Abstract

Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1β (HNF-1β) is a Pit-1, Oct-1/2, Unc-86 (POU) homeodomain-containing transcription factor expressed in the kidney, liver, pancreas, and other epithelial organs. Mutations of HNF-1β cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young, type 5 (MODY5), which is characterized by early-onset diabetes mellitus and congenital malformations of the kidney, pancreas, and genital tract. Knockout of HNF-1β in the mouse kidney results in cyst formation. However, the signaling pathways and transcriptional programs controlled by HNF-1β are poorly understood. Using genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation and DNA microarray (ChIP-chip) and microarray analysis of mRNA expression, we identified SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling-3) as a previously unrecognized target gene of HNF-1β in the kidney. HNF-1β binds to the SOCS3 promoter and represses SOCS3 transcription. The expression of SOCS3 is increased in HNF-1β knockout mice and in renal epithelial cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. Increased levels of SOCS-3 inhibit HGF-induced tubulogenesis by decreasing phosphorylation of Erk and STAT-3. Conversely, knockdown of SOCS-3 in renal epithelial cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β rescues the defect in HGF-induced tubulogenesis by restoring phosphorylation of Erk and STAT-3. Thus, HNF-1β regulates tubulogenesis by controlling the levels of SOCS-3 expression. Manipulating the levels of SOCS-3 may be a useful therapeutic approach for human diseases induced by HNF-1β mutations.

Keywords: chromatin, kidney, transcription, tubulogenesis, TCF2

Although first identified as a liver-specific transcription factor, hepatocyte nuclear factor-1β (HNF-1β) is also highly expressed in other epithelial organs, including the kidney and pancreas (1). In the kidney, HNF-1β is restricted to epithelial cells composing the renal tubules and collecting ducts (2). Mutations or large deletions of the gene encoding HNF-1β (TCF2) produce the autosomal dominant disorder maturity-onset diabetes of the young, type 5 (MODY5) (3, 4). This syndrome has also been named renal cysts and diabetes (RCAD), because affected individuals present with severe cystic kidney disease that often leads to kidney failure. The renal manifestations include simple cysts, multicystic renal dysplasia, and hypoplastic glomerulocystic disease (4, 5). Inactivation of HNF-1β in the mouse kidney, either by kidney-specific gene knockout or transgenic expression of dominant-negative mutants, results in renal cyst formation (6–8). Analysis of mutant mice has revealed that HNF-1β is a major regulator of cystic disease genes, such as PKHD1, PKD2, and UMOD (6, 7). In addition, mutations of HNF-1β induce defects in planar cell polarity, which has also been implicated in polycystic kidney disease (9). Although several target genes have been found, they do not fully define the transcriptional regulatory circuitry responsible for the physiological and pathological functions of HNF-1β.

In addition to causing inherited RCAD/MODY5, mutations of HNF-1β are increasingly recognized as a cause of isolated congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) (10). CAKUT is common in the general population and manifests as structural abnormalities of the kidney, including renal hypoplasia, dysplasia, agenesis, and horseshoe kidney. Mutations of HNF-1β have recently been identified in children with sporadic renal hypoplasia/dysplasia and are a frequent cause of bilateral hyperechogenic kidneys detected by prenatal ultrasonography (11, 12). Studies in Xenopus embryos have shown that HNF-1β plays an important role in the normal development of the kidney (13). In other organs, mutations of HNF-1β are associated with pancreatic hypoplasia, biliary duct defects, and anomalies of the male and female genital tracts (4). Tissue-specific knockout of HNF-1β during mouse embryonic development results in pancreatic agenesis and biliary dysgenesis (14, 15). A common feature of these disorders is a defect in epithelial tubulogenesis. However, little is known about how HNF-1β regulates tubulogenesis and how mutations of HNF-1β disrupt this process.

Results

Identification of HNF-1β Target Genes in the Kidney.

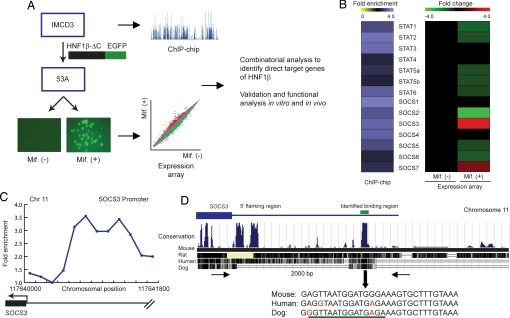

We developed a combinatorial genomic approach to identify potential target genes whose promoters were occupied by HNF-1β in renal epithelial cells and whose expression depended on the function of HNF-1β (Fig. 1A). The first step was to identify HNF-1β target genes in a genome-wide manner using ChIP-chip analysis. Chromatin was isolated from mIMCD3 cells, a cell line derived from the mouse inner medullary collecting duct, and immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antibody against HNF-1β. The immunoprecipitated DNA was fluorescently labeled and hybridized to DNA microarrays containing mouse promoter sequences. The DNA tiling microarrays contained 50-mer oligonucleotides covering 1.5 kb of the promoter regions of 26,842 annotated mouse genes. The genomic loci occupied by HNF-1β were identified as peaks of fluorescence intensity produced by hybridization of ChIP-enriched DNA fragments to the target gene promoter (16) (Fig. 1A). Next, to identify genes whose expression was controlled by HNF-1β, we generated a cell line (53A) by stably transfecting mIMCD3 cells with an inducible expression plasmid that encodes mutant HNF-1β (HNF-1β ΔC) in the presence of mifepristone. The HNF-1β ΔC mutant lacks the C-terminal transcriptional activation domain but retains DNA-binding and dimerization capacity, thus conferring a dominant-negative effect on HNF-1β-mediated gene transcription (8). By comparing gene expression in the absence or presence of dominant-negative HNF-1β, we identified genes whose transcription was directly or indirectly regulated by HNF-1β (Fig. 1A). Combining the results of the ChIP-chip assay and the expression microarray assay enabled us to identify direct target genes of HNF-1β.

Fig. 1.

Identification of SOCS3 as an HNF-1β target gene by combinatorial genomics analysis. (A) Strategy to identify direct HNF-1β target genes by ChIP-chip and expression microarrays. Plot (blue) shows hybridization of immunoprecipitated DNA to promoters on chromosome 11. Photomicrograph shows GFP-positive cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β (HNF-1β ΔC) after treatment with mifepristone [Mif.(+)]. Scatter plot shows increased (red) or decreased (green) gene expression. (B) ChIP-chip enrichment of genes in the STAT and SOCS families (Left). Expression microarrays (Right) identified reciprocal changes in SOCS3 and SOCS2 mRNA levels after expression of HNF-1β ΔC. (C) ChIP-chip enrichment of sequences bound to HNF-1β along the 1.5-kb mouse SOCS3 promoter. The HNF-1β-binding region was identified by peak fitting. (D) The promoter sequence containing the consensus HNF-1β-binding site (underlined) was highly conserved among different mammalian species.

Identification of Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling-3 (SOCS3) as an HNF-1β Target Gene.

Among the target genes identified with this combinatorial genomic approach, SOCS3 and suppressor of cytokine signaling-2 (SOCS2), two genes in the JAK-STAT-SOCS families, showed dramatic changes in expression in response to the HNF-1β ΔC mutant (Fig. 1B). The expression of SOCS3 was increased, whereas the levels of SOCS2 were decreased in the presence of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. ChIP-chip analysis indicated that both SOCS3 and SOCS2 were direct targets of HNF-1β (Fig. 1B). Further analysis of the ChIP-chip data indicated that the SOCS3 promoter was bound by HNF-1β, as indicated by enrichment of hybridization signals along 1.5 kb of the SOCS3 promoter on mouse chromosome 11 (Fig. 1C). The location of peak enrichment allowed the binding region to be narrowed down to ≈250 bp. The 250-bp region contained a consensus binding site for HNF-1β that was highly conserved among different mammalian species, suggesting that regulation of SOCS3 gene expression by HNF-1β may be a common molecular mechanism in mammals (Fig. 1D).

SOCS-3 is a member of the SOCS family that plays crucial roles in negatively regulating the response of cells to growth factors and cytokines. SOCS-3 inhibits JAK/STAT signaling by decreasing the phosphorylation of JAK2 and blocking the activation of downstream STATs. Through this mechanism, SOCS-3 prevents sustained activation of cellular signaling machinery and allows fine-tuning of the intensity and duration of signal transduction (17, 18). In addition to inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway, SOCS-3 also has been shown to inhibit Erk activation and FAK signaling, although the mechanism of the latter is not clear (19, 20).

Mutations of HNF-1β Increase SOCS3 Expression.

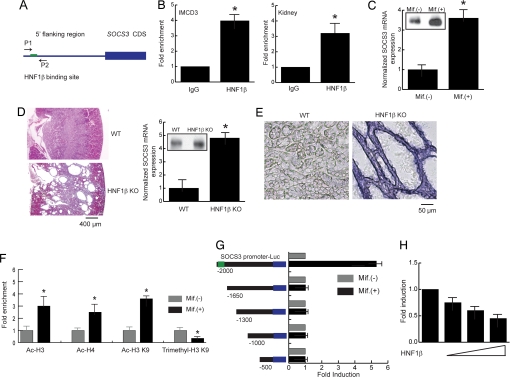

To verify that the SOCS3 promoter is bound by HNF-1β in vivo, we performed directed ChIP assays using primers flanking the HNF-1β-binding site (Fig. 2A). The immunoprecipitated genomic fragment bound by HNF-1β was quantified, and the results indicated that endogenous HNF-1β associated with the SOCS3 promoter in both mIMCD3 cells and kidney tissues (Fig. 2B). To verify the dependence of SOCS3 expression on HNF-1β, the mRNA levels of SOCS3 were measured in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. Expression levels of SOCS3 increased 4-fold after induction of HNF-1β ΔC (Fig. 2C). In agreement with this finding, the levels of SOCS-3 protein were also increased in the presence of dominant-negative HNF-1β. We further investigated the effects of inactivation of HNF-1β on the expression of SOCS3 in the kidney using knockout mice. As shown (6), kidney-specific knockout of HNF-1β resulted in polycystic kidney disease. In mutant mice, the renal medulla was almost completely replaced by multiple large cysts (Fig. 2D). The levels of SOCS3 mRNA in the kidneys of HNF-1β knockout mice were increased 5-fold compared with wide-type controls (Fig. 2D). Immunoprecipitation with anti-SOCS3 antibody indicated that SOCS-3 protein levels were also increased in the kidneys from HNF-1β knockout mice. In situ hybridization analysis showed that SOCS3 mRNA was weakly expressed in wild-type renal tubules and was up-regulated in the cyst epithelial cells in kidney-specific HNF-1β knockout mice (Fig. 2E). Collectively, these results indicate that SOCS3 is a direct target gene that is negatively regulated by HNF-1β, and inactivation of HNF-1β results in increased expression of SOCS3.

Fig. 2.

HNF-1β is a transcriptional repressor of the SOCS3 gene. (A) Schematic diagram of the SOCS3 promoter. Arrows indicate primers flanking the HNF-1β binding site that were used for ChIP. (B) Occupancy of the SOCS3 promoter by HNF-1β was verified by quantitative ChIP in mIMCD3 cells and mouse kidney tissue. (C) Induction of HNF-1β ΔC resulted in increased expression of SOCS3 mRNA. Inset shows increased SOCS-3 protein levels measured by immunoprecipitation. (D) Kidney-specific knockout of HNF-1β generated a cystic phenotype. SOCS3 mRNA expression was increased in kidneys from knockout mice compared with wild-type controls. Inset shows SOCS-3 protein levels measured by immunoprecipitation of kidney tissues from wild type and knockout mice. (E) In situ hybridization showed that SOCS3 mRNA was weakly expressed in wild-type renal tubules (Left) and was up-regulated in the renal cysts of mice with kidney-specific knockout of HNF-1β (Right). (F) Induction of HNF-1β ΔC enhanced acetylation of histone H3 and H4 on the SOCS3 promoter. Acetylation of H3 K9 was increased after expression of HNF-1β ΔC, whereas trimethylation was inhibited. (G) Serial deletion analysis indicated that the region containing the HNF-1β binding site was indispensable for HNF-1β- dependent inhibition of SOCS3 promoter activity. (H) Transfection of exogenous wild-type HNF-1β decreased SOCS3 promoter activity in HeLa cells that lack endogenous HNF-1β. Error bars indicate SD. * indicates P < 0.05.

HNF-1β Is a Transcriptional Repressor of the SOCS3 Gene.

To further analyze the transcriptional regulation of the SOCS3 gene by HNF-1β, we investigated changes in histone modification on the SOCS3 promoter in the presence or absence of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. Covalent histone modifications were measured by quantitative ChIP assays using antibodies that specifically recognize acetylation and methylation of histone residues. Enhanced acetylation of histone H3, histone H4, and lysine-9 of histone H3 (H3 K9) was observed after induction of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β, consistent with enhanced transcription of SOCS3 because of loss of function of HNF-1β (Fig. 2F). Concomitantly, trimethylation of H3 K9, a marker of transcriptional repression, was decreased by expression of HNF-1β ΔC, further confirming that SOCS3 was negatively regulated by HNF-1β. Deletion analysis was performed to identify the region of the SOCS3 promoter responsible for HNF-1β-mediated transcriptional suppression. The SOCS3 promoter (2 kb) was fused with a luciferase reporter gene, then transfected into mIMCD3 cells. Serial deletions indicated that the region between −2000 and −1650, which contained the HNF-1β-binding site, was absolutely required for suppression of the SOCS3 promoter by HNF-1β (Fig. 2G). Site-directed mutagenesis of the HNF-1β-binding site on the SOCS3 promoter abolished transcriptional repression by HNF-1β [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]. In addition, introduction of exogenous HNF-1β protein into HeLa cells, which lack endogenous HNF-1β, inhibited SOCS3 promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2H). This result suggested that HNF-1β by itself was sufficient to inhibit the transcription of the SOCS3 gene. Taken together, these results indicate that HNF-1β is a prototypical tissue-specific transcriptional repressor of the SOCS3 gene.

HNF-1β Is Essential for Renal Tubulogenesis.

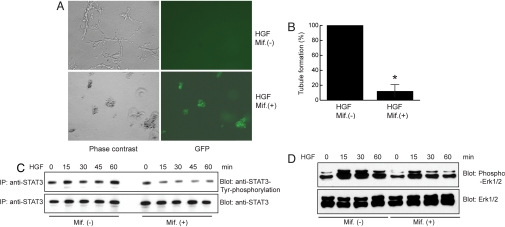

Tubules are the basic units that compose epithelial organs such as the kidney, pancreas, liver, and lung. During embryogenesis, tubule formation is induced by morphogenetic growth factors, including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (21, 22). HGF induces tubulogenesis of epithelial cells through activation of cell signaling molecules such as Erk, FAK, and STAT3 (23–25). Thus, mutations of HNF-1β, by causing overexpression of SOCS-3, could inhibit activation of Erk and STAT3 and impair tubule formation leading to defective kidney development. To investigate this possibility, we assessed the effects of HNF-1β mutations on renal epithelial cell tubulogenesis. As shown (26), mIMCD3 cells formed tubules when grown in 3D collagen gels in the presence of HGF. However, HGF-dependent tubule formation was strongly inhibited in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β (Fig. 3A). Quantification of these data showed that the number of tubules was decreased 85% by the induction of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β (Fig. 3B), indicating that HNF-1β is required for tubulogenesis in renal epithelial cells. Further analysis indicated that expression of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β, which caused overexpression of SOCS-3, resulted in decreased activation of JAK2 (data not shown) and STAT3 and diminished phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β inhibits tubulogenesis by suppressing HGF-induced phosphorylation of Erk and STAT3. (A) Expression of HNF-1β ΔC in mIMCD3 cells abolished HGF-induced tubule formation as shown by phase-contrast microscopy. Expression of HNF-1β ΔC was indicated by GFP-positive cells. (B) Quantification of tubule formation in mIMCD3 cells after expression of HNF-1β ΔC. The number of tubules counted in control cells without HNF-1β ΔC was set as 100%. Error bars indicate SD. * indicates P < 0.05. (C) Examination of levels of STAT3 phosphorylation induced by HGF in the presence or absence of HNF-1β ΔC. (D) Levels of HGF-induced Erk1/2 phosphorylation were decreased in IMCD3 cells expressing HNF-1β ΔC.

Knockdown of SOCS-3 Rescues Defective Tubulogenesis in Cells Expressing Dominant-Negative Mutant HNF-1β.

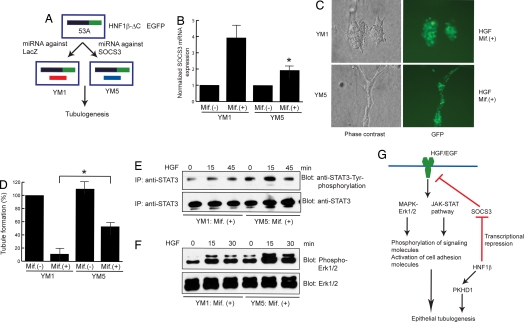

To investigate whether HNF-1β regulated tubulogenesis through SOCS-3, we tested whether knockdown of SOCS-3 would rescue the defect in tubulogenesis in cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. mIMCD3 cells expressing the HNF-1β ΔC mutant were stably transfected with vectors encoding miRNA against either SOCS3 or lacZ as a negative control (Fig. 4A). In the cell line expressing SOCS3 miRNA, the induction of SOCS3 by HNF-1β ΔC was inhibited 55% compared with control cells expressing miRNA against lacZ (Fig. 4B). Knockdown of SOCS3 partially rescued HGF-dependent tubule formation in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β (Fig. 4C). Quantification of these data showed that knockdown of SOCS3 increased tubule formation by 5-fold compared with cells expressing control siRNA (Fig. 4D). Further assessment of cell signaling indicated that knockdown of SOCS3 restored HGF-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 and STAT3 in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative HNF-1β (Fig. 4 E and F).

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of SOCS-3 rescues defective tubulogenesis in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. (A) mIMCD3 cells expressing HNF-1β ΔC were stably transfected with vectors that expressed microRNA against lacZ (control) or SOCS3. (B) Inhibition of SOCS3 mRNA levels in cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β and SOCS3 siRNA as revealed by quantitative PCR. (C) siRNA to lacZ (control) had no effect on defective tubule formation in mIMCD3 cells expressing dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β, indicated by the failure of GFP-positive cells to form tubules. Decreasing the levels of SOCS3 by siRNA rescued HGF-induced tubulogenesis, as indicated by the formation of GFP-positive tubules in 3D collagen gels. (D) Quantification of tubule formation in cells expressing siRNA against lacZ or SOCS3 in the presence of HNF-1β ΔC. The numbers of tubules counted in control cells without HNF-1β ΔC was set as 100%. Error bars indicate SD. * indicates P < 0.05 compared with control cells. (E) Assessment of STAT3 phosphorylation induced by HGF in mIMCD3 cells expressing HNF-1β ΔC in the presence or absence of SOCS3 siRNA. (F) Restoration of Erk1/2 phosphorylation in cells expressing HNF-1β ΔC by knockdown of SOCS3. (G) HNF-1β regulates tubulogenesis by controlling the levels of SOCS-3 expression, which in turn regulates the flow of signaling from HGF to effector molecules involved in tubule formation. In addition, HNF-1β also controls tubulogenesis by regulating transcription of PKHD1.

Discussion

Mutations of HNF-1β produce inherited renal cysts and diabetes (RCAD/MODY5) and are increasingly recognized as a common cause of sporadic renal hypoplasia/dysplasia (CAKUT). To understand the basis for these disorders, we performed a genome-wide analysis of HNF-1β target genes in the kidney. Using an innovative approach combining ChIP-chip with mRNA microarray analysis, we identified SOCS3 as a previously unrecognized HNF-1β target gene. HNF-1β binds to the SOCS3 promoter and represses SOCS3 transcription. The effect on SOCS3 is specific, because other members of the SOCS family are not inhibited. Mutations of HNF-1β, either in HNF-1β knockout mice or renal epithelial cells expressing a dominant-negative mutant, lead to overexpression of SOCS3. Increased levels of SOCS-3 inhibit HGF-dependent tubulogenesis by decreasing the phosphorylation of Erk and STAT-3. These findings reveal a mechanism that explains how mutations of the transcription factor HNF-1β produce CAKUT. Manipulating the aberrant levels of SOCS-3 may be a useful approach for treating the renal malformations caused by mutations of HNF-1β.

HNF-1β regulates renal epithelial tubulogenesis by controlling the levels of SOCS-3, which in turn modulates the intensity and duration of activation by HGF (Fig. 4G). In addition to HGF, SOCS-3 negatively regulates signaling by other growth factors and cytokines, including EGF, insulin-like growth factor-1, leukemia inhibitory factor, fibroblast growth factor, and angiotensin-II (17, 27–29). Many of these factors have also been shown to play critical roles in tubule formation and nephrogenesis (30, 31). Thus, inhibition of SOCS-3 expression by HNF-1β may represent a general mechanism for regulation of epithelial morphogenesis. Moreover, PKD1, which is mutated in humans with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, encodes a protein called polycystin-1 that directly activates JAK/STAT signaling (32). Dysregulation of SOCS-3 may also inhibit polycystin-1 signaling and thereby promote kidney cyst formation in mammals with mutations of HNF-1β. Because mutations of HNF-1β produce developmental anomalies in other epithelial organs whose formation depends on HGF signaling, including the pancreas and liver, dysregulation of SOCS-3 may be importantly involved in congenital abnormalities in these organs as well.

Knockdown of SOCS3 by RNA interference rescues the defect in tubulogenesis caused by expression of dominant-negative mutant HNF-1β. However, cells expressing SOCS3 miRNA exhibit a 50% decrease in tubulogenesis compared with wild-type cells, suggesting that additional genes controlled by HNF-1β are involved in tubule formation. Another HNF-1β target that has been identified in the kidney is Pkhd1, the gene that is mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. We have shown that HNF-1β directly regulates the Pkhd1 promoter, and mutations of HNF-1β inhibit Pkhd1 expression in vivo (6, 7). Mai et al. (33) have shown that knockdown of Pkhd1 disrupts tubulogenesis in cultured IMCD cells. These findings suggest that HNF-1β- dependent expression of Pkhd1 may also play a role in epithelial morphogenesis (Fig. 4G).

The identification of SOCS3 as a gene target of HNF-1β may explain other phenotypic features of MODY5. In contrast to most forms of MODY, in which plasma insulin levels are reduced because of a defect in secretion, patients with MODY5 can present with elevated plasma insulin levels and insulin resistance. SOCS-3 inhibits insulin receptor signaling, and over-expression of SOCS-3 in adipose tissue produces insulin resistance (34). Overexpression of SOCS-3 in the pancreas using a β cell-specific promoter leads to a reduction in β cell mass (35). Mutations of HNF-1β have been suggested to reduce β cell mass in zebrafish and possibly also in mammals (36). Therefore, increased SOCS-3 expression resulting from HNF-1β mutations may also underlie the reduced β cell mass and insulin resistance in MODY5.

Methods

Cell Lines.

mIMCD3 cells and mIMCD3 cells expressing the HNF-1β ΔC mutant were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Mice and Animal Procedures.

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Kidney-specific inactivation of HNF1β was achieved by using Cre-LoxP recombination by crossing KspCre mice with HNF1βflox/flox mice as described (6). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Pasteur Institute.

Antibodies and Reagents.

Antibodies used were rabbit anti-HNF-1β sc-22840 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-SOCS-3 (Abcam); rabbit anti-JAK2 (Upstate Biotechnology); anti-phospho-JAK2 (Biosource); rabbit anti-STAT3, anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr-705), anti-Erk1/2, and anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology); and anti-histone modification antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology). Cellmatrix Type I-A collagen solution was obtained from Wako, and recombinant mouse HGF was from R&D Systems.

siRNA.

mIMCD3 cells were stably transfected with vectors encoding miRNA against either SOCS3 or lacZ using BLOCK-iT Pol II miR RNAi expression vector kits (Invitrogen). Sequences of the siRNA are provided in SI Text.

ChIP-Chip and Quantitative ChIP Assays.

Detailed descriptions of the chromatin immunoprecipitation protocols are provided in SI Text.

Microarray and Quantitative RT-PCR.

Detailed descriptions of the microarray and quantitative RT-PCR are provided in SI Text.

Cloning and Luciferase Reporter Assays.

The mouse SOCS3 promoter was amplified by using long range PCR kits (Roche) and subcloned into pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). The integrity of the promoter sequence was confirmed by sequencing. Cells were transfected with Fugene reagent (Roche), and luciferase activity was measured by using a Wallac VICTOR V multilabel counter (Perkin–Elmer).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis.

Cells were serum-starved for 24 h before treatment with HGF (50 ng/ml). Treated cells were lysed with modified RIPA buffer and subjected to immunoprecipitation as described (37).

In Situ Hybridization.

In situ hybridization was performed by using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes for mouse SOCS3. Detailed protocols are provided in SI Text.

Tubulogenesis in 3D Collagen Gels.

Cells were trypsinized to form a single-cell suspension and mixed with collagen gel solution at a concentration of 100,000 cells/ml. The collagen gels were allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 4 h and media containing 2% FBS was added. Tubule formation was induced by HGF (50 ng/ml) and tubulogenesis was quantified as described (26, 38).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by using Student's t tests with Dunnett's correction for multiple comparisons where applicable. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Drs. Jeffrey S. Flier and Christian Bjorbaek for designing the SOCS3 in situ hybridization probe. We thank Patricia Cobo-Stark, Eric Gourley, and Jeffrey Kirkland for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01DK42921 (to P.I.), Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale Grant FRMDEQ20061107958 (to M.P.), and the University of Texas Southwestern O'Brien Kidney Research Core Center (National Institutes of Health Grant P30DK079328). Z.M. is supported by a Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation fellowship. E.F. is an Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale researcher.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705957104/DC1.

References

- 1.Tronche F, Yaniv M. BioEssays. 1992;14:579–587. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenfeld M, Maury M, Chouard T, Yaniv M, Condamine H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1991;113:589–599. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindner TH, Njolstad PR, Horikawa Y, Bostad L, Bell GI, Sovik O. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Chauveau D, Gautier JF, Dubois-Laforgue D, Clauin S, Beaufils S, Wilhelm JM, Boitard C, Noel LH, Velho G, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:510–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edghill EL, Bingham C, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. J Med Genet. 2006;43:84–90. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gresh L, Fischer E, Reimann A, Tanguy M, Garbay S, Shao X, Hiesberger T, Fiette L, Igarashi P, Yaniv M, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:1657–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiesberger T, Bai Y, Shao X, McNally BT, Sinclair AM, Tian X, Somlo S, Igarashi P. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:814–825. doi: 10.1172/JCI20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiesberger T, Shao X, Gourley E, Reimann A, Pontoglio M, Igarashi P. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10578–10586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf AS, Price KL, Scambler PJ, Winyard PJD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:998–1007. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113778.06598.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knuppel T, Charbit M, Dusek J, Ghiggeri GM, Jankauskiene A, Mir S, Montini G, Peco-Antic A, et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decramer S, Parant O, Beaufils S, Clauin S, Guillou C, Kesler S, Aziza J, Bankin F, Schanstra JP, Bellanne-Chantelot C. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:923–933. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild W, Pogge von Strandmann E, Nastos A, Senkel S, Lingott-Frieg A, Bulman M, Bingham C, Ellard S, Hattersley AT, Ryffel GU. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4695–4700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080010897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haumaitre C, Barbacci E, Jenny M, Ott MO, Gradwohl G, Cereghini S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1490–1495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405776102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, Tronche F, Schutz G, Babinet C, Pontoglio M, Yaniv M, Barra J. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2002;129:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TH, Barrera LO, Zheng M, Qu C, Singer MA, Richmond TA, Wu Y, Green RD, Ren B. Nature. 2005;436:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature03877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott J, Johnston JA. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray PJ. J Immunol. 2007;178:2623–2629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura A, Kinjyo I, Matsumura Y, Mori H, Mashima R, Harada M, Chien KR, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6905–6910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu E, Cote JF, Vuori K. EMBO J. 2003;22:5036–5046. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karihaloo A, Nickel C, Cantley LG. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;100:e40–e45. doi: 10.1159/000084111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosario M, Birchmeier W. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boccaccio C, Ando M, Tamagnone L, Bardelli A, Michieli P, Battistini C, Comoglio PM. Nature. 1998;391:285–288. doi: 10.1038/34657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishibe S, Joly D, Liu ZX, Cantley LG. Mol Cell. 2004;16:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien LE, Tang K, Kats ES, Schutz-Geschwender A, Lipschutz JH, Mostov KE. Dev Cell. 2004;7:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros EJ, Santos OF, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Nigam SK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4412–4416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dey BR, Furlanetto RW, Nissley P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:38–43. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan JC, Rabkin R. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Zvi T, Yayon A, Gertler A, Monsonego-Ornan E. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:380–387. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai H, Barros EJ, Tsukamoto T, Barasch J, Nigam SK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6279–6284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plisov SY, Yoshino K, Dove LF, Higinbotham KG, Rubin JS, Perantoni AO. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:1045–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Boletta A, Liu L, Qian F, Xu PN, Germino FJ, Germino GG. Cell. 2002;109:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mai W, Chen D, Ding T, Kim I, Park S, Cho SY, Chu JS, Liang D, Wang N, Wu D, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4398–4409. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi H, Cave B, Inouye K, Bjorbaek C, Flier JS. Diabetes. 2006;55:699–707. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindberg K, Ronn SG, Tornehave D, Richter H, Hansen JA, Romer J, Jackerott M, Billestrup N. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:231–243. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song J, Kim HJ, Gong Z, Liu NA, Lin S. Dev Biol. 2007;303:561–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Z, Shah RC, Chang MJ, Benveniste EN. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5496–5509. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5496-5509.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wozniak MA, Keely PJ. Biol Proc Online. 2005;7:144–161. doi: 10.1251/bpo112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.