Abstract

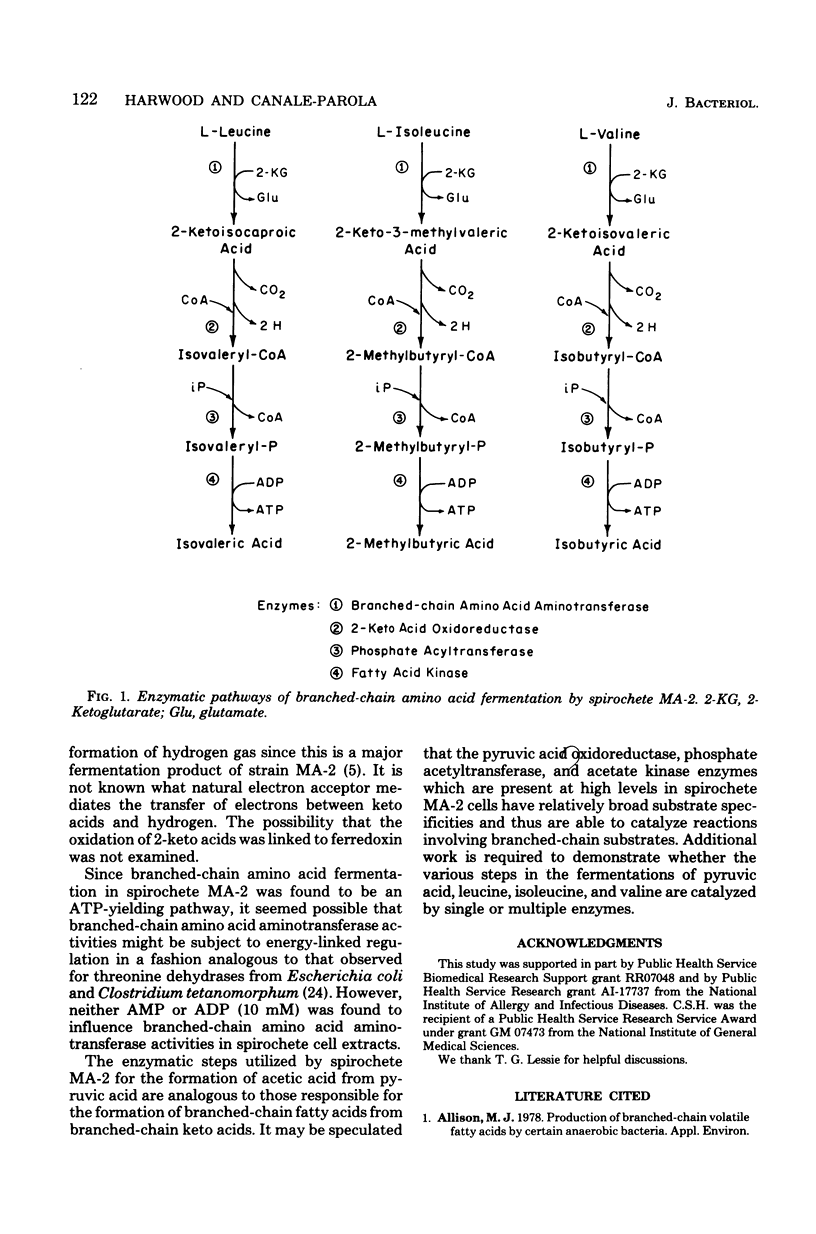

The metabolic pathways utilized by an obligately anaerobic marine spirochete (strain MA-2) to ferment branched-chain amino acids were studied. The spirochete catabolized l-leucine to isovaleric acid, l-isoleucine to 2-methylbutyric acid, and l-valine to isobutyric acid, with accompanying CO2 production in each fermentation. Cell extracts of spirochete MA-2 converted l-leucine, l-isoleucine, and l-valine to 2-ketoisocaproic, 2-keto-3-methylvaleric, and 2-ketoisovaleric acids, respectively, through mediation of 2-ketoglutarate-dependent aminotransferase activities. The branched-chain keto acids were decarboxylated and oxidized to form isovaleryl coenzyme A, 2-methylbutyryl coenzyme A, and isobutyryl coenzyme A, respectively, in the presence of sulfhydryl coenzyme A and benzyl viologen. The acyl coenzyme A's were converted to acyl phosphates by phosphate branched-chain acyltransferase enzymatic activities. Branched-chain fatty acid kinase activities catalyzed formation of isovaleric, 2-methylbutyric, and isobutyric acids from isovaleryl phosphate, 2-methylbutyryl phosphate, and isobutyryl phosphate, respectively. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate was formed during conversion of branched-chain acyl phosphates to branched-chain fatty acids. The results indicate that conversion of l-leucine, l-isoleucine, and l-valine to branched-chain fatty acids by spirochete MA-2 results in adenosine 5′-triphosphate generation. The metabolic pathways utilized for this conversion involve amino acid amino-transferase, 2-keto acid oxidoreductase, phosphate acyltransferase, and fatty acid kinase activities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allison M. J., Bucklin J. A., Robinson I. M. Importance of the isovalerate carboxylation pathway of leucine biosynthesis in the rumen. Appl Microbiol. 1966 Sep;14(5):807–814. doi: 10.1128/am.14.5.807-814.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison M. J., Peel J. L. The biosynthesis of valine from isobutyrate by peptostreptococcus elsdenii and Bacteroides ruminicola. Biochem J. 1971 Feb;121(3):431–437. doi: 10.1042/bj1210431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz J. C., McCallum R. E. Growth yields and fermentation balance of Bacteroides fragilis cultured in glucose-enriched medium. J Bacteriol. 1979 Mar;137(3):1263–1270. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1263-1270.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood C. S., Canale-Parola E. Branched-chain amino acid fermentation by a marine spirochete: strategy for starvation survival. J Bacteriol. 1981 Oct;148(1):109–116. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.1.109-116.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES M. E., BLACK S., FLYNN R. M., LIPMANN F. Acetyl coenzyme a synthesis through pyrophosphoryl split of adenosine triphosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953 Sep-Oct;12(1-2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda T. Fatty acids of the genus Bacillus: an example of branched-chain preference. Bacteriol Rev. 1977 Jun;41(2):391–418. doi: 10.1128/br.41.2.391-418.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore B. P., Johnson R. C. Lipids of the Spirochaetales: comparison of the lipids of several members of the genera Spirochaeta, Treponema, and Leptospira. J Bacteriol. 1974 Dec;120(3):1268–1273. doi: 10.1128/jb.120.3.1268-1273.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysko P. G., Cox C. D. Respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1978 Aug;21(2):462–473. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.462-473.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R. E., Warren L. G., Susskind B., Lo H. S. An energy-conserving pyruvate-to-acetate pathway in Entamoeba histolytica. Pyruvate synthase and a new acetate thiokinase. J Biol Chem. 1977 Jan 25;252(2):726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson I. M., Allison M. J. Isoleucine biosynthesis from 2-methylbutyric acid by anaerobic bacteria from the rumen. J Bacteriol. 1969 Mar;97(3):1220–1226. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.3.1220-1226.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STADTMAN E. R., BARKER H. A. Fatty acid synthesis by enzyme preparations of Clostridium kluyveri. VI. Reactions of acyl phosphates. J Biol Chem. 1950 Jun;184(2):769–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STADTMAN E. R., NOVELLI G. D., LIPMANN F. Coenzyme A function in and acetyl transfer by the phosphotransacetylase system. J Biol Chem. 1951 Jul;191(1):365–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STADTMAN E. R. The coenzyme A transphorase system in Clostridium kluyveri. J Biol Chem. 1953 Jul;203(1):501–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda K., Rabinowitz J. C. Pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase. 3. Purification and properties of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1971 May 25;246(10):3111–3119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwinkel E., Furmanski P., Reeves H. C., Ajl S. J. Growth of Escherichia coli on fatty acids: requirement for coenzyme A transferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1968 Dec 30;33(6):902–908. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(68)90397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H. C., Lessie T. G. Branched chain amino acid aminotransferase isoenzymes of Pseudomonas cepacia. Arch Microbiol. 1979 Mar 12;120(3):223–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00423069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]