. 4 G). This yielded a poorer fit. In summary, these results indicate that the F315Y has two effects. These are a negative voltage shift of VhC and a greater than 104 increase in L0 relative to wild-type α subunits. We next used the large increase in L0 in F315Y to investigate mechanisms underlying BK channel modulation by the β subunits at limiting slope.

Figure 4.

F315Y mutation greatly increases PO at 0 Ca2+ by increasing L0. (A) Representative macroscopic (left) and single channel (right) recordings of BK/F315Y at 0 Ca2+. (B) Representative single channel currents of BK/α at 0 Ca2+ show opening to be much briefer than the F315Y mutant. (C) G-V relations (mean ± SEM) for BK/α (n = 12) and BK/F315Y (n = 13). F315Y mutation left shifts G-V and decreases the apparent voltage dependence. (D) LogPO-V relations (mean ± SEM) for BK/α (n = 3–12) and BK/F315Y (n = 4–7). (E) Representative logPO-V relations of BK/F315Y where the limiting slope was fitted to Eq. 4 to estimate zL and L0 values (mean ± SEM) are indicated in the figure (n = 6). (F) Best fits to the HA model (held zJ = 0–0.58 e0, zL = 0.26 e0, yielded L0 = 9 e−2, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +92 mV, and VhO = +35 mV). (G) Best fits to the HA model assuming F315Y does not alter VhC and VhO (held zL = 0.26 e0, VhC = +202 mV, and VhO = +46 mV, yielded L0 = 4 e−2, zJ = 0.36 e0).

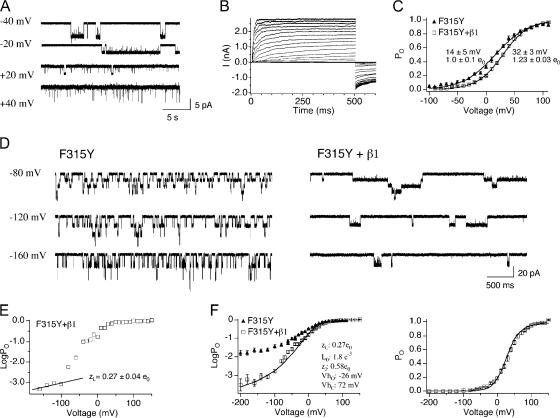

Investigating Effects of β1 on BK Channel Intrinsic and Voltage-dependent Gating Using F315Y

Steady-state gating properties of BK/F315Y+β1 channels were characterized at 0 Ca2+, combining single channel recordings (Fig. 5, A and D, right panels) and macroscopic recordings (Fig. 5 B). Fig. 5 A shows currents from an excised patch containing a single BK/F315Y+β1 channel. Unlike BK/α+β1, BK/F315Y+β1 maximal PO (∼1) (+20 to +40 mV) and maximal conductance at 0 Ca2+ can be easily observed (Fig. 5, B and C). Averaged G-V relationships (Fig. 5 C) suggest that mβ1 shifts the V1/2 to more depolarized membrane potentials, with a slight increase in the slope of the G-V relation. LogPO-V curves of individual patches were fitted using Eq. 4. Similar to wild-type BK channels, mβ1 does not significantly alter zL of F315Y (Fig. 5 E and Table II; BK/F315Y 0.26 ± 0.04 e0, BK/F315Y+β1 0.27 ± 0.04 e0, P = 0.64). We estimated VhC, VhO, and L0 by fitting both PO-V and logPO-V data using Eq. 2. VhC and VhO were estimated to be 72 and −26 mV, respectively (Fig. 5 F and Table II). This is a −20-mV shift of VhC and −61-mV shift of VhO over BK/F315Y channels. Effects on voltage sensor activation estimated by our fits are qualitatively similar to bβ1 measured directly using gating current measurements (Bao and Cox, 2005). However, although shifts of VhO are similar, the −20-mV shift of VhC in the F315Y background is smaller than the −71-mV shift measured by Bao and Cox (2005). Consistent with mβ1 effects on WT α subunit (Fig. 3 E), mβ1 also caused a dramatic (50-fold) reduction of intrinsic gating in the BK/F315Y subunit (Fig. 5 F). L0 for BK/F315Y is 9 e−2 versus 1.8 e−3 for BK/F315Y+β1. In summary, the F315Y mutation allowed us to measure effects on intrinsic gating by mβ1 despite the dramatic reduction in PO. Further, extending PO measurement to the limiting slope provides an assay to measure effects of voltage sensor activation on PO and thereby constrain estimates of VhO using the HA model.

Figure 5.

Evaluating effects of mβ1 on L0 and VhO in the presence of F315Y. (A) An example of single channel recordings of BK/F315Y+β1 at 0 Ca2+. Notice that maximum PO reaches ∼1. (B) Representative macroscopic recordings of BK/F315Y+β1 at 0 Ca2+. (C) G-V relation (mean ± SEM) for BK/F315Y (n = 13) and BK/F315Y+β1 (n = 28). (D) Representative single channel recordings for BK/F315Y and BK/F315Y+β1. Notice that β1 dramatically increases the burst durations. (E) Representative logPO-V relations of BK/F315Y+β1 where the limiting slope were fitted to Eq. 4 to estimate zL, and L0 values indicated in the figure represent mean ± SEM (n = 7). (F) Best fits to the HA model (held zJ = 0.58 e0, zL = 0.27 e0 yielded L0 = 1.8 e−3, VhC = +72 mV, and VhO = −26 mV).

For wild-type α subunits, mβ1 causes a positive G-V shift in low Ca2+ and a negative G-V shift in high Ca2+, with a crossover of the V1/2 around 1.7 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 1 C). This creates a steeper V1/2-Ca2+ relationship. How does β1 modulation of L0 and VhO contribute to these properties? We simulated wild-type α subunit PO (HA model, Eq. 1) across a range of Ca2+ by varying L0, VhO, or both VhO and VhC, either individually or in combination, to understand their effect on the V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relations (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6 A, reducing L0 by mβ1 causes a positive shift of the G-V to a lesser extent at high Ca2+ than at low Ca2+, causing the V1/2-Ca2+ relationship to be more steep. In addition, reducing L0 also reduces Q at low Ca2+. This is because the decrease of L0 causes significant channel openings to occur at much more positive potentials than VhC where voltage-dependent gating rely on the weak voltage dependence of the closed-to-open transition, zL (Wang et al., 2006). Thus, the reduced intrinsic gating creates a double hit to inhibit channel openings: a greater energetic barrier due to L0 and a much weaker voltage dependence (Q) as significant channel openings occur more much positive than VhC (Fig. 6 A, right). Therefore the V1/2 is shifted to far positive values. With the contribution of higher Ca2+ (>1.6 μM), channel openings fall within the range of voltage sensor activation (between VhO and VhC) and the effect of decreased L0 on V1/2 is greatly reduced and fairly uniform across 1.7–100 μM Ca2+. We can see that the HA model predicts that shifting VhC to more positive potentials (Fig. 6 B, e.g., +400 mV) places channel openings within the effective range of voltage sensor activation despite the decrease of L0. In that case, effect of L0 on V1/2 is uniform across both low and high Ca2+ concentrations. Thus, the HA model predicts that mβ1 effects on L0 contribute to a much larger positive shift of the V1/2 and reduced voltage dependence (Q) at low Ca2+ than high calcium, which would steepen the V1/2-[Ca2+] relations.

Figure 6.

Effects on V1/2-Ca2+ relations of changing L0, VhO, or J0. (A) Effects on V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relations by changing L0. PO-V relations were simulated based on the HA model and fitted to the Boltzmann function to obtain V1/2-Ca2+ relations. Gating parameters were the same (zL = 0.30 e0, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +200 mV, VhO = +50 mV, KC = 13 μM, KC = 1.3 μM) except for L0 (L0 = 1 e−6, black line; L0 = 1 e−8, orange line; L0 = 1 e−9, red line). (B) Effects on V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relations by changing L0 when VhC is +400 mV. Gating parameters are same as A except VhC is +400 mV. (C) Effects on V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relations by changing VhO or J0. Gating parameters were the same (zL = 0.30 e0, L0 = 1 e−6, zJ = 0.58 e0, KC = 13 μM, KC = 1.3 μM) except for VhC and VhO, (VhC = +200 mV, VhO = +50 mV, black line; VhC = +200 mV, VhO = −20 mV, solid green line, VhC = +130 mV, VhO = −20 mV, green dash line). (D) Effects on V1/2-Ca2+ relations by changing JO and L0. Black lines (L0 = 1 e−6, VhC = +200 mV, VhO = +50 mV, other parameters as in A); blue line, left (L0 = 1 e−9, VhC = +130 mV, VhO = −20 mV); blue line, right (L0 = 1 e−8, VhC = +130 mV, VhO = −20 mV).

Countering effects on L0, negative shift of VhO alone or both VhO and VhC decreases V1/2 to a similar extent across [Ca2+] (Fig. 6 C). Depending on quantitative changes in L0 combined with VhO, the V1/2-Ca2+ curve may or may not crossover (Fig. 6 D, left and right). In summary, these analyses suggest that mβ1 effects on VhO contribute to the negative G-V shift, and L0 contributes to a steeper V1/2-Ca2+ relationship. However, our analysis does not rule out the possibility that β1 may also have effects on Ca2+ binding or coupling between Ca2+ binding and gating that contribute to changes in Ca2+ sensitivity.

Intracellular Domains of β1 Are Required for β1-mediated Modulation of Voltage-dependent Gating

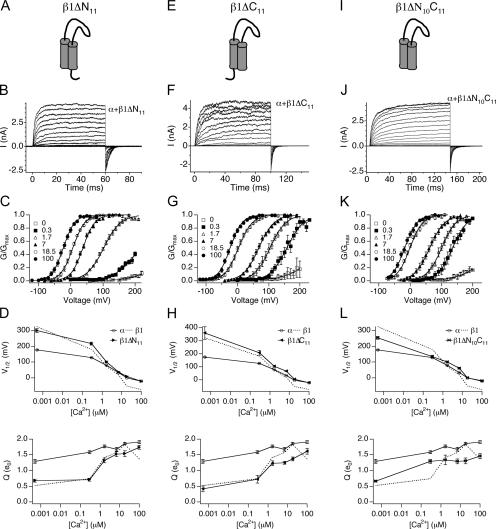

The β1 subunit is composed of a large extracellular domain and small N- (15 amino acids) and C-terminal (12 amino acids) domains. Given that the intracellular domains of the α subunit are required for β1 subunit–mediated G-V shift (Qian et al., 2002), the β1 intracellular domains were deleted to evaluate their role in modulating gating. 11 amino acids that follow the N-terminal initiating methionine and glycine were deleted in β1ΔN11 (Fig. 7 A). In addition, the C-terminal 11 residues were deleted in β1ΔC11 (Fig. 7 E). Effects of β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 on steady-state gating of wild-type α subunit were examined over a wide range of Ca2+ (Fig. 7, B, C, F, and G). These data are summarized in V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ plots (Fig. 7, D and H). Surprisingly, deletion of either intracellular domain has similar effects on the G-V relationship. Both mutants eliminate the negative voltage shift of the G-V relationship in high Ca2+, but maintain the positive G-V shift to varying extents in low Ca2+ (Fig. 7, D and H).

Figure 7.

Intracellular domain deletions of β1 eliminate the leftward shift of the G-V relationship at high Ca2+. (A) Cartoon of the β1ΔN11 mutant. (B) Families of BK/α+β1ΔN11 currents evoked by 60-ms depolarizations in 7 μM Ca2+. (C) Normalized G-V relationships (mean ± SEM) of BK/α+β1ΔN11 at indicated Ca2+ (n = 5–18). (D) V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relationships (mean ± SEM) for BK/α+β1ΔN11 compared with BK/α and BK/α+β1. (E) Cartoon of the β1ΔC11 mutant. (F) Families of BK/α+β1ΔC11 currents evoked by 90-ms depolarizations in 7 μM Ca2+. (G) Normalized G-V relationships (mean ± SEM) of BK/α+β1ΔC11 at indicated Ca2+ (n = 4–26). (H) V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relationships (mean ± SEM) for BK/α+β1ΔC11 compared with BK/α and BK/α+β1. (I) Cartoon of the β1ΔN10ΔC11 mutant. (J) Families of BK/α+β1ΔN10ΔC11 currents evoked by 150-ms depolarizations in 7 μM Ca2+. (K) Normalized G-V relationships (mean ± SEM) of BK/α+β1ΔN10ΔC11 at indicated Ca2+ (n = 3–14). (L) V1/2-Ca2+ and Q-Ca2+ relationships (mean ± SEM) for BK/α+β1ΔN10ΔC11 compared with BK/α and BK/α+β1.

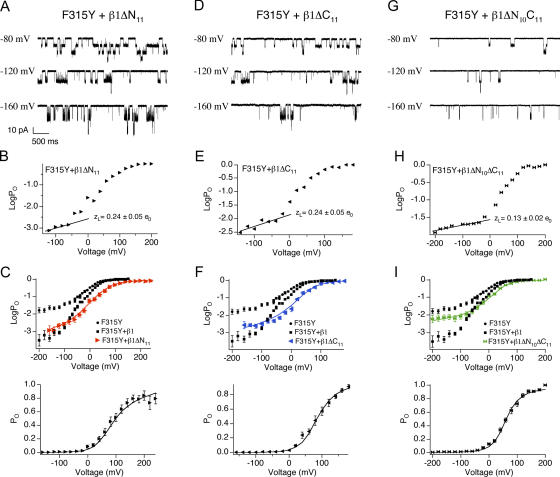

β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 were coexpressed with BK/F315Y to examine whether the mutations affect β1's ability to reduce L0 and VhO. Macroscopic and single channel recordings (Fig. 8) were used to obtain the PO-V relationship. Fitting the logPO-V relationship (Fig. 8, B and E) at limiting slope using Eq. 4 estimated that zL for both β1ΔN11 (0.24 ± 0.05 e0) and β1ΔC11 (0.24 ± 0.05 e0) is not significantly different from wild-type β1 (0.27 ± 0.04 e0, P = 0.46 and P = 0.52 for β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 vs. WT mβ1, respectively). Fitting both PO-V and logPO-V using Eq. 2 (Fig. 8, C and F; Table II), it was found that the major effect of the mβ1 mutations is a reduced leftward shift of VhO. This is from −61-mV shift for wild-type mβ1 to a −20-mV shift for β1ΔN11, and complete elimination in β1ΔC11. β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 reduced L0, compared with α alone (Fig. 8, B and E; 5.5 e−3 and 8 e−3, respectively, relative to 9 e−2 for α), but to a somewhat lesser extent compared with wild-type β1 (1.8 e−3). In summary, these results suggest that the intracellular domains are required for β1 subunit effects on voltage sensor activation and explains why β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 do not negatively shift the G-V relationship (Fig. 7, D and H). In contrast, mutation of the intracellular domains has a much weaker effect on L0.

Figure 8.

Intracellular domain deletions impair β1's ability to reduce L0 and shift VhO. (A) Examples of single channel currents of BK/F315Y+β1ΔN11. (B) Representative logPO-V relations of BK/α+β1ΔN11 where the limiting slope were fitted to Eq. 4 to estimate zL. zL values indicated in the figure represent mean ± SEM (n = 8). (C) Best fits to the HA model (held zL = 0.24 e0, zJ = 0–0.58 e0, yielded L0 = 5.5e−3, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +69 mV, and VhO = +15 mV). (D) Examples of single channel currents of BK/F315Y+β1ΔC11. (E) Representative logPO-V relations of BK/α+β1ΔC11 where the limiting slope was fitted to Eq. 4 to estimate zL. zL value indicated in the figure represents mean ± SEM (n = 5). (F) Best fits to the HA model (held zL = 0.24 e0, zJ = 0–0.58 e0, yielded L0 = 8 e−3, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +103 mV and VhO = +43 mV). (G) Examples of single channel currents of BK/F315Y+β1ΔN10C11. (H) Representative logPO-V relations of BK/F315Y+β1ΔN10C11 where the limiting slope was fitted to Eq. 4 to estimate zL. zL values indicated in the figure represent mean ± SEM (n = 8). (I) Best fits to the HA model (held zL = 0.13 e0, zJ = 0–0.58 e0, yielded L0 = 1.3 e−2, zJ = 0.58 e0, VhC = +98 mV, and VhO = +29 mV).

A caveat to interpreting these results is the possibility that the single deletions are dominant-negative mutants rather than loss of function. It is possible that the intracellular domains of β1 normally do not have a role in stabilizing voltage sensor activation. Deletion of either intracellular domain may expose residues of the other domain for novel interaction with the α subunit that perturbs β1 effects on intrinsic opening and voltage sensor activation. This scenario predicts that deleting both intracellular domains should reconstitute β1 subunit properties. We tested this possibility by generating β1 mutations lacking both N- and C-terminal domains (β1ΔN10ΔC11 and β1ΔN11ΔC11). Coexpression of β1Δ N10ΔC11 with wild-type α demonstrates that the double mutant, like the β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 mutants, eliminates the negative voltage shift of the G-V in high Ca2+ (Fig. 7 L). In addition, the β1ΔN10C11 mutant also perturbs the positive G-V shift in low Ca2+ (Fig. 7 L). These results suggest that the double deletion may also affect β1's ability in modulating L0 and VhO. To directly examine effects of the double deletions on intrinsic and voltage-dependent gating, logPO-V relationship was obtained for BK/F315Y+β1ΔN10C11 using single channel recordings (Fig. 8 G). Fitting logPO-V relationship at limiting slope showed that unlike the single deletions, the β1ΔN10C11 significantly reduces voltage dependence of the closed to open equilibrium (zL is 0.13 ± 0.02 e0; Fig. 8 H). Analysis using Eq. 2 indicates that β1ΔN10C11 dramatically decreases β1's reduction of L0 and eliminates β1's ability to left shift VhO (Fig. 8 I; Table II). The above findings suggest that it is unlikely that β1ΔN11 and β1ΔC11 are dominant-negative mutations, and provides additional evidence that intracellular domains are required for stabilizing voltage sensor activation. Coexpression of wild-type α and β1ΔN11ΔC11 produced currents indistinguishable from BK/α alone (unpublished data). Although the protein was expressed (as assayed by immunohistochemistry; unpublished data), it appears that the conserved E11 residue is critical for coupling between α and β1 when the 10 and 11 residues of the N and the C terminus are deleted.

The β1 subunit has the additional property of reducing the apparent voltage dependence (Q) of the conductance–voltage relationship. Intracellular domain chimeras (BK α chimeras with related slo3 channels) that eliminate the negative shift of the G-V relationship do not affect the apparent voltage dependence (Qian et al., 2002). Similarly, we find that deletion of either intracellular domains and the double deletion, to an extent, still decrease Q (Fig. 7, D, H, and L). In combination with the double deletion effect on the V1/2 at low Ca2+ (Fig. 7 L), these results indicate that some effects by mβ1 are retained by interactions in the transmembrane and/or extracellular domains.

DISCUSSION

Properties of mβ1

Similar to previous analysis of β1 subunits, our results demonstrate that mβ1 reduces the channel's apparent voltage dependence (Q) and increases its apparent Ca2+ sensitivity. The increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity is manifested in two ways; a negative shift of the G-V relationship at micromolar Ca2+, and a steeper V1/2–Ca2+ curve. These effects have been previously observed for human β1 (hβ1) (Meera et al., 1996; Nimigean and Magleby, 1999; Lippiat et al., 2003; Orio and Latorre, 2005) and bovine β1 (bβ1) (Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Bao and Cox, 2005). Several of these studies also observed that below ∼1 μM Ca2+, β1 either becomes less “effective” in shifting G-V relations (Meera et al., 1996; Cox and Aldrich, 2000; Nimigean and Magleby, 2000; Bao and Cox, 2005) or produces a positive shift in the G-V relationship (Orio and Latorre, 2005). Our studies with mβ1 concur with the later, and indeed show a very large positive shift at submicromolar Ca2+.

How do β1 subunits confer an increase in apparent Ca2+ sensitivity, and an increased slope for the V1/2–Ca2+ curve? By combining the F315Y limiting slope analysis with mutagenesis of the intracellular domain, we were able to uncover mechanisms that contribute to these properties. Utilization of the F315Y mutation with β1 allowed us to directly measure the effect on PO by the negative shift of voltage sensor activation, as predicted by previous gating current measurements (Bao and Cox, 2005). The decrease in VhO and the negative shift of the G-V relationship are correlated in our mutations, indicating that effects on voltage sensor equilibrium by β1 may be causal for the negative G-V shift, as predicted by Bao and Cox (2005). However, our simulations indicate that the negative G-V shift occurs equally across Ca2+ concentrations. This indicates that the increased slope of the V1/2–Ca2+ curve is not accounted for by effects on voltage sensor equilibrium. Rather, we found that β1 decrease of intrinsic gating (L0) contributes to the increased slope of the V1/2–Ca2+ curve. Unlike VhO, the effect of L0 on V1/2 appears to be Ca2+ dependent where there is a greater positive shift of the G-V curve at low Ca2+ than high Ca2+. Surprisingly, it is this β1 effect that reduces PO more so at low Ca2+ than at high calcium that gives a steeper Ca2+ response.

Previous studies had also inferred that human β1 decreased BK channel's closed-to-open equilibrium (Orio and Latorre, 2005). However, this is somewhat controversial given that Bao et al. did not require a decreased closed to open equilibrium to explain bovine β1 subunit effects (Bao and Cox, 2005). In part, this discrepancy may also be due to species differences. At 0 Ca2+, V1/2 for oocyte-expressed BK channels composed of mouse α (mslo-mbr5; Butler et al., 1993) and bovine β1 (Knaus et al., 1994) is ∼200 mV (Bao and Cox, 2005), and for BK channels composed of human α and human β1 expressed in oocytes is ∼250 mV (Orio and Latorre, 2005). In our study, mouse α (Pallanck and Ganetzky, 1994) and mouse β1 expressed in HEK293 cells resulted in an estimated V1/2 to be >300 mV. Thus, mouse (this study) and human β1 subunits (Orio and Latorre, 2005) may have a greater effect on L0 than the bovine β1 subunit (Bao and Cox, 2005). An additional variable is the expression system. Functional interaction between BK channel α and β subunits has been shown to be phosphorylation dependent (Erxleben et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2002). It is possible that similar to KCNQ channels (Nakajo and Kubo, 2005), BK channel phosphorylation status differs between oocytes (used in the previous studies) and HEK293 cells (used in this study).

β1 and β4 Subunits Share Similar Mechanisms

Interestingly, the major effects of β4 are similar to the mouse β1 subunit. Both cause a decrease in intrinsic opening and leftward voltage shifts for voltage sensor activation (Wang et al., 2006). The distinction is that the β1 subunit has a crossover between inhibition and activation at low micromolar Ca2+ concentrations and is therefore generally regarded to promote channel activation. The β4 subunit, in contrast, has a crossover at tens of micromolar Ca2+ concentration and is generally regarded to be a down-regulator for BK channels (Weiger et al., 2000; Brenner et al., 2005). It is indeed possible that quantitative differences in these two opposing effects, intrinsic gating or voltage sensor activation, underlie the distinction between β1 and β4 subunits.

β1 Functional Domains

Finally, these studies contribute to our understanding of β1 subunit domains that mediate interaction with BK channels. Previous studies using chimeras between β1 and β2 indicate that differences between these subunits can be ascribed to differences in the intracellular domains of the β subunits (Orio and Latorre, 2005). Consistent with these studies, we find that most, but not all, of the effects of β1 (effects on VhO and L0) are mediated by the intracellular domains. Predominant effects of the extracellular and transmembrane domain appear to be its influence on the equivalent gating charge conferred by β1 subunits, and also a small effect on L0. An intriguing possibility may be that the intracellular domains of the β1 subunit directly interact with the voltage sensor domain to modulate channel activation. Indeed, the recent finding that residues in S2 and S3, in addition to the S4 transmembrane domains, contribute to voltage sensor equilibrium (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Ma et al., 2006) present the possibilities that β1 intracellular domains may be tugging on any of the respective intracellular loops for S2–S4 to mediate effects on VhO.

However, other studies have found that perturbing the α subunit N-terminal extracellular domain and the first transmembrane (S0) domains also has a profound effect on the negative shift of the G-V relationship conferred by β1 (Wallner et al., 1996; Morrow et al., 2006). We cannot rule out the possibility that intracellular domains and transmembrane/extracellular domains of β1 are allosterically coupled so that mutations in either domain perturb β1 subunit effects. Alternatively, mutations in the extracellular domain of α and intracellular domains of β1 affect different aspects of BK channel gating that appear qualitatively similar if measured by the net effect of the G-V relationship. In this regard, future studies using the F315Y limiting slope analysis should provide a more accurate mapping of α and β1 subunit functional domains.

F315Y Provides a Useful Reagent for Measuring BK Channel Properties at the Limiting Slope

Historically, a number of other ion channel mutations have served to uncover mechanisms that would otherwise be difficult or not possible to resolve. One example is the ILT Shaker mutation. By separating the final open transitions from charge movement steps (Smith-Maxwell et al., 1998), the ILT mutation allowed biophysical studies to probe channel gating mechanisms (del Camino et al., 2005; Pathak et al., 2005). As well, the W434F mutation of Shaker channel blocks potassium conductance and facilitates gating current measurements (Perozo et al., 1993). Yet, as useful as these mutations are, they have their own caveats with regard to how they affect other channel gating properties. For example, W434F, in addition to blocking channel conductance, it also retains channels in a c-type inactivated state (Yang et al., 1997). This begs the question of how the F315Y mutation affects our ability to infer β1 modulation of gating.

The F315Y mutation is located in the C-terminal residues of the S6 domain, a region that is ascribed to serving as the gate for Kv channels (Swartz, 2005). Our observations were that the F315Y had two effects. Most dramatic was an increase in intrinsic gating that is apparent as a large (30-fold) increase in open channel dwell times (Fig. 4; 11 ± 2 ms F315Y vs. 0.36 ± 0.02 ms WT α at −60 mV, 5 nM Ca2+) and ∼10,000-fold increase in limiting slope PO (Fig. 4 D). As well, fitting to the HA model indicates a negative shift of voltage sensor activation of closed channels (VhC, Table II), perhaps indicating a change in channel conformation in the closed state. Taken together, a simplistic hypothesis is that the F315Y mutation destabilizes the closed gate. Thus, although F315Y may not be useful in reporting effects on VhC, several lines of evidence suggest that other F315Y and β1 properties are qualitatively additive, indicating that their mechanisms are independent and not masked. Compared with wild-type BK/α channels, BK/α+β1 and BK/F315Y both display increased mean burst duration (Fig. 3 B; Nimigean and Magleby, 1999). Despite the dramatically increased burst durations of F315Y, this property of β1 is conserved in the F315Y background (Fig. 5 D; F315Y+β1 is 334 ± 12 ms vs. 11 ± 2 ms F315Y alone at −60 mV, 5 nM Ca2+). In addition, β1 subunits confer a reduction in L0 in the F315Y background despite the large increase in intrinsic gating (L0) by the α mutation. Other properties of β1 also appear to be qualitatively retained, including the negative shift of open channel voltage sensor activation previously reported by Bao and Cox (2005). Thus, in many aspects, F315Y has effectively uncovered β1-mediated modulation of BK channels.

With regard to estimating VhC, it is not clear if the F315Y mutation reports β1 effects. Bao and Cox saw that bβ1 conferred similar shifts of both VhO (−61 mV) and VhC (−71 mV). Our estimates of mβ1 were an unequal shift of VhO (−61 mV) and VhC (−20 mV) in the F315Y background. The fact that F315Y alone has a VhC (+110 mV, Table II) that is quite different than wild-type α subunits (+202 mV) creates the possibility that the F315Y mutation perturbs β1 effects on VhC.

In conclusion, the increase in PO by the F315Y mutation has uncovered properties that were predicted by gating current measurements, and novel properties such as effects on intrinsic gating that were previously difficult to measure. One can predict that the mutation should continue to provide a valuable tool to identify critical residues that bridge functional interactions between the BK channel α and β1 subunits.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Richard Aldrich, Frank Horrigan, Brad Rothberg, and David Weiss for advice and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a National American Heart Association grant 0335007N and Sandler Program For Asthma Research to R. Brenner. B. Wang is supported by National Institutes of Health T32 training grant HL04776-23.

Olaf S. Andersen served as editor.

Abbreviation used in this paper: BK, large-conductance Ca2+- and voltage-activated K+.

References

- Bao, L., and D.H. Cox. 2005. Gating and ionic currents reveal how the BKCa channel's Ca2+ sensitivity is enhanced by its β1 subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:393–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, R., T.J. Jegla, A. Wickenden, Y. Liu, and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. a. Cloning and functional characterization of novel large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel β subunits, hKCNMB3 and hKCNMB4. J. Biol. Chem. 275:6453–6461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, R., G.J. Perez, A.D. Bonev, D.M. Eckman, J.C. Kosek, S.W. Wiler, A.J. Patterson, M.T. Nelson, and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. b. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 407:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, R., Q.H. Chen, A. Vilaythong, G.M. Toney, J.L. Noebels, and R.W. Aldrich. 2005. BK channel β4 subunit reduces dentate gyrus excitability and protects against temporal lobe seizures. Nat. Neurosci. 8:1752–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A., S. Tsunoda, D.P. McCobb, A. Wei, and L. Salkoff. 1993. mSlo, a complex mouse gene encoding “maxi” calcium-activated potassium channels. Science. 261:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderone, V. 2002. Large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels: function, pharmacology and drugs. Curr. Med. Chem. 9:1385–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.H., J. Cui, and R.W. Aldrich. 1997. Separation of gating properties from permeation and block in mslo large conductance Ca-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 109:633–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.H., and R.W. Aldrich. 2000. Role of the β1 subunit in large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel gating energetics.Mechanisms of enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:411–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Camino, D., M. Kanevsky, and G. Yellen. 2005. Status of the intracellular gate in the activated-not-open state of shaker K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworetzky, S.I., C.G. Boissard, J.T. Lum-Ragan, M.C. McKay, D.J. Post-Munson, J.T. Trojnacki, C.P. Chang, and V.K. Gribkoff. 1996. Phenotypic alteration of a human BK (hSlo) channel by hSloβ subunit coexpression: changes in blocker sensitivity, activation/relaxation and inactivation kinetics, and protein kinase A modulation. J. Neurosci. 16:4543–4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erxleben, C., A.L. Everhart, C. Romeo, H. Florance, M.B. Bauer, D.A. Alcorta, S. Rossie, M.J. Shipston, and D.L. Armstrong. 2002. Interacting effects of N-terminal variation and strex-exon splicing on slo potassium channel regulation by calcium, phosphorylation and oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27045–27052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff, V.K., J.E. Starrett Jr., and S.I. Dworetzky. 1997. The pharmacology and molecular biology of large-conductance calcium-activated (BK) potassium channels. Adv. Pharmacol. 37:319–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan, F.T., and R.W. Aldrich. 2002. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:267–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, P., T.M. Weiger, Y. Wu, and I.B. Levitan. 2002. Phosphorylation-dependent functional coupling of hSlo calcium-dependent potassium channel and its hβ4 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10014–10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski, G.J., H.G. Knaus, R.J. Leonard, O.B. McManus, and M.L. Garcia. 1996. High-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; structure, pharmacology, and function. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28:255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus, H.G., M. Garcia-Calvo, G.J. Kaczorowski, and M.L. Garcia. 1994. Subunit composition of the high conductance calcium-activated potassium channel from smooth muscle, a representative of the mSlo and slowpoke family of potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3921–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippiat, J.D., N.B. Standen, and N.W. Davies. 2000. A residue in the intracellular vestibule of the pore is critical for gating and permeation in Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels. J. Physiol. 529 (Pt. 1):131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippiat, J.D., N.B. Standen, I.D. Harrow, S.C. Phillips, and N.W. Davies. 2003. Properties of BK(Ca) channels formed by bicistronic expression of hSloα and β1-4 subunits in HEK293 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 192:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z., X.J. Lou, and F.T. Horrigan. 2006. Role of charged residues in the S1-S4 voltage sensor of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:309–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus, O.B., L.M. Helms, L. Pallanck, B. Ganetzky, R. Swanson, and R.J. Leonard. 1995. Functional role of the β subunit of high conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Neuron. 14:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meera, P., M. Wallner, Z. Jiang, and L. Toro. 1996. A calcium switch for the functional coupling between α (hslo) and β subunits (KV,Ca β) of maxi K channels. FEBS Lett. 382:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, J.P., S.I. Zakharov, G. Liu, L. Yang, A.J. Sok, and S.O. Marx. 2006. Defining the BK channel domains required for β1-subunit modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:5096–5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajo, K., and Y. Kubo. 2005. Protein kinase C shifts the voltage dependence of KCNQ/M channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 569:59–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimigean, C.M., and K.L. Magleby. 1999. The β subunit increases the Ca2+ sensitivity of large conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels by retaining the gating in the bursting states. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimigean, C.M., and K.L. Magleby. 2000. Functional coupling of the β1 subunit to the large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in the absence of Ca2+. Increased Ca2+ sensitivity from a Ca2+-independent mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 115:719–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio, P., and R. Latorre. 2005. Differential effects of β1 and β2 subunits on BK channel activity. J. Gen. Physiol. 125:395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallanck, L., and B. Ganetzky. 1994. Cloning and characterization of human and mouse homologs of the Drosophila calcium-activated potassium channel gene, slowpoke. Hum. Mol. Genet. 3:1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, M., L. Kurtz, F. Tombola, and E. Isacoff. 2005. The cooperative voltage sensor motion that gates a potassium channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 125:57–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo, E., R. MacKinnon, F. Bezanilla, and E. Stefani. 1993. Gating currents from a nonconducting mutant reveal open-closed conformations in Shaker K+ channels. Neuron. 11:353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluger, S., J. Faulhaber, M. Furstenau, M. Lohn, R. Waldschutz, M. Gollasch, H. Haller, F.C. Luft, H. Ehmke, and O. Pongs. 2000. Mice with disrupted BK channel β1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca2+ spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ. Res. 87:E53–E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X., C.M. Nimigean, X. Niu, B.L. Moss, and K.L. Magleby. 2002. Slo1 tail domains, but not the Ca2+ bowl, are required for the β1 subunit to increase the apparent Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 120:829–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, B.S., and K.L. Magleby. 1999. Gating kinetics of single large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in high Ca2+ suggest a two-tiered allosteric gating mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:93–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Maxwell, C.J., J.L. Ledwell, and R.W. Aldrich. 1998. Uncharged S4 residues and cooperativity in voltage-dependent potassium channel activation. J. Gen. Physiol. 111:421–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, K.J. 2005. Structure and anticipatory movements of the S6 gate in Kv channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 126:413–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y., P. Meera, M. Song, H.G. Knaus, and L. Toro. 1997. Molecular constituents of maxi KCa channels in human coronary smooth muscle: predominant α + β subunit complexes. J. Physiol. 502:545–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner, M., P. Meera, and L. Toro. 1996. Determinant for b-subunit regulation in high-conductance voltage-activated and Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels: an additional transmembrane region at the N terminus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:14922–14927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., B.S. Rothberg, and R. Brenner. 2006. Mechanism of β4 subunit modulation of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:449–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiger, T.M., M.H. Holmqvist, I.B. Levitan, F.T. Clark, S. Sprague, W.J. Huang, P. Ge, C. Wang, D. Lawson, M.E. Jurman, et al. 2000. A novel nervous system β subunit that downregulates human large conductance calcium-dependent potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 20:3563–3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Y. Yan, and F.J. Sigworth. 1997. How does the W434F mutation block current in Shaker potassium channels? J. Gen. Physiol. 109:779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]